Abstract

In this chapter we discuss some of the challenges facing teachers of Indigenous children in the early years of schooling, especially around providing opportunities for students to demonstrate existing knowledge. Our focus is on the ways in which teachers are able to show responsive decision making in leading their classes in learning, and the kinds of contexts that result in effective and less effective outcomes in finding out what their students do and do not know. Using Conversation Analytic methods we show here how this may be particularly challenging in a classroom environment where language differences between students and teachers appear to be a factor, but also that even inexperienced teachers can be highly sensitive to occasions for students’ demonstrations of what they know of curriculum content.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Teachers and Indigenous children

- Leadership and pedagogy

- Teacher leaders

- Pedagogy leadership

- Conversation analysis

1 Indigenous Education and Teachers

It is well documented that, despite some gains in recent years, Aboriginal children in Australia still lag well behind the mainstream in school performance (MCEEDYA n.d., p. 7). For example, in 2012 in the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), which is administered across Australia to all Year 3, 5, 7 and 9 students, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children lag behind the mainstream in terms of reaching national minimum standards by around 15–20 percentage points on all parts of the test, with the largest gaps being for grammar/punctuation and numeracy. These differences are compounded when the children live in remote or very remote parts of Australia, where the lag can be as high as 50 percentage points. These results are similar across all 4 years that are tested (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] 2012).

The factors contributing to this state of affairs are complex, and include low school attendance rates, widespread hearing impairment among the children, large numbers of students with special needs, general low-SES (socioeconomic status) factors (including lack of reading materials at home), the lack of the presence of Indigenous culture in Aboriginal schools, and geolocation (metro to remote) (MCEEDYA n.d.). The lack of presence of Indigenous perspectives in Aboriginal schools, together with poor schooling experiences of parents can lead to a disassociation of the school from the community in which the children live, even when the school is physically located in the community.Footnote 1

All of these factors present challenges for teachers in Australian schools with predominantly or totally Indigenous enrolment. Furthermore, the teachers are overwhelmingly non-Indigenous, with tertiary level education by virtue of their profession. Many are recently graduated and thus inexperienced. They have generally received little specific instruction on Indigenous education or working in Indigenous communities, typically one or two courses in their preservice degrees devoted to topics such as Indigenous education, Indigenous knowledge, history and education, or occasionally some aspect of Aboriginal English or language. Some other Indigenous perspectives are embedded in courses, for example in Inclusive Education. Furthermore, many of these teachers have had little or no previous interactions with Aboriginal people in their lives, let alone their workplaces. The lack of prior experience in teaching Indigenous children and working in Indigenous communities may be further compounded by the length of time a teacher may stay working in one school. In more remote schools, teachers often only commit to staying a year or two, providing little incentive to become acculturated into the wider community in which the school is situated.

Clearly more can be accomplished in teacher education and in education policy areas to prepare teachers for working in Indigenous communities (e.g. Department of Education, Training and the Arts [DETE] n.d.), and more can be done to encourage teacher retention, including graduating more Indigenous teachers, as well as developing the skills to implement innovative teaching strategies and contribute to leadership both in the school and in classrooms. In recent years, the MATSITI project (More Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Teachers Initiative, under the auspices of the Australian Council of Deans of Education) has been leading a drive to attract and retain more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander preservice students in schools and faculties of education in universities around Australia (MATSITI 2012). While there are measures in place to improve recruitment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and retention and experience of non-Indigenous teachers, the fact is that currently many teachers are underprepared for teaching Indigenous students.

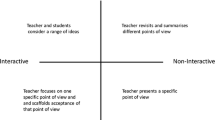

In considering how these usually novice and inexperienced teacher graduates can become leaders in the classroom, and potential leaders in the school, we are led to a view that, while there is an extensive literature on school leadership, there is relatively little research that focuses on teachers as implementers of innovation and as leaders within their classrooms (Jita and Mokhele 2013). Indeed, there appears to be more focus on students as leaders than on teachers (Kythreotis et al. 2010; Dempster and Neumann 2011). There also appears to be some focus within the literature on the effect of school leadership on improving learning, but again, those who lead that learning as it actually takes place in the classroom appear to have been paid little attention. Clearly, though, teachers are leaders in their classrooms, and it seems to us that it is important to understand how the changes and improvements that the school leadership is seeking are actually implemented in the classroom. As Lieberman and Pointer Mace (2009) state, the development of professional leadership must begin with an understanding of what teachers actually know and do in their classrooms, if they are to effect educational reform. Are the young, novice teachers that we worked with up to demonstrating such leadership – in the classroom and in the wider school community? Muijs et al. (2013) are optimistic, stating that teachers were “keen and able to exercise leadership” (p. 767), particularly in implementing new initiatives, and especially when supported by more senior teachers.

Thus our interest in this chapter is how these relatively inexperienced non-Indigenous teachers manage knowledge transmission in their classrooms as they lead their classes in engagement with, and learning of, the content of the curriculum – the practices of the classroom as they occur. A key theme of this research has been to focus on the ways in which students demonstrate their knowledge, or lack of knowledge of curriculum content, teachers’ responses to these demonstrations, and the ways in which teachers navigate the challenges that derive from cultural and linguistic differences between teachers and their students. Here we focus on two aspects of this issue: the ways in which teachers manage to recognise and respond to a student-initiated demonstration of knowledge when there are other competing demands on teacher attention; and where students are asked to demonstrate knowledge, such as in an assessment task. We show how each presents different challenges for teachers.

In student-initiated demonstrations, students must often compete for teacher attention. We provide examples here of the kinds of skills teachers must deploy in these situations so that students have opportunities for feedback on what they claim to know (or not know). Teacher-initiated demonstrations place more on us on the student, who is required to respond, and we show here that it is in these types of exchanges that language differences most come to the fore.

2 Language in Indigenous Education

Before we turn to our study we first outline the ways in which differences between Standard Australian English and the home languages of Indigenous children have been recognised as a challenge for teachers of Indigenous children. We then present a number of examples from our corpus.

