Abstract

Family business narratives connect the past, present, and future. This chapter offers an initial conceptualization of the parts of narratives dedicated to myths, through a systems view of the family business. Bridging literatures from different fields ranging from history to strategic management, family psychotherapy, and anthropology, we suggest a dynamic process of myth formation and transformation along with its impact on both family and business systems over the life cycle.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Family stories are the grist of social description and the symbolic coinage of exchange between generations (Thompson 2005). Historical narratives about managers and organizations connect the past, present, and future of an organization. These narratives are constructed to make sense of what was done in the past and its relation to the present, in a way they can be appropriated, mobilized, and used by different audiences to achieve different goals. The success of an organization seems therefore dependent on the ability of its managers to skillfully develop historical narratives that create a strategic advantage (Foster et al. 2017).

Questioning the relevance of this statement in family businesses entails accounting for an additional level of complexity. These businesses represent a unique organizational form where family and business systems interact and influence each other. The construction, transfer, influence, and target of narratives all relate, to a certain degree, to the distinctive family system. Depending on the extent to which the family overlaps with the business, business narratives will be intertwined with or inseparable from family narratives. These narratives aim to achieve not only business-oriented goals but also family-oriented goals. As such, they are intended for an extended circle of stakeholders, embracing both business and family systems.

Given that historical narratives are “verbal fictions, the contents of which are as much invented as found” (White 1978), the way in which they are constructed and told, the parts of reality which are chosen, left, invented, or reinvented, inform us immensely about the cognitive and affective map of the family in business. The related stories are not only remembered fragments of a real past, neither only clues to collective consciousness and personal identity, but also a form of the past still alive in the present (Thompson 2005).

Over the last decade, narratives have been of growing interest to both business historians and strategic management scholars, even if traditional business history has only reluctantly and recently come to reflect on the concept (Mordhorst and Schwarzkopf 2017). Business historians argued that family businesses are a fascinating subject of study and called for the use of research methodologies including longitudinal and comparative historical perspectives (Colli 2011). In organizational studies, scholars recognized the family business as a natural and special empirical ground to investigate the role of history in organizational life (Hjorth and Dawson 2016).

To date, little is known about the nature of family business narratives, their characteristics and process of development, or transmission across generations. Existing studies are scarce and remain at the embryonic stage of understanding how and when stories are told in family businesses (e.g., Johansson et al. 2014; Thompson 2005). In addition, while business historians seem to agree on the strategic impact of historical narratives as a competitive advantage in organizations, there is a lack of conceptual and empirical studies on the strategic usefulness of family business narratives for family and organizational outcomes.

We contribute to this literature by taking a closer look at “family myths”—a fundamental part of narratives in family businesses. Althoughhistorical narratives mention the same event, the reality is scattered across a multilayered structure and presented through different lenses, as Lévi-Strauss (1966) puts it in his arguments for the mythical nature of history. Historical narratives do not reproduce the events they describe; rather, they guide our thoughts about the events in a certain direction and charge our thinking with emotional valences (White 2002). This allows us to consider the historical narrative as an extended part of the myth. Myths are transmitted within a family system by framing the context in which strategic life choices of family members must be made (Thompson 2005), just as organizational myths delineate strategic choices of the business (Gabriel 2004).

This chapter is an attempt to open the black box of family business historical narratives in order to unlock their characteristics, processof production, and impact on the family business over the life cycle. It offers a conceptual framework based mainly on literature from business history, family business, and family psychotherapy. While we borrow from these fields, we also give back and contribute to ongoing discussions by bridging diverse perspectives. While the family psychotherapy literature focuses primarily on the family level of analysis, the business history and management studies emphasize narratives related to business development and managers’ contributions over time. In this chapter, these perspectives amalgamate to appear in myths, with this overarching view being an attempt to reconcile fields with different theories, research traditions, and vocabulary. By doing so, it lays the foundation to stimulate future complementary and interdisciplinary research efforts. This is true in the case of business history, where the established paradigm has left little space for cross-fertilization with other social sciences, except for economics. In particular, mythshave not been a traditional object of study for business historians, since they tend to be traditionally less interested by the history of mentalities or representations than culture and political historians, apart from a few exceptions (Holt and Popp 2013; Lyna and Van Damme 2009; Popp 2015; Varje et al. 2013). Although the connection to family business studies has been currently more active (Colli 2011; Colli et al. 2013), it still remains a recently opened avenue for collaboration.

The chapter is structured as follows. First, we articulate the nature of historical narratives in business history and management literature. We then transpose it to the family business context while emphasizing different typologies. Second, we focus on the “myth” type of narrative and present its characteristics using a systems view of family business by borrowing from organizational, anthropological, and psychotherapy perspectives. We then present an account of the impact it exerts along with its dynamics of construction, deconstruction, and transmission over time. Finally, we conclude with chapter implications, methodological considerations, and future research directions.

The Nature of Historical Narrative

Historical Narrative as an Input or Output

Given the acknowledged strategic dimension of historical narratives, we start by presenting this terminology from the perspective of history and management studies.

For historians, narratives are both an input and an output. When researchers collect personal accounts from those involved in past family and/or business events, narratives arise as a source. The same is true when historians collect stories told within the family circle about a central and critical past event (or set of events), including the associated psychological and physical action responses.

Historical narratives are also the final product of most historical research, presented in the form of a structured description plotting the “history” of an organization. Historical writing practices are grounded in narratives and the most used literary genre which (historians and business historians) present their work in (Mordhorst and Schwarzkopf 2017). This is problematic as it sometimes blurs the limits between stories and rigorous historical research.

