Abstract

The indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness of households have attracted attention in academic research and in society at large. In this chapter, we summarize current research on indebtedness and over-indebtedness with especial emphasis on efforts and attempts to derive a more precise and applicable definition of the concept of over-indebtedness. With a more nuanced definition of the concept that can be operationalized in practice, one can more accurately estimate the societal costs of over-indebtedness. Particularly important, it makes it possible also to conduct more in-depth studies about the implications of indebtedness and over-indebtedness for the physical and psychological wellbeing of young adults. Relying on the distinction between active and passive over-indebtedness, we argue that the causality between indebtedness, over-indebtedness, and health is not necessarily unilateral.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness of households have attracted attention for a long time in academic research and in society at large. Many studies and authorities report increasing indebtedness among the average household during the past decades in most Western countries (e.g., BIS , 2007; D’Alessio & Iezzi , 2013; Disney , Bridges , & Gathergood , 2008). In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, this phenomenon and its related problems seem to have spread elsewhere, especially to the emerging market economies (Lombardi , Mohanty , & Shim , 2017). Before the financial crisis, studies document a substantial increase in the ratio of household debt to disposable income in Western countries, like the UK. Disney et al. (2008) report that in the six years prior to the crisis (i.e., between 2002 and 2008), British households’ secured loan debts to post-tax income increased by nearly 50%—from around 80% to almost 120%. Statistics also disclose a similar pattern for household indebtedness in Sweden, which is the country of focus in this book. According to an extensive overview made by Bank for International Settlements (BIS , 2016), the debt ratio of Swedish households does in fact belong to the highest in the world. The major part of household indebtedness in Sweden is in the form of secured (collateralized) loans such as mortgage loans (i.e., mortgages). The indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness of young adults are more likely to be in the form of unsecured (non-collateralized) debt in various types of consumer credits, such as card credits, leasing and payday loans.

The current knowledge of indebtedness and over-indebtedness of young adults and the implications for their physical and psychological wellbeing is suggestive at best (Shim , Xiao, Barber, & Lyons , 2009). On the one hand, it is widely documented that there is a relationship between debt reliance and wellbeing (see, e.g., the meta-analysis conducted by Richardson , Elliott , & Roberts , 2013). There is also evidence that young adults rely on debt, as illustrated by Brown, Grigsby, van der Klaauw, Wen, and Zafar (2015), which show that young adults in the US are indeed heavily debt reliant. On the other hand, young individuals’ excessive debt reliance seems to go well in hand with Franco Modigliani’s well-known life cycle hypothesis suggesting that young adults should be expected to be more indebted relative to their income (Modigliani, 1966). Hence, high debt ratios of young adults do not necessarily mean that they are over-indebted in that ‘young families expect their future income to grow and spend more than they earn, thus accumulating debts that they will repay when they are more mature’ (D’Alessio & Iezzi , 2013: 3). The crux of the matter is how to define over-indebtedness. 1 According to Betti , Dourmashkin, Rossi, and Ping Yin (2007: 138), ‘[t]here is currently no general agreement on the appropriate definition of consumer over-indebtedness, on how to measure it or on where to draw the line between normal and over-indebtedness’. This task is far from trivial and, accordingly, Schicks (2013) concludes that there was still no unanimous definition of the concept at the time of her study. In the literature, the following three types of operationalization are commonly used in order to measure and assess the impact of over-indebtedness of individuals and households (see, e.g., Betti et al., 2007; Ferrira , 2000):

-

1.

The objective approach, where the debt burden is calculated based on the individual’s or household’s debt to asset or debt-to-income ratio.

-

2.

The subjective approach, which allows individuals or household representatives to estimate their own perceived abilities to pay their debt.

-

3.

The administrative approach in which administrative records are used to collect data about, for example, number of payment defaults, bankruptcies, applications for debt restructuring, etc.

In this chapter, we summarize current research on indebtedness and over-indebtedness with especial emphasis on efforts and attempts to derive a more precise and applicable definition of the concept of over-indebtedness. With a more nuanced definition of the concept that can be operationalized in practice, one can make more accurate estimations of the societal costs of over-indebtedness. Particularly important, it makes it possible also to conduct more in-depth studies about the implications of indebtedness and over-indebtedness for the physical and psychological wellbeing of young adults. Relying on the distinction between active and passive over-indebtedness (e.g., Gloukoviezoff , 2007; Ramsay , 2003; Sullivan , Warren , & Westbrook , 2000; Vandone , 2009), we argue that the causality between indebtedness, over-indebtedness and health is not necessarily unilateral.

The chapter is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide a brief literature overview of the increasing debt reliance and over-indebtedness of individuals and households. We also describe and discuss a selection of the various definitions and measurements of over-indebtedness and how these are linked to related concepts, such as financial literacy and financial exclusion. In Sect. 3, we present some descriptive statistics of indebtedness and over-indebtedness in Europe. As several studies indicate that institutional differences matter for the scope and face of over-indebtedness (see, e.g., Raijas , Lehtinen , & Leskinen , 2010; Ramsay , 2012), we zoom in on Sweden at the end of the section. Section 4 then concludes the chapter with a summary and discussion on implications for the studies conducted within the research program.

2 A Brief Literature Overview

Household over-indebtedness started to attract attention in the late 1980s (Ramsay , 2012). Since then, household debt in the US has tripled (Harvey , 2010), and similar trends are identifiable across the world (see Krumer-Nevo , Gorodzeisky , & Saar-Heiman , 2017, for an overview). There seems to be consensus on that the widely observed increasing debt reliance of households can be driven by various factors. According to Johansson and Persson (2007), it is useful to distinguish between two factors, which they believe have played a fundamental role for why the average household has taken on more debt over the past decades. The first factor is related to greater accessibility for consumers to financial markets after the financial deregulations back in the 1980s. The deregulation wave more or less erased existing lending constraints that until then had hampered household borrowing. The second factor brought forward by the authors is the (ever) falling lending rates. The lending rates have in fact continued to fall in the 2010s to historically low levels in both nominal and real terms. In our recent comparison of the development of Swedish banks’ mortgage lending and funding rates from 2000 to 2016 (Elliot & Lindblom , 2017), we find that the offered lending rates by the banks were gradually reduced over the time period. After temporary recoil, caused by the financial crisis, the offered rates on mortgage loans with different maturities were in January 2016 down to approximately only one-third of the corresponding rates offered at the beginning of the Millennium.

