Abstract

This chapter explores the dynamic between end of program guidelines imposed on scholarship recipients (conditionality) and individual decisions and actions undertaken by these students (individual agency). Using the frameworks of human capital, education as a human right, and human capabilities, the chapter probes the logic of three categories of conditionality embedded in scholarship programs. Push and pull factors that influence post-graduation decisions are explored, as are the ways that conditionality can promote or limit interest in social change depending upon synergy or tensions between program goals and individual scholars’ plans. The chapter concludes by advocating for more flexible models of conditionality.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Learning Programs

- Scholarship Recipients

- Home Countrieshome Countries

- Scholarship Conditionality

- Learning Logic Models

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

A scholars hip alumnus from Moldova once told me how he had become enthralled with the idea of informational technology as a driver for development while studying in the United States. Upon his graduation, he was required to work for the Government of Moldova as a condition of his scholarship program. He had just begun the second year of a 3-year commitment when I asked him whether he could implement his new knowledge in his government position. He replied:

I tried to, but you know, my job now is not related to this.[…]I tried to look at opportunities for this social innovation hub; I was kind of thwarted because I have to work for government for three years, you know? That is something that is non-government. So, I have ideas, but I don’t know how to work on implementing them. So, I’m just watching how others do it.

This scholarship program alumnus speaks directly to a significant tension that can be present in international scholarship programs between the expectations and goals of scholarship funders and those of scholarship recipients in the years immediately following a student’s graduation. For some scholarship participants, the expectations of their funders and their personal choices align. Yet others—like the Moldovan alumnus quoted above—find themselves pulled between two opposing goals. In these situations, students may be disappointed, poised to challenge the conditions of the scholarship, or perhaps limited in their ability or interest to contribute to social change.

This chapter will explore these topics in greater detail, addressing the following questions:

-

1.

What do we know about the relationship between program guidelines set for students upon the completion of their scholarship (scholarship conditionality) and the decisions and actions made by a scholarship recipient (personal agency)?

-

2.

In what ways might scholarship conditionality promote or limit a person’s interest and involvement in social change?

To set the stage for answering these questions, it is worthwhile to revisit the three dominant frameworks found in scholarship program models. Each framework represents how various funders and administrators envision social change occurring through international higher education.

The first and most prominent framework is human capital theory , which states that through education a student develops knowledge and skills that become “fixed” in him or her (Smith 1952, p. 119) and will lead to greater economic gain. Taking this idea one step further, the effect of this education can “spill over” to positively influence others, leading to improved social and economic outcomes in the family , community, and workplace (McMahon 1999). In the case of scholarships, financial investment in one’s education will not only benefit that person, but it will “spill over” to positively influence the person’s workplace, community, and country.

A second common theory found in scholarship programs is that of education as a human rig ht (United Nations 1948), suggesting that the right to education is paramount and that scholarships are a way to level the opportunities available to talented students worldwide. One such example, as noted by Lehr (2008), is the case of Cuba , where the right to free education is written into the Cuban constitution. The government has extended their free tertiary education to professionals from other low- or middle-income countries with the expectation that these individuals will return home to use their knowledge for the development of their own countries (Richmond, cited in Lehr 2008).

The third approach is that of human capabilities (Sen 2003) t hat frames the goal of education as a vehicle to increase the individual’s choices and “freedom,” leading toward humans choosing a good life. As Melanie Walker argues, the human capabilities approach “implies a larger scope of benefits from education, which include enhancing the well-being and freedom of individuals and peoples, and influencing social change” (2012, p. 389). While many scholarship programs include reference to individual well-being and freedom as an important part of the scholar’s development, few have noted the goals of human capabilities among the program outputs.

With these three theories in mind, we next turn to a logic model that illustrates how many scholarship programs are designed.

2 A Logic Model Undergirding Scholarship Conditionality

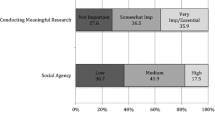

Most international scholarship programs are designed with the assumption that the scholarship—like higher education in general—prepares students for their future endeavors. The theory of change present in many programs is that a scholarship experience for individuals will eventually lead to a desired impact on social and economic development in their home country (Fig. 9.1) through graduates’ engagement in social change.

Composite logic model of internat ional scholarship programs that aim to spur social change (Campbell 2016a)

Those who design scholarship programs often think of the program in a normative or developmental way, assuming that participants will experience the program similarly and emerge better equipped to be agents of social change. These assumptions are to be expected as programs are typically designed before individuals are selected. However, a scholarship recipients’ effect on social change is not only hard to measure in practice, it can also be difficult to influence and, particularly, to predict. Models often fall short of capturing the breadth and range of experiences alumni can pursue following completion of the program.

To mitigate these uncertainties, many scholarship program administrators employ conditionality, setting certain expectations designed to influence participants’ choices, including the types of social change activities in which they engage. These conditions are typically placed on the period immediately following scholarship completion, typically for 1 to 3 years. It is this stage—the end of the academic scholarship when the grantee is planning for next steps—on which this chapter is focused.

