Abstract

In this chapter, we highlight and review the most frequently cited articles that have influenced family business research between 2006 and 2013 from the five most commonly adopted theoretical perspectives: agency theory, resource-based view, stewardship theory, socioemotional wealth, and institutional theory. Using citation counts from Google Scholar, we identified 21 articles that covered these perspectives. Our review discusses the contributions of these highly cited articles, particularly in terms of understanding family firm heterogeneity. We conclude the chapter by suggesting future research directions using these and other theoretical perspectives.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Since 2010, more than 800 peer-reviewed articles on family business research have been added annually to ABI Inform. This research volume indicates an explosive growth of scholarly interest in the field of family business. Albeit a welcome development, this growth presents a challenge for scholars in keeping up with theoretical and empirical progress in the field. In order to make sense of the growing literature, family business scholars have paused from time to time to take stock of what we know or do not know, consolidate knowledge, and identify future research directions (e.g., De Massis et al. 2013; Gedajlovic et al. 2012).Footnote 1

The purpose of this chapter is to take stock of recent scholarship, an endeavor that Boyer (1990) considered as critical for the growth of a professional field of study—rivaling knowledge creation, pedagogy, and application. Most previous reviews have been framed around topics such as succession (e.g., Daspit et al. 2016), entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation (e.g., Goel and Jones 2016), or methods (e.g., Evert et al. 2017). To complement these works, this chapter focuses on the most prevalent theories used in family business literature and identifies the most influential articles from each theoretical perspective. Our main purpose is to examine how different theoretical lenses have contributed to the understanding of the heterogeneous behaviors found among family-owned firms. We then further suggest additional research directions to expand the domain of family business studies.

Based on input from 19 well-established scholars in the field, we identified the five most prevalent theories used between 2006 and 2013. We then searched for the most frequently cited works using each theory to represent the state-of-the-art family business research. In all, 21 influential articles were identified and reviewed. While collectively these articles illustrate the diversity of family firms as an organizational form, they also shed light on the sources of this heterogeneity and help identify interesting research questions using these multiple theoretical lenses. These articles also point toward other perspectives that can help to deepen the understanding of family enterprises around the world.Footnote 2

Methodology

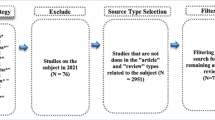

Building on the work of Chrisman et al. (2010), we used a three-step process for determining the articles to review in this chapter. First, we identified the most influential theories used in family business research since 2006. Next, we consulted an expert panel of 19 scholars whose main research focus is family businesses and asked them to identify the theories that were most influential in family business research. Five theories were mentioned at least ten times. In order of frequency they were: agency theory, resource-based view, stewardship theory, socioemotional wealth (SEW), and institutional theory.

Second, we searched the keywords and abstracts of articles in 35 journals that have published family business articles (cf., Debicki et al. 2009) between January 2006 and December 2013.Footnote 3 The search resulted in 167 family business articles. Together, these articles have been cited almost 20,000 times.Footnote 4 Finally, we used the average number of citations per year to determine the most influential articles for each theory.Footnote 5 We included the top five articles per theory but overlaps reduced the total number of articles to 21. Table 3.1 presents the articles ordered by citations per year.

Theoretical Perspectives

In the following sections, we review the articles by each theoretical perspective and highlight how they provide insights into the heterogeneity of family business behavior.

Agency Theory

Family firms were originally believed to have reduced agency costs due to the close emotional and biological bonds shared between members of the business (Jensen and Meckling 1976). However, subsequent work has suggested that family firms are not immune to agency issues. For instance, agency problems emanating from asymmetric altruism, as well as conflicts among owner and managers, owner-managers and lenders, majority and minority owners, and involved and uninvolved family members may all occur (Chrisman et al. 2004; Schulze et al. 2001; Villalonga et al. 2015). We highlight the most influential articles published between 2006 and 2013 that used agency theory as the main theoretical framework.

Chen et al. (2010)

This empirical study argues that family firms tend to have agency conflicts between dominant and minority shareholders. Contrary to nonfamily firms, which opt for tax aggressiveness, family firms are less tax aggressive. The authors conducted their panel study with data collected from the S&P 1500. Their hypotheses were supported as family firms display less tax aggressiveness when compared to nonfamily firms.

Chen et al. (2010) argue that such results are surprising because prior studies show that private firms are more tax aggressive than publicly traded ones and family firms tend to behave like privately held firms due to the concentrated ownership of the dominant family. However, the authors did find that the presence of long-term institutional investors can make a family firm more tax aggressive. Lower tax aggressiveness occurs in family firms seeking external financing, perhaps to mitigate concerns for family entrenchment. Family owners are willing to forgo the benefits of tax aggressiveness in order to ensure that the reputation of the firm is not damaged by incurring potential penalties from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006)

In exploring the different levels of performance in family businesses, this conceptual article explains how agency issues can lead to differences in resource allocations that impact family firm performance. The authors propose thatgovernance choices can influence the agency costs of family firms. They discussed four aspects of governance: (a) level and mode of family ownership, (b) family leadership, (c) involvement of multiple family members, and (d) planned or actual participation of later generations.

Concentrated ownership can benefit family firms through better monitoring because family owners have more incentives, power, and information to control managers. However, agency problems arise when either the majority family owner has too much power and incentive to exploit minority shareholders or when ownership is overly dispersed in conjunction with a nonowner CEO. Increased dispersion enhances the dilution of power, in which the nonowner CEO is able to act in a self-interested manner without fear of repercussions. Having a family CEO in the firm can prove beneficial for family shareholders because of increased alignment between the goals of owners and managers and more effective monitoring capabilities. Alternatively, the power the family has with a family CEO can create agency costs for minority shareholders, which may also manifest in family firms owned by multiple generations since ownership will be more dispersed, and some family members may fall in the “minority shareholder” group.

