Abstract

Common peroneal nerve pathology is the most common lower extremity mononeuropathy. Dysfunction of this nerve is a cause of foot drop and anterolateral calf sensory disturbances and pain. The pattern of pain and weakness, as well as the mechanism of injury, are clues as to the etiology. This chapter describes the diagnosis and treatment of common peroneal nerve entrapments.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Common peroneal nerve

- Common fibular nerve

- Foot drop

- Calf pain

- Peroneal tunnel

- Fibular tunnel

- Peroneus longus muscle

- Biceps femoris muscle

Introduction

Entrapment of the common peroneal nerve (CPN) is one cause of CPN dysfunction (one of the most common focal neuropathies of the lower extremities), although CPN injuries are usually due to trauma [1, 2]. In one report of patients seen for paresis of the foot dorsiflexors (foot drop), CPN lesions accounted for 31 % of those originating in the peripheral nervous system; of these, 76 % were the result of trauma [3]. They are particularly common in younger men, probably because younger men are injured more frequently [3, 4], while older women have more adipose tissue, a significant source of protection for the CPN near the knee [5]. In one series of operative decompressions of the CPN, 92 % of the patients presented with weakness, 92 % had a sensory disturbance, and 84 % had pain, all of which are sources of substantial disability [6].

In 1998, the peroneal nerve was renamed the fibular nerve, to avoid confusion with the perineal pelvic region; but the name change has not been commonly accepted, and both terms are used [7].

Clinical Presentation (Table 67.1)

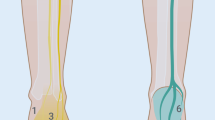

Patients with CPN compression usually present with foot drop, a significant disability, which causes a “slapping” gait, toe dragging, problems in walking and climbing stairs, and frequent falling. They also often have decreased sensation, tingling, numbness, or burning on the lateral lower leg (Figs. 67.1 and 67.2), down to the top of the foot [11] (Fig. 67.3). When pain is present, it typically worsens (and may radiate proximally) with physical activities, such as walking, jogging, running, or squatting. As with many peripheral nerve entrapments, symptoms differ depending on the origin and extent of the problem (Fig. 67.4).

The most common cause of CPN injury is trauma [3, 4]. Open and blunt force injuries of the lateral knee and open or arthroscopic knee surgery can compromise CPN integrity [21]. There is an approximately 1 % incidence of CPN injury after tibial plateau fractures [22]. Sedel and Nizard [23] described 17 cases of traction injuries to the CPN; the initial injury for all the cases was a severe varus deformity of the knee. Foot drop may also be the result of a “straightforward acute inversion sprain of the ankle” [8, 15]. In a series of 66 patients with ankle sprains, 86 % of the patients with grade III sprains and 17 % of the patients with grade II sprains had evidence of CPN injury on needle EMG (see section “Diagnostic tests” below). Traction on the peroneus longus muscle (PL) likely stretches the CPN and compresses it at the fibular neck; hematoma from the injury may aggravate the situation. Night calf cramps are common [24].

Prolonged extrinsic pressure is another significant cause of CPN neuropathy. This can be discovered postoperatively in patients who had been in the lateral decubitus or lithotomy position during surgery. The CPN may be susceptible to damage in patients who have lost a significant amount of weight, particularly if they are confined to bed where the natural position of the leg is in external rotation with knees flexed [22]. Twenty percent of 150 cases of peroneal neuropathy were associated with weight loss and dieting [20]. CPN palsies were noted in World War II prisoners of war who lost 5–11 kg [20].

Sitting for prolonged periods with legs crossed, prolonged squatting (“yoga foot drop”) [14], and pressure to the lateral knee during deep sleep all have been reported to cause CPN injury [11]. One study identified common peroneal injury after maintaining the same posture for an average of 124 min [11]. When there is evidence of CPN compression, medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus or toxin exposure that increase the vulnerability of the nerve should be considered. CPN is the most common low limb mononeuropathy in athletes, most likely due to compression by the peroneal longus muscle (PL) (also known as the fibularis longus muscle) [20].