3 Types of Scholarship Conditions and Program Provisions

Upon review of current and previous scholarship programs, three main types of post-scholarship conditions emerge: (1) bindin g agreements, (2) socia l contracts, and (3) vag ue post-scholarship guidelines. As will be explored below, these types of agreements often signal the underlying values and explicit goals of the scholarship program.

3.1 Binding Agreements

In binding agreements, individuals typ ically agree to the scholarship funds and the post-scholarship commitment at the outset. Usually, these post-scholarship bonds are a commitment to work following their studies, with the intention that the graduates will apply their newfound knowledge and skills for the gain of the sponsoring organization. Similarly, these binding agreements typically make clear the penalties if individuals do not fulfill their bond, such as having to pay back the costs of their education or jeopardizing the family home, which has been offered as collateral.

Binding agreements are often associated with international scholarships funded by private companies or national governments that typically send the student on a scholarship experience with the expectation they will return with new skills. Toward this aim, scholarships in this category likely specify the academic degree, the work conditions, and the length of service needed to fulfill the scholarship requirements. Examples include Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A* STAR), and the Gov ernme nt of Kazakhstan’s Bolashak Program, where surveyed alumni believe the requirement to work in Kazakhstan for five years is “appropriate, given the government’s investment in their educat ion” (Perna et al. 2015, p. 181). In addition, scholarships with binding agreements appear to be predominantly in applied fields—such as business, la w, government, science, or engineering—and within programs that support studying at the graduate level.

3.2 Social Contracts

The second typ e of scholarship condition is a social contract, or an approach where the funder delivers a strong, consistent message of what is expected of the grantee following their studies, without putting a binding agreement in place. Programs with social contracts are typically more open to individualized pathways for graduates, allowing the scholar to explore personal interests and exercise choice, while at the same time emphasizing a broad vision to which participants are expected to subscribe. To supplement this, funders may design specific program components aiming to prepare the student for their return (e.g., internships in the students’ home countries or project development or grant-writing courses ). Instead of penalizing non-compliant choices, programs in this category tend to incentivize the behaviors they wish to promote among their graduates through various mechanisms, including alumni grants, home country-based internships, job placement services, or by providing examples of outstanding alumni.

Programs with social contracts tend to have goals of nation- or multi-country-wide political, social, or economic development (nebulous terms with multiple pathways) and are likely to be funded by private foundations , host university programs, and high-income country government aid programs, whose goals are broad. They also tend to have a range of options for the student’s area of study. An example is the MasterCard Foundation Scholars Program, which aims to “create a movement of young leaders unified by a common purpose and a vision for economic and social change, particularly in Africa” through education, leadership development , career advising, and other forms of comprehensive support (2015, p. 2). For more information, see the MasterCard Foundation Scholars Program case study in this book.

3.3 Vague Post-scholarship Guidelines

The third catego ry is the vague post-scholarship guideline. Before or during these scholarship programs, there is little (or no) information provided to the individual recipients about the expectations of them following their scholarship education. Program materials may simply state that graduates are expected to return home, without clear indications of what types of activities or employment in which they are to engage. In some cases, the selection criteria for the program indicates that a successful candidate will demonstrate a commitment to their country of origin, which may be determined either through an essay sample or during a selection interview.

For programs with vague post-scholarship guidelines, there are likely multiple reasons that the conditions are unclear. First, the goal of the program may be to provide students with access to edu cati on—perhaps to a certain field or level of study not available in the students’ home country. Alternatively, the motivation may be aligned with diplomatic goodwill and cooperation. In many of these programs, students are “invited” to study in a foreign country. Such is the case of the Government of China scholarship programs for African students, which aims to build diplomatic goodwill (Dong and Chapman 2008) yet includes vague references for future economic cooperation (Nordtveit 2011).

Second, it may be that due to a difficult situation in the home country, students are not sure when it might be safe to return home or how they may apply their education, making it impossible to specify expectations. One such example is the Albert Einstein Academic Refugee Initiative sponsored by the UN’s Refugee Agency (UNHCR). UNHCR originally offered tertiary education scholarships across myriad fields, but after several years of implementation, chose to focus instead on business administration, social sciences, and medical sciences, as these degrees tended to give refugees greater chances of employment in their host countries (Morlang and Watson 2007). In a more recent example, the Institute for International Education’s (IIE) Syrian Consortium for Higher Education in Crisis which supports scholars and students to “continue their academic work in safe haven countries until they can return home” (IIE 2012).

Third, conditions may be vague for new programs, in cases where funders are not yet sure of the realistic expectations to place on their graduates. Yet with time and experience, programs language may be sharpened with more concrete terms. One illustrative case is th e US Government’s Muskie Program which used very basic program language about what the graduates could do in 2002, stating the successful candidates would be “committed to returning home after the completion of their program” (2002, p. 1). With time, this singular guideline on post-scholarship engagement has morphed to a more extensive set of expectations that included “sharing the benefit of the program with their community” and “becoming engaged in…endeavors designed to benefit the development of the home country” (American Embassy in Uzbekistan 2011).

