Abstract

Increasingly, studies have shown that grandiose narcissism can be adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive narcissism (characterized by authority and self-sufficiency) and maladaptive narcissism (characterized by exploitativeness, entitlement, and exhibitionism) differ in their associations with the Big Five personality traits, inter- and intrapersonal adaptions, and problem behaviors and differ in their developmental trajectories and genetic and environmental foundations. Supportive evidence includes (1) high maladaptive narcissism tended to be associated with high neuroticism, actual-ideal discrepancies, depression, anxiety, aggression, impulsive buying, and delinquency but associated with low empathy and self-esteem, whereas high adaptive narcissism tended to manifest null or opposite associations with those variables; (2) maladaptive narcissism declined with age, whereas adaptive narcissism did not; (3) adaptive and maladaptive narcissism differed substantially in their genetic and environmental bases. These findings deepen our understanding about grandiose narcissism and gandiose narcissists and suggest the importance of distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism in future research and intervention practice.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In most people’s eyes, narcissists are arrogant, selfish, exploitive, entitled, and aggressive. In a word, narcissism is “…‘bad’ and predicts other ‘bad’ things” (Campbell & Foster, 2007, p. 116; Lasch, 1979). Indeed, narcissism has been treated as a pathological disorder ever since its introduction into psychology (Ellis, 1898; Freud, 1914/1957; Kernberg, 1975; Kohut, 1977). Yet, decades of research on narcissism in normal populations has suggested that to some extent and in some aspects, narcissism could also be desirable and adaptive (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2010; Sedikides, Rudich, Gregg, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2004; Watson & Biderman, 1993). For example, narcissists tend to be confident, assertive, extraverted, energetic, and happy (Watson & Biderman, 1993), and they are more likely to have high self-esteem and less likely to experience depression and anxiety (Sedikides et al., 2004). Conscious of both the pros and cons associated with narcissism, researchers recently have attempted to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism and study them separately (Barry, Frick, Adler, & Grafeman, 2007; Hepper, Hart, & Sedikides, 2014; Hill & Yousey, 1998).

In this chapter, we elaborate on evidence that supports a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism and discusses the implications therein. In doing so, we focus on narcissism in the normal population (i.e., not the clinical disorder) and a specific variant known as “grandiose narcissism ” (in contrast to “vulnerable narcissism”). Grandiose narcissism is characterized by an inflated self-view, agentic orientation, selfishness, and a sense of specialness (Campbell & Foster, 2007).

Distinction Reflected in the Research Tradition

Exploration about narcissism has followed two traditions: clinically based and personality-based . While clinical psychologists have long treated narcissism as a pathological disorder that concerns clinical populations (Kernberg, 1975; Kohut, 1977; Pincus, Cain, & Wright, 2014), personality psychologists have largely considered it as a medley of adaptive and maladaptive components that are observed in normal populations (Raskin & Terry, 1988; Emmons, 1987). Almost from the nascence of the personality tradition, researchers have proposed two types of narcissism (Emmons, 1984; Watson & Biderman, 1993). One type is maladaptive, echoing the clinical tradition to some extent and encompassing defensiveness, aggressiveness, and egotism (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998). The other type is adaptive, reflecting the healthy components of narcissism and characterized by successful self-exhibition, acceptable self-aggrandizement, and high confidence (Kernberg, 1975; Watson & Biderman, 1993). Consistent with this proposal, decades of research has yielded a large body of evidence supporting a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism.

