Abstract

Today, in France as in most European nations (Houard 2011; Scanlon and Whitehead 2013), housing represents a highly strategic point where the ideas of justice, redistribution, and democracy are at stake. On the one hand, social housing systems are impacted by European regulations. Social housing is a SGEI in Community law, and the future of social housing may be shaped by the decisions of the European Court of Justice, as the recent Dutch case shows (Ghékière 2011). On the other hand, the debates are colored by national situations. In one way or another, housing has fully entered the national public arenas as a political object, with the socioeconomic transformations leading to the revision of the representations and shape of the whole social question. Currently, the French-subsidized rental housing system is clearly at the core of debates and decisions involving a large range of actors. Caught “between inertia and change” (Driant 2011), the whole sector is in a process of revision under a range of pressures (Levy-Vroelant and Tutin 2010a, b).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

1.1 European Trends in Social Housing Systems

Today, in France as in most European nations (Houard 2011; Scanlon and Whitehead 2013), housing represents a highly strategic point where the ideas of justice, redistribution, and democracy are at stake. On the one hand, social housing systems are impacted by European regulations. Social housing is a SGEI in Community law, and the future of social housing may be shaped by the decisions of the European Court of Justice, as the recent Dutch case shows (Ghékière 2011). On the other hand, the debates are colored by national situations. In one way or another, housing has fully entered the national public arenas as a political object, with the socioeconomic transformations leading to the revision of the representations and shape of the whole social question. Currently, the French-subsidized rental housing system is clearly at the core of debates and decisions involving a large range of actors. Caught “between inertia and change” (Driant 2011), the whole sector is in a process of revision under a range of pressures (Levy-Vroelant and Tutin 2010b).

Given this situation, it is worth distinguishing the different issues that are currently a matter of debate. Most are not typically French; similar concerns are being discussed all over Europe. Beyond the heterogeneity of social housing systems (Ghékière 2011), major trends can be identified: the shift toward privatization and “residualisation,” the redefinition of target groups, the reorientation of public funding from direct subsidies (the so-called brick and mortar) to personal allowances, the concentration and hybridization of social housing enterprises (Mullins et al. 2012), and the inflation of fiscal incentives (Pollard 2010). A parallel and paradoxical process takes place: the legal strengthening of housing rights and the weakening of collective protections in the context of the changing missions of the State (Lévy-Vroelant 2011), and the capacity to successfully deal with the homelessness under question (EOH report 2011). Last but not least, housing has become a tool for urban policies, through intensive fund raising at the local, national, and now European level. The urban renewal process, which operates almost everywhere in Europe, also uses social housing as a tool to reorganize urbanity and the spatial distribution households with various degrees of achievement. However, the people’s effective power to choose their home and location remains uncertain.

1.2 The “French Model” at Stake

Such trends are also active in France where, as in other national contexts, path dependency determines specific configurations and answers (Lévy-Vroelant et al. 2013). The national distribution according to the tenure status is quite balanced: 56 % of households are homeowners (of which 80 % live in individual houses), 22.3 % are tenants in the private rental sector (70 % reside in apartments in collective buildings), and 17.3 % are social tenants (85 % live in apartments); 4.5 % have “other status” (such as furnished flats, free accommodations, etc.). Around ten million inhabitants live in a social housing unit.

The French social sector belongs to the “generalist” family (together with Austria, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Finland, Czech Republic, Poland, and Luxembourg) (Ghékière 2008). Such “model” is characterized by a large (but not universalist) targeting regarding the population to be housed, as well as the use of priority criterions. It also comprehends the domination of social landlords in the allocation process and the role of the State in providing funds and determining rent levels and income ceilings. However, such “model” is at stake. Contradictory pressures are operating in the social housing sector, which is required to be at the same time an instrument for implementing social cohesion, territorial equity, and the right to housing for all. Consequently, the population to be targeted, the level of prices, the relation between private and public supply, the implementation of the recently reinforced right to housing (Brouant 2011), the ongoing decentralization of financial and administrative powers, and the allocation process and its effects on both social and spatial equityFootnote 1 are crucial issues that, interestingly enough, are a matter of discussion in the academic milieu and among lobbying activists and have reached (again)Footnote 2 public opinion.

The French subsidized housing sector is a realm of various contradictions. In this chapter, we consider these contradictions as non-commonplace starting points. First of all, far from being on the decrease, the social housing stock is quite large not only in number (between four and five million dwellings, according the perimeter considered; see Sect. 13.3) but also in proportion to the total stock (17–18 % of households) and to the rental stock (around 44 % of rental housing units belong to social landlords). Conversely to the trend generally observed in Europe, the social housing stock does not tend to decrease and seems rather to be experiencing a revival. At the same time, it suffers a bad reputation and is currently blamed for functioning as a filter and excluding (or even discriminating) on the basis of poverty, presumed insolvency, or “ethnic” background. These concerns are put in fast-forward on the national and European level by defenders of the right to housing for all (Feantsa reports 2008, 2011; Comité de suivi DALO report 2012; FAP report 2013). Scientific literature has also largely explored such hypotheses (Sala Pala 2005; Wacquant 2008; Pichon 2011). Those approaches seek to demonstrate that the French social housing system does not fulfill the expectations toward more territorial equity (Blanc 2010; Jaillet 2011) or even that it participates, with the excuse of getting rid of ghettos, in discriminative processes through “local methods for managing local diversity” (Kirszbaum 2011). The de facto concentration of households with migrant backgrounds in “sensitive” and mediocrely maintained social housing areas reveal a “hidden” filtering process (not solely income-based) that challenges not only the “generalist model” but also the “Republican model” (which supposes indifference to origins under any circumstances). Finally, the role of the subsidized sector in accommodating the poorest and those “most in need” is in line with its mission of general interest, but the State representatives (namely the prefects) are not always in a position to impose their views on the outcomes of the allocation procedure. Are HLM to be burnt? Footnote 3 Such a provocative and radical implicit assumption associates the 2005 riots to the housing question; in doing so, it embraces the large range of concerns (and hopes) of which housing, and more particularly social housing, has become a symbol.

