Abstract

In recent decades, corporate communication has undergone significant changes in terms of channel, content and receivers. To be accountable, companies are called upon to satisfy a plurality of stakeholders who are increasingly interested in non-financial information. In addition, the type and scope of information can significantly influence the competitive advantage of the company and especially, its credibility and reputation. Today, companies are required to engage in corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to give response to the call for action from their stakeholders and society. However, some companies engage in CSR initiatives with the aim of only achieving or increasing their level of legitimacy. When companies offer misleading communication and then try to influence the perceptions of their stakeholders, they incur the phenomenon known in literature as “greenwashing”. Thus, the aim of this work is to analyse the phenomenon of greenwashing, tracing its evolution in the extant literature. Greenwashing will then be analysed through the lens of the legitimacy theory and starting from Habermas’s communication theory to define and broaden the relationships between the concepts of disclosure, credibility, legitimacy, perception and greenwashing.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate social responsibility

- Disclosure

- Greenwashing

- Legitimacy theory

- Habermas’s communication theory

- Communication credibility

- Perception

1 Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implies a willingness to respond to the requests and expectations of various stakeholders who each have a different nature, as well as characteristics (Freeman 1984; Donaldson and Preston 1995; Mitchell et al. 1997; Garriga and Melé 2004; Werther and Chandler 2006). The relation between society and business has been theorized for the first time by Bowen (1953), Carroll (1998), Wartick and Cochran (1985); however, in the 1960s, interest in CSR began to emerge when the idea that firms, though primarily economic institutions, also exert significant influence within society (Roberts 1992). Furthermore, in the twenty-first century, the number of studies on CSR has increased significantly (Lyon and Montgomery 2015; Wagner et al. 2009). Some studies (e.g. Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Carroll and Shabana 2010) analyse CSR literature in general, while others focus on CSR theories (e.g. Lee 2008; Frynas and Yamahaki 2016). From this perspective, the contributions of Garriga and Melé (2004) tried to classify the main CSR theories and related approaches. In particular, the authors identified four groups of theories (Garriga and Melé 2004: 52–53), including:

-

Instrumental Theories: Because the firm is an instrument for wealth creation, any supposed social activity is accepted if, and only if, it is consistent with wealth creation;

-

Political Theories: The company accepts social duties and rights or participates in certain social cooperation because of its responsibility in the “political arena” associated with its social power, specifically in its relationship with society;

-

Integrative Theories: Firms need to integrate social demands into their business because they depend on society for their existence, continuity and growth;

-

Ethical Theories: The relationship between the company and society implies ethical values; in this sense, these firms ought to accept social responsibilities as ethical obligations.

In this final perspective, CSR needs to be considered by firms in their strategy and thus, can be a real source of social progress. Firms as social actors play a primary role in ensuring that present and future generations apply resources, expertise and insights into activities that benefit society (Porter and Kramer 2006).

Nevertheless, there has been a worrying increase in the amount of misleading information produced by companies, including information on environmental and social aspects (Lydenberg 2002). In different quarters, particularly among social and environmental activists, concerns are being increasingly raised about corporate deception, which is sometimes imbedded in rhetoric (McQuarrie and Mick 2003). There is increasing the apprehension that some companies may be creatively managing their reputations with their stakeholders (customers, financial community, regulators, society, etc.) to hide faults and problems, improve their reputation or appear more competitive.

In the existing literature, interest in greenwashing has increased, although there is currently no single accepted definition of the term. Different definitions and perspectives have been put forward and adopted (Seele and Gatti 2017; Wilson et al. 2010), but in general, it is recognised as a misleading communication practice concerning environmental issues (Torelli et al. 2020). Numerous studies focus on different types of corporate engagements in greenwashing (Du 2015; Testa et al. 2018; Vries et al 2015) and have found that one of the most frequent reasons is to attain legitimacy (Walker and Wan 2012). This is because legitimacy leads to stronger relationships, and thus, companies try to achieve or preserve it through disclosure and may pursue strategies to influence stakeholder perception. Moreover, numerous studies find that information about the social and environmental responsibility of a company influences stakeholders (customers, employees, investors, communities, etc.), which means that legitimacy is a critical feature (Walker and Wan 2012). The only other way to legitimisation for a firm is to use credibility (Coombs 1992; Seele and Lock 2015), which exists when stakeholders’ expectations coincide with what companies actually do (Lock and Seele 2016; Sethi 1975).