Anderloni and Vandone (2008) offer a more comprehensive dichotomy by dividing the plethora of causes of the increasing indebtedness into macro- and micro-level reasons. The former includes general societal trends such as increasing credit supply, labor market structure, household inequality, or housing costs. The latter micro-level reasons include excessive credit usage, favorable credit attitudes, financial illiteracy and various life process events (such as illness or divorce). According to Krumer-Nevo et al. (2017), these two perspectives could be viewed as fundamentally different in the sense that macro-level reasons stress the defective social structures, whereas the micro-level reasons set focus on irresponsible individual behavior and ignorance. The authors argue for a midway explanation, where it is the interaction between personal and systemic hardship that forms the principal cause of what they define as over-indebtedness.

Under the midway framework suggested by Krumer-Nevo et al. (2017), physical and mental health issues are indeed described as a cause for over-indebtedness (see Caputo , 2012). However, it is equally common to view such problems as an effect of identified over-indebtedness (cf., Ahlström & Edström , 2014; Larsson , Svensson , & Carlsson , 2016; Sweet , Nandi, Adam, & McDade, 2013). Larsson et al. (2016) refer to studies that have shown that observed over-indebtedness may cause an increase in smoking, back-pain and obesity. Sweet et al. (2013) find a strong relationship between what they classify as over-indebtedness among young adults in the US and psychological distress, such as higher perceived stress and depression, worse self-reported general health, and higher diastolic blood pressure. To make matters worse, Kalousova and Burgard (2013) attract attention to the fact that individuals with high levels of debt are also less likely to afford suitable healthcare. Moreover, in a recent study conducted for the Swedish Consumer Agency (SCA), Ahlström and Edström (2014: 10) note that over-indebted individuals ‘displayed a significantly higher incidence of both suicidal thoughts and attempted suicide, compared with the general population (e.g., 17.6% have attempted to take their own lives, compared with 3.6%, which translates to an incidence almost five times as high)’.

What then is being done about the problem of too high indebtedness? In general, there are two levels of institutional interventions: (i) various public policy measures and (ii) measure where the individual debtor is the target. Policy measures, such as credit market regulation, early identification and prevention, are further discussed in the final Chapter 8 of this book. The individual measures include both motivational and reactive measures.

The motivational measures encompass, for instance, financial literacy aspects and other awareness-raising incentives (see Sect. 2.3 below). The main reactive measures are various forms of either public or private financial advice/counseling and debt reconstruction through negotiations with credit companies (Larsson et al., 2016; Stamp , 2012). Studies investigating the impact of such financial advice generally find that debtors are positive (Orton , 2009; Pleasence & Balmer , 2007; Stamp , 2012). A recent European Commission report (EC , 2013: 13) concludes that ‘interviewees tended to report positive outcomes as a result of seeking advice or taking measures to alleviate their difficulties, supporting the finding that most consumers find the experience of over-indebtedness distressing, want to repay their debts, and if they are unable to, want to find an equitable solution to their debt problems’.

In sum, since the 1980 over-indebtedness among individuals and households has attracted increasing attention from both policy-setters and academics, but we still have much to learn about the reasons for over-indebtedness, the implications of over-indebtedness and not least what to do about it. One area, which is still under debate, is how to actually define and measure over-indebtedness. We will discuss and elaborate on this below.

2.1 Definitions of Over-Indebtedness

To define over-indebtedness, it makes sense to start in the concept of household debt and the household’s ability to pay off debt (Krumer-Nevo et al., 2017). The latter is of course vital. The average household’s higher indebtedness, in terms of widely reported increasing debt ratios, may seem to imply that a larger proportion of households have become over-indebted. However, average numbers based on aggregate data can often be misleading. Disney et al. (2008: 11) assert that the concept of over-indebtedness ‘should certainly not be confused with the existence of high levels of debt in the economy’. Households differ in economic/financial strength and, as Johansson and Persson (2007: 235) point out, the definitions of household tend to vary between surveys since: ‘[a] household can either be defined as two adults living together (or one adult living alone) with children below the age of 18, or, basically, as the individuals living under one roof’. Referring to the “return-to-scale effect” of living together when it comes to living expenses, the authors clarify that study results will be different depending on the applied definition by giving the following example: ‘a 20 year-old male living with his parents may look financially constrained, until one takes into account that his parents are paying for at least some of his running costs’ (ibid.: 236).

Clearly, the actual debt reliance of households is likely to be unevenly distributed between different types of households with respect to their capacity and capability to manage instalment and interest payments on their debt. This suggests that one should adopt a balance sheet perspective. The balance sheet perspective implies that we need to consider both the size of household debts (D), and the size or, more accurately, the market value of their financial, real as well as intellectual assets (MVA). In principle, these assets’ market value is equal to current cash holdings (CF0), that is, their cash flow at time 0, and the present value (PV) of expected future net inflow of cash (E(CFt)) in each period t. These expected cash flows will primarily consist of net wage income (after living expenses), dividends and capital gains. 2 If MVA > D, the household has a positive net wealth. Hence, if efficient financial markets are accessible at negligible costs, the individual household (or young adult) would be able to manage its debt in accordance with the life cycle hypothesis as long as the market value of its assets exceeds outstanding debts. 3 However, a positive net wealth of a household does not rule out the possibility that it is over-indebted.

From an economic perspective, over-indebtedness arises when a marginal increase in a household’s debt decreases its expected utility or, in other words, when debts exceed the optimal debt level. This theoretical definition falls within the objective approach, but the theoretical model can hardly be operationalized in practice without major modifications and adjustments—if even then. The expected utility of individuals and households is difficult to measure. 4 Moreover, given available data, it is more or less impossible to forecast expected future net cash flows of existing and potential assets with some degree of accuracy, let alone to determine the relevant discount rate(s) of these flows. Adding to the complexity, in real life there are both assets and debts of different types with respect to, for example, time to maturity and varying levels of sensitivity to unexpected events or altered conditions. Nevertheless, the model provides a useful illustration of important relationships and can help us to better understand the nature of the concept of over-indebtedness from an economic perspective. The intuition of this simple theoretical set-up implies that at some degree of indebtedness, the financial risk-taking of a household will be too high and result in a lowered expected ability to pay off its debt. Consequently, there will be a more pronounced risk that the asset side of the balance sheet will not match outstanding debts on the liability side.

Adopting the objective approach, Kempson , McKay, and Willitts (2004) divide household debt into two separate concepts. Debt can refer to “normal” debt (also called consumer debt), or it can refer to households that are “in debt”, i.e., that have fallen behind on payments and/or household bills. Normal debt includes the essential debts for maintaining an economic balance and smooth consumption over a life cycle, such as mortgage loans, car loans and deferred credit card payments (see also Yoon , 2009). These debts are normalized and held by the majority of the population in most countries. As will be deliberated on in Sect. 3.2, Swedish households are among the most frequent users of these types of debt. However, historically Swedish households have been reluctant to use credit facilities for consumption purposes, but in recent years there has been a quick expansion also in consumer credits (Riksbank , 2017).

