Abstract

Occupational identity refers to the conscious awareness of oneself as a worker. The process of occupational identity formation in modern societies can be difficult and stressful. However, establishing a strong, self-chosen, positive, and flexible occupational identity appears to be an important contributor to occupational success, social adaptation, and psychological well-being. Whereas previous research has demonstrated that the strength and clarity of occupational identity are major determinants of career decision-making and psychosocial adjustment, more attention needs to be paid to its structure and contents. We describe the structure of occupational identity using an extended identity status model, which includes the traditional constructs of moratorium and foreclosure, but also differentiates between identity diffusion and identity confusion as well as between static and dynamic identity achievement. Dynamic identity achievement appears to be the most adaptive occupational identity status, whereas confusion may be particularly problematic. We represent the contents of occupational identity via a theoretical taxonomy of general orientations toward work (Job, Social Ladder, Calling, and Career) determined by the prevailing work motivation (extrinsic vs. intrinsic) and preferred career dynamics (stability vs. growth). There is evidence that perception of work as a calling is associated with positive mental health, whereas perception of work as a career can be highly beneficial in terms of occupational success and satisfaction. We conclude that further research is needed on the structure and contents of occupational identity and we note that there is also an urgent need to address the issues of cross-cultural differences and intervention that have not received sufficient attention in previous research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Occupational identity, also alluded to as vocational, work, professional, or career identity, refers to the conscious awareness of oneself as a worker. On the one hand, occupational identity represents one’s perception of occupational interests, abilities, goals, and values (Kielhofner, 2007). On the other hand, occupational identity represents a complex structure of meanings in which the individual links his or her motivation and competencies with acceptable career roles (Meijers, 1998). Occupational identity has frequently been conceptualized as a major component of one’s overall sense of identity (Kroger, 2007; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). From this perspective, it represents a core, integrative element of identity, serving not only as a determinant of occupational choice and attainment, but also as a major factor in the emergence of meaning and structure in individuals’ lives (Erikson, 1968). Although there is no universal agreement regarding the domains of identity that are most relevant, the domain of occupation appears to be a central element of identity (Schwartz, 2001). Over the past 50 years, research on the structure, functions, and development of occupational identity has been conducted by scholars from a variety of disciplines, with the majority of the studies conducted within the field of vocational psychology.

Vocational and developmental psychologists view forming an occupational identity as a critical developmental task of adolescence, and vocational identity formation is taken to represent an overall index of progress in career development (Kroger, 2007; Savickas, 1985; Vondracek, 1995; Zimmer-Gembeck & Mortimer, 2006). Thus, it is not surprising that the concept of occupational identity has been incorporated in almost every major theory of career development (e.g., Bordin, 1984; Holland, 1985; Peatling & Tiedeman, 1977; Super, Savickas, & Super, 1996; Tiedeman & O’Hara, 1963). Nevertheless, only two of these theoretical perspectives on occupational identity continue to be widely utilized. One is a personality-theory-based approach established by Holland (1985), and the other stems from a psychosocial approach based on Erikson’s (1963, 1968) theory of identity.

John Holland, the author of a popular theory about the relationships between personality types and work environments, known as the Person-Environment Fit Theory (1985), added the construct of identity to his theory in the 1970s. Holland’s objective was to use both personality types and subjective awareness of one’s occupational preferences to predict occupational choice and occupational success. He defined occupational identity (vocational identity in his terminology) as a clear, stable, and coherent picture of one’s career goals, interests, and abilities (Holland, 1985; Holland, Daiger, & Power, 1980; Holland, Gottfredson, & Power, 1980). Holland’s definition of occupational identity has been subsequently integrated into another major career theory, Super’s Life-span, Life-space Theory (Super et al., 1996) and stimulated considerable research over the past 30 years.

