Abstract

Research in the sharing economy predominately focuses on issues related to the exchange parties and the sharing platforms, ignoring the secondary market of the numerous entrepreneurs emerging around sharing ecosystems. By conducting an exploratory study, this chapter first identified the secondary market entrepreneurs supporting the Airbnb ecosystem and then, it investigated how they impact the sharing accommodation experiences by categorising their services based on the Porter's value chain model. The study also investigated the ability of these entrepreneurs to shape and form new ‘hospitality’ markets by categorising their market forming capabilities according to the “learning with the market” framework. Findings reveal that the services provided by these entrepreneurs: are similar to the accommodation services provided in the commercialised hospitality context; and they influence the market practices of the ‘trading’ actors participating in the Airbnb ecosystem. Consequently, the sub-economies created by the secondary market of these entrepreneurs are shaping and evolving the sharing accommodation market to a commercialised ‘authentic’ hospitality experience.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

9.1 Introduction

The sharing economy is rapidly being diffused in all industries and the accommodation sector is not an exception (Sigala 2014). Consequently, increasing attention is being paid to the peer-to-peer economy in tourism research (Tussyadiah and Pesonen 2015). However, research has solely focused on studying issues related solely to the exchange parties (i.e. accommodation hosts and guests) and the sharing platforms, ignoring a growing number of entrepreneurs that are emerging around sharing ecosystems in order to facilitate the trading actors to easier exchange resources in the sharing economy (e.g. Fradkin 2013; Fradkin et al. 2014). On the other hand, preliminary findings show that the sharing economy is fuelling a plethora of new entrepreneurs, and this entrepreneurialism expands the scope and the scale of several economic systems and economies (Botsman 2014; Koopman et al. 2014; Burtch et al. 2016). Claims also exist that the increasing gap between productivity and employment metrics in the USA (showing a decoupling of economic activity and employment) may be due to the entrepreneurial activity fueled by the sharing economy that is invisible in official labour statistics (Badger 2013). These sharing economy entrepreneurs do something so un-traditional that is yet not defined and measured. They follow un-traditional work patterns and they are driven by unconventional and controversial entrepreneurial motives (i.e. drivers combining at the same time commercial entrepreneurial drivers with genuine and altruistic motives to provide social value). Thus, it is also advocated that the services of these micro-entrepreneurs redefine the nature of the initially authentic sharing economy offerings. However, although the sharing economy is challenging the fundamental institutions of employment, work and entrepreneurship (Sundararajan 2016), the literature has failed to far to provide an understanding of this new type and nature of entrepreneurship as well as of the latter’s impact on the value and offerings of the sharing economy.

In this vein, the aims of this study are twofold: (1) identify the type of the entrepreneurs that are emerging around the Airbnb sharing ecosystem; and (2) analyse the services provided by these entrepreneurs in order to better understand how their activity affects the hospitality market and experience that are being formed and provided through the Airbnb sharing ecosystem. Airbnb was selected as a case study for this research, because by being one of the biggest sharing accommodation platforms, its industry impact is substantial (Mahajan 2015). Airbnb currently receives more online bookings than any hotel chain, and it is projected to process almost 100 million bookings beyond 2016, with a 40%–50% growth in accommodation offered per year (Huston 2015). Recently, Airbnb also introduced a new B2B functionality allowing companies to book Airbnb listings for their employees. Entrepreneurs operating around the Airbnb sharing ecosystem were found by conducting a major internet search. The websites of these entrepreneurs were analysed for investigating their business models and services. Findings reveal that they basically support Airbnb hosts by outsourcing them (accommodation) management services that are primarily found in the traditional hospitality industry. Consequently, by adapting and transferring traditional accommodation services from the commercialised to the shared accommodation, the sub-economies of these entrepreneurs contribute to the commercialisation of the ‘authentic’ hospitality experience that Airbnb claims to provide.