1.3 Building Coalitions: Discourses and Practices

The HLM system has its critics, as well as some enemies,Footnote 4 but in most cases, these critics do not intend to deny its necessity. Some are clearly targeting a reform that should improve the sector, and, emblematically, the attribution process is pointed out for its lack of transparency and fairness (Bourgeois 2012; Houard and Lelévrier 2012); others are advocating for a general revision of housing policies. Considering the high level of housing rents (social and private) as the main factor favoring increasing inequalities, some propositions are converging toward a joint mobilization of both public and private housing stocks to be opened to those most in need (Lévy and Fijalkow 2012). In this last case, it is no longer the housing unit that needs to be “social” (or better socialized) but the rent, with the duty of compensating for the shortage in rent falling to the State. However, beyond these critics, there is a remarkable consensus on the indisputable necessity of social housing that needs to be investigated in detail. Looking at the discursive practices of policy and decision makers is a rather promising way to make this understandable (Zittoun 2000, 2009). We consider that stakeholders’ actions and discursive activities are coherent and that one may shed light on the other. Additionally, framing the public opinion serves as a tool in coalition building, where actors have to convince (and combat) each other to achieve a consensus. The interpretative pattern usually accepted in describing the evolution of policies from the period after the Second World War fits into the current opinion that the social housing sector has weakened as a consequence of the loss of public intervention and the vanishing welfare state. It is necessary to go beyond such pattern because it closes the possibility to understand how the sector is carrying out transformation and adaptation and does not provide an alternative for the future but only expects a continuation of the current trend. Perhaps it would be more pertinent to reintroduce the terms of the debate, as well as the alliances along which social housing is being reconfigured, either from a defensive position or a more proactive one.

We start with the statement that the social housing sector in France, unlike what is often said, is far from disappearing and is still very strong, and we look for the explanation for such a situation (1). We then analyze the interplay of actors (national politicians, local representatives, social landlords, the State). In doing so, we put the HLM at the center and envisage the tools (both discursive and concrete) that the social housing sector explores and implements to cope with the new context and react to the new challenges (second part). The social housing responses and resources in dealing with change are then developed (third part). In the conclusion, we try to reinstall the debate in the larger context to specify the more important issues being raised regarding social housing in the present times, the first of which is its (probably insufficient) role in ensuring that “everyone should be housed.”

2 The Strength of the Social Sector in France

2.1 The French Social Housing Realm

According to the latest data from USHFootnote 5 (Union sociale pour l’habitat), out of the overall stock of 27.680.000 housing units (INSEE 2012), social housing, also known as HLM (habitation à loyer modéré), accounts for 4.5 million, and accommodating 16 % of households. The rate is actually 17 % because there are in total 4.8 million housing units submitted to income considerations regarding their allocation (or with a “social” purpose), including 320,000 dwellings belonging to the private sector and 350,000 belonging to the non-profit sector (but not HLM) (see Sect. 13.4); charities belong to a third sector and receive public support. While the number of private rented dwellings has remained almost constant, and private renting has decreased in proportion to the stock, the numbers of owner-occupied and socially rented homes have both roughly tripled since the 1960s. The weight of social housing in the economic and financial landscape is far from negligible, with an investment capacity of 17 billion euros and 160.000 employments provided, according to USH.Footnote 6 Since the 1960s, three distinct types of social housing have been produced, targeted at households of different income levels. There have been various programmes, each with its own acronym; the current ones are standard social housing (PLUS),Footnote 7 “very social” housing for lower-income households (PLAI),Footnote 8 and upper-income social housing (PLS)Footnote 9 (Lévy-Vroelant et al. 2013). The proportion of upper-income social housing in the total construction of social housing has grown (from 25 % in 2003 to 32 % in 2010), confirming the general shift toward more expensive rents (see Sect. 13.3), while the “very social” sector has become increasingly specialized and cut off from common and regulated social housing (Lévy-Vroelant and Reinprecht 2013).

About 85 % of social housing units are flats, and due to the recent history, half of the stock was built before 1976 (and one fourth, 1.12 million units, between 1966 and 1975). This legacy of the industrial period, also called the “three glorious decades” because of the economic growth that favored the democratisation of the “consumption society”, standardized domestic facilities and generated the “modern” way of living (and thinking) that now appears to be problematic. During the 1970s, more than 110,000 social housing units were completed yearly. Those estates are nowadays a matter of concern, not because they were intrinsically offering bad housing conditions but because the dynamic economic and social environment generating upgrades in social mobility had come to an end by the beginning of the 1980s. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, large estates of more than 500 dwellings represented less than 6 % of the stock nationally, and new construction was oriented toward small housing estates, except in the large cities, such as Paris, Lyon, and Marseille, where the densification of the urban fabric has become a new standard (and a discursive common place) in relation to the energy consumption concern. At the same time, the share of individual houses is increasing, accounting for almost one fourth of new production. The average size of new social housing estates is around 23 dwellings per building.

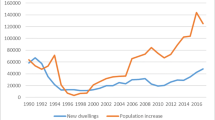

After the 1970s, social housing construction went down (to less than 50,000 by the turn of the century). However, since then it has increased remarkably. “The net balance (construction minus demolition for urban renewal and 5,000 sales to tenants/year) was above 50,000 in 2011, which makes of France the only European country (with Denmark) where the social rental stock is increasing both in absolute and relative terms.” At the same time, the funding of the current ambitious program (150 000 per year) appears to be quite uncertain.

2.2 Social Housing: A Historical Consensus

The social housing of today (and plausibly of tomorrow) remains framed within a specific historical pattern. French social housing has its heroes, emblematic places, and, under these idealized images, a project for solving the conflict between labor and capital. The French system has developed on the “traditional” ground of (1) centralized governance, (2) a strong individualistic ideology favoring individual property and responsibility (the famous slogan “enrichissez-vous” (“get richer”) launched by Guizot, head of the King Louis Philippe’s government in 1840), (3) division between assistance (charity and philanthropy) and insurance (gained through class struggle), and (4) dominance of entrepreneurs as crucial economic stakeholders. In short, between 1850 and 1912,Footnote 10 the French understanding of the relation between State, civil society, companies, and financial power led to a set of laws and dispositions that enabled public authority to intervene in the “private” domain of housing. Obviously, the legal system plays a role (and is reflected) in the definition of the mission of social housing. In the case of France, the Civil Code and the following legal dispositions clearly distinguish between private ownership and renting, with the first considered as superior and almost unlimited by law and as a social norm. All together, these items (superiority of home ownership, ancient centralized governance, powerful entrepreneurs, charity as ultimate safety net) are reflected in social housing outcomes and in one of their more emblematic features: “where allocation there [in France] is dominated by representatives of local interests empowered to refuse disadvantaged people” (Ball 2008).

