Abstract

Socially oriented organizations, such as social ventures and nonprofit organizations, fill the gap between the public sector and the private sector and alleviate the unsolved social pains. Socially oriented organizations can internationalize their operations, but international business scholars knew little about internationalization of socially oriented organizations and its determinants. Based on a data set of 271 socially oriented organizations from 63 countries, we explored the impacts of three potential determinants: (1) the organizational form, whether the socially oriented organization is economically sustainable; (2) the social nature, which types of social interventions that the socially oriented organization conducts and (3) the strength of institutional environment in the home country. The findings of this chapter enriched our previously limited knowledge on the internationalization of socially oriented organizations.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

The world economy has experienced solid growth in the last quarter century, but this growth has evidently not eradicated poverty and income inequality (Ahlstrom 2010; Alvarez et al. 2015). A large portion of the world’s population, between two and four billion people, lives on the equivalent of less than two US dollars per day (World Bank 2012). Income inequality even increased in most Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in the new millennium (OECD 2011), and neither the government nor the market can fully resolve social pains, such as global poverty, endemic disease, homelessness, famine and pollution. Socially oriented organizations, such as nonprofit organizations (Stiglitz 2006; Boli and Thomas 1997) and social ventures (Zahra et al. 2008, 2014), have, thus, increasingly stepped in to fill the gap between the public sector and the private sector and address the pervasive social pains (Teegen et al. 2004).

The above-noted socially oriented organizations and social ventures are known to be capable of tackling social problems and making an impact at the global level. International business scholars have nevertheless long ignored the phenomenon of the internationalization of socially oriented organizations. The classic research realm of international business (IB) was limited to firms of the private sector, which were considered to be exclusively profit oriented in line with the post-war organization ontology (Teegen et al. 2004). Despite this disregard in IB, there have been studies on the internationalization of socially oriented organizations in other fields of business and management, such as nonprofit management and nonprofit marketing. However, most of those studies focused on how socially oriented organizations, especially nonprofit organizations, interacted with the institutional context in the home or host country and other actors embedded in the same institutional context, such as governments, firms and inter-governmental organizations (London and Hart 2004; Teegen et al. 2004; Rondinelli and London 2003). Existing theories of the internationalization of socially oriented organizations focused on explaining how socially oriented organizations behave in the global context (such as international markets) rather than why socially oriented organizations internationalized. Business scholars know little about the determinants of the internationalization of socially oriented organizations.

This chapter aims to add to the limited extant knowledge on the internationalization of socially oriented organizations by exploring the determinants or predictors of likely internationalization, using a data set of 271 socially oriented organizations from 63 countries. More specifically, we examined the extent to which the organizational form, social nature and home country institutional environment of a socially oriented organization might predict its likelihood of internationalization. After reviewing existing theories of social entrepreneurship (SE), sustainability and nonprofit management, we selected different types of social interventions typically undertaken by socially oriented organizations as explanatory variables. Subsequent analysis showed that socially oriented organizations that conduct social interventions aimed at improving beneficiaries’ satisfaction with employment opportunities and employment conditions were less likely to be international than socially oriented organizations that do not. Socially oriented organizations that conduct social interventions to improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with formal and informal education, natural and communal environment, physical and mental health, or access to physical resources such as clean water, energy and housing were more likely to be international than socially oriented organizations that do not. We also found that nonprofit organizations do not differ significantly from social ventures in terms of likelihood of internationalization and that stronger and better-developed institutions in the home country provided better institutional support to the internationalization of socially oriented organizations.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Two Types of Socially Oriented Organizations and Their Internationalization

The global business environment nowadays is different from that of the 1990s and earlier, when most existing theories of internationalization of ventures were introduced. The evaluation of an organization’s performance has changed, as indicated by the notion of “triple bottom line” (Norman and MacDonald 2004): the public evaluates an organization’s contribution to the society by not only its financial performance but also its performance in the social and environmental domains. Social and environmental damages caused by organizations, such as economic recession, unemployment, disposition to crime, civil discord, environmental pollution and waste of non-renewable resources, are considered to be social and environmental costs with negative effects.

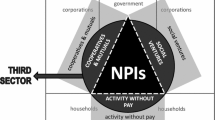

Value creation within organizations has also changed, in line with the changes in the evaluation standard for organizational performance. Value creation within organizations has shifted to the creation of blends of economic, social (societal) and environmental values (Emerson 2003), instead of a traditional exclusive focus on the creation of economic value. Academic understandings of value creation have deepened in recent years with the development of the academic fields of SE and sustainability: the ultimate goal of social entrepreneurial activities in socially oriented organizations is to create social benefits contributing to the overall well-being of the society (Kroeger and Weber 2015). The term “social”, inherited from the concept of social benefits (Gonzalez et al. 2002), was used in the field of SE and nonprofit management to generalize for value other than economic profit for the entrepreneur (Kroeger and Weber 2015). The new broad concept of social value in the context of SE and sustainability includes not only non-economic gains to the society and community (a narrow definition of social or societal value) and the environment (environmental value) but also economic gains to individuals other than the entrepreneur (Shepherd and Patzelt 2011; Patzelt and Shepherd 2011) (Table 9.1).