Dyer (2006)

This conceptual article uses agency theory to assess the “family effect” to clarify the contradictory research findings on family firm performance. Although the overlap in ownership and management in family firms can reduce monitoring costs, altruism and self-control inhibit the ability of family owners to monitor other family members in the firm (Schulze et al. 2001). Family firms are characterized as four types: (a) clan, (b) professional, (c) mom-and-pop, and (d) self-interested.

Each type possesses advantages and disadvantages for reducing agency costs. Clan and mom-and-pop family firms experience low agency costs due to common goals and values among the family and firm. Professional family firms tend to incur higher agency costs, which lead to formal monitoring processes to mitigate the effects of nepotism and opportunism. Self-interested family firms have the highest agency costs borne from the utilitarian and altruistic relationships that instill nepotism and the prioritization of the family interests over those of the firm.

De Massis et al. (2013)

This literature review provides key insights into how agency concerns can influence family firms’ investment in innovation. Family firms often experience intra-family conflicts that deter R&D investments, which lead to lower R&D intensity than found in nonfamily firms. One explanation is that family owners attempt to safeguard family wealth and preserve the unification of family ownership and management.

However, another view characterizes family firms as having lower agency costs resulting in better abilities to successfully introduce new products (Cassia et al. 2011). Family firms may have lower agency costs due to parsimonious governance structures that preserve family wealth by promoting the efficient allocation of resources (Carney 2005; Durand and Vargas 2003). The review highlights the importance of further research using agency theory to reconcile the contradictory views on family firms’ investments in innovation.

Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2009)

This conceptual article discusses why some family-controlled businesses display superior performance. To explain this phenomenon, the dual roles of the family owner-manager (Anderson and Reeb 2003) reduce agency costs, thereby increasing the amounts of resources being allocated for the long-term sustainability of the firm.

The authors based their arguments on the notion that family managers have more power, motivation, and knowledge to monitor the behaviors of other managers (Demsetz 1988; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006).

Agency Theory and Family Firm Heterogeneity

These articles show how agency theory can aid in understanding family firm heterogeneity. Agency costs borne by family members will lead to differences in strategic behavior. Family firms that have a controlling owner as the manager can establish a self-serving strategy due to the unchecked power they possess. Then again, firms owned and managed by family members can use their power to monitor and control strategy in a way that reduces agency costs. The studies presented above suggest that the strategic behavior of family firms may differ depending on the types and levels of involvement of family members in the ownership and management of the firm, goals pursued, and basis of resources (De Massis et al. 2014).

Resource-Based View

The resource-based view (RBV) implies that firms with bundles of resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable will attain sustainable competitive advantages that will be translated into superior performance (Barney 1991). Family firms may develop unique competitive advantages due to distinct resources emerging from family involvement such as social capital, survivability capital, patient capital, and human capital (Habbershon and Williams 1999; Sirmon and Hitt 2003). We highlight the most influential articles published between 2006 and 2013 that used the RBV as the main theoretical framework.

Arregle et al. (2007)

This conceptual article extends the RBV of the family firm to examine the development of a family firm’s organizational social capital (Sirmon and Hitt 2003). Social capital is identified as a potential competitive advantage for family firms because the established social capital of the family becomes embedded in the firm’s social capital. The influence of the family’s social capital on the development of the family organization’s social capital arises from the family having control of the firm, which results in the family shaping the firm’s identity and managerial rationalities.

Stemming from the notion that organizational social capital is shaped by employment practices (Leana and Van Buren 1999), the authors suggest that family social capital influences the human resource practices of the firm. Focus is also placed on the enhancement that interdependence among family members has on the social capital of the family and of the firm. The social capital of the family is thought to promote closure, which tends to lead to stronger relationships among individuals in the firm.

Dyer (2006)

In addition to agency theory, this conceptual article also uses the RBV perspective to explain the conflicting performance findings in the family business literature. In particular, family firms may experience human capital benefits through the employment of family members due to family employees being better trained, motivated, and flexible than nonfamily employees. However, the human capital of family firms may suffer when nonfamily members are not present in key positions as they can potentially enhance the management skills of the firm. Although the stocks of social capital held by family owners and managers will be potentially greater than those available to owners or managers lacking family ties, such stocks come at the expense of greater insularity when interacting with nonfamily employees.

The financial capital of the family firm also benefits from family ties as family managers are more likely to inject personal resources into the firm. The clan and professional family firms are categorized as having high family-specific assets that aid in achieving superior performance, whereas mom-and-pop and self-interested firms experience higher family liabilities through poor leverage of their resources. In sum, Dyer (2006) argues that the ideal type of family firm is the clan because of higher levels of family-specific assets and lower agency costs.

Pearson et al. (2008)

This conceptual article develops a model that uses the social capital of the family firm to explain the “black box” of familiness (Habbershon and Williams 1999). The authors apply the structural, cognitive, and relational dimensions of social capital (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998) to explain the potential emergence of family firm-specific resources. The structural dimension of social capital includes the network ties and the merging of family and organizational social capital. The cognitive dimension consists of shared vision and shared language that arises from a family’s influence on the firm. The relational dimension consists of the trust, norms, obligations, and identification that are embedded in the internal social capital of family firms.

As a result, these social capital dimensions described family firm capabilities based on information access such as the exchange of information, efficient action, and associability. In turn, information access leads to the collective goals, actions, and emotional support among family firm members.

Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2006)

In this article, the authors relied on the RBV to explore the antecedents of superior performance in family-controlled firms. Long-term orientation is considered one of the crucial factors that influences whether family-controlled firms are able to establish sustainable competitive advantages. In particular, family CEOs with longer tenures create an environment for leveraging resources by pursuing less risky endeavors, increased knowledge, and longer investment horizons. The benefits of long-term orientation are heightened when family firms have intentions to include subsequent generations in the firm, and the family retains decision-making control. However, resources utilized for long-term investments will diminish if the family focuses more on rent seeking or value expropriation.

The long-term orientation found in a family-controlled business can lead to strategies that will develop competencies through investments in R&D and long-term brand building. Also, lower agency costs associated with family control increases the availability of resources for long-term investments. Family-controlled firms are described as investing more in human resource practices to retain the embedded knowledge of their human capital. Relationships within family-controlled firms will also be nurtured over the long term in order to better leverage social capital and achieve long-term goals.