The aim of this study is twofold. Firstly, it aims to review the different definitions and perspectives used in management literature to study and analyse greenwashing. Secondly, it traces the relationship between the concepts of communication, credibility, legitimacy, greenwashing and perceptions through the lens of legitimacy theory, starting from Habermas’s communicative action theory (1984).

The study is comprised of three main sections. The first focuses on the definition of greenwashing and the different perspectives in which it is analysed in current literature. The second describes the relationship between greenwashing and four key variables (communication, credibility, legitimacy and perceptions). In the final section, some conclusions are drawn.

2 Misleading Corporate Communication: Towards a Definition of Greenwashing

Corporate social responsibility represents a voluntary approach taken by an enterprise to meet stakeholder expectations, taking into account their different features (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1984; Mitchell et al. 1997; Werther and Chandler 2006). Engaging in corporate social responsibility initiatives is the main corporate response by stakeholders and society in general to the call for action.

CSR initiatives are extremely varied. They can be taken at different levels of corporate organisation and strategy, and can be voluntary or in response to an obligation, short, medium or long term, and targeted at different goals (profit, environmental protection, ethical, social behaviour). Organisations engage in certain CSR initiatives (e.g. environmental) to attain corporate legitimacy (Walker and Wan 2012; Seele and Gatti 2017), but in reality, the engagement may in fact be purely symbolic. Simply giving the impression of being socially responsible can be easier, cheaper and more flexible for companies, and at first, may bring the same benefits as true commitment (Walker and Wan 2012). However, when companies act through misleading communication only at a symbolic level with the aim of strategically influencing stakeholder perceptions, greenwashing acts in pragmatic legitimacy context (Seele and Gatti 2017).

The debate on greenwashing first appeared in the 1960s because of the growth of environmentalism. Environmentalists termed corporate greenwashing actions and strategies “eco-pornography”. However, the first to coin the term “greenwashing” was biologist and environmental activist Jay Westerveld, who, in 1986, interpreted an invitation about towel use in his hotel roomFootnote 1 as the hotel trying to save money rather than protecting the environment by reducing water consumption.

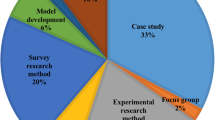

Academic studies on greenwashing started only in the mid-1990s, when Greer and Bruno (1996) discussed it in their book on environmental marketing (Laufer 2003). Because it has many impacts and practical applications in the real world and because it offers important spaces for research, lying at the intersections of various academic disciplines, greenwashing has become an increasingly significant topic in academic literature over the last decade. From 1995 to 2014, a total of 105 full-length peer-reviewed articles in academic journal articles focused on greenwashing from various perspectives. That number increased rapidly after 2007, particularly in 2011 (Lyon and Montgomery 2015).

Some studies focus on the impact on financial performance of both substantial and symbolic actions (Du 2015; Walker and Wan 2012). These studies discuss not only greenwashing but also the consequences of true positive environmental actions and performance properly advertised and disclosed. Walker and Wan (2012) call this “green-highlighting”. These studies prove the negative effect of greenwashing on financial performance when it is discovered, but they do not agree on the impact of good environmental performance.

Other works analyse the importance of motivation (economic or true environmental motivation) in an investment in environmental performance (Vries et al. 2015). These authors find that there is a lower perception of greenwashing when there is an economic incentive for environmental investment. However, suspicion of strategic behaviours and scepticism can mediate this relationship.

The concept of greenwashing is also studied from a marketing perspective:

-

Nyilasy et al. (2014) focused on the impact on brand attitude and the purchase intentions of green claims and true positive environmental performance;

-

Guo et al. (2017) analysed the effect of decoupling “green promises” from brand trust, brand legitimacy and brand loyalty;

-

Wilson et al. (2010) discussed how consumer perception and attitude can change towards a company, focussing on recent environmental scandals affecting actively socially responsible companies.

Some researchers focus on the impacts of cultural beliefs concerning competition and individual responsibility on corporate social actions (Roulet and Touboul 2015). Others describe the effects of different types of corporate leadership (e.g. ethical or authoritative) and on corporate conduct and actions (Blome et al. 2017), finding that authoritative leadership is associated with a higher number of cases of greenwashing.

Two recent studies investigate the concept of greenwashing, looking at the process of accusation after the discovery of misleading communication (Seele and Gatti 2017) and the new aspects of illegal/irresponsible actions in greenwashing based on the detailed case study of a high-profile emission scandal (Siano et al. 2017).