After the devastation of the Second World War, housing became part of the welfare state duties. Supportive political and economic decisions have been undertaken in Europe rather simultaneously, including the use of housing for welfare purposes. The HLM Act (1949) was enacted to ensure decent housing conditions for “the wage-workers and their families.” In France, perhaps more strongly than in other countries, the social housing history has been parallel to the country’s industrial and economic development. As a consequence, the social stock is concentrated in large cities (Paris, Lyon, and Marseille) and former industrial areas, such as the coal and iron mines and textile industry centers of the first industrialisation period (northern and eastern parts of France), as well as in large cities’ suburbs and in “new towns” developed according to a centralized master plan from 1965 in order to counterbalance the Paris region’s dominance. In terms of urbanism and architecture, the ideas of the modern movement (Le Corbusier) are fully mainstream. Two thirds of the existing social stock is located in towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Most of these locations now suffer from the economic crisis and the general mutation of the production process. They then cumulate socioeconomic handicaps and experience geographic isolation, with dilapidated or badly maintained urban environment and housing conditions. This situation has led to an important shift toward the “politique de la ville” (“urban policy”) decided, ruled, and monitored at the central level by agencies such as ANRUFootnote 11 and symbolized by the creation of the so-called “sensitive urban area,”Footnote 12 where 7 % of the French population (around 4.4 million) live and which is mainly characterized by the importance of the social housing stock, 60 % on average (Chevallier and Lebeaupin 2010).

French subsidized housing is also characterized by the importance of the supply provided through the intervention of enterprises. From the beginning, as previously noted, companies have been keen on providing social housing to their workers in order to control them and improve productivity by securing their living conditions, besides philanthropic reasons. In the reconstruction era (1953), a “1 % tax” on wages was introduced to provide ring-fenced funds for housing investment. In 2011, “Action Logement”,Footnote 13 which owns 785.000 social and intermediary housing units (in ESH form, see below), counted up the total income from enterprises’ participation as 3.5 billion euros. The major part of urban renewal actions has been supported through Action Logement funding (to ANRU and ANAH).Footnote 14

2.3 USH and Its Components: Social Housing Organization and Financing

Social rental housing programs are owned and managed by two main kinds of providers that fall under the remit of the umbrella organization Union sociale pour l’habitat (USH): OPHLM, public agencies (offices publics pour l’habitat) chaired by local authority representatives; and ESH (entreprises sociales pour l’habitat). Semi-public organisms (SEM) also intervene in the supply (SEM and charities accredited through “public service mission delegation”), as do individual private landlords who take part in the social provision because they have benefited from the large fiscal incentive for purchasing a dwelling, which they have then rented out under social conditions (lower rents). Of the total 4.77 million dwellings delivered under income conditions, as shown in Table 13.1, HLM bodies are dominant, representing 86 % of the supply.

The HLM bodies also manage foyer furnished rooms (around 300 000); these are very specific to the French system, which since 1954 has provided separate accommodations for immigrant workers (the so-called Foyers de travailleurs immigrés, FTM) and young workers (the so-called Foyer de jeunes travailleurs, FJT) to facilitate internal migration during the period of huge economic growth (Lovatt et al. 2006).

An additional portion (around 800 000 dwellings) is considered as social because it offers rents below the market rates. This supply has heterogeneous origins: one part is provided by municipalities and the State, and the other is composed of the stock covered by the so-called “1948 law,” which was enacted in 1948 to block the inflation of rents for the existing stock while liberating newly built units and stimulating the market. As a result, part of the ancient stock retained low rents and remained accessible to anyone, whereas the new construction market was stimulated. Recently, this law has been suppressed (with tolerance for older occupants). Also called the “de facto social housing provision,” this sector has played a very important role in the integration of the modest-income population, and its disappearance (also due to intensive real estate speculation: more than one million units covered between 1985 and 1995) must be mentioned as a factor that worsens the shortage of affordable housing. As a whole, subsidized housing amounts to around six million dwellings. From the structure of the whole sector, one can observe the importance of HLM bodies, the very minor role of cooperatives, the (growing) importance of the “very social” part, and the mixing of legal forms between public (OPHLM) and private (individual private landlords).

In brief, the strength of the HLM system lies in its long history, in the collaboration between a large range of stakeholders, including economical and financial ones, in the strong nationally driven regulation, in the durable consensus on the necessity to activate the construction sector, and in the large support from public opinion. Interestingly enough, social housing is considered as necessary and even indispensable in order to implement social justice and solidarity, but its reputation is not good enough to make it desirable: social housing is good, but for the others. This leads us to consider the challenges that the sector has to face.

3 Challenges

3.1 Social Housing Tenants: Still a Diverse but Impoverished Population

Having acknowledged the diversity of the social housing system, one would easily agree that the different social organisms will not encounter the same type of challenges and that the location will also matter a lot. It can even be an artifact to consider social housing as a whole. Still, we need to know to what extent the households living in social dwellings do belong to the most “in need” section of the population.

According to INSEE documentation, “in 2002, households in the four highest standardized income deciles amounted to 20 % of social housing residents. This proportion, albeit not negligible, is lower than ever (30 % in 1984). High income social housing residents enjoy on average much better housing conditions than poor ones. Nor do the former live in the same districts as the latter” (Jacquot 2007). This means not only that the social tenants have become poorer but also that the sector is fragmented between the provision of good quality and attractive location and that of dilapidated and stigmatized housing, with a large variation between these two extremes. This trend is not new, as Fig. 13.1 shows, but has been reinforced in the past years, with the new tenants (residents for less than 3 years)Footnote 15 having a lower level of income than those in place and with the territorial inequalities having increased.Footnote 16

3.2 One or Several Social Housing Sectors?

The structure of the households also reveals the social housing sector’s specificity: less couples, much more single-parent families, and also more dependent children; these trends have been accentuated in the last years. However, there are large differences according to the location, and the type of provider, as Table 13.2 shows. The non-HLM social housing sector (the park owned by semipublic and private social landlords) tends to be more similar to the national pattern, with couples with children being more numerous there than in the HLM sector (31.8 % versus 26.1 %); the same trends also hold for couples without children (13.4 % versus 15.3 %) and for single-parent families, which are expectably less numerous than in the HLM sector (17.7 % versus 19.2 %) despite being double the average in France (8.2 %).

Moreover, the social housing sector as a whole is not accommodating all households “in need”: a large part of these households are housed in the private sector or own the flat where they live. Based on the distribution according to tenure status of the 6.9 million households considered as low-income,Footnote 17 2.9 million own their flat (representing 20.4 % of owner-occupied housing), 1.9 million are accommodated in the private rental sector (36 % of the whole private rental market), and 2.1 million are present in the social sector (about half of social tenants). Even if the sector tends to accommodate more and more of the impoverished population, the lowest incomes are also distributed in other types of occupancy status.