It is widely acknowledged that the language varieties spoken by Indigenous children in their families and communities are often significantly different from the Standard Australian English that is the basis of schooling in Australia, and is the language spoken by most teachers (Christie and Christie 1985; Christie and Harris 1985). Language differences are also acknowledged as a factor in poorer school performance as many children lack sufficient proficiency in Standard Australian English to properly engage with the curriculum (MCEEDYA n.d.).

In some regional and remote areas of Australia the language children bring to school may be a traditional language. However, across Australia most Indigenous children do not speak a traditional language as a first language. As has been well documented, the language spoken daily by adults in many communities, and therefore the language first acquired by children, is an English-based variety born out of more than two centuries of contact between Indigenous people and English-speaking colonisers (see Dutton 1983; Troy 1990 for more on the colonial history of these varieties). Some of these varieties were more heavily influenced by traditional languages in their formation, such as Kriol, spoken widely across the top end of the Northern Territory and the Kimberley Region of Western Australia (Munro 2000; Sandefur 1986). Non-Indigenous people encountering Kriol for the first time, including new teachers, often hear Kriol as a traditional language, that is, it does not sound to them like a variety of English. Other Indigenous English-based varieties are closer to Standard Australian English and are often heard as non-standard English – mutually intelligible with Standard Australian English, but with systematically different features of grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary, for example, lack of plural marking on nouns, and no word-initial “h” sound, as in one ’orse, two ’orse. Such varieties are often called “Aboriginal English” (e.g. Eades 1991; Kaldor and Malcolm 1991). Indeed, some teachers report being unable to understand their students, at least upon first arrival at a new school, while other teachers hear their students speaking a kind of “broken” English.

While a full survey of Indigenous English-based language varieties has yet to be undertaken, it is widely acknowledged that there is a considerable range of these varieties across the country, making it difficult to generalise too much about the nature of Aboriginal English (see Young 1997 for a survey of approaches to Aboriginal English). Eades (2013) has recently suggested “Aboriginal ways of speaking” as a better descriptor as it does not presuppose that the language is in fact English.

The term “broken English” is often used in the wider community by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to refer to English-based language varieties, because the grammar and pronunciation of these varieties often run against the norms of the standard language. Such varieties are often treated as poorly learned Standard Australian English, rather than as independent dialects or varieties. The labelling of such varieties as “broken” reflects the general stigma attached to non-Standard English usage (cf. Siegel 2010). Standard Australian English is taught as the only acceptable and “correct” form of the language.

The language ecology of Indigenous communities has a particular bearing on the formal recognition of language matters in the classroom. For example there is clear recognition in the schooling system that children whose first language is a traditional language must learn English as a second language and may have limited exposure to English prior to schooling. Bilingual education programs have been phased in and out of some Northern Territory schools, but typically students who come from Traditional Language-speaking backgrounds are at least recognised as learners of English when they come to school.

It is far more common however for children to come to school speaking a language that is in some sense or other related to English. However, where the home language of children is regularly seen as a type of English, albeit an “Aboriginal” one, there are often few formal acknowledgements that children may not yet have learned Standard Australian English prior to attending school. This situation is compounded by the fact that many children who speak Indigenous English-based varieties are enrolled as speakers of English, perhaps in lieu of a more adequate descriptor of the language they do in fact speak at home.

The stigma attached to home language varieties that are not Standard Australian English may further complicate the issue, as children speaking English-based varieties are often viewed as speaking incorrectly (Siegel 2010). The degree of similarity of these varieties to the Standard may make it difficult for teachers to even recognise what needs to be taught in order to give children the linguistic tools required to properly engage with the Standard Australian English classroom and curriculum. An upshot of this is that when children volunteer or are required to produce demonstrations of knowledge relating to the curriculum, the ways in which language differences may conceal what they know may not be recognised.

3 The Study

Between 2011 and 2013 we conducted a 3-year investigation of language and interaction in a primary school in a Queensland Aboriginal community.Footnote 2 The focus was on the early years of schooling, and we followed three different classes from Prep to Year 3. The overarching goal of the study was to examine the effect of language differences between teachers and students, and the classroom interaction practices, on the children’s learning. To achieve this, we recorded over 50 h of classes over this period, about half of which has been transcribed through the multimodal platform ELAN, which allows for video, audio and transcription tiers to be aligned and to be worked with simultaneously. We used two or three video cameras for each recording, and all children were individually recorded through a voice recorder in a pouch and a lapel microphone to enable us to hear what individual children were saying, even during noisy classroom activities with many people speaking at once.

The approach we have taken to analyse the classroom interaction is Conversation Analysis, which provides us with the tools to examine the classroom talk and how teachers and children reveal their understandings of what is going on in the classrooms, including how they understand curriculum content for learning (Gardner and Mushin 2012; Gardner 2012). We can trace where knowledge is transferred, and ways in which this leads to understanding (or not). The assumption we hold is that understanding is a necessary precondition for learning. Using Conversation Analysis, we examine not only language, but also non-linguistic vocalisations, prosodic overlays on the language, embodied action including gesture, posture, facial expression, and gaze, and how children follow instructions with actions rather than talk, as well as the use of artifacts. The focus of the analysis is on sequences of actions such as question-answer, information-giving and receiving, or instructions sequences, which are all types of sequences in which a response can provide evidence for understanding.

The teachers we worked with in this project were all young, and none was more than a few years out of university. They were also highly dedicated to helping the children to succeed, but faced huge challenges, as noted above. The examples we present below illustrate ways in which they manage to navigate through these challenges and lead the children towards successful learning, despite the interactional and linguistic factors that work to impede smooth communication in responding to students as they demonstrate what they know. There are cases below where the teachers were not successful in leading the children to understanding the learning goals, and we investigate what the factors were that impeded success. On the basis of these kinds of observations, we argue that a better understanding of actual classroom practices can help in the development of strategies for implementing change and the goals of innovations.