3.4 Differential Impacts of Conditionality

It is worth asking whether these three different types of scholarship conditions inf luence participants in different ways. There is some evidence, for instance, that binding agreements positively influence participants to return to their home countries within 12 months of completing their studies (Marsh et al. 2016, p. 53). Those students with binding agreements might feel compelled to return based on the aims of the scholarship and to fulfill the commitments made, often combined with a sense of patriotism and will to give back for the privilege of studying abroad. Alternatively, they may be concerned about penalties applied if they do not return, although there is some evidentiary support that penalties do not strongly influence students’ choice, especially if they are recruited by local firms or emigrate to a third country (Basford and van Riemsdijk 2015).

A more general consideration is that different types of visa may be issued to the recipient based on the scholarship conditions, especially if the student is being “sent” to study abroad or is being “invited” by a host country or university. Visa stipulations are another way that expectations can be communicated to scholars, as they may dictate that participants return home immediately after their studies or can restrict future visits to the host country . However, visa regimes rarely force a person to remain in their home country; rather, they lengthen or curtail the permitted stay in the host country . As such, visas tend not to prevent recipients from subsequently relocating to another third country after returning home from a scholarship. For instance, a small minority of UK-funded Commonwealth Scholarship recipients are now resident in the United States (Mawer et al. 2016).

On the question of whether types of scholarship conditionality differently influ ence alumni engagement in social change and the types of activities chosen, little comparative research exists. This is partly because it is difficult to estimate graduates’ engagement in social change efforts soon after they return home. On the one hand, they may be energized by their study abroad and ready to enact change, while on the other hand, they are likely devoting time to managing their transition, finding employment, and dealing with cultural adjustment issues (see Gaw 2000).

4 Personal Agency and Factors Influencing Alumni Choice

Despite si milar scholarship program models, individuals experience their programs differently, make unique choices, and take advantage of distinct options at the end of their studies. In this section, three categories of forces that can affect a recipient’s scholarship experience are highlighted: individual agency, individual characteristics, and push and pull factors.

4.1 Individual Agency

Individual agency can be defined in relation to scholarship programs as the ownership for decisions and actions made by a scholarship grantee, given the options available at the time. It is how an individual exercises their choices and weighs their interests and desires against a given range of possibilities and specific life goals. Naturally, options change over time as the individual examines their abilities, grows and develops skills, reflects on their situation and future opportunities, and is exposed to, and creates, new social structures and relationships (Bandura 2001). Given this understanding, individual agency is a significant factor in how any individual will engage in social change efforts.

In the case of scholarship programs, a graduate’s viewpoint on available options is likely very different at the end of the scholarship than it was at the beginning. For example, students are exposed to advanced study with novel frameworks, enhanced skills and tools, em ployment opportunities, and new collaborators and networks . Students’ impressions of themselves, their estimation of their abilities, and their perception of past choices or situations may change. Moreover, the magnitude of the changes experienced by the students can vary widely among participants in a specific program, with some students changing their area of study, selecting a new career, or developing significant personal relationships. These potential shifts present new options and possible dilemmas for scholarship students.

As an example, I worked with an undergraduate scholarship recipient from southeastern Europe who became more comfortable sharing his sexual orientation—and began speaking out for others’ rights—during his studies in the United States. Until his time abroad, he had not talked about his homosexuality, beholden to, and shaped by, family and social constraints. With his newfound voice for sexual minority rights, he returned home to find an environment quite hostile to sexual minorities, with national policies proposed to criminalize certain behaviors and campaigns to ban gay marriage. At this time, the recipient felt stuck: he was unable, due to personal safety concerns, to follow the plan that he had crafted during his studies (supported by his scholarship funder) to publicly advocate for sexual minority rights. This vignette provides a good example of how agency, interests, and options may change during studies abroad and, moreover, how the ability to fight for social change may be in tension with the scholarship’s conditionality to return home.

4.2 Individual Characteristics

An intriguing question for those who study scholarship outcomes is whether specific factors may predict someone’s behavior following a program. While there are some interesting insights highlighted below, there is far from a holistic model to predict the pathway that individuals will follow. Moreover, I would suggest that searching for a predictive model of post-study outcomes is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, models ignore (or at least downplay) the participant’s agency—choices that are often vast for talented individuals like scholarsh ip alumni—and have no way to capture the myriad opportunities that exist for the scholar following their studies. Secondly, any sort of predictive model will likely be used as a tool to aid in the selection of scholars, prioritizing those with specific personal characteristics or those from certain countries. These types of predictive models are not only based on incomplete data but they are estimations that tend to be realized across large datasets: models are rarely well adapted to foreseeing individual results. The technique of using such models will invariably result in a blemished and biased selection process and should be avoided.

Factors that may affect an individual’s choice tend to fall into three categories: enduring factors, process characteristics, and external conditions and opportunities. These three categories of individual characteristics shed light on the complexity of both the factors influencing post-study decisions and, consequently, the practicality of expectations embedded in scholarship program conditionality.

