Abstract

Promoting participation in productive activities after labour market exit is an important challenge for European policies. Not only society as a whole might profit from an increased investment, but also older people themselves, since participation in a productive activity, such as voluntary work, was shown to improve health and well-being in older ages (Bath and Deeg 2005) – a finding that was also found in the two first waves of SHARE (Siegrist and Wahrendorf 2009a). These results suggest that being engaged in a productive activity after labour market exit helps to cope with the ageing process because valued earlier activities are replaced by new ones, providing opportunities of positive self-experience which in turn strengthens well-being and health. Previous findings, though, show that participation varies considerably according to social position and between different countries (see also Hank 2010).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Labour Market

- Voluntary Work

- Labour Market Policy

- Psychosocial Work Environment

- Psychosocial Working Condition

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Social Position and Participation Across European Countries

Promoting participation in productive activities after labour market exit is an important challenge for European policies. Not only society as a whole might profit from an increased investment, but also older people themselves, since participation in a productive activity, such as voluntary work, was shown to improve health and well-being in older ages (Bath and Deeg 2005) – a finding that was also found in the two first waves of SHARE (Siegrist and Wahrendorf 2009a). These results suggest that being engaged in a productive activity after labour market exit helps to cope with the ageing process because valued earlier activities are replaced by new ones, providing opportunities of positive self-experience which in turn strengthens well-being and health. Previous findings, though, show that participation varies considerably according to social position and between different countries (see also Hank 2010).

Higher participation rates were particularly observed among people with higher education and higher income. Whereas the descriptive evidence of this social gradient of participation is convincing, the explanations given so far are limited and still need to be explored. In particular, the relative contribution of earlier stages in the life course in explaining these variations, such as working conditions in mid-life, remains an open challenge. But why – or how – should former working conditions exactly be related to participation in productive activities after labour market exit?

One reason might be that the motivation of getting active is higher, given that positive work-related experience occurred. In other words, people in low social position might experience poor working conditions in terms of exposure to psychosocial stress at work. As a result, the intention to retire is higher (Siegrist and Wahrendorf 2009b), and leaving the labour market is probably not experienced as such a remarkable “role loss”, which needs to be compensated, but rather as a relief from the obligations of employment (Westerlund et al. 2009). As a consequence, people in low social position are probably less willing to engage in such an activity after labour market exit. Another reason might be that “good” working conditions in midlife contribute to increased health at older age, which in turn favours the participation in productive activities after labour market exit. Along these lines, several longitudinal investigations demonstrate that former working conditions exert long-lasting effects on health and well-being (Blane 2006). But long lasting influences on participation in productive activities still need to be explored.

In addition to variations according to social position, former SHARE-findings also show that participation rates differ between countries, in particular in case of volunteering (Hank 2010; Siegrist and Wahrendorf 2009a). While rates of volunteering were found to be high in the Northern countries together with the Netherlands, Belgium and France, rates were rather low in Italy, Spain and Greece and the two Eastern countries. So far, these findings are generally discussed in the frame of tailored policy programs which may encourage participation in productive activity (Hank 2010; Salomon and Sokolowski 2003). But which policy programs are these exactly? Can this probably also be related to country-specific labour market policies that increase working conditions in mid-life (e.g. rehabilitative services). Recent findings based on the SHARE study show clear country-variations of quality of work according to such factors (Dragano et al. 2010). But can these factors also be related to participation after labour market exit?

Taken together, the complex associations between policy measures, working conditions in mid-life and participation in productive activities remain as an open challenge and have not been explored so far. One reason is that former investigations are mainly based on cross-sectional findings, with no available information from former stage in the life course. With its broad set of retrospective life history information from respondents in 13 Continental European countries, SHARELIFE offers unique opportunities to relate former life stages with participation after labour market exit, and to give initial answers to the addressed questions above. More specifically, three questions will be explored.

-

1.

Are working conditions in mid-life associated with participation in productive activities after labour market exit?

-

2.

If so, to what degree can this association be explained by better health after labour market exit?

-

3.

Which macro factors are related to higher participation rate and might help to increase participation in productive activities in older ages?

To study these questions, we focus on volunteering as an important type of productive activity, and we analyse working conditions, in terms of different aspects of respondents’ work history (see Measurement section), including the exposure to psychosocial stress at work during the working career – all information taken from the retrospective data collection in SHARELIFE.

2 Measuring Working Conditions in Mid-life in Relation to the Welfare State

For our analyses we combined the information from the SHARELIFE survey, with information from the second wave of SHARE, where participation in volunteering was assessed. Since we were interested in participation in voluntary work after labour market exit, we restricted the sample to people aged 50 or older who already left the labour market at wave 2. Moreover, if the interviewer reported any difficulties of the respondent to answer the questions in the retrospective questionnaire, respondents were excluded (4% of the cases). This restriction results in a sample of 14,150 respondents. Weights were considered within the analyses.