According to the traditional post-war ontology of organizations, ventures in the private sector are considered to be profit oriented that often cause social and environmental damages with negative effects (Teegen et al. 2004). There is an emerging phenomenon that some ventures can actively create social and environmental wealth, which positively contributes to the overall well-being of the society (or the community) (Stiglitz 2010), instead of wrecking social and environmental damages with negative effects. Those ventures that focus on creating blends of economic and social values and contributing to the overall well-being of the society or community are named as social ventures (Zahra et al. 2009, 2014).

Social ventures were theoretically predicted to be able to internationalize (Zahra et al. 2008). Some entrepreneurial opportunities that aim at social change (e.g. to fill the global poverty gap) or environmental sustainability (e.g. to fight against climate change and energy depletion) are inherently of international nature and embedded in the transnational context (Zahra et al. 2008, 2014). Social ventures, in which those opportunities are pursued, would inevitably have border-crossing business activities. Although the internationalization of social ventures had been recognized and regarded as different from the internationalization of profit-oriented ventures, empirical evidence on the internationalization of social ventures is still scarce in the existing IB literature, especially before 2014 (Zahra et al. 2014; Stephan et al. 2015; Audretsch 2015; Ghauri et al. 2014; Roy and Goll 2014).

Nonprofit organizations are a different form of socially oriented organizations, which also aim at creating social value and have been long known to be capable of internationalizing their operations (Stiglitz 2006, 2010; Boli and Thomas 1997). Nonprofit organizations follow a nonprofit mechanism, which relies on inflow of external funding, such as public funds and philanthropic donations. Once the inflow of external funding ceases, the nonprofit mechanism stops working (Yunus 2007). Nowadays, nonprofit organizations also face market pressure and competition for limited resources (Alexander and Weiner 1998; Andreasen and Kotler 2003). As a consequence, they have started to adopt business-like techniques and develop income-generating activities to reimburse at least parts of their operating costs (Goerke 2003). However, the earned income is still insufficient to cover all the operating costs and sustain continuous operations (Goerke 2003). On the contrary, social ventures are economically sustainable (Dees 1998; Santos 2012). Although social ventures can still be partially funded by external donations or public funds, they rely on their own earned income to sustain operations or support expansion, either domestically or internationally.

Social ventures and nonprofit organizations share similarities, despite their core difference on economic sustainability. Both social ventures (Zahra et al. 2014) and nonprofit organizations (Gonzalez et al. 2002) are socially oriented organizations that are motivated to create social benefits contributing to the overall well-being of the society or community (Kroeger and Weber 2015). Social entrepreneurial activities can exist in a wide range of organizations (Zahra et al. 2009), including both social ventures (Zahra et al. 2014) and nonprofit organizations (Alvarez et al. 2015). Both social ventures and nonprofit organizations with profit-generating activities create blends of economic and social values. At the same time, both social ventures (Zahra et al. 2014) and nonprofit organizations (Alvarez et al. 2015) can expand their operations internationally or even globally and alleviate social pains beyond their home country. The current business and management literature has, however, not yet compared social ventures and nonprofit organizations in terms of internationalization.

Nonprofit organizations are driven by inflow of external funding, especially inflow of public funds (Kearns 1996; Bryson 2011). The public sector that manages the public funds, such as national or regional government institutions, in most cases only has intentions or interests to invest in nonprofit organizations that aim to create social benefits within the national (or regional) border, and not those with interests beyond the national (or regional) border (Kearns 1996). Nonprofit organizations’ reliance on external public funds would limit their potential to geographically expand their operations, especially beyond the national border. On the contrary, social ventures rely on their own earned income to sustain operations and expand. Decision making regarding international expansion in social ventures is subject to lesser influence by the public sector. We therefore hypothesize that:

H1:

Social ventures are more likely to internationalize than nonprofit organizations.

Social Interventions and Internationalization

The ultimate goal of SE, no matter the form of socially oriented organization involved, is to create social value, which contributes to the well-being of disadvantaged individuals (Martin and Osberg 2007) and the overall well-being of the society (Zahra et al. 2009, 2014). Disadvantaged individuals are often referred to as beneficiaries in the social context (Bruce 1995; Gonzalez et al. 2002). However, similar to the other types of value, social value is intangible (Di Domenico et al. 2010). Scholars usually measure or categorize the output of value that is created in an organization. For example, the output of economic value for the entrepreneur, which is created in a venture, is the profit that the entrepreneur can withdraw from the venture. The output of social value is referred to as social interventions that focus on the eventual changes in well-being of the beneficiary group (Kroeger and Weber 2015). For example, a microfinance institute in Bangladesh helped women at the bottom of the pyramid by providing microfinance and investment lessons to help them break the vicious cycle of poverty. In this case, the microfinance institute conducted microfinance interventions that improved the financial situation and investment skills of the beneficiary group (women at the bottom of the pyramid in Bangladesh), by providing the beneficiary group micro-credits and investment lessons (Yunus 2007; examples given in Kroeger and Weber 2015).