Although Holland (1985) noted that vocational identity develops during childhood and adolescence through increasing differentiation among preferred activities, interests, competencies, and values, his approach focused on the strength of identity while largely ignoring its structure and the complexity of developmental processes involved in its formation. Holland’s rather simplistic perspective on identity has been criticized by developmentally minded vocational psychologists, particularly because of its inability to differentiate among identity achievement and foreclosure (Brisbin & Savickas, 1994; see also Kroger & Marcia, Chapter 2, this volume) and to capture the differentiation, coherence, and stability (as well as clarity) of occupational self-concept (Vondracek, 1992). Since the 1970s, an alternative approach to the construct of occupational identity, based on Erikson’s ego identity theory (Erikson, 1963, 1968; see Kroger & Marcia, Chapter 2, this volume), has become widely accepted (Blustein & Noumair, 1996; Munley, 1977; Savickas, 1985; Vondracek, 1992). Given that Erikson considered occupational choice and commitment to be the core elements of identity and noted that the inability to settle on an occupation is especially disturbing during the transition to adulthood (Erikson, 1968), his approach has been readily embraced by vocational psychologists.

Erikson described identity as the experience of “wholeness” characterized by a sense of individuality, continuity, and integration of personal goals and values, potentially achieved through the psychosocial crisis of adolescence (Erikson, 1968). According to Erikson, failure to establish a sense of personal identity during adolescence leads to confusion with regard to future adult roles and can be associated with an array of adjustment problems. The dynamic nature and complexity of adult roles in modern societies make the process of identity formation difficult and stressful. Although some individuals can adopt a foreclosed identity based on premature early identification with parents, peers, and other role models, establishing a true sense of identity involves a relatively long period of psychosocial moratorium, characterized by active role experimentation and postponing making adult role commitments. In contrast to Holland’s model, the Eriksonian perspective suggests considerable differences in the consequences of identity commitments characterized by foreclosure versus those characterized by achievement and assumes that the state and strength of occupational identity should be interpreted from the perspective of developmental stages. Thus, during the period of identity moratorium, adolescents may appear to be vocationally maladjusted as they experience an identity crisis, but this period of internal instability is an important developmental precursor for further occupational and psychosocial adaptation (Erikson, 1963, 1968).

The operationalization of occupational identity within the Eriksonian approach has most frequently been guided by Marcia’s (1966) identity status construct (see Kroger & Marcia, Chapter 2, this volume). Identity status refers to a characteristic way of dealing with the salient identity issues characterized by exploration and decision-making crisis on the one hand, and by personal investment and commitment on the other (Marcia, 1966, 1993). Following Marcia, many vocational researchers (e.g., Dellas & Jernigan, 1981; Melgosa, 1987; Munson & Widmer, 1997) have described occupational identity Achievement as a strong commitment to self-chosen occupational goals and values acquired through occupational exploration. In contrast, occupational identity Foreclosure is characterized by occupational commitments made without much occupational- and self-exploration. Occupational identity Moratorium represents an active process of exploration and crisis and temporary inability to make a lasting career commitment. Occupational identity Diffusion is characterized by lack of effective exploration and inability to make commitments, regardless of whether one has already experienced a period of crisis.

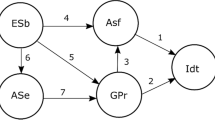

Marcia’s identity status categories have been effectively used in research on occupational identity directly or with minor modifications (e.g., Goossens, 2001; Meeus, Dekovic, & Iedema, 1997; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). There have also been attempts to refine and extend the identity status paradigm (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, Beyers, & Vansteenkiste, 2005; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). Revisions to the original identity status paradigm were suggested, in part, by Marcia’s recognition that some individuals appear to be characterized by fluctuations between moratorium and achievement, which he called the MAMA cycles (Stephen, Fraser, & Marcia, 1992). Individuals in MAMA cycles have made identity commitments, but did not disengage from the process of exploration, which assumes a state of identity characterized by continuously updated, dynamic, and flexible choices rather than a static commitment. Recognition of the importance of differentiating between lack of interest and involvement in exploring identity issues (identity diffusion) and failure to secure a sense of identity despite having completed the process of exploration (identity confusion), described by Erikson as a potentially dangerous role confusion (Erikson, 1963), provided further impetus to expand the identity status paradigm. The resulting expanded model of occupational identity status proposed by Skorikov and Vondracek (2007) is shown in Table 29.1.