The narrative as an input needs to be distinguished from the narrative as an output as both have very strong potential effects on reality and need to be considered critically. This is especially the case for families where narratives also convey a political role (Ochs and Taylor 1992).

Toward a Typology of Narratives in Family Business

From the perspectives of family business and management literature, Smith (2017) offers a distinction between story and narrative: A story is a narration of events containing basic features such as setting, plot, characters, and a sequence of events in a logical manner with a beginning, a middle, and an end. A narrative is an overarching organizational structure designed to facilitate the recounting of sequential events and experiences. The author considers that although all stories are narratives, not all narratives are stories.

Narrative as a tale, story, or memory is not history. The telling of temporarily ordered past events (Ricœur 1984) is not “the past” either. In his challenging reflection on memory and forgetting, Augé (2004) shows that memory is made of traces of past events, characters, and spaces that have escaped forgetting. People or events are not forgotten but the memory of them is.

Historians have recognized for a very long time that they have to work with the limitations of the material (Evans 1997). People in the past consciously lived a story they believed in, and historians cannot satisfy themselves just by reproducing it. Therefore, any rigorous and scientific historical endeavor has to deconstruct narratives by looking at hidden meanings, flaws and contradictions as much as putting them into contemporary context.

A key element here is the understanding that there is no such thing as unmediated narratives. Narrative represents the past in the present—in our case, stories and tales told in families and/or business communities. While they are parceled, they connect to issues that are contemporary for the tellers of narratives. A significant contribution of recent research in oral history is that collected narratives are impacted by the general and specific contexts in which they are told or recalled (Abrams 2016). Stories are “things to think with” that are used by individuals or groups for various purposes including to build “business romance” (Smith 2017).

Summerfield (2004) warns us not to take oral testimonies and narratives as disconnected from surrounding discourse: The cultural approach to oral history suggests that narrators draw on public discourses in constructing accounts of their pasts for their audiences. In addition to endeavoring to compose memory stories, they seek composure, or personal equanimity, from the practice of narration. Translating this approach to the context of families and family business, narrators tend to construct a discourse according to genres available and adapt it to their target audience. For instance, a tale of past business failure by family members could be narrated in different ways. It could be told through a “cold” analysis of factors that led to the problems, with a distant stance toward individual responsibility through “objective” measurement and contextualization. Alternatively, it could be narrated and plotted with more drama and moral judgment, in order to serve as a lesson for next generations, including warnings of errors not to be repeated.

In the context of family business, research seems to focus on narratives related to the family’s major events inrelation to the business. As such, researchers referred to narratives while coining different labels. Thompson (2005) calls it the “cultural transmission”, whereas Jaskiewicz, Combs, and Rau (2015) consider the easily recalled narratives as part of the “family’s entrepreneurial legacy”. These authors identify two forms of narratives often expressed by family members in their study: (1) The narratives about past entrepreneurial achievements shared in detail and with pride, such as how a family member engaged in entrepreneurship to start or reinvent the firm, and (2) the narratives about the family’sresilience in the face of challenging and threatening situations. Narratives appear to be particularly relevant as vehicles for the transmission process to the next generation to ensure family business continuity.

Whether part of the legacy or as cultural transmission, elements of narratives include, although not restricted to, myths, tales,and rituals relative to certain characters (heroes, fools, clowns, and so forth) or situations with plot elements (conflicts, deceptions, accidents, crises, and so forth). As Gabriel (2004) puts it, myths are useful in analyzing contemporary social and organizational realities. Feinstein and Krippner (1989) even consider that family myths are as much intrinsic to contemporary organizations as they are to archaic ones. Family myths are therefore of contemporary relevance to family businesses as they evolve in a world characterized by increasing globalization, terrorism, crises, digitalization, and social problems. As such, this chapter focuses on the myth aspect of narratives, presenting a first but fine analysis of its characteristics and process of construction or destruction over time.

Family Business Myth as a Dynamic Process: Toward Its Conceptualization for Favorable Outcomes

Understanding and delineating myths in family business requires accounting for the myths at the intersection of the subsystems comprising it.

Theoretical Framework: A Systems View

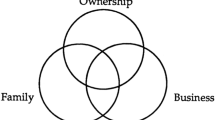

Family business is an open and structurally complex system comprising three interacting subsystems—family, business, and ownership (Gersick et al. 1997). The success of any family business depends on the way these subsystems interact and relate to one another over time (McClendon and Kadis 2004).

The family subsystem consists of an emotional and multigenerational unit where the functioning of different members is interdependent (Bowen 1978). Actions of one family member affect and influence the actions of all other members and the system as an entity. In addition to providing traditional security and economic needs, the family subsystem has the objectives of meeting emotional needs, maintaining integrity and cohesiveness, and family commitment toward satisfying the needs of the family (Hess and Handel 1994; Kantor and Lehr 1975; Kepner 1983).

In contrast to the family, a business is mostly considered as a rational subsystem, characterized by the interdependence of people whose membership is generally determined by competence. The goalsof the business subsystem are largely objective, seeking environmental adaptation and control, and effective functioning of the business, by generation of goods and services through organizational task behavior (Kepner 1983; Rosenblatt et al. 1985). The ownership subsystem is intended to meet the needs of the shareholders who can be more or less attached to the business, pursuing financial and non-financial objectives to different extents.