Through the lens of signalling and institutional theory, Berrone et al. (2017) analyse the impact of environmental actions as signals on environmental legitimacy, exploring the case of positive signals of firm’s environmental stance and poor environmental performance (greenwashing). Research findings highlight the positive impact on the corporate legitimacy of some types of environmental actions (e.g. patents, pay policies and trademarks), but also on the fact that pay policies and trademarks can only increase environmental legitimacy when companies have strong credibility. Berrone et al. (2017) also stress the role of environmental NGOs, which have a negative moderating effect on environmental performance impact and on corporate legitimacy.

Some studies analyse how and why disclosure on activities in environmental measures provided by firms can affect stakeholder perception of corporate greenwashing. In particular, Vries et al. (2015) found that people often see company disclosure about environmental issues and performances as communicative fashion rather than being truthful. They emphasise that the perception of corporate greenwashing is highly influenced by the typology of communication about investments and commitments towards environmental responsibility. Other studies (Forehand and Grier 2003; Vries et al. 2015; Yoon et al. 2006) observe that people may suspect of the truthfulness of claims and hypothesise underhanded purposes. Furthermore, some researchers show (Cho et al. 2009; Milne and Patten 2002) that in some context transparent environmental communications have successfully offset public perception of the deteriorating effects of liability exposures. This phenomenon frequently occurs when companies take purely symbolic actions in signalling to stakeholders their values and refer to the environment and green issues in a misleading way, choosing to engage in “green talk” without a “green walk” (Ramus and Montiel 2005; Torelli et al 2020).

Nowadays, the attention towards corporate environmental responsibility and performances is very high, and environmental scandals are highly regarded topic (Siano et al. 2017). Some studies have focused on the effects of stakeholder discovery of greenwashing (Torelli et al. 2020); other have highlighted the effects on financial performance (Du 2015; Walker and Wan 2012), while others have examined the impact on trust and loyalty (Guo et al. 2017).

Some studies (Cho et al. 2006, 2009; Patten 2002) have analysed the impact of industry on stakeholder perceptions: in the case of firms operating in Environmentally Sensitive Industries (ESI), firms with poor environmental performance may engage in misleading environmental communication to gain legitimacy, reputation, trust and reduce the suspicion of environmentally despicable behaviour

Several studies have analysed the relationship between social accountability transparency and audits. From this perspective, some authors consider social auditing as a way to promote transparency and accountability (e.g. Zadek and Raynard 1995; Gonella et al. 1998); furthermore, the study of Owen et al. (2000) was very interesting, as this article aims to identify fundamental values for conventional social audits and to analyse the developments that underpin “new” social audits (p. 82).

Up to this point, the literature has noted different perspectives of greenwashing studies. Further studies can be classified into two levels: firm-level and product-level.

At the firm-level, greenwashing is related to a distorted disclosure of environmental topics concerning the whole firm. At the firm-level, greenwashing is a sizeable phenomenon associated with distortive and selective disclosure, whereby companies divulge good environmental strategies and actions and conceal negative ones. This is done to create a positive but misleading impression of the firm’s real environmental performance (Lyon and Maxwell 2011). Nowadays, firm-level greenwashing is significant because of increasing stakeholder demand for high levels of accountability and transparency (Bromley and Powell 2012) and because of the emergence and growing diffusion of “environmental greenwashing” frequently used by organised crime, eco-mafia and eco-criminals (Massari and Monzini 2004; Rege and Lavorgna 2017). At the firm-level, greenwashing can be regarded as a specific strategy that companies adopt to engage in symbolic communications of environmental issues without translating them into actions (Walker and Wan 2012). It can be associated with symbolic actions, referring to plans, or with substantive actions, referring to what a firm is currently doing. At the product-level, greenwashing is associated with an explicit marketing strategy, in which firms publicise elusive environmental benefits of a specific product or service to customers (Delmas and Burbano 2011; TerraChoice 2009).

