Abstract

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a progressive clinical syndrome that includes gait disturbances, urinary incontinence, and cognitive impairment. iNPH shows similarities to other neurodegenerative disorders, primarily Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Definition of the neuropsychological profile of iNPH and the qualitative analysis of systematic mistakes made in cognitive tests could represent a valid method for systematizing possible specific markers of iNPH dementia and differentiating it from other dementias. To evaluate the role and the efficacy of a neuropsychological protocol, designed at our institution, based on psychometric analysis and qualitative assessment, in the differential diagnosis of iNPH from AD dementia, we prospectively enrolled 12 patients with suspected iNPH, 11 patients with AD, and 10 healthy controls (HC) who underwent neuropsychological assessment. The assessment was done with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Mental Deterioration Battery (MDB), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), and the Deux Barrage Test. Evaluation in the iNPH group was performed before extended lumbar drainage (ELD), 48 h after ELD, and 1 week and 3 months after the insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS). Statistical analysis demonstrated the cognitive profile of iNPH, which was mainly characterized by executive function and immediate verbal memory impairment compared with AD. Additionally, the neuropsychological markers were different between the two groups. The qualitative analysis of systematic mistakes made on the tests demonstrated differences in cognitive performances between the iNPH, AD, and HC cohorts. Neuropsychological assessment and qualitative evaluation could represent a useful tool for achieving effective management and restoration of functions in patients with iNPH.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus

- Neuropsychological assessment

- Qualitative analysis

- Restoration

Introduction

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) accounts for 2 %–10 % of all forms of dementia and 40 % of adult hydrocephalus [9]. The correct identification of iNPH, frequently hidden in the setting of coexisting diseases, and considering that 1 % of the population aged ≥65 years old shows ventriculomegaly without symptoms [10], is critical for maintaining neuronal and neuropsychological integrity and restoration [12]. However, the criteria used to select patients for treatment remain unclear [1]. The large amount of data that has emerged from recent series suggest that the cognitive profile of iNPH is a complex result of the impairment of several areas, which leads to specific alterations in executive functions, working memory, speed processing information, attention, learning and memory, and visuospatial functions, similar to the cognitive profile in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) [8, 9]. The modern concept of iNPH cognitive disorders is of a dysexecutive syndrome with episodic and immediate memory dysfunction [3, 5]. There is a lack of specific diagnostic criteria needed to systematically define neuropsychological markers that would be useful for achieving early diagnosis and outlining the specific neuropsychological profile of iNPH. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role and the efficacy of a neuropsychological protocol, designed at our institution, based on psychometric analysis and qualitative assessment, in the differential diagnosis of iNPH from AD dementia.

Materials and Methods

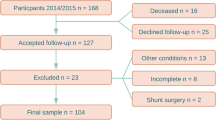

The Institutional Ethics Board of the University of Messina approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from each patient and/or their relatives. We prospectively enrolled 12 patients with clinically and neuroradiologically suspected iNPH. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥65 years, clinical triad (gait disturbances, dementia, and urinary incontinence), ventriculomegaly on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and other neuroradiological characteristics. Patients underwent a neuropsychological evaluation, with qualitative analysis to assess any systematic mistakes. Results were compared with those for 11 AD patients and 10 healthy controls (HC). The neuropsychological assessment was performed by C.S. and M.Q. (clinical neuropsychologists) on admission, 48 h after extended lumbar drainage (ELD) positioning, and postoperatively (1 week, and 1 and 3 months after VPS), when applicable. Patients who responded positively to preoperative tests for iNPH diagnosis were submitted to ventriculoperitoneal shunting with a programmable valve (Codman Hakim Medos; Codman & Shurtleff, Inc., 325 Paramount Drive, Raynham, MA 02767 0350, USA).