As implied by its name, the subjective approach leaves to the individuals or households them-selves to define over-indebtedness as they ‘are the best judges of their own net debt/wealth position ’ (Betti et al., 2007: 144). Such a definition is of course barely operational as it may vary substantially between different people on what is believed to be too heavy debt reliance. Furthermore, it is likely that some households have better and others poorer financial understanding. In combination with the objective and/or administrative approach, however, it may make sense to also take into account the view of debtholders to better understand and assess implications and/or possible causes of over-indebtedness (see, e.g., D’Alessio & Iezzi , 2013).

Under the administrative approach, over-indebtedness is regarded as an identified personal debt problem or realized problem debt. As such, it includes one or more financial commitments that an individual or a household has been unable to meet. Empirical research documents that over-indebtedness is often a result of credit card debts that are not paid on time. Anderloni and Vandone (2008) note that over-indebtedness includes the inability to pay routine bills (such as taxes, living expenses, or rent) on time. In search for a common operational definition of over-indebtedness, Davydoff et al. (2008) review administrative definitions and measurements of the concept adopted at EU level and in Member States. This review was contracted by the European Commission (EC) and part of a comprehensive assessment of over-indebtedness in Europe. In a subsequent report five years later, which was also contracted by EC, an operational definition of household over-indebtedness is provided in accordance with the administrative approach as follows: ‘households are considered over-indebted if they are having—on an on-going basis—difficulties meeting (or falling behind with) their commitments, whether these relate to servicing secured or unsecured borrowing or to payment of rent, utility or other household bills. This may be indicated by, for example, credit arrears, credit defaults, utility/rent arrears or the use of administrative procedures such as consumer insolvency proceedings’ (EC, 2013: 21).

While the authors of the report withhold that time may have come to abandon the attempts to further define over-indebtedness, they stress the importance of focusing on tackling the problems related to over-indebtedness. However, the problem of not having agreed upon a definition of the concept materializes when trying to measure the magnitude and economic consequences of over-indebtedness. This is perhaps best illustrated by two recent Swedish governmental reports, which have tried to put a dollar amount on the societal costs of over-indebtedness. In the first report, the Swedish Enforcement Authority (SEA) relied on a broad definition of over-indebtedness. They estimated that 400,000 people in Sweden at the specific time point were over-indebted at a societal cost of SEK 30–50 billion (SEA, 2008). Only a few years later, the Swedish National Audit Office (SNAO) implemented a narrower definition of over-indebtedness and concluded that approximately 30,000 people in Sweden were then over-indebted at an estimated societal cost of just under SEK 10 billion (SNAO, 2015). This shows that the definition can have a large impact, especially in light of the policy attention and types of interventions that these different estimates could entail. In order to approach a definition of over-indebtedness that can be operationalized in practice, it is useful to discuss two constructs that are closely related to over-indebtedness but are usually treated separately; financial exclusion and financial literacy.

2.2 The Relationship Between Over-Indebtedness and Financial Exclusion

Over-indebtedness and financial exclusion are generally treated as two rather different concepts, and as such, different research streams. However, as illustrated by Gloukoviezoff (2007), there is a strong link between the two and for the single individual or household there may be a very thin line between being excluded from the financial market (i.e., turned down by the bank or another financial intermediary) and ending up in severe indebtedness.

Financial exclusion is commonly defined as ‘those processes that serve to prevent certain social groups and individuals from gaining access to the financial system’ (Leyshon & Thrift , 1995: 314). According to Koku (2015: 655), financial exclusion can be divided into five different forms:

-

(i)

Access exclusion: the restriction of access through the processes of risk management.

-

(ii)

Condition exclusion: where the conditions attached to financial products make them inappropriate for the needs of some people.

-

(iii)

Price exclusion: where some people can only gain access to financial products at prices they cannot afford.

-

(iv)

Marketing exclusion: whereby some people are effectively excluded by targeting marketing and sales.

-

(v)

Self-exclusion: people may decide that there is little point applying for a formal financial product because they believe they would be refused.

The link between financial exclusion and over-indebtedness can be described through these different forms as follows. Consider a borrower that approaches a bank but is denied a loan because she or he is considered too risky (access and price exclusion). The borrower still has a need and is, thus, referred to another financial institution, which can be a shadow bank actor with less favorable terms. Not unlikely, the borrower is a young adult that makes purchases by utilizing card credit loans or unsecured instant loans with comparably much higher interest rates than the lending rates on conventional bank loans. Even if the initial debt amounts are often small, as interest rates accumulate, the borrower finds it harder and harder to pay back the debt and, finally, ends up in over-indebtedness. Similarly, responsible lenders may not offer the types of financial products that sensitive borrowers need (condition and marketing exclusion). Finally, the borrower may think that she or he will be denied by the bank and, hence, decide to utilize other lenders, with less favorable terms, instead (self-exclusion).

In essence, growing outstanding debts can lead to financial exclusion from the traditional banking sector, which forces the borrower to seek help from the nontraditional shadow bank sector and move further into indebtedness problems. The initial small debts can lead to a rapid spiral of additional debts and a loss of hope of ever becoming financially balanced. This makes the borrower end up in severe over-indebtedness, which may finally lead to financial exclusion .

2.3 The Relationship Between Over-Indebtedness and Financial Literacy

Several studies investigate the role of financial literacy and knowledge in mitigating over-indebtedness (see Chapters 5–7 of this volume). The basic idea is that if we can educate people to make better financial decisions, they would be less prone to end up in severe financial problems. However, Walker (2012) argues that this idea places too much responsibility on the single individual. Frade (2012) follows a similar line of argument and withholds that severe indebtedness problems cannot simply be resulting from lack of knowledge, but rather that we must account for structural factors (such as the financial crisis and the demand side of credit as discussed in Chapter 8 of this volume ). Rueger , Schneider, Zier, Letzel, and Muenster (2011) add further complexity by acknowledging individual factors such as changes in economic situation following, for instance, illness or divorce.