The first set of examples highlights the skills teachers need to recognise and respond to students’ attempts to engage with the teacher. In the first place, language differences between the teacher and her Aboriginal students can present a challenge for her to understand what they are saying. In addition, the teacher is often faced with several children simultaneously demanding her attention. The teachers deal with these challenges in different ways. In the first example, which is from a Prep class in which they are working on the butterfly life cycle, the teacher shows considerable skill in accommodating a child’s attempt to make a contribution to the discussion, as she deftly responds to her without taking the focus off the rest of the class, neatly incorporating her response into talk to the whole class. The second example shows a teacher being faced with three children seeking her attention in quick succession, two of whom she responds to, but the third never receives a response, and as a result, her question about procedures in the task is never answered. The third example shows persistence on the part of a child in asking what some symbols on her worksheet mean. In this example, the child’s first attempts at securing attention fail, because the teacher is managing the behaviour of some other children in the class. However, as a result of his persistence and interactional skills, the child eventually secures the teacher’s attention, and the question is answered. These three examples demonstrate the classroom interactional skills that teachers need to meet their students’ learning needs and demands for her attention.

In the second set of examples, taken from individual mathematics assessment tasks, the focus is on how children’s understanding of some basic mathematical concepts is clouded by the differences between the children’s language and the Standard English of the classroom. We found a number of instances in four assessments, each lasting about 15 min, where there was evidence that the children understood the mathematics concepts being tested, but not the language of these concepts as presented to them by the teacher (some of these findings are published in Mushin et al. 2013). The implications here are that if teachers (and assessment task designers more generally) are interested in finding out whether the children understand the concepts rather than the language, then being aware of the interference of the language of mathematics might help them develop better strategies for discovering whether these Aboriginal children understand these concepts or not.

3.1 Managing Student Demands for Teachers’ Attention

In the first example, we see a teacher dealing with an interactionally complex situation. The Prep class is seated around her on the floor, and they are discussing a chart showing the life cycle of the butterfly, from egg to caterpillar to cocoon to fully fledged butterfly (see frame grab in Fig. 15.1). One of the children, Rinnady, notices early on in the extract below that on the chart there is a picture of a butterfly emerging from the cocoon which is placed between the pictures of the cocoon and the fully emerged butterfly. The teacher (Kristy) had not mentioned this as they had worked their way through the life cycle. Rinnady attempts to procure the teacher’s attention in order to point this out, but it is not until the end of the sequence that she is successful.

As the extract begins, the teacher is asking the class to name in order the stages of the butterfly cycle from egg to butterfly.Footnote 3

Transcript 1A

110608:0′10″

1 | T-Kristy: | W hat comes aftuh thuh c a terpillar;= |

2 | Bri : anna? | |

3 | (0.2) | |

4 | Brianna: | > B udderfly.< |

5 | (1.0) | |

6 | T-Kristy: | B’fore [^th[ a :t. |

7 | Rinnady: | [Mis[s ^ N oble(s). |

8 | Seamus: | [Miss |

9 | (0.2) | |

10 | T-Kristy: | Rinn a dy. |

11 | Rinnady: | C’c o o:[n. |

12 | T-Kristy: | [Good g i :rl. |

13 | (0.3) | |

14 | T-Kristy: | W hat comes a :ftuh th’ cocoo: n ,= S ea:mus? |

15 | Seamus: | U h :m:; (1.5) |

16 | Barry: | >A budder˘fly;<= |

17 | Seamus: | =Uhm- (2.0) [b u tterfly.= |

18 | Belinda: | [Miss |

19 | T-Kristy: | =Good. |

20 | (0.4) | |

21 | Belinda | (wi me) |

The teacher’s first question, to Brianna, is about what follows the caterpillar in the butterfly life cycle. Brianna says “butterfly” (line 4), which is not the answer that the teacher is seeking. Rinnady bids and is selected to answer (line 7), and her answer is accepted (line 12). The next question asks what follows the cocoon, and Seamus answers correctly (following Barry’s unsolicited answer in line 16). So at this point, the sequence of stages in the butterfly life cycle has been established, but the picture of the emerging butterfly has been ignored.

Next the teacher turns to the task that the children will be asked to do next, which is colouring in a worksheet with the butterfly life cycle. She focuses on the way they should work: the kind and the manner of colouring in. To answer the first question, “What kind of colouring in should we have?” two students answer, and the teacher selects Brianna; she accepts her answer by repeating it (line 31). The next question is “How should we colour it in?” and six children bid to be selected or call out the answer (lines 38–43). During this period in which children are responding to how they should colour in their worksheets, it becomes apparent that Rinnady has a different agenda (lines 32, 35 and 37).