Neuropsychological Assessment

Quantitative Analysis

The neuropsychological protocol adopted was chosen for its wide use in the neuropsychological community to assess dementia disorders, as it included several batteries for the assessment of general cognitive status, short- and long-term memory, episodic memory, immediate visual memory, constructive praxia, reasoning, and executive functions. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), consisting of 30 items, allowed the exploration of temporospatial orientation, memory, attention, calculation, language (comprehension, repetition, denomination, reading, and writing), and constructive praxia. The highest score of 30 was modified in relation to age and education. The Mental Deterioration Battery (MDB) was divided into verbal and nonverbal tasks, including neuropsychological tests to detect the deterioration of different cognitive areas: memory, intellectual function, language, executive functions, and constructive praxia. The MDB included seven subtests for immediate and delayed recall, the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), for evaluating semantic and phonological fluency, phrase construction, and immediate visual memory; and Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices test (PM 47), which involves copy drawings, and copy drawings with landmarks. The Deux Barrage Test was used to evaluate divided attention. The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) enabled the assessment of executive functions.

Qualitative Analysis

In order to distinguish between cognitive impairments in iNPH and AD, we employed the following markers for AD diagnosis: in RAVLT, the absence of the primacy effect derived from a verbal learning task, the presence of the recency effect, the absolute decay of memory trace, and the tendency to produce false alarms during delayed recognition of the same word list; in Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices test, the tendency to choose globalistic or odd responses and positional preference mistakes; in the copy drawings test, the occurrence of the closing-in phenomenon; and in the Deux Barrage Test, inaccuracy in task execution. When the abovementioned markers were mostly presented, we were able to confirm the AD diagnosis, and to exclude those clinically suspected of having iNPH.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA 92037, USA). For the descriptive analysis of neuropsychological scores we used nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA); we used the Fisher test to compare the frequencies of systematic mistakes in iNPH and AD patients and the paired Student’s t-test to evaluate the effect of ventriculoperitoneal shunting on cognitive functions in iNPH patients. Additionally, we used the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) [23] to evaluate the covariance of cognitive functions in iNPH patients following surgical treatment. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We prospectively enrolled 12 patients (8 male; 4 female) with suspected iNPH; mean age 70 ± 6 years, mean educational level 9 ± 4 years. In order to compare psychometric results and systematic mistakes, we also enrolled 11 patients (7 male; 4 female) with AD; mean age 76 ± 5 years, mean educational level 8 ± 5 years; and 10 HC volunteers (4 male; 6 female), mean age 72 ± 8 years, mean educational level 11 ± 5 years. Seven iNPH patients who responded positively to preliminary tests, underwent ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunting within 2 weeks after assessment.

Quantitative Results

Table 1 summarizes the mean ± standard deviation values and statistics of the neuropsychological scores for the iNPH, AD, and HC groups on admission. As compared with the HC group, iNPH and AD patients showed significant impairments of different cognitive functions, including MMSE, short- and long-term memory (RAVLT), reasoning (PM 47), and semantic and verbal fluency, language, and constructive praxia. AD patients showed impairments of episodic memory, immediate visual memory, and executive functions. The ANOVA showed statistically significant differences between the iNPH and AD groups in MMSE, long-term memory, episodic memory, immediate visual memory, language, constructive praxia, and executive functions. Table 2 shows the frequencies of different mistakes in the iNPH and AD patients. The iNPH patients presented significant differences, compared with the AD group, in primacy effect, tendency to produce false alarms during delayed recognition of words, globalistic responses, odd responses, inaccuracy on the Deux Barrage Test, and the occurrence of the closing-in phenomenon. Table 3 shows the effect of VP shunting on cognitive performances. In detail, we observed a significant improvement in short- and long-term memory, immediate visual memory, and reasoning in these patients.