Space-occupying lesions such as intraneural ganglion cysts [25], vascular aneurysms [18], or lipomas [26] can also compress the CPN.

Anatomy (Table 67.2)

The CPN is the smallest of the two main branches of the sciatic nerve (see Chap. 65), about half the size of the other branch, the tibial nerve (see Chap. 73) (Fig. 67.5). It provides motor and sensory function to the lower leg, dorsum of the foot, and toes. In or near the popliteal fossa, the CPN gives off three branches: the nerve to the short head of the biceps femoris muscle (BF); the lateral sural cutaneous nerve (lateral cutaneous nerve of the calf), which supplies sensation to the upper lateral calf (see Chap. 72); and the sural communicating branch, which travels posteriorly to join the medial sural cutaneous nerve to form the sural nerve (see Chap. 71) (Fig. 67.6). The CPN follows the medial edge of the BF to the lateral popliteal fossa to the fibular head (Fig. 67.7), where it changes its downward course to wind laterally around the neck of the fibula between the two heads of the PL, dividing into its terminal branches. The CPN gives off some muscular branches, and then all of the branches cross the intermuscular septum from the lateral to the anterior compartment.

Dissection of the posterior thigh and calf (Modified from an image from Bodies, The Exhibition, with permission). A biceps femoris muscle, B sciatic nerve, C peroneal division, D tibial division, E common peroneal nerve, F lateral sural cutaneous nerve, G sural communicating branch, H sural nerve, I medial communicating branch, J gastrocnemius muscle, K semitendinosus muscle, L semimembranosus muscle, M gracilis muscle, (1) fibular tunnel, (2) entrapment site between the biceps femoris and gastrocnemius muscles (Image courtesy of Andrea Trescot, MD)

Pain pattern of a patient with presumed anterior recurrent peroneal nerve entrapment. Pat patella, TT tibial tubercle, Fib fibula, CPN common peroneal nerve, SPN superficial peroneal nerve, DPN deep peroneal nerve, ARPN anterior recurrent peroneal nerve, X site of tenderness (Image courtesy of Peter Mouldey, MD; modified by Andrea Trescot, MD)

Most commonly, the very proximal muscular branch (to the tibialis anterior muscle) pierces the septum directly, while the main nerve and remaining muscular branches traverse an osteofibrous hiatus, opening between the septum and the fibula [28]. It continues into the foot as the superficial peroneal nerve (SPN) (see Chap. 68) and the deep peroneal nerve (DPN) (see Chap. 69). CPN dysfunction results in weakness of foot dorsiflexion and eversion, as well as sensory changes in the lateral aspect of the leg and dorsum of the foot and toes.

There is also a variant called the accessory peroneal nerve (accessory fibular nerve) that branches from the superficial peroneal nerve (superficial fibular nerve) (see Chap. 68) underneath the peroneus brevis muscle (fibularis brevis muscle), traveling to the foot, posterior to the lateral malleolus [20]. There have also been descriptions of the CPN separating from tibial nerve proximal to the piriformis and passing between the heads of the piriformis muscles, with the tibial nerve passing inferiorly [29].

Entrapments

The CPN is most commonly entrapped at the peroneal tunnel (fibular tunnel), where the nerve winds around the fibular neck (Fig. 67.6 Site 1) [27]. The entrance to this tunnel was first described in 1973 as a “fibrous arch located on the lateral border of the fibula about 1 to 2 cm inferior to its head…,” consisting of fibers from combined aponeuroses of the soleus and PL muscles [30]. At this location, the CPN lies on the bone, protected only by the fascia and skin, and thus is vulnerable to even modest external compression. The peroneal tunnel is considered to have both superficial and deep parts [16, 27], both of which must be released for successful neurolysis [6]. More recent detailed dissections have raised questions about the functional anatomy of this area [31]; further work is needed to resolve the differences.