Adding to these subsystems, the individual and the environment appear as key parts of the family business “bull’s-eye system” as well (Pieper and Klein 2007).

Therefore, a myth might gravitate around the individual, family, business, and wider socio-cultural environment. Figure 20.1 presents a systems view of family business myths with these different levels of interdependence.

Characteristics and Composition of Myths

Etymologically, myth comes from the Greek “mythos”, referring to a speech, thought, or story. While it is difficult to find a single and commonly agreed-upon definition of myth among scholars, two general predominant perspectives of myths seem to exist (Eliade 1963; Ellwood 1999). Archaic societies view myth as a true story that is precious, sacred, exemplary, and significant. Modern societies see myth more as fiction or illusion. Referencing the works of Joseph Campbell (1968), myths throughout the world give an identical message (Ellwood 1999) although their morphology changes.

The core issue to be considered when studying myth is whether the myth is “alive” or not. A myth is alive if it delivers true stories with supernatural characters or archetypal categories of individuals, which supply models for human behavior and as such give meaning and value to life. As Ellwood (1999) puts it, myth is universal and has transcendent cultural settings to provide general models of the human predicament and ways out of it.

Myths have been studied from many angles primarily psychological, philosophical, anthropological, historical, and organizational. For the understanding of family business myths, it is important to refer to relevant perspectives informing different dimensions. These dimensions are not exclusive but interact with and build upon each other: Socio-cultural myths, business (organizational) myths, individual (personal) myths, and family myths.

Socio-cultural myths allow us to tackle transmission questions inspired by Bourdieu (1986) around what aspects of a family’s material and cultural capital can be transmitted and how this is to be achieved (Thompson 2005). Cultural capital is an important part of family transmission, beyond the ownership and social networks capital (Bourdieu 1986) found in family business.

Organizational myths revolve around the myth of creation as the essence of organizational existence. Existential psychology (Becker 1962, 1973) argues that organizations exist to provide a framework of myth which makes action possible. Organizations are created and sustained for the purpose of providing meaning to their members, which in turn builds their identities. The myth concept emerges under the assumption that organizations are potentially immortal (Schwartz 1985).

Myth in organizations refers to a symbolic approach of organizations (Alvesson and Berg 1992; Strati 1998). Representation is the fundamental form of narrative knowledge. It does not convey factual knowledgeas much as it transmits a “forma mentis”,which is a cognitive grid used to interpret experience and the way people perceive internal and external reality. Such stories express powerful emotions of anger, guilt, pride, and/or anxiety, capturing the diverse experiences of organizational members. Once captured, members can make sense of and endure these experiences, stimulating their desire for success or survival (Schwartz 1985).

Despite their relevance, organizational stories went largely unnoticed in mainstream organizational theory and social research (except ethnography research on workplace relations) until 20 years ago. Scholars noted an increasing academic interest in organizational storytelling causing a re-awakened attention to myth, tales, and fables for analyzing power and politics, strategy, emotions, fantasies, rationality, ethics and morality, identity, communication, culture, management, learning, and practices in organizations (Gabriel 2004).

Through the medium of myth, the code allowing knowledge to be derived from observation and interpretation of reality is transmitted. Official organizational narratives are reproduced in organizational rituals, advertisements, websites, or official publications that reflect the qualities managers would hope to embody. Examples include narratives of great achievements, missions successfully accomplished, dedicated employees, heroic leaders, or crises successfully overcome (Gabriel 2004).

In family business, the individual founders and entrepreneurs are commonly referred to as myths. Their personal business journeys are told as journeys of discoveries and survival (Gabriel 2004). Some go so far as to mythologize their skills by telling their family business story in terms of inherited instinct from mythical ancestors (Thompson 2005).

While socio-cultural, organizational (business), and individual (personal) myths are all relevant, compared to non-family business myths, focus is needed on the family subsystem as the distinctive dimension. Family is driven by transgenerational heritage and legacy that are consciously or unconsciously intended and are passed on as a burden or as a blessing (Böszörményi-Nagy and Spark 1984). Family myths become well-integrated beliefs shared by all family members, with symbolic contents and personal emotional experience attached to them. They also contain pseudo-secrets (real or imagined), often related to the family’s past and its ancestors (Seltzer 1989).

In his study on business families, Thompson (2005) observes how family stories include examples of family struggles, disasters, or breaches such as desertion or divorce. These stories become family legends mainly because of the mystery surrounding them. This mystery is often linked to negative emotions such as anger or bitterness, following a separation, for example, even though the descendants know nothing about these ancestors. If mystery—a catalyst of myth—is repeated from generation to generation, it can become a particularly powerful family script.

The original formulations of family myths date back to Ferreira (1963) and were mainly developed in the family psychotherapy field. Those myths are considered “a series of fairly well-integrated beliefs shared by all family members, concerning each other and their mutual position in family life, beliefs that go unchallenged by everyone in spite of the distortions which they may conspicuously imply” (Ferreira 1963, p. 457). Following Van der Hart, Witztum, and de Voogt (1989, p. 60) anthropological accounts of family myths, it is possible to limit the concept of family myth here to “shared traditional oral tales told by the family and its members about the family and its members”.

Family myths can be irrational with their own logic (Seltzer 1989). Lévi-Strauss (1966, 1968) used the metaphor “orchestra score” to refer to a mythical corpus. Elders are the bearers of culture through collective institutionalized practices. They subconsciously transmit basic messages to the younger generation. It is the transmission of this “score” originating in the past or tied to past events that has the power to direct familial pathways in the present.

