Abstract

This chapter explores management from the perspective of a fishing community located in the Pearl Lagoon basin of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. The chapter seeks to address the following questions: How do fishing households in the Pearl Lagoon area respond to management plans designed by regional agencies and national authorities? How is poverty understood and experienced by fishing families and individuals? How is access to land – meaning securing land and aquatic rights – affecting the livelihoods of the people living in fishing communities of the area? Which coping strategies have people undertaken to reduce the vulnerability of their livelihoods?

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

We depend on the fish, even if the price went down. We cannot buy a pound of rice with a pound of fish, but we have to keep fishing, because there is no other source to have an income, to make a life. And the agricultural production you cannot sell. So you have to just do it. There is no other alternative. Even if this fish is 8 Córdobas (50 cents US) per pound, you have to sell it. What can you do?

Leroy Bennett, fisherman

Tasba (paunie) gave us authorization to grant fishing permissions over our territorial waters. Our community has laws, but there is no enforcement to support us. We need the government to help us enforce this law.

Asolin Chang, fisherman and president of the fishing cooperative, Marshall Point

The study focused the research in Marshall Point – a coastal fishing community of indigenous/Afro-descendant origins – located on the west margins of the Pearl Lagoon basin. The research found that Marshall Point seems to be confronting critical dilemmas related to the sustainability of its vital natural resources – land and water. Historical accounts indicate that the community has struggled to secure land and aquatic rights from its surrounding communities (Tasbapaunie and Pearl Lagoon communities), as well as from the Nicaraguan state. These efforts have been made in the context of ever-increasing exploitation of the resources of the Pearl Lagoon basin, particularly fish. At the community level, the research revealed an incipient process of socioeconomic differentiation among individuals and families, which originates from competing dynamics among community members in the light of declining resources. In addition, conflicts over resource use (for instance, cattle-ranching versus small-scale agricultural activities and the use of unsustainable fishing gears) have begun to challenge deep-seated concepts, practices, and norms concerning the sustainable use of natural resources.

Faced with these predicaments such as undefined property rights, internal conflicts over resource use, the exhaustion of the fishing stocks, and the continuous marginalization from spaces in which relevant policies originate (i.e., the design of management plans, and the land titling process), fishermen from Marshall Point have developed a variety of mechanisms to cope with vulnerability and mounting poverty. These mechanisms include, though are not limited to: (1) strategizing toward securing land and aquatic rights; (2) shifting labor from fishing to agricultural production with the aim of securing food supplies and basic dietary needs; (3) organizing a fishing cooperative aimed at timely access of national funding for fisheries development; and, (4) implementing informal community-based actions inspired by sustainable principles to manage the resources of the Lagoon.

However, as the chapter demonstrates, in order for these mechanisms to be effective in the long run, they require sound governance in the area – which includes (though is not limited to) a proactive central state; as well as purposeful local (communal and municipal) and regional authorities. Internally, strategies to overcome poverty, upon which some families have embarked (e.g., overfishing, cattle-raising) run the risk of further marginalizing and impoverishing vulnerable groups (elders and women) in the community.

This study examines the rationale through which community members have responded to policy initiatives aimed at implementing management systems in the Pearl Lagoon basin. In doing so, the research associates policies toward management systems of the resources of the Lagoon to ongoing processes of land surveys intended to grant communal land to indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples. Community members’ attitudes and rationale toward management are placed in a broader scope, with the purpose of comprehending livelihood strategies and the community efforts in confronting historical socioeconomic changes, vulnerability, and marginalization. The chapter delves into the tenets that underlined management designs during the 1990s as promoted by competing policy actors in the area; and seeks to comprehend whether such schemes were able to incorporate the needs and aspirations of the people from Marshall Point. In understanding the perspectives of the community, we draw from local perceptions of poverty, on the assessment that community members formulate with regard to their natural environment and resource base, and their strategies toward empowerment.

At the theoretical level, we hypothesize that management is better understood within the concepts of social power and the livelihood approach (Mukherjee Reed 2008, pp. 26–27). As we hope to demonstrate throughout this chapter, management has limited possibilities for success when the agency for sustainable development is affected solely by outside actors (both governmental and non-governmental), within a precarious governance framework; and through partial participation by the owners of the resources. The chapter argues that the potential of management in promoting sustainable fisheries in the Pearl Lagoon has been further restricted due to the narrow understanding of poverty that has transpired, affecting policy initiatives in the area over the last two decades.

A case in point has been the lack of integration of land and aquatic rights within management schemes. Both land claims and aquatic rights have had an historical significance in Marshall Point’s struggle against political marginalization and poverty. Having continuous access to land and aquatic resources might explain the community resilience in the light of socioeconomic and ecological transformations. It can also be argued that this question is also significant for other communities in the area (Nietschmann 1973; Hale 1994). Hence, we suggest that the need to preserve a sustainable resource base has forced Marshall Point people to develop a multi-faceted approach to cope with the further impoverishment of their livelihoods.

The chapter identifies four decisive actions in which individuals, families, and community institutions have engaged in their efforts to overcome poverty, vulnerability, and marginalization: (1) strategizing toward securing land and aquatic property rights ; (2) shifting labor from fishing to agricultural production with the aim of securing food supplies in times of economic vulnerability and fluctuating market prices for fish and shrimps; (3) organizing a fishing cooperative aimed at accessing national funding for fisheries development; also, a process toward reinvigorating community governing bodies is also noticeable. Finally, (4) implementing informal community-based actions to manage the resources of the Lagoon. This last effort has emerged as a creative innovation between management plans designed by outside actors, and local/communal imperatives for protecting the resources of the Lagoon.

At a more general level, the chapter attempts to scrutinize the relationship between environmental insecurity and poverty. We contend that the effect that environmental insecurity and degradation have on poverty (and vice versa) should be understood within a rights-based approach. For instance, in some particular contexts – such as the case study we are discussing here – securing individual access and collective rights over land and aquatic resources might be seen as necessary conditions for fisher communities to cope with, and eventually overcome, poverty. This question calls upon the design of management systems sensitive enough to take into account the voices of the owners of the resources, the role of their collective governing institutions in decision-making processes, and the livelihood strategies households have unfolded to confront poverty and marginalization.

Management systems unable to capture the multi-dimensional features through which a fisher community understands, copes with, and experiences poverty and marginalization would be certainly limited, based on their lack of capacity, to address the needs of providing a sustainable resource base (Berkes et al. 2000). By the same token, empowerment should be analyzed as the capacity of the community to mobilize the resources at their disposal toward social and economic transformation. Thus, empowerment is for fisher communities an enabling process through which poverty can be tackled. The notion of social power captures the agency “from below,” through which we try to explain Marshall Point’s strategizing in coping with poverty.

The chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 is dedicated to the theoretical framework in which we highlight the theoretical literature as the basis for discussing artisanal fisheries, poverty, and empowerment. The livelihood approach, we propose, better captures the local dynamics in which individuals, families, and the community confront environmental insecurity, resource degradation, and marginalization. We suggest that the livelihood approach should be supplemented with a rights-based understanding of how local community members cope with social and institutional constraints. Therefore, opportunities for local organizing and agency are conceived as devices of social power that explains community-based mechanisms and actions to fight poverty. In Sect. 3 we describe the research methods. Section 4 provides background information on the Pearl Lagoon basin, its natural and sociocultural environment. Overexploitation of natural resources, population increase, and the precarious governance setting are highlighted in this section. Section 5 discusses property rights and commercial fishing in the study area. Section 6 describes and assesses the management initiatives in the Lagoon, as proposed by development actors. This section also examines how residents of Marshall Point cope with poverty and disempowerment. Finally, Sect. 7 offers the research findings.