4.2.1 Enduring Factors

Enduring factors are those characteristics that remain true throughout a lifetime, such as home country or childhood socioeconomic status. While these attributes may be weighed heavily in scholarship program selections, there is little evidence to show a strong correlation between enduring factors and post-scholarship behavior.

One of the more widely studied enduring factors is the relationship between different home countries and likelihood of the individual to return to that country post-scholarship. For example, in a review of approximately 2000 graduates of the United Kingdom’s contrib ution to the Commonwealth Scholarship and Fellowship Plan, researchers found that recipients from certain global regions, like Australasia, had a statistically significant lower rate of return, while other regions, like Southeast Asia, had a higher rate (Mawer et al. 2016). Moreover, certain coun tries—with Nigeria specifically mentioned—had a disproportionate number of alumni abroad.Footnote 1 Interestingly, this study also found that scholarship recipients’ likelihood of living in their home countr y changed depending on the number of years since they completed their scholarship, with those students who completed their scholarship in the last 1–2 years most likely to be living in their home country (Mawer et al. 2016). While these findings help illuminate the complex picture of student return after scholarship, they could not be separated into meaningful patterns of which nationalities were most or least likely to return immediately after their scholarships.

In another example, a recent report on African alumniFootnote 2 who attended five universities in North and Central America found statistically significant regional variance in return rate (Marsh et al. 2016). Students from West Africa were found to return home at a lower rate than those from East and Southern Africa. In addition, the authors noted that Africans who had studied abroad were more likely to return to their home country if they were married or in a long-term relationship prior to studying abroad. African students surveyed for the report were also more likely to return to their home country if their parents had lower levels of education, but there was a weak or non-existent relationship between the likelihood of a student returning to their home country based on their gender, childhood economic status, or type of home community (rural or urban).

4.2.2 Process Characteristics

Process characteristics are those factors that are related to the scholarship, such as university attended or degree earned. For some process characteristics, the outcome may be significantly different between the time when one was selected for a scholarship and when they graduate, such as the knowledge or experience gained during the participant’s studies.

Of these factors, there is some evidence to suggest that the level of degree earned is significant in whether the individual will return home. Chang and Milan (2012) found that many (73.3%) foreign PhD students in US scie nce, engineering, or health fields stated that their immediate post-gradu ation plan was to remain in the United States. Moreover, there is some evidence that the chances of a PhD graduate choosing to return home has decreased with time. Kim et al. (2011) found that the percentages of US PhDs (across disciplines) who stayed in the United States increased from 33.9% during the 1980s to 66.1% during the 2000s. Marsh et al. (2016) found that African graduates had a higher rate of return in the 1960s–1980s, with a decline thereafter. They also found that African PhD holders were more likely to return than those who had pursued an undergraduate degree abroad, likely due to greater professional networks and personal responsibilities later in life (Marsh et al. 2016). Notably, these studies do not focus specifically on scholarship grantees and the doctoral statistics are likely skewed by the sciences and engineering fields, where research and development postdoctoral appointments are common next steps in career trajectories (Finn 2014).

Students may gain a host of additional skills while studying abroad, including language proficiency, intercultural skills, self-confidence, openness to learning, and flexibility (Dwyer and Peters 2004; Williams 2005). Baláž and Williams (2004) note that students can also build personal and professional networks while studying overseas. Furthermore, international study has been shown to influence individuals’ career trajectories, like spurring an interest in overseas employment opportunities or working in an international organization (Norris and Gillespie 2009). These factors—some of which have been discussed in more detail in Chap. 6—can also shape an individual’s post-scholarship steps.

Two additional components that are often included in international scholarships programs that may influence participants’ post-scholarship choices are community service learning experiences and professional internships . In their study of African alumni, Marsh et al. (2016) reported that 39% of alumni who participated in service learning or volunteering activities, and 29% who had internships , said that they used these experiences often or very often in their current work. The authors also found a significant correlation between scholarship recipients who worked in the host country during their studies and lower rates of return to the home country (Marsh et al. 2016). Moreover, anecdotal evidence indicates that the professional connections made through these volunteer and professional opportunities are likely to influence grantees’ post-scholarship choices, as some of the temporary engagements become permanent. In sum, the knowledge and experience gained during the scholarship will inevitably influence the post-scholarship pathway.

4.2.3 External Conditions and Opportunities

The third category, external conditions and opportunities, is a collection of environmental factors that exist outside of the scholar and scholarship program. These are the contextual factors that can influence the individual’s choices, such as professional opportunities or the economic conditions in the students’ home country. Unlike enduring factors, external conditions and opportunities are dynamic and can vary dramatically given the state of a specific professional field or current events.