The main trunk of the CPN may also become trapped in a tunnel between the gastrocnemius and biceps femoris muscles (Fig. 67.6 site 2) [5]. Also, if there is a high division of the sciatic nerve and its peroneal division pierces the piriformis muscle, the CPN can be trapped there, especially if the patient has piriformis hypertrophy or scarring [27].

In 1972, Haimovici [13] described a series of 48 patients (60 limbs) with “exquisite” tenderness along the lateral aspect of the popliteal space, radiating down the lateral calf, which he attributed to the entrapment of the CPN branches (lateral sural nerve and sural communicating branch) as they pass through fascial openings. Although the pain was in a CPN pattern, there is no motor weakness.

There is also a potential entrapment of the CPN by an occasionally occurring accessory sesamoid bone (called a fabella) [32] near the attachment of the lateral gastrocnemius muscle, which is found in 8.5 % of the population [33]. On physical examination, there may be discrete tenderness in the lateral popliteal fossa, often accompanied by a 1 cm tender nodule.

An under-recognized branch of the CPN is the recurrent auricular branch (also known as the anterior recurrent peroneal nerve), which exits the fibular tunnel with the CPN but travels cephalad to the lateral patella [34]. This entrapment causes pain below the patella, which may be misdiagnosed as patellar tendinopathy (Fig. 67.7). The presence of pain localized to the lateral border of the proximal patellar tendon and the presence of increased peroneus muscle tone may help to differentiate these conditions [34].

The cutaneous branches of the CPN (the lateral sural cutaneous and sural communicating nerves) (Fig. 67.6) may become entrapped in the popliteal fossa [13]. These branches cross the popliteal fossa and become subcutaneous behind the knee joint. Patients with cutaneous branch entrapment describe an acute onset of a sensation of heaviness or pain behind the knee or on the lateral leg after prolonged sitting. In contrast to patients with CPN entrapment, they had no motor symptoms and few sensory changes. Fibrous bands constricting the CPN near the fibular head and proximal PL have been reported at operation in patients with CPN palsy [6, 35] but not in normal cadavers [27].

It is also important for the clinician to remember the potential for a “double crush” phenomenon (see Chap. 1). Ang and Foo [36] described a patient with leg pain and paresthesias who underwent spinal surgery for lateral spinal stenosis and yet had persistent leg pain postoperatively. The patient was subsequently found to have peroneal muscle herniations at two separate locations that were entrapping the CPN. That case report went on to encourage clinicians to consider distal entrapments as an additional or potentially primary diagnosis.

Physical Exam

The physical examination should begin with a general evaluation of the leg, looking for signs of trauma, surgery, or vascular insufficiency. The strength of the leg muscles and sensory examination should be compared to the unaffected side. With CPN dysfunction, the weakness of ankle dorsiflexion and foot eversion is likely (“foot drop”) and is considered the hallmark finding (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7-L9MFRXD8 for a video of the gait disturbance – with permission). Patients may complain of more subtle tripping or catching their toe during ambulation [20]. Sidey described 23 patients with CPN entrapment confirmed at surgery; 18 patients either described or were found to have ankle weakness [37]. Sensory disturbances of the skin over the lateral distal lower leg and dorsum of the foot are also common but may be absent [20]. Sensation on the sole of the foot should be normal. Provocative maneuvers include Tinel’s sign with palpation over the lateral popliteal fossa (Fig. 67.8) and superior fibula, as well as reproduction of the pain with palpation along the fibular tunnel (Video 67.1) (Fig. 67.9). These findings are potentially increased with the foot in plantar flexion and inversion, which are positions that stretch the CPN. Pain or paresthesias with either of these tests indicate probable CPN compression and the need for further investigation. There can also be a slightly more proximal site of tenderness posteriorly at the lateral edge of the popliteal fossa at the level of the knee joint line and at the level of the takeoff of the lateral sural cutaneous nerve and the sural communicating nerve [13] (Fig. 67.6). Dorsiflexion weakness (but not usually pain) may also be the presenting symptom of conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [19]. Signs and symptoms of CRPS may be present [38].