2 Theoretical Framework

The literature on poverty is extensive. That being the case, we found it important to discern a working definition able to guide our research. Income-based and “basic-needs” approaches to poverty have been considered insufficient to capture the dynamics of artisan fisheries. For instance, although a “basic needs” approach might help us to determine absolute and relative poverty, it might not help us to assess the way in which it is conceived, experienced, and acted upon by local people. Such approaches may also be limited in grasping historical transformations a social group has experienced with regard to its understanding of poverty, or to assess the rationale of its adaptive strategies. Therefore, we decided to utilize a notion of poverty receptive to material needs (such as income), but supplemented with a multi-dimensional focus (for instance, social exclusion and discrimination). This conceptual integration allowed comprehending a community’s adaptive strategies for coping with the instability of food supply, for example, due to the volatile market prices for fish and shrimps; or as a result of the overexploitation of the Pearl Lagoon resources. Stressing the multi-dimensional character of poverty also provides a better exploration of social manifestations of poverty and power relationships, which play a critical role in understanding marginalization. Furthermore, social exclusion and ethnic discrimination may explain the ambivalence through which Marshall Point’s communal authorities have handled claims toward land and aquatic rights, historically.

2.1 Livelihoods and Small-Scale Fisheries

We studied Marshall Point’s socioeconomic transformation and current challenges in confronting poverty from the perspective of the sustainable livelihoods approach (Allison and Ellis 2001). As pointed out in the literature, fisher households confront crucial imperatives in their pursuit for an increased well-being. The capacity to do so is dependent on their access to various sorts of capital assets, which may be natural, physical, human, financial, or social. Access in turn, is conditioned upon social and institutional factors, which may constrain or provide opportunities for livelihoods strategies to unfold.

In coming to terms with the literature on sustainable livelihoods, we reflected upon the need to relate access (to capital assets) and capabilities (for mobilizing adaptive strategies and/or coping mechanisms) with empowerment. In doing so, access and capabilities were conceptualized within a social power perspective (see diagram below). Based on Friedmann (1992), we grasp the interplay of various types of social power, as they are integrated within artisanal fisheries. Friedmann identifies eight bases of social power: (1) defensible life space; (2) surplus time; (3) knowledge and skills; (4) appropriate information; (5) social organization; (6) social networks; (7) instruments of work and livelihood; and (8) financial resources (Friedmann 1992, p. 69). Empowerment, in Friedmann’s view, may occur as the result of an increased access to single elements of these bases. Rather than assuming that these elements are “structurally” interconnected in the life of social groups, we propose to test their actual interactions as they materialize in livelihood strategies as processes of agency and empowerment (Jentoft 2005). This is, to be attentive to “the processes through which social and political powers are acquired,” and to conceptualize human development as “the processes of mobilizing social and/or political power to affect social relationships of structural inequality” (Mukherjee Reed 2008, p. 28).

Mukherjee-Reed also proposes to focus attention on four dimensions through which social relationships might be altered: (1) “the division of labor and the processes of material reproduction/production; (2) decision-making processes; (3) the realm of norms/culture/values; and finally, (4) the ownership of knowledge production” (2008, p. 28). For the purpose of this study, we find it relevant to explore the extent to which these dimensions of social relationships have changed over time, through the history of the community. We would argue that various degrees of changes in these realms inform the variety of mechanisms that Marshall Point has turned to in order to cope with poverty and vulnerability.Footnote 1

In synthesis, we propose studying agency and empowerment “from below,” without disregarding the effects development initiatives “from above” may have in generating sociopolitical changes conducive to empowerment and minimizing vulnerability (Fig. 13.1).

Empowerment from below and human development. Poverty is multidimensional (a), communities have access to material and immaterial capital assets, which create conditions and possibilities for empowerment (b, c). In turn, they often result in multifaceted strategies which can be analyzed from a social power approach (d)

3 Research Methods

With regard to methods, the study included two phases. First, a literature review on the topic of small-scale fisheries and poverty was conducted, looking at current debates in the field. In addition, we delved into studies developed in the Pearl Lagoon basin. We focused our pursuit on research related to fisheries, recent development initiatives, and available reports on population increase in the study area. While up-to-date official (government-based) sources were limited, we found a significant amount of information (published and unpublished) generated by two major development/research initiatives in the Pearl Lagoon region, implemented during the 1990s: The Proyecto para el Desarrollo Integral de la Pesca Artesanal de la Región Autónoma Atlántico Sur (Project for the Integral Development of Artisanal Fisheries in the South Atlantic Autonomous Region, (DIPAL, for its Spanish acronym)) and the Coastal Area Monitoring Project and Laboratory (CAMPLab), both discussed later in the chapter. Substantive secondary information both from DIPAL and CAMPLab have been incorporated into the present chapter, particularly with regard to the design of management systems.

The second phase of the study consisted of field research. This was conducted in two parts – a 2-week period during the dry season (February 2009); and a 1-month period in the rainy season (July/August 2009). Field research during both periods consisted of ethnographic research, mostly through observations, participant observations, interviews, focus groups, and field trips to fishing and agricultural areas in Marshall Point and its surroundings.Footnote 2 Two open-ended questionnaires for interviews were designed. The first one, utilized during the first research period, aimed at understanding historical transformations on the use of natural resources, socioeconomic activities, and sociocultural aspects of the community.

This questionnaire was used in interviews with elders – male and female – and adult fishermen. The second questionnaire, used during the second visit, was designed to capture locally held notions of land and aquatic rights and poverty; as well as to inquire into the livelihood strategies families and individuals have adopted in order to cope with poverty and marginalization. This second questionnaire was mostly used in interviews with adults, young adults and community members who held positions of authority in local governing bodies and community institutions.

While ethnographic techniques provided valuable qualitative information, our study also included quantitative data, gathered through both a community census (conducted twice, for the purpose of reliability), and a socioeconomic survey. The survey, aimed at obtaining data from fishing and agriculture as well as income-generation activities, was conducted with 95% of the community households. The gathered data (both qualitative and quantitative) also benefited from the collaborative research approach our study framed from the onset.

Through a series of community assemblies, as well as meetings with fishermen collectives, our research project’s objectives received significant insights.Footnote 3 At the same time, the study envisioned research data that can potentially be used for the purpose of contributing to the organizing process of the community’s fishermen who at that time were seeking financial support from the Nicaraguan Institute for Fisheries (Instituto Nicaragüense de la Pesca (INPESCA)).Footnote 4

4 Nicaragua and Its Caribbean Coast – A Brief Historical Note

Nicaragua is the second poorest country in Latin America. According to the World Bank, the incidence of poverty is 46.2%, while the population living in conditions of extreme poverty is 14.9%.Footnote 5 Economic recovery since the end of the Contra War during the 1980s has been troublesome.Footnote 6 Although poverty levels have been reduced in the last decade, and the country has made significant progress toward improving its overall economic performance, human development gaps, social inequality, and unemployment remain high.

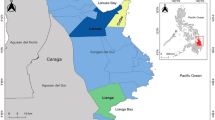

Development gaps are particularly acute in the Nicaraguan Caribbean Coast regions (from here on referred to as “the Coast”), which comprise approximately half of the Nicaraguan territory, and where 12% of the national population lives. UNDP data from 2005 estimated the human development index (HDI) to be 0.466 and 0.454 for the Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (North Atlantic Autonomous Region, (RAAN)); and the Región Autónoma del Atlántico Sur (South Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAS)), respectively (PNUD 2005, p. xxi; Fig. 13.2). These indexes are comparable to current data reported on Gambia (0.471) and Zambia (0.453), in West Africa. Nicaragua as a country ranks position 124 (0.699) on the HDI scale for 2009 out of 182 countries with data.Footnote 7 However, the Pearl Lagoon basin has a relatively higher human development index (0.622) in comparison to other municipalities in the RAAS (PNUD 2005, p. 68). This might be explained by improvements in access to social services (particularly health and education) in the area over the last decade.