3.3 The Mismatch Between Demand and Supply

According to the recently published FAP annual report (FAP 2013), there are currently 1,179,857 social housing applicants (including the demand for internal mutation in the social sector), among which more than 400,000 are in the Paris region, where the tension is extremely high. In addition to the imbalance between demand and supply, the social housing allocation procedure is intrinsically opaque. Involving parties with reservation privileges, stakeholders of different kinds, and representatives of local authorities and (in theory) of the State, the Commission that rules on final attribution is often deemed discriminatory. Besides that, and in spite of the shortage, the application process sometimes results in refusals from the applicants when an offer comes. The USH has ordered a research to better understand the reasons for these refusals, which contribute to hampering the whole system.Footnote 18 The findings point to the existence of repellent dwellings that are difficult to rent out mostly because of their location. In addition, the refusals are also addressed to new and well-located housing, in which case the smaller spaces and higher rents discourage the applicant from accepting the offer. The new context of social housing production (increasingly through public-private partnership) negatively impacts “commercialization” because social landlords can lose control of the timing of the process. Finally, the applicants, who sometimes have to queue for years, could become aware of the market and develop different strategies; that is, refusals can happen simply because the applicant has changed his mind in the meantime.

The mismatch between offer and demand is also reflected in the difficulty of adapting the size of the household to the dwelling: there is a substantial fraction of social dwellings that are either under- or overcrowded. The numbers are difficult to estimate for several reasons, but generally, undercrowded units (650,000–800,000) are inhabited by elderly people do not vary according to the city size, whereas overcrowding (about the same number of dwellings but obviously concerning much more people), which touches mostly families with dependent children, displays a high prevalence in large cities and is associated with a low standardized income and unsatisfactory housing conditions (Jacquot 2007). Additionally, the proportion of inhabitants in place for less than 3 years in the total of social tenants is decreasing, down from 33 % in 2000 to only 27 % in 2009. The decreasing turnover, accentuated in the public sector (vis à vis the private one) and especially in large dwellings (three or more rooms), is both a result and a cause of the sclerosis of the housing provision dynamics. The rigidity of the allocation procedure can be considered to be aggravating the situation to a certain extent.

3.4 Less Public Direct Funding, More Fiscal Incentives

Preferential loans, granted by a specific bank (the Caisse des Dépôts et consignations, CDC)Footnote 19 are the main tools for producing social housing. The low interest rate is crucial, but even more important is the loan duration (usually 40 years). Besides the specific loans, social housing financing is a mix of subsidies, fiscal incentives, and consolidated equity capital. The nature of this mix has changed a lot over time. As a result of the move from brick-and-mortar subsidies to demand-side policies initiated in 1977, direct grants to social housing from the state budget are now limited. Consequently, additional funding is to be provided by municipalities (under direct subsidies or provision of cheap land), which makes it harder and uncertain for the social enterprises to achieve balanced budgets. However, at the same time, HLMs pay a reduced rate of VAT (7 % instead of 20 %) and benefit from a 25-year property tax exemption and from growing fiscal deductions so that one can consider that fiscal incentives have become the core of housing policies: between 1984 and 2006, direct subsidies to construction (brick-and-mortar subsidies) have moved from 49 to 18 % (5.1 billion euros), whereas personal subsidies (to households) have moved from 34 to 51 % (14.7 billion euros), and fiscal deductions from 17 to 31 % (9 billion euros) (Pollard 2010) (Fig. 13.2).

To enlarge the supply and allow individuals to build up their assets, various fiscal incentives have been offered.Footnote 20 In exchange, investors had to agree to rent ceilings and minimum rental periods. These programmes have contributed to the provision of more affordable housing to quite a large extent (Pollard 2010), but this new provision’s results are random, not sufficiently targeted both socially and geographically, and primarily benefit private investors. Besides the acknowledged trend consisting in the switch from brick and mortar to personal allowances (the latter still go to the social landlord as a complement to the rent), the other important shift is the generalized use of fiscal incentives, which appears to be less transparent, less controllable, and less socially fair. With market deregulation or reorganization (public-private partnerships, concurrence in the social sector itself, changes in the characteristics of the provision, etc.) and permanent intervention (social benefits, tax policies, real estate construction governance, etc.) being two faces of the same coin, the objective is then to analyse properly this apparent paradox by identifying the stakeholders’ actions and discourses, as well as the alliances they establish among them.

3.5 Providing Territorial Equity and Right to Housing: Trying to Square the Circle

Social housing bodies are now in a delicate position because the change in funding sources forces them to liaise with financing consortia and negotiate for each project. They have to meet each financer’s expectations (type of housing units, rents levels, environmental concerns). Because the central government has contractually delegated the distribution of brick and mortar to local authorities, the latter are in a position to rule on projects and again become prevalent in the game. “This handover has partially altered the social housing production landscape by making more room for local and regional plans to increase available capacity. That was how in the name of ‘social mix,’ ‘urban renewal’, and ‘controlled urban development’, social housing production processes have been greatly diversified over the past decade, giving rise to new issues such as housing replacement, diversification and density management, in the agenda, alongside the original goal to merely increase capacity” (Driant 2011, p.120). In other words, social housing enterprises have been “invited” to enter the urban renewal market, a highly competitive environment, and to act as a tool for the implementation of urban and social policies. They execute demolitions (18 000 in 2010), behave as developers, or even buy from developers: since 2000, social housing organisations have been authorised to buy housing units built by private developers and sold-off plans (Vente en état futur d’achèvement, VEFA), which has been the main sale option for French property developers since it was established in 1967 (Driant 2011).

Simultaneously, the main actors in housing policy (government, local authorities, national social housing federation, NGOs, experts, and media) have pushed for (or accepted) an enforceable right to housing. The so-called DALO ActFootnote 21 was debated on with passion (Was it a good means to improve the rights of those who could hardly access any right?) and voted on in 2007. When the time came to assess the situation, both hopes and frustrations were found to result from its difficult implementation. Emblematically, the 6th report of the monitoring committee published in November 2012 is entitled “Rappel à la Loi” (“Reminder of the Law”) and showed unequal and dissatisfactory implementation (Houard and Lévy-Vroelant 2013). When the enforceable right to housing started to be considered by the government (2005), most local authority representatives were anxious that they could become individually accountable and that the State was taking an opportunity to shirk its responsibilities. The USH was internally divided. With the impoverishment of a portion of the social tenants, the “fight against the ghettos,” and the call to provide poor people with housing solutions, the introduction of the enforceable right provided an opportunity to strengthen the image of HLMs as “providers of housing to the poor” (Houard 2011).