Transcript 1B

110608:0′27″

22 | T-Kristy: | Oka : y,=^so I : wanna see;=what kind ev |

23 | colouring in sh’d we h a ve on this. | |

24 | (0.3) | |

25 | Brianna: | D[iff’ren-] c u lliz |

Different colours | ||

26 | Cayley: | [G o o:d. ] |

27 | (0.6) | |

28 | T-Kristy: | Bri a nna. |

29 | Brianna: | [ D iff’ren c u ll:[iz; |

30 | Cayley: | [D i :ff’ren c u ll[iz. |

31 | T-Kristy: | [Diff’ren- ^c[ ol ours. |

32 | Rinnady: | [ Ö :::h |

33 | ^M i :ss; | |

34 | T-Kristy: | ^ H ow sh’d [we c olour= |

35 | Rinnady: | [-ihhh |

36 | T-Kristy: | =[it i:[ n :. |

37 | Rinnady: | [a: a ::[y::. |

38 | Lateef: | [ U m:: [nah [^M[ i ss:] |

39 | Cayley: | [ G OO~[OO[::D;] N E [A::T |

40 | Brianna: | [ M E[::(D]EL I [:). |

41 | Rinnady: | [MISS: [ |

42 | Belinda: | [NEA::T |

43 | Spencer: | [M E :[::::; |

44 | T-Kristy: | [^Ne[a:t; |

45 | Lateef: | [( C ha)me? [(gah) M ISS M ISS_ |

46 | Rinnady: | [Dat b u dder f ly nod a :ftuh |

47 | [duh co[coo: n ¿=nat de : re ˘loo(k).] | |

48 | Lateef: | [ M :iss;=[we ‘ a d duh m ake id all ]= |

49 | =d e adly;=e y . | |

50 | (0.5) | |

51 | T-Kristy: | We wanna make it look d e adly. ·hhh See- |

52 | (.) w hat’s ^happened ˘is thuh | |

53 | b u dderfly’s coming o u d ev thuh co c oo:n. | |

54 | [C’n yih see ^tha t ?] | |

55 | Rinnady: | [°C o c o o : n .° ] |

56 | (0.4) | |

57 | Rinnady: | °Yeah.° |

58 | (0.3) | |

59 | T-Kristy: | Coming o u d ev thuh co c oo:n |

The teacher’s “Different colours” in line 31 accepts Brianna and Cayley’s answers, and then in line 32, in overlap with the end of the teacher’s turn, Rinnady makes a bid for a turn (“Öh miss”), followed by a sharp outbreath (line 35, “-ihhh”), and a prolonged “ay” (line 37). The positioning of these three utterances points to her different agenda. Her “Öh miss” is not a response to the teacher’s question in lines 34/36 about how they should colour the worksheet in, but comes as a bid for the teacher’s attention. The first two utterances (“Öh miss” and “ihhh”) come before she has heard or could have understood the teacher’s question, and even the third of her utterances (“ay”) finishes just as the teacher’s question finishes, so this points to these three utterances being independent initiations on the part of Rinnady. What has happened is that she has noticed something.

As she produces the three utterances, she is pointing at the butterfly chart (see Fig. 15.2). At this point, though, she is ignored by all – the teacher and the rest of the class – as they are focused on the teacher’s question about how they should colour in the worksheet, and then on the responses to the question (lines 38–43Footnote 4). In line 43 the teacher accepts the answer “Neat”. At this point, two children start talking – Lateef with a follow-up comment on how “deadly” (awesome) they should work (“Miss, we “ad duh make it all deadly, ey”, in lines 48–49), but just before this, Rinnady had taken her chance to comment on what she had noticed some seconds earlier, “Dat budderfly nod aftuh duh cocoon, nat dere look” [That butterfly’s not after the cocoon, not there look.] in lines 46–47. She had noticed the butterfly emerging from the cocoon on the life cycle chart.

The teacher deals with these two questions deftly. First she responds to Lateef, which is sequentially the more relevant, being an extension of the answer to the previous question, by accepting his contribution through a rephrasing of it in more standard English (“We wanna make it look deadly”). It is at this point that she turns to Rinnady and points out what is happening on the chart: “The butterfly’s coming out of the cocoon. Can you see that?” (lines 52–54). Rinnady repeats “cocoon” softly, and then acknowledges the teacher with “Yeah” (line 57), which in turn in followed by another repeat by the teacher, “Coming out of the cocoon” (line 59).

We have no evidence that the teacher, Kristy, had noticed the first time Rinnady made a bid for her attention, or if she did, she ignored her. The middle of a question-answer sequence involving the whole class is not an appropriate place to deal with a child’s contingent question. Rinnady subsequently waits for the next sequentially appropriate point to report on her noticing, which is immediately after the teacher has rounded off the question-answer-follow-up sequence with her “Neat” in line 44. The teacher’s response to Rinnady’s observation is also positioned at the first opportunity she has, because she first has to deal with Lateef’s sequentially more contiguous observation.

This sequence illustrates the skills that teachers draw upon to manage the complex and demanding problem of not only keeping order in the classroom, but also responding to the children’s contingently and unpredictably arising learning needs. Rinnady noticed that there was something else between the cocoon and the butterfly, and this might have come to nothing. But she persisted in attempting to articulate her noticing, first with her bids for a turn in lines 32–33, 35, and 37 – and then probably again in line 41. This could easily have been missed by the teacher, Rinnady would never have had the puzzle resolved, and a small learning opportunity would have been lost. But the teacher navigated her way through the complexities of the structures of classroom interaction to find a spot where Rinnady’s need to know could be satisfied.

Example 2 is another illustration of how the teacher is confronted with multiple demands on her attention, this time with three children needing her attention in quick succession. She manages to deal with two of them, but the third child, Rinnady, never has her question answered. At the beginning of this extract, the teacher, Alisa, is talking to Belinda, who is sitting immediately to the teacher’s right. Victoria is sitting immediately to her left.

Transcript 2

120607:Yr1:Pt5A:Gp1:0′51″

1 | T-Alisa: | An’: Cayle:y b ought f o u:r l ollies. |

(( To Belinda )) | ||

↑ | ||

Victoria: | 1-> ((Taps teacher on arm)) | |

2 | (0.5) | |

3 | T-Alisa: | So m a ybe ged a ^ d iff’rent co:lour. |

(( To Belinda )) | ||

4 | (4.0) | |

(( Teacher looks down at Victoria’s work )) | ||

5 | Victoria: | O ne:[: |

6 | Rinnady: | 2-> [Miss ^ I got [ d iff’ren cu : lliz¿ |

7 | Victoria | [ t wo:: |

8 | Victoria | ˘ t hree:: (0.6) ˘ f ou:r. |

9 | (0.4) | |

10 | T-Alisa: | G oo:d. |

11 | (0.4) |

In line 1 the teacher, Alisa, is explaining to Belinda how to do the task the class is engaged in. Victoria, at the end of the teacher’s turn in line 1, attempts to win her attention by tactile means, tapping her on the arm. This distracts Alisa, and she dismisses Victoria with a little wave of her hand, as she continues talking to Belinda in line 3. When she finishes with Belinda, she has space to attend to Victoria, and turns to look at what she is doing. After a few seconds, during which she picks up a pencil, Victoria points to four objects on her worksheet (not visible on the video) and says “One, two, three, four” (lines 5 and 8). In the middle of this counting, Rinnady, from the other end of the table, announces to the teacher, “Miss, I got differen’ culliz?” (Miss, I’ve got different colours?), but the teacher is still talking to Victoria, and continues to help her for another 15 s or so. Rinnady’s announcement never gets a response.