Eddleston et al. (2008)

This empirical study proposed that reciprocal altruism (identified as a family-specific resource) and innovative capacity (identified as a firm-specific resource) can contribute to the superior performance in family firms. The authors define reciprocal altruism as the “unselfish concern and devotion to others without expected return…whose primary effect is a strong sense of identification and high value commitment towards the firm”, (Corbetta and Salvato 2004: 358) to develop arguments about establishing organizational commitment and interdependence among family employees. They also argue that a firm’s innovative capacity is an indicator of an ability to invest in renewal and growth through entrepreneurial activities (McGrath 2001).

The study was conducted with 126 privately held firms (74 family firms). The findings suggested that both reciprocal altruism and innovative capacity positively influence family firm performance. Furthermore, the authors found two moderating effects. First, strategic planning enhances the positive relationship between innovative capacity and family firm performance but does not influence the relationship between reciprocal altruism and family firm performance. Second, technology opportunities positively moderate the relationship between reciprocal altruism and family firm performance but does not significantly impact the relationship between innovative capacity and family firm performance.

Resource-Based View and Family Firm Heterogeneity

The idiosyncratic assortment of resources found in family firms represents a key determinant of family firm heterogeneity (Chua et al. 2012). By reviewing these articles rooted in the RBV perspective, one can see how family firm heterogeneity is associated with varied resources. Not only do family firms possess different bundles of resources (Eddleston et al. 2008), they may differ in how resources are leveraged (Dyer 2006). This demonstrates that even when family firms possess similar resources, the management of these resources may lead to variations in how they are used and whether sustainable competitive advantages are obtained (Sirmon and Hitt 2003).

Stewardship Theory

Contrary to agency theory, stewardship theory argues that managers naturally align themselves with the principals’ goals to provide superior management of the firm (Davis et al. 1997). Based on the emotional and biological bonds shared among family members in the business, research has posited that steward-like behaviors are more prevalent in family firms (Corbetta and Salvato 2004). Although stewardship may be reduced if nonfamily members in the family firm are treated differently (Verbeke and Kano 2012), performance may be increased if a steward-like environment can be instilled in the firm. We highlight the most influential articles published between 2006 and 2013 that used stewardship theory as the main theoretical framework.

Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006)

In addition to their agency theory contributions, the authors used the stewardship perspective to propose that concentrated ownership allows the firm to enact steward-like tendencies by enhancing emotional bonds among members of a firm. The inclusion of nonfamily members either as owners or on the board may increase the steward-like behavior by keeping the controlling family in check when making decisions that could be self-serving or risky to other investors. This inclusion results in informed stewards who will be aligned with accomplishing the goals of the family firm. Similarly, the benefits of stewardship emerge when other family members are part of the top management team. However, stewardship may be hindered if these family members make up the dominant coalition of owners.

On the one hand, stewardship tendencies will increase when the family firm allows the entry of the future generations to increase the longevity of the firm, and the focus is placed on training the incoming generation. On the other hand, family firms may experience diminishing stewardship when conflicts arise from the appointment of successors. Also, additional conflicts can emerge if family members from multiple generations start to deplete firm resources.

Eddleston and Kellermanns (2007)

This empirical study assessed the effects of family relationships on the performance of 60 family firms in the Northeastern region of the US. This is one of the first studies to directly test the effects of altruism and relationships in family firms. Their main finding is that altruism has negative impacts on conflict but positively influences participative strategy processes. The use of participative strategy processes in the family firm will increase the proclivity of steward-like behaviors due to the family member’s commitment to the goals of the firm (Kellermanns and Eddleston 2004).

As a result, participative strategy processes have a significant influence on family firm performance, whereas family conflict will have detrimental effects on performance. Hence, the study reinforces the notion that stewardship enhances family firm performance.

Zahra et al. (2008)

This empirical study examined how a culture of commitment influences the strategic flexibility and competitive ability of family firms. Strategic flexibility is the firm’s ability to pursue new opportunities in response to competitive forces in the market. Using a sample of 248 family firms in the food processing industry, they test if family commitment enhanced strategic flexibility. Moreover, they test the influence of stewardship behavior on the relationship between a culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility. Stewardship orientation is argued to enhance the achievement of long-term organizational goals that emerge from reciprocal altruism, prosocial behavior, and mutual interdependence (Eddleston et al. 2008).

The authors found that strategic flexibility is positively related to a strong culture of family commitment and is partially influenced by the firm’s stewardship orientation. Stewardship orientation also had a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility. Thus, commitment to the family and steward-like behavior are proposed to enhance competitiveness in family firms.

Westhead and Howorth (2006)

This empirical study analyzed the effects of ownership and management structures on the performance and noneconomic objectives of 904 privately held UK family firms. The authors argued that the stewardship behavior of family firms will be limited because family owners and managers place greater importance on family goals than firm goals, and this lowers firm performance. However, having “outsiders” as board members or directors will curb the self-serving behaviors of the controlling family, which will enhance the goal alignment of all shareholders.

Their findings show that family ownership and management is not indicative of poorer performance in family firms, and that the inclusion of nonfamily executive directors in the board did not mitigate the importance of the controlling family’s non-pecuniary objectives.

Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2009)

As this article covers both the agency and stewardship perspectives, the notion of social embeddedness is used to explain competing views about family firm outcomes. The authors used four contexts of social embeddedness: structural, political, cognitive, and cultural-normative (Zukin and DiMaggio 1990). Structural embeddedness can lead to more stewardship behaviors to the extent that a family firm includes multiple family officers and managers in conjunction with nonfamily managers. Political embeddedness is argued to produce steward-like behaviors when family officers hold key managerial positions in the family firm.

Stewardship behaviors will dictate firm behavior when family rationales are embedded in the firm, and there is an alignment of the family firm’s culture with the socially minded founders. Additionally, the top executives’ stewardship will be influenced by how the executives are embedded in the firm; thus, more embeddedness will align the executives’ goals with firm performance.