Although this expansion of the identity status paradigm is a step in the right direction, it still does not fully capture occupational identity as the complex, evolving structure of meanings in which the individual links his or her motivation and competencies with acceptable career roles (Meijers, 1998; Savickas, 1985; Vondracek, 1992). Accordingly, a recent volume dedicated to occupational identity research in Europe (Brown, Kirpal, & Rauner, 2007) outlined a few important observations about the nature of modern occupational identities:

-

Occupational identity is characterized by both continuity and change

-

Occupational identity is shaped by the changing system of interpersonal relationships around which it is constructed

-

Individuals make a significant contribution to the construction of their occupational identity

-

Individual occupational identities are constrained by social-economic structures and processes (also see Oyserman & James, Chapter 6, this volume)

-

There is considerable variation in the salience of occupational identity within the person’s overall sense of identity

These generalizations are consistent with a recent analysis of occupational identity (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007), which utilized the developmental contextual perspective on career development (Vondracek, Lerner, & Schulenberg, 1986). Skorikov and Vondracek described occupational identity as a dynamic organization of occupational self-perception, shaped by “qualitative and quantitative changes in the structure and form of identification with the role of a worker that occurs as a result of the interaction between the epigenetic unfolding of the person’s capabilities and learning through self-chosen and socially assigned vocational, educational, and leisure activities” (p. 146). Additionally, the process of constructing one’s occupational identity is influenced by relevant significant relationships and broader social factors, such as societal norms and expectations and economic and technological change.

Whereas the structural aspects of occupational identity have been extensively studied at least since the 1980s, its content has received considerably less attention in the literature. The importance of significant differences in occupational identities, and the ways in which these differences are associated with the underlying assumptions about the meaning of work, have been largely ignored in theory and research on careers and on identity (Blustein, 2006). Developing an understanding of occupational identity as a system of meanings associated with the worker role requires attending to its contents as well as its structure. Thus, a distinction between work as a job versus as a career has been re-emphasized in recent European studies, as the “job” perspective appears to be characterized by lack of a long-term perspective and of a sense of uniqueness, along with passive adoption of an ascribed identity. The “career” perspective, on the other hand, is marked by an active construction of occupational identity and focus on long-term career prospects and occupational success from a highly individualized perspective (FAME Consortium, 2007). Other authors have drawn upon a more traditional triad of the meanings of work as a job, as a career, or as a calling (Walsh & Gordon, 2008; Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin, & Schwartz, 1997). However, the rationale for these traditionally utilized groupings has not been clearly articulated. Thus, in an attempt to develop a logically consistent taxonomy of general orientations toward work, Skorikov (2008) suggested a two-dimensional approach. First, an individual’s meaning of work can be described in terms of the relative importance of extrinsic and intrinsic work motivation (see Soenens & Vansteenkiste, Chapter 17, this volume; Waterman, Chapter 16, this volume). Whereas most workers value occupational rewards and conditions as well as the work that they actually do, one is typically more important than the other within the individual’s system of work preferences. Second, from the perspective of career dynamics, the meaning of work may be characterized by orientation toward professional growth versus stability. The corresponding theoretical model is presented in Table 29.2.

An empirical assessment of this logical taxonomy of general orientations toward work indicated that the four categories indeed represent empirically independent types of subjective meanings assigned to work in accord with one’s sense of identity (McKeague, Skorikov, & Serikawa, 2002). Of course, many additional aspects of the contents of identity should be considered to provide a comprehensive description of the range of individual perceptions of work and of one’s role as a worker. Among those, one’s commitment to a particular occupational field as well as work role salience and its relative subjective importance among other life roles are also critical (Brown et al., 2007; Super et al., 1996). We address these issues in the sections that follow.

Occupational Identity and the Overall Identity Structure

As noted above, in accord with Erikson’s theoretical propositions, occupational identity can be considered as a core element of identity (Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). In the modern world, occupation is often viewed not only as the major source of income, but also as the main mechanism of social integration and the means of developing and expressing one’s identity (Christiansen, 1999). Empirical studies confirm that engaging in occupational exploration and making occupational commitments leads not only to establishing a sense of occupational identity, but also to constructing one’s identity in general from childhood through adulthood (Flum & Blustein, 2006; Kroger, 2007; Skorikov, 2007; Vondracek, Silbereisen, Reitzle, & Wiesner, 1999).

