Abstract

Much of the existing research on educational outcomes among immigrant-origin children has been conducted in “old” immigrant-receiving countries. This chapter focuses instead on how immigrant-origin children and youth fare in a country, the Republic of Ireland, where large-scale immigration is a more recent phenomenon. What makes this case of particular interest is the fact that the immigrant population in Ireland is highly heterogeneous and has, on average, high levels of educational attainment. This chapter focuses on the academic achievement of immigrant-origin young people in Irish secondary schools, drawing on the latest round of PISA data as well as on data from a large-scale child cohort study, the Growing Up in Ireland study. The analyses point to an achievement gap in relation to literacy test scores but more variable findings in relation to Math and Science. Language of origin rather than immigrant status per se emerges as one of the main drivers of this achievement gap. The chapter concludes by highlighting the lack of consistent information on educational outcomes among immigrant-origin young people and argues for on-going monitoring of such outcomes in order to prevent longer term difficulties in integration.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

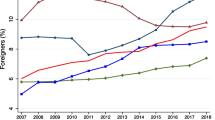

The economic boom, otherwise known as “the Celtic Tiger”, which took place in Ireland from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s prompted rapid and large-scale immigration, transforming Ireland from a country of emigration to a “new immigrant-receiving country.” The flow of immigrants into Ireland was modest before this period of economic prosperity, averaging only 800 persons annually (Central Statistics Office [CSO], 2012a, 2012b), but it grew substantially in the following years. In 2002, the number of non-Irish individuals living in Ireland stood at 224,261 but the following Census (2006) saw the figures grow to 419,733, with a further increase to 544,357 by 2011 (CSO, interactive tables). There was some decrease in the rate of flow of immigrants during the recession but non-Irish nationals still made up 11.6% of the population in 2016, down marginally from 12.2% in 2011 (CSO, 2017). The number of asylum seekers showed a similar trend, with increases during the boom years, peaking in 2002 and declining significantly over the course of the recession (Quinn & Kingston, 2012; ORAC, 2017).

Compared to the native population, immigrants to Ireland are highly educated, with a higher proportion having tertiary education compared to the native Irish (Darmody, McGinnity, & Kingston, 2016; Röder, Ward, Frese, & Sánchez, 2014). However, despite their high levels of educational attainment, existing research finds that immigrants to Ireland fare less well than Irish nationals in the labour market across a range of dimensions, including access to higher paid and higher status jobs, experience of discrimination at work, and levels of unemployment (Barrett, McGinnity, & Quinn, 2017; McGinnity & Lunn, 2011; O’Connell & McGinnity, 2008;). In addition, Barrett and Kelly (2012) found no evidence to suggest that this occupational gap became smaller as immigrants spent longer time in Ireland. Some groups of immigrants seem to fare less well compared to others. For example, the highest unemployment rate has been found among adults from outside the European Union (EU) (Watson, Lunn, Quinn, & Russell, 2011).

A further distinctive feature of the immigrant population in Ireland is its heterogeneity in terms of country of origin, language proficiency and legal status. The immigrant population is drawn from 180 countries, with the largest national groups being from Poland, the U.K. and Lithuania (CSO, 2017). This diversity may hinder the development of ethnic enclaves in the Irish context. Over two-thirds (68%) of the immigrant population speak a language other than English (or Irish) at home (CSO, 2017). The Census of Population also provides information on (self-reported) ability to speak English.Footnote 1 Over half (55%) of those who speak a language other than English report that they speak English ‘very well.’ English language proficiency varies significantly by length of time living in Ireland and national origin (CSO, 2017). In addition to differences in language and nationality of origin, the immigrant group also varies in their legal status. EU nationals are free to live and work in Ireland but non-EU groups must enter the country on the basis of an employment or student visa or as an asylum seeker or programme refugee. Thus the immigrant population in Ireland differs along the dimensions of nationality, English language proficiency and legal status, factors that are likely to shape their experiences of the educational system.

The educational outcomes of immigrant-origin children and young people are considered in the next section. Since immigration to Ireland has been a recent phenomenon, the children and young people being discussed are largely, but not wholly, first-generation immigrants. Due to the small number of second-generation immigrants, first- and second-generation immigrants are generally grouped together into one ‘immigrant origin’ group (though PISA data distinguish between the two groups). The analyses focus on immigrant-origin students in secondary schools, while placing these findings in the context of achievement levels earlier in the school system.