Stewardship Theory and Family Firm Heterogeneity

As highlighted in the reviews discussed above, family firms are heterogeneous in the extent to which they exhibit behavior associated with stewardship. The strategic planning of family firms will be augmented depending on if the controlling family focuses on instilling an environment where stewardship can flourish. The family firm that displays steward-like behavior may hire more nonfamily managers to offset the potential self-serving behavior of other family members (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006). Also, family firms that are characterized as more innovative may invest more in new products or technologies owing to their stewardship orientation (Zahra et al. 2008).

Socioemotional Wealth

The application of the SEW concept in family firm research is based on the behavioral agency model (BAM) devised by Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia (1998), which is, in turn, a derivative of prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). The fundamental ideas are that firms are loss averse, and that family firms behave differently from nonfamily firms because of the owning family’s aversion to losing the SEW that accompanies control of the firm (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2011). Combined, BAM and SEW help explain the heterogeneous behaviors of family firms in managing the risks associated with various strategic behaviors (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2011) and their reluctance to professionalize (Vandekerkhof et al. 2015). Although noneconomic benefits may occur in all types of firms, applications of SEW to BAM indicate that family firms are more concerned with preserving these benefits. We highlight the most influential articles published between 2006 and 2013 that used SEW, usually in combination with BAM, as the main theoretical framework.

Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007)

This empirical study is the highest cited article in our list and is often used as the main SEW reference since it was the first to develop and employ the concept. Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007) argue that family owners are loss averse with respect to SEW (the affective endowments associated with control of the firm) instead of financial wealth.

Using a sample of 1237 family-owned Spanish olive mills, they evaluate the willingness of family owners to join a cooperative to increase firm performance. They found that most family-owned olive mills accept higher risk of lower performance in order to maintain family control, which suggests that family owners place a higher premium on the noneconomic benefits of the firm (SEW) than its economic benefits. The analysis found that family firms are more willing to take on risk when it involves retaining family control of the business, especially in businesses where family involvement is greater. The differences in risk-taking behaviors suggested that family owners may be either risk averse or risk seeking, depending on how they perceive threats to SEW associated with strategic actions.

Berrone et al. (2012)

This article reviews the main aspects of SEW and introduces the FIBER construct as one potential multidimensional measure of SEW. The authors identify five dimensions of SEW: (a) Family control and involvement: the control that the family exerts in firm decision-making, (b) Identification of family members with the firm, (c) Binding social ties: the social network ties the family possesses within and outside the family firm, (d) Emotional attachment of family members to the family firm, and (e) Renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession.

This multidimensional approach can be used to assess the distinct behaviors of family firms and the potential reference points in the strategic decision-making process. The authors propose this SEW perspective for examining a family firm to be advantageous as it does not ignore the possibility of self-enhancing behaviors, while highlighting the emotional and collaborative behaviors found in family firms.

Berrone et al. (2010)

This empirical study analyzed the environmentally conscious behavior of 194 publicly traded US firms (101 family firms). The sample came from manufacturing firms that are required to report their emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency through their Toxic Release Inventory program. Using both BAM and institutional theory, family firms are hypothesized to pollute less than their nonfamily competitors in order to preserve their SEW. In particular, family-owned manufacturers will be more sensitive to their reputation in the local community, in turn, making them more cognizant of their disposal of harmful waste.

The empirical results show that family-owned manufacturers tend to have better environmental performance than nonfamily firms. Also the environmental performance of family-owned manufacturers was influenced by geographic location. The geographic influence on environmental performance was explained by the owning family placing higher importance on preserving their reputation and social ties with the local community. The authors found that family CEOs did not influence environmental performance; however, having a CEO with stock ownership resulted in less concern for environmental demands in nonfamily manufacturers.

Chrisman and Patel (2012)

This empirical study uses the BAM and the SEW perspective to study family firm’s investments inR&D. They assess the contradictory views about family firm investment for the long term to explain family firm innovative behaviors. In particular, they analyze the R&D investment of 964 S&P 1500 companies (473 family firms). BAM suggests that family firms are loss averse with respect to the family’s SEW, which should result in lower investment inR&D. However, using the related theory of myopic loss aversion, they explain that some family firms will invest more in long-term R&D in order to achieve the long-term goals of the family firm even though most family firms invest less. In line with BAM, family firms were found to generally invest less in R&D than nonfamily firms, but the variability of R&D investments among family firms was greater. An interesting finding of this study is that family firms invested more in R&D than nonfamily firms when performance fell below aspiration levels.

The change in investment behavior occurs due to the family firm shifting their view of R&D investment from a gain perspective that induces risk aversion (when performance is aligned with aspiration levels) to a loss perspective that induces risk seeking (when performance is below aspiration levels). Consistent with the theory of myopic loss aversion, the study found that when the goals of the family firm are long-term oriented, the R&D investments of the family firm are higher regardless of firm performance.

Zellweger et al. (2012)

This empirical study sought to explain the different levels of importance that family firms place on SEW and determine if SEW has measurable financial value. The authors argued that SEW is tied to the family’s control of the firm, and this can result in family owners setting a higher selling price for the firms to nonfamily buyers.Footnote 6 Their model implies that the owner’s valuation of the firm is positively influenced by the level of current family ownership, duration of family ownership, and intentions for transgenerational control.

The authors used a sample of 230 family firms’ CEOs (84—Swiss and 146—German). Their empirical results showed that the extent of family control does not influence the valuation of the family firm. However, the duration of control did influence the German CEO’s valuation of the family firm. For both Swiss and German firms, the intention for transgenerational control had a positive influence on the perceived value of the firm. These findings are important because they establish that SEW indeed exists and influences the value placed on the firm by family owners (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2007).

Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Heterogeneity

As it is evident through the contributions provided by these articles and as suggested by the BAM, the different reference points that emerge from aversion to loss of SEW is a source of the heterogeneity of family firms. Interestingly, in both the types and amounts of SEW may result in different strategic decisions and behaviors among family firms. For example, a family firm focused on maintaining its reputation or social capital may tend to include more nonfamily employees, whereas a family firm that prioritizes transgenerational succession may display a long-term strategic orientation.

Institutional Theory

Institutional theory states that organizations will respond to mimetic, coercive, and normative pressures from the external environment in order to achieve or maintain legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Family firm researchers suggest that the idiosyncratic nature of family firms results in additional pressures and a different pattern of responses (Leaptrott 2005). Family involvement increases the firm’s propensity to respond to stakeholder pressures that may influence the image and legitimacy of the family and the firm, yet decreases the firm’s propensity to respond to pressures that may conflict with the goals of the family (Melin and Nordvquist 2007). Below, we highlight the most influential articles published between 2006 and 2013 that used institutional theory as the main theoretical framework.

Berrone et al. (2010)

This empirical study uses institutional theory as well as SEW to investigate the propensity of a family firm to respond to environmental regulatory pressures in order to protect its reputation. In addition to the findings highlighted earlier, the study found that the institutional pressures are more intense for geographically concentrated family manufacturers. By incorporating the SEW lens into institutional theory, the study provided insights into why family firms exhibit heterogeneous behaviors instead of purely isomorphic responses to institutional pressures.

Miller et al. (2011)

This empirical study covers the influence of ownership structure on the strategy and performance of firms. Rather than using agency theory, the authors argued that social context and institutional logics are associated with certain types of ownership (i.e., lone-founder vs. family owner) which influence the performance and strategic behavior of the firm. In order to compare lone-founder managers and family managers, the authors reviewed the strategic behavior and performance of 898 Fortune 1000 companies (146—lone-founder firms, 263—family firms, 492—other firms).

Based on the analysis, top managers from lone-founder firms follow an entrepreneurial logic because of the institutional pressures from stakeholders of the firm and other entrepreneurs. Also, they strive to acquire legitimacy through growing the firm and increasing the firm’s accumulated wealth and tend to self-identify more as entrepreneurs. On the other hand, managers from family firms possess familial logic and experience additional institutional pressures from other family members who reside inside and outside of the firm. These managers are more conservative and produce inferior shareholder returns. When comparing CEOs, those from lone-founder firms pursue a growth strategy and higher performance, which equate to superior returns for shareholders. In contrast, CEOs from family firms pursue legitimacy by fulfilling the needs of the family and are identified as family nurturers. Overall, family firms exhibit lower performance than lone-founder firms.

Gedajlovic et al. (2012)

This literature review covers the notion that institutional conditions moderate performance differences between family firms. More specifically, they suggest that positive and negative effects arise from the institutional conditions that family firms experience when they are located in an emerging or a mature economy. In terms of family firms operating in emerging economies, the authors identified three literature streams to categorize the positive effect that institutional conditions have on family firm performance. The first stream consists of articles that detail the successful performance of family firms arising from their capability to fill institutional voids in the emerging economy. The second stream refers to family-based networks that aid in market development through small-scale businesses. The final stream examines the ability of powerful families to take advantage of corrupt government officials and weak legal safeguards to appropriate wealth for themselves and their firms.

Then, the authors addressed two factors that explain the positive performance of family firms operating in mature economies. The first is that family firms are able to flourish in advanced economies due to better regulations, transparent financial markets, and institutions that mitigate potential principal-principal problems. The second is the efficient specialization and the comparative advantages of family firms that arise from their ability to excel in specialized functions. The authors later explained that the negative influence on performance for family firms in advanced economies arises due to conservative behavior in both strategic investment and implementation, which might eventually lead to dissolution.

Miller et al. (2013)

This study is a follow-up from the authors’ 2011 article using 263 family firms from the Fortune 1000. Here, the strategic conformity of family-owned firms are explored as an alternative to the SEW perspective. They argued that the institutional perspective offers a better explanation of strategic conformity than SEW because of the conflicting arguments found in the SEW literature when describing the family firms’ strategic planning (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2011). Strategic conformity is explored in family firms due to the fact that conformity is an antecedent to legitimacy (Deephouse 1996). The authors found that family firms will adhere more to industry norms than nonfamily firms. Particularly, family firms with afamily CEO will display higher conformity, and these effects are greater for later generational family CEOs. The analysis also showed that even though family firms exhibit higher conformity, there were no financial benefits attached. Similar to Berrone et al.’s (2010) findings, strategic conformity increases the SEW of the family firm without any financial gains passed on to shareholders.

Salvato et al. (2010)

This case study traces the Falck Group to examine the factors that influence exit and renewal strategies in family firms. The Falck Group is chosen because it is a multigenerational family firm established in the early 1900s. One of the key factors attributed to the decision for renewal is the legitimacy that results from maintaining the firm’s identity. The institutional identity developed from the firm’s history influences strategic choices and a hesitation to change in family firms, which results in family firms being more concerned with preserving their institutional integrity than their fit with the environment.

By studying the Falck Group’s transition from a steel producer to the renewable energy business, the authors highlight the importance of maintaining the institutional identity of an enterprising family. Despite the notion that only family members can promote continuity and institutional integrity in strategic decisions, nonfamily members in the firm can also initiate business change. Thus, family and nonfamily members can efficiently lead to radical changes in family firms. The main insight from the study is the importance of continuity and institutional integrity in transitioning from unstable to stable businesses. This is a result of the institutional identity being more deeply ingrained through the family’s values.

Institutional Theory and Family Firm Heterogeneity

These articles highlight how institutional theory can explain family firm heterogeneity. A fundamental premise of institutional theory is that organizations create different structures and strategies that are influenced by the interplay of both external and internal factors. Family firms that emphasize the institutional identity of the family will exhibit differing strategies than family firms that are more susceptible to pressures in the external environment. These responses to institutional pressures depend on the goals and governance of the family firm. Those that are more concerned with the continuity of the family firm through transgenerational succession will respond to institutional pressures different than family firms that place higher importance on appealing to nonfamily shareholders. Theinstitutional identity that the family manager places as a reference point for legitimacy will also influence the strategic behavior the family firm exhibits.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to assess the development of family business research between 2006 and 2013 by examining the 21 most influential articles that adopted the most commonly used theoretical lenses: Agency, RBV, Stewardship, SEW, and Institutional. This process generated several interesting observations.