Similar to the “family score” of Lévi-Strauss, Ancelin Schützenberger (1998) refers to the “family code” as a representation of learned reactions grounded in family history and the family’s genetic and historic relatedness. The “family myth becomes clear when you understand the system, that is the sum of mutually interdependent units” (Ancelin Schützenberger 1998, p. 20). It manifests itself through an operational pattern in the form of rites of functioning, which can be either functional or dysfunctional.

Family myths are therefore an enmeshed and integrated set of all family members’ personal myths, conjugal myths, and parental myths (Anderson and Bagarozzi 1989; Andolfi et al. 1989a) in addition to cultural myths (Feinstein 1997). Family myths are related to cultural myths since they can be based on or contribute to refining them. Family myths rest on “emotional factors based on the attribution of meanings and use of contents which have particular relevance in the social and religious context to which they belong and which are found in the construction of popular mythologies” (Andolfi et al. 1989a, b, pp. 96–97).

Family businesses do not represent a homogeneous group of organizations since they differ depending on the level of interaction between their constituents, mainly between the family and the business (Labaki et al. 2013). Family business myth composition is therefore dependent upon these interactions. These considerations lead to our first proposition on the conceptualization of family business myths.

-

Proposition 1: Family business myths are multidimensional to different extents, depending on the level of interaction between the family, the business, the individual, and the environment.

Myth Purposes: From Formation to Transformation

The preceding discussion sketched the characteristics of myths in family businesses. The main aspects leading to the creation and transmission of myths inform us about their use or outcomes on the family and business levels.

A historical narrative is more than just the story a manager wants to tell (Foster et al. 2017). The way historical narratives are structured serves a purpose that can differ depending on the target audience. In particular, myths are to be transmitted across generations and are intended for a family business stakeholder audience. Depending on the level of interaction between business and family systems, the outcomes of myths can more predominantly be geared toward the family or the business.

Common purpose of using narrativesin research includes insights into topics such as collective identities, sense-making, legacy, and the dark side of families in business (Hamilton et al. 2017). Different disciplines have emphasized different purposes of myths. We present those that seem particularly relevant to family business, mainly the strategic management and psychotherapy perspectives (Fig 20.2).

Leading the Family Business Strategic Path

As a source of change or continuity with a given state of affairs, the past provides grounds for different strategic orientations (Foster et al. 2017). Organization and strategic management studies have emphasized the potential contribution of history as a strategic resource for both managers and researchers (Foster et al. 2011; Kahl et al. 2012; Kipping and Üsdiken 2009; Lipartito 2014; Suddaby et al. 2010; Wadhwani and Bucheli 2013).

These authors do not consider history as a fixed contextual variable but as a resource. As such, history is not a mere assemblage of facts from the past but bears the capacity to be managed. It does integrate objective and subjective aspects as clearly analyzed in Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983). “Citizens, advertising agencies, antique dealers and politicians, they all construct historical narratives, find value in employing them while modifying them as the years pass by” (Scranton and Fridenson 2013, p. 2). Family and family businesses are of course not immune to such a process.

For most organizations and families, history is a de facto asset, even when not recognized or accounted for in the company’s books. It expresses itself in the form of tangibles—long-standing product or property—and intangibles such as brands, rituals, or shared stories of past events. It integrates real as well as potential liabilities, failures, and villains.

In order to gain commitment from external audiences, history is also used to address perceived expectations and demands placed on the organization by its environment. Scholars argue that it may create inward commitment of employees as well (Zundel et al. 2016). For organization members and executives, there is a strong urge to manage history as much as they manage people, financials, physical assets, patents, or brands to achieve superior performance. Suddaby et al. (2010) framework reveals history as a source of competitive advantage, establishinga link between strategic management and organization theory.

By defining history as a “social and rhetorical construction that can be shaped and manipulated to motivate, persuade and frame action both within and outside an organization”, Suddaby, Foster, and Trank (2010, p. 147) offer a strong foundation to build on. History is not an exogenous variable beyond the control of leaders or members of families, as could be the case of “the past”. History is also not immutable. Its intrinsic plasticity makes it a highly sensitive material in the family context while being a strategic resource. As part of historical narratives, the myths embody the base upon which the family business chooses to engage in certain strategic directions. Given these insights, the following proposition is suggested.

-

Proposition 2: Over the life cycle, myths inform the strategic orientation of the family business and contribute to building its competitive advantage.

Creating and Maintaining Homeostasis of the System

From an anthropological perspective, myths serve to develop and maintain social solidarity and group cohesion (Van der Hart et al. 1989). From a family psychotherapy view, the purpose of family myths is rooted in the family purpose of maintaining homeostasis. They provide a prescription of roles family members are required to play vis-à-vis other family members, as well as ritual formulas for action at times of crisis during its life cycle (Ferreira 1963). Family myths give meaning to the past, define the present, and provide direction for the future (Feinstein 1979). As such, they shape the life paths of individual family members and allow them to take action in critical situations for survival. Whether we move from socio-cultural to organizational, family, or individual myths, they all tend to keep in balance a group of opinions and ideas that are necessary for the survival of the system in which they develop (Andolfi et al. 1989a).

Given these reflections, our next proposition is as follows.

-

Proposition 3: Family business myths contribute to creating and maintaining system homeostasis throughout the life cycle’s critical stages.