Educational Outcomes of Immigrant Children

According to student data collected by the Department of Education and Skills for the 2015–2016 academic year, children and young people born outside Ireland made up 11% of the student body in mainstream secondary education, with most of this group coming from other European Union countries (see Table 8.1).

The availability of information on the academic outcomes of immigrant children and young people in Ireland is quite sparse. Ireland has participated in the TIMSS and PISA studies so cross-nationally comparable information on achievement test scores is available for some cohorts of young people. In addition, the Growing Up in Ireland Footnote 2 study provides detailed information on (to date) test scores at 5, 9, and 13 years of age as well as on other outcomes such as educational aspirations among a large national sample that includes both immigrant and native Irish children. However, there is currently no information available on differences in the achievement levels of Irish and immigrant-origin students in the State exams conducted at the end of lower and upper secondary education. This lacuna is particularly important given the influential role of upper secondary exam grades in ensuring access to higher education and good quality employment. The Department of Education and Skills (DES) carries out regular estimates of school retention but immigrant-origin students cannot be distinguished in these analyses. However, national data for 20–24 year olds suggest that rates of early school leaving are roughly comparable for immigrants and Irish young people (Barrett et al., 2017). Another gap relates to information on post-school transitions. While the domicile of origin of entrants to higher education is recorded, it is not possible to distinguish those who were foreign-born (or whose parents are foreign-born) and are domiciled in Ireland. In order to ensure that immigrant-origin students can reach their full potential in the Irish educational system, it is important to be able to monitor their outcomes, as well as their distribution across different kinds of schools.

International research points to immigrants being a positively selected group, a phenomenon which explains, at least in part, relatively high educational expectations among immigrant groups (Feliciano, 2005). In the Irish context too, immigrant parents tend to hold high educational expectations and aspirations for their children. The analysis of Growing Up in Ireland data collected on 9-year-old children in Ireland shows that, as with Irish mothers, the majority of mothers with immigrant backgrounds across all national groups expect their child to go on to tertiary education and expectations among some mothers, especially from Africa and Asia, are somewhat higher than those of Irish mothers (McGinnity, Darmody, & Murray, 2015). Furthermore, immigrant-origin children are generally perceived by school teachers and principals as highly motivated, in some cases seen as “model students” (Smyth, Darmody, McGinnity, & Byrne, 2009).

While immigrant parents and their children may have high aspirations regarding educational pathways, one needs to consider how they fare academically in order to assess how realistic these expectations are. Proficiency in the language of instruction is an important factor enabling immigrant-origin children to access the curriculum and participate in classroom activities. English—the language of instruction in the vast majority of Irish schools—is a mother tongue to only a minority of immigrant students (see above). In the following discussion, we therefore discuss the role of both immigrant background and language spoken in influencing achievement levels.

Drawing on PISA 2015 data,Footnote 3 the initial analysis explores differences between native, first-generation and second-generationFootnote 4 immigrantsFootnote 5 in their performance in standardized tests (mean scores in Mathematics, Science, and Reading skills). At 15 years of age, first-generation immigrant students achieve significantly lower test scores in Mathematics and Reading than their native Irish peers, with a bigger achievement gap for Reading than for Mathematics (see Table 8.2). The small number of second-generation students do not differ from native Irish students in their test scores. Science test scores do not vary significantly by immigrant background, though scores for native Irish students are slightly higher than those found among first- and second-generation immigrant students. As expected, the results vary by language spoken (see Table 8.2), with immigrant-origin youth speaking a language other than English achieving significantly lower scores in Reading than English-speaking immigrants (499.70 vs. 522.84). The pattern is similar, although the gap is somewhat smaller, for Mathematics (493.61 vs. 503.40) and Science (492.94 vs. 507.85). It is worth noting that the gap in test scores on the basis of language among immigrants is larger than the gap between immigrants as a group and the native Irish, highlighting the importance of taking account of the heterogeneity of the immigrant population in Ireland.