First, the articles were published in ten different journals in the fields of family business, entrepreneurship, management, and finance. This signals a wide-ranging acceptance of family business research and bodes well for this field of study. Second, a preponderance of the work was empirical (57%), followed by conceptual articles (33%), and literature reviews (10%). While it is encouraging to note that the field has progressed to a stage where empirical studies are dominant, there seems to be a need to develop valid and reliable measures for primary research. For example, the recent work devoted to the generation of scales to measure SEW (Debicki et al. 2016; Hauck et al. 2016). Third, during the time frame used in our study, SEW has emerged as a major approach for studying the behaviors of family firms, accounting for three of the five most frequently cited articles. In contrast, institutional theory appears to be a major alternative to the SEW perspective as it provides opportunities to understand how family firms are influenced by their contexts and how they influence their contexts.

Fourth, all 21 articles are authored by researchers in North America or Europe, with all empirical samples from these regions as well. This reveals a pressing need to develop and test family business theory in other parts of the world. Particularly, it is expected that, by 2025, family firms from emerging economies will account for 37% of all companies with annual revenues of more than US$1 billion, up from 26% in 2010 (Economist 2014, p. 13). Fifth, it is interesting to note that 45 researchers co-authored these 21 articles. While there was one single-authored article (Dyer 2006), teams of two (six articles), three (seven articles), and four (five articles) are most common. Two articles were authored by five-member teams. Among individual authors, Miller and Le Breton-Miller were co-authors of five articles each, Kellermanns had four articles, and Chrisman and Gomez-Mejia each contributed three. Also, Gomez-Mejia co-authored the two most cited articles. Together, these five researchers co-authored 13 of the 21 (62%) articles featured in our review.

Directions for Future Research Using Agency and/or Stewardship Theory

Even though a common focus in family business research is family firm heterogeneity, many studies follow a more homogenous approach by focusing on traditional family structures (Jaskiewicz and Dyer 2017). Future research can continue exploring the potential distinctions between stewardship behaviors and agency costs in family firms comprised of nontraditional family systems such as single parents, blended families, and families separated by divorce or distance.

First, future research is needed to investigate the conflicting governance strategies that affect performance under multiple ownership structures (family and nonfamily) arising from nontraditional family structures (e.g. Madison et al. 2016; Villalonga et al. 2015). Since it would be more desirable if family and nonfamily managers behaved as stewards rather than agents, future research is need to understand the mechanisms needed to encourage stewardship behaviors. Researchers need to abandon the implicit assumption of “spontaneous motivation” (cf. Drucker 1954, p. 278) and begin to investigate how managers might be motived to act like stewards.

Second, certain considerations deserve attention to explore deviations from the traditional family often assumed in family business research (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006). Taking nontraditional families into consideration can explain the differences in family firm behavior. For instance, the majority of family firm studies using an agency or stewardship perspective assume that the traditional family represents the dominant coalition (Jaskiewicz et al. 2017). However, researchers should also consider the extent to which opportunistic or steward-like behavior will emerge if other family relationships (e.g. divorced parents, in-laws, single parents, and blended families) are included. For example, what is the impact of divorce among members of the dominant coalition in terms of the potential for and severity of agency problems? Other situations may also generate the potential for agency conflicts or steward behaviors in family firms. For example, the inclusion of step-children and step-siblings adds family members that have an interest in the firm who are not related by blood to all of the other family members, thereby increasing the possibility for conflicts and disagreements.

Furthermore, using an agency lens implies that the division of the family into opposing factions will influence the likelihood of self-interested behaviors and the race to the bottom (Zellweger and Kammerlander 2015). As a result of the potential increase in self-interested behaviors resulting from divorce or the involvement of multiple families, higher levels of monitoring or side payments may be necessary. These activities or actions can destroy trust and divert resources from more productive pursuits, which will negatively impact performance.

Alternatively, employing a stewardship perspective may be needed to explain different behaviors that emerge in the event of a divorce between members of the dominant coalition or the blending of two families. For instance, the dominant coalition may attempt to maintain the bond between family members in the firm, which will promote stewardship. This may result in increased altruistic behaviors that signal that the firm and the family are still important to the dominant coalition, even if the marriage did not work or the members are not from the nuclear family. The dominant coalition may also strive to preserve the family’s goals that are in place to provide a rallying point for the family to counteract the impact of a divorce or a blended family.

Recent work suggests that asymmetric information may be a more serious and pervasive concern for family firms than opportunism as it appears to be a root cause of deviant behavior and an inhibitor of goal alignment even when the inclination of participants is to cooperate (Chrisman et al. 2014). Similarly, the potential for opportunism may be increased by adverse selection. Unfortunately, studies using agency theory have not fully considered the ramifications of either asymmetric information or adverse selection and neither are incorporated into the precepts of stewardship theory. Future studies should seek to address these limitations.

Directions for Future Research Using Resource-Based View, Socioemotional Wealth, and/or Institutional Theory

Since Berrone et al. (2012) proposed FIBER, there have been at least two different SEW measures developed (Debicki et al. 2016; Hauck et al. 2016). Future research can assess the combined and individual effects of a family firm’s resources on the SEW and governance structure of the family firm (Debicki et al. 2016). Particularly, the resources emanated from the interaction between the family and the business may allow family firms to develop competitive advantages that can be suitable for operating in particular situations to achieve a variety of goals using a variety of governance structures (Carney 2005).