Correlational Analysis

When performing the correlational analysis of the neuropsychological scores, we did not find significant differences between the cognitive profiles of iNPH and AD patients. In the AD group the correlation coefficient showed a statistically significant between general cognitive dysfunction, memory, praxia, and executive function impairment (rho 0.814; p < 0.01). As compared with AD patients, the iNPH group showed a significant association between executive variables and memory abilities (rho 0.798; p < 0.05). In the iNPH group, we observed a significant cognitive improvement after ELD in immediate verbal memory and semantic phonological verbal fluency (rho 0.829; p < 0.05), and in divided attention and praxia (rho 0.926; p < 0.01). The improvement of immediate verbal memory, as assessed 1 week postoperatively, was significantly related to delayed verbal memory (rho 0.900; p < 0.05).

Discussion

In the present study we assessed the role of a neuropsychological protocol, combined with the qualitative analysis of systematic neuropsychological mistakes, in the differential diagnosis of iNPH from AD, as compared with results in the HC group. For this purpose we employed specific markers to exclude the AD syndrome, and we evaluated the frequencies of these markers in the iNPH patients. Moreover, the effect of surgery on postoperative cognitive neuropsychological restoration was evaluated. We have demonstrated that the psychometric tests cannot be considered as a sufficient tool for differentiating AD from iNPH patients. Conversely, the combination of neuropsychological markers and psychometric tests was able to achieve an effective differential diagnosis between iNPH and AD.

iNPH represents a complex syndrome for which several authors have attempted to systematize criteria, in order to obtain an effective differential diagnosis from other neurodegenerative disorders or comorbidities [7, 11, 16–19]. iNPH, and its neuropsychological profile, are, to date, still not clarified [6, 8, 14, 20], and a detailed characterization of the cognitive dysfunction in iNPH, especially in view of the specific neuropsychological patterns and differentiation of iNPH from AD, is crucial both for a correct diagnosis [4, 15, 21] and for obtaining neuropsychological restoration following treatment [2, 4, 22]. The neurocognitive profile of patients with suspected iNPH was mainly characterized by the impairment of executive functions and short-term memory [13], whereas in AD patients, the neurocognitive profile was mainly characterized by alterations of general cognitive status, short- and long-term memory, praxia, and executive functions. In detail, we found significant differences between the iNPH and AD groups in MMSE, long-term memory, episodic memory, immediate visual memory, language, constructive praxia, and executive functions. The qualitative analysis of systematic mistakes, made during the assessment, demonstrated statistically significant differences between our groups. iNPH differed from AD patients in the following markers: primacy effect, tendency to produce false alarms during delayed recognition of words, globalistic responses, odd responses, inaccuracy on the Deux Barrage, and the occurrence of the closing-in phenomenon. As compared with results in AD patients, scores in iNPH patients showed a significant association with executive variables and memory abilities. Changes in neuropsychological performances were demonstrated after ELD, 1 week after the operation, and at 1 and 3 months postoperatively.

The results of the present study are not unexpected, and are in line with those already published in the literature [6, 8]. We recognize that the limited series in the present study does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions. However, the neuropsychological assessment based on psychometric scores and qualitative analysis of neuropsychological patterns may represent a useful tool for making a correct differential diagnosis between iNPH and AD, and for achieving the restoration of neuronal and neuropsychological functions after treatment. These results may encourage an extension in the use of such a protocol to define the cognitive profile of iNPH.

References

Bergsneider M, Black MP, Klinge P, Marmarou A, Relkin N (2005) Surgical management of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:29–39

Campos Gomes Pinto F, Saad F, Fernades de Oliveira M, Pereira RM, Letsaske de Miranda F, Benevenuto Tornai J, Romao Lopes MI, Carvalhal Ribas ES, Valinetti E, Teixeira MJ (2013) Role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy and ventriculoperitoneal shunt in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: preliminary results of a randomized clinical trial. Neurosurgery 72:845–854

Devito EE, Pickard JD, Salmond CH, Iddon JL, Loveday C, Sahakian BJ (2005) The neuropsychology of normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). Br J Neurosurg 19(3):217–224

Gainotti G, Marra C, Villa G, Parlato V, Chiarotti F (1998) Sensitivity and specificity of some neuropsychological markers of Alzheimer dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 12(3):152–162