SHARELIFE includes an extensive module on work history. This module allows us to reproduce the respondents’ principal occupational situation from the age of 15 onwards, by collecting information on each job together with details on periods where the respondent was not employed (if the respective period lasted 6 months or longer). Information on jobs includes a measure of occupational status (based on ISCO codes), information on working time (full-time or part-time), and information on the psychosocial work environment (for the last main job of the working career). Information on existing gaps includes a description of the situation (e.g. unemployed, sick or disabled, domestic work, etc.). On this basis, we created a variable describing the respective employment situation for each age between 15 and 65 (or age at the SHARELIFE interview if respondent younger than 65) using seven different categories. The categories and their prevalence by age are displayed in Fig. 16.1 separately for men and women for the total SHARELIFE sample.

For the following analyses, six variables were created to describe specific characteristics of respondents’ work history based on the collected information: (1) a binary indicator describing whether the respondent experienced an episode of unemployment in working life, (2) years since labour market exit, (3) a variable indicating whether an episode of being sick and disabled occurred during working life, (4) the average number of job changes in the working life. Moreover, we created a variable measuring (5) the occupational status of the main job of the working career. The categories are “Legislators and professionals”, “Associated professionals and clerks”, “skilled workers”, and “elementary occupations”. And lastly, to measure adverse psychosocial working conditions, we created (6) five binary indicators measuring core dimensions of work stress – again for the main job of the working career. Those indicators are based on 12 questionnaire items (four-point Likert scaled) referring to existing questionnaires (Karasek et al. 1998; Siegrist et al. 2004). The assessed dimensions are physical demands (two items), psychosocial demands (three items), social support at work (three items), control at work (two items), and reward (two items). For the analyses, we calculated a simple sum-score for each dimension with higher scores indicating higher work stress and created a binary indicator, where participants scoring in the upper tertiles of the respective measure were considered experiencing poor quality of work.

Rather than using existing welfare state typologies for our analyses, we choose specific macro indicators of welfare state interventions of a country, both related to the labour market policy of a country: (1) extent of lifelong learning, and (2) amount of expenditure in rehabilitative care. Life long learning is a key concept to promote decent employment at all ages. Especially the older workforce profits from continuous education as it improves their level of qualification and therefore their position in the labour market. The variable refers to persons aged 25–64 who stated that they received education or training in the 4 weeks preceding the EU Labour Force Survey. Information on expenditure in rehabilitation service is taken from the Eurostat database on labour market policy. It refers to the labour market policy expenditures that are invested in supported employment and rehabilitation services, measured as percentage of GDP. For both macro-variables, we used the mean value based on the available information since 1985. Both aspects are thought to be related to “good” working conditions – life long learning, since it improves the level of qualification and increases personal control at work and opportunities in the labour market, and rehabilitative care, since it influences the probability and time interval of returning to work by increasing the health status during working life.

As mentioned above, participation in voluntary work was used as our main outcome variable, which was measured in wave 2 of the SHARE project. More specifically, respondents were asked whether or not they were involved during the last 4 weeks in “voluntary or charity work”.

Additional variables are gender, age (divided into age categories), education (low, medium, high) as well as two health indicators taken from wave 2: one binary indicator for functional limitation (either ADL or IADL limitations) and poor self-perceived health (less than good on a five–likert scale ranging from excellent to poor).

3 Associations of Working Conditions and Volunteering After Labour Market Exit

How are working conditions related to participation in volunteering? Table 16.1 gives an initial answer to this question, by showing the participation rates according to all covariates under study. But before turning to working conditions, we first observe that participation varies according to gender (more men), age (higher rates between age 60 and 80), and education (higher rates among higher educated). Furthermore, both health indicators are associated with increased participation rates. With regard to working conditions the results suggest that participation rates are higher among people who had a higher occupational status in working life, who experienced frequent job changes in their, and among those who experienced no episode of unemployment or of being sick and disabled.

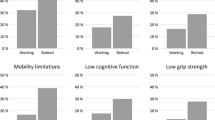

When turning to the indicators of psychosocial work conditions, we observe for all five indicators that people who experienced poor working conditions in their main job are less likely to participate in voluntary work once they left the labour market. This holds particularly true in case of high physical demands, low work control, low reward at work and in case of low social support at work. Results of Table 16.1 are consistent at the country level – as exemplified for social position (Fig. 16.2) and for low control and low reward (Fig. 16.3).