9.2 Sharing Economy in the Accomodation Sector: Research Background and Evolution

The sharing economy is widely viewed as a network of connected individuals, communities, and/or organizations that utilizes an online platform to facilitate exchanges, interactions, and experiences for enabling a diversity of exchanges (i.e. lending, renting, swapping, gifting, bartering, sharing, etc.) (Botsman and Rogers 2011). However, although this definition highlights the development of the sharing economy around an ecosystem of various actors interacting and exchanging resources for co-creating value, current research has failed to examine the totality of the actors operating in the sharing economy and specifically, the new entrepreneurs that are emerging around sharing ecosystems and they are contributing with their practices to the restructuring, redefinition and reformation of the traditional economic value systems and chains. Indeed, past research on the sharing economy focuses primarily on the exchanging actors and the sharing platforms (e.g. Fradkin 2013; Fradkin et al. 2014) as well as the socio-economic impacts of the exchanges on communities and employment (Greenwood and Agarwal 2015; Zervas et al. 2015).

Similarly, previous research about the sharing economy in the accommodation sector has examined: the adoption, motivation and values/benefits that hosts and guests derive from trading hospitality services (e.g. Stern 2014; Ikkala and Lampinen 2014); the business model, branding, the technological systems and functionality of the sharing platform like Airbnb (e.g. Fradkin et al. 2014; Yannopoulou et al. 2013); and/or the macro-economic impacts of collaborative exchanges on various socio-economic and cultural issues such as privacy, taxation, legislation, tourism employment, hotel industry, communities and social discrimination (Zervas et al. 2015; Neeser et al. 2015; Miller 2014; Zekanovic-Korona and Grzunov 2014; Guttentag 2013; Fang et al. 2015). Research has also focused on the experiences that people strive to get or they are getting in the shared accommodation. Specifically, findings show that the major experiences and benefits sought by Airbnb guests include: authentic hospitality experiences; social interactions; the experience of domesticity, community, sustainability; but also home and hotel amenities (e.g. laundry facilities, wifi) and low prices (Tussyadiah 2015; Guttentag 2013; Tussyadiah and Pesonen 2016; Lane and Woodworth 2016). These studies mainly highlight that the shared accommodation market is different from the traditional accommodation market, as: it seeks different hospitality experiences; and it represents new tourism market, as the latter would not have travelled unless if the “cheap/affordable” shared accommodation option was available.

On the other hand, another stream of studies also shows that an increasing number of Airbnb guests perceive, select and evaluate the shared hospitality experience in a similar way as the one they use for selecting and evaluating a commercialized hospitality product. For example, Guttentag (2013) found that many Airbnb guests’ select shared accommodation options by using criteria that are comparable to the ones used by tourists when selecting traditional accommodation (e.g. service quality, reputation, comfort and equipment, location, price and security). Other studies (Möhlmann 2015; Ert et al. 2016; Olson 2013) have also found that in both the Airbnb and the traditional hospitality context, the guest satisfaction and the likelihood to re-book are determined by the following similar factors: functionality, quality and utility of the accommodation services; trust to the host; economic value and considerations. Moreover, instead of interacting, getting to know each other and exchanging authentic experiences and lifestyles, many studies have also shown that the financial benefit (i.e. extra income or money savings) is the predominant motivation for both sides (guests and hosts) to participate in the sharing economy (Guttentag, 2013; Möhlmann 2015; Tussyadiah 2015). Finally, some studies also challenge the previous arguments that the shared accommodation expands rather than substitutes the traditional hospitality market. For example, Guttentag (2013) and Zervas et al. (2015) found that the lower-priced hotels are negatively affected by the growth of the Airbnb bookings, which in turn confirms the disruption caused by the Airbnb to the traditional accommodation sector.

Moreover, the literature about the sharing economy has also evolved towards a new stream of research examining how shared accommodation providers can participate and effectively use sharing platforms for maximizing their ‘sales’ and economic benefits. For example: Ert et al. (2016) investigated the factors (e.g. competitors’ prices, hosts’ reviews and trust) affecting the prices of shared accommodation promoted in Airbnb; Hill (2015) analysed how Airbnb hosts can use the pricing tip tool offered by Airbnb for setting competitive prices. Overall, an increasing number of studies stresses that if Airbnb hosts wish to succeed and to be selected by Airbnb users, then the former have to adopt an operational mindset and management practices (e.g. trust building, managing customer reviews, addressing competitors’ prices or applying emotional pricing) that are similar to the business decision-making processes and practices adopted by commercial hotels.