In cases such as this, when a teacher is focused on a particular child or group of children, she cannot split her attention to another child. It is not clear whether Alisa has heard Rinnady, but be that as it may, she ignores her. In another study (Gardner 2015), it was found that when students make bids for the teacher’s attention (such as the “Miss” in Rinnady’s turn), the main impediment to the success of such bids (or summonses) is that the teacher is already engaged in talk with another child. Other factors, such as proximity (as we saw with Victoria’s tap on her arm), loudness, posture, or eye contact, are overridden by their attention being with another child. We saw in the first example how the teacher Kristy managed to separate out the various demands on her attention, and adeptly answer to students with adjacent but discrete responses. This is only possible, however, if she is not already engaged in extended talk with others. A further point to note is that Rinnady’s announcement that she has “different colours” is not something that needs urgent attention, which might be the case with disruptive behaviour, or a question relating to a pedagogical or learning matter of consequence to a child.

As example 3 illustrates, disruptive behaviour is indeed something that requires a teacher’s urgent attention, and this can trump a child’s request for help with the task, even though he is impeded from continuing with his work without help. At the beginning of this extract, the teacher, Deanne, is shouting at some of the boys (indicated by the capital letters) in the class to go back to their tables. She is seated at a table with Samuel (to her right), Laurelin (to her immediate left), Stuart (who remains silent throughout this extract) and Malcolm – the boy who is attempting to secure her attention – (two seats to her left).

Transcript 3

111115:Yr1:Pt4a:9′14″

1 | T-Deanne: | DANNY :;=^ D O:N’T (.) D O THAT TO THE |

2 | G A :ME;< Y OU BOYS C’N G O SIT AT YOUR | |

3 | T A BLES;= THANK ^YO U ¿ | |

4 | (1.2) | |

5 | Samuel: | > M iss.=^ d is [one.< |

6 | T-Deanne: | [^YOU GENNA W RECK MY GA:M E ? |

7 | (0.8) | |

8 | Malcolm: | 1-> I ^ p ud it ˘ e re. |

9 | T-Deanne: | DANIE:L ¿ |

10 | (0.4) | |

11 | Malcolm: | 2-> M iss; pud et ^e:r e ? |

12 | (0.2) | |

13 | T-Deanne: | P UD IT D O:WN:;=AN’ G O SIT A T YOUR T A :BLE. |

14 | (1.2) | |

15 | Malcolm: | 3-> A[y m iss. |

16 | Laurelin: | [ I s ^ d is o ne. |

It’s this one | ||

((To Samuel)) | ||

17 | (0.3) | |

18 | Laurelin: | Samue:l:. |

19 | (0.3) | |

20 | T-Deanne: | ·hhh Yeh [e v ’ryone pud]= |

21 | Laurelin: | [DAH O NE:; ]= |

22 | T-Deanne: | =[e:v’rything back down] there;= an’= |

23 | Laurelin: | =[D A H O : : N E : .] |

24 | T-Deanne: | =YOU C’N ˘ G O ^SID AT YOUR T A :BLE.= |

25 | Malcolm: | 4-> =M i :ss;=pud it ^e:r e ? |

26 | (0.7) | |

27 | Malcolm: | 5-> Miss;=^pud it e:re?= |

28 | Samuel: | =Ah ‘ready g o t di:s. |

29 | T-Deanne: | B O [Y:S; I’VE] G I VEN YOU AN INSTRU[CTION:. |

30 | Laurelin: | [(Ah mee) ] |

31 | Samuel: | [No- uh |

32 | (0.2) | |

33 | Malcolm: | 6-> Miss; [pud it ^her e ? |

34 | Laurelin: | [ Y :es;=^dah o :[n:e. |

35 | T-Deanne: | [ D O IT; HA : RRY¿ |

36 | (0.8) | |

37 | Malcolm: | 7-> M iss, (0.2) pud it ^her e ? |

38 | (0.2) | |

3+ | Malcolm: | 8-> Ay m[is s :? |

50 | Laurelin: | [ Y :eh. |

((Laurelin leans over and shows Malcolm | ||

where to put his word)) | ||

41 | (2.5) | |

42 | Laurelin: | Where ^wha’s ˘dah one. |

Where that one is |

Throughout this extract, the teacher is looking over to the other side of the classroom where there is a group of misbehaving boys, and she shouts out instructions and admonishments to them. As can be seen on the video recording of the class, only once does she briefly glance back at the group at the table at which she is sitting (line 27), but she does not answer any of the questions that the children at that table ask.

Just as the teacher finishes telling Danny not to “do that to the game” (lines 1–2), and asking a group of boys to go back to their table, Samuel, a boy at her table, asks her a question about whether he has chosen the “right one” for his task (it is not clear what the “one” is, but it is clear from the video that it is something he needs to know in order to continue with his work). However, the teacher continues to engage in classroom management with the group of misbehaving boys all the way through to line 35 (lines 6, 9, 13, 20/22/24, 29, 35). Laurelin comes in (line 16) to help Samuel by answering the question that he had directed at the teacher. Malcolm, who is also at the teacher’s table, has another question about where to put something on his worksheet, and he also attempts to get her attention (lines 8, 11, 15, 25, 27, and 33). He is actually quite skilful in avoiding overlapping with the teacher’s talk, and mostly repeating his question “Miss, put it here?”, and a few attempts simply to get her attention, “Ay miss.” He also shows he is aware of what the teacher is doing, as he looks around at the boys who are playing up on two occasions, and also looks at her to check what she is doing. However, Deanne is focused the whole time on keeping the class in order, and in the end it is Laurelin, once again, who helps Malcolm out (lines 34, 40, and 42) by leaning over and showing him where to put it. The point here is that because the teacher has to manage behaviour in the class, she is unable to lead the children’s learning or help them with task procedures so that they can make progress with their work.

