Abstract

A popular view in economics, supported by numerous claims, is that artists are poor and unsuccessful and, thus, must be unhappy. Artists such as Franz Kafka, Emily Dickinson, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, or Franz Schubert, all of whom were unsuccessful artists during their lifetime and, in some cases, mentally ill, have received considerable attention in the public, art history, and philosophy. The persistent popularity around the link between creativity and mental illness may just be notionally rooted in society’s need to regard both genius and mental illness as “deviant.” However, the artistic labor market is indeed marked by several adversities, such as low wages, above-average unemployment, and constrained underemployment. Artists earn less, on average, than they would with the same qualifications in other professions, and their earnings display greater inequality than those of their reference group. They suffer from above-average unemployment and constrained underemployment, such as non-voluntary part-time or intermittent work. Nevertheless, the field of the Arts attracts many young people. The number of students by far exceeds the available jobs.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Artists do not fit into the standard economic model of labor supply, they work more, earn less, and are still happier than other workers. Time to focus on the process rather than the outcome.

A popular view in economics, supported by numerous claims, is that artists are poor and unsuccessful and, thus, must be unhappy. Artists such as Franz Kafka, Emily Dickinson, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, or Franz Schubert, all of whom were unsuccessful artists during their lifetime and, in some cases, mentally ill, have received considerable attention in the public, art history, and philosophy. The persistent popularity around the link between creativity and mental illness may just be notionally rooted in society’s need to regard both genius and mental illness as “deviant.” However, the artistic labor market is indeed marked by several adversities, such as low wages, above-average unemployment, and constrained underemployment. Artists earn less, on average, than they would with the same qualifications in other professions, and their earnings display greater inequality than those of their reference group. They suffer from above-average unemployment and constrained underemployment, such as non-voluntary part-time or intermittent work. Nevertheless, the field of the Arts attracts many young people. The number of students by far exceeds the available jobs.

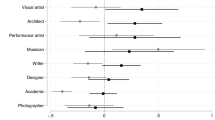

The classical economic explanation for this paradox is that artistic labor markets are superstar markets and artists are more risk loving. Another explanation from the realm of psychological economics states that artists overestimate the likelihood of future success. Both explanations are outcome oriented, focusing on the income artists derive as a result of their work. Jointly with coauthors, our research focused on a different approach, which emphasizes the importance of the process or the satisfaction artists experience during their work.

We found that artists are on average considerably more satisfied with their work than nonartists. The higher satisfaction is driven by superior “procedural” characteristics of artistic work, such as the variety of tasks, on-the-job learning, and opportunities to use a wide range of abilities and feel self-actualized at work. An idiosyncratic way of life, a strong sense of community, and a high level of personal autonomy, reflected by the higher self-employment rate among artists, contribute to the higher satisfaction. The relationship between income and job satisfaction is positive for artists and nonartists, as anticipated by classical economics. However, compared to nonartists the relationship is weaker for artists. This means that a higher income increases artists’ happiness, but less so than the happiness of nonartists. Interestingly, the assumption of the neoclassical models that working more hours makes individuals unhappy does not apply for artists. Working longer hours does not decrease their job satisfaction. As artists do not fit the standard economic model of labor supply, it would be wise to dismiss the notion of the poor and unhappy artist. Considering the satisfaction people can and do derive during their work or other activities, not only focusing on the outcomes individuals obtain, has the potential to further progress in economic research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Steiner, L. (2017). Artists Are Poor and thus Unhappy. In: Frey, B., Iselin, D. (eds) Economic Ideas You Should Forget. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_58

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_58

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47457-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47458-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)