2.4 Measuring Over-Indebtedness in Practice—An Illustration

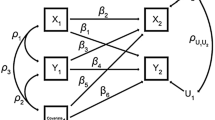

From the literature reviewed in this chapter, we recognize that it is a very real challenge in practice to accurately identify, measure and determine over-indebtedness of individuals and/or households. As we have already stated, our rather straightforward theoretical model, based on ordinary discounting techniques, cannot be directly applied to determine at what level of indebtedness an individual or a household has borrowed too much and, thus, is to be classified as over-indebted. Given the many dimensions/aspects of individuals’ and households’ excessive debt reliance, and the obvious uncertainty embedded in estimations of future cash flows, such a model could at best indicate over-indebtedness or the risk thereof. Based on their literature review and analysis of the most commonly applied models and approaches to measure over-indebtedness, D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) arrive at the conclusion that a definition of the concept that can be operationalized in practice must be multidimensional. They find that recent literature seems to agree upon a “common set of indicators”, which can be used to assess over-indebtedness. At the same time, they cannot find that the literature converges on which indicator is to be regarded as superior when it comes to capturing the actual over-indebtedness of an individual or a household. For different reasons, like lack of access to valid and reliable information, uncertainty and asymmetric information, each indicator has its pros and cons. Hence, they adopt a multi-indicator approach reflecting four aspects of household over-indebtedness: The household (i) makes high debt repayments in relation to disposable income, (ii) is in arrears, (iii) relies too heavily on debts, and (iv) perceives debt as a burden in daily life.

In the remaining of this section, we briefly present the measurement model adopted by D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) to illustrate a systematic and well-founded multi-indicator approach on how the four aspects can be operationalized in practice to assess and measure over-indebtedness of households. In this model, each of the last three aspects is supposed to be captured by using only one indicator, respectively. The second aspect falls under the administrative approach. The authors use an indicator by which they seek to identify “structural arrears” related to failed repayments of secured loans, such as mortgages, and unsecured consumer loans including bills with over two months overdue. The third aspect is covered with an indicator by which too heavily debt-reliant households can be distinguished. In accordance with Kempson (2002), who distinguishes a high correlation between individuals’ debt problems, such as being in arrears, and their number of loan engagements when adopting the UK Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) “Task Force on Tackling Over-Indebtedness”, D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) classify a household as over-indebted, in their main analysis, if the household has at least four loans. 5 Due to lack of information, the fourth (subjective) aspect—a household’s subjective perception of burdensome debt in daily life—could not be directly captured by the authors with a specific indicator. Instead they use households’ answer on a question whether the monthly income was considered as sufficient for “making ends meet” as a benchmark for assessing such an indicator. Households that answered they managed to make ends meet “with difficulty” or “with great difficulty” were then classified as perceiving their indebtedness burdensome and, thus, over-indebted.

The first aspect of household over-indebtedness—the extent to which a household makes high debt repayments (P) in relation to disposable income (Y)—the authors cannot capture by just one indicator (IP). Hence, they use three different indicators to assess this aspect, which sorts under the objective approach. The debt (repayment)-to-income ratio (IP = P/Y) is then chosen as one indicator. In their main analysis, the authors use a threshold of 30% debt repayment of disposable income to single out possible over-indebtedness. 6 Because of the heterogeneity of households, with respect to levels of income and wealth, the debt repayment-to-income indicator is in turn separated into three sub-indicators in the analysis. The second indicator used to cover part of the first aspect could be referred to as a “below the poverty line” indebt indicator. The authors use this indicator to classify an indebted household as over-indebted if the poverty line exceeds disposable income after debt repayments. Finally, the first aspect is also partly assessed with what may be called an unsecured debt repayment indicator. In their main analysis, the authors identify households that use over 25% of their income for repaying unsecured debts. In addition to their main analysis, the authors conduct sensitivity analyses in which alternative thresholds are used for the various indicators.

The division of the debt repayment-to-income indicator (IP) into three sub-indicators to more accurately assess whether a household is making too high debt repayments, in relation to disposable income, is being motivated by the fact that for some households, like high-income households, a 30% threshold on this indicator would barely have any impact on their way of living. Accordingly, wealthier households may easily manage high debt repayments by resorting to their savings or selling some of their other financial short-term and/or long-term assets. The first sub-indicator (IP1) takes into account that a household can possess short-term financial assets (AF), which it may use to partly or fully payoff outstanding debt (D). In the latter case, IP1 will equal zero. In the former case, the selling of a financial asset will generally ease the burden of debt repayment implying that IP1 is less than IP. The reverse is highly unlikely and would require that the selling of the financial asset leads to a substantial income loss (YAF) in relation to its sales value (AF). Just as selling a financial asset can be used to reduce debt, the income forgone will be deducted from the disposable income. The following formula applies:

The other sub-indicators take into account that a household may also have real assets that may be sold. The second sub-indicator (IP2) differs from IP1 in that it also includes long-term fixed assets other than homes (AR). As such assets may generate income YAR, the following formula applies:

There may also be a possibility for a household that owns a home to sell it for its net market value (AH). The third sub-indicator (IP3) takes this possibility—if existing—into account. In the unlikely case, this will lead to foregone income, any income foregone is included in YAR. Hence, the third sub-indicator (IP3) is determined accordingly with the following formula:

In the normal case, IP > IP1 > IP2 > IP3. Given the same household disposable income Y, the same threshold may be used to capture the impact on the individual household whether or not it possesses any kind of sellable assets. To accurately compare the true impact on households with low and high income would suggest the use of different thresholds.

In their analysis, D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) found that there was little overlap between the five nonsubjective indicators adopted (i.e., not taking into account the natural overlap between the debt repayment-to-income ratio indicator’s three sub-indicators). Only one out of four households that were classified as over-indebted by one of these five indicators was classified as over-indebted by at least two indicators. In that respect, the indicators seem to be complementary rather than substitutes. However, the authors report that even when the indicators are joined together, they did far from completely coincide with the households’ perceptions of having financial difficulties. Kept separately, most of the indicators poorly matched households’ perceptions. A household that was classified as over-indebted according to the first indicator did only match every second time with the household’s answer that it perceived it as difficult or very difficult to make ends meet each month. A corresponding classification by the second arrears indicator did only match every fifth time. The apparently low concordance between the indicators and benchmark adopted led D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013: 18) to conclude that ‘it is worth critically assessing both the existence of alternative indicators and the use of different cut points from those commonly used’.

When testing different thresholds for the various indicators, the authors detect that the “below the poverty line” indebt indicator is the indicator most in line with the households’ perceptions of having financial difficulties. Not taking the poverty indicator into account, the third sub-indicator (IP3) and the unsecured repayment debt indicator with a 15% cut point are shown to best fit with households’ perceptions. Although there is far from “full concordance” between the adopted indicators and households’ perceptions, which possibly could be explained by the fact that the households’ answers are just being used as a benchmark indicating their perceptions of financial difficulties, the multi-indicator approach seems still reasonable to use to operationalize the concept of over-indebtedness for assessing and measuring it in practice. In comparison to the theoretical net present value (NPV) based model, the multi-indicator approach can take into account the market value of (financial and real) assets currently possessed by an indebted individual and/or household (i.e., assets “in place”). The market values of neither intellectual assets nor expected investments in future assets are captured. However, provided there are no dramatic changes in wages and asset holdings in the future, the multi-indicator approach appears to have great potential to capture individuals’ or households’ over-indebtedness if combined with accurate measurements of perceptions of financial difficulties. In case of young adults’ possible over-indebtedness, however, dramatic changes of wages and future asset holdings make more or less a prerequisite for the life cycle hypothesis. This suggests that also the multi-indicator approach adopted by D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) needs to be modified in order to assess and measure possible over-indebtedness of young adults.