Historical relationships between the Coast society and the Nicaraguan state have been characterized by contention and mutual distrust. Pacific Nicaragua was originally colonized by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, while the Coast had the early arrival of English colonizers almost a century after (around the 1600s). During the nineteenth century, the British established a Protectorate, promoted trade with local indigenous peoples, and later in 1860, instituted an indigenous/Creole self-governing entity (the Moskito Reserve). The Reserve lasted until 1894 when it was dismantled by the Nicaraguan state, which got hold of formal sovereignty in the Coast region. Disputes for sovereignty revolved around the Coast’s natural resources. The British presence was substituted by the United States, who instituted an enclave economy in connivance with Nicaraguan governments. The region’s forests and mines – gold and silver – were intensively exploited. During the twentieth century, the Somoza regime (1934–1979) continued this trend of seeing and acting upon the Caribbean Coast as a reservoir of natural resources, one that must be exploited for the benefit of outside economic agents. The Nicaraguan state has therefore instigated historical animosity and mistrust on the part of the Coast society.

In 1979, an armed revolutionary movement, the Sandinista Front of National Liberation (FSLN), overthrew the Somoza regime. One of the FSLN government’s first policy initiatives was to nationalize the country’s natural resources. However, this and other policy decisions prompted frictions with the Coast population who had perceived Nicaraguan governments with suspicion, in particular on issues related to the use of the region’s natural resources. Land claims, access and control over natural resources, and political participation were crucial demands brought to the fore by culturally diverse indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples and their organizations in the context of a national democratic opening.

In the context of external hostilities against the Sandinista government by the US administration, tensions along the Coast with indigenous and Afro-descendent organizations evolved from political conflict toward an open-armed confrontation. The conflict, which lasted for about 6 years (from 1981 till 1987), was extremely divisive, caused displacement of large segments of the regional population, and many people died. In 1987, and after various rounds of negotiations and consultations, the Sandinista government granted regional autonomy to the Costeño people. Specific cultural, economic, and political rights were recognized for the inhabitants of the Coast, and self-governing regulations were instituted on matters related to the protection of communal lands (which cannot be sold or levied), the use and control of natural resources, and political representation.

Autonomy, for the Coast society, is considered a political platform of self-governing rights. In 1990, under the egis of the autonomous regime, two regional multi-ethnic governments were inaugurated, and indigenous, Afro-descendants, as well as Mestizo peoples achieved political representation. However, after almost 20 years, autonomous rights still remain to be materialized. The performance of regional governing institutions has been feeble while their actual influence over regional decision-making is limited. Recognition of communal land has advanced at a low pace; eastward migration of Mestizo colonizers has altered the ethnic composition of the autonomous regions – with consequences in terms of political representation. Furthermore, effective control over natural resources is still an unresolved issue for indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples (Gonzalez 2008).

In synthesis, autonomy represents a decisive legal framework for the Coast population. It has aimed at healing centuries of mutual distrust between two societies, the Caribbean and the Pacific. Nonetheless, levels of poverty and development gaps along the Coast remain significant, and there is little that can be achieved by regional authorities with regard to increasing the well-being of the population in the absence of a collaborative state. In this context, Pearl Lagoon communities have endeavored to assert their collective rights in managing and protecting the resources of the Lagoon in the light of critical internal (e.g., securing food supply and basic sustenance), and external imperatives (e.g., market forces, population increase). Indeed, it is crucial to consider this backdrop from communities’ current strategies in coping with and overcoming poverty and marginalization.

4.1 Pearl Lagoon Basin – Population, History, and Natural Environment

The Pearl Lagoon Basin constitutes an area of great natural and sociocultural diversity. Various studies have characterized the basin’s natural environments as formed by wetlands, pine savannas, mangrove, and tropical rainforests (Christie et al. 2000, pp. 26–32). The Pearl Lagoon itself covers an area of approximately 625 km2, and is formed by an interconnected system of brackish lagoons and rivers, with at least two passages to the open Caribbean ocean to the North and the South (Sánchez 2001, p. 7). Studies have pointed out that this system allows a complex influx of salted and freshwaters, ideal for the reproduction of various species of fish, shrimps, and crabs (Sánchez 2001). According to Christie, 46 species of fish have been identified in the Lagoon (Christie et al. 2000, p. 32).Footnote 8 The relative abundance and distribution of these species varies according to season, salinity, and the levels of oxygen dissolved in the waters (Pérez and van Eijs 2002, p. 21).Footnote 9 In addition, the rich biodiversity that characterizes the natural environment surrounding the Lagoon is the source of animal and vegetal species, highly used by the local population (Fig. 13.2).

The inhabitants of the Pearl Lagoon basin are also culturally and ethnically diverse. English-speaking Creoles and Garifuna peoples constitute two Afro-descendant communities who reside in communities of different sizes around the Lagoon. In addition, Miskitu and Ulwa, both indigenous peoples, have also occupied for time immemorial various scattered communities in the surroundings of the Pearl Lagoon and the Rio Grande delta. Creole and Miskitu communities comprise around 50% of the total population in the basin.Footnote 10 In recent decades, Spanish-speaking Mestizo peasants have migrated from the Pacific part of Nicaragua and new settlements have been founded, mostly up rivers, not in the margins of the Lagoon.Footnote 11 Some studies attribute the main cause of the population increase in the area as resulting from the eastward migration from interior Nicaragua. The inter-census data reports a 40% population increase in a decade (1995–2005) in the Pearl Lagoon basin. However, the natural growth of local indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples should not be underestimated.Footnote 12 Increase in population has also resulted in pressure over the natural resources of the Lagoon, as reported by various studies (Table 13.1).

4.2 Why Study Marshall Point?

There were important considerations in choosing Marshall Point as a research area. First, the population size: 361 inhabitants; 54 houses concentrated in a relatively small coastal settlement allowed us to pursue more engaging ethnographic research techniques with the various segments of the local population (Fig. 13.3).Footnote 13 Second, the scant research that is currently available for the community, and the reasons that might explain this situation, highlighted the need for scholarship on the area. While significant research efforts – both historic and contemporary – have been conducted in Tasbapaunie and Orinoco, the two neighboring communities, Marshall Point has received just marginal attention.Footnote 14 In part, this might be explained by the intermediate sociocultural (also spatial/geographical) position of Marshall Point, which found itself between two poles of assertive and contrasting ethnicities in the Pearl Lagoon, the Miskitu (Tasbapaunie) and the Garifuna (Orinoco).

It is noticeable that, in both communities, a great deal of scholarly attention has focused on processes of socioeconomic transformation due to market forces, ethnic relationships, and cultural change. Although Marshall Point has been described as a Garifuna community, current inhabitants prefer to emphasize the mixed character of their socio-ethnic origins: Garifuna, Miskitu, Kukra, and Creole.Footnote 15 In the past, labeling the community by outside agents as belonging to one of the regionally identified ethnic groups has often meant political and social discrimination.Footnote 16 Our research also sought to investigate the specific role identity has played within community strategies in the direction of securing land and aquatic rights.

Marshall Point’s community authorities also demonstrated early interest in the study, at the first round of consultations. The research coincided with the organizing process – certainly not the first one – to form a community-based fishing cooperative. Therefore, the study presented potential collaboration of mutual interest with the fishermen. Overall, studying Marshall Point’s fishery gave us an opportunity to advance knowledge about the community; but also to engage in a collaborative research methodology suitable for the scope of the present study.