To conclude this literature review, note that there is no single accepted definition of greenwashing. Delmas and Burbano (2011) define greenwashing as “poor environmental performance and positive communication about environmental performance”. Lyon and Montgomery (2015), in their review of the cross-disciplinary literature on greenwashing, state, “The word greenwash is used to cover any communication that misleads people into adopting overly positive beliefs about an organization’s environmental performance, practices, or products”. Other researchers have focused on the concept of accusation to define greenwashing. Seele and Gatti (2017) say that, “Greenwashing is a co-creation of an external accusation toward an organization with regard to presenting a misleading green message”. Walker and Wan (2012) focused on the difference between symbolic and substantive actions, and define greenwashing as “a strategy that companies adopt to engage in symbolic communications of environmental issues without substantially addressing them in actions”. Many other definitions have recently been put forward by NGOs (e.g. Greenpeace) and the mainstream media. In particular, TerraChoice Group Inc. (2009) defined greenwashing as “the act of misleading consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company (firm-level greenwashing) or the environmental benefits of a product or service (product-level greenwashing)”. This definition covers only one category of stakeholders (consumers) interested in greenwashing and only two levels of greenwashing (firm and product levels).

In conclusion, note that because the concept is vast, complex and interdisciplinary, a clear definition of the concept of greenwashing would probably be of limited usefulness.

3 The Search for Legitimacy: The Role of Greenwashing, Credibility and Perception

Greenwashing is rooted in the firms’ need for legitimation, in the essential perception that the actions of a firm are desirable, proper or appropriate within a socially constructed system of norms, values and beliefs (Suchman 1995; Torelli et al. 2020). Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) and Lindblom (1994) highlighted that companies that intend to maintain or increase their legitimacy have a greater propensity to implement communication practices related to the concept of greenwashing influencing stakeholders’ perception. Alniacik et al. (2011) have found that purchase, employment, and investment intentions of various stakeholders are significantly influenced by the communication of information, whether negative or positive, regarding social and environmental responsibility. Legitimacy represents a key issue for companies because it can lead to significant improvement in, job applicants, access to resources, market reputation and financial performance (Aldrich and Fiol 1994; Babiak and Trendafilova 2011; DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Deephouse 1999; Oliver 1991; Walker and Wan 2012).

Thus, recent studies (Cho et al. 2009; Forehand and Grier 2003; Milne and Patten 2002; Patten and Crampton 2003; Vries et al. 2015; Yoon et al. 2006) have analysed the importance of affecting stakeholder perception of corporate communication, social and environmental responsibility and corporate greenwashing.

These studies reflect greater attention to CSR and CSR disclosure by academics and corporate management, while CSR reports are acknowledged to be the most effective CSR communication tool (Hooghiemstra 2000); however, perceptions of credibility remain a poorly understood issue. As such, this section proposes a basic theoretical model of the relationships between the concepts of corporate communication, credibility, legitimacy, perception and greenwashing.

To obtain legitimacy, corporate communication and disclosure requires a sufficient level of credibility (Coombs 1992; Seele and Lock 2015). However, there is frequently a credibility perception gap (Dando and Swift 2003): a discrepancy between what stakeholders expect and what companies do, or rather what they perceive companies do (Sethi 1975). Thus, credibility has a key role as a basis of trust and in particular, of legitimacy (Coombs 1992). The same item of CSR communication can be considered believable at first sight in the eyes of the company and its managers, but at the same time, can be perceived as not credible (Lock and Seele 2016; Seele 2016), as a sort of fashionable distraction, or an attempt at greenwashing by a stakeholder.

Habermas’s communicative action theory (1984) is very useful in analysing corporate communication. Furthermore, Habermas considers social action based on two main components: strategic action and communicative action. Strategic action is regarded as an action oriented to success and achieved by influencing the actions of other rational actors, while communicative action is oriented towards reaching mutual understanding. Through communicative action, the actors cooperate to define the context of their interaction with the aim of pursuing their own objectives. Habermas (1984) argues that communication is a process based on a set of norms, or validity claims, accepted by all communicators to develop and maintain a correct and ideal communication process and to construct a common understanding. The main norms in a communication process are:

-

Understandability: Ensures that the statement is clearly understandable by the actors;

-

Truthful: The communicator provides a true and correct message. He/She does not deliberately give misleading information;

-

Sincere expression: The communicator is truthful and believable. This norm is connected to the subjective beliefs underlying the statements;

-

Appropriateness (social order): Communication is related to the social order that each actor is part of. The actor takes a position with respect to the normative or legitimate social order (Fig. 1).

A critical role in corporate communications is played by stakeholder perception (for details, see Wagner et al. 2009; Lock and Seele 2017). If it is true that to obtain legitimacy, a communication must have credibility (Lock and Seele 2017; Seele and Lock 2015; Lock and Seele 2016) and be built on the presence of all four of Habermas’s principles, it is equally important to fully evaluate and consider the role of perception (in this stakeholder context) as a moderator or amplifier both in achieving credibility and in obtaining legitimacy. Thus, the concept of credibility can be considered as a multidimensional perception construct (Jackob 2008). Likewise, the concept of legitimacy can be considered to be based on, or to be, a perception construct. Actually, the legitimacy of an organisation is considered as its perceived conformity with norms, traditions and social rules (Suchman 1995).