3 Indebtedness and Over-Indebtedness in Numbers

This part of the chapter uses the discussion from previous sections in order to illustrate the changing face of household indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness. We do so primarily from a European perspective by presenting some descriptive statistics of the European situation with special attention to Sweden.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics of European Households

As noted in the introduction, the world has seen ever-increasing consumer indebtedness-levels since the deregulations of the financial markets in the 1980s. Betti et al. (2007) note that this led to increasing concern among economic analysts and policy makers about negative consequences thereof. Accordingly, many developed countries are since long collecting and publishing data on indebtedness and consumer credit on a regular basis. Relying on such data, Betti et al. (2007) adopted the subjective approach to measure over-indebtedness in their survey of EU Member States in 1996. They document extensive variation between these countries when it comes to household consumer debts (not accounting for mortgages). At the high end, as much as 30–48% of the average households were found to have consumer debts in Denmark, the UK, Luxembourg, France, Ireland and Finland. At the other low end, the corresponding debt of the average households in Italy, Greece and Portugal was estimated to be between 8 and 13% only. Hence, in the remaining countries, the comparative statistic shows average household consumer debts in the range between 13 and 30%. At the same time, the reported levels of over-indebtedness (as a percentage of total households) ranged from 11% in Italy to 49% in Greece. This shows that over-indebtedness was indeed a significant problem also back in the mid-1990s. An interesting result is that over-indebtedness seems to be more severe in countries where credit is more restricted.

Even though Betti et al. (2007) offer extensive support for the use of subjective measures of over-indebtedness, government agencies generally tend to rely on the administrative approach. In particular, arrears (i.e., money that is owed and should have been paid earlier) are commonly used. Jumping ahead to 2011, EU-SILC survey data shows that across the EU area 11.4% of those surveyed had been in arrears with payments over the previous 12 months on rent/mortgage, utility bills and/or hire-purchase/loan agreements due to financial difficulties (EC , 2013).

Despite the time gap of 15 years between the two surveys and that they rely on different measures, the results are quite similar in terms of what countries have a high (low) tendency toward over-indebtedness, with Italy being an exception. The EC report shows that the majority of Member States have experienced a growing level of arrears during the surveyed time period between 2005 and 2011. The increase in arrears is particularly pronounced after the financial crisis.

It is submitted by the EC (2013) report that there is a general agreement among different stakeholders in most Member States that debt-related problems of households had continued to escalate during the past five years. In Germany, just below half of the households (49%) reported that they were over-indebted and/or found it significantly more difficult to meet their financial commitments compared to five years earlier. However, it should also be noted that one of four of the German households (23%) stated that their debt-related problems had increased only moderately.

It does not appear as if household over-indebtedness is concentrated and only applies to a particular social group. Clearly, the risk of entering into financial difficulties that may lead to over-indebtedness is very high in low income households with one or more unemployed persons. This is particularly true for young adult households with children, irrespective if they are tenants living in a rental apartment or have bought their own home partly financed by mortgages. However, other income categories are also affected. Almost every second stakeholder acknowledged a significantly worsened situation in the past five year. Here, middle income households and homeowners with mortgages are reported to be among those that experienced an increasing level of financial problems.

The most frequently reported reason for entering into high indebtedness and financial problems by consumers and other stakeholders interviewed were increasing living costs caused by higher utility costs, housing costs, daycare costs and other general living costs including food and transportation.

Figure 1 shows that the percentage of identified arrears for the average household in Europe has been slightly decreasing over more recent years, but it remains still at around 10%. This means that across Europe, one in ten households is consistently in arrears with payments on rent/mortgages, utility bills and/or hire-purchase/loan agreements.

As shown in Fig. 1, the statistics concerning the average household in the EU hide significant variation among Member States and do therefore only give an indication of the size of the problem. While the documented levels of arrears in Germany, Sweden and the UK are below the average EU-level, the reported levels of arrears in particularly Greece and, until 2015, also Italy are substantially higher. The situation in Greece is exceptional and a reflection of the many years of serious financial difficulties at an aggregate country level. Figure 1 displays that the level of arrears in Italy was, on average, not so far below the one in Greece at the beginning of the period.

According to D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013: 2), the indebtedness of households in Italy began to reach worrisome levels at the of the global financial crisis: ‘for many years the significant increase in household debt did not give rise to concern for several reasons: the initial level of household indebtedness was particularly low by international standards; the increase recorded in recent years has only filled part of the gap; the growth in indebtedness has been seen as reflecting the reduction in both nominal and real interest rates as a consequence of the increase in competitiveness in financial markets, which has reduced the cost of debt and the cases of credit constraints’. The authors acknowledge that the Italian government imposed a new consumer bankruptcy law, because of the harsh economic conditions in Italy that followed the crisis.

As described in Sect. 2.4, D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) adopted a multi-indicator approach in their attempt to increase our general knowledge of how to accurately measure (Italian) household over-indebtedness and financial difficulties and, moreover, examine what household categories are likely to enter into financing problems caused by over-indebtedness. In so doing, they used detailed data from the Italian Survey on Household Income and Wealth (SHIW) conducted in 2010 on Italian households’ income, debts and financial and real assets in place, as well as on these households’ wellbeing and perceived financial difficulties reflected by the constructed subjective benchmark. Starting in 1965, this survey is with some exceptions made every second year by the Bank of Italy. Information is gathered on the financial status and behavior of approximately 8000 Italian households. Thus, SHIW covers other data beyond income, debt and financial and real assets of the households, like their demographics and their consumption and savings behavior. According to SHIW 2010, 3.1% of the Italian households exhibited a debt (repayment)-to-income ratio (IP) greater than 30%. Also taking into account the households’ financial and real assets, the correspondent percentage was only 1.1% measured by the third sub-indicator (IP3).

Using the “below the poverty line” indebt indicator, the authors identified about six percent of the households as poor. Each of the remaining three indicators classified the households as over-indebted by around or less than one percent. Considering the indicators’ overlapping, 8.2% of the Italian households were identified as over-indebted by at least one of the adopted indicators. In aggregate, about 3.5 times as many, or nearly 30% of all households, perceived that they were struggling to make ends meet every month with difficulty or great difficulty. Broken down on age groups, young adults (≤30 years old) were the ones experiencing financial problems to the greatest extent (37.3%). However, almost three of four households (74.8%) with the lowest income (1st quintile) perceived financial difficulties. This implies that relatively large numbers of the households regard themselves as over-indebted without this being captured by any of the indicators used.