Longitudinal studies built on the precepts of BAM may be beneficial in explaining how aversion to the loss of SEW may potentially shift depending on the family firm’s size, age, and industry, as well as its resources and governance structure. For example, family firms may be more averse to a decline in the well-being of family members in early stages of development, whereas the reputation of the family firm may be a higher priority in later stages of development. Similarly, the SEW importance (SEWi) scale (Debicki, et al. 2016) may be used to further explore strategic conformity in family businesses. For instance, the difference in importance placed on certain dimensions of SEW may dictate how receptive the family firm is to conforming to external pressures, leading them to set different reference points for decision-making.

Researchers should further explore how family firms’ approach to entrepreneurship (causal or effectual) influences responses to institutional pressures. It may be that family firms, which use a causal approach to innovation, will be likely to succumb to institutional pressures than family firms that use an effectual approach. Furthermore, whether the pressure for conformity to family history, industry norms, or the behaviors of other family firms hold the greatest sway may lead to differences in the levels and types of conformance, as well as differences in the ability of family firms to engage in behavior that diverges from the status quo.

Directions for Future Research Using Other Theories

Aside from the theories discussed above, scholars might wish to consider the use of other theories such as transaction cost theory and stakeholder theory in future family business research. For example, transaction cost theory is useful for assessing the idiosyncratic behaviors of family firms (Verbeke and Kano 2012) and prior research has found that family firms prefer to rely more on kinship ties than subcontracting outside of the family domain (Memili et al. 2011). Similarly, since family firms have been theorized to possess distinct stakeholder salience perspectives, stakeholder theory appears to hold promise for assessing the behaviors of family firms (Mitchell et al. 2011).

One area that both transaction cost and stakeholder theories could contribute is the role of in-laws, a topic that has been largely neglected in family business research (for a notable exception see Santiago 2000). In many family businesses, the inclusion of in-laws is a natural evolution of the family business system. Alternatively, the exclusion of in-laws may also influence the system. However, whatever the practice on the business front, families must bring outsiders into the system in order to survive. For example, research is needed to determine the extent to which the firms run by the families of in-laws might be viewed as potential alliance partners and how the inclusion of in-laws increases or dilutes the human asset specificity and SEW of the firm. Similarly, the involvement of in-laws in a family business may affect stakeholder salience considerations by expanding the number of salient stakeholders and/or altering perceptions of the power, legitimacy, and urgency of existing stakeholders. Such a shift could impact the goals, governance, resources, and subsequent performance of a family firm and is therefore a relevant topic for future research.

In conclusion, we expect that researchers in the field can learn much from the articles and theoretical perspectives discussed in this chapter. Collectively, they illustrate that the field is well underway in its journey to develop more robust theoretical understandings of this distinctive form of organization. We hope this chapter will facilitate the continuation of the journey!

Notes

- 1.

Also see review articles at http://journals.sagepub.com/topic/collections/fbr-1-selected_review_articles/fbr

- 2.

Our original purpose was to review the top five articles per theory; however, we ended with 21 articles because 4 articles used more than one of the theories.

- 3.

American Economic Review, Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Business Ethics Quarterly, Corporate Governance: An International Review, California Management Review, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Family Business Review, Harvard Business Review, Human Relations, International Small Business Journal, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business Venturing, Journal of Family Business Management, Journal of Family Business Strategy, Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Journal of Small Business Management, Leadership Quarterly, Long Range Planning, Management Science, Organizational Dynamics, Organization Science, Organization Studies, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Small Business Economics, Strategic Management Journal, Sloan Management Review, and Strategic Organization.

- 4.

In order to allow a fair representation of citations per year, the searches for influential articles were limited to family business articles that were published between January 2006 and December 2013. However, articles published after December 2013 were considered for enhancing the review and future research directions.

- 5.

Citation counts were conducted using the Google Scholar’s database on September 4, 2017.

- 6.

This premium disappears if the firm is sold to another family member. The authors explain that this is because when the firm is sold within the family, socioemotional wealth (SEW) is maintained.

- 7.

Articles highlighted in the review are shown in bold.

References

Articles highlighted in the review are shown in bold.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328.

Arregle, J. L., Hitt, M. A., Sirmon, D. G., & Very, P. (2007). The development of organizational social capital: Attributes of family firms. Journal of Management Studies, 44 (1), 73–95.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (1), 82–113.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25 (3), 258–279.

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265.

Cassia, L., De Massis, A., & Pizzurno, E. (2011). An exploratory investigation on NPD in small family businesses from Northern Italy. International Journal of Business, Management and Social Sciences, 2(2), 1–14.

Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? Journal of Financial Economics, 95 (1), 41–61.

Chrisman, J. J., & Patel, P. C. (2012). Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 55 (4), 976–997.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Litz, R. A. (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and nonfamily firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 335–354.

Chrisman, J. J., Kellermanns, F. W., Chan, K. C., & Liano, K. (2010). Intellectual foundations of current research in family business: An identification and review of 25 influential articles. Family Business Review, 23(1), 9–26.

Chrisman, J. J., Memili, E., & Misra, K. (2014). Non-family managers, family firms, and the winner’s curse: The influence of non-economic goals and bounded rationality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1103–1127.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Steier, L. P., & Rau, S. B. (2012). Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1103–1113.

Corbetta, G., & Salvato, C. (2004). Self-serving or self-actualizing? Models of man and agency costs in different types of family firms: A commentary on “comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence”. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 355–362.

Daspit, J. J., Holt, D. T., Chrisman, J. J., & Long, R. G. (2016). Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: A multiphase, multistakeholder review. Family Business Review, 29(1), 44–64.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47.

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., & Lichtenthaler, U. (2013). Research on technological innovation in family firms: Present debates and future directions. Family Business Review, 26 (1), 10–31.

De Massis, A., Kotlar, J., Chua, J. H., & Chrisman, J. J. (2014). Ability and willingness as sufficiency conditions for family-oriented particularistic behavior: Implications for theory and empirical studies. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(2), 344–364.

Debicki, B. J., Matherne, C. F., Kellermanns, F. W., & Chrisman, J. J. (2009). Family business research in the new millennium: An overview of the who, the where, the what, and the why. Family Business Review, 22(2), 151–166.