If we include in the model the concept of greenwashing as a misleading environmental communication based on either negative or partially positive environmental performance (Walker and Wan 2012; Delmas and Burbano 2011; Lyon and Montgomery 2015), the role of stakeholder perception in the transition from communication to legitimacy becomes decisive. Starting from Habermas’s communication theory, we assume that greenwashing is the result of a strategic action, which, through the communication process, aims to give stakeholders a misleading perception of environmental corporate performance to obtain legitimacy. Therefore, legitimacy is achieved if stakeholders perceive that the message communicated by the company is credible. Greenwashing is thus generated when there is a gap between the reality and the perception induced in the stakeholder by corporate disclosure; in other words, when the norms of truthful and sincerity are violated, the message communicated expressly contains misleading elements.

Figure 2 shows the main relationships between the concepts of communication, credibility, legitimacy, greenwashing and perception, while certain key aspects are highlighted. In a corporate disclosure, the first validity claim proposed by Habermas (1984), understandability, can be considered a precondition (Zinkin 1998), or a necessary condition for the proper functioning of communication between sender and receiver, which in this case, is the company and stakeholders. Without understandability, there is no basis for communication (Lock and Seele 2016). Thus, for company disclosure to satisfy Habermas’s conditions of appropriateness and sincerity, it needs to be reliable, responsive and exhaustive. The concept of truth, on the other hand, is very difficult to measure and is present only in real life; in other words, it is what stakeholders use to evaluate the corporate communication received.

Misleading communication, such as greenwashing, can be an attempt by the sender to bypass the respect for the conditions set out by Habermas for correct communication, which leads to credibility (Connelly et al. 2011; Berrone et al. 2017). Through the phenomenon of greenwashing, the company tries to communicate something that does not actually exist, or exists in part, or that exists but not as it is communicated (Walker and Wan 2012; Ramus and Montiel 2005). The communication is therefore artificial, not sincere, not true and not appropriate, but in some cases, it can still be considered as credible.

The concept of perception comes into play at different times in the act of communication. In the transition from Habermas’s validity claims to the concept of credible communication, the perception by the receiver (stakeholder) plays a key role (Cho et al. 2009; Vries et al. 2015; Wilson et al. 2010). Apart from the objective truth of what communication deals with, the other two validity claims are subject to a subjective judgement, for example the perception of the individual receiver (Suchman 1995; Seele and Gatti 2017). Therefore, the same communication can be taken as appropriate and sincere by one receiver and not credible by another.

As Jackob (2008) pointed out, credibility is the outcome of a subjective evaluation process carried out by the receiver on the message and, above all, on its content, so that the result of this process can differ each time. Even if a company tries to go beyond the steps of a correct communicative process (Habermas 1984) and uses greenwashing (e.g. Berrone et al. 2017), the message still has to be perceived by the receiver who receives the message and evaluates its credibility (Lock and Seele 2017). Here, the risk for the company of gaining negative evaluation by stakeholders on communication is likely to be greater because in not meeting the four validity claims, it is based not on facts and appropriateness but on artefact, fashion and impression management (Mahoney et al. 2013; Neu et al. 1998; Seele and Gatti 2017). Whether it is sincere and credible communication or deceptive communication that has obtained credibility from the receiver, perception still has a role in the transition from credibility to legitimacy (Jackob 2008). However, this is not immediately obvious. Furthermore, the transition cannot be attributed only to the presence/absence of the perception of credibility, but needs to be considered from the point of view of perception. This is particularly true given that stakeholders often consider CSR communication not credible but only a strategic tool from the start (Elving 2013; Illia et al. 2013; Milne and Gray 2013). A communication evaluated as credible, whether it is objectively credible or not, passes through further consideration, evaluation and discernment by the receiver in obtaining legitimacy. Here, once again, perception has an important role. Moreover, even the concept of legitimacy should not be considered as objective and as a certain concept, but as a construct of perception (Suchman 1995). The issue of communication credibility is accentuated by the fact that stakeholders often see a lack of credibility in CSR communication (Coombs and Holladay 2013) and by general cynicism towards CSR communication (Illia et al. 2013).