Numerous cross-sectional studies have found positive associations between occupational identity and more general conceptions of identity in adolescence and young adulthood (Blustein, Devenis, & Kidney, 1989; Nauta & Kahn, 2007; Savickas, 1985; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). Whereas identity development is often marked by asynchrony and relatively low congruence across different domains (Goossens, 2001; Meeus, Iedema, Helsen, & Vollebergh, 1999; Solomontos-Kountouri & Hurry, 2008), adolescents are more likely to be characterized by identity achievement in the occupational domain than in any other domain (Grotevant & Thorbecke, 1982; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). Skorikov and Vondracek (1998) found that identity development in the domains of lifestyle, ideology, religion, and politics was correlated with, but lagged behind, occupational identity development, and these authors concluded that occupational identity plays the leading role in the process of adolescent identity formation.

The effects of occupational identity on identity in general are likely to be particularly strong during the transition from school to work (Danielsen, Lorem, & Kroger, 2000). During that period, successful employment strengthens the sense of occupational identity and its salience within the overall identity structure, whereas failure to find adequate employment increases the subjective importance of relational identity, which may then replace occupational identity as a main source of meaning and psychological well-being (Meeus et al., 1997; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). Interestingly, in a Norwegian study of recent high-school graduates, work was found to be the primary influence on overall identity regardless of whether the participants were attending college, working, or unemployed (Danielsen et al., 2000). In young and middle adulthood, the relationships between occupational identity and other identity domains become progressively reciprocal as individuals recognize the need to balance their work, family, religious, and other commitments (Dorn, 1992; Friend, 1973; Kroger, 2007). However, there is also evidence that identity development in the occupational domain consistently outpaces development in other domains in adulthood and is most congruent with identity development at the overall level (Fadjukoff, Pulkkinen, & Kokko, 2005).

Functions of Occupational Identity

The formation of an occupational identity is an important career and developmental task of adolescence (Erikson, 1968; Flum & Blustein, 2006; Lapan, 2004; Vondracek et al., 1986). From a career development perspective, occupational identity represents the central mechanism of agentic control over one’s career development (Meijers, 1998; Vondracek & Skorikov, 1997), because it serves as a principal cognitive structure that controls the assimilation and integration of self- and occupational knowledge and allows for making logical and systematic career decisions even when facing a serious career problem. Without a clear and strong occupational identity, individuals would be unable to make self-endorsed career choices, resulting in feelings of distress. This could further impede the capacity for adaptive information processing and decision making (Saunders, Peterson, Sampson, & Reardon, 2000). Indeed, the strength of occupational identity is closely associated with various indices of overall career development progress, such as career maturity (Holland, Johnston, & Asama, 1993; Leong & Morris, 1989; Savickas, 1985; Turner et al., 2006).

Theoretically, possessing an established occupational identity allows for making relatively easy, rational, and mature career decisions in the face of occupational ambiguities (Holland, 1985; Raskin, 1985; Saunders et al., 2000). This proposition has been supported in numerous studies of adolescents and young adults where positive associations have been reported between occupational identity and career decision-making skills, career search and decision-making self-efficacy, career choice readiness, and career decidedness (Gushue, Scanlan, Pantzer, & Clarke, 2006; Hirschi & Läge, 2007; Holland et al., 1993; Solberg, 1998). In contrast, career indecision is correlated with a less established sense of occupational identity (Conneran & Hartman, 1993; Holland & Holland, 1977). Longitudinal studies of occupational identity in adults provide further evidence of its functional importance. For example, occupational identity achievement was found to be a significant predictor of both occupational attainment and re-establishing the worker’s role in the process of occupational rehabilitation (Braveman, Kielhofner, Albrecht, & Helfrich, 2006; Schiller, 1998).