3.6 The Bad Reputation

In the context of post-welfare policies, social housing is then also concerned with urban policies. A large proportion of immigrants live in large social housing estates, which are precisely those targeted by urban renewal policies. Approximately more than one in five social housing units are located in ZUS. Social housing is thus officially connected with images of dilapidated urban landscapes and social exclusion and has become a top political priority. The rhetoric of the “ghetto” is used to support ideologically the vast (and sometimes contested) implementation of urban renewal policies, using and abusing the social mix rhetoric.

A victim and guilty at the same time, the USH pleads, with some reasons, for its social necessity. The representation of social housing in public opinion perfectly fits into this double-faced feature, as shown in a recent survey ordered by the USH,Footnote 22 in which 80 % of those interviewed regarded social housing as a necessity, and 74 % agreed that social housing has a bad image. On the one hand, social housing is popular because it is associated with security (of tenure) and the idea of the State as a provider of a certain level of protection and wealth. On the other hand, social housing is connected with negative representations. The impoverishment of the tenants and the spatial segregation associated with criminality nurture a bad image of the sector. The displacement of social policies (non-territorialized) into urban policies (territorialized) contributes to the negative reputation of social housing neighbourhoods. A boomerang effect is to be expected because urban renewal programs particularly target areas that include large-scale demolitions,Footnote 23 with the reduction of antisocial behaviours and criminality as official targets.Footnote 24 Additionally, the bad maintenance of most large estates built in the 1960s and 1970s (and sometimes even more recently) is a matter of deep frustration: successive national housing surveys show that social housing tenants have a higher degree of dissatisfaction. A last line of huge critics, with evident political background, targets the “privileged” part of the sector, which is well-located, well-designed, and still affordable, and points to it as a realm of uncontrolled clientelism and social injustice. Even so, social housing is considered as a common good that needs to be preserved.

4 The Social Housing Sector’s Retort

4.1 USH Gets a Handle on Its Destiny as a Mainstream “Social Housing Market”

The goal of accomplishing a “mission of general interest” is at the core of the USH communication strategy. The USH home page insists on the values, meaning, and coherence of such mission, especially in a context of increasing economic and social frailty combined with the inflation of real estate prices and rents on the private market.Footnote 25 A key sentence is: “Social housing’s mission is essential to preserving social cohesion and for a better ‘living together’”.Footnote 26 The notions of solidarity, quality, and affordability, as well as of social mix, progress, and sustainable development contribute to the positioning of the USH as an alternative and indispensable “social housing market,” “benefitting one French in six.”

The rhetoric is quite habile in combining the contradictory challenges of serving social cohesion (being attractive and mainstream-oriented) and implementing the right to housing (showing solidarity and targeting those most in need); however, the emphasis is definitely on the first: “social mix depends on the political will to promote, in a given geographical area, diversity in terms of socio professional categories, standard of living and/or lifestyle.” This topic is balanced by the emphasis on housing a large part of low-income households and, consequently, on promoting solidarity: “one third of social tenants households earn less than 795 euros per month/person.”

The second argument goes back to the very origins and presents social housing as a pioneer in the field of architectural and technological innovation. Only the issue has changed; instead of promoting comfort and modern living standards (as was the case from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s and then again in the 1960s), energy saving has become a new paradigm: “85 % of the new social housing units receive the label of energetic performance.”

The third argument refers to the general interest and is double-sided. On the one hand, social housing serves as a cost-of-living insurance that enables households to participate in the consumer society, “enabling their goods and services consumption and their participation to local economy.” On the other hand, the emphasis is put on the economic importance of the sector as a provider of employment on the French labor market: “the construction of one housing unit represents the creation of more than one non-relocatable employment on the national labor market.” This last argument is certainly very powerful in coalition building.

4.2 The Agreement on Production and the Coalition Building

The objectives of the government (the call for more public money as direct investments and for recognition of the leading role of social housing in urban renewal) have received continuous support in the last decades, even though conflicts between the USH and the minister in charge of housing under the Sarkozy presidency have been highlighted by media. Today, nearly all the political parties in France consider it necessary to increase the production of new housing units. This option is clearly connected with the aim of reconfiguring neighbourhoods and achieving “social mix” and “social cohesion.” Under these different aspects, as previously discussed, social housing is central. The choice of a member of the Green Party as minister in charge of housing (Cécile Duflot), may indicate the political will to combine environment concerns with the promotion of the construction. The current minister is in a position to push the sustainability issue as well, that is to say, to promote renovation instead of placing the whole bet on construction. However, the discourse remains very much production-oriented (with 500,000 new housing units/year as a repetitively announced objective), and the discussion now focuses on the share of social housing in the whole target (150,000 units) and, significantly, the proportion of “more social” housing (that is to say, those funded through PLAI and with lower rents) to the whole.

It is worth mentioning that the argument has been taken up at the European level. The promotion of social housing as “a lever for helping the European Union to end up with the economic, social, and environmental crisis” is making way.Footnote 27 The social housing federation’s efforts to restore and improve its image can then be interpreted as a way to overcome the contradictions and challenges it has to face.

4.3 Changing Image and Reputation

As previously discussed, social housing as a whole has to tackle different negative representations. The first one is linked to images of dilapidated, insecure, and poor neighbourhoods. The challenge is to break down the stigma. In this regard, a large communication strategy is organized, sometimes with the commitment of the State or the local authority. Rich documentation is actively distributed during the urban renewal operations. At the national level, a document is proposed, with the idea of “tackling 10 prejudices” about social housing. Interestingly enough, those prejudices all refer to the capacity of social housing to remain attractive or improve its attractiveness. In brief, the arguments are trying to cope with negative perceptions, which are those delivered by the “ZUS” label (noisy, crowded, located nowhere, ghettoized, anonymous, and banal), and to turn them upside down to promote the potentials of such supply in a disorganized market: greenness, conviviality, energy saving-orientation, and last but not least, professionalism, openness, and anticipation capacity. The eco-quartiers Footnote 28 are emblematic of such positioning. The USH quarterly journal Habitat et Société reveals the main knots and hopes of the social housing sector and shows how strongly the USH desires to deal with societal changes and be seen as a progress builder and lifestyle inventor in terms of young people’s housing, mixing of communities, aging and housing, and gender and housing, among other issues. The USH is also very habile in converting its leading role during the past century’s housing history into a symbolic capital. However, all these go together with the reconfiguring of the financial and managerial organisation of social housing organisms. This is definitely the strategic aspect of the on-going changes, considering that social enterprises, and primarily social landlords, have to successfully combine social and commercial goals.