When situations occur in which corporate communication is not credible (credibility gap) or, although considered credible, fails to reach the concept of legitimacy (legitimacy gap), there is often inconsistency between what the company says and what the company does, or seems to do (Basu and Palazzo 2008). Thus, it is important to assess the role played by perception among stakeholders. In these cases, the role of the moderator/amplifier of perception is crucial. As such, the case of greenwashing is very interesting and complex because, in the case of misleading communication, the sender will base the entire communication on the exploitation of perception (Seele and Gatti 2017; Suchman 1995) in his/her role as an amplifier of credibility. If this role of perception does not work as expected, the construct of communication fails, because the four validity claims are lacking as supporting pillars (Habermas 1984; Lock and Seele 2017). Through misleading stakeholders, a company tries to meet the stakeholder requirement for the legitimacy of the firm in society, but will not respond truthfully or completely (Claasen and Roloff 2012). Neither will it succeed in filling the credibility gap that is only deepened by CSR communication and by corporate hypocrisy (Dando and Swift 2003; Wagner et al. 2009).

CSR perception has an important role in affecting trust, reputation, firm image, propensity of consumers/investors and financial performance (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006). Vague or empty communications, in other words communication without real performance, generate stakeholder perception of corporate hypocrisy (Wagner et al. 2009). Greenwashing is a perfect example of this process. CSR communication and CSR perception are affected negatively by inconsistency. Perception of corporate hypocrisy, i.e. the difference between a statement and the real action, appears to be stronger when companies focus first on the statement by publishing it and only later, the real action. This proactive CSR strategy (Wagner et al. 2009) is more damaging than a reactive CSR strategy, where actions are made before statements appear. Greenwashing could be considered as an extreme case of corporate hypocrisy because misleading stakeholders here is crucial (see Seele and Gatti 2017 and Delmas and Burbano 2011). In the intention of disseminating positive CSR communication, a company attempting greenwashing focuses exclusively (or almost exclusively) on issuing its statement, as well as on perception and not (or not exclusively) on performance (Delmas and Burbano 2011; Lyon and Montgomery 2015). This is the problem of “talking the talk without walking the walk” (Ramus and Montiel 2005).

4 Conclusions

After having analysed and classified different definitions of greenwashing in extant literature, this study focused on the relationships between greenwashing and legitimacy. In literature, it is commonly recognised that credibility (Dando and Swift 2003) has become a critical feature for companies to gain trust and legitimacy. Nowadays, because of the increasing expectations of stakeholders, there is a high risk that corporate communication will be considered unreliable, creating a real gap in trust and legitimacy.

Starting from these assumptions and based on previous research (Habermas 1984; Lock and Seele 2017; Patten and Crampton 2003; Cho et al. 2009; Vries et al. 2015), this work has analysed the role of information disclosure in gaining legitimation and improving stakeholder perceptions.

Misleading communications—greenwashing—can be used by companies to meet stakeholder expectations by avoiding the correct rules of communication, with the aim of communicating something that is not really true or only partially true (Walker and Wan 2012; Ramus and Montiel 2005). Thus, stakeholder perception plays a decisive role in the process because the same message can be considered appropriate and sincere by one receiver, but not credible by another. Because credibility derives from a subjective evaluation process (Jackob 2008), companies using greenwashing risk negative evaluation by stakeholders, as well as losing their legitimacy. This kind of risk is particularly real because stakeholders often consider CSR communication as a strategic tool, which is not in itself wholly credible. When there is a credibility gap between companies and stakeholders, there is a problem of inconsistency and perception, which comes to play a crucial role. If perception does not work as expected, the whole construct of communication fails. By adopting greenwashing practices, companies aim to disseminate positive CSR communication by “talking the talk without walking the walk” (Ramus and Montiel 2005).

A critical role in the communication process is played by the perception of credibility generated by stakeholders. The perception of credibility seems to be affected by four fundamental conditions: comprehensibility, reliability, responsiveness and exhaustiveness. Although it is complex and difficult to identify possible solutions to the problems of misleading communication, which are often rooted in the culture of corporate management, we can consider a first attempt to limit these practices in the adoption of an in-depth process of external verification of data and information reported by companies (Owen et al. 2000).

The main limitation of this study is the lack of practical application and empirical verification of the theoretical concepts developed and proposed. Moreover, the work does not explore possible solutions or methods to limit situations of misleading communication.

Future empirical research will be useful to develop methods of measuring stakeholder perception of disclosure and its credibility. It would also be interesting to investigate the level of credibility of corporate environmental disclosure in different contexts and industries.