5 Early Ambivalence on Property Rights and the Impact of Commercial Fishing

Marshall Point was populated in the second half of the nineteenth century, probably around the 1870s.Footnote 17 In this sense, it is one of the newest settlements to be populated in the Pearl Lagoon basin. Original inhabitants of Marshall Point arrived from Brown Bank and Kukra Hill. They were from mixed ethnic origins, blacks (or Creoles), Miskitu, and possibly remnants of Kukra Indians, now extinct.Footnote 18 Later on, Garifunas – from La Fe and San Vicente, two surrounding communities, joined them.Footnote 19

Marshall Point had been a small agricultural plantation previously occupied by a US citizen (“Mr. Marshall, a white man”), and it was abandoned when the new settlers arrived into the area.Footnote 20 A common practice of the Moskito Reserve’s authorities was to grant land plots to foreigners (to individual entrepreneurs and firms) with the purpose of forest extraction and commercial agriculture.Footnote 21 The new inhabitants of Marshall Point did not have to request “permission” from the Reserve’s authorities to settle in the former plantation since they “were people from the Atlantic Coast.”Footnote 22

At an unspecified date during the 1930s (probably 1932), Marshall Point inhabitants were invited by public authorities to the town of Pearl Lagoon – which once served as the headquarters of the Reserve – to join a newly emerging administrative municipal jurisdiction. However, representatives of Marshall Point were rapidly dismissed by Pearl Lagoon political authorities arguing that residents of Marshall Point were “karob people,” and therefore they were no longer welcomed “in our community.”Footnote 23 Historical narratives reported that Orinoco – which has been a mostly Garifuna settlement founded in the early to mid-ninetieth century – have also made references to this momentous episode (Figueroa 1999, p. 39).

The incident has been incorporated in local narratives to demonstrate an open discrimination experienced by the community due to an externally imposed ethnic identity. It also provides historical justification for explaining why the community turned to Tasbapaunie – a larger and older Miskitu-inhabited neighboring community – seeking guarantees for their continuous access to land, natural resources, as well as for securing political inclusion within the new governing framework which was in the making. As stated by Uncle Pi, an 86-year-old, respected elder in the community:

We join to get power from them, to control the land, the beach, all the timber, all the log, because you understand, Kurinwas is a big river and the Kurinwas River they say gone to Matagalpa.Footnote 24

The act of inclusion on the part of Tasbapounie’s authorities has been also conceptualized in the community’s social memory as recognition of the Indian ancestry and social identity of Marshall Point’s inhabitants.Footnote 25 Marshall Point’s bonds with Tasbapounie have further been fortified by a sense of common struggle for land rights. Indeed, as a result of these struggles, several land title deeds were secured early in the twentieth century.Footnote 26 Up to the present, Marshall Point has remained as a “sister community,” included in the Tasbapaunie’s communal land claim (CCARC 1998, p. 336).

5.1 The Impact of Commercial Fishing

Commercial fishing along the Caribbean Coast began around the 1950s, and became intensified during the late 1960s and 1970s (Kindblad 2001). Nietschmann (1973) provides a comprehensive account of the impact of commercial fishing of lobster and turtle on Tasbapaunie’s moral economy. Christie and collaborators report that: “Until about the 1960s, Pearl Lagoon fishers usually used hooks-and-lines and harpoons to strike fish in the shallows; a practice that was only effective when fish stocks were abundant” (Christie et al. 2000, p. 39).

The abundance of fish and shrimps before the introduction of commercial fishing was also reported to us by adults and elder fishers of Marshall Point. They also commented upon the earlier capacity for economic self-sufficiency the community had on some of the basic products that form the daily dietary needs. “We never used to buy rice because we had the land and the farmers to cultivate it.”Footnote 27

This was also the case for other agricultural products such as cassava, bananas, pineapple, and dasheen.Footnote 28 It was also reported that the community had once the capacity for producing modest surplus of agricultural products, particularly rice, which could be traded with the surrounding communities. This capacity is now gone, rice is rarely cultivated, and it has to be purchased in Bluefields or the town of Pearl Lagoon.

It also seems that commercial fishing had also triggered a shift in the sexual division of labor. As Ms. Adleen puts it:

In first time men hardly fishing, they do more farming, cut the ground and plant it, and then the women do more fishing, they catch fish and shrimps.Footnote 29

New fishing gears and techniques were introduced by commercial fishing – such as gill nets – and men were dragged out from agriculture toward the cash economy encouraged by the newly established private processing centers. This shift has also been reported by studies conducted in other communities of the Pearl Lagoon basin (Christie et al. 2000).

The introduction of new fishing techniques, in particularly multi-filament gill nets, in turn impacted severely in the fishing stock, which were now placed under a greater catching effort.Footnote 30 Christie notes that, “although gill nets seem to have been introduced in the 1960s, they remained relatively scarce until the late 1980s when government and free-funded development programs supplied them to fishers” (Christie et al. 2000, p. 39). Most community members consider the introduction of gill nets as a critical turning point in the capacity of the Lagoon in providing a stable resource base for food, and a defining moment that brought about both the loss of self-sustainable agriculture and internal socioeconomic differentiation. Local traditional norms have prescribed that hook-lines are to be used in the dry season, while gill nets should be used during the wet/rainy season, when more fish are available. Nonetheless, a common complaint in Marshall Point today is that “people are now fishing with gill net the whole year around,”Footnote 31 which negatively impacts on the sustainability of the lagoon’s resources.

Commercial fishing generated several incentives over local subsistence economies toward cash-based market relationships. Food supplies were now made available in local markets, and therefore a significant effort – in terms of labor – was directed toward fishing, so as to get “cash for the day.” Uncle Pi noted:

When fishing was good, we could buy lots of food. Now that the fishing has gone down low is hard, is better if we did plant rice for the whole year to eat, so you don’t have to buy. But now the rice price is higher, because when rice comes from the US it costs more.Footnote 32

5.2 The Expansion of the Agricultural Frontier

Several authors have noticed a trend along the Coast, described in terms of the expansion of the “agricultural” frontier. Although this is not a new process, it might have been intensified over the last two decades. At the end of the war, development “poles” along the Coast were promoted by national governments, and the expansion of cattle-raising – due to an increased demand for beef – generated an eastward migration of mostly poor peasant colonizers. Indeed, the Coast population grew 4.9% between the 1995 and the 2005 censuses. This rate of growth constitutes a record for all the municipalities of the country. The Pearl Lagoon basin has experienced the impact of this population increase (Table 13.1). New settlements have been established “up rivers” in Wawashang and Patchi Rivers, and land use experienced important transformations (e.g., from forest use to agricultural and cattle-raising production).

This expansion has also instigated tensions between indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, and Mestizo peasants with regard to land tenure. Two concepts of land property have often conflicted: on the one hand, community-held land; and on the other, privately held land as upheld by Mestizo peasants. This tension is even more problematic in a context in which communal lands are yet to be surveyed and demarcated, and therefore competing claims emerge over land property rights between campesinos and indigenous/Afro-descendant peoples.Footnote 33

Until recently, Marshall Point had not faced this tension in a critical manner, which seemed to be the exception in the Pearl Lagoon basin. Though, this has changed. Due to the fact that its land claim has been made in conjunction with Tasbapaunie’s land claim, negotiations with illegal Mestizo occupants is now a matter of common concern of both communal authorities. Indeed, they agreed to form a unified territorial government to oversee their land and to advocate demarcation.Footnote 34

5.3 Socioeconomic Changes and Outward Migration

At the end of the war (around 1986), Marshall Point began to be once more re-inhabited. The armed conflict had provoked displacement with a number of families fleeing the country, and others moving to Bluefields, or “up river” (to Wawashang) seeking refuge. We have estimated that approximately 60% of the population left the community around 1983; and the following year when the armed conflict intensified in the area. Several of these families did not return to the community but others did. Returning to the community meant the possibility for reconciliation but also for economic recovery. However, in 1988, hurricane Joan devastated the area, which made things difficult for returning families to cope with the post-war period (Envío 1989). Fishing represented a potential resource – and perhaps the only one – which communities could rely on. Christie reports that “fish harvest decreased in the 1980s allowing fish stocks to grow, but now have risen again to prewar levels” (Christie et al. 2000, p. 38).