Another important function of occupational identity is to provide the person with a sense of direction and meaning and to establish a framework for occupational goal setting and self-assessment (Christiansen, 1999; Meijers, 1998; Raskin, 1985; Solberg, Close, & Metz, 2002). Experimental research has demonstrated that vocational identity is a strong predictor of the quality of reasoning about future career challenges and opportunities (Klaczynski & Lavallee, 2005). Additionally, naturalistic studies suggest that one’s sense of vocational direction is an important predictor of success during the transition from school to work (Lapan, 2004; Mortimer, Zimmer-Gembeck, Holmes, & Shanahan, 2002), particularly for disadvantaged adolescents (Diemer & Blustein, 2006; Ladany, Melincoff, Constantine, & Love, 1997).

Adult occupational identity incorporates both (a) an understanding of who one has been and (b) a sense of desired and possible directions for one’s future, and it serves as a means of self-definition and a blueprint for future action (Kielhofner, 2007). The organizing role of occupational identity has been consistently supported in research on workers in a variety of occupations. For example, studies have shown that occupational identity is an important predictor of continuity in one’s work role, occupational and organizational commitment, and work performance (Baruch & Cohen, 2007; Kidd & Frances, 2006; Suutari & Makela, 2007). Research also suggests that occupational identity serves as a control mechanism that regulates adult career stability and the range of acceptable career options (King, Burke, & Pemberton, 2005).

Finally, many theorists have argued that possessing a strong occupational identity contributes to psychosocial adjustment, well-being, and life satisfaction (Christiansen, 1999; Kroger, 2007; Raskin, 1985; Vondracek, 1995). Indeed, empirical studies have provided strong and consistent evidence for positive relationships between occupational identity and psychosocial functioning. During the transition from high school to work, occupational identity achievement appears to be predictive of mental health (De Goede, Spruijt, Iedema, & Meeus, 1999; Meeus et al., 1997) and may help to protect against drug use in men (Frank, Jacobson, & Tuer, 1990). In college students, strength of occupational identity was positively associated with life satisfaction and adjustment, and was negatively associated with distress (Leong & Morris, 1989; Lopez, 1989; Strauser, Lustig, Cogdal, & Uruk, 2006). In working adults, the strength of occupational identity was found to be a strong predictor of affective health, manifested in lower levels of depression and anxiety, and life satisfaction even when controlling for the effects of occupational status, income, education, and self-esteem (McKeague et al., 2002; Schiller, 1998; Skorikov, 2008). A number of cross-sectional studies provide converging evidence that perceiving work as a calling can be highly beneficial in terms of adult workers’ psychological health and well-being (Kidder, 2006; Skorikov, 2008; Vaughan & Roberts, 2007; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). Longitudinal research is needed, however, to clarify the nature of these associations and to test causal hypotheses about the role of occupational identity in human lives.

Occupational Identity Development

From a developmental point of view, occupational identity formation represents a lifelong process of constructing, shaping, and reshaping the self as a worker (FAME Consortium, 2007). At any given point in time, occupational identity reflects accumulated life experiences organized into an understanding of who one is and wishes to become (Kielhofner, 2007). Adolescence is often considered the stage of development during which the process of identity formation begins, as the limitations of children’s cognition and activity may not permit establishing complex, integrated, and stable self-representations (Kroger, 2007). However, childhood experiences very likely provide a foundation for one’s occupational identity formation (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007).

Although children’s perceptions of work do not seem to be incorporated into an identity-like cognitive structure (Barak, Feldman, & Noy, 1991; Cook & Simbayi, 1998; Sellers, Satcher, & Comas, 1999), early vocational experiences and preferences may have lasting effects on the process of occupational identity construction. For example, informal observations of family members’ work behavior and attitudes, societal expectations and cultural stereotypes, and mass media gradually shape the individual meaning of work (Danto, 2003), and by middle childhood a relatively stable system of vocational preferences can be established. Under favorable conditions, these preferences can facilitate future occupational identity formation (Vondracek et al., 1999). However, they can also exert negative effects. For instance, early experience of restrictive gender-role stereotypes and confined social class roles can limit the range of exploration and perceived career opportunities in adolescence (Gottfredson, 2005).