Academic literature points to a few specific conditions in the home country that may influence scholarship recipients’ decision to return to, work in, and stay in their home countries . The first set of these factors relates to employment opportunities and the culture of the workplace. Tung and Lazarova (2006) found that in a study of Romanian scholarship alumni , 58% would like to leave Romania and work abroad if given the opportunity. Interestingly, one of the chief reasons for seeking employment abroad was due to the work culture, with 54% of the respondents identifying that the professional standards they experienced while studying abroad “were in conflict” with the work culture at home (2006, p. 1863).

The daily tension of working in a professional environment that does not fit expectations likely takes a toll on the scholarship alumnus, both through struggling under the system that clashes with their professional experiences abroad and the energy required to attempt to advocate for a shift in standards. Among scholarship alumni I have interviewed, expectations to comply with unscrupulous practices in government, higher education, the judiciary, and law enforcement caused some of them to seek positions elsewhere (Campbell 2016a). On this point, Tung and Lazarova suggested that the students’ scholarships “allowed them to attain further experience in Western universities, thus making them even more valuable to their home countries – and ironically – less likely to return there” (2006, p. 1857). These points raise questions about whether it is reasonable to expect skilled professionals to return to work in positions in which the organizational culture is notably different than the overseas professional environments to which they adapted.

Often scholarship recipients from lower-income countries are concerned about the q uality of materials or resources available in their home countries to continue their work. In the case of Kenya , for instance, Odhiambo (2013) noted that due to low-quality facilities and few professional development opportunities—in addition to a significant increase in student enrollment and low professor salaries —many faculty leave Kenyan universities. Exodus from research and teaching posts appears to be especially acute in the Science, Technology, Engineering , and Mathematics (STEM) fields, where high-quality labs are expensive to establish and maintain. Some governments have been aware of this problem and able to invest in mitigation through incentives and better infrastructure investment. Both Pan (2011) and Zha and Wang (Chap. 12) have observed that the Chinese government devoted considerable funding to developing “returning-student entrepreneurial parks”—complete with start-up loans and tax breaks—to entice those Chinese academics abroad to return and engage in work to spur national development.

In addition to employment factors, other external conditions and opportunities—such as the social, political, and economic contexts of the home country—may shape scholars’ decisions. In a comparative study of the ways that scholarship alumni perceive their contribution to social change in the Republics of Georgia and Moldova, I found that alumni were more interested in returning home and working for social change when the current government was actively involved in promoting democratic ideals, improving services, and eradicating corruption (Campbell 2016a). In this transition from a Soviet system to a new democracy , alumni took up positions that they believed were directly related to social change, often in government and non-governmental organizations. Moreover, in the case of Georgia , a strong alumni network helped the alumni to support each other in job searches, volunteer work, establishing new community projects , and for support (Campbell 2016b).

4.3 Overall Push and Pull Factors

Wh en the idea of personal agency is combined with the characteristics of the individual, features of the scholarship program, environmental conditions, and opportunities available to the scholar, the result is what international student mobility scholars often refer to as push and pull factors. Push factors are the elements that drive an individual to move away from their current location, whereas pull factors are those elements that attract them to the new location. Together, these factors help to illustrate how individuals often weigh a multitude of diverse elements when making career and life choices. For international scholarship recipients, there tend to be additional factors—beyond those weighed by their peers or others who may be contemplating mobility for economic or other reasons—including scholarship conditionality.

Much discussion of push and pull factors has been conducted on a macro level and in the context of the global competition for talent: Marsh and Uwaifo examine this literature in Chap. 11. Two studies that have taken a richer, more detailed look specifically at push and pull factors related to post-scholarship choices have been published b y Baxter (2014) and Polovina (2011). In the first stud y, Baxter (2014) interviewed 34 participants in the Rwandan Presidential Scholarship Program. The interviewees outlined factors that influenced their choices of whether to return home following their scholarship studies in the United States. Among these, economic considerations, workplace conditions, and political stability in their home country , and sense of identity and belonging, were all noted as important. The study also highlighted one important aspect that goes typically unaccounted for in push and pull models: expectations set by the students’ family . For some scholarship recipients, especially those from poor communities or families , family members encouraged them to seize their opportunities abroad to find a job with a higher salary and send additional funds home. Moreover, participants in the study reported that they felt “ill-equipped” with only undergraduate studies to enter Rw anda’s workforce, with many reporting they hoped to pursue further education before returning home.

In the second study, which looked at 27 Serbian scholarship alumni , Polovina (2011) reported push and pull factors for both those living abroad (the “mobile” group) and those alumni who were currently living in Serbia (the “immobile” group). Both groups were initially driven to study abroad because they believed the experience would build confidence; both groups were motivated to return to their home country because of their family and friend networks ; and both also suggested that their desire to leave Serbia is partially because of a disorganized or “ruined” state system that did not appear to be changing (Polovina 2011). Interestingly, the most significant differences of opinion between the groups were in the perceived quality of higher education, support for research, opportunities to work with experts and observe new practices, and the potential of career development within the sciences: the mobile group all stated that there were greater opportunities abroad.