In 1990, the FSLN lost the general elections to a right-wing coalition, which made matters more problematic for the actual implementation of the autonomous regime. The new national government sought to develop a market-based, export-oriented extractive economy. The imperatives and stimuli this shift in policy brought about, induced significant changes along the Coast, and particularly for the Pearl Lagoon economy. New seafood processing plants entered into the area, and a new cycle of market-based, cash economy began. From 1994 until 2007, market for fish, lobster, and shrimps did provide a relatively stable source of cash income for fishermen in the Pearl Lagoon basin. It also provided a source of food supply for their families. This came at the expense of the sustainability of the resource base, and continued the long-term trend of undermining the subsistence agriculture.

Historically, the Coast’s contribution to national seafood supply has been significant. It contributed 35% of national fish production between 1994 and 2007. More concretely, between 1994 and 2007, artisanal fisheries along the Coast contributed 12% of shrimps and 51% of lobster (Panulirus argus) to national volumes (Table 13.2). Seafood products originating in Pearl Lagoon accounted for 6.9% and 4.5% of national volumes in 1998 and 1999, respectively (Hostetler 2005). These levels of extraction might be arriving at their limits.

Over the last 2 years, the effects of overfishing over communities’ well-being have been felt more intensely. This has raised concerns between communities in the Pearl Lagoon areas as well as within communities. In addition, over the last 2 years, international market prices for shrimp, fish, and lobster have declined as the result of contractions in demand, particularly in the US market, where most of Nicaraguan seafood exports are directed.Footnote 35 Processing plants that entered the area early in the 1990s have either shut down or reduced operations, or have moved to Bluefields to minimize operational costs. Itinerant buyers are now sporadic and fish prices are significantly low as compared to previous years. Seeking economic alternatives, individuals and families have started to search for stable jobs outside the community.

Although outward migration is not new, a new wave can be traced over the last 5 years. Our survey estimated that around 10–15% of Marshall Point’s active labor force – youth and adults between 18 and 35 – are now working abroad on international cruise ships or have found seasonal employment in the English-speaking Caribbean. The survey also registered an increase in outward migration the last 5–6 years. Access to remittances from abroad has supplemented the income of a few families in Marshall Point, and to some extent this is contributing to increasing levels of social differentiation internally.

5.4 Increase in Social Differentiation and Changes in Social Organization

Traditional, self-governing authority in the community has relied on two local entities: the communal board and the sorority group (also called “the society”). While the “society” provides material and moral support to community members in times of illness or death, the communal board oversees decision-making with regard to the community life, including matters related to the use, exploitation, and access to natural resources.Footnote 36 The regular functioning of both entities was interrupted during the war, but nowadays they perform an essential role in community life. Churches also exert influence in local matters, though this is done through the direct participation of religious leaders in communal governing bodies, such as the community board.Footnote 37

Internal socioeconomic differentiation does not seem to have been a factor of internal disputes or tensions two decades ago, during the pre-war years. A relatively equitable sexual distribution of labor within households, self-reliance in subsistence agriculture (including some levels of surplus exchange with neighboring communities), and stable access to fish and shrimps from the Lagoon, did not propel internal differentiation in the degree of individual or family’s access to capital assets. Apart for commercial fishing, there was no other market mechanism that produced substantive change in local economic dynamics.Footnote 38

This has now changed drastically. Cattle-raising, which has historically been marginal in Marshall Point is now being promoted by a handful of relatively better-off families. The expansion of pasture fields (potreros) is competing with areas traditionally used for agricultural production. In addition, several fences have been erected which contradict the norms set forth on communally held land traditionally upheld by Marshall Point’s inhabitants. This emerging process of competition over communal land is more critical in context in which land claims are yet to be adjudicated (or demarcated), and when the community is also confronting encroachment by external occupants (also competing with agricultural areas), including from its neighboring community, Orinoco.

In synthesis, over the last decade, the Caribbean Coast has experienced important socioeconomic and political changes. Some of these may be explained by internal factors and long-term trends and dynamics – such as the contrasting development gaps between Pacific Nicaragua and the Coast. Others are related to external processes – such as the fluctuating market prices for sea products – which are better comprehended by looking at the changing patterns in the global political economy. Both processes – internal and external socioeconomic and political factors – have represented constraints and opportunities for the subsistence economy and social organization of the Pearl Lagoon basin.

The long-term trend of overexploiting the resources of the Lagoon is probably reaching its limits in terms of guaranteeing a secure resource base for future generations. For Marshall Point, as well as for other communities in the area, this represents a critical challenge for coping and eventually overcoming poverty and marginalization; considering the slow pace through which communal land recognition has advanced. Though, livelihood adaptive strategies (for instance, outward migration or shifting toward agriculture in times of crisis) are exhibiting a certain capacity for community resilience in light of external constraints.

6 Management – What Needs to Be Done and for Whom? Conflicting Visions

During the 1990s, two opposing development visions brought about major management initiatives to deal with the conservation of the natural resources of the Pearl Lagoon basin. DIPAL, a bilateral funding initiative (between The Netherlands and Nicaragua), began its activities in 1994 and ended in 2001. The project was aimed at, “creating the conditions for improving fishermen’s wellbeing as well as the living conditions of their communities.” The project sought to achieve this by providing, “a sustainable use of the fisheries’ resources [based on] equal opportunities, and local participation” (Pérez and van Eijs 2002, p. 3).Footnote 39

Since its inception, DIPAL promoted a vision of management that emphasized the commercial use of the fisheries of the Lagoon. During its first phase (1994–1997), DIPAL devoted its activities to generate baseline information on the hydro-biological resources and the economy of the Pearl Lagoon basin. During its second phase (1998–2001), efforts were made in order to influence policy making, in particular with regard to the implementation of a management plan in the Lagoon.

CAMPLab, an IDRC-funded program inaugurated in 1993 through a research alliance between CIDCA (The Center for Research and Documentation of the Atlantic Coast, and affiliated with the Jesuit-led Central American University, UCA), national/local and international researchers, and various local communities, had the aim of developing a management plan for the Pearl Lagoon basin. The goal of CAMPLab was to, “develop a knowledge base to inform a formal management regime for the area’s coastal resources.” This regime was to be designed through a participatory methodology (Vernooy 2000, p. 9).Footnote 40

Both management initiatives somehow ran parallel to each other, with little instances of collaboration between them. During its second phase (in 1997) DIPAL proposed an “integrated” management plan for the fisheries of the Pearl Lagoon, which was later adopted as a government official regulation (Pérez and van Eijs 2002, p. 3).Footnote 41 However, the proposal was not widely consulted with the resource’s users, which reflected DIPAL’s top-down development strategy and intervention principles. The consequence was open ambiguity on the part of the fishermen in adopting the regulations established in the management plan and therefore its potential for managing the resources of the Lagoon has remained with marginal effect to the present day. In addition, the governmental agency that oversees the enforcement of fishing norms, INPESCA, lacks the human and financial resources to exert supervision and control in the fishing areas.Footnote 42

In 1998, CAMPLab also produced a management plan. The scope of the plan went beyond the aquatic ecosystems, to also include terrestrial resources, in correspondence with community consultations (Christie et al. 2000). The plan was “adopted” by the municipal government through a local ordinance. At the regional level – within the South Atlantic Regional Autonomous Council – representatives recommended that both DIPAL and CAMPLab management regimes be integrated and should result in a “unified” plan (Christie et al. 2000). This collaboration did not render positive outcomes, and relations between these organizations became “confrontational” (Christie et al. 2000).