Identity Construction and Legitimization

Narrative from the perspective of historians is very central to identity formation. It is a key component of the process of organizational identity construction (Foster et al. 2017; Ravasi and Schultz 2006). The philosopher Paul Ricoeur emphasized the fact that the history of an individual or a community appears as an identity formation when it is told through a narrative (Dowling 2011; Wood 1991). In short, to know oneself (or one’s own history) is to interpret the past. This interpretation could lend to drama or fiction through a narrative in the form of myth. Myths are clues about collective consciousness and personal identity (Thompson 2005).

Vaara and Lamberg (2016) provide an exhaustive summary of the different types and limitations of historical methods used in strategic management. The authors insist on the social construction of history and the use of its narratives as a tool. Several works have looked at narratives to reinforce identity (Zundel et al. 2016) in addition to being legitimization tools within organizations (Landau et al. 2014). In a family business context, the legitimization of succession is one crucial stage. In their study of an Italian family business, Dalpiaz, Tracey, and Phillips (2014) show how next-generation members have strategically used narratives when legitimizing their role as successors. Given these findings, our proposition is as follows.

-

Proposition 4: Family business myths contribute to the construction of the family members’ identity and the legitimization of successors in the family business.

Motivation for Entrepreneurship: Risk-Taking, Resilience, and Innovativeness

Myth is one example of narratives that may influence the entrepreneurial and resiliency behavior of the next generation in family businesses over time. As Jaskiewicz et al. (2015) observe in their empirical study, family narratives motivate and give meaning to entrepreneurship by linking family members to a rich history that defines who they are as a firm and as a family. They also allow the family to view current risks in perspective as compared to relatively more substantial challenges from the past.

Smith (2014) explains how second-generation entrepreneurs create their own identityby means of storytelling. The author suggests that different generations can strategically vary in the focus of their narratives.For example, “second-generation entrepreneur stories are less about overcoming disadvantage than they are about overcoming advantage” (p. 167). By doing so, the next generation can lay ground for their independence and build their own entrepreneurial identity.

Research by Kammerlander et al. (2015) suggests that the focus of stories told in family businesses can impact its innovativeness. Narrativesthat revolve around the founder and create a heroic myth around a single person are negatively related to innovativeness according to this research. In contrast, stories that focus on the family as a collective are positively associated with innovation.

Given these arguments, our proposition is as follows.

-

Proposition 5: Family business myths motivate family entrepreneurship attitudes in terms of risk-taking, resilience, and innovativeness.

Beyond Family Business Myth “Involution”: A Deconstruction or Reconstruction of Myths and Identity

From an anthropological point of view, cultural involution refers to paralyzed cultural conditions, leading to fluidity loss within the system and blockage from further adaptation (Seltzer 1989). Narratives are not static (Suddaby et al. 2010). Rather, they are reconstructions and interpretations that evolve (Barry and Elmes 1997). Despite its characteristics of being resistant over time and often unchallenged by family members, the myth emphasis remains on forward movement (Ahsen 1984).

In particular, family myths are both homeostatic and morphogenic. They contain the necessary components for change (Roberts 1989). When changes occur in social institutions and practices, and the myths which legitimize the previous state of affairs no longer fit, the myths will not disappear because they are flexible (Van Baaren 1984). They will rather be changed, even subtly, in a way that allows them to be maintained. This requires the myth to be adapted to the new situation, armed to deal with a new challenge (Van der Hart et al. 1989).

For the family business to survive in the face of change, it becomes important to overcome the part of rigidity related to the family, individual, organizational, and socio-cultural myths. A much needed, although difficult, endeavor for the family business is to stop being stuck in a certain frame, which could be linked to the identity of its founder, for example. Transforming a myth means to go beyond the existing identity or identities by the affirmation of differences (Perrot 1976).

The case of the family Lego group illustrates how historical narratives are used to promote or facilitate change in organizational identity. The managers’ reinterpretation of the company’s history produced a new, encompassing historical narrative that oriented the company’s strategy with a reconstructed organizational identity (Foster et al. 2017; Schultz and Hernes 2013). This shows the importance of leveraging existing myths to articulate a future view of the family business identity.

Going beyond the stalemated status of cultural involution requires intervention by outsiders, often initiated by revitalization movements or reforms (Turnbull 1987; Wallace 2013). Translating this concept to a family business context leads us to point out the importance of external interventions. The latter could help family businesses in explaining how the identities around the myth were constructed, in order to revise or renegotiate them if needed. As long as the main cultural narrative of the organization remains unchallenged by external pressures, the organization’s cultureshould remain a strong, integrated ideological unit and, thus, a resource for the organization. However, as soon as external parties start questioning the historical narratives of the organization, its culture can become differentiated or fragmented among internal stakeholders. This leads to a cultural shock that requires the emergence of new narratives about the past. This happens through disintegrating and fragmenting past narratives and reworking on re-signifying and repurposing the existing cultural heritage (Foster et al. 2017). Given these insights, our proposition is as follows.

-

Proposition 6: Over the life cycle, family business myths need to be transformed to different extents to ensure the family business continuity.

Discussion

“The myth is timeless in terms of the power it has in influencing human cultures” (Seltzer 1989, p. 23). According to Ferreira (1963) who was the first to link the concept of myth to family processes, the family myth is the focal point that all family processes revolve around (Ferreira 1963). This assertion is of particular relevance for family businesses where the family is the distinctive system as compared to other types of organizations.