Thus overall, research in the shared accommodation shows that demand-pull factors (i.e. guests’ preferences, decision-making criteria and behaviour) and supply-push factors (i.e. maximisation of economic benefits, competitiveness, entrepreneurial goals) exercise pressures to the shared accommodation providers to adopt traditional hospitality management practices and mindset. These simultaneous demand-pull and supply-push pressures demand the Airbnb hosts to act as sharing economy entrepreneurs, social media marketers and hospitality providers. However, shared accommodation providers typically lack general business or specific hospitality knowledge, which in turn undermines their ‘business performance’ in the sharing economy. This has spurred second-order entrepreneurialism within the sharing economy. Particularly numerous entrepreneurs have set-up new companies that outsource management services (e.g. pricing, booking services and management capabilities) to Airbnb accommodation providers to enable them to operate and trade their hospitality services more efficiently and effectively. However, although professional publications increasingly highlight the mushrooming emergence of entrepreneurs around sharing ecosystems, none academic study has examined so far how these start-up companies support but also transform the value chain, the hospitality experience and the market of the shared accommodation sector.

9.3 Entrepreneurship in the Sharing Economy and Its Role on the Economy and Market Formation

The current socio-economic and technological environment is widely recognised to inspire and fuel entrepreneurial activity. Indeed, knowledge assets and technological advances are considered as the strategic assets and enablers of the modern entrepreneurs (Audretsch and Thurik 2001; Thurik 2008), who also differ from traditional entrepreneurs because of their knowledge-intensive and technology-driven process and attitude (Romano et al. 2016). Modern entrepreneurs need to manage three levels of knowledge (domain, organisational and technological knowledge, Malerba 2010) and they are subject to both business risks (market potential) and technology risks (reliability and continuous innovativeness of technology) (Byers et al. 2011). The sharing economy is identified as a major type of entrepreneurship 3.0, a concept developed by Maeyer and Bonne (2015) to refer to the entrepreneurial activity generated and fuelled by the technological advances and the crowdfunding opportunities. Being knowledge-intensive and technology-driven, the success the sharing economy entrepreneurship depends on three major factors (Standing and Mattsson 2016): market opportunity recognition, business model development and technology commercialisation.

The press (Badger 2013; Zumbrun and Sussman 2015) and academia (Sundararajan 2014; Botsman 2014; Koopman et al. 2014; Burtch et al. 2016) have already started looking into the influence of the sharing or gig-economy to boost entrepreneurial activity through flexible employment and micro-entrepreneurship. However, the literature and preliminary findings do not provide conclusive results into the impact of the sharing economy on entrepreneurship, because (Burtch et al. 2016): people providing their labour in sharing economy platforms do not perceive themselves as entrepreneurs, and so a better understanding and definition of the type of entrepreneurship or employment that the sharing economy creates is required; and the theory provides competing but equally compelling arguments that the sharing economy can either increase or decrease entrepreneurial activity.

On the one hand, it is widely argued that entrepreneurship depends on the availability of slack resources (Aggarwal et al. 2012). For example, Uber and Airbnb enables would-be entrepreneurs to set up their own schedules and working patterns while earning stable pay (Hall and Krueger 2015; Swarns 2014); in turn, by exploiting this flexibility for their own benefit, people can then devote resources to ventures without loosing financial security. On the other hand, the literature also argues that un- and under-employment can drive entrepreneurial activity, because people with unacceptable employment options and/or low opportunity costs are motivated to become entrepreneurs as they have excess time and/or can hope for higher economic benefits (Acs and Armington 2006; Fairlie 2002; Storey 1991). Consequently, for people that pursue entrepreneurship as a means of resolving un-employment or under-employment (Fairlie 2002; Storey 1991), the sharing economy will decrease their entrepreneurial activity by providing them alternate employment opportunities. Only one recent study (Burtch et al. 2016) tested these competing theoretical arguments and its findings confirm a dual impact of the sharing economy on entrepreneurship, as initial evidence reveals that the sharing economy jobs may, on average, substitute for lower quality entrepreneurial activity rather than act as a complement to higher quality entrepreneurial activity. In other words, the sharing economy has a different influence on different types of entrepreneurial activity (low vs. high quality).