Golz L, Ruppert FH, Meir U, Lemcke J (2014) Outcome of modern shunt therapy in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus 6 years postoperatively. J Neurosurg 121(4):771–775

Hellstrom P, Edsbagge M, Archer T, Tisel M, Tullberg M, Wikkelso C (2007) The neuropsychology of patients with clinically diagnosed idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 61:1219–1228

Hellstrom P, Klinge P, Tans J, Wikkelso C (2012) A new scale for assessment of severity and outcome in iNPH. Acta Neurol Scand 126:229–237

Hellstrom P, Klinge P, Tans J, Wikkelso C (2012) The neuropsychology of iNPH: findings and evaluation of tests in the European multicentre study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 114:130–134

Iddon JL, Pickard JD, Cross JJ, Griffiths PD, Czosnyka M, Sahakian BJ (1999) Specific patterns of cognitive impairment in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 67:723–732

Iseki C, Kawanami T, Nagasawa H, Wada M, Koyama S, Kikuchi K, Arawaka S, Kurita K, Daimon M, Mori E, Kato T (2009) Asymptomatic ventriculomegaly with features of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus on MRI (AVIM) in the elderly: a prospective study in a Japanese population. J Neurol Sci 277(1–2):54–57

Ishikawa M, Hashimoto M, Kuwana N, Mori E, Miyake H, Wachi A, Takeuchi T, Kazui H, Koyama H (2008) Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: guidelines from the Guidelines Committee of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, the Japanese Society of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 48(Suppl):S1–S23

Johanson CE (2011) Chapter 33. Production and flow of cerebrospinal fluid. In: Winn HR. Youmans: neurological surgery. Elsevier, Philadelphia

Kanno S, Saito M, Hayashi A, Uchiyama M, Hiraoka K, Nishio Y, Hisanaga K, Mori E (2012) Counting-backward test for executive function in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol Scand 126:279–286

Kaplan E (1988) A process approach to neuropsychological assessment. In: Boll T, Bryant BK (eds) Clinical neuropsychology and brain function: research, measurement, and practice. American Psychological association, Washington, DC, pp 129–167

Kiefer M, Unterberg A (2012) The differential diagnosis and treatment of normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Dtsch Aztebt Int 109:15–26

Klinge P, Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Relkin N, Black MP (2005) Outcome of shunting in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus and the value of outcome assessment in shunted patients. Neurosurgery 57:S40–S52

Lamar M, Libon DJ, Ashley AV, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Goldstein FC (2010) The impact of vascular comorbidities on qualitative error analysis of executive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16(1):77–83

Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Klinge P, Relkin N, Black MP (1998) The value of supplemental prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S2-17–S2-28

Mori E, Ishikawa M, Kato T, Kazui H, Miyake H, Miyajima M, Nakajima M, Hashimoto M, Kurijama N, Tokuda T, Ishii K, Kaijima M, Hirata Y, Saito M, Arai H (2012) Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: second edition. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 52:775–809

Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black MP (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S2-4–S2-16

Saito M, Nishio Y, Kanno S, Uchiyama M, Haiashi A, Takagi M, Kikuchi H, Yamasaki H, Shimonura T, Iizuka O, Mori E (2011) Cognitive profile of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 1:202–211

Solana E, Sauquillo J, Junquè C, Quintana M, Poca MA (2012) Cognitive disturbances and neuropsychological changes after surgical treatment in cohort of 185 patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 27:304–317

SPSS Inc. Released (2007) SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. SPSS Inc, Chicago

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Sindorio, C. et al. (2017). Neuropsychological Assessment in the Differential Diagnosis of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. An Important Tool for the Maintenance and Restoration of Neuronal and Neuropsychological Functions. In: Visocchi, M., Mehdorn, H.M., Katayama, Y., von Wild, K.R.H. (eds) Trends in Reconstructive Neurosurgery. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement, vol 124. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39546-3_41

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39546-3_41

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39545-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39546-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)