In order to gain a more complete picture of the academic achievement levels of immigrant-origin youth, it is useful to explore how they fare academically earlier in their educational career. In doing so, the rest of the chapter draws on data from three waves of the Growing Up in Ireland national longitudinal study, relating to the wave at 5 years of age for the infant cohort and 9 and 13 years of age for the child cohort.Footnote 6 At the age of 5 years, children took the naming vocabulary and picture similarities subscales of the British Ability Scale. Significant differences are evident between immigrant-originFootnote 7 and native children in the naming vocabulary test results (45.75 vs. 56.65) (Table 8.3). Proficiency in the language of instruction is what matters. Among immigrants, children whose first language is English performed better in the naming vocabulary test compared to their non-English speaking counterparts (52.49 vs. 37.06). For the picture similarities test, which was designed to test non-verbal skills, results did not vary between native and immigrant children. Within the immigrant group, however, there was a significant but very small difference in test scores in favour of those from non-English-speaking backgrounds (58.56 vs. 57.98).

Turning to the 9 year olds, children were administered the standardised Drumcondra tests in reading and mathematics; these tests are commonly used in the Irish primary school system to assess children’s achievement relative to that of their peers and the tests are based on the material covered in the national curriculum. The test scores were scaled to have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. In reading, the mean test score was significantly lower among immigrant-origin children compared to their Irish counterparts (98.46 vs. 102.66; almost a third of a standard deviation) (Table 8.4). As with the 5 year olds, language spoken in the home was a key driver of these patterns, with much lower test scores among those from a non-English-speaking background (99.19 for English-speakers; 92.9 for non-English speakers). Thus non-English-speaking children score almost half a standard deviation below their English-speaking peers in reading. The analysis showed a small but statistically significant difference between immigrant-origin and native students in the mathematics test (88.92 vs. 90.51) but differences in maths performance did not differ by language background among the immigrant group. Given the heterogeneity of the immigrant group, it is important to take account of these between-group differences (Molcho, Kelly, & Nic Gabhainn, 2009). Previous research on immigrant achievement in the Irish context using the same GUI data has differentiated by country of origin, showing that the lowest levels of reading achievement among 9 year olds are found among children of Eastern European origin (McGinnity et al., 2015). In contrast, children whose mothers are from the U.K. or Western Europe resemble Irish children in their reading performance. In mathematics, the lowest scores are found among children of African origin, a pattern that is accounted for by their greater levels of financial strain.

The children tested at the age of 9 were tested again at the age of 13. This time, the tests used were not based on the curriculum but rather reflected aptitude in verbal and numerical reasoning. As with test scores at age 9, scores were scaled to have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The comparison of mean scores in verbal reasoning showed significant differences between immigrant and non-immigrant students, with the former having lower scores (97.71 vs. 99.98) (Table 8.5). The differences between groups in numeric ability were minor and not statistically significant. However, when proficiency in English is taken into consideration, students from families in which English is spoken in the home performed significantly better compared to students from families with a different dominant language (98.51 vs. 93.51, a difference of a third of a standard deviation). For numerical reasoning, the reverse pattern was found, with slightly but significantly higher scores among non-English speakers (101.62 vs. 98.59).

While immigrant-origin students are generally seen as highly motivated and ambitious (Smyth et al., 2009), poor proficiency in the language of instruction may impair the academic success of even the most motivated and ambitious student, especially in a context where the majority of secondary school subjects require advanced fluency in English. While the overall differences between Irish and immigrant children in achievement in English reading and mathematics are relatively modest, they may lead to cumulative disadvantage as children move through the educational system (Darmody, Byrne, & McGinnity, 2012).

Understanding the Educational Outcomes of Immigrant Children

This section looks for explanations for the patterns found in the previous section by drawing on existing Irish research on immigrant children and young people. Education is a crucial pathway for upward mobility for all groups, but particularly for immigrants as many of these families may have experienced labour market penalties when migrating, with existing research showing that many new arrivals are working in occupations below their skill level (O’Connell & McGinnity, 2008). Despite having parents with high levels of educational attainment who show high aspirations for their children (Darmody et al., 2016), many underperform academically compared to their native-born counterparts (see above; McGinnity et al., 2015). In other countries, differences in outcomes can be attributed to lower educational resources among immigrant families but, as discussed above, immigrants in Ireland tend to be highly qualified (O’Connell & McGinnity, 2008). Language emerges as the main driver of achievement differences for children of immigrant origin in Ireland (see above) and poorer language proficiency can serve to further reinforce differences; for example, if immigrant children do not participate in the kinds of out-of-school activities which contribute to their in-school learning (Devine, 2009; Smyth, 2016). Some groups, particularly those of African origin, may also have poorer levels of economic resources because they came to Ireland as asylum seekers (Darmody et al., 2016; McGinnity et al., 2015).