Social interventions are not as homogeneous as economic profit, which can be easily measured by monetary unit (Di Domenico et al. 2010). The realization of social value of different nature creates different types of social interventions (Kroeger and Weber 2015). Social interventions are heterogeneous (Cummins 1996) and highly context dependent (Zahra et al. 2008). Social interventions can have different beneficiary groups, even within the same community. Similar beneficiary groups in different institutional and cultural contexts can have different social demands. Social demands in one community (e.g. women’s limited access to gym and other sport facilities in an Islamic community) could become nonexistent in another community within a different context (e.g. a Northern European community). It is thus challenging to categorize and measure different and unrelated interventions that serve different beneficiary groups in different institutional and cultural contexts (Austin et al. 2006; Dacin et al. 2010; Mair and Marti 2006; Zahra et al. 2009; Kroeger and Weber 2015).

In addition, scholars of SE and nonprofit management (Diener et al. 2013; Kroeger and Weber 2015) or practitioners (e.g. Office for National Statistics 2015) widely accept that the overall well-being of a community (or a society) is a function of satisfactions in multiple fictive life domains. One of the most well-known models has a design of satisfactions in seven life domains (Cummins 1996), specifically education, financial situation, health, housing, community integration, equality and safety (see Table 9.1). A socially oriented organization can conduct social interventions to improve satisfaction in one or multiple life domains. This idea of life satisfaction in multiple domains is now widely adopted by practitioners. For example, the Measuring National Well-being Project by the Office of National Statistics (2015) measures life satisfaction in ten life domains. Though not exactly similar, these ten life domains largely overlap with the seven life domains of Cummins’ original model (1996). Since Cummins’ theoretical model was introduced almost two decades ago, it might not perfectly fit into the present socio-economic context. Practitioners, such as the Office of National Statistics (UK), drew on academic research in the field of SE and sustainability to extend the range of life domains. For example, the development of knowledge on environmental sustainability (Shepherd and Patzelt 2011) significantly led to the inclusion of satisfaction with the natural and communal environment. Satisfaction in the health domain was extended to both physical health and mental health. Satisfaction in the education domain was extended to both formal education and work-related informal education (see Table 9.1).

Most of the existing life satisfaction theories from either academics or practitioners were developed in the context of developed economies. These existing models may be unsuitable for a developing economy context, as they largely omit some social pains that widely exist in developing economies but are less common or almost nonexistent in developed economies, such as hunger and malnutrition and gender equality in patriarchal societies (see, for example, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations 2014). Social interventions that alleviate those social pains can significantly increase the well-being of beneficiary groups in some developing economies. In sum, existing theories of multiple-domain life satisfaction do not share a uniform understanding of how to divide life domains, which can be further used to categorize social interventions. In addition, these theories might not fit the context of developing economies. As a result, based on a data set covering 271 socially oriented organizations in 63 counties, we employ exploratory methods to define our own categories of life domains and use them to categorize types of social interventions.

Socially oriented organizations differ according to the type of social interventions they undertake, which then affects their likelihood of internationalization, as different types of social interventions tend to have different resource requirements. The delivery of some social interventions relies heavily on financial resources or knowledge-intensive intangible resources or tacit knowledge of the local socio-economic context and networks (Zahra et al. 2009). When a social entrepreneur tries to copy successful experience from one location to another unknown location, mobilizing and transferring financial or knowledge-based resources to the new location tends to be less challenging than obtaining relevant tacit knowledge and localized human resources. For example, undertaking social interventions in the health domain (in Table 9.1) to eradicate an epidemic in a developing economy may heavily rely on knowledge-intensive resources (e.g. low-cost medicine or medical treatment) that can only be found in a developed economy. A socially oriented organization that conducts this kind of social intervention in a developing economy is highly likely to have border-crossing activities, given the need to leverage knowledge-intensive resources located in a developed economy to meet identified needs in a developing economy. On the contrary, undertaking social interventions in the safety domain (in Table 9.1), to make females feel safer to walk alone after dark in a British community, would require deep understanding of the social, economic, demographic and historical reasons behind this type of crime, in addition to relationship building with the local police, other public actors, residents in the community or even potential female attackers. A socially oriented organization that conducts social interventions to make females feel safer to walk alone after dark is more likely to stay within that community than expand internationally, since the organization cannot easily mobilize and transfer the required resources (such as localized human resources and embeddedness in the local networks) from one community (or society) to another. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2:

Socially oriented organizations that conduct different types of social interventions differ on the likelihood of internationalization.