Posterior knee, location of proximal tenderness of the common peroneal nerve. Image modified from Haimovici [13]. (Image courtesy of Andrea Trescot, MD)

For the anterior recurrent peroneal nerve (ARPN), the physical exam will show no sensory or motor loss; resisted eversion and plantar flexion are sometimes painful, and superior tibiofibular subluxation or inferior tibiofibular subluxation can be found. There is also a tender spot located at the lateral border of the proximal insertion of the patellar tendon (Fig. 67.7). The triad of symptoms associated with the anterior recurrent peroneal syndrome [34] includes the “exact painful spot, peroneus muscular hypertonicity, and some degree of varied subluxation” [34]. The list of differential diagnoses is found on Table 67.3.

Diagnostic Tests (Table 67.4)

Electrodiagnostic studies are important for diagnosis and prognosis. Motor studies are usually performed at the extensor digitorum brevis and tibialis anterior muscles [20]. Interestingly, muscles supplied by the DPN (deep fibular nerve) are more likely to be affected, since the nerve fibers of the DPN are located anteriorly and are therefore more sensitive to compression [20]. Any compound muscle action potential response from tibialis anterior muscle or extensor digitorum brevis muscle EMG is associated with a likely positive outcome of treatment (81 % and 94 %, respectively). Even those without a response had an approximately 50 % chance of a good result from treatment [40]. Many protocols for surgical treatment of CPN dysfunction require preoperative electrodiagnostic studies [6, 16, 41].

MRI technology continues to develop, and high-intensity MRIs are now available that can visualize the larger nerves. In addition to showing direct evidence of nerve injury and signs of muscle denervation [2], the new MRI technology can be used for investigation of anatomic variation in large numbers of asymptomatic individuals [5].

Identification and Treatment of Contributing Factors

Peroneal neuropathy has been associated with a variety of endocrine and metabolic conditions such as diabetes, alcoholism, thyrotoxicosis, or vitamin B deficiency [42], so blood work may be indicated for diagnosis and treatment.

In-shoe devices to maintain the foot in eversion may improve biomechanics and decrease symptoms of CPN dysfunction [38]. If this is insufficient, an ankle foot orthosis (AFO) may be needed to manage foot drop. Reife and Coulis described a patient with persistent leg pain after spinal surgery; physical exam was consistent with common peroneal entrapment, and the symptoms resolved after the patient was counseled to stop crossing her legs [42].

Injection Technique

Care must be taken when doing injections of the CPN. Because of its exposed location, there is a risk of post-procedure foot drop and damage to the nerve with the needle.

Landmark-Guided Injection

After an appropriate skin prep, the CPN is localized at the fibular head and stabilized, using the non-injecting hand. With the injecting hand, the needle (25–27 gauge) is advanced slowly and obliquely to the bone to avoid deposit of steroid superficially in the skin (Video 67.2) (Fig. 67.10). The use of a short-bevel needle and a peripheral nerve stimulator can increase the efficacy and safety of this injection. A small volume of local anesthetic with a deposteroid may be injected into the area of maximum tenderness as an aid to localization of the source of sensory symptoms and treatment of the pain generator [39].

Fluoroscopic-Guided Injection

There are no published fluoroscopic-guided techniques, though the fibular head is a good fluoroscopic landmark (Fig. 67.11).

Ultrasound-Guided Injection

The superficial location of the CPN and its close approximation to the fibular head are clear advantages to the use of ultrasound guidance (US) for injections of the CPN. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position, with the symptomatic knee up and slightly flexed. A linear transducer is placed over the sciatic nerve in the posterior thigh and directed distally to the popliteal fossa (Fig. 67.12), to identify the split of the sciatic nerve into the tibial and common peroneal nerves (Fig. 67.13). The probe is then used to trace the CPN as it wraps around the fibular head, allowing visualization of the CPN posterior and lateral to the fibula (Fig. 67.14). Using an in-plane technique, the needle is advanced from the posterior aspect of the probe (Fig. 67.15). When the needle is near the nerve, 5–10 cc of local anesthetic can provide a surgical block. Of concern with this injection is the possibility of nerve injury by the needle or by a large volume of local anesthetic compressing the CPN against the bone in the low-volume fibular tunnel [43]. Diagnostic injections should be limited to no more than 2 cc of local anesthetic and deposteroid. Patients must be warned of the possible, even probable, foot drop associated with this injection.