School factors have been found to influence the academic careers of immigrant-origin children in Ireland. A distinctive feature of the educational landscape in Ireland is the extent of active school choice, especially at secondary level. Thus, around half of the student cohort do not attend their nearest or most accessible secondary schools and families make very active choices about where to send their children to school. On the other side of the equation, if schools are over-subscribed (that is, have more applicants than places) they can use a range of criteria for deciding which students to select. These criteria include being on a waiting list, a parent or older sibling having attended the school, and, in many religious schools, being of the specified religion. These criteria are likely to have a particular effect on the options open to those newly arrived in the country.

The first comprehensive study on the experiences of immigrant-origin children and youth in Irish primary and secondary schools was conducted in 2007–2008 (see Smyth et al., 2009). This study found that most secondary schools in Ireland recorded having at least some immigrant-origin students. In contrast, primary schools were more polarized, with smaller rural schools typically having no immigrant students while certain urban schools had much higher concentrations of immigrant pupils. This pattern of differentiation by immigrant background can be further reinforced by the movement of the immigrant population to specific urban areas (Devine, 2011b, 2013a, 2013b). Immigrant children and young people were found to be more likely to be concentrated in schools serving socio-economically disadvantaged populations since immigrant families find it difficult to gain access to oversubscribed schools and thus need to take up places in schools with free capacity, many such schools catering to more deprived populations in urban areas (Byrne, McGinnity, Smyth, & Darmody, 2010). This pattern may have a negative influence on these students’ academic outcomes, since research points to a gap in educational outcomes between socially deprived schools and other schools (Smyth, McCoy, & Kingston, 2015). More recent information (see Duncan, 2015; Houses of the Oireachtas, 2015) indicates that immigrant-origin children continue to be concentrated in some primary schools, some of which cater to a student population where the majority are of immigrant origin.

Teachers play a crucial role in the educational experiences of children. While the student body in Ireland has become more diverse over time, this is not reflected in the profile of teachers in Irish primary and secondary schools who are mostly white and middle class (Darmody & Smyth, 2016; Heinz, 2013; Keane & Heinz, 2015, 2016; Parker-Jenkins & Masterson, 2013). Native-origin teachers may serve to transmit dominant cultural norms, whereby minority cultural and social capital often becomes misrecognized and undervalued (Darmody, Smyth, Byrne, & McGinnity, 2011; Devine, 2005; Kitching, 2010, 2011). Some teachers lack knowledge of the background of immigrant-origin children in their class (Devine, 2011a), indicating a limited focus on diversity in initial teacher education programmes (Ní Laoire, Bushin, Carpena-Méndez, & White, 2009). Existing research also alludes to the racialised distribution of learner “ability,” whereby some immigrant groups of students are perceived as less able (Kitching, 2014). Being seen as different by teachers (and native peers) is likely to reproduce negative attitudes toward immigrant and other more vulnerable children, normalizing their underachievement and seeing them in deficit terms (Devine, 2013a, 2013b).

While the role of a teacher is important for the school experiences of children, especially at younger ages, culturally responsive leadership is important in order to value all children equally (Devine, 2013a), as is a whole-school approach to supporting immigrant-origin students (Devine, 2011a, 2011b). Previous research has recognized the role of the school as an important site for learning respect for, and recognition of, other groups providing formal and informal opportunities for interaction (Darmody & Smyth, 2015; Smyth et al., 2009). Interaction of this kind is likely to foster not only social integration but also enhance student learning.

In contrast to the experience in several other countries where immigrant-origin young people report higher levels of disaffection from school, immigrant-origin children and young people in Ireland seem to resemble their native peers in their attitudes to school and their teachers (Smyth, 2017). As mentioned above, there is a lack of systematic research on achievement in State exams by immigrant status. However, a small-scale study by Ledwith and Reilly (2013) suggests that, at least in one urban area, immigrant students were significantly less likely to take higher level subjects in their lower secondary (Junior Certificate) examinations compared to their native peers, even controlling for differences in language fluency, gender and the socio-economic status of the school population. If this pattern is found more widely, it would represent a significant barrier to immigrant young people taking more advanced subjects at upper secondary level and beyond.

