Abstract

This chapter proposes a conceptualisation and operationalisation of human agency in work contexts based on a larger literature review. In a first step, two conceptually different perspectives of human agency are discussed: (a) agency as something individuals do and (b) agency as a personal feature of individuals. Both perspectives are then integrated into a larger framework also including situation-specific context factors. In a second step, three distinct components of human agency as a personal feature of individuals are derived and discussed: (a) agency competence (i.e. the capacity to visualise desired future states, to set goals based on these states, to translate these goals into actions, to engage in these actions, and to deal with upcoming problems), (b) agency beliefs (i.e. perceptions of whether one is agentically competent or not), and (c) agency personality (i.e. a stable and comparable situation-unspecific inclination to make choices and to engage in actions based on these choices with the aim to take control over one’s life or environment). In a third step, the results of this theoretical discussion are then used to propose an operational definition of human agency that may be used in a range of empirical studies employing hypothesis-testing methods.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Human agency

- Agency competence

- Agency beliefs

- Agency personality

- Definition

- Conceptualisation

- Operationalisation

- Proactivity

- Workplace learning

- Professional development

1 Introduction

Human agency is a commonly used concept in the literature on workplace learning (Goller 2017; Tynjälä 2013) that has been associated with—amongst other aspects—individuals’ development of professional knowledge, skills, and abilities (e.g. Billett 2011; Eraut 2007; Harteis and Goller 2014), individuals’ (re-)negotiation of work identities (e.g. Eteläpelto et al. 2014; Vähäsantanen 2013), as well as individuals’ contribution to transformations of occupational practices (Billett 2006, 2011). Across these accounts, human agency is used to explain that individuals make choices and act on these choices that affect their life courses as well as their environments (see also Eteläpelto et al. 2013). In more general terms, human agency describes how human beings are agents of influence who are able to cause things and to bring about change (Bunnin and Yu 2004; Schlosser 2015; Shanahan and Hood 2000).

Unfortunately, empirical research focussing on the concept of human agency is still scarce. Only a few empirical studies have investigated the role of human agency in professional learning and development processes (e.g. Bryson et al. 2006; Fox et al. 2010; Hökkä et al. 2012; Smith 2006; Vähäsantanen et al. 2009). Using qualitative research methods, these studies found evidence that (some) individuals indeed exercise agency at work and that human agency is strongly linked to learning and development. However, due to the methods applied in these studies, their findings are only based upon rather small numbers of participants and cannot—because of their design—be easily generalised beyond the specific samples. Quantitative studies that aim to validate and generalise these exploratory findings using larger samples and hypothesis-testing methods are still lacking.

The lack of quantitative studies might best be explained by the vagueness and abstractness of the agency discourse within the literature on workplace learning (Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Goller 2017). Many authors use the concept of human agency without providing an explicit definition (e.g. Billett 2006; Eraut 2007; Skår 2010). Without such a definition, however, it is not possible to operationalise a theoretical construct (Jaccard and Jacoby 2010). The aim of this chapter is therefore to propose a conceptualisation and definition of human agency that can be used to operationalise the construct in quantitative empirical studies. This will be done by using not only literature on workplace learning but also literature on social-cognitive psychology, life-course research, and organisational behaviour. All three latter research strands are genuinely interested in notions of human agency, derived nomological networks of antecedents and outcomes of human agency, and have already generated a large set of empirical findings concerning these nomological networks. In addition, these literature strands were found to be well integrating and complementing with the literature that originated in the workplace learning community by discussing human agency in relation to individuals’ development in general or individuals’ action within work contexts (see Goller 2017).

This chapter is structured as follows. The second section discusses human agency from two conceptually different perspectives: (a) agency as something individuals do and (b) agency as a personal feature of individuals. Both perspectives are then incorporated into a larger framework including situation-specific context factors. Section 5.3 sets out to further concretise human agency. By drawing on literature originating in social-cognitive psychology , life-course research , and organisational behaviour , three distinct components of human agency are derived. The results of this theoretical discussion are then used in Sect. 5.4 to propose an operational definition of human agency that may be used in a range of empirical studies employing hypothesis-testing methods. The chapter closes with a short discussion of the main arguments as well as a final conclusion.

2 Conceptualisations of Human Agency

Goller (2017) reviewed the literature discussing the role of human agency in the development of work-related knowledge, skills, and abilities. All discourses covered in this review emphasised the importance of human agency to explain how individuals learn and develop in work contexts. Based on this review, he identified two different idealised perspectives on agency within the discussions (agency as something individuals do and agency as a personal feature; see below). Those conceptual perspectives are not necessarily addressed by the different authors in their writings (see also Tynjälä 2013). They are, rather, implicit themes that emerge based on how human agency is used within the respective research agendas and theories. In fact, only a few authors (e.g. Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Lipponen and Kumpulainen 2011) describe an explicit understanding of agency that clearly indicates which of the two perspectives is employed in their studies. Furthermore, some authors incorporate elements of both perspectives in their notions of human agency (e.g. Billett and Smith 2006). It is therefore important to understand that the distinction into two separate perspectives is predominantly meant to be an analytical tool to understand the abstract discussion about human agency rather than a rigid framework to classify existing theoretical accounts.