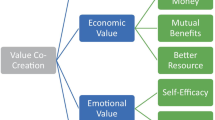

Technology-driven and knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship are more than ever indispensable for the competitiveness and survival of individuals, organisations and territories alike (Romano et al. 2016). Modern entrepreneurs boost competitiveness in the knowledge economy, because (Romano et al. 2016): they adopt or adapt existing technologies and increase the propensity for incremental innovation; strengthen social capital and innovation networks; spread knowledge and increase the actors’ capacity to absorb new knowledge. The innovative, disruptive, and transformative influence of modern entrepreneurs on the economy has also been studied within tourism, whereby Sigala (2015) showed that e-intermediaries exploiting online knowledge resources and/or technological advances have the potential to respond but also form new tourism markets (market-driven vs. driving-market e-intermediaries). By using the ‘learning with the market’ approach (Storbacka and Nenonen 2011), Sigala identified three learning capabilities through which knowledge-intensive and technology-driven intermediaries engage with tourism markets for shaping and influencing their formation: network structure referring to the firms’ ability to develop and maintain networks and ties with other market actors with the purpose to exchange resources and co-create value; market practices (exchange, normalized and representational practices) referring to the ways and the institutions that support and frame the actors’ interactions and resource exchanges; and the market pictures representing the actors’ interpretation and understanding of the market, which in turn influence their market practices. These capabilities enable the entrepreneurs to initiate change and form (new) markets by: changing the structure and operations of the economic structure and/or value chain; and engaging in (collaborative) sense-making processes that change the actors’ mental models/understanding of the markets (i.e. market pictures) and so, their market practices. The role of market structure on service ecosystems transformation and innovation is also in line with current arguments that value co-creation takes place within complex networks that go beyond dyadic resource exchanges (Chowdhury et al. 2016; Brozovic et al. 2016; Vargo and Lusch 2015). The sharing economy also represents a complex ecosystem enabling numerous actors to network and exchange resources in innovative ways, which in turn can significantly lead to disruption and innovation. Moreover, as the sharing economy redefines basic institutions and understandings of basic concepts (e.g. labour, value), these new meanings can also influence the market pictures and so, practices (behaviours) of sharing entrepreneurs that in turn can cause change and transformation.

9.4 Methodology

The study aimed to identify the entrepreneurs that have emerged around the Airbnb sharing ecosystem in order to provide services to Airbnb hosts that can facilitate and support them to provide accommodation services in a more effective and efficient way. An extensive internet search was undertaken for identifying these entrepreneurs and analysing their services. The following keywords were used in google.com and Bing.com search engines: Airbnb; services; management support; Airbnb entrepreneurs. The Airbnb Open (https://airbnbopen.com/)—an annual event organised by Airbnb for gathering and allowing all Airbnb entrepreneurs to meet, network and exchange services—has also been used for identifying Airbnb entrepreneurs. Finally, the methodology also used a snowball technique for identifying Airbnb entrepreneurs; to achieve that the researchers used her personal contacts being Airbnb hosts for naming entrepreneurs that they use, which in turn was asked to provide contacts of any other related entrepreneurial company. Since the topic is new, new entrepreneurs around the Airbnb sharing ecosystem emerge continuously and there is no list or research identifying, studying and categorising them in any way, this study had to adopt an exploratory method for locating these entrepreneurs through a wide internet research and snowballing technique. Once entrepreneurs were identified their websites were studied and/or telephone interviewed if a website was not available for understanding the services they provided. Services were categorised in themes related to management activities and operations, i.e. marketing, operations, cleaning-maintenance, security, legal and/or business consulting, distribution, pricing etc.