Push and pull factors are also likely to change over the individual’s life. Return decisions are not necessarily permanent and may be delayed, especially as careers and personal considerations change. For example, the alumni may receive a career promotion that “pulls” them to a large global city or back home. Alternatively, graduates may be “pulled” to another location when they have children and choose a new location with a better school system. On the other hand, if the economy in their country of residence spirals down or a civil war breaks out, alumni are “pushed” to reconsider their current residence. In my own research (e.g., Campbell 2016a), I have observed that a grantee’s relationship to their home country—and the advocacy work in which they are involved—can shift during their lives. For example, a scholarship alumnus living abroad may return home if a national revolution ushers in a new government whose leaders welcome progressive ideas from abroad. This phenomenon has been seen recently in Ukraine , where Ukrainian alumni from western universities have responded to over 50 requests for advice from the post-Maidan government, and some have been placed in leadership positions (Professional Government Initiative 2016).

As the range of push and pull factors indicates, scholarship conditionality is only one consideration among many. Graduation is a natural point at which the scholarship recipient will carefully consider next steps, but it is at this point—immediately upon the completion of studies—that conditionality requirements (and visa regulations ) are almost always applied. Recipients can therefore find themselves in a position of little time and many options, leading to increased anxiety. Yet with such a broad range of considerations in play, scholars who choose not to follow the conditions of their scholarship program may not be intentionally defying their goals. In fact, they may be pursuing options that they believe position them better for future contributions to social change, such as further education, internships in a certain organization, or seeking partners or funders for nascent projects. As some of the examples above indicate, while program conditionality may be a factor immediately upon graduation, wider commitment to both returning home and contributing to social change will likely vary across a much broader time span.

5 Points of Tension in Scholarship Programs

As types of scholarship conditionality, one’s personal agency, and individual predictive factors coalesce into push and pull factors, tensions can manifest in many international scholarship programs . Unresolved, these tensions may lead participants to be unprepared for their post-scholarship activities, frustrated with their position, and set awry on the mission to support and spur social change following their studies. At the outset of this chapter, I outlined three theories that undergird scholarship program design : human capital theory , a human rights-based approach, and a human capabiliti es framework. Each framework not only implies a different goal or measurement of success, it also influences how the program is designed in the first place, including the type of conditionality attached to the scholarship.

The theories align well with the three broad approaches to scholarship conditionality. Programs that subscribe to human capital theory —that the student’s education will lead to both increased income and a “spillover effect” to boost economic and social conditions in their hom e communities—are likely to issue binding contracts. These contracts require individuals to return home for specific employment assignments so that home countries reap a return on the educational investment. Programs rooted in a rights-based approach focus on access to education for the participant and the role the participant has in promoting others’ rights following their studies. Conditionality tends to follow one of two routes: vague guidelines are more likely associated with programs whose goal is to provide access to ed ucation, whereas social contracts are likely for programs that aim to steer their participants to promote rights for others. Finally, programs that prioritize a human capabilities approach encourage participants to explore new fields and topics, are flexible to a student’s changing interests, and emphasize personal choice in their post-scholarship activities. These programs are more likely to have vague or flexible post-scholarship guidelines, with the message that the next step for the scholar is to maximize their potential impact, regardless of vocation or residency.

The tension lies in that some programs combine theories or send mixed messages to their students. For example, it would be illogical to require a graduate who has been part of a program steeped in human capabilities —with an emphasis on developing new interests—to return to a low-paying, entry-level job in government when their interests and skills no longer match this position. This is the case of the Moldovan scholarship alumnus quoted on the first page of this chapter, who developed a new interest in technology for development but was unable to move this idea forward given the conditions of his scholarship contract.

Unfortunately, the tension of having unclear or multiple theories of change within a single scholarship program can ultimately lead to lack of clarity of successful outcomes resulting in frustration, for both administrators and participants. Without clarity of theory and values, scholarship program administrators pass the burden of trying to achieve multiple goals to their participants. Mixing of theories—and subsequently the shaping of program values and activities—places significant pressure on an individual to accomplish all things, potentially diluting any single objective.

More generally, scholarship programs are designed in a logical, normative fashion, with the assumption that selected scholars will have a parallel experience in a sequential way, leading to similar or complementary outcomes that contribute to change in the students’ home countries . While some funders understand that each host university will provide a different experience for their grantees, many programs are designed with the following assumptions: that participants are similar and will experience the program in a symmetrical way, that participants will be shaped during their studies, and that overseas higher education will prepare them for their home countries (see Chap. 6 for further discussion). Scholarship conditionality is added to programs to make explicit the expectations for scholarship grantees to contribute to social or economic change in their home countries . Moreover, students within a program are often given the same “ty pes” of education (level, quality of institution, length of program) with similar supplemental training leading to the same expectations: that students will participate in social change following their graduation and beyond.