Distinction Reflected in the Measure of Narcissism

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI, Raskin & Hall, 1979) has served as the primary measure of grandiose narcissism. NPI scores , moreover, are often the basis of conceptualizations of grandiose narcissism (Cain, Pincus, & Ansell, 2008). The NPI was developed in conjunction with descriptions of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III ; American Psychiatric Association, 1980). The scale originally included 220 items, mostly tapping grandiose expressions of pathological narcissism, and eventually was refined and reduced to 40 items (Raskin & Hall, 1979; Raskin & Terry, 1988). Factor analyses have revealed diverse factor structures underlying the NPI, with factors of 2 (Power and Exhibitionism, Kubarych, Deary, & Austin, 2004; Leadership/Authority and Exhibitionism/Entitlement, Corry, Merritt, Mrug, & Pamp, 2008), 3 (Power, Exhibitionism, and Specialness, Kubarych et al., 2004; Leadership/Authority, Grandiose/Exhibitionism, and Entitlement/Exploitativeness, Ackerman et al., 2011), 4 (Exploitativeness/Entitlement, Leadership/Authority, Superiority/Arrogance, and Self-Absorption/Self-Admiration, Emmons, 1984, 1987), and 7 (Authority, Self-Sufficiency, Superiority, Exhibitionism, Exploitativeness, Vanity, and Entitlement, Raskin & Terry, 1988).

Despite the complexity and inconclusiveness of the factors underlying the NPI, researchers have observed that the NPI includes both healthy and unhealthy factors (e.g., Emmons, 1984; Raskin & Terry, 1988). This distinction is most evident in the seven-factor model: authority and self-sufficiency are healthy and associated with such desirable traits as self-confidence and assertiveness , whereas entitlement, exploitativeness, and exhibitionism are unhealthy and associated with poor psychological well-being and social adjustment (Raskin & Terry, 1988; Watson & Biderman, 1993). Using these factors, researchers have developed two NPI subscales that gauge adaptive and maladaptive narcissism separately (Barry, Frick, & Killian, 2003). The two subscales have exhibited acceptable reliability (i.e., internal consistency) and validity (i.e., predictive validity and construct validity) (Barry et al., 2007; Cai, Shi, Fang, & Luo, 2015; Hepper et al., 2014). Most evidence we review in the sections below employs this measurement scheme.

Distinction Reflected in Personality Nomologic Networks

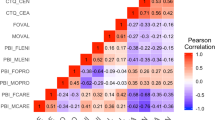

Research on overall grandiose narcissism has established that it is positively correlated with extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness but negatively with neuroticism and agreeableness (for a review, Miller & Maples, 2011), with the magnitude of the correlations varying from small for conscientiousness (0.08) to moderate for extraversion (0.39). Research based on factors of grandiose narcissism has consistently demonstrated that all factors, whether they be healthy or unhealthy, are positively correlated with extraversion and negatively with agreeableness. The healthy and unhealthy factors differ, however, in their relationship with neuroticism, while relatively healthy factors, such as leadership and authority , are negatively associated with neuroticism; relatively unhealthy factors such as entitlement and exploitativeness are positively associated with it (Ackerman et al., 2011; Brown, Budzek, & Tamborski, 2009; Corry et al., 2008; Hill & Roberts, 2012). Thus, although healthy and unhealthy factors share some similarities in terms of a nomologic foundation for personality, they differ in their associations with neuroticism .

Distinction Reflected in Associations with Intrapersonal Adaptions

Research has revealed that healthy and unhealthy components of grandiose narcissism manifest distinct associations with intrapersonal adaptions. Individuals with higher scores for exploitativeness or entitlement are more likely to be self-conscious (Watson & Biderman, 1993), to report larger actual-ideal discrepancies (Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995), and to possess lower self-esteem (Brown et al., 2009). Higher levels of exploitativeness or entitlement have been linked to increased mood variability and emotional intensity (Emmons, 1987), greater neuroticism (Emmons, 1984), and higher scores on the Narcissistic Personality Disorder scale (Emmons, 1987; Watson, Grisham, Trotter, & Biderman, 1984). In contrast, individuals who score higher on the Leadership/Authority dimension report a higher level of self-awareness (Watson & Biderman, 1993) and self-esteem (Brown et al., 2009; Emmons, 1984; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995; Watson & Biderman, 1993; Watson, Little, Sawrie, & Biderman, 1992) and a lower level of neuroticism (Emmons, 1984; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995) and actual-ideal self-discrepancy (Emmons, 1984; Raskin & Terry, 1988; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995). Furthermore, Leadership/Authority is negatively associated with indices of poor psychological well-being, such as anxiety, social anxiety, depression, and personal distress (Emmons, 1984; Watson & Biderman, 1993; Watson & Morris, 1991). Taken together, adaptive and maladaptive components of narcissism are associated with intrapersonal adaptions in opposite directions: while the former is beneficial, the latter is detrimental.