Debicki, B., Kellermanns, F., Chrisman, J. J., Pearson, A., & Spencer, B. (2016). Development of a socioemotional wealth importance (SEWi) scale for family firm research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(1), 47–57.

Deephouse, D. L. (1996). Does isomorphism legitimate? Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 1024–1039.

Demsetz, H. (1988). The theory of the firm revisited. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 4(1), 141–161.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Drucker, P. (1954). The practice of management. New York: Harper & Row.

Durand, R., & Vargas, V. (2003). Ownership, organization, and private firms’ efficient use of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 24(7), 667–675.

Dyer, W. G. (2006). Examining the “family effect” on firm performance. Family Business Review, 19 (4), 253–273.

Economist (2014, November 1). Family companies: Relative success. (2014, November). The Economist, 410(8907), 12–13. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2014/11/01/relative-success.

Eddleston, K. A., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2007). Destructive and productive family relationships: A stewardship theory perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 22 (4), 545–565.

Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Sarathy, R. (2008). Resource configuration in family firms: Linking resources, strategic planning and technological opportunities to performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45 (1), 26–50.

Evert, R. E., Martin, J. A., McLeod, M. S., & Payne, G. T. (2017). Empirics in family business research: Progress, challenges, and the path ahead. Family Business Review, 29(1), 17–43.

Gedajlovic, E., Carney, M., Chrisman, J. J., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2012). The adolescence of family firm research: Taking stock and planning for the future. Journal of Management, 38 (4), 1010–1037.

Goel, S., & Jones, R. J. (2016). Entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation in family business: A systematic review and future directions. Family Business Review, 29(1), 94–120.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52 (1), 106–137.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653–707.

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25.

Hauck, J., Suess-Reyes, J., Beck, S., Prügl, R., & Frank, H. (2016). Measuring socioemotional wealth in family-owned and-managed firms: A validation and short form of the FIBER scale. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(3), 133–148.

Jaskiewicz, P., & Dyer, W. G. (2017). Addressing the elephant in the room: Disentangling family heterogeneity to advance family business research. Family Business Review, 30(2), 111–118.

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J., Shanine, K., & Kacmar, M. (2017). Introducing the family: A review of family science with implications for management research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 309–341.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analayis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Kellermanns, F. W., & Eddleston, K. A. (2004). Feuding families: When conflict does a family firm good. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(3), 209–228.

Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2006). Why do some family businesses out-compete? Governance, long-term orientations, and sustainable capability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30 (6), 731–746.

Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2009). Agency vs. stewardship in public family firms: A social embeddedness reconciliation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33 (6), 1169–1191.

Leana, C. R., & Van Buren, H. J. (1999). Organizational social capital and employment practices. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 538–555.

Leaptrott, J. (2005). An institutional theory view of the family business. Family Business Review, 18(3), 215–228.

Madison, K., Holt, D., Kellermanns, F. W., & Ranft, A. L. (2016). Viewing family firm behavior and governance through the lens of agency and stewardship theories. Family Business Review, 29(1), 65–93.

McGrath, R. G. (2001). Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 118–131.

Melin, L., & Nordqvist, M. (2007). The reflexive dynamics of institutionalization: The case of the family business. Strategic Organization, 5(3), 321–333.

Memili, E., Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Chang, E. P. C., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2011). The determinants of family firms’ subcontracting: A transaction cost perspective. Journal of Family Business Strategies, 2(1), 26–33.

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Family Business Review, 19 (1), 73–87.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Family and lone founder ownership and strategic behaviour: Social context, identity, and institutional logics. Journal of Management Studies, 48 (1), 1–25.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Lester, R. H. (2013). Family firm governance, strategic conformity, and performance: Institutional vs. strategic perspectives. Organization Science, 24 (1), 189–209.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., Chrisman, J. J., & Spence, L. J. (2011). Toward a theory of stakeholder salience in family firms. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(2), 235–255.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Pearson, A. W., Carr, J. C., & Shaw, J. C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32 (6), 949–969.

Salvato, C., Chirico, F., & Sharma, P. (2010). A farewell to the business: Championing exit and continuity in entrepreneurial family firms. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22 (3–4), 321–348.

Santiago, A. L. (2000). Succession experiences in Philippine family businesses. Family Business Review, 13(1), 15–35.

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., Dino, R. N., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. Organization Science, 12(2), 99–116.

Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 339–358.

Vandekerkhof, P., Steijvers, T., Hendriks, W., & Voordeckers, W. (2015). The effect of organizational characteristics on the appointment of nonfamily managers in private family firms: The moderating role of socioemotional wealth. Family Business Review, 28(2), 104–122.

Verbeke, A., & Kano, L. (2012). The transaction cost economics theory of the family firm: Family-based human asset specificity and the bifurcation bias. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1183–1205.

Villalonga, B., Amit, R., Trujillo, M. A., & Guzmán, A. (2015). Governance of family firms. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 7, 635–654.

Westhead, P., & Howorth, C. (2006). Ownership and management issues associated with family firm performance and company objectives. Family Business Review, 19 (4), 301–316.

Wiseman, R. M., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (1998). A behavioral agency model of managerial risk taking. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 133–153.

Zahra, S. A., Hayton, J. C., Neubaum, D. O., Dibrell, C., & Craig, J. (2008). Culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility: The moderating effect of stewardship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32 (6), 1035–1054.

Zellweger, T., & Kammerlander, N. (2015). Family, wealth, and governance: An agency account. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(6), 1281–1303.

Zellweger, T. M., Kellermanns, F. W., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (2012). Family control and family firm valuation by family CEOs: The importance of intentions for transgenerational control. Organization Science, 23 (3), 851–868.

Zukin, S., & DiMaggio, P. (Eds.). (1990). Structures of capital: The social organization of the economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Odom, D.L., Chang, E.P.C., Chrisman, J.J., Sharma, P., Steier, L. (2019). The Most Influential Family Business Articles from 2006 to 2013 Using Five Theoretical Perspectives. In: Memili, E., Dibrell, C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity among Family Firms. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-77675-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-77676-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)