Authors who mainly adopt the first perspective describe human agency as something that individuals do (e.g. Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Vähäsantanen 2013). Human agency within these writings is discussed as being manifested when individuals make choices and act based on these choices. In other words, human agency is about decisions and actions in life. These decisions and actions are then argued to be related to certain kinds of outcomes like changes in work practices, transformations of an individual’s identity, or the development of knowledge and skills. By adopting this perspective , Eteläpelto et al. (2013) proposed the following definition of human agency in work contexts: “Agency is practiced when professional subjects and/or communities exert influence, make choices and take stances in ways that affect their work and/or their professional identities” (p. 61). Typical examples of such agentic actions are when individuals proactively seek feedback and information at work (see Goller and Billett 2014; Harwood and Froehlich 2017, this volume), propose new and creative work methods or procedures (see Billett 2006, 2011; Messmann and Mulder 2017, this volume; Kreuzer et al. 2017, this volume; Wiethe-Körprich et al. 2017, this volume), deliberately work with others in order to reach some shared goals (see Edwards et al. 2017, this volume; Kerosuo 2017, this volume), as well as proactively seek out new experiences at work (see Goller and Billett 2014). It should be noted that agentic actions are not necessarily observable. The concept also includes behaviours that might not be easily observed from external perspectives (e.g. reflection).

The second perspective conceptualises human agency more as a personal feature of human beings (e.g. Bryson et al. 2006; Eraut 2007, 2010; Harteis and Goller 2014). Agency is discussed as something (i.e. an antecedent, a prerequisite, or a disposition ) that allows individuals to make choices and to engage in actions based on these choices. Incorporated in this perspective is the idea that some individuals engage more often in agentic actions than others. Harteis and Goller (2014) describe this notion with a hypothetical continuum stretching between two opposing extreme points: agentic and non-agentic individuals (see also Goller 2017; Little et al. 2006). Agentic individuals frequently exercise agency and therefore actively take control over their lives and their environments. In contrast, less or non-agentic individuals tend to react and to comply with external conditions and therefore do not actively take control over their lives and environments or do so less often. This does not necessarily mean that non-agentic individuals do not “possess” agency. It rather means that agentic individuals utilise their agency “with greater facility” (Hitlin and Elder 2007, p. 183) in comparison to their less agentic counterparts. A summary of both conceptualisations can be found in Table 5.1.

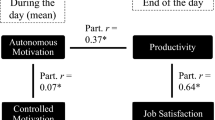

These perspectives are not necessary incompatible . In fact, both conceptions can be combined into a single theoretical framework. For this purpose, it is necessary to assign different labels to each conceptual perspective. Within this chapter, the first perspective will be referred to as agentic actions. Agentic actions describe all kind of self-initiated and goal-directed behaviours that aim to take control over the work environment and/or the acting individual’s life. The second perspective will be labelled as human agency (in a narrow sense). Human agency is then defined as the capacity and tendency to make intentional choices, to initiate actions based on these choices, and to exercise control over the self and the environment Footnote 1 (see also Eteläpelto et al. 2010; Harteis and Goller 2014). Within this definition human agency is conceptualised as a disposition . A disposition is an individual characteristic that “determines the a priori probability of adopting a particular goal and displaying a particular behaviour pattern” (Dweck and Leggett 1988, p. 269). Put differently, agentic individuals are a priori more inclined to engage in agentic actions than less or non-agentic individuals. Human agency—in this sense—is therefore understood as an antecedent of agentic behaviour that (might) eventually lead to certain kinds of outcomes . A graphical depiction of this framework can be found in Fig. 5.1.

Theoretical framework combining both conceptualisations of human agency (Reprinted and adapted from Goller (2017, p. 87) with permission from Springer VS)

It is important to note that the proposed framework and definitions do not deny that human agency (in a broad sense) can be understood either as a personal feature or as something individuals do. An attempt was made to combine both perspectives within a single framework. The two different labels (human agency in a narrow sense and agentic actions) have been assigned because of purely analytical reasons, in other words, to distinguish both perspectives within the proposed framework. Other authors might choose to refer to agentic actions as human agency and the personal feature that allow individuals to act agentically as something completely different. This is legitimate. However, it is important that authors make clear what understanding of human agency is used in their writings to avoid further confusion about the concept.

To this point, human agency has been exclusively discussed from an individual perspective. It is, however, important to note that neither of the discussed perspectives conceptualises human agency as something independent from social, cultural, historical, and physical contexts . In contrast, all authors profoundly acknowledge that human agency can only be understood in relation to the social and material world—that is, the concrete circumstances an individual faces in everyday life. All choices and actions are always influenced by what a particular context (e.g. a workplace) affords or denies its participants (Billett 2001, 2006, 2011). Such affordances or constraints are directly related to social, cultural, historical, and physical context factors (Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Elder and Shanahan 2007; Shanahan and Hood 2000; Tornau and Frese 2013).

Theoretically, context factors can be understood to alter the a priori probability of whether an individual tends to engage in an agentic action or not (see also Dweck and Leggett 1988). Some factors might inhibit the exercise of human agency, whilst others might encourage individuals to adopt an agentic behavioural approach. For instance, one supervisor might strongly constrain an agentic individual’s tendency to address tensions at work in his or her department, whilst another might strongly encourage employees—even less agentic ones—to do so. Context factors might also affect individuals’ general inclination to exercise human agency in the first place. For instance, some individuals might not have had the chance to develop the competences and inclinations to make decisions and to translate those decisions into action plans (see next section). Such individuals are less likely to exercise agency than individuals who have had the chance to develop such individual features from early on. And finally, context factors also influence the consequences of agentic actions. Some circumstances make it easier to achieve intended goals than others. Put differently, the outcome of a particular agentic action might not always be the intended one because of context factors that are not within the realm of the acting individual (see also Giddens 1984). For instance, a highly competent and qualified individual might agentically apply to a wide range of potential employers but not get a job because of an ongoing economic recession. Due to this reasoning, Fig. 5.1 depicts the chain of human agency, agentic actions, and outcomes as being embedded in the social, cultural, historical, and physical context. A more detailed discussion about the effect of context factors on human agency can be found in Goller (2017).