Notes

- 1.

“Save Our Planet: Every day, millions of gallons of water are used to wash towels that have only been used once. You make the choice: A towel on the rack means, ‘I will use again.’ A towel on the floor means, ‘Please replace.’ Thank you for helping us conserve the Earth’s vital resources”.

Literature

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19, 645–670.

Alniacik, U., Alniacik, E., & Genc, N. (2011). How corporate social responsibility information influences stakeholders’ intentions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(4), 234–245.

Babiak, K., & Trendafilova, S. (2011). CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18, 11–24.

Basu, K., & Palazzo, G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 122–136.

Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., & Gelabert, L. (2017). Does greenwashing pay off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions and environmental legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 363–379.

Blome, C., Foerstl, K., & Schleper, M. C. (2017). Antecedents of green supplier championing and greenwashing: An empirical study on leadership and ethical incentives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 152, 339–350.

Bowen, H. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessmen. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Bromley, P., & Powell, W. W. (2012). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 483–530.

Carroll, A. B. (1998). The four faces of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review, 100(1), 1–7.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12, 85–105.

Cho, C. H., Patten, D. M., & Roberts, R. W. (2006). Corporate political strategy: An examination of the relation between political expenditures, environmental performance, and environmental disclosure. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(2), 139–154.

Cho, C. H., Phillips, J. R., Hageman, A. M., & Patten, D. M. (2009). Media richness, user trust, and perceptions of corporate social responsibility: An experimental investigation of visual web site disclosures. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22(6), 933–952.

Claasen, C., & Roloff, J. (2012). The link between responsibility and legitimacy: The case of De Beers in Namibia. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 379–398.

Coombs, W. T. (1992). The failure of the task force on food assistance: A case study of the role of legitimacy in issue management. Journal of Public Relations Research, 4, 101–122.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2013). The pseudo-panopticon: The illusion created by CSR-related transparency and the internet. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 18(2), 212–227.

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67.

Dando, N., & Swift, T. (2003). Transparency and assurance minding the credibility gap. Journal of Business Ethics, 44, 195–200.

Deephouse, D. L. (1999). To be different, or to be the same? It’s a question (and theory) of strategic balance. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 147–166.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pacific Sociological Review, 18, 122–136.

Du, X. (2015). How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 547–574.

Elving, W. J. (2013). Scepticism and corporate social responsibility communications: The influence of fit and reputation. Journal of Marketing Communications, 19(4), 277–292.

Forehand, M. R., & Grier, S. (2003). When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 349–356.

Freeman, E. R. (1984). Strategic Management: A stakeholder approach. Marshfield (Mass): Pitman.

Frynas, J. G., & Yamahaki, C. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25, 258–285.

Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1–2), 51–71.

Gonella, C., Pilling, A., & Zadek, S. (1998). Making values count: Contemporary experience in social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting. London: Association of Chartered Certified Accountants.

Greer, J., & Bruno, K. (1996). Greenwash: The reality behind corporate environmentalism. Reality behind corporate environmentalism. New York: Apex Press.

Guo, R., Tao, L., Li, C., & Wang, T. (2017). A path analysis of greenwashing in a trust crisis among Chinese energy companies: The role of brand legitimacy and brand loyalty. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 523–536.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Boston: Beacon Press.

Hooghiemstra, R. (2000). Corporate communication and impression management—New perspectives why companies engage in corporate social reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 27, 55–68.

Illia, L., Zyglidopoulos, S. C., Romenti, S., Rodriguez-Canovas, B., & del Valle Brena, A. G. (2013). Communicating corporate social responsibility to a cynical public. MIT Sloan Management Review, 54(3), 15–18.

Jackob, N. (2008). Credibility effects. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), International encyclopedia of communication (pp. 1044–1047). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Laufer, W. S. (2003). Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 253–261.

Lee, M.-D. P. (2008). A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10, 53–73.

Lindblom, C. K. (1994). The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. In Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York.

Lock, I., & Seele, P. (2016). The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 122, 186–200.

Lock, I., & Seele, P. (2017). Measuring credibility perceptions in CSR communication: A scale development to test readers’ perceived credibility of CSR reports. Management Communication Quarterly, 31(4), 584–613.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(October), 1–18.

Lydenberg, S. D. (2002). Envisioning socially responsible investing. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 7, 57–77.

Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2011). Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 20(1), 3–41.

Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and end of greenwash. Organization and Environment, 28(2), 223–249.