The academic achievement gap observed between immigrant children and their Irish peers is likely to have long-term implications for their future well-being. The role of educational policy in shaping outcomes for immigrant children and young people is discussed in greater detail below.

Education Policies for Children with a Migration Background

Over the last two decades, Irish primary and secondary schools have become increasingly culturally and linguistically diverse, raising policy challenges for dealing with a more heterogeneous student population (Smyth et al., 2009). This section begins by discussing the implications of the structure of the Irish educational system for immigrant groups before examining specific policies adopted to support these groups.

As discussed above, the interaction of parental choice of school and school admissions policies means that schools in Ireland differ in their social profile (Smyth et al., 2015). Newly arrived immigrant families have experienced difficulties in accessing more popular schools and, as a result, have been over-represented in school serving socio-economically disadvantaged populations (Smyth et al., 2009). In recognition of the way in which school admissions criteria can exclude certain groups, including children of immigrant origin, the Education (Admission to Schools) Bill was published in 2016. At the time of writing, this bill has not yet passed into law but is intended to introduce greater transparency in school enrolment policies and to abolish the use of waiting lists. This policy move is likely to have particular implications for newly arrived immigrant families by enhancing their chances of accessing a wider range of schools.

A further distinctive feature of the Irish system is the role of religion in schooling. The vast majority of primary schools are religious in character, mainly Roman Catholic, with only 4% of schools adopting a non-denominational or multi-faith approach. All religious schools provide faith formation classes. Parents have the right to opt out of these classes on behalf of their children but these children commonly remain in the class doing other schoolwork (Smyth et al., 2009). At the secondary level, around half of the schools are voluntary secondary schools generally run by a religious order or religious trust body. Schools have the right to give preference to children of their specific religious faith in their admissions policy. The issue of religion is not being addressed in new legislation around school admissions but, at the time of writing, the Department for Education and Skills is conducting a consultation process around the appropriate place of religion in school admissions.

Children and young people of immigrant origin are diverse in terms of their religious beliefs but a higher proportion are non-Catholic than among the native Irish population (CSO, 2017). The religious profile of schools therefore has significant implications for the ability of immigrant families to select schools which align with their religious or moral beliefs. Furthermore, opting out of religious education class can serve as a further signal of difference (Smyth, Lyons, & Darmody, 2012), which may negatively impact on the social integration of immigrant-origin children.

Specific policies to enhance the educational experiences of immigrant-origin children and young people fall into two main categories: intercultural guidelines and supports for English language acquisition. The National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2005, 2006) has compiled and disseminated guidelines for intercultural education for primary and secondary schools. This emphasis on creating an intercultural learning environment was further reinforced by the government’s Intercultural Education Strategy 2010–2015. This strategy document endeavours to ensure that all students experience an education that “respects the diversity of values, beliefs, languages and traditions in Irish society and is conducted in a spirit of partnership” and that “all education providers are assisted with ensuring that inclusion and integration within an intercultural learning environment become the norm” (Department of Education and Skills [DES] & Office of the Minister for Integration [OMI], 2010, Executive Summary section, para. 1). It is not known, however, the extent to which school principals and teachers implement the approaches described in these documents. In relation to teacher education, initial teacher education in diversity is not compulsory in Ireland, with intercultural modules compulsory in some colleges of education and not in others. Recent years have seen the introduction of some continuous professional development courses on intercultural education and related issues, including training for language support teachers.

Additional educational resources for pupils who are learning English as an additional language (EAL) are the main form of targeted support for immigrant-origin children and young people in primary and secondary schools (Faas, Sokolowska, & Darmody, 2015; Smyth et al., 2009; Taguma, Kim, Wurzburg, & Kelly, 2009). The Department of Education and Skills (2012a, 2012b) has identified examples of good practice across schools in supporting EAL students. However, both evaluations found scope for more effective differentiation of class programmes and lessons for EAL pupils and the need for closer collaboration between mainstream class teachers and EAL support teachers. At the secondary level, the evaluations suggest the need for a broader acceptance that every subject teacher is also a language teacher. Across both levels, the reports identify a need to provide further professional development opportunities for teachers. The nature of support allocation has since been changed, with primary schools now receiving resources to cover both learning support (for students with special educational needs) and language support. Autonomy is given to schools to deploy these teaching hours between learning and language support depending on their specific needs. A similar process of combining the allocation of learning and language support has been adopted at the secondary level. This reform makes it more difficult to assess the amount of resources allocated to immigrant-origin children and young people. Survey data indicate that 2.3% of second class (8-year old) students and 2% of 6th-class (12-year old) students are in receipt of language support for English (Kavanagh, Sheil, Gilleece, & Kiniry, 2016). This is lower than the overall numbers of immigrant-origin students who speak a language other than English at home; however, there are no available data on the extent to which language provision meets the needs of these students.