By and large, the two management schemes still remain today as an illustration of opposing development views with regard to what needs to be done, with whom, and for what purpose in managing the fisheries of Pearl Lagoon (Table 13.3). In constructing management designs, the perspectives and participation of local communities are critical factors in determining feasibility.

6.1 Perspectives from Marshall Point

“Protecting the Lagoon? Indeed, but we cannot do it alone.” The research inquired about the responses of the people of Marshall Point to the management plans as designed and proposed by DIPAL and CAMPLab. The first noticeable finding was that, overall, community members were not able to distinguish between the two management proposals. Among fishers, references were made to the “DIPAL project” when referring to commercial fishing initiatives – which were widely promoted by DIPAL.Footnote 43 For CAMPLab, comments were made with regard to “workshops” on natural resources of the basin being held in the town of Pearl Lagoon or Haulover. Overall, few adults – mostly men – had participated in some of the meetings organized by DIPAL or CAMPLab. Technical details – about norms and regulations being proposed in the management plans – were largely ignored. Nonetheless, rather than stressing opposing interests between the two schemes, deep concerns were expressed with regard to the lack of implementation on the part of the government (municipal, regional, and national). The following comment from Manuela, a founding member of the Orinoco-based women’s cooperative, is telling:

I remember that was when DIPAL was working in the Pearl Lagoon area. Yes, I still have my management plan book from that time. No government came out strictly about it, they slack, and don’t care. You know what I got to say? Them eat bread with butter, so them have no interest in we the poor people. They are getting thousand and thousand (of dollars) and we no get nothing, and when the fish go away from we, they getting a thousand there in the office and we don’t going have fish, we don’t going have nothing.

It is also noticeable that Marshall Point’s inhabitants were not consistently consulted about management designs as proposed by the two development initiatives. This does not mean that residents opposed the idea of regulations and control over the resources of the Lagoon. On the contrary, during the research activities community members explored a variety of ideas for securing the resource base. These ideas ranged from completely banning resource extraction (through vedas, or closed seasons); using a number of selected techniques (gill nets) on certain seasons; limiting access to outside fishers (from Bluefields, or Rama); protecting distinctive reproductive areas; to locally managed regulations (Table 13.3).

However, management and ecological protection cannot be done by Marshall Point in isolation from the surrounding communities, and especially it cannot be done in the absence of a collaborative government. This view is clearly expressed by Herbert Bennett, a local fisherman:

I feel like, if the government and the people get together, with the people of the community, you have power. The community decides and the government put the force, because that’s the government. The community alone I don’t feel like we can get no way, we need the government. The government has to be in it.Footnote 44

Marshall Point has not had to wait for the government to take action. A multi-faceted, innovative approach for protecting the resource base of the Lagoon is underway. However, the rationale that informs the community’s strategies for coping with poverty are deeply embedded in peoples’ perceptions of poverty as well as on their assessment of the relative resource depletion.

6.2 Not So Poor, But Not So Rich Either

Having a secure, even if minimal, resource base for food supply, particularly fish and shrimps, is the key determinant for the community’s perception of someone being in a situation of extreme poverty. One is said to be “poor” if there is “nothing in the plate to eat.” This is a situation that, according to local perceptions, no family in the community has yet ever experienced. This is what places Marshall Point at a relative advantage with regard to other settings in Nicaragua – references are made to urban areas – which suffer from extreme poverty, and where there “is nothing to eat.”

In the community’s view, the relative availability of resources capable of providing some “food in the plate” is being threatened by internal as well as external practices and dynamics. For instance, local fishermen use detrimental fishing practices. Overfishing with gill nets by the few affluent families in town encroaches upon the rights of the local poor, and menace their livelihoods. As cogently stated by Uncle Pi:

You might have 20 (gill) nets and you put out the 20, and I might not even have a net, none at all, so when you put out 20 nets, you are harming me, because when the net go and set out maybe you catch 400 pound of fish and you have and I don’t have no fish. So my family starve, is that truth? You starving me and my family, when I go with my hook line there is no fish in the lagoon.

In local perceptions, poverty is more than just lack of access (and availability) to a (traditionally) stable resource base. It is also explained in terms of marginalization from relevant policy decision-making and politics at the municipal regional and/or national levels. For instance, over the last 5 years, there has been an increase in basic public services available in the community; in particular, electricity (established in December 2007), schools (elementary), a health clinic, and communication (through privately owned satellite telephone services). These services have not come as the result of the “good will” of the government or private providers. Community members explain that the majority of these are the result of active community’s advocacy before the government and non-governmental organizations. Other matters, equally relevant for the community’s well-being, are not easily subject to influence. For instance, achieving political representation in the municipal or regional governments is complicated due to exclusionary mechanisms that, according to local residents, reproduce historical marginalization.Footnote 45

6.3 Marshall Point – Coping with Poverty and Disempowerment – A Multi-faceted Strategy

As it has been explained, Marshall Point confronts a vulnerable situation characterized by undefined property rights, and internal conflicts over resource use that are the source of growing tensions, the exhaustion of the fishing stocks, and the continuous marginalization from decision-making of relevant policies. Facing these challenges, inhabitants have developed a variety of mechanisms with the purpose of coping with vulnerability and poverty. Livelihood strategies, as we would like to argue, make sense within a comprehensive scenario of agency and social power displayed by individuals, families, and community institutions. We have tried to illustrate this multi-faceted approach in Fig. 13.4:

Six strategies for this multi-faceted approach displayed by Marshall Point merit a closer examination: (1) strategies toward securing land and aquatic rights; (2) efforts in the direction of reorganizing a fishing cooperative; (3) shifting labor from fishing to agricultural production; (4) outward migration and educational opportunities; (5) accruing social and political power; and (6) implementing informal community-based actions to locally manage the resources of the Lagoon.

6.3.1 Securing Aquatic and Terrestrial Rights

For Marshall Point, securing unambiguous terrestrial and aquatic rights constitutes a leading livelihood strategy toward empowerment. Christie reports that the “concept of sea tenure does not exist in the strict sense” in Pearl Lagoon. He observes that, “each community has its preferred fishing grounds, but many of the most popular sites are used by a number of communities” (Christie 2000, p. 37). We did not observe this apparent lack of explicit definition of tenure over aquatic sources in Marshall Point. Though, the community’s sense of rights to the Lagoon’s waters and resources have undergone transformation due to reassessment of current perceived pressures over the resource base.Footnote 46

Today, Marshall Point has articulated a clear sense of rights over its terrestrial and aquatic area, and has eagerly pursued negotiations with Tasbapaunie to have these rights recognized “on paper.”Footnote 47 This is, once Tasbapaunie secures the title deed over its historical territory, Marshall will request its “own land.”Footnote 48 Such development will certainly increase the capacity of Marshall Point to oversee and protect its resource base. Currently, Marshall Point claims approximately 7.5% of Tasbapaunie’s territory (CCARC 1998, p. 335). It seems that Marshall Point’s communal authorities have expressed these concerns to Tasbapaunie’s territorial board and have found a positive response. As suggested by Uncle Pi:

Well the other day we had a little trouble, and some of the people got the other way and we ask for an amount of land (from Tasbapaunie), and to “give we the documents” and they say “ok, no trouble, we will give you’ll because you deserve it,” and we deserve it. They give us some paper that say you can take from Key Suta Point, from there come right to Justo Point, that is our mojon (recognized physical limit).