Distinction Reflected in Associations with Interpersonal Adaptions

Grandiose narcissism can be toxic in interpersonal situations. Not all components of grandiose narcissism, however, are problematic. Two lines of evidence are available so far. The first line of evidence involves the relationship between narcissism and aggression. It is well-known that people with high grandiose narcissism are often high in aggression. When confronted with failure, social rejection, or any other source of threat to the ego, they often respond in aggressive ways (Baumeister, Bushman, & Campbell, 2000; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). For instance, they may denigrate evaluators, punish competitors, and even act antagonistically toward innocent others (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Horton & Sedikides, 2009; Martinez, Zeichner, Reidy, & Miller, 2008; Twenge & Campbell, 2003). Exploration of the relationship between aggressiveness and specific components of narcissism, however, have shown that aggressiveness is mainly associated with unhealthy components such as entitlement and exploitativeness rather than the relatively healthy self-sufficiency and superiority components (Moeller, Crocker, & Bushaman, 2009; Reidy, Zeichner, Foster, & Martinez, 2008; Washburn, McMahon, King, Reinecke, & Silver, 2004; but see Blinkhorn, Lyons, & Almond, 2015).

A second line of evidence has examined the relationship between grandiose narcissism and empathy . Overall, research has shown that high grandiose narcissism is associated with low empathy (Fan et al., 2011; Watson et al., 1984). For specific components of narcissism, however, research shows that lack of empathy is more likely to be associated with unhealthy components rather than the healthy ones. An early study examined the relationship between empathy and the various factors underlying the NPI (Watson & Morris, 1991). Results showed that exploitativeness/entitlement was negatively associated with empathic concern and perspective taking but others factors were not. Later, a study examined adaptive and maladaptive narcissism among adolescents directly and found that maladaptive narcissism was related to a constellation of callous-unemotional traits (e.g., failure to show empathy, constricted display of emotion), whereas adaptive narcissism was not (Barry et al., 2003). More recently, a series of studies examined how adaptive and maladaptive narcissism were differentially associated with state empathy (Hepper et al., 2014). Results showed that when exposed to a target person’s distress, individuals high in maladaptive narcissism (as opposed to those high in adaptive narcissism) displayed low momentary empathy as indicated by both self-reports (Study 1) and autonomic arousal (Study 3). Taken together, it is maladaptive narcissism rather than adaptive narcissism that is associated with interpersonal problems.

Distinction Reflected in Associations with Problem Behaviors

Two kinds of problem behaviors have been shown to be differentially associated with adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. One has to do with impulsive buying. Grandiose narcissism has been linked to problematic consumption behaviors (Rose, 2007). One of our recent studies, however, showed that it is maladaptive narcissism rather than adaptive narcissism that predicts a tendency of impulsive buying (Cai et al., 2015). In this research, we first demonstrated with an internet sample that impulsive buying is positively associated with maladaptive narcissism but not with adaptive narcissism (Study 1). We then replicated this finding with a twin sample and further showed that the association between maladaptive narcissism and impulsive buying had a genetic foundation (Study 2).

Another involves conduct in children and adolescence (Barry et al., 2003; Washburn et al., 2004). A longitudinal study investigated a group of children and young adolescents over a 4-year period (Barry et al., 2007). Results showed that while maladaptive narcissism predicted delinquency and police contact at all follow-ups, adaptive narcissism exhibited no significant correlation with delinquency and a significantly negative one with police contact. In summary, it is maladaptive narcissism but not adaptive narcissism that predicts problem behaviors.