Institutional Strength in the Home Country and Internationalization

Institutions refer to authoritative guidelines and constraints for individual behaviours, which are deeply embedded in the social structure (North 1990; Scott 2005). Institutional environments have strong impacts on cross-border entrepreneurship activities by shaping the entrepreneur’s cognition (Zahra et al. 2005). Strong institutions are characterized by good enforcement of commercial and intellectual property laws, transparent judicial and litigation systems, developed factor markets and efficient market intermediates (Peng 2003). Better-developed institutional environments in the home country are found to support the internationalization of firms (Wu and Chen 2014), since strong institutions can provide more tangible and intangible resource support (Buckley et al. 2007; Stephan et al. 2015). By contrast, unstable and frequently changing institutional environments of the home country cannot provide sufficient institutional support for the internationalization of socially oriented organization and sometimes even prohibit internationalization (Wu and Chen 2014). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3:

Socially oriented organizations from economies with stronger institutions are more likely to internationalize.

Methods

Data

The data used in this study were adopted from the Social Entrepreneur Database by the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship. The Social Entrepreneur Database by the Schwab Foundation included a diverse range of real-life social entrepreneurs who created socially oriented organizations tackling different forms of social issues in countries with different development levels. The Database included 271 real-life socially oriented organizations from 63 countries (listed in Table 9.2) and provided us with an overview of the spectrum of SE activities, which was often overlooked in country-specific case studies. The Database provided detailed descriptions of the social issues tackled by each socially oriented organization, and the socially significant products, services or solutions that the organization provides. The Database also outlined the educational and experiential background of the entrepreneur for each case.

The Database and other supplementary textual documents were first coded into quantitative data used in a sequential statistical analysis in early 2015. The quantitative data reflected each socially oriented organization’s status (e.g. cross-border activities, social interventions undertaken etc.) by the end of the year 2014.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable “Internationalization” measured whether the socially oriented organization had activities beyond its national border or not. If a socially oriented organization had activities beyond its national border, it was considered to be “international”; if a socially oriented organization did not have activities beyond its national border, it was considered to be “domestic”. The dependent variable “Internationalization” was a binary variable with the value of 1 if the socially oriented organization was international and the value of 0 if the socially oriented organization was domestic.

Independent Variables

Organizational Form: Social Ventures Versus Nonprofit Organizations

Social entrepreneurial activities can exist in a wide range of organizations (Zahra et al. 2009), from profit-oriented ventures with social value created as a byproduct, to socially oriented organizations with active social value creation, such as social ventures and nonprofit organizations. The Social Entrepreneur Database by the Schwab Foundation only included socially oriented organizations. Consistent with the literature (Yunus 2007; Santos 2012), the Database used organizations’ economical sustainability (i.e. whether the organization’s earned income can cover its operating costs or not) as the standard to differentiate social ventures from nonprofit organizations with income-generating activities. A binary independent variable “Organizational form” was created to differentiate whether a socially oriented organization was a social venture or a nonprofit organization, with the value of 1 if the socially oriented organization was a social venture and the value of 0 if the socially oriented organization was a nonprofit organization.

Types of Social Interventions

An exploratory method was used to figure out the possible types of social interventions that can be conducted by socially oriented organizations, since existing typologies do not fit the present global business environment, nor the context of developing economies. We collected textual descriptions of each socially oriented organization’s targeted social issues and business models from the Social Entrepreneur Database and the official websites of the focal socially oriented organizations (terms such as vision, mission and activities were looked for) and used these as empirical data. Keywords, describing social issues of concern or socially significant products, services and innovations introduced, as well as who the beneficiaries were and how they benefited, were extracted from the empirical data (see the Appendix for examples of keywords). We focused on the eventual improvements of the well-being of beneficiaries that had been served by socially oriented organizations instead of these organizations’ long-term social goals. One or multiple keywords could be extracted from each socially oriented organization, and these were then grouped into categories by their inherent similarity (Gioia et al. 1994, 2013), regardless the source of extraction. As a result, eight types of social interventions were found to be conducted by socially oriented organizations from the empirical data (Table 9.3). These were named as Codes #1.

Sequentially, we coded the empirical data for all the 271 socially oriented organizations, not by extracting keywords, but by assigning one or multiple standardized types of social interventions (as in Table 9.3) for each socially oriented organization. The coding process was conducted twice, following different alphabetic orders. The codes obtained from the sequential two coding processes were named Codes #2 and Codes #3, respectively.

Codes #1, #2 and #3 were further compared. Codes #1 and #2 shared a similarity of 87 percent. Codes #2 and #3 shared a similarity of 97 percent. Codes which were found to differ across Codes #1, #2 and #3 were selected and further validated by rechecking the empirical data and, if necessary, collecting additional textual data, such as corporate webpages and media exposures. One of the major sources for the differences among Codes #1, #2 and #3 was that we did not clearly differentiate between social interventions which had been conducted and long-term social missions which were targets to achieve in the future when we obtained Codes #1. The final codes were generated after validation, used in the sequential analyses and labeled as Codes #4. Codes #4 shared similarities of 83 percent, 98 percent and 97 percent with Codes #1, #2 and #3, respectively.