Overall, the lack of data on the educational outcomes of immigrant-origin children and young people makes it difficult to assess the impact of educational policies in Ireland. In particular, the extent to which resources are being devoted to language support at the school level and whether schools are adopting a genuinely intercultural approach in their day-to-day teaching are not known.

Conclusion

This chapter has discussed the academic achievement of immigrant-origin children and young people in Ireland. Empirical studies indicate that immigrant students are disadvantaged in most educational systems, but also that their outcomes vary between countries and within groups. Ireland is a particularly interesting case among other Western countries, given the relatively recent history of immigration, the heterogeneity of the immigrant population in terms of country of origin, linguistic, and religious backgrounds, and high levels of educational attainment among adult immigrants.

Rapid large-scale immigration to Ireland has meant that the country has had to move quickly in order to address the needs of these new arrivals. This resulted in a somewhat reactive rather than proactive approach to policy-making, with initial efforts focused on providing language supports for newly arrived children and young people. Greater attention to broader issues of inclusion, especially the need to promote intercultural education, has developed over time. Analyses in the chapter have highlighted the significant impact of language proficiency on the academic achievement of immigrant-origin students. However, changes in the allocation of resources to schools means that it is not possible to identify the extent to which language needs among immigrant-origin children are currently being met. The chapter has pointed to other lacunae in data availability, with no information available on State examination results among immigrant-origin young people. Such empirical evidence is vital in order to prevent the emergence of potential differentiation in educational outcomes in the longer term. In its absence, there is a risk that children and young people of immigrant origin will become invisible within the educational system.

The nature of the Irish educational system, specifically its religious character and the degree of school choice, has significant implications for the inclusion of immigrant-origin children and young people. It is hoped that new policy developments, including changes in the school admissions criteria and the types of schools available, will make access to education more transparent and equitable to all families and their children. However, the debate about the role of religion in schooling is likely to take longer to resolve, posing challenges for some groups of immigrant families in locating a school that reflects their religious or moral belief systems.

Notes

- 1.

Those who spoke language other than English or Irish were asked to assess their ability to speak English. The categories include “very well,” “well,” “not well,” and “not at all.”

- 2.

Growing Up in Ireland is a government-funded national longitudinal study of children, carried out by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and Trinity College Dublin (TCD). For more information see: http://www.esri.ie/growing-up-in-ireland/

- 3.

In 2015, 167 secondary schools in Ireland took part in PISA. After exemptions, refusals, and absences were taken into account, 5741 students completed the assessment. In Ireland, Third Year students account for 60.5% of students in PISA 2015, Transition Year students for 26.7%, Fifth Year students for 10.9%, and Second Year students for 1.9% (Shiel, Kelleher, McKeown, & Denner, 2016).

- 4.

The number of 15-year-old second-generation students is relatively small in Ireland because of the recency of large-scale immigration (n = 179 or 3%; first-generation n = 581 or 11%).

- 5.

OECD categorizes a student as having an “immigrant” background if the student was born in the test country and both parents were born elsewhere, or if the student and parents were born outside the test country; this chapter defines “immigrants” as those children with neither parent born in Ireland.

- 6.

The survey of 5 year olds and their families was conducted in 2013 while data collection at 9 and 13 years of age were conducted in 2007/8 and 2011/12.

- 7.

In the GUI analyses, children are defined as “immigrant” if both parents are born outside Ireland, or in case of a lone parent, the parent is born outside Ireland.

References

Barrett, A., & Kelly, E. (2012). The impact of Ireland’s recession on the labour market outcomes of its immigrants. European Journal of Population, 28(1), 91–111.

Barrett, A., McGinnity, F., & Quinn, E. (Eds.). (2017). Monitoring report on integration. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

Byrne, D., McGinnity, F., Smyth, E., & Darmody, M. (2010). Immigration and school composition in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 29(3), 271–288.