As already commented upon in Sect. 2.4, there were also many households that did not perceive themselves to have financial difficulties, in terms of managing to make ends meet every month with difficulty or great difficulty, despite being identified as over-indebted by one or more indicators. This suggests possible financial exclusion and that many households with very low income were not regarded as qualified to get any loans. With no loans, these households are rarely identified as over-indebted by commonly adopted indicators.

Table 1 shows arrears for different types of households in the EU from 2010 to 2017. It is quite clear that households with dependent children are overrepresented among the high level of arrears. At the same time, arrears in the EU seem to be decreasing in all types of households.

In fact, while it is relatively accepted in the academic literature that unsecured credit is positively associated with the likelihood of arrears, it has been much more difficult to establish a relationship between levels of mortgages and levels of arrears (EC , 2013). There are two competing explanations for the relationship between unsecured consumer credit and arrears: either higher levels of such credit put households in a riskier financial position, or households with lower income are more likely to take on unsecured consumer credits in order to pay arrears on housing and/or utility.

As is discussed next, the apparent low relationship between mortgages and arrears levels may, on the one hand, be positive for Swedish households as the vast majority of household debt in Sweden constitutes of secured loans (i.e., mortgages). On the other hand, and as noted earlier, unsecured consumer credit has been growing quickly in Sweden in recent years making Swedish households more exposed to future potential over-indebtedness.

3.2 Estimations of Societal Costs and Wellbeing Related to Over-Indebtedness in Sweden

The two earlier mentioned governmental reports (see the end of Sect. 2.2), which were conducted on the behalf of the SEA and the Swedish National Debt Office (SNDO), respectively, are examples among a small collection of attempts made by Swedish authorities to estimate societal costs associated with individuals’ and households’ over-indebtedness defined according to the administrative approach. The divergent outcomes of the estimations, ranging from SEK 10 billion up to as much as SEK 50 billion per year, demonstrate how difficult it is to make consistent estimates of such costs in the real world. However, even if SEK 10 billion/year represents only a 20% fraction of SEK 50 billion/year, apparently it still represents a huge societal cost anyhow. That it also represents considerable mental stress and negative wellbeing among those identified as over-indebted is even more indisputable. 7

In their study on the health effect of individuals’ over-indebtedness conducted on behalf of the Swedish Consumer Agency (SCA), Ahlström and Edström (2014) find that over-indebted individuals are feeling significantly less well (and even “dramatically worse”) with regard to their psychological and emotional wellbeing as well as physiological condition than those who are not. The longer time they have been over-indebted, the worse they feel. The authors could not distinguish any negative relationship between over-indebtedness and wellbeing among those who had just become over-indebted. They conclude that: ‘[t]his shows that over-indebtedness is a complex phenomenon that cannot be explained on the basis of a few variables and that it needs to be studied over time in order to shine light on the effect of over-indebtedness and on the underlying mechanisms’ (ibid.: 11). As previously mentioned in Sect. 2.1, they observe that some over-indebted individuals could even become suicidal. This is when they face penalties in the form of fines and find the situation hopeless as they are unable to see how they can ever get back on their feet again. In particular, women were found to have a greater tendency to enter such mode of thoughts after being approached by debt recovery agencies for recovery of debts.

In a related study, also conducted for SCA, Ahlström , Edström and Savemark (2014) investigate the degree of socioeconomic, physical and mental rehabilitation of a subset of individuals that underwent debt restructuring between 2003 and 2008 in accordance with the then existing Debt Clearance Act (SFS 1994:334). 8 Based on their survey conducted in 2011, the authors report that more than half of the participants in their sample (which was about 13% of the total population of individuals that started to be subject to debt restructuring in 2003) had been over-indebted more than ten years. On the one hand, a majority stated that the support provided by the municipality’s budget and debt counseling service had significantly affected their self-confidence positively (76%) and, in addition, created order in their economic situation (72%), made it possible for them to be able to move on (42%) and even feel better (46%). On the other hand, almost all stated that their over-indebtedness had negatively affected their wellbeing and more than half acknowledged that the strained economic conditions they had been exposed to and lived under for a very long time had also negatively impacted on their family relationships. Three years after being debt-free, some of them even felt worse than when they were over-indebted. Every second participant did not have a job and every fifth was divorced. These results make the authors question whether the debt restructuring had contributed to any rehabilitation at all. The debt restructuring was considered initiated and carried out far too late.

In reality, only a fraction of those individuals that are defined as over-indebted according to the administrative approach are undergoing debt restructuring and most of them are 55 years old or older (Ahlström , 2015; de Toro , 2016). Using statistics from SEA , de Toro (2016) states that approximately a quarter of a million people in Sweden are over-indebted for a longer time than five years. This means that they have one or more arrears registered at SEA, which they have not been able to settle in five years or even longer. In general, arrears are first tried to be recovered by the original creditors, who otherwise engage a debt recovery company to do this for a fee. If being unsuccessful, the debt recovery company often turns to SEA at which the debtor and the amount of arrears are registered. For this, SEA charges a fee. As the fee will be recovered only if the debtor finally becomes able to settle the arrears, the debt recovery company is reluctant to turn to SEA when the debtor is short of assets and regarded as insolvent. This implies that the number of arrears registered at SEA is an underestimation of all outstanding arrears. However, even if the arrears withhold by debt recover companies represent over-indebtedness, the arrears registered at SEA are not necessarily underestimating the total number of over-indebted individuals. It is probably the opposite. One should bear in mind that all arrears at SEA do not represent over-indebtedness according to the administrative approach (and most probably not any of the two other (objective and subjective) approaches either. Many registered arrears are on relatively small amounts and are settled by the debtor. However, the registered arrears at SEA can still provide an indication of how over-indebtedness in Sweden develops over time.

Just recently, SEA started publishing official records of private individuals’ average indebtedness-levels in Sweden. Data are available from 2015 to 2017. The data shows that in 2015, almost 428,000 people in Sweden had an arrear remark at the SEA , with aggregated debts of around €7 billion. This suggests an average debt of approximately SEK 170,000. In 2016, there were around 423,000, also with €7 billion in aggregated debt, and in 2017 there were less than 418,000 but with an aggregated debt of almost €8 billion suggesting an increased average debt to almost SEK 180,000. (The median debt was less than SEK 55,000.) Thus, while the number of individuals reported to SEA has been decreasing, their debt levels have on average increased. Based on these data, Fig. 2 shows the percentage of individuals in each age category.