3 Three Facets of Human Agency

The previous section argued that some individuals engage more often in agentic actions than others. The differences between those individuals have been attributed to their capacity and tendency to make intentional choices, to initiate actions based on these choices, and to exercise control over the self and the environment (i.e. human agency as a personal feature). However, this definition does not yet explain exactly why some people are more capable and inclined to engage in agentic actions, whilst others are not. The aim of this section will therefore be to introduce three components that are suited to explain these differences: (a) agency competence , (b) agency beliefs , and (c) agency personality . Each component is strongly associated with a range of psychological mechanisms that have been discussed as relevant with regard to human agency within the literature on social-cognitive psychology, life-course research, and organisational behaviour. The next sections will shortly discuss each of these components.

3.1 Agency Competence

By exercising agency human beings always attempt to take control over their lives or the environment(s) of which they are part. Such efforts require individuals to engage in a process of self-regulation by coming up with goals, making decisions in favour of or against those goals, translating these decisions and goals into feasible action plans , constantly evaluating their own progress, and persisting in the face of challenges and obstacles. Differences in the ability to do so might therefore explain why some individuals exercise their agency more often than others.

In a very first step, individuals have to generate desired goals (Parker et al. 2010). Such goals are nothing other than cognitive representations of possible future selves or conceivable environmental states (Bandura 2001; Grant and Ashford 2008; Hitlin and Elder 2007; Cross and Markus 1991). They are concrete ideas about what kind of person one wants to be or how one’s environment (e.g. the workplace) should look in the future. These cognitive representations of desired future states work as motivators that help to energise and direct actions regardless of current circumstances (Grant and Ashford 2008; Locke and Latham 2002). It is exactly this mechanism that “enables people to transcend the dictates of their immediate environment and to shape and regulate the present to fit a desired future” (Bandura 2001, p. 7). In relation to more sociological discussions, these ideas can be interpreted as a temporal dimension of human agency (see Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Kristiansen 2014; Marshall 2005).

It is not only important, however, to be able to cognitively represent possible futures. Clausen (1991) emphasises that individuals have to be able to come up with goals that match their personal strengths and preferences. Only if individuals recognise and know about their own strengths and weaknesses as well as preferences can they avoid committing to goals that are unrealistic or just generally ill-fitting. It therefore follows that agentically competent individuals should (a) know themselves better than their less competent counterparts as well as (b) be able to generate and decide about desired goals that are strongly based upon this knowledge.

In the second step, decisions and goals have to be translated into concrete and feasible action plans (Bandura 2001, 2006; Clausen 1991; Grant and Ashford 2008; Shanahan and Elder 2002). This requires the individual to break down more general and distal goals into a hierarchically structured system of sub-goals. Such proximal sub-goals are much more likely to enfold their potential to motivate the individual to act (Bandura 2001, 2006). Distal aspirations are often too abstract to be translated into step-by-step action plans and thereby possess less motivational potential. Action plans describe concrete strategies to meet each of the single sub-goals that have been derived by the individual (Grant and Ashford 2008). This can be done by anticipating potential outcomes of possible actions and consequently selecting the one(s) that are most likely to produce the desired outcomes connected to lowest possible costs (Bandura 2001).

In the third step, the individual has to implement his or her action strategy and constantly monitor whether the chosen behaviours indeed contribute towards the achievement of the sub-goals as well as the more distal desired future state (Bandura 2001, 2006). Especially in the face of obstacles and challenges, individuals need either to exhibit persistence or to find new strategies to handle the encountered problems (Pintrich 2005). In addition, individuals also have to resist the momentary urges and needs that are not in line with the chosen long-term goals (Baumeister and Vohs 2007, 2012). Successful regulation includes either the postponement or negligence of such distractions.

To sum up, human beings are more likely to engage in self-initiated and goal-directed behaviours if they are able to visualise desired future states, to set goals based on these states, to translate these goals into actions, to engage in these actions, and to deal with problems that might occur. This requirement of human agency will be subsumed under the concept of agency competence. Agency competence —that is, the competence to initiate and engage in agentic actions—is assumed to be the first crucial component of human agency as a personal feature.

3.2 Agency Beliefs

The ability to make choices, to engage in agentic actions, and to persist in the face of obstacles is not sufficient to explain why some individuals exercise more agency than others. Some individuals might indeed be agentically competent but still do not engage in any agentic actions. One possible reason for this phenomenon is the absence of agency beliefs —that is, an individual’s subjective perception about whether or not she or he has the abilities to exercise agency.

A central assumption of Bandura’s (2001, 2006) social-cognitive theory is that human beings are inherently able and inclined to reflect upon their own capabilities to initiate actions and to exercise control over their life and environment. In his opinion, human beings generally examine whether they are capable of successfully executing the behaviour in question and whether they are likely to produce the targeted outcome before engaging in any kind of action (Bandura 1977, 1986; Parker et al. 2010; see also, for a more general discussion of such control beliefs, Skinner 1995, 1996). Based on this argumentation, it is necessary to possess not only the abilities to exercise agency but also the beliefs in oneself to do so in the first place. For “[u]nless people believe they can produce desired results and forestall detrimental ones by their actions, they have little incentive to act or to persevere in the face of difficulties” (Bandura 2001, p. 10). Such kinds of expectations are summarised in the concept of (self-)efficacy beliefs .

