Abstract

Our understanding of headache-attributed burden (described in Chap. 4) comes in the main from formal epidemiological studies. This chapter reports a complementary global enquiry by the World Health Organization and Lifting The Burden, not only into the impact of headache in countries around the world but also into how, if at all, healthcare systems in these countries were responding to headache. Depressingly, the enquiry found worldwide neglect of major causes of public ill health, and inadequate responses to them everywhere.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Headache disorders

- Impact

- Awareness

- Health policy

- Public health

- Education

- World Health Organization

- Global Campaign against Headache

1 Introduction

The Global Burden of Disease study 1990 (GBD1990), the first such study, conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), had nothing at all to say about headache disorders in general or any one of them specifically. They were not thought to be of any importance in global public health. The reason was lack of evidence. WHO’s perfectly correct criteria for priority gave importance to diseases that were ubiquitous, prevalent, disabling and treatable. In 1990, headache did not evidentially meet these.

Ten years later, GBD2000 was also conducted by WHO, with collaborators intent on the inclusion at least of migraine. At that time, the published prevalence data for migraine, coming mostly from Western Europe and North America, yielded an estimated global mean of about 11%. WHO transformed these into disability data using their metric of years of life lost to disability (YLDs). The outcome was a revelation: migraine was among the top 20 causes of disability (19th), accounting for 1.4% of all YLDs worldwide [1].

Sceptical questions were raised about how exact this disability estimate was, and later estimates in fact revised it substantially upwards ([2, 3]; also, Chaps. 4 and 9), but it nonetheless changed perceptions of migraine permanently. It could never again be doubted that its public-health impact was substantial.

2 The Global Campaign Against Headache

WHO’s response was to recognize headache disorders as a global public-health priority, which they did first in an internal publication coming out of an expert technical consensus meeting in Geneva [4] and then by crystallizing discussions, which had been ongoing throughout this period, into action. The outcome, after a period of planning, was the launch of the Global Campaign against Headache ([5]; also, Chap. 14), followed by its diligent pursuit [6,7,8,9,10].

2.1 Knowledge for Action

In order to address the problem of headache, the ultimate purpose of the Global Campaign, it was necessary first to know much more of its nature, scope and scale—that is, the burden of headache—everywhere in the world. Knowledge for action was therefore the first of the three originally conceived objectives of the Global Campaign [5, 6]. In 2003, when it launched, very little was known of this burden for more than half the people of the world. Most of the Western Pacific, including China, all of South East Asia, including India, all of Eastern Europe, including Russia, most of Eastern Mediterranean and most of Africa were data-free [11].

The Global Campaign filled the major knowledge gaps by undertaking new population-based studies, in Georgia, Russia, Lithuania, Turkey, China, Mongolia, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Ethiopia, Zambia, Cameroon, Benin and Peru so far, an action programme still in progress [10]. This enquiry, focused first on adults but now extending to children and adolescents, assesses both prevalence and burden and informs the ongoing Global Burden of Disease studies (Chap. 9).

2.2 Awareness

Knowledge informs policy by creating awareness: recognition that change is needed, and the second of the three originally conceived objectives of the Global Campaign [5, 6]. Awareness is the prerequisite for action to make change happen (the third and ultimate objective [5, 6]), implementing solutions proposed on the basis of knowledge.

To complete the picture of the public-health problem that action must address, global enquiry, complementary to formal epidemiological studies, was also needed into how, if at all, healthcare systems were responding to headache. WHO had initiated its Project Atlas for this very purpose: to collect, compile and disseminate information on healthcare resources in countries, for various domains of mental and neurological services and conditions of public-health priority. The Atlas of Headache Disorders and Resources in the World 2011 [12], an important addition to this series, presenting information from more than 100 countries, was undertaken by WHO and Lifting The Burden jointly as a project within the Global Campaign.

Most of the information was collected through a questionnaire survey of neurologists, general practitioners and patients’ representatives, performed from October 2006 until March 2009. Only epidemiological data of sound provenance were included: those supported by peer-reviewed publication, comprehensively compiled by systematic review [11], and those of verifiably high quality gathered in population-based studies undertaken within the Global Campaign but not all published at the time [10].