It is not uncommon for a child to adopt an occupational identity at a young age as a result of identifying with an adult or accepting an occupational identity assigned by others (Kalil, Levine, & Ziol-Guest, 2005). In that case, the child’s identity would be almost inevitably ascribed and characterized as foreclosed rather than self-chosen and characterized as achieved (Brisbin & Savickas, 1994; Erikson, 1963; Vondracek et al., 1986). Furthermore, early occupational commitments are often based on an unrealistic self-assessment and change quickly during the transition from school to work (Vondracek & Skorikov, 1997). For example, there is evidence that athletic occupational identity formed at a relatively young age can be remarkably stable throughout childhood and adolescence, but is frequently associated with failure to explore alternative occupations, poor career decision-making skills, and low career maturity (Brown, Glastetter-Fender, & Shelton, 2000; Murphy, Petitpas, & Brewer, 1996). Most importantly, such foreclosed identities rarely allow for implementing one’s vocational plans in the world of adult work (Brown et al., 2000). Thus, many identity researchers argue that an early occupational or major educational choice does not provide an optimal context for psychosocial identity development and future adjustment (e.g., Danielsen et al., 2000). Some children, however, may be much more capable of forming realistic ideas about their future work roles than traditionally assumed, and in those cases there may be positive effects of establishing early vocational preferences (that are, however, open to revision) on subsequent identity development (Vondracek et al., 1999).

Occupational identity development during adolescence may be quite variable, with some adolescents remaining identity diffused in the absence of clear expectations in regard to work preparation and positive role models, while others, when pressured to make decisions about their occupational future, quickly accept a foreclosed occupational identity, especially if they strongly identify with their parents (Vondracek et al., 1986). During the high-school years, however, many adolescents begin questioning and reconsidering the work and career attitudes, beliefs, and values held by adult family members (Stead, 1996), a process referred to by Erikson (1968) as an identity crisis. This process typically leads to occupational identity moratorium, characterized by engagement in exploratory behavior that lays the groundwork for making important career decisions, but that is also usually accompanied by a lengthy delay in making occupational commitments (Erikson, 1968). Inability to make progress toward achieving an occupational identity can lead to vocational role confusion and career stagnation, whereas the emergence of self-understanding and acceptance during the period of moratorium facilitates subsequent occupational identity achievement and helps to promote occupational adjustment (Salomone & Mangicaro, 1991).

Empirical studies have demonstrated that developmental changes in occupational identity cannot be detected over short periods of time and that there is no predictable pattern of change in any given individual’s occupational identity status (Dellas & Jernigan, 1987; Meeus & Dekovic, 1995; Meeus et al., 1999; Van Hoof, 1999). Nevertheless, over longer periods of time, there is a clear developmental progression in occupational identity toward identity achievement and a decline in occupational identity diffusion during adolescence and adulthood (Fadjukoff et al., 2005; Pulkkinen & Kokko, 2000; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). A possible exception to this pattern is represented by occupationally foreclosed adolescents, who are most likely to retain their status, frequently well into adulthood (Dellas & Jernigan, 1987; Fadjukoff et al., 2005).

The period of occupational identity moratorium can be a long and difficult part of late adolescence and young adulthood, especially because many adolescents do not exhibit much progress in career development during high school (Vondracek & Skorikov, 1997). Research on career and identity development during the transition to adulthood consistently suggests that today’s adolescents and young adults around the world have considerable, long-lasting difficulties with formulating career goals and making occupational commitments (Bloor & Brook, 1993; Fadjukoff et al., 2005; Mortimer et al., 2002; Skorikov, 2007). Identity development in the occupational domain is expected to be particularly difficult and stressful (Erikson, 1968). The extent to which young adults benefit from extending the period of occupational moratorium into their late 20s and early 30s may depend on how they approach the processes of individualization and identity formation. Recent research has suggested that young adults who approach these processes proactively and with a strong sense of agency (i.e., they accept responsibility for the course of their life; they own their decisions and accept the consequences; they are confident that they can overcome barriers and obstacles) are more likely to engage in exploration and make flexible commitments and less likely to be conforming and avoiding (Schwartz, Côté, & Arnett, 2005).