4.4 Reconfiguring from Inside: Concentration, Hybridization, and Diversification

In 2007, a reform took place, and the historic OPHLM (municipal housing bodies) had to merge with the OPAC (public habitat bodies) and create a new structure, namely OPH (Office public de l’habitat). Beyond changing the labeling, the reform basically consisted in providing an optional choice for private accountancy in order to better fit the new obligations resulting from locally driven governance. In doing so, the Offices’ management rules become more adapted to partnerships involving private companies.Footnote 29 Private operators can then enter the social housing market provision through public-private partnerships and acquisitions in VEFA. Middle-sized Offices are increasingly merging with each other or creating larger associations as a way to share technical departments and expertise in land, building, and commercial action (the newly composed “Paris Habitat,” for instance, deals with 115,000 housing units).

To anticipate the diminution of direct funding, the 761 social housing organisations have also entered a process of mutualisation of their assets and equity funds. As stated by Marie-Noëlle Lienemann, the minister in charge of housing in the last socialist government and currently the USH interim president, “not a single euro must sleep in the cash of one single HLM body” (73th USH Conference held in Rennes in September 2012). The consensus on the “optimal use” of capital equity is not so easy to realize due to competitiveness and diverging management options among the different organisms. Social housing bodies have therefore been reassessing their property portfolio management strategies and negotiating social benefit covenants with central and local governments. The employers’ participation in social housing also shows the connections and collaborations between “social partners.” The enterprise “Foncière Logement” is a result of public-private partnership. Funded mainly through Action Logement (fuelled by employers’ contributions, formerly at “1 %”), it proposed “good standards housing” for wage workers whose enterprises participate in the employers’ collection. The participation of Foncière Logement in the process of social housing production is emblematic of the recent orientations: in partnership with VINCI Construction, Foncière Logement buys the housing products in VEFA. In doing so, it opens preferential loans, such as PLS, with the private investor. Hybridization results in new competing organizational logics, trade-offs between social and commercial goals, and resource transfers (Czischke et al. 2012). It extends the boundaries of the playground to developers and investors.

In this context characterized by accentuated concurrence, and the “enabling state”-oriented governance, private developers (under SCI, SACI, and SCCV)Footnote 30 have become the more dynamic stakeholders in real estate construction. In 2005, they covered a third of the whole production. The share of public supply (social housing providers, local authorities, the State) in the housing production is now around 10 % of the total (compared to 25 % in the mid-1990s). Moreover, the usual credit tools dedicated to social enterprises are now open to private ones in the context of the urban renewal program. As well described in VinciFootnote 31 documentation, the urban renewal program is an excellent playground for investors: “Since 2005, the funds allocated by the State to the Urban renewal program have contributed to stimulate the real estate construction, where VINCI intends to strengthen its position.” In this context, social housing as a “product” serves, according to VINCI rhetoric, both private and general interests: it is a fructuous market allowing good profits and contributing, through social provision and more diversified “housing products,” to the implementation of social cohesion. In this context, too, the conflict between stakeholders is related to the concurrence between developers who are pushed to seek out more convenient partnerships. On the side of social housing bodies, the recent transformation (2007) of their legal status, which enables them to adopt the rules of private accountancy and management, as mentioned above, goes together with the incentive to contract with the State and territorial authorities and to adopt the regime of calls for bids and offers. European regulations, which encourage privatisation “under control” of social goods, play in the same direction (Ghékière 2011).

5 Conclusion

Since the last decade of the twentieth century, the French HLM system has been undergoing a metamorphosis. More recently, these transformations operate in a context where housing prices and rents have become increasingly unaffordable. French households are on average much better housed today than three decades ago, but the gap between those who can afford and those who cannot is increasing. In large cities, the concern is less about the housing shortage than on the uncontrolled level of real estate prices. The speculative bubble did not have the disastrous consequences verified in other countries. However, many issues, such as mobility and changing lifestyles, young people’s needs, environmental stakes, and spatial inequity, combined with shrinking labour markets, have not found a satisfying resolution. The housing market is segmented and instable, especially in the Paris area and the largest cities. Households are rather expected to pay the full price and consent to personal sacrifices to secure themselves through homeownership. At the same time, the unequal participation of social groups in the distribution of goods is a matter of great concern that goes beyond the homelessness question. The achievement of “housing for all” does not seem to come any closer. Behind the housing question, the social question has reappeared.

At the same time, a “new deal” seems to be currently at work, displacing the mainstream historical relations between stakeholders and incorporating a new modus operandi. In this configuration, the State is no longer fully the leader or provider. It has become a facilitator that enables private actors to participate on the floor, while “social partners” alternate between protest and cooperation. In such context, the role of the social housing sector is crucial and, more than ever, symbolizes public concerns and hopes. While concentrating on and strengthening its assets, the sector is also currently reconfiguring its identity. Under the cover of mutation of financial devices, the reforms have reshaped the sector and reconfigured alliances; they have blurred the borders between the traditional subsidized sector and the private one, as well as fragmented the social housing provision. On the one hand, this has contributed to moving the two sectors closer to each other; however, it has also rigidified the housing provision into separate and competing markets. Actually, the main point is probably the continuity of a secular trend. In contrast with the idea of a “neoliberal” turn, it seems that ancient alliances between building companies, the social housing sector, and the government are gaining strength again. At the moment, the government is studying a way to increase and generalize fiscal facilities and to reduce the VAT from 5.5 to 5 % in social construction (and the renovation of dilapidated buildings), with a possibility to renounce the VAT increase for the whole building sector (from 7 to 10 % in 2014). Different contexts, different tools, same objectives: similarly to the decades following the Second World War, housing is a leading element of the whole economy and urban (re)development. Building has become a goal in itself as an instrument to tackle unemployment and boost economic growth. In this respect, social housing is in a good position.

The debate about how public money and common goods should be collected, allocated, and redistributed has nevertheless gained renewed importance. In spite of its efforts and strength, the social housing sector alone does not seem to have the capacity to meet housing needs or to insure the right to housing. In the near future, the more important task could be to re-embed the housing question into the achievement of the general interest. The social housing sector, with its legacy and legitimacy, could then play a leading role again, on condition that it operates under enlightened democratic control. After all, European social housing of the origins has been a leader not only in terms of security of tenure but also in architectural innovation and social integration. The question is certainly not whether to throw the baby out with the bathwater but rather how to re-enchant it. Recasting the social realm will entail discovering new forms of social property that are likely to guarantee that housing is something that everyone, in both the present and future generations, can enjoy. Precisely because the economic, biological, and natural environments are instable, and the resources of energy and space are limited, individualistic approaches to property, protection, and sociability need to be challenged by alternative ones. A much greater range of habitat possibilities regarding conception, construction, tenure, financing, lifestyle, and social relations must be explored. From this renewed knowledge and collective imagination, solutions may appear.