Neurolytic Techniques

Cryoneuroablation

Because the CPN has such a significant motor component, it is rarely an appropriate neurolysis target. However, when there are specific conditions that require temporary neurolysis (such as neuroma treatment just distal to the fibular head or phantom limb pain), cryoneuroablation with the use of an AFO splint to manage the foot drop might be appropriate (personal communication, Andrea Trescot, MD), since the nerve, and therefore motor function, will return within 3 months. Although it has not been described, there is a theoretic potential for neurolysis of the anterior recurrent peroneal nerve. The cryoprobe is placed inferior to the fibular head, and stimulation (and possibly ultrasound) is used to identify the nerve (Fig. 67.16) (see Chap. 8).

Radiofrequency Lesioning

There are no reported cases of radiofrequency lesioning of the CPN, most likely because of the significant motor component of this nerve.

Neurostimulation

Because of the limitations of neurolytic techniques in this region, there is a rationale for the use of peripheral nerve stimulation (see Chap. 9). Unfortunately, generator placement has been a potential problem, usually requiring placement in the groin or buttocks (Fig. 67.17). Lynch et al. described creating a pocket between the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles [44]. New technology (SpineWave®), where the receiver is incorporated into the lead itself, may solve this problem.

Peripheral nerve stimulation for peroneal and saphenous neuralgia. (a) Percutaneous trial of bilateral peroneal and saphenous peripheral stimulator leads, (b) planning for lead and generator placement for peroneal peripheral stimulator, (c) preparing a thigh pocket for a peroneal peripheral nerve stimulator (Images courtesy of W. Porter McRoberts, MD)

Surgical Techniques

Surgery, either neurolysis or grafting, is the most common and most effective treatment for CPN entrapment [39]. Many authors state that surgery is indicated if there is no return of function after 3–4 months, especially in cases of severe paresis [9, 35, 39], and that time to recovery was shorter with surgical release than with nonoperative rehabilitation [41]. As with neurolysis at other locations, it is important to release all entrapment sites; for the CPN trapped near the fibular head, this entails release of both the superficial and deep fibrous arches [6].

Sidey described 23 patients with CPN entrapment who underwent nerve release at the fibular head under local anesthetic; 20 of these patients had relief “rapidly and completely” [36].

Some CPN injuries may require nerve grafting instead of simple neurolysis. Sedel and Nizard [23] described 17 consecutive patients with traction injuries of the CPN; they were treated with grafts from sural nerves, but only 37.5 % had satisfactory results. The length of the graft required is an important factor in recovery. Forty-three percent of patients with 6–12 cm grafts had good outcomes, whereas only 25 % of those with 13–24 cm grafts did well [9]. If neurolysis and grafting are not successful, tendon transfer may improve foot drop and thereby decrease disability [9].

Although the concept of surgical release implies cutting fascial layers, El Gharbawy and colleagues [31] have postulated that the fascia surrounding the peroneal (fibular) tunnel actually serves to hold the tunnel open, and therefore care must be taken to preserve this fascia during surgical releases.

Some authors consider the presence of a polyneuropathy (such as that due to diabetes or alcoholism) as a contraindication to surgery [16], though more recent work shows good results in restoring function in diabetics with CPN decompression [45].

Complications

Patients who have severe motor symptoms due to CPN compression are at risk of permanent paralysis. Even though there are reports that surgical neurolysis of compressed CPN can lead to recovery years after the onset of symptoms [6], most authors recommend much earlier intervention if nonoperative measures fail to relieve symptoms.