Mahoney, L. S., Thorne, L., Cecil, L., & LaGore, W. (2013). A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signalling or greenwashing? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(4/5), 350–359.

Massari, M., & Monzini, P. (2004). Dirty businesses in Italy: A case-study of illegal trafficking in hazardous waste. Global Crime, 6(3–4), 285–304.

McQuarrie, E. F., & Mick, D. G. (2003). The contribution of semiotic and rhetorical perspectives to the explanation of visual persuasion in advertising. In L. G. Scott & R. Batra (Eds.), Persuasive imagery: A consumer response perspective (pp. 191–221). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). W(h)ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118, 13–29.

Milne, M. J., & Patten, D. M. (2002). Securing organizational legitimacy: An experimental decision case examining the impact of environmental disclosures. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 372–405.

Neu, D., Warsame, H., & Pedwell, K. (1998). Managing public impressions: Environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3), 265–282.

Nyilasy, G., Gangadharbatla, H., & Paladino, A. (2014). Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 693–707.

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179.

Owen, D., Swift, T. S., Humphrey, C., & Bowerman, M. (2000). The new social audits: Accountability, managerial capture or the agenda of social champions? The European Accounting Review, 9(1), 81–98.

Patten, D. M. (2002). The relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27(8), 763–773.

Patten, D. M., & Crampton, W. (2003). Legitimacy and the internet: An examination of corporate web page environmental disclosures. Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management, 2, 31–57.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Ramus, C. A., & Montiel, I. (2005). When are corporate environmental policies a form of greenwashing? Business and Society, 44(4), 377–414.

Rege, A., & Lavorgna, A. (2017). Organization, operations, and success of environmental organized crime in Italy and India: A comparative analysis. European Journal of Criminology, 14(2), 160–182.

Roberts, R. W. (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(6), 595–612.

Roulet, T., & Touboul, S. (2015). The intentions with which the road is paved: Attitudes to liberalism as determinants of greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(2), 305–320.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2011). The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 899–931.

Seele, P. (2016). Digitally unified reporting: How XBRL-based real-time transparency helps in combining integrated sustainability reporting and performance control. Journal of Cleaner Production, 136, 65–77.

Seele, P., & Gatti, L. (2017). Greenwashing revisited: In search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(2), 239–252. (Wiley).

Seele, P., & Lock, I. (2015). Instrumental and/or deliberative? A typology of CSR communication tools. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(2), 401–414.

Sethi, S. P. (1975). Dimensions of corporate social performance: An analytical framework. California Management Review, 17(3), 58–64.

Siano, A., Vollero, A., Conte, F., & Amabile, S. (2017). “More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. Journal of Business Research, 71, 27–37.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

TerraChoice. (2009). The seven sins of greenwashing. Available at http://sinsofgreenwashing.com/findings/greenwashing-report-2009/index.html. Accessed 28 March 2018.

Testa, F., Boiral, O., & Iraldo, F. (2018). Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? Journal of Business Ethics, 147(2), 287–307.

Torelli, R., Balluchi, F., & Lazzini, A. (2020). Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29, 407–421.

Vries, G., Terwel, B. W., Ellemers, N., & Daamen, D. D. L. (2015). Sustainability or profitability? How communicated motives for environmental policy affect public perceptions of corporate greenwashing. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(3), 142–154.

Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., & Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73, 77–91.

Walker, K., & Wan, F. (2012). The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 227–242.

Wartick, S. L., & Cochran, P. L. (1985). The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 758–769.

Werther, W. B., & Chandler, D. (2006). Strategic corporate social responsibility. Stakeholder in a global environment. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Wilson, A., Robinson, S., & Darke, P. (2010). When does greenwashing work? Consumer perceptions of corporate parent and corporate societal marketing firm affiliation. Advances in Consumer Research, 37, 931–932.

Yoon, Y., Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Schwarz, N. (2006). The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16, 377–390.

Zadek, S., & Raynard, P. (1995). Accounting works: A comparative review of contemporary approaches to social and ethical accounting. Accounting Forum, 19, 164–175.

Zinkin, M. (1998). Habermas on intelligibility. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 36(3), 453–472.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Balluchi, F., Lazzini, A., Torelli, R. (2020). CSR and Greenwashing: A Matter of Perception in the Search of Legitimacy. In: Del Baldo, M., Dillard, J., Baldarelli, MG., Ciambotti, M. (eds) Accounting, Accountability and Society. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41142-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41142-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-41141-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-41142-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)