Eight binary independent variables “DIS”, “EMP”, “EDU”, “ENV”, “HEA”, “HMN”, “POV” and “RES” (Table 9.3) were generated to indicate whether a socially oriented organization conducted each of the eight types of social interventions or not, respectively. Each binary variable has the value of 1 when the socially oriented organization has conducted this type of social intervention and the value of 0 when it has not.

Institutional Strength in the Home Country

We measured institutional strength in the home country from the perspectives of economic development, social development and institutional development (governance) and merged a variety of data sets with multiple national-level measures. The measure for economic development was the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita adjusted in US dollars in 2014, collected from the World Bank database. The measure for social development was the Human Development Index (HDI) in 2014, collected from the United Nations Development Programme database. HDI measures the average achievements in a national economy on three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. The level of governance or institutional development was measured using the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) developed by the World Bank Group. Three relevant dimensions out of the total six WGI dimensions were selected and the scores on the year 2014 were used. The three measures were government effectiveness (GE), regulatory quality (RQ) and the rule of law (RL). GE measures the quality of public services, civil services and policy formulation and implementation. RQ measures the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies to permit and promote private sector development. RL measures the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. In sum, we use five continuous variables, “GNI”, “HDI”, “GE (WGI)”, “RQ (WGI)” and “RL (WGI)” to measure institutional strength in the home country.

Control Variables

The gender of the entrepreneur and the organization’s age are commonly used demographic control variables in a cross-country study of entrepreneurship (Lloyd-Reason and Mughan 2002; Van Stel et al. 2007; Estrin et al. 2013). A binary control variable, “Gender of entrepreneur”, was created, with the value of 1 when the entrepreneur(s) are all male entrepreneurs and the value of 0 when the entrepreneur is female, or at least one of the entrepreneurs is female. A continuous control variable, “Organization age”, was created to measure the number of calendar years from the establishment of the socially oriented organization till the end of the year 2014. For example, a socially oriented organization established in the year 2013 has an organization age of 2 years on the data set.

Models

A binary logistic regression model was ideal for this study, since the dependent variable is binary and it was intended to test the effects of two control variables in the same model. The dependent variable “Internationalization” was binary with the value of 1 if the socially oriented organization is international and 0 if the socially oriented organization is domestic. The independent variable “Organizational form” was binary with the value of 1 if the socially oriented organization is a social venture and 0 if the socially oriented organization is a nonprofit organization. Eight independent variables “DIS”, “EMP”, “EDU”, “ENV”, “HEA”, “HMN”, “POV” and “RES” were binary, with each representing whether the socially oriented organization conducted each of the eight types of social interventions or not, respectively. Five continuous variables, “GNI”, “HDI”, “GE (WGI)”, “RQ (WGI)” and “RL (WGI)”, were selected to measure the institutional strength in the home country from the perspectives of economic, social and institutional development. The binary variable “Gender of entrepreneur” and continuous variable “Organization age” were selected as control variables. Descriptive statistics of variables on the binary logistic regression model are summarized in Table 9.4.

Results

Institutional Strength in the Home Country

The five national-level measures strongly correlate with each other (Pearson correlation coefficients range from 0.797 to 0.957, as in Table 9.5), thus implying problems with multicollinearity. A principal component score of the five national-level measures was then used instead of the five national-level measures. A single component emerged from the principal component analysis of the five national-level measures, with an eigenvalue of 4.44, explaining 88.9 percent of the variance. The component loadings were all in excess of 0.910.

Results of Binary Logistic Regression

The results of the binary logistic regression are reported in Table 9.6. The model’s chi-square significance was smaller than 0.001, showing that the model was a significant fit of the data. The gender of the entrepreneur and the age of socially oriented organization were not critical in predicting the likelihood of internationalization of a socially oriented organization.

We found that social ventures did not differ significantly from nonprofit organizations in terms of the likelihood of internationalization. H1 was therefore refuted. We found that socially oriented organizations conducting EMP-type social interventions were less likely to be international than those not conducting EMP-type social interventions. We also found that socially oriented organizations conducting EDU-, ENV-, HEA- and RES-type social interventions were more likely to internationalize than those not conducting EDU-, ENV-, HEA- and RES-type social interventions, respectively. H2 was supported. We found that socially oriented organizations from economies with stronger institutions were more likely to internationalize. H3 was also supported.

Discussion

The Organizational Form of a Socially Oriented Organization Is Not Critical in Predicting Its Likelihood of Internationalization

We found that social ventures did not differ significantly from nonprofit organizations in terms of the likelihood of internationalization. This suggests that whether a socially oriented organization is economically sustainable (or not) is not critical on its decision to internationalize or not. Socially oriented organization’s internationalization decision might depend more on other factors, for example, where the targeted beneficiaries are located and whether the resources required to undertake social interventions to improve the well-being of the targeted beneficiaries are located within the same national border. If some of the required resources are located in a different country from that of the targeted beneficiaries, the delivery of social interventions would inevitably involve cross-border resource combination. Socially oriented organizations internationalize when conducting social interventions that require cross-border resource combination. However, this finding cannot be fully verified in this study and needs to be tested in future research.