Over the last 2 years, Tasbapauni has experienced internal political conflicts that resulted in two competing territorial boards being elected. This has delayed progress toward land demarcation and has made communication with Marshall Point’s authorities difficult.

6.3.2 From “Grupo Solidario” to “Cooperative,” and Back to Just “a Group of Fishermen”

In 1999, DIPAL promoted the creation of grupos solidarios (or solidarity groups) among fishermen in Pearl Lagoon intended as organizational units supposedly suitable for commercial fisheries. These “groups” were basically a top-down imposed organizational model, with the purpose of channeling limited funding to supposedly “efficient” and “true fishers.”Footnote 49

In Marshall Point, the grupo solidario did not develop independently, and rapidly disbanded in 2001, once DIPAL concluded its activities. Outside-promoted forms of economic organization have been part of Marshall Point’s history. The formation of fishing “cooperatives” by fishermen had also been made conditional for receiving governmental loans during the first Sandinista administration in the 1980s. Once more, the new FSLN administration had promised to provide loans to fishers on the condition that they form a cooperative (Galeano and Silva 2009). Ignacio Casildo, a member of the fishing cooperative, sees this move as déjà vu with a twist:

They (the government) come to the fishermen and say “if you people need help all you have to do is to form a cooperative and make a project,” that how they say. So ok, we remember like in the 1980s with the government that was in power, is something similar: they didn’t ask for fifty cents. With this project, they say the bank will lend the money, but you have to get the group form so we gone through all that.Footnote 50

The cooperative is largely being formed out of the previously disbanded members of DIPAL’s grupo solidario. It does make sense for fishermen (and some fisherwomen) to get the group organized in light of imminent funding.Footnote 51 For community members, it is clear though that they are, above all, just “a group of fishermen,” with the aim of accessing funding and seeking local economic development. After submitting the proposal to government officers at INPESCA, the “project” was returned to the fishermen for amendments.Footnote 52 According to Asolin Chang, President of the fishing cooperative:

The project went to Managua. From Managua they send it back, because it was not complete, one of the questions from them was: where is the constitution of the cooperative? And, we don’t have that because we just forming it, this is just a group of fishermen, this is not a cooperative. The project what we send, is good but is not complete.

In synthesis, the fishing cooperative makes sense within the community efforts in securing capital assets in context of renovated opportunities for fisheries development. However, the government decision has not gone without criticism by community members who are not part of the “group of fishermen” – due to their lack of start-up financial resources which were set as a condition for membership.Footnote 53

6.3.3 Shifting from Fishing to Agriculture and Cattle-Raising – A Decision Not Absent of Conflicts

Within the livelihood strategies Marshall Point inhabitants have put forward, shifting labor from fishing to agriculture and cattle-raising constitutes a coping mechanism that is also infringing upon traditional norms and cultural arrangements with regard to resource use. Data generated from the survey indicates that more than 65% of households are now cultivating small plots of adjacent agricultural lands in the community. Interviewees suggested that, over the last 2 years, in response to rising food prices, households have returned to farming activities. Another reason given is the decreasing levels of fish and shrimps in the Lagoon in the dry season, when hook lines are commonly used by people who do not own gill nets.

At the same time, cattle-raising is on the rise and has involved some better-off families in town. Subsistence livestock has traditionally provided savings in time of illness or hardship. Besides, wandering cattle in the community “keep the grass at shape.”Footnote 54 Cows are rarely milked or used for local consumption, unless there is a necessity. However, pasture fields (potreros) have been established in areas commonly used for farming. Herbert Bennett complains that:

Now people make potrero and you can’t even open the man’s fence and get to go in. He say “this is my business” and like that then, and it shouldn’t be like that. That is what I crying about, but you hear, this thing is a big problem.Footnote 55

Cattle-raising is now developing in opposition to community norms with respect to the use of certain areas for agricultural activities. This competition over resource use also involves encroaching cattle-owners from the neighboring Orinoco.

6.3.4 Outward Migration and Educational Opportunities

As mentioned earlier, outward migration – in particular to temporary jobs on international cruise ships – has been a traditional practice that is used to supplement families’ income. This is a practice in which most communities in the Pearl Lagoon basin are involved. Indeed, for some families in Marshall Point, remittances now constitute the main source of income. In addition to outward temporary migration, opportunities for attaining higher levels of education have also been sought as a strategy for social mobility, and therefore to cope with poverty. To this effect, regional universities have also expanded outreach programs in the Pearl Lagoon basin, and scholarships have been made available to families.

6.3.5 Accruing Social and Political Power

Marshall Point’s coping strategies are not reduced to socioeconomic elements. Facing a new round of regional elections (to be held in March 2010), community’s authorities are also seeking to increase political power on supra-community levels. Political opportunities have opened up for Marshall Point in context with political parties trying to broaden their political base.Footnote 56 The community board has brought this question to open assemblies in order to strategize about taking advantage of these opportunities.

6.3.6 Community-Based Management Actions

The Pearl Lagoon basin constitutes a semi-open resource system in which customary norms and occasional state-enforced regulations exert some level of control over access and exploitation by outside fishers. Generally, communities do not oppose access to fishing grounds by the surrounding indigenous and Afro-descendant communities of the basin. However, communities believe that outside fishers should be subjected to taxation; or that eventually, access to outsiders must be openly denied. Indeed, some communities have pursued an active enforcement of these rules, as reported by some studies (Henriksen 2008).

In Marshall Point, access to aquatic resources by non-community members is subjected to constant evaluation and learning. It can be argued that, to some extent, the community approaches the matter with pragmatism rather than with permanent guidelines. For instance, some customary norms and regulations are in place – such as taxation if fishers or buyers from Bluefields or Pearl Lagoon enter the community’s waters. However, if the presence of outside fishers or buyers represents an opportunity for income generation by local fishermen, taxation would be omitted.Footnote 57

Community regulations indicate that fines should be issued over recurrent breaches of fishing norms – for instance, persistent omission of the required authorization on the part of external buyers or fishers. However, no fines have been issued since the community bylaws were approved.Footnote 58 Community members are more eager to oversee that certain fishing areas within Marshall Point’s territorial waters are not subjected to resource extraction. This is the case with a place called “the hole,” which is said to be a “cave” where fish reproduce and seek refugee from overexploitation. The “hole” is located approximately 4 km north of the community, close to the center of the Lagoon. Fishing at the “hole” with gill nets – even by surrounding fishers from neighboring communities – can cause intense disputes between local fishermen and would certainly involve other community members as well. Fishing with hook-lines at the “hole” is more often allowed during the dry season.

Fine-mesh gill nets (3 in. and smaller) are frequently used by some fishermen in Marshall Point. This practice contravenes norms stipulated in proposed management regimes both from DIPAL and CAMPLab. However, these fishermen confront increasing criticism from other members of the community who see such practices as a violation of their rights to access a sustainable resource base. Seeking to avert starvation, multi-family households that have limited access to fishing gears usually share them during the rainy season. The diagram below (Fig. 13.5) offers a composite of the six strategies displayed by Marshall Point. Rather than linearity, the idea is to represent the mutual reinforcement and cyclicality of the various strategies.