But to what extent can these associations be explained by increased health in older ages? To answer this question (our second research question) we additionally present results of multivariate analyses in Table 16.2, where the effect is estimated for each working condition – before (model 1) and after adjustment for the two health indicators under study (model 2). When turning to model 1 (first column), we observe that findings of the descriptive analyses remain stable. Again, people with a higher occupational status in their working career are more likely to participate in volunteering during retirement, as well as people who experienced no period of unemployment, or with frequent job changes. Furthermore, four of the five work stress indicators are found to be significantly associated to volunteering during retirement, namely high physical demands, low work control, low reward at work and low social support at work. Importantly all these reported associations are only modestly reduced when adjusting for health after labour market exit in model 2, and these associations remain significant. This result suggests that the experience of poor working conditions in midlife reduces the probability of volunteering during retirement independent of participants’ health status.

Next, we explore how the two macro indicators are related to country-rates of participation. Results are displayed in Fig. 16.4. We observe that participation rates are generally lower in countries with lower rates of life long learning and in countries that invest less in occupational rehabilitative services.

4 Summary

With this contribution we set out to study the long lasting influences of working conditions in mid-life on participation in voluntary work after labour market exit using information on respondents’ work history collected in the SHARELIFE interview to identify specific working conditions in mid-life. By doing so, we were particularly interested in studying the relative contribution of an adverse psychosocial work environment on the probability of participation. Moreover, we studied the question to what extent this association can be explained by decreased health status during retirement. Finally, we explored the relation between specific macro indicators which are thought to affect active engagement of retired people (by improving work and employment in midlife) and likelihood of participating in volunteering. Results can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Our findings emphasize that people who experienced poor working conditions in midlife are less likely to engage in volunteering after labour market exit. This holds true for people who experienced an episode of unemployment, who were holding a low status job, and who had few job changes. Moreover, poor psychosocial working conditions were associated with low participation rates, specifically work and employment conditions defined by high physical demands, low control, low reward, and low social support.

-

2.

These reported associations remain significant after adjusting for health status (functional limitations and self-perceived health). Apparently, working conditions seem to have long-lasting effects on the probability of participating in productive activities after labour market exit – effects that are not substantially reduced by people’s health status.

-

3.

The extent of volunteering in early old age is also influenced by a nation’s investments into macro-structural policy measures that aim at improving quality of work and employment. Our results demonstrate this effect for two such indicators, the extent of lifelong learning, and the amount of resources spent in rehabilitation services. In either case, country’s overall rates of participation in volunteering were clearly higher compared to countries with fewer investments.

Our results show that SHARELIFE offers promising opportunities to study life course influences on participation in productive activities after labour market exit, focussing on working conditions over the life course. Previous investments in voluntary work during working life (beside work) might be another important predictor (Erlinghagen 2010). Yet, since we focussed on respondents’ principal occupational situation over the life course, this information was not included. Despite this possible shortcoming, the findings suggest that promoting working conditions in midlife might not only increase health and well-being, but also encourage participation in productive activities after labour market exit.

References

Bath, P. A., & Deeg, D. (2005). Social engagement and health outcomes among older people: Introduction to a special section. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 24–30.

Blane, D. (2006). The life course, the social gradient, and health. In M. Marmot & R. Wilkinson (Eds.), Social determinants of health (pp. 54–77). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dragano, N., Siegrist, J., & M. Wahrendorf, (2010). Welfare regimes, labour policies and workers’ health: A comparative study with 9917 older employees from 12 European countries. JECH, in press.

Erlinghagen, M. (2010). Volunteering after retirement. Evidence from German panel data. European Societies, 12(5), 603–625.

Hank, K. (2010). Societal determinants of productive aging: A multilevel analysis across 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, in press.

Karasek, R., Brisson, C., Kawakami, N., Houtman, I., Bongers, P., & Amick, B. (1998). The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 322–355.

Salomon, L. M., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2003). Institutional roots of volunteering: Towards a macro-structural theory of individual voluntary action. In L. Halman & P. Dekker (Eds.), The values of volunteering (pp. 71–90). New York: Kluwer Academic.

Siegrist, J., Starke, D., Chandola, T., Godin, I., Marmot, M., & Niedhammer, I. (2004). The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1483–1499.

Siegrist, J., & Wahrendorf, M. (2009a). Participation in socially productive activities and quality of life in early old age: Findings from SHARE. Journal of European Social Policy, 19, 317–326.

Siegrist, J., & Wahrendorf, M. (2009b). Quality of work, health, and retirement. The Lancet, 374, 1872–1873.

Westerlund, H., Kivimäki, M., Singh-Manoux, A., Melchior, M., Ferrie, J., & Pentti, J. (2009). Self-rated health before and after retirement in France (GAZEL): A cohort study. The Lancet, 374, 1889–1896.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wahrendorf, M., Siegrist, J. (2011). Working Conditions in Mid‐life and Participation in Voluntary Work After Labour Market Exit. In: Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hank, K., Schröder, M. (eds) The Individual and the Welfare State. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17472-8_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17472-8_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-17471-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-17472-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)