Although social ventures and nonprofit organizations do not differ significantly on the likelihood of internationalization, international social ventures and international nonprofit organizations might still differ on market choice. Social ventures are expected to have similar international market selection strategies as profit-oriented ventures, since the total amount of resources for economically sustainable social ventures is limited. By contrast, nonprofit organizations can leverage the advantages of external funding inflow and choose to expand into international markets with deeper social pains. Those international markets might be less attractive to social ventures since operations in those markets are less likely to be delivered in an economically sustainable manner due to pervasive institutional failure and weak institutional support. The market choice of international social ventures and that of international nonprofit organizations still need to be further evaluated in future research.

Types of Social Interventions Conducted by Socially Oriented Organization and Likelihood of Internationalization

We found that socially oriented organizations that conducted EMP-type social interventions were less likely to internationalize than those which did not. The reason could be that conducting social interventions that improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with employment opportunities and employment condition relies heavily on the social entrepreneur’s knowledge of the local socio-economic context and embeddedness in the local networks (Zahra et al. 2009). Socially oriented organizations that successfully conducted EMP-type social interventions found it difficult to rapidly copy their successful experience from one community (or country) to another community (or country). The reason could be that it is time consuming and costly to gather the required tacit knowledge and localized human resources in the new community (or country).

We also found that socially oriented organizations that conducted EDU-, ENV-, HEA- or RES-type social interventions were more likely to internationalize than those which did not. The reason could be that socially oriented organizations could leverage the advantages of knowledge-intensive intangible resources or capabilities and innovation (Cavusgil and Knight 2015) to improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with formal and informal education, natural and communal environment, physical and mental health, and access to physical resources such as clean water, energy and housing. For example, socially oriented organizations can introduce low-cost and technologically innovative intraocular lens and cataract surgeries to cure blind people in poor communities; they can also introduce low-cost and technologically innovative UV-light devices to clean contaminated water in natural water resources to provide people in poor communities with access to clean and safe water sources and eradicate water-borne epidemics. In addition to technological innovation, socially oriented organizations can leverage the advantages of socially significant and innovative services or solutions to improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with education, environment, health and access to physical resources. For example, socially oriented organizations can introduce innovative education methods to help children who are away from, or cannot survive, in the national formal education system. In sum, socially oriented organizations that conduct EDU-, ENV-, HEA- or RES-type social interventions can leverage the advantages of knowledge-intensive resources and technological or social innovation to achieve internationalization.

Lastly, we found that socially oriented organizations which conducted DIS-, HMN- or POV-type social interventions did not differ in terms of the likelihood of internationalization from those which did not. In most cases, conducting social interventions that help disadvantaged beneficiary groups, improve community integration and harmony, or eradicate poverty heavily relied on the social entrepreneur’s knowledge of the local socio-economic context and embeddedness in the local networks (Zahra et al. 2009), similar to conducting EMP-type social interventions. For example, socially oriented organizations that conduct social interventions to reduce the reliance of local businesses on the mafia and increase community harmony in Southern Italy required deep understanding of social, cultural, economic and historical backgrounds of the Mafia and Mafia-influenced community and trust-building with the local business owners to help them fight against the fear of the Mafia. The successful experience of those socially oriented organizations cannot easily be copied beyond the Mafia-influenced communities in Southern Italy. However, at the same time, socially oriented organizations that conduct social interventions to help disadvantaged beneficiary groups, improve community integration and harmony or eradicate poverty can destroy the dated social systems and introduce revolutionary changes, by instigating new and more suitable social systems (see examples of Social Engineers in Zahra et al. 2009), and that experience can be used beyond national borders. For example, microfinance institutes can conduct microfinance interventions to break the vicious cycle of poverty by changing the social structure and copying successful experience nationwide or beyond the national border, internationally or even globally. Socially oriented organizations which conduct DIS-, HMN- or POV-type social interventions have a diverse range of impact, from community-based to global.

Home Country Institutions of Socially Oriented Organization and Likelihood of Internationalization

The institutional contexts of both the home country and the host country are long known to have a strong impact on the internationalization of profit-oriented ventures (Buckley et al. 2007; Wu and Chen 2014). We discovered that stronger and better-developed institutions in the home country provided better institutional support not only to the internationalization of profit-oriented ventures, but also to socially oriented organizations. That said, the impact of the institutional environment in the home country on the internationalization of socially oriented organizations and profit-oriented ventures still needs to be further investigated in the future.

Conclusion

Based on a data set covering 271 socially oriented organizations from 63 countries with rich textual details, we explored the impact of three potential determinants of the internationalization of socially oriented organizations. The three potential determinants are (1) the organizational form, whether the socially oriented organization is economically sustainable or not; (2) the social nature, which types of social interventions the socially oriented organization undertakes and (3) the strength of the institutional environment in the home country.