This chapter has made initial conceptualization efforts, bridging different fields of study to offer a conceptual framework on narrativeswith a special focus on myths. It outlined the role of myth in shaping the strategic orientation of the business, the identity construction, reconstruction and legitimization, the entrepreneurial attitudes development, as well as the homeostasis of the system in critical stages. This chapter contrasted and integrated literatures and insights from different fields such as business history, management studies, anthropology, and family psychotherapy. By doing so, it offered a unique combination of different perspectives. As the various fields use different theoretical ideas and vocabulary, this overarching outlook provides a basis for discussion to researchers. It therefore can be viewed as a step to more interdisciplinary research between scholars from diverging academic traditions and backgrounds. Furthermore, through our analysis of myths, their roots and consequences, the chapter allows opening up future directions for research that are meant to refine the conceptualization of family business myths toward an empirical development.

Methodological Considerations and Future Research Directions

Stories passed on from generation to generation offer a wealth of information. However, research in management has been largely reluctant to use these stories to a large extent.

Family business scholars suggested that diversity in applied approaches and methods for research can be beneficial to the family business field. Dawson and Hjorth (2012) point toward the possibility of using analytic methods to explore narrative accounts when exploring unique phenomena of family businesses. Relying on stories can offer new insights when it comes to qualitative methods that analyze the way people experience and interpret their life and work situations (Fletcher et al. 2016). Recently, autobiographic works have also been a subject of study (Mathias and Smith 2016). Interviews about stories enable researchers to look beyond the curtain of often emotionally charged and intimate topics that usually remain hidden in other research approaches. Applying such research strategies can therefore enlighten the “why” questions, allowing an intimate connection to empirical realities (Dawson and Hjorth 2012).

Yet, a major shortcoming of using such methods is the abundance of biases in narrative accounts on all levels. First, the situations are usually seen through the lens of the writer or narrator. It is therefore questionable whether the narrative appropriately and accurately represents the situation or whether it is highly biased, even if not linked to a hidden agenda. Second, stories usually capture the narrator’s “sense-making” of the situation. This sense-making is naturally entangled in subjectivity and can be very different from the past situation. It thus falls short due to various individual cognitions such as rationalization processes, motivated reasoning, and hindsight biases.

From the business history perspective, taking myths and stories as a legitimate object of study would certainly open new avenues for research. Historians of mentalities have integrated historical artifacts that do not belong to the material realm for a very long time. Myths told in business families could be a rich source of information about family businesses. In order to achieve this, however, one needs to work onproper historicizing that allows the contextualization not only of the myths’ formation but also their transformation over time. Myths are told for good reasons, and historians might be able to reconnect myths with the context of their formation, transformation, and evolving purposes. They can add their methods of investigation to the conversation using multi-level analysis from a variety of material. Through hermeneutic analysis, historians allow for an iterative process between the data and the historical context in which it was produced. Hermeneutic analysis therefore facilitates an interpretation that is close to the stories’ specificities and environment, and highlights the differences and similarities between meanings conveyed by successive or various versions.

Tackling family business narratives from the angle of myths allows us to focus the object of study by borrowing from methods and evaluation techniques used in family psychotherapy. This would offer an additional understanding of family business narratives.

It is important to bear in mind that, although the past is a rich source of knowledge and experience that can be appropriated and recycled, it can also have a dark side and be a liability (Booth et al. 2007). This is particularly true when we refer to the family’s past several generations back (Böszörményi-Nagy and Spark 1984). It is therefore important for family businesses not to get stuck in their myths but to adapt them to lifecycle changes in a way that addresses the risk of family business cultural involution.

Empirical studies may therefore further explore our propositions by accounting for the heterogeneity of family business archetypes (Labaki et al. 2013) in relation to “healthy” or “unhealthy” myth formation and evolution processes over time. In multigenerational family businesses where a cluster of businesses operate in connection with the family (Michael-Tsabari et al. 2014), it would be interesting to investigate in which type of business (core or peripheral) the myth is mostly prevalent and influential. Furthermore, a lens into the antecedents and outcomes of these myth components across the life cycle would inform us about the resiliency and performance of family businesses in times of crises.

Practical Implications

This chapter points to the importance of family members disrupting long-standing and taken-for-granted myths.It suggests practical implications for the next-generation family members. Understanding one’s own family and business history has been linked to increased self-awareness, practical reflexivity, and self-authorship, all factors that are beneficial for leadership development,complexity management of the family business environment, and the succession process (Barbera et al. 2015).

Exploring mythsand contributing to change can be done through educational or pedagogical tools used by family business educators and advisors. These tools could use interpretation or experiential exercises around the origin and role of myths at different levels of the family business. As such, they can identify different ways to revise, reconsider, or build new myths if needed for family business survival and continuity.

Conclusion

We conclude this chapter inspired by Cecil Maurice Bowra’s quote, “Myths bring the unknown into relation with the known”. Whether we are scholars, practitioners, or family business members, “myths represent for us the mechanism by which we construct reality” (Feinstein and Krippner 1989, p. 111), at least to a certain extent. Business history, family psychotherapy, and management studies are increasingly acknowledging the importance of myths in understanding organizations. Yet, theoretical and empirical works in the family business field are clearly underdeveloped. While we brought together different views in an initial conceptualization effort, our chapter’s research and methodological directions are a clear call to uncover the unknown about family business myths.Implications of future works on family business myths would help business families move through life crises with a renewed and “healthy” mythic perspective.

References

Abrams, L. (2016). Oral history theory. New York: Routledge.

Ahsen, A. (1984). Trojan horse imagery in psychology, art, literature & politics. New York: Brandon House.