A range of studies has found empirical evidence that self-efficacy beliefs are indeed positively related to self-initiated and goal-directed behaviour. For instance, strong self-efficacy beliefs significantly and positively predict job search behaviour (Kanfer et al. 2001), a range of work-related agentic actions (e.g. career-related choices, propensity to change processes at work) and behavioural intentions (e.g. considering career choices) (Sadri and Robertson 1993), as well as college major choices and the utilisation of development-related situations (Lent and Hackett 1987). In addition, evidence exists that individuals with strong self-efficacy beliefs tend to set higher goals and are able to persist more often in the face of challenges than individuals who are less strongly convinced of their abilities to engage in agentic actions (e.g. Bandura 1977, 1978, 1986; Multon et al. 1991; Schunk 1981).

Self-efficacy beliefs are conceptualised as a malleable concept (Bandura 1977, 1982, 1986; Gist and Mitchell 1992). In other words, existing self-efficacy beliefs can both develop and deteriorate. Bandura (1986) suggested four different factors that determine such development processes: (a) mastery experiences (i.e. own experiences), (b) vicarious experience (i.e. experience of other people), (c) verbal persuasion, and (d) physical arousal like anxiety. Mastery experiences—in the sense of performance accomplishments—have been described as the most important factor of these four (Bandura 1977; Gecas 2003). Individuals who have experienced themselves as highly effective in engaging in certain kinds of behaviours within particular contexts in the past are more likely to engage again in those tasks in the future. At the same time, individuals who have not had such experiences are more likely to feel powerless and helpless (Gecas 2003; Seligman 1972, 1992). Such a sense of inefficacy is the reason why those individuals tend not to initiate agentic actions in the first place.

Judgements about one’s own self-efficacy are not necessarily accurate. Some individuals tend to underestimate and some to overestimate their abilities to engage in particular behaviours. Bandura (1986, 1997) argues that self-efficacy beliefs that are slightly above real abilities are desirable. Individuals who slightly overestimate their abilities tend to initiate actions they are not yet able to do. This might then lead either to failure because of incompetence or to success by chance. Either way, both kinds of experiences offer the potential to acquire knowledge and skills to successfully engage in the same or a similar action in the future (Bandura 1997; Linnenbrink and Pintrich 2003; see, for a discussion on the value of negative knowledge based on mistakes, Oser et al. 2012). At the same time, however, it has to be emphasised that repeated failure can easily lower individuals’ self-efficacy beliefs and therefore also reduce the likelihood of engaging in the behaviour in question in the long run (Bandura 1986; Schunk and Pajares 2009).

To sum up, individuals who strongly believe in their abilities to engage in self-initiated and goal-directed behaviour are more likely to exercise their agency than individuals who do not have such beliefs. Agency beliefs —that is, individuals’ personal perceptions of whether or not they have the abilities to engage in agentic actions—are therefore hypothesised to be another crucial component of human agency.

3.3 Agency Personality

Both agency competence and agency beliefs cover only whether an individual is able to engage in agentic actions and whether an individual believes to actually have those abilities. In the terminology of Parker et al. (2010), both facets can be described as “can do” motivational states . Such “can do” states are necessary but not sufficient to explain why some individuals engage in agentic behaviours, whilst others do not. Individuals also require a reason to do so (Parker et al. 2010). Reasons to engage in self-initiated and goal-directed behaviours are endlessly manifold. They range from the fulfilment of pressing needs, through expectations that the behaviour in question is connected to a more distal kind of desired outcome, to expected joy over the action itself (e.g. Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2000). Many of these reasons are specific either to a certain situation an individual is in or to a certain behaviour that an individual might plan to initiate. However, Sect. 5.2 defined human agency (in a narrow sense) as a general tendency or disposition to initiate goal-directed actions to take control over the self or the environment. This definition therefore requires a stable and situation-unspecific reason to engage in such behaviour that differs across individuals. In other words, this definition calls for an agency personality trait (Pincus and Ansell 2013).

Within the organisational behaviour literature, notions of human agency have been mostly discussed under the concept of proactivity —that is, all kind of “self-starting, future oriented behaviour that aims to bring about change in one’s self or the situation” (Bindl and Parker 2011, p. 567; see also Grant and Ashford 2008; Parker and Bindl 2017; Parker and Collins 2010; Tornau and Frese 2013). Within these discussions, two conceptualisations of an agency-related personality trait were developed: proactive personality and personal initiative personality. Proactive personality is defined as “a personal disposition toward proactive behavior, defined as the relatively stable tendency to effect environmental change” (Bateman and Crant 1993, p. 103), whilst personal initiative is defined as “a behaviour syndrome that results in an individual taking an active and self-starting approach to work goals and tasks and persisting in overcoming barriers and setbacks” (Fay and Frese 2001, p. 97). Both concepts are conceptually very similar, and Fay and Frese (2001) as well as Tornau and Frese (2013) found evidence that this conceptual overlap can also be confirmed empirically.