3 Messages from WHO’s Atlas of Headache

3.1 The “Neglected” Public-Health Problem

Prevalence studies included in the Atlas estimated that half to three quarters of adults in the world reported headache at least once in the preceding year [12]. This may have reflected interest bias, but the 10% reporting migraine is now known to be a substantial underestimate [2, 3]. Extrapolation from estimates of migraine prevalence and attack incidence suggested that 3000 migraine attacks occurred every day for each million of the general population [13]. Episodic tension-type headache (TTH) was the most common headache disorder; over 70% prevalence was reported in some populations (probably an overestimate, inflated by inclusion of infrequent episodic TTH [11]). Worldwide, its 1-year prevalence appeared to vary greatly, with an average of 42% in adults [11, 12]. Between 1.7 and 4% of adults were affected by headache on 15 or more days every month; medication-overuse headache (MOH), the most prevalent secondary headache, was reported in more than 1% of some populations [14].

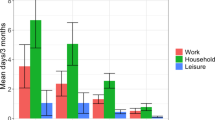

Headache disorders were most prevalent during the productive years of adulthood (30s–50s). Their estimated financial cost to society—principally from lost working hours and reduced productivity due to impaired working effectiveness [15]—was therefore enormous (see Chaps. 4 and 12). In the UK it was noted, for example, some 25 million working or school days were lost every year because of migraine alone [13].

The Atlas concluded [12]:

“Headache disorders are ubiquitous, prevalent, disabling and largely treatable, but under-recognized, under-diagnosed and under-treated. Illness that could be relieved is not, and burdens, both individual and societal, persist. Financial costs to society through lost productivity are enormous—far greater than the health-care expenditure on headache in any country.”

3.2 The “Inadequate” Healthcare Response

Against this background of obvious burden and healthcare need, only 18% of countries that responded undertook any evaluation, for health policy, of the societal impact of headache [12]. Only 12% included headache disorders in an annual health-reporting system, and even fewer, 7%, included them in national expenditure surveys [12].

Worldwide, headache management reportedly depended on self-treatment by 50% of those with headache, without consultation with any health professional [12]. This is not in apparent conflict with ideal healthcare provision, since more than 50% should be able to self-manage perfectly well ([16]; also, Chap. 15), but almost certainly it reflects biased reporting by professionals who see patients (usually at the bad end of the spectrum) rather than people with headache. Up to 10% were treated by neurologists, although fewer in the African Region and South East Asia [12]. The top three causes of consultation for headache, in both primary and specialist care, were migraine, TTH and these in combination. MOH as a cause of specialist consultation increased in frequency (1–10%) with country income [12], but this might reflect ease of access to care rather than prevalence. Overall, a minority of people with headache disorders were professionally diagnosed: the estimated proportions were 40% for migraine and TTH and only 10% for MOH [12]. If these were reflective of quality and reach of headache services, they indicated much room for improvement in all regions. They might in fact be overestimates, but the last is anyway a major cause for concern since MOH cannot effectively be self-managed or brought under control if not diagnosed.

Specialists used International Headache Society diagnostic criteria (at that time, the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition [17]) to support diagnosis in 56% of countries that responded: usage was lower in African and Eastern Mediterranean Regions and South East Asia, and lowest in low-income countries [12]. Investigation rates, mainly for diagnostic purposes, were high, despite that investigations are usually not needed to support diagnosis. Instruments to assess impact of headache were used routinely in only 24% of countries that responded, and very little in lower-middle- or low-income countries [12]. Management guidelines were in routine use in 55% of responding countries, but much less commonly in low-income countries. Despite there being a range of drugs with efficacy against headache, countries in all income categories identified non-availability of appropriate medication (probably referring to limited reimbursement) as a barrier to best management [12]. Among specific antimigraine drugs, ergotamine—cheaper, but less effective, more toxic, liable to accumulate and with greater overuse potential—was more widely available than triptans. Among alternative and complementary therapies, physical therapy, acupuncture and naturopathy were clear preferences, at least one of these being in the top three such therapies in all regions and all income categories [12].

The Global Campaign has advocated structured headache services as a key component of good healthcare, and the only effective, efficient and equitable means of delivering it ([16]; also, Chap. 15). A third of responding countries recommended, as a proposal for change, improved organization and delivery of healthcare for headache [12].

The Atlas concluded [12]:

“Health care for headache must be improved, and education is required at multiple levels to achieve this. Most importantly, health-care providers need better knowledge of how to diagnose and treat the small number of headache disorders that contribute substantially to public ill-health.

Given the very high indirect costs of headache, greater investment in health care that treats headache effectively, through well-organized health services and supported by education, may well be cost-saving overall.”