Young adults are seldom subject to debt restructuring in accordance with Swedish law, but as shown in Fig. 2 also young adults can sometimes have difficulties to meet obligations associated with credit and loan commitments. Clearly, the arrears of young adults (18–25 years) are neither as many nor as sizable as the arrears of other age groups. At the other side of the spectrum, those individuals that are older than 65 years are shown to have almost as few arrears, but the size of their debt represents a significantly larger portion of total outstanding debt.

Further analysis of this data (not shown in Fig. 2) discloses that the distribution between the different age groups remains more or less the same for women and men. Women between 35 and 54 years tend to have a relatively larger portion of the registered total arrears of women in comparison to the correspondent portion of men in the same age group, whereas older men (65+ years) seem to have a relatively greater share of registered arrears than women in that age. Making a direct comparison between men and women, men represented about two-thirds of the population of registered arrears at SEA in all age groups. In each age group, men are also overrepresented when it comes to the debt size of the arrears. Men accounted for 71–80% of total registered arrears debt.

4 Concluding Remarks

Our brief review of academic literature and public government reports in the EU about household indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness, lays a foundation for our research project described in Chapter 1 and in the remainder of the book. The magnitude of the increasing indebtedness of households is manifested and it is also clear that there is limited knowledge about the indebtedness and possible over-indebtedness of young adults, let alone about reasons behind and effects of their excessive debt reliance. The review further clarifies the complexity and many dimensions to consider when assessing and measuring possible over-indebtedness. It is indeed far from trivial to derive a definition of the concept of over-indebtedness that can be easily operationalized in practice and, thus, applicable for identifying over-indebted individuals and households, in general, and young adults, in particular. The typical debt-reliant young adult does not possess sizable assets, but she or he could be expected to have positive net wealth when adopting a theoretical definition. This is in accordance with the life cycle hypothesis, which anticipates increasing disposable income over time for most young adults also in practice. The problem is that some indebted young adults are more exposed to the risk of being trapped and enter into severe financial difficulties. These individuals would be hard to detect even if it were possible to accurately define the concept of over-indebtedness in practice. Some may not be identified as over-indebted at all. In the studies conducted within our research project, we have therefore focused our attention on psychological aspects, and as stated in Chapter 1, with an emphasis on ‘mechanisms that drive the indebtedness of young adults and measures that can be imposed by financial institutions and regulators to encourage more sound borrowing by young adults’.

Notes

- 1.

-

2.

Assuming that expected future cash flows for an asset j occur at the end of each period, and a relevant (risk-weighted) discount rate rj, \(PV_{j} = \sum\nolimits_{t = 1}^{T} {E\left( {CF_{j,t} } \right)\left( {1 + r_{j} } \right)^{ - t} }\) for this asset. Hence, \(MV_{\text{A}} = CF_{0} + \sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{J} {PV_{j} }\).

-

3.

Betti et al. (2007) demonstrate and explain this analytically adopting an economic theoretical framework.

-

4.

Attempts have been made to develop a theoretical model that take uncertainty into account and also covers the (subjective) view and judgement of those indebted. It is more or less inevitable that such a model will be complex. For further discussions and elaborations about difficulties in operationalizing the concept of over-indebtedness, see Betti et al. (2007) and D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013).

-

5.

The authors acknowledge that this threshold of number of loans may not be of relevance any longer considering the increasing availability of various debt products.

-

6.

A cut point of 30% is commonly used. As referred to by D’Alessio and Iezzi (2013) and Oxera (2004) sets 50% as the cut point whereafter debt repayments are becoming burdensome.

-

7.

Ahlström (2015) estimates the total costs to more than SEK 200 billion on an annual basis after also taking into account costs such as health care, production loss, unemployment compensation, long-term sick leave and disability pension.

-

8.

In 2006 and 2016, the Act was replaced with the Debt Clearance Acts: SFS 2006: 548 and, the present, SFS 2016: 675, respectively.

References

Ahlström, R. (2015). Hur stora är samhällskostnaderna för svenska hushålls överskuldsättning med avseende på sjukvårdskostnader, produktionsbortfall, samt ersättningsnivåer i social-försäkringssystemen och A-kassan? In Överskuldsättning – hur fungerar samhällets stöd och insatser? (RiR 2015:14) (bilaga 1). Stockholm: Riksrevisionen.

Ahlström, R., & Edström, S. (2014). Överskuldsättning och ohälsa - En studie av hur långvarig överskuldsättning kan påverka den psykiska- och fysiska hälsan. Konsumentverket (Rapport 2014:16). Available at https://www.konsumentverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/produkter-och-tjanster/bus-och-kvl/rapport-2014-16-overskuldsattning-och-ohalsa-konsumentverket.pdf.

Ahlström, R., Edström, S., & Savemark, M. (2014). Är skuldsanering rehabiliterande? En utvärdering av skuldsanerade personers hälsa, livskvalitet och privatekonomi tre år efter genomförd skuldsanering. Konsumentverket (Rapport 2014:14). Available at https://www.konsumentverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/produkter-och-tjanster/bus-och-kvl/rapport-2014-12-ar-skuldsanering-rehabiliterande-konsumentverket.pdf.

Anderloni, L., & Vandone, D. (2008). Households over-indebtedness in the economic literature (Working Paper, 46, p. 775). Milan: Universit’a degli Studi di Milano.

Betti, G., Dourmashkin, N., Rossi, M., & Ping Yin, Y. (2007). Consumer over-indebtedness in the EU: Measurement and characteristics. Journal of Economic Studies, 34(2), 136–156.

BIS. (2007). Measuring the financial position of the household sector. Proceedings of the IFC Conference, Basel, 30–31 August 2006, Volume 2 IFC Bulletin No 26.

BIS. (2016, December). Statistical Bulletin. Available at https://www.bis.org/statistics/bulletin1612.htm.

Brown, M., Grigsby, J., van der Klaauw, W., Wen, J., & Zafar, B. (2015). Financial education and the debt behavior of the young. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports (Staff Report No. 634).

Caputo, R. K. (2012). Patterns and predictors of debt: A panel study, 1985–2008. The Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 39, 7.

D’Alessio, G., & Iezzi, S. (2013). Household over-indebtedness—Definition and measurement with Italian data (Questioni di Economia e Finanza [Occasional Papers] 149). Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area.

Davydoff, D., Naacke, G., Dessart, E., Jentzsch, N., Figueira, F., Rothemund, M., …, Finney, A. (2008, February). Towards a common operational European definition of over-indebtedness. European Commission. Available at http://www.oee.fr/files/study_overindebtedness_en.pdf.

de Toro, S. (2016). Långvarig överskuldsättning Den bortglömda ojämlikheten. Stockholm: Landsorgani-sationen i Sverige.