3.2 How Language Can Conceal Understanding

In the previous section we examined cases where the children initiated, or tried to initiate a question or a demonstration of knowledge (or lack of knowledge), and the challenges that this presented their teachers. In this section we turn to cases where the teacher attempts to initiate a demonstration of knowledge from a child in an orally administered maths assessment task. In these cases, we can show how language difference can impact on demonstrations of knowledge. In particular, these examples demonstrate how children can fail to demonstrate their knowledge not because they do not know an answer, but because language proves to be an impediment. As Abedi and Lord (2001) report, children perform 10–30 % worse on arithmetic problems presented through words rather than in numeric format, and this is compounded when the children are from low-SES backgrounds or are from a non-English background. This suggests that language issues can obscure whether a child understands a mathematical concept or not. In their study, they found that “simplifying the language of math test items helped students improve their performance” (p. 230). The children in the current study are speakers of English as an additional dialect, as well as being low SES, so one might expect that in maths assessment, language may be a factor in their low numeracy proficiency.

As part of our wider project, we investigated the impact of language on some formative one-on-one assessment tasks in a Year 1 classroom. The focus of interest was on demonstrating whether or not a child understood the mathematical concept, or whether language interfered with their understanding. In example 4, the task for the child, Amelia, is to place a number of small blocks she has in front of her into a row of circles on an assessment sheet on the table, one block in each circle.

Transcript 4

Amelia 110908-Yr1-Pt2b

1 | Tea: | M’kay;= c’n y o u put one of those bl o cks, |

(Points to blocks)) | ||

2 | =in e a ch of these h o ops, for ^me? | |

((Sweeps finger over assessment sheet)). | ||

((Another child approaches table to ask teacher a question)) | ||

((Amelia picks up pencil, poises to write on page)). | ||

(3.5) | ||

3 | Ame: | Wh a t Miss,= wh a t you gotta ^pud in? |

((Looks up at teacher)) | ||

4 | (0.2) | |

((Points to the block on top of a pile)) | ||

5 | Tea: | C’n you p u t o ne of the:se blocks, |

6 | =in e ach of those circ l es:?=Yep. | |

((Amelia picks up block, shows teacher)) | ||

7 | (1.0) | |

((Amelia puts block on circle, looks at Teacher)) | ||

8 | Ame: | origh’? |

9 | (0.2) | |

10 | Tea: | Y e ah? |

11 | (2.1) | |

((Amelia takes hand off block, moves back in chair, | ||

looks at teacher)) | ||

12 | Tea: | In: e ach of the c i rcles,=Amelia¿ |

13 | (0.2) | |

((Amelia picks up block from circle, looks at teacher)) | ||

14 | Ame: | Ah dr a :w dem ^Miss?= |

15 | Tea: | N o t dra:w i ng¿ (.) |

((Takes pencil away from Amelia)) | ||

16 | Put (.) one bl o ck¿= in e ach of those | |

17 | circles,=°for me°. | |

18 | (1.5) | |

((Amelia looking and smiling at teacher)) | ||

19 | Ame: | °Mm¿° |

20 | Tea: | M’k h a:y. |

21 | (1.3) | |

((Teacher removes the block from the page)) |

In this example, the teacher begins by asking Amelia the question, “Can you put one of those blocks in each of these hoops for me?” As the teacher asks her question, she points to the blocks on the table, and sweeps her finger over a row of circles on a page of the assessment sheet. The teacher next deals quickly with a question from another child who has approached her. Meanwhile Amelia has picked up her pencil and is poised to write – the first indication that she has not understood the teacher’s instructions. After a few seconds, she asks what she is required to do (“What miss, what you gotta put in?” in line 3). The teacher repeats her question with some modification, the main one being to change “hoops” to “circles”. Amelia understands “circles,” and she picks up a block showing it to the teacher, then places the block on a circle, and asks, “Origh’?” (“Alright” in line 8), seeking confirmation that she has been successful. The teacher appears to Amelia to have accepted this, as she moves back in her chair and looks at the teacher, thereby disengaging from further activity in the task. This is followed by a prompt from the teacher, “In EACH of the circles, Amelia?” (line 12, with strong emphasis on “each”). This leads to further confusion, as Amelia asks if she should draw them (“Ah draw dem Miss?” in line 14), to which the teacher replies “Not drawing.” Next comes the teacher’s fourth version of the instruction, “Put one BLOCK in each of those circles for me” (lines 16–17), but Amelia remains unsure (her rising “Mm?” in line 19). At this point the teacher terminates the task to move on to the next one.

What can we say about how much Amelia has understood? After the first repetition of the question in lines 5–6, Amelia has understood enough to know that she is required to place a block on a circle. This would have been correct if the instruction had been something like, “Can you put one block in those circles?”, so the crucial missing word, and the word Amelia appears not to have understood, is “each”. Her misunderstanding may have been compounded by the instruction mentioning one block, as she did put one block on a circle. What we can thus say is that it is very likely that Amelia did not understand the word ‘each’. What we cannot say is that she does not understand the distribution concept of each as referring to two or more objects, separately identified, but for the purposes of the assessment, she is not demonstrating understanding. However, it is quite possible that she does in fact understand the concept of distribution of objects.

With Amelia, the teacher did not probe sufficiently to establish whether or not she had understood the concept being tested. With Gary in the next example, he similarly is not given the opportunity to show how far he was able to count – and in fact there is evidence that he was able to count further than he did. It begins with the teacher asking him to count for her.