Alvesson, M., & Berg, P. O. (1992). Corporate culture and organizational symbolism: An overview (Vol. 34). New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Ancelin Schützenberger, A. (1998). The ancestor syndrome: Transgenerational psychotherapy and the hidden links in the family tree. New York: Routledge.

Anderson, S. A., & Bagarozzi, D. (1989). Family myths: An introduction. In S. A. Anderson & D. Bagarozzi (Eds.), Family myths: Psychotherapy implications (pp. 3–16). New York: The Haworth Press.

Andolfi, M., Angelo, C., & DiNicola, V. F. (1989a). Family myth, metaphor and the metaphoric object in therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy & the Family, 4(3–4), 35–56.

Andolfi, M., Angelo, C., & De Nichilo, M. (1989b). The myth of Atlas: Families and the therapeutic story. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Augé, M. (2004). Oblivion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Barbera, F., Bernhard, F., Nacht, J., & McCann, G. (2015). The relevance of a whole-person learning approach to family business education: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(3), 322–346.

Barry, D., & Elmes, M. (1997). Strategy retold: Toward a narrative view of strategic discourse. Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 429–452.

Becker, E. (1962). The birth and death of meaning: A perspective in psychiatry and anthropology. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. New York: The Free Press.

Booth, C., Clark, P., Delahaye, A., Procter, S., & Rowlinson, M. (2007). Accounting for the dark side of corporate history: Organizational culture perspectives and the Bertelsmann case. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(6), 625–644.

Böszörményi-Nagy, I., & Spark, G. (1984). Invisible loyalties. Levittown: Brunner-Mazel.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice (2004 ed.). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Campbell, J. (1968). The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton: Princeton University.

Colli, A. (2011). Business history in family business studies: From neglect to cooperation? Journal of Family Business Management, 1(1), 14–25.

Colli, A., Howorth, C., & Rose, M. (2013). Long-term perspectives on family business: Editorial. Business History, 55(5–6), 841–854. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fbsh20

Dalpiaz, E., Tracey, P., & Phillips, N. (2014). Succession narratives in family business: The case of Alessi. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(6), 1375–1394.

Dawson, A., & Hjorth, D. (2012). Advancing family business research through narrative analysis. Family Business Review, 25(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511421487.

Dowling, W. C. (2011). Ricoeur on time and narrative. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame.

Eliade, M. (1963). Myth and reality. Translated from the French by Trask, W. R. Planned and Edited by Anshen, R. N. New York: Harper & Row.

Ellwood, R. (1999). The politics of myth: A study of CG Jung, Mircea Eliade, and Joseph Campbell. Albany: SUNY Press.

Evans, R. J. (1997). In defence of history. London: Granta Books.

Feinstein, A. D. (1979). Personal mythology as a paradigm for a holistic public psychology. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 49(2), 198–217.

Feinstein, D. (1997). Personal mythology and psychotherapy: Myth-making in psychological and spiritual development. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(4), 508.

Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1989). Personal myths–in the family way. Journal of Psychotherapy & the Family, 4(3–4), 111–140.

Ferreira, A. J. (1963). Family myth and homeostasis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 9(5), 457.

Fletcher, D., De Massis, A., & Nordqvist, M. (2016). Qualitative research practices and family business scholarship: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(1), 8–25.

Foster, W. M., Suddaby, R., Minkus, A., & Wiebe, E. (2011). History as social memory assets: The example of Tim Hortons. Management & Organizational History, 6(1), 101–120.

Foster, W. M., Coraiola, D. M., Suddaby, R., Kroezen, J., & Chandler, D. (2017). The strategic use of historical narratives: A theoretical framework. Business History, 59(8), 1176–1200.

Gabriel, Y. (2004). Introduction. In Y. Gabriel (Ed.), Myths, stories, and organizations premodern narratives for our times. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J., McCollom Hampton, M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Lifecycles of the family business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hamilton, E., Cruz, A. D., & Jack, S. (2017). Re-framing the status of narrative in family business research: Towards an understanding of families in business. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(1), 3–12.

Hess, R., & Handel, G. (1994). The family as a psychosocial organization. In G. Handel & G. G. Whitchurch (Eds.), The psychosocial interior of the family (4th ed., pp. 3–17). New York: Aldine.

Hjorth, D., & Dawson, A. (2016). The burden of history in the family business organization. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615613375.

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holt, R., & Popp, A. (2013). Emotion, succession, and the family firm: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons. Business History, 55(6), 892–909.

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 29–49.

Johansson, A. W., Li, S.-J., & Tsai, D.-H. (2014). What stories are told from a family business and when? Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, 13(3), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.3917/entre.133.0171.

Kahl, S. J., Silverman, B. S., Cusumano, M. A., Kahl, S. J., Silverman, B. S., & Cusumano, M. A. (2012). The integration of history and strategy research. History and Strategy, Advances in Strategic Management, 29, ix–xxi.

Kammerlander, N., Dessì, C., Bird, M., Floris, M., & Murru, A. (2015). The impact of shared stories on family firm innovation: A multicase study. Family Business Review, 28(4), 332–354.

Kantor, D., & Lehr, W. (1975). Inside the family. New York: Jossey Bass.

Kepner, E. (1983). The family and the firm: A coevolutionary perspective. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 57–70.

Kipping, M., & Üsdiken, B. (2009). Business history and management studies. In G. Jones & J. Zeitlin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of business history (pp. 96–119). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Labaki, R., Michael-Tsabari, N., & Zachary, R. K. (2013). Exploring the emotional Nexus in cogent family business archetypes. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 3(3), 301–330.