Disney, R., Bridges, S., & Gathergood, J. (2008). Drivers of over-indebtedness. Nottingham: Centre for Policy Evaluation, The University of Nottingham.

EC. (2013). Over-indebtedness of European households: Updated mapping of the situation, nature and causes, effects and initiatives for alleviating its impact. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/final-report-on-over-indebtedness-of-european-households-synthesis-of-findings_december2013_en.pdf.

Elliot, V., & Lindblom, T. (2017). The Swedish mortgage market: Bank funding, margins, and risk shifting. In G. Chesini, E. Giaretta, & A. Paltrinieri (Eds.), The business of banking. Palgrave Macmillan studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ferreira, A. (2000). Household over-indebtedness: Report to the economic and social committee. Brussels: European Communities.

Frade, C. (2012). Bankruptcy, stigma and rehabilitation. ERA Forum, 13(1), 45–57.

Gloukoviezoff, G. (2007). From financial exclusion to overindebtedness: The paradox of difficulties for people on low incomes? New frontiers in banking services (pp. 213–245). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Harvey, D. (2010). The enigma of capital and the crisis this time. Atlanta, GA: American Sociological Association Meetings.

Johansson, M. W., & Persson, M. (2007). Swedish households’ indebtedness and ability to pay: A household level study. In BIS. 2007. Measuring the financial position of the household sector. Proceedings of the IFC Conference, Basel, 30–31 August 2006, Volume 2 IFC Bulletin No 26, 234–248.

Kalousova, L., & Burgard, S. A. (2013). Debt and foregone medical care. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(2), 204–220.

Kempson E. (2002, September). Over-indebtedness in Britain: A report to the department of trade and industry. Bristol: Department of Work and Pensions Research.

Kempson, E., McKay, S., & Willitts, M. (2004). Characteristics of families in debt and the nature of indebtedness (Research Report No. 211). Leeds: Corporate Document Services.

Koku, P. S. (2015). Financial exclusion of the poor: A literature review. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(5), 654–668.

Krumer-Nevo, M., Gorodzeisky, A., & Saar-Heiman, Y. (2017). Debt, poverty, and financial exclusion. Journal of Social Work, 17(5), 511–530.

Larsson, S., Svensson, L., & Carlsson, H. (2016). Digital consumption and over-indebtedness among young adults in Sweden (LUii Reports, Vol. 3). Lund: Lund University Internet Institute.

Leyshon, A., & Thrift, N. (1995). Geographies of financial exclusion: Financial abandonment in Britain and the United States. Transaction of the Institute of British Geographers, 20(3), 312–341.

Lombardi, M., Mohanty, M., & Shim, I. (2017). The real effects of household debt in the short and long run (BIS Working Papers No. 607). Monetary and Economic Department.

Modigliani, F. (1966). The life cycle hypothesis of saving, the demand for wealth and the supply of capital. Social Research, 33(2), 160–217.

Orton, M. (2009). The long-term impact of debt advice on low income household (Institute for Employment Research Working Paper). Coventry: University of Warwick. Available at https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2010/orton_2010_long_term_debt.pdf.

Oxera. (2004). Are UK households over-indebted? Commissioned by the Association for Payment Clearing Services (APACS), British Bankers Association (BBA), Consumer Credit Association (CCA) and the Finance and Leasing Association (FLA). Available at https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Are-UK-households-overindebted-1.pdf.

Pleasence, P., & Balmer, N. J. (2007). Changing fortunes: Results from a randomized trial of the offer of debt advice in England and Wales. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 4(3), 651–673.

Raijas, A., Lehtinen, A. R., & Leskinen, J. (2010). Over-indebtedness in the Finnish consumer society. Journal of Consumer Policy, 33(3), 209–223.

Ramsay, I. (2003). Consumer credit society and consumer bankruptcy: Reflections on credit cards and bankruptcy in the informational economy. In J. Niemi-Kiesiläinen, I. Ramsay, & W. Whitford (Eds.), Consumer bankruptcy in global perspective (pp. 17–39). Portland: Hart Publishing.

Ramsay, I. (2012). A tale of two debtors: Responding to the shock of over-indebtedness in France and England—A story from the Trente Piteuses. The Modern Law Review, 75(2), 212–248.

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2013). The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1148–1162.

Riksbank. (2017). Den starka tillväxten i konsumtionslån – drivkrafter och konsekvenser. Available at https://www.riksbank.se/sv/press-och-publicerat/nyheter-och-pressmeddelanden/nyheter/2017/den-starka-tillvaxten-i-konsumtionslan–drivkrafter-och-konsekvenser/.

Rueger, H., Schneider, N. F., Zier, U., Letzel, S., & Muenster, E. (2011). Health risks of separated or divorced over-indebted fathers: Separation from children and financial distress. Social Work in Health Care, 50(3), 242–256.

Schicks, J. (2013). The definition and causes of microfinance over-indebtedness: A customer protection point of view. Oxford Development Studies, 41(1), 95–116.

SEA. (2008). Alla vill göra rätt för sig. Överskuldsättningens orsaker och konsekvenser. Krono-fogden. Available at https://www.kronofogden.se/download/18.44812de6133c5768d6780007930/1371144370107/Slutrapport+Alla+vill+göra+rätt+för+sig+januari+2008.pdf.

SFS (1994:334). Skuldsaneringslag. Available at http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skuldsaneringslag-1994334_sfs-1994-334.

Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 708–723.

SNAO. (2015). Överskuldsättning – hur fungerar samhällets stöd och insatser? (RiR 2015:14). Stockholm: Riksrevisionen.

Stamp, S. (2012). The impact of debt advice as a response to financial difficulties in Ireland. Social Policy and Society, 11(1), 93–104.

Sullivan, T., Warren, E., & Westbrook, J. (2000). The fragile middle class: Americans in debt. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sweet, E., Nandi, A., Adam, E. K., & McDade, T. W. (2013). The high price of debt: Household financial debt and its impact on mental and physical health. Social Science & Medicine, 91, 94–100.

Vandone, D. (2009). From indebtedness to over-Indebtedness. In Consumer credit in Europe (pp. 69–97). Contributions to Economics. Physica-Verlag HD.

Walker, C. (2012). Personal debt, cognitive delinquency and techniques of governmentality: Neoliberal constructions of financial inadequacy in the UK. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 22(6), 533–538.

Yoon, I. (2009). Securing economic justice and sustainability from structural deviances: Recommendations for consumer credit policy changes. Journal of Poverty, 13(1), 40–54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Elliot, V., Lindblom, T. (2019). Indebtedness, Over-Indebtedness and Wellbeing. In: Hauff, J., Gärling, T., Lindblom, T. (eds) Indebtedness in Early Adulthood. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13996-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13996-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-13995-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-13996-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)