Marshall Point: reinforcing strategies. This diagram offers a composite of the six strategies displayed by Marshall Point. Rather than linearity, the idea is to represent the mutual reinforcement and cyclicality of the various strategies. Enforcing local norms on management depends on the positive interaction of internal and external factors over which the community has relative influence (for instance, securing access to land)

7 Conclusions

Marshall Point shares with other indigenous and Afro-descendant communities of the Pearl Lagoon basin similar concerns and challenges with regard to preserving a sustainable resource base for the long-run. Increasing over-exploitation due to commercial fishing has placed local fisheries on a critical path in their capacity for meeting this end. Livelihood strategies displayed by Marshall Point exhibit certain commonalities with adaptive strategies and trends observed in other communities in the area (for instance, finding jobs abroad or supplementing households’ income with seasonal work available in other parts of the region).

However, at the same time, the community seems to be engaged in pursuing strategies that are somehow qualitatively different from its counterparts. For instance, with regard to collective action toward securing terrestrial and aquatic resources as a means to increase political and social status vis-à-vis Tasbapaunie and Orinoco. This strategy also seems judicious in relation to increasing the political community leverage with reference to other sources of power in the area/region, such as seeking public office in municipal and regional governments.

Moreover, Marshall Point shows a creative integration of management regimes and locally managed norms in relation to fisheries. Enforcing these norms, however, seems to be shaped by a pragmatic and self-learning approach on the part of the community’s authorities. Specifically, community-based management, even if strongly supported by local fishermen and other resource users, might still be at a great disadvantage in context of increasing pressure and contestation over the use of natural resources in the Pearl Lagoon basin. A collaborative national state capable of reversing what is now a precarious governance environment is constantly invoked as a condition to the successful integration of management regimes in the area.

We suggest that Marshall Point’s capacity for coping with poverty should be understood within a social power and livelihood approach. Locally held, cultural understanding of poverty as a social relationship is keenly integrated by community members within an assessment of their capacity for satisfying tangible material needs. From this emerges a multi-dimensional concept of poverty, which we utilized in grasping Marshall Point’s strategies to cope and overcome poverty and minimize vulnerability. For instance, management systems that emphasize commercial fishing run the risk of not capturing the comprehensiveness within which a community creates and develops livelihood strategies. Within these strategies, fisheries constitute a crucial one, though not the only component for securing communities’ well-being. Diversifying sources for food production, targeting other fisheries, supplementing household income (by traveling abroad), and assigning priority on educational achievement (human capital) are all discerning strategies within the spectrum of possibilities that Marshall Point is exploring to overcome poverty.

Finally, we suggest the need to theorize livelihoods strategies to overcome poverty in connection with empowerment. As we have examined, by looking at Marshall Point livelihood strategies, to be empowered at the individual and community levels is to have the resources (material, political), the capacity (the leadership, consensus, and self-determination), and the opportunity (autonomous rights) to mobilize for social transformation. In this sense, we propose to conceptualize empowerment for fisher communities as an enabling process, through which higher levels of social power can be accrued.

From this theoretical insight, we can conclude that in coping with poverty, Marshall Point has been engaged in pursuing a strategy of empowerment “from below;” and in doing so, has drawn from a variety of available resources and opportunities. Some of these resources have been advanced by outside actors, others are locally-generated. This strategy has rendered significant gains for the community as a sociopolitical entity. Nevertheless, crucial challenges lie ahead in the pursuit for a more equitable distribution of resources within the community. Our study suggests that strategies to overcome poverty should then be thought of as having two levels: one that is external and another that is internal, that are intimately connected. Without taking both dimensions into consideration in tackling poverty, just marginal outcomes can be achieved.

Notes

- 1.

Vulnerability is understood here as “the degree to which a system or unit, such as a human group or a place, is likely to experience harm due to exposure to perturbations or stresses.” Kasperson and collaborators highlight three dimensions of vulnerability: exposure (to perturbations and shocks); sensitivity (of people and places, and the capacity to anticipate and cope with the stress); and resilience (ability to recover and adapt) (Kasperson et al. 2010, p. 236).

- 2.

All interviews were conducted in Creole English.

- 3.

This was particularly evident on issues related to community land rights. Our research team was invited to attend various community meetings in which a strategy for dealing with land claims was intensely debated among community members.

- 4.

For instance, with the support of the research project, a community workshop was conducted at the end of September 2009. This workshop was designed with the purpose of increasing local capabilities of fishermen and fisherwomen on cooperative management (legislation, operation, etc.). This topic seemed relevant for local fishers in the face of a promised loan on fisheries development promoted by government officers from the Nicaraguan fishing authority.

- 5.

The World Bank. Website: http://data.worldbank.org/country/nicaragua. Accessed 30 September 2009.

- 6.

The Contra War was sponsored by the US against the Sandinista Revolution that ousted the Somoza dictatorship in 1979.

- 7.

Human Development Index for 2009 can be consulted online at: http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/country_fact_sheets/cty_fs_NIC.html.

- 8.

Fish of commercial value include: snook (Centropomus spp.), catfish (Bagre marinus), snapper (Lutjanus spp.), stripped mojarra (Eugerres plumeri, Gerres cinereus), whitemouth croaker (Micropogonius furnieri), mackerel (Scomberomorus brasiliensis), crevalle jack (Caranx hippos), and coppermouth (Cynoscion spp.). In addition, five species of shrimps are found in the Lagoon: brown shrimp (Penaeus aztecus), white shrimp (Penaeus schmitti), pink shrimp (Penaeus duorarum), and Atlantic seabob (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) (Christie 2000, p. 32).

- 9.

For instance, Pérez and van Eijs note that the B. marinus, C. hippos, the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas), and sardines (Opisthonema oglinum) are predominant in the dry season (from November through April/May); while snooks, whitemouth croaker, black mojarra (Lobotes surinamensis), tarpon (Tarpon atlanticus), and mackerel can be found over the whole year. Though, they are also predominant during the rainy season (from May until October) (Pérez and van Eijs 2002, p. 21).

- 10.

The communities of Awas, Raitipura, Kakabila, and Tasbapaunie are mostly inhabited by Miskitu people; while Brown Bank, Haulover, the town of Pearl Lagoon, Set Net and Marshall Point have historically been considered Creole-inhabited communities.

- 11.

However, during the second period of field research, a small group in Mestizo families was given temporary permission by Tasbapaunie for lodgings and to cultivate a plot of land in the western part of the Lagoon. The nature of this informal agreement was not entirely clear to us.

- 12.

For instance, unofficial estimates from 1992 reports 4,749 Afro-descendants and indigenous inhabitants (Christie et al. 2000, p. 22). In the 2005 census, this population is 6,394 (Williamson and Fonseca 2007, p. 59). This is about 26% of the population growth in a 12-year period. In addition, local population, particularly youth, have engaged more intensely in migration abroad as temporary workers on shipping cruisers in the US. These data might be unreported in official national or regional censuses.

- 13.

Two censuses were conducted: the first in February, and the second in July 2009. Our data registered 30% population growth in Marshall Point between 1992 (Christie et al. 2000, p. 22) and 2009. Multi-family households characterize Marshall Point’s social structure. Our survey revealed an average of 6.5 persons residing per household.

- 14.

- 15.

Kukras indigenous peoples inhabited the area of what is now called Kukra Hill, south of the Pearl Lagoon basin. Ethnographic studies suggest that Kukras are now extinct. However, families in Marshall Point still track their ancestors to the “kukras” from the Kukra Hill area.

- 16.

Nicolas Gutierrez Bennett, locally known as Uncle Pi, personal communication, Marshall Point, 26 February, 2009.

- 17.

This data is based on historical accounts provided by the community’s elders. Local narratives made references to Mr. Henry Patterson from Pearl Lagoon (referred to as “Mr. Patisson”), who served as Vice President of the General Council of the Moskito Reserve (see Von Oertzen et al. 1990, p. 322).

- 18.