Landau, D., Drori, I., & Terjesen, S. (2014). Multiple legitimacy narratives and planned organizational change. Human Relations, 67(11), 1321–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713517403.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1968). Structural Anthropology: Translated from the French by Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. London: Allen Lane/The Penguin Press.

Lipartito, K. (2014). Historical sources and data. In Organizations in time: History, theory, methods (1st ed., pp. 284–304). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lyna, D., & Van Damme, I. (2009). A strategy of seduction? The role of commercial advertisements in the eighteenth-century retailing business of Antwerp. Business History, 51(1), 100–121.

Mathias, B. D., & Smith, A. D. (2016). Autobiographies in organizational research: Using leaders’ life stories in a triangulated research design. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 204–230.

McClendon, R., & Kadis, B. L. (2004). Reconciling relationships and preserving the family business: Tools for success. New York: The Haworth Press.

Michael-Tsabari, N., Labaki, R., & Zachary, R. K. (2014). Toward the cluster model: The family Firm’s entrepreneurial behavior over generations. Family Business Review, 27(2), 161–185.

Mordhorst, M., & Schwarzkopf, S. (2017). Theorising narrative in business history. Business History, 59, 1–21.

Ochs, E., & Taylor, C. (1992). Family narrative as political activity. Discourse & Society, 3(3), 301–340.

Perrot, J. (1976). Mythe et littérature sous le signe des jumeaux (Vol. 8). Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Pieper, T. M., & Klein, S. B. (2007). The Bulleye: A systems approach to modeling family firms. Family Business Review, 20(4), 301–319.

Popp, A. (2015). Entrepreneurial families: Business, marriage and life in the early nineteenth century. London: Routledge.

Ravasi, D., & Schultz, M. (2006). Responding to organizational identity threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 433–458.

Ricœur, P. (1984). Time and narrative. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roberts, J. (1989). Mythmaking in the land of imperfect specialness: Lions, laundry baskets and cognitive deficits. Journal of Psychotherapy & the Family, 4(3–4), 81–110.

Rosenblatt, P., De Mik, L., Anderson, R. M., & Johnson, P. A. (1985). The family in business: Understanding and dealing with the challenges entrepreneurial families face. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schultz, M., & Hernes, T. (2013). A temporal perspective on organizational identity. Organization Science, 24(1), 1–21.

Schwartz, H. S. (1985). The usefulness of myth and the myth of usefulness: A dilemma for the applied organizational scientist. Journal of Management, 11(1), 31.

Scranton, P., & Fridenson, P. (2013). Reimagining business history. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Seltzer, W. J. (1989). Myths of destruction: A cultural approach to families in therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy & the Family, 4(3–4), 17–34.

Smith, R. (2014). Authoring second-generation entrepreneur and family business stories. Journal of family business management, 4(2), 149–170.

Smith, R. (2017). Reading liminal and temporal dimensionality in the Baxter family ‘public-narrative’. International Small Business Journal, First published online, March, 10, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617698033.

Strati, A. (1998). Organizational symbolism as a social construction: A perspective from the sociology of knowledge. Human Relations, 51(11), 1379–1402.

Suddaby, R., Foster, W. M., & Trank, C. Q. (2010). Rhetorical history as a source of competitive advantage. Advances in Strategic Management, 27, 147–173.

Summerfield, P. (2004). Culture and composure: Creating narratives of the gendered self in oral history interviews. Cultural and Social History, 1(1), 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478003804cs0005oa.

Thompson, P. (2005). Family myths, models and denials in the shaping of individual life paths. In D. Bertaux & P. Thompson (Eds.), Between generations: Family models, myths & memories (pp. 13–38). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Turnbull, C. (1987). Mountain people. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Vaara, E., & Lamberg, J.-A. (2016). Taking historical embeddedness seriously: Three historical approaches to advance strategy process and practice research. Academy of Management Review, 41(4), 633–657. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0172.

Van Baaren, T. P. (1984). The flexibility of myth. In Sacred Narrative: readings in the theory of myth (pp. 217–224). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Van der Hart, O., Witztum, E., & de Voogt, A. (1989). Myths and rituals: Anthropological views and their application in strategic family therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy & the Family, 4(3–4), 57–80.

Varje, P., Anttila, E., & Väänänen, A. (2013). Emergence of emotional management: Changing manager ideals in Finnish job advertisements from 1949 to 2009. Management & Organizational History, 8(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2013.804416.

Wadhwani, R. D., & Bucheli, M. (2013). The future of the past in management and organizational studies. SSRN, 2271752.

Wallace, A. (2013). Religion: An anthropological view. New York: Random House.

White, H. (1978). Historical text as literary artifact in the writing of history: Literature form and historical understanding. In Tropics of discourse – essays in cultural criticism (pp. 81–100). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

White, H. (2002). The historical text as literary artifact. In Narrative dynamics: Essays on time, plot, closure, and frames (pp. 191–210). Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Wood, D. (Ed.). (1991). On Paul Ricoeur: Narrative and interpretation. London/New York: Routledge.

Zundel, M., Holt, R., & Popp, A. (2016). Using history in the creation of organizational identity. Management & Organizational History, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2015.1124042.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Labaki, R., Bernhard, F., Cailluet, L. (2019). The Strategic Use of Historical Narratives in the Family Business. In: Memili, E., Dibrell, C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity among Family Firms. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-77675-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-77676-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)