Summary

Common peroneal/fibular entrapment is one of the most common lower extremity entrapments; it can present in a variety of ways. Diagnostic injections require particular vigilance because of the potential of post-procedure foot drop.

References

Katirji MB, Wilbourn AJ. Common peroneal mononeuropathy: a clinical and electrophysiologic study of 116 lesions. Neurology. 1988;38(11):1723–8.

Donovan A, Rosenberg ZS, Cavalcanti CF. MR imaging of entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. Part 2. The knee, leg, ankle, and foot. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):1001–19.

Van Langenhove M, Pollefliet A, Vanderstraeten G. A retrospective electrodiagnostic evaluation of footdrop in 303 patients. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;29(3):145–52.

Aprile I, Caliandro P, La Torre G, Tonali P, Foschini M, Mondelli M, et al. Multicenter study of peroneal mononeuropathy: clinical, neurophysiologic, and quality of life assessment. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10(3):259–68.

Vieira RL, Rosenberg ZS, Kiprovski K. MRI of the distal biceps femoris muscle: normal anatomy, variants, and association with common peroneal entrapment neuropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(3):549–55.

Humphreys DB, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Patient outcome after common peroneal nerve decompression. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(2):314–8.

Whitmore I. Terminologia anatomica: new terminology for the new anatomist. Anat Rec. 1999;257(2):50–3.

Brief JM, Brief R, Ergas E, Brief LP, Brief AA. Peroneal nerve injury with foot drop complicating ankle sprain – a series of four cases with review of the literature. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2009;67(4):374–7.

Cho D, Saetia K, Lee S, Kline DG, Kim DH. Peroneal nerve injury associated with sports-related knee injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31(5), E11.

Deutsch A, Wyzykowski RJ, Victoroff BN. Evaluation of the anatomy of the common peroneal nerve. Defining nerve-at-risk in arthroscopically assisted lateral meniscus repair. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):10–5.

Yu JK, Yang JS, Kang SH, Cho YJ. Clinical characteristics of peroneal nerve palsy by posture. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;53(5):269–73.

Leach RE, Purnell MB, Saito A. Peroneal nerve entrapment in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(2):287–91.

Haimovici H. Peroneal sensory neuropathy entrapment syndrome. Arch Surg. 1972;105(4):586–90.

Chusid J. Yoga foot drop. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1971;217(6):827–8.

McCrory P, Bell S, Bradshaw C. Nerve entrapments of the lower leg, ankle and foot in sport. Sports Med. 2002;32(6):371–91.

Fabre T, Piton C, Andre D, Lasseur E, Durandeau A. Peroneal nerve entrapment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(1):47–53.

Spinner RJ, Amrami KK. Superficial peroneal intraneural ganglion cyst originating from the inferior tibiofibular joint: the latest chapter in the book. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(6):575–8.

Jang SH, Lee H, Han SH. Common peroneal nerve compression by a popliteal venous aneurysm. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(11):947–50.

Cruz-Martinez A, Arpa J, Palau F. Peroneal neuropathy after weight loss. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2000;5(2):101–5.

Marciniak C. Fibular (peroneal) neuropathy: electrodiagnostic features and clinical correlates. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013;24(1):121–37.

Anderson AW, LaPrade RF. Common peroneal nerve neuropraxia after arthroscopic inside-out lateral meniscus repair. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(1):27–9.

Baima J, Krivickas L. Evaluation and treatment of peroneal neuropathy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(2):147–53.

Sedel L, Nizard RS. Nerve grafting for traction injuries of the common peroneal nerve. A report of 17 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1993;75(5):772–4.

Kashuk K. Proximal peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes in the lower extremity. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1977;67(8):529–44.

Dong Q, Jacobson JA, Jamadar DA, Gandikota G, Brandon C, Morag Y, et al. Entrapment neuropathies in the upper and lower limbs: anatomy and MRI features. Radiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:230679.