9.5 Analysis and Discussion of the Findings

The majority of the identified entrepreneurs operating around the Airbnb ecosystem represents start-ups providing online property management and booking systems that assist Airbnb hosts to: create their listings on Airbnb; screen guests; have an online reservation and booking system. Many other start-ups represent entrepreneurs offering offline services, such as: property decoration and design services; cleaning services; property security services; accounting and management consulting services (e.g. legal and tax services). Other entrepreneurs have developed and/or adapted an existing technology application that Airbnb hosts can use in order to: manage customer reviews; filter reservation requests by filtering guests based on their creditability, profile and reliability; determine pricing strategies; get access to educational services about the sharing economy; participate in peer-to-peer networks for exchanging knowledge and best practices with other Airbnb hosts and/or sharing economy entrepreneurs. Table 9.1 categorises the identified entrepreneurs by using the traditional value chain model (Porter 1985). Overall, these entrepreneurs provide a great variety of management services that span all the value creation stages of a value chain. By outsourcing these services to Airbnb hosts, the latter are enabled to produce a hospitality product that is very similar to the commercialised hospitality product rather than a genuine hospitality experience.

In other words, by engaging in this co-creation ecosystem, Airbnb hosts are enabled to commercialise and professionalise the accommodation services that they provide through Airbnb, which traditionally have been promoted in the literature and perceived by the citizens’ eyes as authentic and genuine hospitality experiences. Consequently, this creates a head-to-head competition between Airbnb hosts and professional hoteliers, which in turn questions the arguments supporting that the Airbnb serves and targets a totally different tourism market. The latter also reinforces the arguments and pressures to regulate the Airbnb sharing ecosystem in order to create a more equal and fair playing marketplaces for both the traditional hotels and the Airbnb accommodation providers (e.g. by taxing and requiring Airbnb hosts to acquire similar accreditation requirements as traditional hotels). From a competitive point of view, traditional hotels would also need to revisit their strategy and value proposition in order to find a way to differentiate themselves from the commercialised sharing economy accommodation product.

Finally, these entrepreneurs are creating several sub-economies of service exchanges around the Airbnb sharing platform that expand the scope and the scale of the Airbnb impact on economic systems, value chains and employment statistics as well. In this vein, studies investigating the impact of Airbnb on destinations would need to adapt a macro level of analysis in order to capture these multiplier economic and employment effects of Airbnb. Overall, these entrepreneurs redefine both the offering of the sharing accommodation sector as well as the structure and the nature of the economic value system of accommodation provision.

For providing their services and value proposition, these entrepreneurs rely on the following types of knowledge (Malerba 2010):

-

Domain knowledge: know-how of accommodation management services, expertise in the accommodation sector and in the shared economy domain

-

Organisational knowledge: knowledge about business management and service outsourcing

-

Technological knowledge: adaption of technological tools/systems/solutions, regulations, institutions etc. in the shared economy domain

The sustainability of the business model and value proposition of these entrepreneurs heavily depends on both business risks (market potential) and technology risks (Byers et al. 2011). For example, some of the entrepreneurs who were identified 1–2 years ago when the interest search was conducted (Table 9.1) may not exist anymore. As any start-up company, these success of these entrepreneurs heavily depends on the attractiveness, appeal and value proposition of their business model as well as the up-take of the sharing economy in general. All these represent business risks relating to the market potential of the shared accommodation market, the ability of the entrepreneurs to provide a solution that effectively responds to its needs, but also to shapes them. In other words, the success of these entrepreneurs also depends on the adoption of the sharing economy in general, and so, their proactive practices to institutionalise this type of shared accommodation as a ‘normal’ practice in the market can also influence their successes. Technology risks relate to the success of the technological or business propositions of these entrepreneurs to provide a solution that ‘solves’ the management issues of Airbnb hosts and enables them to do their work in a more efficient and effective way. To overcome technology risks, the technological solutions and management services provided by these entrepreneurs need to be customised to: the needs and profile of the Airbnb hosts (e.g. micro-entrepreneurs of a tiny business scale without business experience, time and knowledge resources); and the institutional context of the sharing economy (e.g. socio-cultural and legal environment). Overall, in order to survive but also become competitive, the entrepreneurs need to address both the business and technological risks by being adopting a re-active and pro-active approach in responding or shaping these market and technological trends. Consequently, entrepreneurship fuelled within the sharing economy definitely requires new skills and competencies that entrepreneurs did not have to possess some decades ago.