3.3 Education: The Underlying Deficiency

Worldwide, the survey found, headache disorders were taught during only 4 h of formal undergraduate medical training, and 10 h of specialist training. Better professional education ranked far above all other proposals for change (75% of countries that responded), and lack of education was seen as the key issue impeding good management of headache [12].

3.4 National Professional Organizations

A national professional organization for headache disorders (or headache chapter in another organization) existed in two-thirds of countries that responded, with a very marked difference between high- and upper-middle-income, on the one hand (71–76%), and low-income countries, on the other (16%) [12]. The true numbers might be much lower, since respondents were much more readily identified in countries where such organizations existed.

A minority (20%) of professional headache organizations participated in the construction of postgraduate training curricula on headache, and only 10% engaged in the development of undergraduate curricula [12]. Rather more (over one third) arranged conferences, raised awareness of headache-related issues or were involved in setting guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of headache (a low-cost opportunity for substantial service improvement).

3.5 A Template for Action

The Atlas went beyond descriptions of this dismal status quo, and the issuing of political messages to the world’s national governments. It set out an account of the way forward, in a template for action. More is said of this in Chap. 14.

4 Concluding Remarks

What were the findings of this first global enquiry into these matters? They were that headache disorders were ubiquitous, prevalent, disabling and largely treatable (therefore meeting all criteria for priority), but under-recognized, underdiagnosed and undertreated. Very large numbers of people disabled by headache did not receive effective healthcare. Illness that could be relieved was not, and burdens, both individual and societal, persisted. The barriers responsible for this might vary throughout the world, but poor awareness of headache in a context of limited resources generally—and in healthcare in particular—was constantly among them [12]. In summary, the Atlas described “worldwide neglect of major causes of public ill-health, and the inadequacies of responses to them in countries throughout the world” [12]. Yet the financial costs to society through lost productivity were far greater than the healthcare expenditure on headache in any country.

These were messages from WHO directly to the governments of the world.

Raising awareness is the purpose of this monograph, and all of the topics introduced in this section are subjects of its later chapters.

References

World Health Organization. World health report 2001. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abdulkader RS, Abdulle AM, Abebo TA, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abu-Raddad LJ, Ackerman IN, Adamu AA, Adetokunboh O, Afarideh M, Afshin A, Agarwal SK, Aggarwal R, Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Ahmadieh H, Ahmed MB, Aichour MTE, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aiyar S, Akinyemi RO, Akseer N, Al Lami FH, Alahdab F, Al-Aly Z, Alam K, Alam N, Alam T, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59.

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858.

World Health Organization. Headache disorders and public health. Education and management implications. Geneva: WHO (WHO/MSD/MBD/00.9); 2000.

Steiner TJ. Lifting The Burden: the global campaign against headache. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:204–5.

Steiner TJ. Lifting The Burden: the global campaign to reduce the burden of headache worldwide. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:373–7.

Steiner TJ, Birbeck GL, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Martelletti P, Stovner LJ. Lifting The Burden: the first 7 years. J Headache Pain. 2010;11:451–5.

Steiner TJ, Birbeck GL, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Martelletti P, Stovner LJ. The Global Campaign, World Health Organization and Lifting The Burden: collaboration in action. J Headache Pain. 2011;12:273–4.

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Dua T, Birbeck GL, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Martelletti P, Saxena S. Time to act on headache disorders. J Headache Pain. 2011;12:501–3.

Lifting The Burden. The Global Campaign against Headache. http://www.l-t-b.org.

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, Steiner TJ, Zwart JA. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210.

World Health Organization, Lifting The Burden. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

Steiner TJ, Scher AI, Stewart WF, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Lipton RB. The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, gender and ethnicity. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:519–27.

Castillo J, Munoz P, Guitera V, Pascual J. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190–6.

Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Lost workdays and decreased work effectiveness associated with headache in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:320–7.

Steiner TJ, Antonaci F, Jensen R, Lainez JMA, Lantéri-Minet M, Valade D on behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache. Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J Headache Pain. 2001;12:419–26.

International Headache Society Classification Subcommittee. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1–160.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Steiner, T.J., Huynh, N., Stovner, L.J. (2019). Headache Disorders and the World Health Organization. In: Steiner, T., Stovner, L. (eds) Societal Impact of Headache. Headache. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24728-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24728-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-24726-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-24728-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)