Vasudevan JM, Freedman MK, Beredjiklian PK, Deluca PF, Nazarian LN. Common peroneal entrapment neuropathy secondary to a popliteal lipoma: ultrasound superior to magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis. PM R. 2011;3(3):274–9.

Ryan W, Mahony N, Delaney M, O’Brien M, Murray P. Relationship of the common peroneal nerve and its branches to the head and neck of the fibula. Clin Anat. 2003;16(6):501–5.

Aigner F, Longato S, Gardetto A, Deibl M, Fritsch H, Piza-Katzer H. Anatomic survey of the common fibular nerve and its branching pattern with regard to the intermuscular septa of the leg. Clin Anat. 2004;17(6):503–12.

Sumalatha S, DS AS, Yadav JS, Mittal SK, Singh A, Kotian SR. An unorthodox innervation of the gluteus maximus muscle and other associated variations: a case report. Aust Med J. 2014;7(10):419–22.

Gloobe H, Chain D. Fibular fibrous arch. Anatomical considerations in fibular tunnel syndrome. Acta Anat. 1973;85(1):84–7.

El Gharbawy RM, Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis JE. Protective mechanisms of the common fibular nerve in and around the fibular tunnel: a new concept. Clin Anat. 2009;22(6):738–46.

Boon AJ, Dib MY. Peripheral nerve entrapment and compartment syndromes of the lower leg. In: Akuthola V, Herring SA, editors. Nerve and vascular injuries in sports medicine. Philadelphia: Springer; 2009. p. 139–59.

Zipple JT, Hammer RL, Loubert PV. Treatment of fabella syndrome with manual therapy: a case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(1):33–9.

Rousseau E. The anterior recurrent peroneal nerve entrapment syndrome: a patellar tendinopathy differential diagnosis case report. Man Ther. 2013;18(6):611–4.

Mont MA, Dellon AL, Chen F, Hungerford MW, Krackow KA, Hungerford DS. The operative treatment of peroneal nerve palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(6):863–9.

Ang CL, Foo LS. Multiple locations of nerve compression: an unusual cause of persistent lower limb paresthesia. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(6):763–7.

Sidey JD. Weak ankles. A study of common peroneal entrapment neuropathy. Br Med J. 1969;3(5671):623–6.

Kopell HP, Thompson WA. Peripheral Entrapment Neuropathies. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1976.

Flanigan RM, DiGiovanni BF. Peripheral nerve entrapments of the lower leg, ankle, and foot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2011;16(2):255–74.

Derr JJ, Micklesen PJ, Robinson LR. Predicting recovery after fibular nerve injury: which electrodiagnostic features are most useful? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(7):547–53.

Maalla R, Youssef M, Ben Lassoued N, Sebai MA, Essadam H. Peroneal nerve entrapment at the fibular head: outcomes of neurolysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(6):719–22.

Reife MD, Coulis CM. Peroneal neuropathy misdiagnosed as L5 radiculopathy: a case report. Chiropr Man Ther. 2013;21(1):12.

Ting PH, Antonakakis JG, Scalzo DC. Ultrasound-guided common peroneal nerve block at the level of the fibular head. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24(2):145–7.

Lynch P, McJunkin T, Barrett S, Maloney J. A new surgical approach to peripheral nerve stimulation of the deep and superficial peroneal nerves for peroneal nerve pain (poster presentation). AAPM annual meeting. Washington, DC; 2011.

Aszmann OC, Kress KM, Dellon AL. Results of decompression of peripheral nerves in diabetics: a prospective, blinded study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(4):816–22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Physical exam of the common peroneal nerve (MOV 20056 kb)

Landmark-guided injection of the common peroneal nerve (MOV 26151 kb)

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murinova, N., Chiu, S.C., Krashin, D., Karl, H.W. (2016). Common Peroneal Nerve Entrapment. In: Trescot, A.M. (eds) Peripheral Nerve Entrapments. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27482-9_67

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27482-9_67

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-27480-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-27482-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)