Our findings are as follows. The organizational form of a socially oriented organization (i.e. a social venture or a nonprofit organization) is not critical in determining its likelihood of internationalization. The conduct of social interventions to improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with employment opportunities and employment condition by a socially oriented organization reduces its likelihood of internationalization. The conduct of social interventions to improve beneficiaries’ satisfaction with formal and informal education, natural and communal environment, physical and mental health, and access to physical resources such as clean water, energy and housing by a socially oriented organization increases its likelihood of internationalization. Stronger and better-developed institutions in the home country can provide better institutional support for the internationalization of socially oriented organizations.

The findings help reveal the nature of the internationalization of socially oriented organizations. Socially oriented organizations internationalize when conducting social interventions whose delivery requires cross-border resource combination. In most cases, the requirement for cross-border resource combination arises because the targeted beneficiaries and at least some of the necessary resources for social interventions were not located in the same country. The findings also have implications for policy makers and public money managers. Socially oriented organizations differ in their capability for international expansion: some only stay in a local community, while others can diversify operations and have an impact at the global level. Socially oriented organizations of different organizational forms and social nature require different resources (both tangible and intangible) and support from public institutions for their continuing operations and expansion.

References

Ahlstrom, D. (2010). Innovation and growth: How business contributes to society. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 11–24.

Alexander, J. A., & Weiner, B. J. (1998). The adoption of the corporate governance model by nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 8(3), 223–242.

Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Newman, A. M. B. (2015). The poverty problem and the industrialization solution. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 23–37.

Andreasen, A. R., & Kotler, P. T. (2003). Strategic marketing for non-profit organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Audretsch, D. B. (2015). Everything in its place: Entrepreneurship and the strategic management of cities, regions, and states. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Boli, J., & Thomas, G. M. (1997). World culture in the world polity: A century of international non-governmental organization. American Sociological Review, 62(2), 171–190.

Bruce, I. (1995). Do not-for-profits value their customers and their needs? International Marketing Review, 12(4), 77–84.

Bryson, J. M. (2011). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Buckley, P. J., Jeremy Clegg, L., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 499–518.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Knight, G. (2015). The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1), 3–16.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38(3), 303–328.

Dacin, P. A., Dacin, M. T., & Matear, M. (2010). Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 37–57.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits. Harvard Business Review, 76(1), 55–66.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Di Domenico, M.-L., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681–703.

Emerson, J. (2003). The blended value proposition: Integrating social and financial returns. California Management Review, 45(4), 35–51.

Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Stephan, U. (2013). Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 479–504.

Ghauri, P., Tasavori, M., & Zaefarian, R. (2014). Internationalisation of service firms through corporate social entrepreneurship and networking. International Marketing Review, 31(6), 576–600.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

Gioia, D. A., Thomas, J. B., Clark, S. M., & Chittipeddi, K. (1994). Symbolism and strategic change in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organization Science, 5(3), 363–383.

Goerke, J. (2003). Taking the quantum leap: Nonprofits are now in business. An Australian perspective. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8(4), 317–327.

Gonzalez, L. I. A., Vijande, M. L. S., & Casielles, R. V. (2002). The market orientation concept in the private nonprofit organisation domain. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7(1), 55–67.

Kearns, K. P. (1996). Managing for accountability: Preserving the public trust in public and nonprofit organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Kroeger, A., & Weber, C. (2015). Developing a conceptual framework for comparing social value creation. Academy of Management Review, 40(1), 43–70.

Lloyd-Reason, L., & Mughan, T. (2002). Strategies for internationalisation within SMEs: The key role of the owner-manager. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9(2), 120–129.

London, T., & Hart, S. L. (2004). Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 350–370.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44.

Martin, R. L., & Osberg, S. (2007). Social entrepreneurship: The case for definition. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 5(2), 28–39.

Norman, W., & MacDonald, C. (2004). Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line”. Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(2), 243–262.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Office for National Statistics. (2015). National well-being measures, September 2015. London: Office for National Statistics.

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(4), 631–652.

Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275–296.

Rondinelli, D. A., & London, T. (2003). How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Academy of Management Executive, 17(1), 61–76.

Roy, A., & Goll, I. (2014). Predictors of various facets of sustainability of nations: The role of cultural and economic factors. International Business Review, 23(5), 849–861.

Santos, F. M. (2012). A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 335–351.

Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. In K. G. Smith & M. A. Hitt (Eds.), Great minds in management: The process of theory development (pp. 460–484). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2011). The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 137–163.

Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L. M., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(3), 308–331.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2006). Making globalization work. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2010). Freefall: America, free markets and the sinking of the world economy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Teegen, H., Doh, J. P., & Vachani, S. (2004). The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: An international business research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(6), 463–483.

United Nations. (2014). Open working group proposal for sustainable development goals. New York: United Nations.

Van Stel, A., Storey, D. J., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 171–186.

World Bank. (2012). World Bank sees progress against extreme poverty, but flags vulnerabilities. Washington, DC: World Bank Press Release, February 29, 2012.