Central Statistics Office. (2012a). Census 2011—Profile 6: Migration and diversity. Retrieved from http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/census2011profile6/Profile_6_Migration_and_Diversity_entire_doc.pdf

Central Statistics Office. (2012b). Population and migration estimates: April 2012. Dublin, Ireland: Central Statistics Office.

Central Statistics Office. (2017). Census 2016 summary results. Dublin, Ireland: Central Statistics Office.

Darmody, M., Byrne, D., & McGinnity, F. (2012). Cumulative disadvantage? Educational careers of migrant students in Irish secondary schools. Race Ethnicity Education, 17(1), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.674021

Darmody, M., McGinnity, F., & Kingston, G. (2016). The experiences of migrant children in Ireland. In J. Williams, E. Nixon, E. Smyth, & D. Watson (Eds.), Cherishing all the children equally? Ireland 100 years on from the Easter Rising (pp. 175–193). Dublin, Ireland: Oak Tree Press.

Darmody, M., & Smyth, E. (2015). ‘When you actually talk to them…’ – Recognising and respecting cultural and religious diversity in Irish schools’. In I. Honohan & N. Rougier (Eds.), Tolerance in Ireland, north and south. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Darmody, M., & Smyth, E. (2016). Entry criteria into initial teacher education in Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., Byrne, D., & McGinnity, F. (2011). New school, new system: The experiences of immigrant students in Irish schools. In Z. Bekerman & T. Geisen (Eds.), International handbook of migration, minorities and education: Understanding cultural and social differences in processes of learning (pp. 283–299). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Department of Education and Skills. (2012a). English as an additional language in primary schools in 2008. Retrieved from https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/EAL-in-Primary-Schools.pdf

Department of Education and Skills. (2012b). Looking at English as an additional language: Teaching and learning in post-primary schools in 2008. Retrieved from https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/Looking-at-EAL-Post-Primary-Schools-.pdf

Department of Education and Skills, and Office of the Minister for Integration. (2010). Intercultural education strategy, 2010–2015. Retrieved from https://www.into.ie/ROI/Publications/OtherPublications/OtherPublicationsDownloads/Intercultural_education_strategy.pdf

Devine, D. (2005). Welcome to the Celtic Tiger? Teacher responses to immigration and increasing ethnic diversity in Irish schools. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 15(1), 49–70.

Devine, D. (2009). Mobilising capitals? Migrant children’s negotiation of their everyday lives in school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30(5), 521–535.

Devine, D. (2011a). Immigration and schooling in the Republic of Ireland. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Devine, D. (2011b). Securing migrant children’s educational well-being: perspective of policy and practice in Irish schools. In M. Darmody, N. Tyrrell, & S. Song (Eds.), The changing faces of Ireland: exploring the lives of immigrant and ethnic minority children (pp. 73–88). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

Devine, D. (2013a). Practicing leadership in newly multi-ethnic schools: Tensions in the field? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(3), 392–411.

Devine, D. (2013b). Valuing children differently? Migrant children in education. Children & Society, 27(4), 282–294.

Duncan, P. (2015, October 1). School admission policies have led to segregation—principal. The Irish Times. Retrieved from http://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/school-admission-policies-have-led-to-segregation-principal-1.2374620

Faas, D., Sokolowska, B., & Darmody, M. (2015). “Everybody is available to them”: Support measures for migrant students in Irish secondary schools. British Journal of Educational Studies, 63(4), 447–466.

Feliciano, C. (2005). Unequal origins: Immigrant selection and the education of the second generation. Texas: Lfb Scholarly Pub Llc.

Heinz, M. (2013). The next generation of teachers: An investigation of second-level student teachers’ backgrounds in the Republic of Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 32(2), 139–156.

Houses of the Oireachtas. (2015). Choosing segregation? The implications of school choice. Spotlight, 1. Retrieved from http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/housesoftheoireachtas/libraryresearch/spotlights/SpotlightSchoolchoice290915_101712.pdf

Kavanagh, L., Sheil, G., Gilleece, L., & Kiniry, J. (2016). The 2014 national assessments of English reading and mathematics. Volume II: Context report. Dublin, Ireland: Educational Research Centre.

Keane, E., & Heinz, M. (2015). Diversity in initial teacher education in Ireland: The socio-demographic backgrounds of postgraduate post-primary entrants in 2013 and 2014. Irish Educational Studies, 34(3), 281–301.