Notes

- 1.

In France, the “spatial equity” paradigm has been approved through the nomination of the ministry in charge of housing, called “Ministère de l’Egalité des territoires et du logement” (Ministry of Territories’ Equality and housing).

- 2.

As in the postwar period (1950s and 1960s), during which housing was regarded as a national concern in opinion, if not in policy.

- 3.

According to a recent book: Lefebvre J.-P., Faut-il brûler les hlm? De l’urbanisation libérale à la ville solidaire, Paris, l’Harmattan, 2008, 392 p.

- 4.

Mostly, the Private Real Estate Professionals’ Union (UNPI) has been accusing social housing enterprises of distorting fair concurrence, and it has actually lodged a complaint against social housing with the European Commission.

- 5.

The USH is the umbrella federation of the 761 social housing bodies that make up the sector. See USH Données statistiques 2012, http://www.union-habitat.org/sites/default/files/Donn%C3%A9es%20statistiques%202011.pdf, consulted 4/01/2013.

- 6.

- 7.

PLUS for Prêt locatif à usage social (rental loan with social use); 68 % of households are eligible.

- 8.

PLAI for Prêt locatif aidé d’intégration (rental loan for integration); 31 % of households are eligible.

- 9.

PLS for Prêt locatif social (social rental loan); 82 % of households are eligible.

- 10.

1850: the first law in favor of public health allowed ad hoc commissions to enter the domestic realm to tackle unhealthy housing situations. The Expropriation Act in the name of general interest soon followed. Around 1900, laws enabling social housing were voted on; the Bonnevay Law in 1912 is considered one of the most important because it created the municipal social housing companies (HBM, the predecessors of the current HLM).

- 11.

ANRU (Agence nationale pour la renovation urbaine) is a powerful agency that organizes, promotes, and funds urban redevelopment in delimited areas (ZUS, sensitive urban areas, and those decided at the government level according to the PNRU (Plan national pour la renovation urbaine); around 40 billion euros worth of investment in 2004–2013). France is now entering the Second PNRU, with uncertainties regarding funding.

ZUS, see Observatory of French Sensitive Urban Areas, 2011, http://www.ville.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport-onzus-2012.pdf, consulted 3/02/2013.

- 12.

ZUS, see Observatory of French Sensitive Urban Areas, 2011, http://www.ville.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport-onzus-2012.pdf, consulted 3/02/2013.

- 13.

“Action Logement” is the new name of the ensemble composed of 31 CIL (Comité interprofessionnel du Logement).

- 14.

ANAH stands for Agence nationale d’amélioration de l’habitat, which is in charge of improving the private stock. In 2012, 341 million euros worth of housing units improvement were distributed were distributed. http://www.anah.fr/

- 15.

Called “aménagés récents” (recently moved in), they refer to a category used to measure changes in the French National Housing Survey.

- 16.

The data used in this section are mainly from Enquête Occupation Parc Social, DGALN, 2009, exploitation CRÉDOC, http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/tome1c.pdf (consulted 5/02/2013), and the last ONZUS report (Observatoire national des Zones Urbaines Sensibles, 2012).

- 17.

Low-income households: Those whose income is less than the half the median income; see Driant J.-C. and Rieg Ch., “Les ménages à bas revenus et le logement social,” INSEE première n° 962, April 2004

- 18.

Etude sur les refus d’attribution par les demandeurs de logement social. Final Report FORS-Recherche sociale/CREDOC pour l’Union Sociale pour l’Habitat, November 2012, 76 p.

- 19.

The Caisse des dépôts et consignations is an old institution (founded in 1812) aimed at serving as a deposit bank for savings that are then oriented toward social housing construction (preferential loans).

- 20.

The different devices of tax exemption regarding housing received their name from their promoter, generally the Minister of Housing in place. These are more or less “social” according to the government’s political orientations. There was the Périssol in 1996, the Besson in 1999, the de Robien in 2003, and Borloo in 2006. After Scellier in 2009, the current Minister, Cécile Duflot, also proposed a renewed device based on fiscal incentives.

- 21.

See a recent law, the so-called DALO, on “opposable right to housing” (2007), which establishes the responsibility of the State to provide a home to everyone in need and the possibility for an individual to claim this right in court.

- 22.

Baromètre d’image du logement social, TNS SOFRES 2011, http://www.tns-sofres.com/_assets/files/2011.06.08-logement.pdf, consulted 9/2/2013.

- 23.

The 2004–2013 plan envisages the demolition of 139,000 housing units. By the end of 2011, 73,000 housing units had been effectively demolished (93,700 planned) and only 39,7000 had been built (73,000 planned): http://www.ville.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_onzus_2011.pdf, p. 264.

- 24.

See http://www.ville.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_onzus_2011.pdf, pp. 141–165.

- 25.

- 26.

Free author’s translation from French for all USH website quotations.

- 27.

http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Dossier_de_presse_-_logement_socia2012-final.pdf

Consulted 10/2/2013. See also European Parliament, Karima Delli report for the Commission of Employment and Social Affairs (2012/2293(INI). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=−//EP//NONSGML+COMPARL+PE-504.103+01+DOC+PDF+V0//FR&language=EN, consulted 1/2/2013.

- 28.

Expected to be an exemplar of a sustainable city: http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/Lancement-du-label-national,31489.html

- 29.

See GRIDAUH-USH report, “Le partenariat entre les organismes d’HLM et les opérateurs privés,” September 2009

- 30.

Different legal forms of private enterprises, called “civil societies,” and composed of several individual or collective partners.

- 31.