A range of studies used either proactive personality or personal initiative personality as an antecedent of a variety of different agentic actions like initiating constructive change at work, making constructive suggestions for change, seeking work-related feedback or information, professional networking, or managing one’s own career (e.g. Parker and Collins 2010; Seibert et al. 2001; Thompson 2005). Two recent meta-analyses found strong evidence that individuals with an agentic personality trait are indeed more often engaged in such kinds of agentic actions (Fuller and Marler 2009; Tornau and Frese 2013). Another study showed that proactive personality is positively and significantly related to the motivation to learn (Major et al. 2006). Maybe most interestingly, this study also showed that proactive personality explained significantly more variance in the motivation to learn than the most widely accepted comprehensive model of personality (i.e. the Big Five: Costa and McCrae 1992). In other words, evidence was found that a trait-like tendency to act agentically exists and it cannot be completely explained by existing personality dimensions like extroversion, openness to experience, neuroticism, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

Desire for control has been discussed as another plausible personality trait that explains differences regarding individuals’ tendency to exercise agency (e.g. Ashford and Black 1996; Crant 2000; Parker et al. 2010; Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001). The concept can be defined as a relatively stable inclination of a person to take control over events in her or his life (Burger and Cooper 1979) and is conceptually related to White’s (1959) idea of effectance motivation. The empirical study of Ashford and Black 1996 found evidence that newcomers in organisations, with a strong desire for control, tend to more often intentionally seek information, deliberately socialise with new colleagues, and actively expand their professional network than newcomers with a less strong desire for control. The advantage of the concept of desire for control in comparison to proactive personality or personal initiative personality is that it explains why exactly individuals tend to act agentically: because they have an innate need to control their environments and their life courses. Both earlier discussed personality traits rather define the trait by its behavioural tendency alone.

To sum up, empirical evidence exists that differences between individuals’ tendency to exercise their agency can be traced back to differences in their personality. It is exactly such an agentic personality that causes individuals to engage in agentic actions. Agency personality will therefore be defined as the stable and comparably situation-unspecific inclination to make choices and to engage in actions based on these choices with the aim of taking control over one’s life or environment (see also Goller 2017). Agency personality is hypothesised to be the third and last component of human agency as a disposition.

4 Modelling and Operationalising Human Agency as a Multifaceted Construct

Three distinct components as well as associated psychological mechanisms have been proposed to explain why some individuals engage more often than others in self-initiated behaviours aiming to take control over their selves and the environments: (a) agency competence , (b) agency beliefs , and (c) agency personality . It is now suggested that these components can be used to model and operationalise human agency. A graphical representation of this model can be found in Fig. 5.2.

The three components are understood as different facets of human agency that equivalently predict why one person tends to engage in agentic actions and why someone else does not. In this sense, human agency is modelled as a more distal and global predictor of human behaviour (Kanfer 1990, 1992). It is assumed that individuals who are agentically competent, who believe in their agency competences, and who feature a strong agency personality tend to—on average—take more often control over their lives and their environment in a large range of situations than individuals without these characteristics. However, theoretically it has still to be acknowledged that situation-specific circumstances (i.e. social, physical, cultural, and historical context factors; see Sect. 5.2) might alter the a priori probability that an individual will actually engage in any kind of particular agentic action during his or her life course. It can therefore not be expected that a measure of human agency based on this conceptualisation will result in perfect accuracy to predict agentic behaviours in an empirical study. However, it is hypothesised that it should explain a significant amount of the variance of goal-directed and self-initiated behaviours of individuals who aim to take control over their lives and their environments.

First evidence for the validity of the proposed model of human agency was presented by Goller (2017). He used the three facets to operationalise human agency as a formative latent second-order construct. In a first step, each of the facets was measured with five reflective indicators. The employed measures (agency competence, self-developed scale; agency beliefs, work-specific self-efficacy beliefs, adapted items from Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995; agency personality, need for control in work settings, adapted items from Jacobi et al. 1986) exhibited sufficient psychometric qualities including discriminant validity. In a second step, human agency was then latently measured as a linear combination of these three facets (Bollen and Lennox 1991; Jarvis et al. 2003) within a variance-based structural equation modelling approach (Esposito Vinzi et al. 2010; Hair et al. 2014). In his study, Goller (2017) could show that this agency measure significantly and positively predicted geriatric care nurses’ engagement in different agentic actions : deliberate participation in institutionalised learning activities like training; deliberate crafting of new experiences at work, deliberate enquiry of codified information through reading journals, books, or web resources; and deliberate efforts to initiate constructive change at work. This result remained robust across two different samples (n A = 432; n B = 447). Human agency explained between 7 and 27% of the variance of these agentic actions in the first and between 16 and 39% in the second sample. In addition, it could be shown that some of these agentic actions were significantly and positively related to a measure of expertise. The findings of Goller (2017), therefore, speak much in favour of the theoretical framework proposed in Sect. 5.2 as well as the predictive value of the three facets proposed in this as well as the last section.

It is important to note that human agency as conceptualised and modelled in this chapter is something that can—in part—be developed. Both agency competence and agency beliefs are defined as malleable facets of human agency. Only agency personality is assumed to be rather stable and immutable. Individuals who lack agency competence can attempt to increase their knowledge about themselves as well as to improve their abilities to make decisions, to break down goals into sub-goals, and to come up with feasible action plans that help to meet these sub-goals. This can be done by taking part in designated training, coaching, supervision or counselling sessions, as well as a range of other intrsospective activities (e.g. Jack and Smith 2007; Kombarakaran et al. 2008; Mensmann and Frese 2017; Wilson and Dunn 2004). Similarly, agency beliefs can be developed through therapeutic sessions and designated trainings, as well as upcoming mastery experiences (Bandura 1986; Gecas 2003; see also Eden and Aviram 1993; Gist 1989; Gist and Mitchell 1992). It therefore follows that societies or even single employing organisations that highly endorse individuals’ attempts to take charge of their lives as well as of their environments are advised to offer access to corresponding development opportunities. A description and discussion of such a development opportunity aiming at the promotion of human agency within professional contexts can be found in Vähäsantanen et al. (2017, this volume).