Keane, E., & Heinz, M. (2016). Excavating an injustice? Nationality/ies, ethnicity/ies and experiences with diversity of initial teacher education applicants and entrants in Ireland in 2014. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 507–527.

Kitching, K. (2010). An excavation of the racialised politics of viability underpinning education policy in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 29(3), 213–229.

Kitching, K. (2011). Interrogating the changing inequalities constituting “popular” “deviant” and “ordinary” subjects of school/subculture in Ireland: Moments of new migrant student recognition, resistance and recuperation. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 14(3), 293–311.

Kitching, K. (2014). The politics of compulsive education: Racism and learner-citizenship. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ledwith, V., & Reilly, K. (2013). Two tiers emerging? School choice and educational achievement disparities among young migrants and non-migrants in Galway City and urban fringe. Population, Space and Place, 19(1), 46–59.

McGinnity, F., Darmody, M., & Murray, A. (2015). Academic achievement among immigrant children in Irish primary schools. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

McGinnity, F., & Lunn, R. D. (2011). Measuring discrimination facing ethnic minority job applicants: An Irish experiment. Work, Employment and Society, 25(4), 693–708.

Molcho, M., Kelly, C., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (2009). Deficits in health and wellbeing among immigrant children in Ireland: The explanatory role of social capital. Translocations: Migration and Social Change. Retrieved from http://www.nuigalway.ie/hbsc/documents/molcho__translocations.pdf

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. (2005). Guidelines for schools: Intercultural education in the primary school. Retrieved from http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/Publications/Intercultural.pdf

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. (2006). Guidelines for schools: Intercultural education in the post-primary school. Retrieved from http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/publications/Interc%20Guide_Eng.pdf

Ní Laoire, C., Bushin, N., Carpena-Méndez, N., & White, A. (2009). Tell me about yourself: Migrant children’s experiences of moving to and living in Ireland. Cork, Ireland: University College Cork.

O’Connell, P., & McGinnity, F. (2008). Immigrants at work: Ethnicity and nationality in the Irish labour market. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

ORAC. (2017). Summary of key developments in 2016. Dublin, Ireland: ORAC.

Parker-Jenkins, M., & Masterson, M. (2013). No longer “Catholic, White and Gaelic”: Schools in Ireland coming to terms with cultural diversity. Journal Irish Educational Studies, 32(4), 477–492.

Quinn, E., & Kingston, G. (2012). Practical measures for reducing irregular migration: Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

Röder, A., Ward, M., Frese, C., & Sánchez, E. (2014). New Irish families: A profile of second generation children and their families. Dublin, Ireland: Trinity College Dublin.

Shiel, G., Kelleher, C., McKeown, C., & Denner, S. (2016). Future ready? The performance of 15-year-olds in Ireland on science, reading literacy and mathematics in PISA 2015. Dublin, Ireland: Educational Research Centre.

Smyth, E. (2016). Arts and cultural participation among children and young people: Insights from the Growing Up in Ireland study. Dublin, Ireland: Arts Council/ESRI.

Smyth, E. (2017). Off to a good start? Primary school experiences and the transition to second-level education. Dublin, Ireland: DCYA.

Smyth, E., Darmody, M., McGinnity, F., & Byrne, D. (2009). Adapting to diversity: Irish schools and newcomer students. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

Smyth, E., Lyons, M., & Darmody, M. (Eds.). (2012). Religious education in a multicultural Europe: Children, parents and schools. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Smyth, E., McCoy, S., & Kingston, G. (2015). Learning from the evaluation of DEIS. Dublin, Ireland: ESRI.

Taguma, M., Kim, M., Wurzburg, G., & Kelly, F. (2009). OECD reviews of migrant education: Ireland. Paris: OECD.

Watson, D., Lunn, P., Quinn, E., & Russell, H. (2011). Multiple disadvantage in Ireland: An analysis of Census 2006. Dublin, Ireland: Equality Authority and Economic and Social Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Darmody, M., Smyth, E. (2018). Immigrant Student Achievement and Educational Policy in Ireland. In: Volante, L., Klinger, D., Bilgili, O. (eds) Immigrant Student Achievement and Education Policy. Policy Implications of Research in Education, vol 9. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74063-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74063-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-74062-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-74063-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)