Wu, J., & Chen, X. (2014). Home country institutional environments and foreign expansion of emerging market firms. International Business Review, 23(5), 862–872.

Yunus, M. (2007). Creating a world without poverty: Social business and the future of capitalism. New York: Public Affairs.

Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O., & Shulman, J. M. (2009). A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519–532.

Zahra, S. A., Korri, J. S., & Yu, J. (2005). Cognition and international entrepreneurship: Implications for research on international opportunity recognition and exploitation. International Business Review, 14(2), 129–146.

Zahra, S. A., Newey, L. R., & Li, Y. (2014). On the frontiers: The implications of social entrepreneurship for international entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 137–158.

Zahra, S. A., Rawhouser, H. N., Bhawe, N., Neubaum, D. O., & Hayton, J. C. (2008). Globalization of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 117–131.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Examples of Keywords Extracted Corresponding to the Eight Types of Social Interventions

Appendix: Examples of Keywords Extracted Corresponding to the Eight Types of Social Interventions

Codes | Examples of keywords |

|---|---|

DIS | disadvantaged, vulnerable, marginalized, neglected group, grassroots, (people) excluded from society, to obtain status in society, (people with) physical/mental disabilities, physical disabled/handicapped/blind/visually impaired/deaf/hearing impaired (people), women and children (after decades of wars/long-term absence of male family members/etc.), rural women/youth, refugees, slum dwellers, migrants labourers |

EMP | Keywords linked with employment opportunities: employment/job opportunities, job placements, jobless, unemployed, excluded from opportunities, devoid of opportunities Keywords linked with employment conditions: labour conditions, employment conditions, protection from malpractices/hazards |

EDU | Keywords linked with formal education: (unable to) read and write, (il)literacy, access to education, (high) dropout rate, (low) enrollment rate, education/enrollment of girls, improve school enrollment/retention/(public) school performance/outcomes/passing rates, (lack of) school facilities, access to books/libraries, access to student loans, teaching methodology, (to improve) reading/writing/mathematics capabilities, (to promote) problem solving/critical thinking, alternative path (for high school/college education) Keywords linked with informal education: professional training, vocational training, skills training, market-relevant skills, capacity building, agricultural education, to build/develop (self-)confidence |

ENV | (environmentally/ecologically) sustainable, sustainability, ecotourism, conservation, to safeguard rainforest, to combat the trafficking of wildlife, to conserve species/ecosystems, biodiversity, to reverse depleted fish stocks/sustainable fishing, climate change, low carbon communities, to reduce energy use/emissions, low environmental impact, (ecologically) sustainable farming/agriculture, (to reduce) use of inorganic fertilizers/pesticides/herbicides, micro-irrigation technology (to save water use), pollution monitoring, consumer awareness/conscious consumption, urban/communal environmental issues, green spaces, recycling, waste management, hazardous waste, bio-degradable plastics |

HEA | Keywords linked with physical health: healthcare, to improve healthcare access, health services, health needs, health risks (associated with…), post-care support, (high) infant mortality rate, low-cost infant warmer, sanitary conditions, public health, epidemics, (to eradicate) cholera/typhoid/malaria/tuberculosis, HIV treatment/care support, (low-cost) cataract surgery/intraocular lenses/ophthalmic products, blood cancer, malnutrition, chronic hunger, (affordable/specialized) diabetes care, low-price food, food scarcity, food security Keywords linked with mental health: mental/psychological health/illnesses/diseases, anxiety, depression |

HMN | (gender/race/income/social class (caste)) (in)equality, empowerment of women, women’s leadership, human rights, (post-communism) political transformation, civic engagement, to build a democratic state, social change, crime prevention, crime victims, Mafia extortion, (to prevent) domestic violence/abuse, to promote cultural integrity, restoration and enhancement of heritage sites, handicraft/craft production, community/society harmony, social integration, social inclusion, community participation/collaboration, neighborhood transformation |

POV | poverty, to eradicate poverty, to remove the structural causes of poverty, impoverished region, income generating, wealth creation, economic development, regional/rural development, limited financial resources/funding, microfinance, microcredit, micro-loans, micro-leasing arrangements |

RES | safe/unsafe/clean (drinking) water, (water) purification, (affordable) water filters, solar energy/lighting/lantern/mobile phone charger, biomass-based electricity, inexpensive fuel (biogas), mini power stations (fueled by weeds and agricultural wastes), micro-hydro plants, cost-effective electricity distribution system, (affordable/cost-effective) housing, homelessness, post-earthquake reconstruction, (to recycle and distribute) clothing/bicycles/under-utilized resources (from urban households to the rural poor, or from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa), to develop distribution network (of consumer goods to reach rural villages) |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chen, J., Saarenketo, S., Puumalainen, K. (2017). The Internationalization of Socially Oriented Organizations. In: Ibeh, K., Tolentino, P., Janne, O., Liu, X. (eds) Growth Frontiers in International Business. The Academy of International Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48851-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48851-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-48850-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-48851-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)