5 Summary and Conclusion

Although the term human agency has been commonly used within the workplace learning literature, empirical research, including the concept and which employs hypothesis-testing methods, is still largely lacking. One reason for this absence of research might be found in the rather abstract and vague discussion about human agency that has not yet come up with an operational definition of the concept. The aim of this chapter therefore has been to define agency in such a way that it can be operationalised for use in prospective empirical studies.

In a first step, this chapter proposed that two different notions of human agency are used in the workplace learning literature. The first notion describes agency as something individuals do: Exercising human agency is always connected to individuals’ choices and actions that aim to take control over their life or their environments. In contrast, the second notion conceptualises human agency as a personal feature of human beings that allows them to make these choices and to engage in actions based on those choices. In this sense, the second notion describes human agency as an antecedent of the choices and actions that are part of the first notion. It was therefore proposed that both notions can be integrated into a single theoretical framework. For this purpose, human agency (in a narrow sense) was defined as the capacity and tendency to make intentional choices, to initiate actions based on these choices, and to exercise control over the self and the environment. Concrete choices and actions that are a result of this capacity and tendency are described as agentic actions. Agentic actions are defined as all kinds of self-initiated and goal-directed behaviours that aim to take control over the work environment and/or the acting individual’s life.

It is important to note that this distinction between human agency and agentic actions is explicitly not meant to say that scholars who adopted the first notion (i.e. agency as something individuals do) are incorrect in describing their perspective as human agency. It is rather used to distinguish both perspectives and to incorporate them into a single framework within this contribution. In addition, the proposed distinction might help scholars from different backgrounds to discuss more concretely their specific understanding of human agency by referring to either or both notions.

In a second step, it was proposed that the capacity and tendency to exercise agency can be modelled with three components: agency competence, agency beliefs, and agency personality. Individuals who are agentically competent, who believe in their abilities to engage in agentic actions, and who are inclined to take control over their self and their environment are hypothesised to exercise their agency more often than individuals who do not feature those characteristics. Based on this argumentation, it was suggested that these three components can be interpreted as facets of human agency that are suited to operationalise the concept.

A first study by Goller (2017) that employed these three facets to operationalise human agency in the context of work was briefly introduced. The study found early evidence about the predictive value of such an agency measure in the domain of geriatric care nursing: Human agency was positively and significantly related to a range of different self-initiated and goal-directed behaviours. However, it is still completely unclear whether the measure exhibits similar predictive qualities in other domains or with other agentic actions than the ones used in the study. It would therefore be interesting to employ the proposed agency measure in studies that, for instance, also measure individuals’ intrapreneurship behaviour (see Kreuzer et al. 2017, this volume; Wiethe-Körprich et al. 2017, this volume). In addition, it would be interesting to investigate the relationship between this measure and measures of proactive personality (Bateman and Crant 1993), personal initiative personality (Fay and Frese 2001), or Raemdonck et al.’s (2017, this volume) concept of self-directedness. Self-directedness is defined as an inclination to “self-direct work-related learning processes, that is to steer and take responsibility in diagnosing learning needs and setting goals, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies and evaluating and adjusting the learning process” (Raemdonck et al. 2017, this volume p. 402). In this sense self-directedness can be interpreted as an agentic approach towards work-related learning. The proposed measure of agency should be empirically related to all three of the named concepts.

It is hoped that the proposed conceptualisation of human agency as well as its operationalisation promotes new empirical studies concerned with this phenomenon. In general, it would be highly desirable if research on workplace learning conceptualises and operationalises key concepts in such a way that hypothesis-testing methods can be applied. The employment of hypothesis-testing methods helps to further clarify the role and relevance of highly debated concepts for the explanation of learning and development processes in work contexts. In addition to qualitative research, they help to generate more generalisable findings about how phenomena like human agency are suited to explain the development of work-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes beyond a particular sample.

Notes

- 1.

This definition is largely compatible with the definition proposed by Eteläpelto et al. (2013). However , Eteläpelto et al. (2013) do not conceptualise agency as a tendency and disposition but rather as something individuals’ do. The definition proposed in this chapter therefore shifts the focus more towards human agency as a personal feature by still being grounded within current discourses of the workplace learning literature.

References

Ashford, S. J., & Black, J. S. (1996). Proactivity during organizational entry: The role of desire for control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 199–214. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.199

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33(4), 344–358. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.33.4.344

Bandura, A. (1982). The self and mechanisms of agency. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 1, pp. 3–39). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118. http://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140202

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 115–128. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Self-regulation and the executive function of the self. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 180–197). New York: Guilford.

Billett, S. (2001). Learning through work: Workplace affordances and individual engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 13(5), 209–214. http://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005548

Billett, S. (2006). Relational interdependence between social and individual agency in work and working life. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 13(1), 53–69. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1301_5

Billett, S. (2011). Subjectivity, self and personal agency in learning through and for work. In M. Malloch, L. Cairns, K. Evans, & B. O’Conner (Eds.), The international handbook of workplace learning (pp. 60–72). London: Sage.