This single program design model—found most commonly among programs in line with human capital theory —does not always allow for personal agency and individual characteristics and contributions. Few models incorporate grantees’ motivations for applying, the skills and experience they bring to the program, their enduring attributes and new opportunities and skills presented during the scholarship, their plans for their future, and how they may go on to influence social change. For example, what if a student enrolled in a Master’s of Public Administration degree with a commitment to return and work for their Ministry of Economy finds they have a passion for public health? Would a degree in public health also positively contribute to social change development in the home country? The answer is surely yes, yet some programs would not permit a degree change due to strict program guidelines and conditionality agreements.

It may not be only a change of interests: it could also be a shift of identity. For example, Rizvi (2005) suggests that while studying abroad, students can become “dislodged” from their home countries and their devotion to helping the country, resulting in a “transnational” identity where they associate with a blend of home and host cultures. Indeed, some programs actively promote a similar idea of the “global citizen .” Likewise, students may expand their interest in social change to a range of issues that extend beyond the borders of their country. For example, a student with experience fighting for fair wages in rural Nicaragua may expand her familiarity and interest in working with advocates who campaign for global pay equity for women across Latin America . Therefore, scholarship models that are focused on applying an individual’s skills and efforts to national development may not be flexible enough to accommodate, account for—and welcome—the inevitable change experienced by participants who subsequently expanded their horizons.

6 Conclusion and Implications

As is evident from my framing of the issues above, I believe scholarship conditionality and individual agency may collide, exposing tensions in competing theories of change, incongruences in program models, and unclear and multiple expectations placed on participants. In truth, there is still a gap in the understanding of how conditionality may affect individuals and their roles in social change, both in the first few years after a scholarship and in the longer term. Longitudinal research across cohorts of a scholarship program or different programs across countries could illuminate what types of support were most useful to the recipients in their quest to create social change.

To help overcome these difficulties with conditionality and agency, we need new models for scholarship programs that allow for recipients to develop their interests, expand their networks , and increase their choices during the scholarship period, with significant support given to the alumni’s social change engagement in the long term. Instead of trying to fit talented individuals into predetermined job descriptions or setting predetermined outcomes of how knowledge and skills will be applied upon graduation, funders should consider allowing the individual the freedom to build on their experiences, choose their pathways, and design projects or positions that contribute to the home country. These new models could be in the form of individualized scholarship plans in which recipients set personal goals, allowing for change and growth within that plan while they continue to expand their knowledge and skills and seek new opportunities to help their country. In addition, flexible plans will also fit the changing contours of students’ home countries. These plans could be monitored by an advisor who could incorporate students’ personal push and pull factors, home coun try connections and networks , and resources available at the students’ host universities; all contributing to a specialized engagement plan for social change.

This reframing would change and expand the notion of scholarship conditionality. Instead of top-down, one-size-fits-all approach, conditionality agreements can be reconceived as planning tools for the important and dynamic social change work following academic study. With more personalized, flexible notions of conditionality, scholarship program alumni can continue to be supported from the moment of graduation far into their career and social change trajectories.

Notes

- 1.

Notably, most alumni who lived abroad did so in countries with higher Human Development Indicator (HDI) scores than their country of origin.

- 2.

Not all participants in this study were part of an international scholarship program.

References

American Embassy in Uzbekistan. (2011). Edmund S. Muskie Graduate Fellowship Program paper application instructions. American Embassy in Uzbekistan. Available at: http://photos.state.gov/libraries/uzbekistan/231771/PDFs/2012%20Muskie%20Paper%20Application%20Instructions%20_Uzbekistan_.pdf (Accessed 31 October 2016).

Baláž, V. and Williams, A.M. (2004), ‘Been there, done that’: international student migration and human capital transfers from the UK to Slovakia. Population, Space and Place, 10(3), pp. 217–237.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), pp. 1–26.

Basford, S. and van Riemsdijk, M. (2015). The Role of Institutions in the Student Migrant Experience: Norway's Quota Scheme. Population, Space and Place. Early view: doi: 10.1002/psp.2005.

Baxter, A. (2014). The burden of privilege: Navigating transnational space and migration dilemmas among Rwandan scholarship students in the U.S. PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, University of Minnesota. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11299/166947 (Accessed 6 Dec 2016).

Campbell, A. (2016a). International scholarship programs and home country economic and social development: Comparing Georgian and Moldovan alumni experiences of “giving back”. PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota.

Campbell, A. (2016b). International scholarship graduates influencing social and economic development at home: The role of alumni networks in Georgia and Moldova. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 19(1), pp. 76–91.

Chang, W.Y. and Milan, L.M. (2012). International Mobility and Employment Characteristics among Recent Recipients of US Doctorates. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Available at: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/infbrief/nsf13300/ (Accessed 11 June 2016).

Dong, L. and Chapman, D.W. (2008). The Chinese Government Scholarship Program: an effective form of foreign assistance? International Review of Education, 54(2), pp. 155–173.

Dwyer, M., and Peters, C. (2004). The benefits of study abroad. Transitions Abroad, 27(5), pp. 56–57.

Edmund S. Muskie/Freedom Support Act Graduate Fellowship Program. (2002). 2002 Program Description. Unpublished document.