Table 9.2 provides another theoretical lence for interpreting the roles that these entrepreneurs adopt for forming and changing the shared accommodation market and by doing this, ensuring the sustainability of their value proposition. By adopting the ‘learning with the market’ capabilities framework, Table 9.2 explains how the entrepreneurs of the Airbnb sub-economies engage with and participate in the shared accommodation market for shaping its form. Examples of entrepreneurs that have developed each market formation capability are also provided.

Specifically, several entrepreneurs have created and provide an online marketplace/directory that enables the various actors participating in the shared economy (i.e. consumers, trading partners, outsourcers, researchers etc.) to: search and find a shared economy platform and trading actors; and list, promote and exchange their services. By enabling the various actors of the sharing economy to link with each other, form ties and connect in various ways, these entrepreneurs shape the shared economy by influencing its network structure by making it more open, transparent, flexible and fluid (i.e. actors can identify, evaluate and participate in shared ecosystems in a ‘plug-and-play mode). Entrepreneurs also engage in practices influence the norms and institutions (e.g. technology standards, social norms and values, regulations) governing and shaping the shared accommodation market. Finally, many of the practices (seminars, workshops, peer-to-peer exchange networks) developed by these entrepreneurs also influence the mental schemas (e.g. assumptions, ideas and dominating logic) of the actors participating in the shared economy, which in turn shape the way actors engage and co-create value in the shared economy. It also becomes evident that many entrepreneurs engage in more than one type of practice, which highlights that entrepreneurs possess and develop more than one learning capability for engaging with and shaping the sharing economy market. In this vein, future studies would be interesting to examine whether there is a relation between the learning capabilities and: (1) the ‘competitiveness’, long-term ‘sustainability’ and performance of the business model of these entrepreneurs; and (2) the evolution and shape of the sharing economy in terms of its institutionalization, routinization and/or integration within traditional value systems and chains.

9.6 Conclusions and Implications

Research in the sharing economy has primarily focused on the exchange actors and platforms, ignoring the various entrepreneurs emerging around sharing economy ecosystems and aiming to empower and enable actors to participate in the sharing economy. This study aimed to identify and study the value proposition and services provided by the numerous types of entrepreneurs that emerge around the Airbnb ecosystem with the purpose to provide services to Airbnb hosts that enable them to engage, shape and redefine the shared accommodation sector.

However, the findings of this study provide evidence that an increasing number of Airbnb entrepreneurs enable and facilitate citizens to ‘become’ professional accommodation entrepreneurs that can provide a service and a hospitality experience that is very similar to the commercialised hotel experience. Moreover, many of these entrepreneurs engage in market practices that influence the shape and evolution of the shared accommodation market. By doing this, the entrepreneurs do not only ensure the long-term sustainability of their business model and value proposition, but they also support the institutionalisation, routinisation and ultimately the integration of the shared accommodation sector with the traditional accommodation economy. Airbnb has been proposed as an emerging hospitality phenomenon called network hospitality and defined as (Molz 2013, p. 216) the way people “…connect to one another using online networking systems, as well as to the kinds of relationships they perform when they meet each other offline and face to face”. Airbnb represents network hospitality, as it enables a hybrid marketplace combining three domains of hospitality (namely private, commercial and social). According to this study, the sub-economies of service exchanges enabled by these entrepreneurs empower more private micro-entrepreneurs to become professional hoteliers and participate in the shared accommodation sector. However, by doing this, they also weaken the social aspect of the networked hospitality (less authentic interactions and more professional accommodation services provided for a price), while also strengthen its commercial dimension (provision of commercialised professional accommodation services and experiences for a price).

As all studies, this research has several limitations. The study represents an exploratory research focusing only on one domain of the sharing economy (i.e. accommodation) and one sharing platform (Airbnb). This study also provides the foundation but also the directions for conducting future research. For example, future studies can further examine the impact of these entrepreneurs on: motivating and empowering more and more citizens to become ‘professional hoteliers’ and participate in the commercialised accommodation sector by buying properties and outsourcing all their management services to sub-economies; inspiring micro-entrepreneurship and creating employment opportunities and jobs for unemployed and/or under-employed; the evolution and the shaping of the shared accommodation experience; and the behaviour, perceptions and satisfaction of Airbnb guests. To achieve that, future research would have to challenge our conceptualisation and definition of employment, entrepreneurship, working patterns as well as models measuring customer satisfaction and experiences.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Armington, C. (2006). Entrepreneurship, geography, and american economic growth. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Aggarwal, R., Gopal, R., Gupta, A., & Singh, H. (2012). Putting money where the mouths are: The relation between venture financing and electronic word-of-mouth. Information Systems Research, 23(3-Part-2), 976–992.

Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, A. R. (2001, March). What’s new about the new economy? Sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(1), 267–315.

Badger, A. (2013). The rise of invisible work: Companies like Airbnb and Etsy are redefining what it means to have a “job.” Is that good for the economy? http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/rise-invisible-work/7412/

Botsman, R. (2014). Sharing is not just for startups. Harvard Business Review, 92(3), 23–26.

Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2011). What’s mine is yours: How collaborative consumption is changing the way we live. New York: Harper Collins.

Brozovic, D., Nordin, F., & Kindström, D. (2016). Service flexibility: Conceptualizing value creation in service. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(6), 868–888.

Burtch, G., Carnahan, S. & Greenwood, B. (2016). Can you gig it? An empirical examination of the gig-economy and entrepreneurial activity (Ross School of Business Working Paper, working paper No. 138)

Byers, H. T., Dorf, C. R., & Nelson, J. A. (2011). Technology ventures: Management dell’imprenditorialità e dell’innovazione. Milano: McGraw-Hill.

Chowdhury, I. N., Gruber, T., & Zolkiewski, J. (2016). Every cloud has a silver lining—Exploring the dark side of value co-creation in B2B service networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 55, 97–109.

Ert, E., Fleischer, A., & Magen, N. (2016). Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tourism Management, 55, 62–73.

Fairlie, R. W. (2002). Drug dealing and legitimate self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(3), 538–537.

Fang, Y., Qureshi, I., Sun, H., McCole, P., Ramsey, E., & Lim, K. H. (2015). Trust, satisfaction, and online repurchase intention: The moderating role of perceived effectiveness of e-commerce institutional mechanisms. MIS Quarterly, 38(2), 407–427.

Fradkin, A. (2013). Search frictions and the design of online marketplaces (Tech. rep., Working paper). Stanford University.

Fradkin, A., Grewal, E., Holtz, D., & Pearson, M. (2014). Reporting bias and reciprocity in online reviews: Evidence from field experiments on Airbnb. http://andreyfradkin.com/ [20/3/2015]

Greenwood, B. N., & Agarwal, R. (2015). Matching platforms and HIV incidence: An empirical investigation of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Management Science, 62(8), 2281–2303.

Guttentag, D. (2013). Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–26.

Hall, J. V., & Krueger, A. B. (2015). An analysis of the labor market for Uber’s driver-partners in the United States. Mimeo: UCLA.

Hill, D. (2015). How much is your spare room worth? IEEE Spectrum, 52(9), 32–58.

Huston, C. (2015, August 13). As Airbnb grows, hotel prices expected to drop Market Watch. Marketwatch. www.marketwatch.com/story/as-airbnb-grows-hotel-pricesexpected-to-drop [12/12/2016].

Ikkala, T., & Lampinen, A. (2014). Defining the price of hospitality: Networked hospitality exchange via Airbnb. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, (pp. 173–176).

Koopman, C., Mitchell, M., & Thierer, A. (2014). The sharing economy and consumer protection regulation: The case for policy change. Arlington: Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Lane, J. & Woodworth, R. M. (2016). The sharing economy checks in: An analysis of Airbnb in the United States. Retrieved February 13, 2016 from http://www.cbrehotels.com/EN/Research/Pages/An-Analysis-of-Airbnb-in-the-United-States.aspx

Maeyer, C., & Bonne, K. (2015). Entrepreneurship 3.0: tools to support new and young companies with their business models. Journal of Positive Management, 6(3), 3–15.

Mahajan, N. (2015). Share. Don’t own: The sharing economy takes off. Forbes. Accessed July 1, 2016 from http://www.forbesindia.com/article/ckgsb/share.-dont-own-the-sharing-economy-takes-off/39241/1

Malerba, F. (2010). Knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship and innovation systems. Evidence from Europe. Routledge: London.