Billett, S., & Smith, R. (2006). Personal agency and epistemology at work. In S. Billett, T. Fenwick, & M. Somerville (Eds.), Work, subjectivity and learning (pp. 141–156). Dordrecht: Springer.

Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. (2011). Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 2: Selecting and developing members for the organization (pp. 567–598). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 305–314. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305

Bryson, J., Pajo, K., Ward, R., & Mallon, M. (2006). Learning at work: Organisational affordances and individual engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(5), 279–297. http://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610674962

Bunnin, N., & Yu, J. (2004). The Blackwell dictionary of Western philosophy. Malden: Blackwell Pub.

Burger, J. M., & Cooper, H. M. (1979). The desirability of control. Motivation and Emotion, 3(4), 381–393. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994052

Clausen, J. S. (1991). Adolescent competence and the shaping of the life course. American Journal of Sociology, 96(4), 805–842.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(6), 653–665. http://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462. http://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304

Cross, S., & Markus, H. (1991). Possible selves across the life span. Human Development, 34(4), 230–255. http://doi.org/10.1159/000277058

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Eden, D., & Aviram, A. (1993). Self-efficacy training to speed reemployment: Helping people to help themselves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3), 352–360. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.3.352

Edwards, A., Montecinos, C., Cádiz, J., Jorratt, P., Manriquez, L., & Rojas, C. (2017). Working relationally on complex problems: Building the capacity for joint agency in new forms of work. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 229–247). Cham: Springer.

Elder, G. H., & Shanahan, M. J. (2007). The life course and human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology. Hoboken: Wiley.

Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. http://doi.org/10.1086/231294

Eraut, M. (2007). Learning from other people in the workplace. Oxford Review of Education, 33(4), 403–422. http://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701425706

Eraut, M. (2010). The balance between communities and personal agency: Transferring and integrating knowledge and know-how between different communities and contexts. In N. Jackson (Ed.), Learning to be professional through a higher education e-book (pp. 1–20). Guildford: Surrey Centre for Excellence in Professional Training and Education.

Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W. W., Henseler, J., & Wang, H. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications. Berlin: Springer.

Eteläpelto, A., Hökkä, P., Vähäsantanen, K., & Collin, K. (2010). Recent notions of agency: Towards reconceptualising professional agency at work. Presentation held at SIG-14 Conference. Munich.

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2014). Identity and agency in professional learning. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (pp. 645–672). Dordrecht: Springer.

Fay, D., & Frese, M. (2001). The concept of personal initiative: An overview of validity studies. Human Performance, 14(1), 97–124. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1401_06

Fox, A., Deaney, R., & Wilson, E. (2010). Examining beginning teachers’ perceptions of workplace support. Journal of Workplace Learning, 22(4), 212–227. http://doi.org/10.1108/13665621011040671

Fuller, B., & Marler, L. E. (2009). Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 329–345. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008

Gecas, V. (2003). Self-agency and the life course. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 369–388). New York: Springer.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gist, M. E. (1989). The influence of training method on self-efficacy and idea generation among managers. Personnel Psychology, 42(4), 787–805. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1989.tb00675.x

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. B. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of Its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183–211. http://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1992.4279530

Goller, M. (2017). Human agency at work: An active approach towards expertise development. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Goller, M., & Billett, S. (2014). Agentic behaviour at work: Crafting learning experiences. In C. Harteis, A. Rausch, & J. Seifried (Eds.), Discourses on professional learning: On the boundary between learning and working (pp. 25–44). Dordrecht: Springer.

Grant, A. M., & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 3–34. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equations modeling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Harteis, C., & Goller, M. (2014). New skills for new jobs: Work agency as a necessary condition for successful lifelong learning. In S. Billett, T. Halttunen, & M. Koivisto (Eds.), Promoting, assessing, recognizing and certifying lifelong learning: International perspectives and practices (pp. 37–56). Dordrecht: Springer.

Harwood, J., & Froehlich, D. E. (2017). Proactive feedback-seeking, teaching performance, and flourishing among teachers in an international primary school. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 425–444). Cham: Springer.

Hitlin, S., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Agency: An empirical model of an abstract concept. Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 33–67. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(06)11002-3

Hökkä, P., Eteläpelto, A., & Rasku-Puttonen, H. (2012). The professional agency of teacher educators amid academic discourses. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 38(1), 83–102.

Jaccard, J., & Jacoby, J. (2010). Theory construction and model-building skills: A practical guide for social scientists. New York: Guilford Press.

Jack, K., & Smith, A. (2007). Promoting self-awareness in nurses to improve nursing practice. Nursing Standard, 21(32), 47–52. http://doi.org/10.7748/ns2007.04.21.32.47.c4497

Jacobi, C., Brand-Jacobi, J., Westenhöfer, J., & Weddige-Diedrichs, A. (1986). Zur Erfassung von Selbstkontrolle. Entwicklung einer deutschsprachigen Form des Self-Control-Schedule und der Desirability of Control Scale [About the measurement of self-control. Development of German form of the self-control schedule and the desirability of control scale]. Diagnostica, 32(3), 229–247.

Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 199–218. http://doi.org/10.1086/376806

Kanfer, R. (1990). Motivation theory and industrial/organizational psychology. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 75–170). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Kanfer, R. (1992). Work motivation: New directions in theory and research. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 1–53). London: Wiley.

Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: A personality-motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 837–855. http://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.5.837

Kerosuo, H. (2017). Transformative agency and the development of knotworking in building design. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 331–349). Cham: Springer.