Transcript 5

Gary 110908-Yr1-Pt2b:0′6″

1 | Tea: | Can you c o unt for me,= G a ry? |

2 | (1.3) | |

3 | Gar: | Um, |

4 | (1.4) | |

5 | Tea: | C o unt for me; |

6 | (0.8) | |

7 | Gar: | On:e¿= two; (0.8) shree;= four; |

8 | (1.1) | |

9 | Tea: | What comes after f o u:r; |

10 | (0.5) | |

11 | Gar: | F i ve.= |

12 | Tea: | =Keep g o in, |

13 | (0.6) | |

14 | Gar: | °F:i:[:: v e ¿ ° ] |

15 | Tea: | [What comes a f]ter f i ve; |

16 | (1.4) | |

17 | Gar: | Six |

18 | (1.0) | |

19 | Gar: | °S[i x . °] |

20 | Tea: | [Wha’ co]mes a fter s i x; |

21 | (0.7) | |

22 | Gar: | U- s e ven.= |

23 | Tea: | =What comes after s e ven. |

24 | (0.7) | |

25 | Gar: | Eight.= |

26 | Tea: | =What comes after e ight. |

27 | (0.6) | |

28 | Gar: | Nine; |

29 | (0.2) | |

30 | Tea: | What comes after N I NE. |

31 | (0.5) | |

32 | Gar: | T e n:;= |

33 | Tea: | What comes after t e n. |

34 | (0.8) | |

35 | Gar: | °Ahl e (v)en° |

36 | (1.7) | |

37 | Tea: | >D’y kn o :w wh’t comes< after t e n? |

38 | (1.2) | |

39 | Gar: | e:r, |

40 | (5.0) | |

41 | Gar: | >Twenny o ne<.= |

42 | Tea: | =M’g a y. |

After the teacher repeats “count for me,” Gary counts up to four. She then prompts him to say what comes after four, and then what comes after the other numbers up to 10. Each time Gary responds, reasonably enough, with the next number in sequence, rather than count continuously as far as he is able. When he is asked what comes after 10, he says – very softly – “eleven”, pronounced more like “ahlehen.” The teacher has either not heard (because of the softness) or not understood (because of the non-standard pronunciation) what he has said, or perhaps because of a combination of both. So she repeats the question, adding “D’you know” to the start of the question (line 37). Gary hesitates, and after several seconds revises his answer to twenty-one (“twenny one” in line 41). This marks the end of this part of the assessment and they move on to the next part.

Gary initially provides the correct answer, but then changes it to an incorrect one. The consequence has been that he has not revealed his knowledge of counting for this diagnostic test. To this extent this is similar to extract 1 above where Amelia had not revealed whether she understood the mathematical concept of distribution. But why did he change his answer? We suggest that the problems can be traced to certain norms of classroom interaction, specifically the way in which teachers ask questions to which they know the answer. Question-answer sequences are pervasive in classrooms, the so-called Initiation-Response-Follow-up (IRF) sequences (Mehan 1979), where the teacher asks the question, a student provides an answer, and the teacher evaluates the answer in a variety of ways in the follow-up (Lee 2007). The follow-up is a rich resource for teachers, in which they may accept an answer, reject it, or probe further to draw out the correct (or at least sought for) answer from the student. Accepting is regularly done through a positive assessment of the answer, such as “Good”, or a repetition of the answer. A repetition of the question, on the other hand, generally indicates that the answer is not the one that the teacher is seeking. It would seem that Gary has interpreted her repetition of the question as a rejection of his answer, and so he has changed his answer from “eleven” to “twenty-one”.

What is potentially of interest to those who develop assessment tools such as the ones used in this task is that they need to be clear whether they are assessing mathematical concepts or the language of mathematics. The Amelia example shows that not understanding a crucial word (“each”) can potentially mask whether the child understands the concept behind the word. In her case it is unclear whether she knew the mathematical distribution concept that “each” codes, though we could see that this word caused her to fail to complete the assessment task correctly. The Gary example shows that conventional, institutional practices, such as question-answer-follow-up, can lead the child to believe that his response is incorrect, thus concealing what he in fact knows. He showed that he was capable of counting at least to 11 (and quite likely beyond), but because of a mis-hearing by the teacher, he was not given the opportunity to show how far he could have counted.

We have seen in the two examples from maths assessment above how language can hinder learning, or demonstrations of knowledge. In the first example, it was a word, “each,” that caused Amelia to execute the task incorrectly. In the second example, it was the sequential positioning of a repeat question that causes Gary to infer that his first answer had been incorrect. These are examples of the teacher not leading learning or assessment successfully, and if teacher educators and school leaders are aware that this goes on in their classrooms, the opportunity arises to raise awareness and to change classroom practice.

4 Conclusion

Understanding language use, interactional practices and communication styles in the classroom will not by itself turn these children into successful school students. However, we can see how teachers and students are constrained by the structures of classroom interaction and differences in language varieties. Requirements of assessment practices can mean that opportunities for revealing what children really know may be lost. On the other hand, those very structures of classroom interaction, such as the pervasive question-answer-follow up sequence, can also provide an orderliness through which competing learning demands of students can be dealt with, as in the first three examples. It is most unlikely that teachers in classrooms such as those in which the recordings for this project were made will be able to deal with all the learning opportunities that potentially arise. Nevertheless, as we saw with the teacher Kristy, even relatively inexperienced teachers may be able to retrieve moments for learning that could easily have been lost – by recognising, even if without being able to articulate the complexities of the structures of classroom talk, how to use those structures to find opportunities to respond to learning needs, and thereby lead their teaching and the children’s learning. There are, though, limits to what a teacher can do to retrieve all moments of potential learning, such as when competing and multiple demands for her attention exceed her ability to respond, or when urgent matters such as behaviour management draw her attention away from individual children.

Teachers have very demanding jobs. Their attention is constantly distributed around the class, to different students with their different demands. They have to manage a very challenging environment. Teachers would benefit from being able to reflect on the consequences of contingencies in the classroom, and examples such as those presented here could help such reflection. Through studies that pay attention to the intricacies of classroom interaction such as this one, understanding classroom interaction practices, such as question-answer-follow up and the role of the third position feedback, or the effect of language masking children’s real knowledge, could be an additional tool for teachers in dealing with the demands of the complex social milieu of the classroom.

Notes

- 1.