Miller, S. R. (2014). Transferable sharing rights: A theoretical model for regulating Airbnb and the short-term rental market. Available at SSRN 2514178.

Möhlmann, M. (2015). Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(3), 193–207.

Molz, J. G. (2013). Social networking technologies and the moral economy of alternative tourism: The case of couchsurfing.org. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 210–230.

Neeser, D., Peitz, M., & Stuhler, J. (2015). Does Airbnb hurt hotel business: Evidence from the Nordic countries (Master degree paper). Retrieved June 6, 2016, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David_Neeser/publication/282151529_Does_Airbnb_Hurt_Hotel_Business_Evidence_from_the_Nordic_Countries/links/5605310e08aea25fce322679.pdf

Olson, K. (2013). National study quantifies reality of the “Sharing Economy” movement. http://www.campbell-mithun.com/678_national-study-quantifies-realityof-the-sharing-economy-movement [10/9/2015]

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press.

Romano, A., Passiante, G., & Del Vecchio, P. (2016). The technology-driven entrepreneurship in the knowledge economy. In Creating technology-driven entrepreneurship (pp. 21–48). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sigala, M. (2014). Collaborative commerce in tourism: Implications for research and industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–10.

Sigala, M. (2015). From demand elasticity to market plasticity: A market approach for developing revenue management strategies in tourism. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 32(7), 812–834.

Standing, S. & Mattsson, J. (2016). Fake it until you make it: Business model conceptualization in digital entrepreneurship. Journal of Strategic Marketing. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2016.1240218

Stern, J. (2014). Airbnb Benefits from social proof theory. Retrieved February 20, 2015, from www.Josephstern.com

Storbacka, K., & Nenonen, S. (2011). Scripting markets: From value propositions to market propositions. Industrial Marketing Management, 40, 255–266.

Storey, D. J. (1991). The birth of new firms—Does unemployment matter? A review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 3(3), 167–178.

Sundararajan, A. (2014). Peer-to-peer businesses and the sharing (collaborative) economy: Overview, economic effects and regulatory issues. Available at: http://smallbusiness.house.gov/uploadedfiles/1-15-2014_revised_sundararajan_testimony.pdf

Sundararajan, A. (2016). Sharing economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Swarns, R. (2014). Freelancers in the ‘Gig Economy’ find a mix of freedom and uncertainty. New York Times, A14.

Thurik, A. R. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic growth and policy in emerging economies. ERIM report series research in management (No. ERS-2008-060-ORG). Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM). Retrieved September 10, 2016, from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/13318

Tussyadiah, I. P. (2015). An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In I. Tussyadiah & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 817–830). Cham: Springer International.

Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2015). Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. Journal of Travel Research, 1–19.

Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2016). Drivers and barriers of peer-to-peer accommodation stay – An exploratory study with American and Finnish travellers. Current Issues in Tourism, 1368–3500, 1–18.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2015). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23.

Yannopoulou, N., Moufahim, M., & Bian, X. (2013). User-generated brands and social media: Couchsurfing and AirBnb. contemporary management. Research, 9(1), 85–90.

Zekanovic-Korona, L., & Grzunov, J. (2014, May). Evaluation of shared digital economy adoption: Case of Airbnb. In Proceedings of 37th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), 2014 (pp. 1574–1579). IEEE.

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. (2015). The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry [Boston University School of Management Research Paper (2013-16)].

Zumbrun, J., & Sussman, A. L. (2015). Proof of a ‘gig economy’ revolution is hard to find. Despite the hoopla over Uber, Etsy and the sharing economy, Americans are becoming less likely to be self-employed, hold multiple jobs, data show. Wall Street Journal, 26 July, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/proof-of-a-gig-economy-revolution-is-hard-to-find-1437932539

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sigala, M. (2018). Market Formation in the Sharing Economy: Findings and Implications from the Sub-economies of Airbnb. In: Barile, S., Pellicano, M., Polese, F. (eds) Social Dynamics in a Systems Perspective. New Economic Windows. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61967-5_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61967-5_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61966-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61967-5

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)