Distinction Reflected in Developmental Trajectories

Only a few studies have examined the development of narcissism. A longitudinal study showed that in general, observer-rated narcissism increased from ages 14 to 18, followed by a slight but nonsignificant decline from ages 18 to 23 (Carlson & Gjerde, 2009); multiple cross-sectional studies have shown that narcissism is negatively correlated with age in adulthood (Foster, Campbell, & Twenge, 2003; Roberts, Edmonds, & Grijalva, 2010). These studies suggest that narcissism increases during adolescence but tends to decline during adulthood. Interestingly, Foster et al. (2003) also demonstrated that age-related decreases tend to be larger for the maladaptive components (i.e., exhibitionism, exploitativeness, and entitlement) than for the adaptive components (i.e., self-sufficiency and authority). A recent large cross-sectional study has investigated more than 20,000 people in China (Cai, Kwan, & Sedikides, 2012). This study, again, replicated the age-related downward trend for overall grandiose narcissism. It demonstrated, moreover, differential trajectories for adaptive and maladaptive narcissism: while adaptive narcissism remained stable across a life-span, maladaptive narcissism exhibited a decreasing tendency.Footnote 1 Together, these findings indicate that adaptive and maladaptive aspects of narcissism follow different developmental trajectories.

Distinction Reflected in Genetic and Environmental Bases

Two previous studies have examined grandiose narcissism from the perspective of behavioral genetics. Overall, substantial genetic influences on grandiose narcissism have been found in both Asian and Western samples (e.g., Luo, Cai, Sedikides, & Song, 2014; Vernon, Villani, Vickers, & Harris, 2008). Furthermore, non-shared environments (i.e., environments not shared by twin siblings, like life events), but not shared environments (i.e., environments shared by twin siblings, like living conditions), exhibited a pronounced influence on narcissism. Two recent twin studies shed light on how these effects might vary with whether grandiose narcissism is adaptive or maladaptive. One examined the etiology of grandiosity and entitlement, which are reflective of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism, respectively (Luo, Cai, & Song, 2014). These results showed that the genetic and environmental effects on grandiosity and entitlement were largely different: less than 10% of genetic and environmental effect were accounted for by common genetic and environmental factors. The other twin study examined adaptive and maladaptive narcissism directly. Results revealed that both aspects were heritable, with more than half of their variation accounted for by unique environments (Cai et al., 2015); more importantly, the majority of the genes (54%) and environments (85%) underlying adaptive and maladaptive narcissism were different.Footnote 2 These two studies provide both direct and indirect evidence for the distinct genetic and environmental foundations of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism.

Conclusions, Implications, and Future Directions

To date, studies on grandiose narcissism have focused primarily on overall narcissism and relied on the NPI for analysis. In this chapter, we illustrated evidence indicating that grandiose narcissism actually includes two distinct components: adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. Based on the seven-factor model of the NPI (Raskin & Terry, 1988), research has established that while exhibitionism, entitlement, and exploitativeness are maladaptive, authority and self-sufficiency are adaptive (with superiority and vanity being neither adaptive nor maladaptive). Adaptive and maladaptive narcissism differ from each other in terms of how they correlate with other personality traits, inter- and intrapersonal adaptions, problem behaviors, developmental trajectories, and genetic and environmental foundations. People with high maladaptive narcissism are more likely to score higher in neuroticism, actual-ideal discrepancies, depression, anxiety, aggression, impulsive buying, and delinquency but lower in empathy and self-esteem. In contrast, people with high adaptive narcissism are more likely to manifest the opposite tendencies for almost every one of these traits and proclivities. Moreover, maladaptive narcissism declines with age, whereas adaptive narcissism does not. Particularly notable, adaptive and maladaptive narcissism differ substantially in their genetic and environmental bases. These findings provide convergent and consistent evidence for the distinctiveness between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism as well as the double-edged sword nature of grandiose narcissism.

Distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism may help us better understand the complexity of grandiose narcissism as well as other relevant findings. First, we may gain a more nuanced understanding about grandiose narcissism and grandiose narcissists. People with extremely high grandiose narcissism must be high in both adaptive and maladaptive facets, that is, attractive but toxic; people with moderate narcissism may be high in either facet or moderate in both facets, that is, proud but not too annoying, annoying but not too proud, or somewhat proud and somewhat annoying; a low narcissist should be low in both facets, thus behaving in a modest and agreeable manner. These possibilities suggest that narcissists with similar scores on the NPI still may be quite different from each other. Second, we may have a better understanding about the mixed nature of the NPI and further its ambiguous correlations with many other constructs. Although the NPI’s latent factor structure is still inconclusive, as the chief measure of narcissism (although see Chap. 12 by Foster et al., this volume, for a review of additional measures of grandiose narcissism), two functionally distinct components emerge: adaptive and maladaptive. These two components may have correlations with other variables differing in magnitude (e.g., correlations with impulsive buying, Cai et al., 2015) or direction (e.g., correlations with neuroticism Ackerman et al., 2011; Corry et al., 2008). As a result, correlations based on the total score of the NPI are possibly confounded and may be misleading at times. These possibilities suggest that we should be cautious whenever we use the total score of the NPI as an index of grandiose narcissism and examining its relationship with other variables.

Evidence for the distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism also suggests future directions for both empirical research and intervention practice. First, most studies on narcissism so far treat it as a singular construct. Given the distinct nature of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism, studies distinguishing between them are needed, particularly in cases where different results are expected to exist. For instance, research has suggested several contrasting self-regulation strategies employed by narcissists, including inter- versus intrapersonal processes (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001), admiration versus rivalry approaches (Back et al., 2013), and primitive versus mature strategies (Roche, Pincus, Lukowitsky, Menard, & Conroy, 2013). Future study may examine how adaptive and maladaptive narcissism are differentially associated with these self-regulation strategies. Second, since current conceptualizations and operationalizations of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism are based almost exclusively on reformulations of the NPI, future studies should develop purpose-built measures of these two forms of narcissism. Third, since the dark side of narcissism mainly involves its maladaptive component, future intervention practices should treat adaptive and maladaptive narcissism independently and focus on how to curtail the maladaptive aspect while perhaps leaving the adaptive aspect intact (e.g., Hepper et al., 2014).

References

Ackerman, R. A., Witt, E. A., Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., & Kashy, D. A. (2011). What does the narcissistic personality inventory really measure? Assessment, 18, 67–87.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Back, M. D., Kufner, A. C., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034431

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2010). Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism-popularity link at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016338

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., Adler, K. K., & Grafeman, S. J. (2007). The predictive utility of narcissism among children and adolescents: Evidence for a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(4), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9102-5

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., & Killian, A. L. (2003). The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1207/15374420360533130

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(1), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00053

Blinkhorn, V., Lyons, M., & Almond, L. (2015). The ultimate femme fatale? Narcissism predicts serious and aggressive sexually coercive behaviour in females. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.001

Brown, R. P., Budzek, K., & Tamborski, M. (2009). On the meaning and measure of narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(7), 951–964.

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219

Cai, H., Kwan, V. S. Y., & Sedikides, C. (2012). A sociocultural approach to narcissism: The case of modern China. European Journal of Personality, 26, 529–535.

Cai, H., Shi, Y., Fang, X., & Luo, Y. L. L. (2015). Narcissism predicts impulsive buying: Phenotypic and genetic evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 881. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00881

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. J. Spencer (Eds.), The self (pp. 115–138). New York: Psychology Press.

Carlson, K. S., & Gjerde, P. F. (2009). Preschool personality antecedents of narcissism in adolescence and young adulthood: A 20-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(4), 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.003

Corry, N., Merritt, R. D., Mrug, S., & Pamp, B. (2008). The factor structure of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90, 593–600.

Ellis, H. (1898). Auto-eroticism: A psychological study. Alienist and Neurologist, 19, 260–299.

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291–300.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11–17.

Fan, Y., Wonneberger, C., Enzi, B., de Greck, M., Ulrich, C., Tempelmann, C., et al (2011). The narcissistic self and its psychological and neural correlates: An exploratory fMRI study. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1641–1650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171000228x

Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6

Freud, S. (1957). On narcissism: An introduction. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 73–102) (trans: Strachey, J.). London: Hogarth Press.

Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Moving narcissus: Can narcissists be empathic? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1079–1091.

Hill, P., & Roberts, B. W. (2012). Narcissism, well-being, and observer-rated personality across the lifespan. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 216–225.

Hill, R. W., & Yousey, G. P. (1998). Adaptive and maladaptive narcissism among university faculty, clergy, politicians, and librarians. Current Psychology, 17(2/3), 163–169.

Horton, R. S., & Sedikides, C. (2009). Narcissistic responding to ego threat: When the status of the evaluator matters. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1493–1526.

Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson.

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of self. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Kubarych, T. S., Deary, I. J., & Austin, E. J. (2004). The narcissistic personality inventory: Factor structure in a non-clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(4), 857–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00158-2

Lasch, C. (1979). The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. New York: Norton.

Luo, Y. L. L., Cai, H. J., Sedikides, C., & Song, H. R. (2014). Distinguishing communal narcissism from agentic narcissism: A behavior genetics analysis on the agency-communion model of narcissism. Journal of Research in Personality, 49, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.01.001

Luo, Y. L. L., Cai, H. J., & Song, H. R. (2014). A behavioral genetic study of intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions of narcissism. PLoS One, 9(4), e93403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093403

Martinez, M. A., Zeichner, A., Reidy, D. E., & Miller, J. D. (2008). Narcissism and displaced aggression: Effects of positive, negative, and delayed feedback. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.012

Miller, J. D., & Maples, J. (2011). Trait personality models of narcissistic personality disorder, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 71–88). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Moeller, S. J., Crocker, J., & Bushman, B. J. (2009). Creating hostility and conflict: Effects of entitlement and self-image goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(2), 448–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.11.005

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 177–196.

Pincus, A. L., Cain, N. M., & Wright, A. G. (2014). Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in psychotherapy. Personality Disorders-Theory Research and Treatment, 5(4), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000031

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45, 590.

Raskin, R. N., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890–902.

Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., Foster, J. D., & Martinez, M. A. (2008). Effects of narcissistic entitlement and exploitativeness on human physical aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(4), 865–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.015

Rhodewalt, F., & Morf, C. C. (1995). Self and interpersonal correlates of the narcissistic personality inventory: A review and new findings. Journal of Research in Personality, 29, 1–23.

Roberts, B. W., Edmonds, G., & Grijalva, E. (2010). It is developmental me, not generation me: Developmental changes are more important than generational changes in narcissism-commentary on Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691609357019

Roche, M. J., Pincus, A. L., Lukowitsky, M. R., Menard, K. S., & Conroy, D. E. (2013). An integrative approach to the assessment of narcissism. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.770400

Rose, P. (2007). Mediators of the association between narcissism and compulsive buying: The roles of materialism and impulse control. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(4), 576–581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.576

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy? Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2003). “Isn’t it fun to get the respect that we’re going to deserve?” Narcissism, social rejection, and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(2), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202239051

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Vickers, L. C., & Harris, J. A. (2008). A behavioral genetic investigation of the dark triad and the big 5. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(2), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.007

Washburn, J. J., McMahon, S. D., King, C. A., Reinecke, M. A., & Silver, C. (2004). Narcissistic features in young adolescents: Relations to aggression and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 247–260.

Watson, P., & Biderman, M. D. (1993). Narcissistic personality inventory factors, splitting, and self-consciousness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 41–57.

Watson, P. J., Grisham, S. O., Trotter, M. V., & Biderman, M. D. (1984). Narcissism and empathy: Validity evidence for the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_12

Watson, P. J., & Morris, R. J. (1991). Narcissism, empathy, and social desirability. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 575–579.

Watson, P. J., Little, T., Sawrie, S. M., & Biderman, M. (1992). Measures of the Narcissistic Personality: Complexity of Relationships With Self-Esteem and Empathy. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1992.6.4.434

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (17ZDA324) awarded to Huajian Cai. We thank the editors for their insightful comments on an earlier draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cai, H., Luo, Y.L.L. (2018). Distinguishing Between Adaptive and Maladaptive Narcissism. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)