The situation is depressingly similar to that encountered by Christie and Harris (1985) nearly 30 years ago, when they wrote that factors the lack of success of Indigenous children in schools in Aboriginal communities in northern Australia included “poor attendance rates, the lack of a literate or schooled tradition in the home, “motivational” differences, curriculum materials unsuitable for the cross-cultural setting, high staff turnover, and lack of specialist teacher training” (p. 81).

- 2.

This study was funded through an Australia Research Council Linkage Project (‘Clearing the path towards literacy and numeracy: Language for learning in indigenous schooling.’ LP100200406). We thank the school and community, and the Queensland Department of Education, Training and Employment for their support of this project.

- 3.

Names of children and teachers have been changed.

- 4.

It is worth pointing out that Rinnady’s “Miss” in line 41 is unlikely to have been a bid to answer the teacher’s question, but is more likely to have been another attempt to secure a turn so that she could report to the teacher on her noticing, which was finally produced in lines 46–47.

References

Abedi, J., & Lord, C. (2001). The language factor in mathematics tests. Applied Measurement in Education, 14(3), 219–234.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2012). NAPLAN achievement in reading, persuasive writing, language conventions and numeracy (National Report for 2012). Sydney: ACARA.

Christie, M., & Christie, M. (1985). Aboriginal perspectives on experience and learning: The role of language in Aboriginal education. Melbourne: Deakin University Press.

Christie, M., & Harris, S. (1985). Communication breakdown in the Aboriginal classroom. In J. Pride (Ed.), Cross-cultural encounters: Communication and miscommunication (pp. 81–90). Melbourne: River Seine.

Dempster, N., & Neumann, R. (2011). Pathways to formal and informal student leadership: The influence of peer and teacher-student relationships and level of school identification on students’ motivations. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 14(1), 85–102.

DETE (Department of Education, Training and the Arts) (DETE). (n.d.). Foundations for success: Guidelines for an early learning program in Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities. Queensland Government.

Dutton, T. (1983). The origin and spread of aboriginal Pidgin English in Queensland: A preliminary account. Aboriginal History, 7(1–2), 90–122.

Eades, D. (1991). Aboriginal English: An introduction. Vox, 5, 55–61.

Eades, D. (2013). Aboriginal ways of using English. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Gardner, R. (2012). Conversation analysis in the classroom. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 593–611). Oxford: Blackwell.

Gardner, R. (2015). Summons turns: The business of securing a turn in busy classrooms. In P. Seedhouse & C. Jenks (Eds.), International perspectives on classroom interaction (pp. 28–48). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gardner, R., & Mushin, I. (2012). Language for learning in indigenous classrooms: Foundations for literacy and numeracy. In R. Jorgensen, P. Sullivan, & P. Grootenboer (Eds.), Pedagogies to enhance learning for indigenous students: Evidence-based practice (pp. 89–104). Heidelberg: Springer.

Jita, L. C., & Mokhele, M. L. (2013). The role of lead teachers in instructional leadership: A case study of environmental learning in south Africa. Education as Change, 17(SI1), S123–S135.

Kaldor, S., & Malcolm, I. (1991). Aboriginal English – An overview. In S. Romaine (Ed.), Language in Australia (pp. 67–83). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kythreotis, A., Pashiardis, P., & Kyriakides, L. (2010). The influence of school leadership styles and culture on students’ achievement in Cyprus primary schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 48(2), 218–240.

Lee, Y.-A. (2007). Third position in teacher talk: Contingency and the work of teaching. Journal of Pragmatics, 39, 180–206.

Liebermann, A., & Pointer Mace, D. (2009). Making practice public: Teacher learning in the 21st century. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 77–88.

MATSITI (More Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Teachers Initiative). (2012). MATSITI Project Plan 2012–15. Retrieved November 8, 2013, from http://matsiti.edu.au/about/project-plan/

Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs (MCEEDYA). (n.d.). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education action plan, 2010–14. Retrieved October 23, 2013, from http://scseec.edu.au/Publications.aspx

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons: Social organization in the classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Muijs, D., Chapman, C., & Armstrong, P. (2013). Can early careers teachers be teacher leaders? A study of second-year trainees in the Teach First alternative certification program. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(6), 767–781.

Munro, J. M. (2000). Kriol on the move: A case of language spread and shift in Northern Australia. In J. Siegel (Ed.), Processes of language contact: Studies from Australia and the South Pacific (pp. 245–270). Montreal: Fides.

Mushin, I., Gardner, R., & Munro, J. (2013). Language matters in demonstrations of understanding in early years mathematics assessment. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 25(3), 415–433.

Sandefur, J. R. (1986). Kriol of North Australia: A language coming of age. Darwin: Work papers of Summer Institute of Linguistics-AAB A:10.

Siegel, J. (2010). Second dialect acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Troy, J. (1990). Australian Aboriginal contact with the English language in New South Wales: 1788–1845. Pacific Linguistics B-103.

Young, W. (1997). Aboriginal English (Report to the National Languages and Literacy Institute of Australia). Sydney: NLLIA Style Council Centre, Macquarie University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Transcription Conventions

Appendix: Transcription Conventions

(0.0) | silences measured in tenths of a second |

((Words)) | descriptions of actions of speakers are placed between double parentheses |

= | latching: adjacent turns with no gap and no overlap between them |

? | “question” intonation (i.e. rising pitch) |

. | “period” intonation (i.e. falling pitch) |

, | “comma” intonation (i.e. level pitch) |

underline | syllables delivered with stress or emphasis by the speaker |

CAP | stretches of speech delivered more loudly than the surrounding talk |

°word° | stretches of speech delivered more softly than the surrounding talk |

wo:rd | the lengthening of a sound is marked through colons: each colon |

represents approximately the length of a beat | |

>words< | talk that is faster than its surrounding talk |

<words> | talk that is slower than its surrounding talk |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gardner, R., Mushin, I. (2016). The Impact of Interaction and Language on Leading Learning in Indigenous Classrooms. In: Johnson, G., Dempster, N. (eds) Leadership in Diverse Learning Contexts. Studies in Educational Leadership, vol 22. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28300-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28302-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)