VINCI is a well-known constructor that is active in different markets (mainly transport and construction), more recently in what we call the “social housing market.” http://www.institut-entreprise.fr/fileadmin/Docs_PDF/travaux_reflexions/LLG07Financement/VINCI2presentation.pdf

References

Ball J (2008) Housing disadvantaged people? insiders and outsiders in French social housing. Routledge, Abingdon

Blanc M (2010) The impact of social mix policies in France. Hous Stud 25(2):257–272

Bourgeois C (2012) Quand expertise, normes et délibérations conditionnent l’accès aux droits sociaux : le cas des commissions Droit au logement. In: Bureau M-C, Sainsaulieu I (eds) Les configurations pratiques de l’Etat social. Septentrion, Paris, pp 133–151

Brouant J (2011) Implementation of the enforceable right to housing (DALO) confronted to local practices and powers. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La Documentation Francaise, Paris, pp 278–291

Chevalier C, Lebeaupin F (2010) La population des zones urbaines sensibles. INSEE première n°1328

Czischke D, Gruis V, Mullins D (2012) Conceptualising social enterprise in housing organisation. Hous Stud 27(4):418–437

Données statistiques (2012) http://www.union-habitat.org/sites/default/files/Donn%C3%A9es%20statistiques%202011.pdf. Consulted 4 Jan 2013

Driant J-C (2011) The inertia and metamorphosis at work in France’s social housing sector. the HLM system at the turn of the decade. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La Documentation Francaise, Paris, pp 116–131

Ghekiere L (2008) Le développement du logement social dans l’Union Européenne. Recherches et Prévisions n° 94

Ghékière L (2011) How social housing has shifted its purpose, weathered the crisis and accommodated European Community competition law. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La Documentation Francaise, Paris, pp 135–151

Houard N (2011) A change of direction towards the residualisation of social housing? In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La documentation française, Paris, pp 334–356

Houard N, Lelévrier Ch (2012) Mobilité et choix résidentiels : quels enjeux pour les politiques publiques ?. In: Politique de la ville. Perspectives françaises et ouvertures internationales, Centre d’analyse stratégique, Rapports et document n°52, La documentation française, Paris, pp 99–110

Houard N, Lévy-Vroelant C (2013) The (enforceable) right to housing: a paradoxical French passion (1990–2012). Int J Hous Policy, London, Routledge 13(2):202–214

Jacquot A (2007) L’occupation du parc HLM. Eclairage à partir des enquêtes logement de l’INSEE. Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, document de travail n° F0708

Jaillet M (2011) Mix in French housing policies: a “sensitive” issue”. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La Documentation Francaise, Paris, pp 318–333

Kirszbaum (2011) Social housing in the unthought of the multi-ethnic town. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La Documentation Francaise, Paris, pp 292–217

Lévy J-P, Fijalkow Y (2012) Une autre politique du logement est-elle possible ? Le monde, Tribune, 1.03.2012. http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2012/03/01/une-autre-politique-du-logement-est-elle-possible_1649893_3232.html

Levy-Vroelant C (2010) Housing vulnerable groups: the development of a new public action sector. Eur J Hous Policy 10(4) pp 443–456(14), Routledge

Lévy-Vroelant C (2011) Housing as welfare? Social housing and the welfare state in question. In: Houard (ed) Social housing across Europe. La documentation française, Paris, pp 191–214

Lévy-Vroelant C, Reinprecht C (2013) Housing the poor in Paris and Vienna, the changing understanding of ‘social’. In: Scanlon K, Whitehead C (eds) Social housing in Europe. LSE/Wiley, London (forthcoming)

Levy-Vroelant C, Tutin C (2010a) Le logement social en Europe au début du 21ème siècle : la révision générale. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, France, 247 p

Lévy-Vroelant C, Tutin Ch (2010b) France: un modèle généraliste en question In : Lévy-Vroelant C, Tutin Ch (eds) Le logement social en Europe au début du XXIe siècle, La révision générale. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 247 p

Lévy-Vroelant C, Reinprecht C, Robertson D, Wassenberg F (2013a) Learning from history: ‘Path dependency’ and change in the social housing sectors of Austria, France, the Netherlands and Scotland, 1889-2012. In: Scanlon K, Whitehead C (eds) Social housing in Europe. LSE/Wiley, London (forthcoming)

Lévy-Vroelant C, Schaefer J-P, Tutin C (2013b) Social housing in France. In: Scanlon K, Whitehead C (eds) Social housing in Europe. LSE/Wiley, London (forthcoming)

Lovatt R, Lévy-Vroelant C, Whitehead C (2006) Foyers in the UK and France – comparisons and contrasts. Eur J Hous Policy 6(2):151–166

Mullins D, Czischke D, van Borter G (2012) Exploring the meaning of hybridity and social enterprise in housing organisations. Housing Stud 27(4):405–417, 2012 Special Issue: Social Enterprise, Hybridity and Housing Organisations

Pichon P (2011) Housing policies for the homeless. Or what a closer look at moving off the streets and into a real home shows. In: Houard (ed) La documentation française, Paris, pp 263–277

Pollard J (2010) Soutenir le marché : les nouveaux instruments de la politique du logement. Sociologie du travail, n°52

Sala Pala V (2005) Social housing policy and the construction of ethnic borders. A comparison of France and Great Britain. Political science doctoral thesis, Rennes, Rennes 1 University

Scanlon K, Whitehead C (2013) Social housing in Europe. LSE/Wiley, London (forthcoming)

Wacquant L (2008) Urban outcasts: a comparative sociology of advanced marginality. Polity Press, Cambridge

Zittoun P (2000) Quand la permanence fait le changement. Coalitions et transformations de la politique du logement. Politiques et management public 18(2):123–147

Zittoun P (2009) Understanding policy change as a discursive problem. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract 11(1):65–82

Reports

Droit au logement, rappel à la Loi (2012, November) Comité de suivi du droit au logement opposable, 142 p. http://www.cnle.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/6e_rapport_Dalo_def-1.pdf

Housing policy and vulnerable social groups (2008) Report and guidelines prepared by the Group of Specialists on Housing Policies for Social Cohesion (CS-HO). Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg

Le rôle du logement dans les parcours d’exclusion liée au logement. Logement et exclusion liée au logement, Thème annuel 2008 (2010) Rapport Européen, Feantsa, Thorne European service, 29 p

L’état du mal-logement en France en 2012, 18ème rapport (2013, February) Fondation Abbé Pierre pour le logement des personnes défavorisées (FAP), 242 p. http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/124000639/0000.pdf

Overview of Housing policies. Housing in the EU member states (2006) Directorate General for Research, Working document, Social affairs, series W 14. European Parliament, Brussels

Social Housing Allocation and Homelessness (2011) European observatory of homelessness, EOH comparative studies on homelessness, Feantsa. Pleace N, Teller N, Quilgars D (eds) Brussels, 80 p. http://eohw.horus.be/files/freshstart/Comparative_Studies/2011/Feantsa_Comp_Studies_01_2011_WEB.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lévy-Vroelant, C. (2013). “Everyone Should Be Housed”: The French Generalist Model of Social Housing at Stake. In: Chen, J., Stephens, M., Man, Y. (eds) The Future of Public Housing. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41622-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41622-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-41621-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-41622-4

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)