Kombarakaran, F. A., Yang, J. A., Baker, M. N., & Fernandes, P. B. (2008). Executive coaching: It works! Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 60(1), 78–90. http://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.60.1.78

Kreuzer, C., Weber, S., Bley, S., & Wiethe-Körprich, M. (2017). Measuring intrapreneurship competence as manifestation of work agency in different educational settings. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 373–399). Cham: Springer.

Kristiansen, M. H. (2014). Agency as an empirical concept. An assessment of theory and operationalization (NIDI working paper no. 2014/9) (pp. 1–36). The Hague: NIDI.

Lent, R. W., & Hackett, G. (1987). Career self-efficacy: Empirical status and future directions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 30(3), 347–382. http://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90010-8

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137. http://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308223

Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 812–819. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001

Little, T. D., Snyder, C. R., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2006). The agentic self: On the nature and origins of personal agency across the lifespan. In D. Mroczek & T. D. Little (Eds.), Handbook of personality development (pp. 61–80). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. http://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.57.9.705

Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the big five to motivation to learn and development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 927–935. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.927

Marshall, V. W. (2005). Agency, events, and structure at the end of the life course. Advances in Life Course Research, 10, 57–91. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(05)10002-1

Mensmann, M., & Frese, M. (2017). Proactive behavior training: Theory, design, and future directions. In S. Parker & U. K. Bindl (Eds.), Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations (pp. 434–468). New York: Routledge.

Messmann, G., & Mulder, R. H. (2017). Proactive employees: The relationship between work-related reflection and innovative work behaviour. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 141–159). Cham: Springer.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.1.30

Oser, F. K., Näpflin, C., Hofer, C., & Aerni, P. (2012). Towards a theory of negative knowledge (NK): Almost-mistakes as drivers of episodic memory amplification. In J. Bauer & C. Harteis (Eds.), Human fallibility: The ambiguity of errors (pp. 53–70). Dordrecht: Springer.

Parker, S., & Bindl, U. K. (Eds.). (2017). Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations. New York: Routledge.

Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. (2010). Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(3), 633–662. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308321554

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

Pincus, A. L., & Ansell. (2013). Interpersonal theory of personality. In I. B. Weiner, T. Millon, & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (2nd ed., pp. 209–229). Hoboken: Wiley.

Pintrich, P. R. (2005). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 452–502). San Diego: Academic Press.

Raemdonck, I., Thijssen, J., & de Greef, M. (2017). Self-directedness in work-related learning processes. Theoretical perspectives and development of a measurement instrument. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 401–423). Cham: Springer.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sadri, G., & Robertson, I. T. (1993). Self-efficacy and work-related behaviour: A review and meta-analysis. Applied Psychology, 42(2), 139–152. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1993.tb00728.x

Schlosser, M. (2015). Agency. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/agency/

Schunk, D. H. (1981). Modeling and attributional effects on children’s achievement: A self-efficacy analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73(1), 93–105. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.1.93

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2009). Self-efficacy theory. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 35–53). New York: Routledge.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor: Nfer-Nelson.

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology, 54(4), 845–874. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00234.x

Seligman, M. E. P. (1972). Learned helplessness. Annual Review of Medicine, 23(1), 407–412. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203

Seligman, M. E. P. (1992). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Shanahan, M. J., & Elder, G. H. (2002). History, agency, and the life course. In L. J. Crockett (Ed.), Agency, motivation, and the life course: Volume 48 of the Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 145–186). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Shanahan, M. J., & Hood, K. E. (2000). Adolescents in changing social structures: Bounded agency in life course perspective. In L. J. Crockett & R. K. Silbereisen (Eds.), Negotiating adolescence in times of social change (pp. 123–134). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skår, R. (2010). How nurses experience their work as a learning environment. Vocations and Learning, 3(1), 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-009-9026-5

Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived control, motivation, & coping. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549–570. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

Smith, R. (2006). Epistemological agency in the workplace. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 157–170. http://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654586

Thompson, J. A. (2005). Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 1011–1017. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.1011

Tornau, K., & Frese, M. (2013). Construct clean-up in proactivity research: A meta-analysis on the nomological net of work-related proactivity concepts and their incremental validities. Applied Psychology, 62(1), 44–96. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00514.x

Tynjälä, P. (2013). Toward a 3-P model of workplace learning: A literature review. Vocations and Learning, 6(1), 11–36. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-012-9091-z

Vähäsantanen, K. (2013). Vocational teachers’ professional agency in the stream of change. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House.

Vähäsantanen, K., Saarinen, J., & Eteläpelto, A. (2009). Between school and working life: Vocational teachers’ agency in boundary-crossing settings. International Journal of Educational Research, 48(6), 395–404. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2010.04.003

Vähäsantanen, K., Paloniemi, S., Hökkä, P., & Eteläpelto, A. (2017). An agency-promoting learning arena for developing shared work practices. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 351–371). Cham: Springer.

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66(5), 297–333. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0040934

Wiethe-Körprich, M., Weber, S., Bley, S., & Kreuzer, C. (2017). Intrapreneurship competence as a ‘manifestation’ of work agency – A systematic literature review. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 37–65). Cham: Springer.

Wilson, T. D., & Dunn, E. W. (2004). Self-knowledge: Its limits, value, and potential for improvement. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 493–518. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141954

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. http://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Goller, M., Harteis, C. (2017). Human Agency at Work: Towards a Clarification and Operationalisation of the Concept. In: Goller, M., Paloniemi, S. (eds) Agency at Work. Professional and Practice-based Learning, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-60942-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-60943-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)