Finn, M. G. (2014). Stay rates of foreign doctorate recipients from U.S. universities, 2011. Report Prepared the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics of the National Science Foundation. Available at: https://orise.orau.gov/files/sep/stay-rates-foreign-doctorate-recipients-2011.pdf (Accessed 8 November 2016).

Gaw, K.F. (2000). Reverse culture shock in students returning from overseas. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24(1), pp. 83–104.

Institute of International Education. (2012). IIE consortium commits to emergency support for Syrian students and scholars: 33 organizations worldwide commit over $1.3 Million. Press Release. Available at: http://www.iie.org/Who-We-Are/News-and-Events/Press-Center/Press-Releases/2012/2012-11-14-IIE-Consortium-Commits-to-Emergency-Support-for-Syrian-Students-Scholars#.V2KowLQ0f8k (Accessed 13 April 2016).

Kim, D., Bankart, C.A. and Isdell, L. (2011). International doctorates: Trends analysis on their decision to stay in US. Higher Education, 62(2), pp. 141–161.

Lehr, S. (2008). Ethical dilemmas in individual and collective rights-based approaches to tertiary education scholarships: the cases of Canada and Cuba. Comparative Education, 44(4), pp. 425–444.

Marsh, R., Baxter, A., Di Genova, L., Jamison, A., and Madden, M. (2016). Career choices, return pathways and social contributions: The African alumni project. Full report prepared for the MasterCard Foundation Scholars Program. The MasterCard Foundation, Toronto, Canada. Available at: http://africanalumni.berkeley.edu/media/African-Alumni-Project-Final-Full-Report-Aug-2016.pdf (Accessed 8 November 2016).

Mawer, M., Quraishi, S. and Day, R. (2016). Successes and complexities: The outcomes of the UK Commonwealth Scholarships 1960–2012. Full Report. Available at: http://cscuk.dfid.gov.uk/2016/04/successes-and-complexities-the-outcomes-of-uk-commonwealth-scholarships-1960-2012/ (Accessed 6 Dec 2016).

McMahon, W.W. (1999). Education and development: Measuring the social benefits. Oxford University Press.

Morlang, C. and Watson, S. (2007). Tertiary refugee education impact and achievements: 15 Years of DAFI. UNHCR Report. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/uk/568bc70e9.html (Accessed 11 June 2016).

Nordtveit, B.H. (2011). An emerging donor in education and development: A case study of China in Cameroon. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(2), pp. 99–108.

Norris, E.M. and Gillespie, J. (2009). How study abroad shapes global careers evidence from the United States. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(3), pp. 382–397.

Odhiambo, G.O. (2013). Academic brain drain: Impact and implications for public higher education quality in Kenya. Research in Comparative and International Education, 8(4), pp. 510–523.

Pan, S.Y. (2011). Education abroad, human capital development, and national competitiveness: China’s brain gain strategies. Frontiers of Education in China, 6(1), pp. 106–138.

Perna, L.W., Orosz, K., Jumakulov, Z., Kishkentayeva, M. and Ashirbekov, A. (2015). Understanding the programmatic and contextual forces that influence participation in a government-sponsored international student-mobility program. Higher Education, 69(2), pp. 173–188.

Polovina, N. (2011). Are scholarships and mobility programs sources of brain gain or brain drain: The case of Serbia. In: N. Polovina and T. Pavlov (eds), Mobility and emigration of professionals: Personal and social gains and losses, pp. 164–181. Belgrade, Serbia: Group 484 and Institute for Educational Research.

Professional Government Initiative. (2016). Professional Government Initiative: By Ukrainian Alumni of world-class universities. Available at: http://www.proukrgov.org/eng (Accessed 12 October 2016).

Rizvi, F. (2005). Rethinking “brain drain” in the era of globalisation. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 25(2), pp. 175–192.

Sen, A. (2003). Human capital and human capabilities. In: Fukuda-Parr, S. and Shiva Kumar, A.K. (eds). Readings in Human Development: Concepts, measures and policies for a development paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. (1952). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations: In: R. M. Hutchins and M.J. Adlers (eds), Great books of the western world: Vol. 39. Adam Smith. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica (Original Work published 1776).

The MasterCard Foundation Scholars Program. (2015). Developing young leaders: 2015 Handbook. Toronto: The MasterCard Foundation.

Tung, R.L. and Lazarova, M. (2006). Brain drain versus brain gain: an exploratory study of ex-host country nationals in Central and East Europe. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(11), pp. 1853–1872.

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (Accessed 8 November 2016).

Walker, M. (2012). A capital or capabilities education narrative in a world of staggering inequalities? International Journal of Educational Development, 32(3), pp. 384–393.

Williams, T.R. (2005). Exploring the impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural communication skills: Adaptability and sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(4), pp. 356–371.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Campbell, A.C. (2018). Influencing Pathways to Social Change: Scholarship Program Conditionality and Individual Agency. In: Dassin, J., Marsh, R., Mawer, M. (eds) International Scholarships in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62734-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62734-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-62733-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-62734-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)