Some longitudinal data suggest that postponing a transition to the adult work roles can facilitate further occupational identity development toward identity achievement (Fadjukoff, Kokko, & Pulkkinen, 2007). These findings dovetail with theorizing about the developmental relevance of a long period of occupational identity moratorium, which allows for exploring oneself and one’s career options without making definitive decisions about one’s occupational future (Ladany et al., 1997). However, many young people seem to postpone making occupational commitments without engaging in active and systematic career exploration (Côté, 2000; Salomone & Mangicaro, 1991). Their pattern of occupational behavior, described as floundering (Super, 1957), is marked by an apparently meaningless succession of random jobs and lack of progress in their occupational identity (Mortimer et al., 2002). Floundering is likely to be caused by a diffused identity, which prevents adolescents from making meaningful occupational decisions and from learning from their experiences (Salomone & Mangicaro, 1991). Thus, developing at least a general sense of direction and a tentative occupational identity by the beginning of the transition from school to work is an important conclusion to the process of occupational identity formation throughout childhood and adolescence.

There has been very little research on the developmental trends in occupational identity in adulthood. What is known, however, is that from young to middle adulthood there is a strong trend toward making occupational commitments, but the end result can be identity foreclosure as well as achievement (Fadjukoff et al., 2005; Pulkkinen & Kokko, 2000). This finding is consistent with the results of cross-sectional research, which shows that in working adults the strength of occupational identity is positively correlated with age (Skorikov, 2008). Interestingly, the growth of an occupational commitment also increases the salience of the work role within the person’s overall identity structure (Pulkkinen & Kokko, 2000). Unfortunately, little is known about the role of adult work experience in the construction and reconstruction of occupational identities (Brown et al., 2007). Although positive work experience promotes occupational identity development through strengthening of occupational commitments (e.g., Fagerberg & Kihlgren, 2002), adults must constantly renegotiate the balance between their occupational and life dreams and aspirations and the realities of the job market (Lips-Wiersma & McMorland, 2006). Inability to successfully implement one’s occupational identity due to the limitations imposed by personal and contextual factors can lead to regressive shifts in occupational identity and even to identity loss (Brown et al., 2007; Fadjukoff et al., 2005; Vrkljan & Polgar, 2007). Moreover, in the process of work transitions, employment experience and occupational identity are likely to exert strong, reciprocal effects, but the exact nature of their influences on each other in adulthood has not been systematically studied.

Influences on Occupational Identity Formation

Theoretically, occupational identity development is shaped by the person’s activities and experiences and a variety of individual (e.g., personality and gender) and contextual (e.g., family, peer group, social and economic conditions) factors, as well as their interaction (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). Contextual factors can have direct effects on identity via social stereotypes, modeling, perceived opportunity structure, and environmental constraints (see Oyserman & James, Chapter 6, this volume). At the same time, contextual variables can exert indirect effects on identity formation by regulating the direction and repertoire of individual actions.

Individual Activities and Experiences

Vondracek et al. (1986) argued that both vocational and avocational activities can serve as the means of self- and occupational exploration throughout the lifespan and thus can contribute to the process of occupational identity development. Indeed, Vondracek and Skorikov (1997) found that middle- and high-school students derive ideas about their occupational interests, aspirations, and abilities from a variety of work, school, and leisure activities and do not seem to differentiate among those as sources of their preferences and self-assessment. Participation in various organized youth activities, particularly service, faith-based, community, and vocational activities, has also been found to be a positive factor in shaping adolescent identity (Hansen, Larson, & Dworkin, 2003; Vondracek, 1994).

The role of early work experience in the process of occupational identity development has received increasing attention (e.g., Bynner, 1998; Mortimer, 2003; Mortimer & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1997). However, the actual work activities of children and even adolescents may have limited implications for developing ideas about one’s occupational future and testing one’s capacity to perform adult work roles. First, many cultures discourage formal employment until the completion of mandatory schooling (Ferreira, Santos, Fonseca, & Haase, 2007). Second, even in countries where many adolescents work while attending school, such as the United States, their jobs are typically located within unskilled manual labor and service occupations. These jobs are not perceived by young workers as relevant to their career plans as adults and do not provide significant opportunities for occupational exploration (Arnett, 2000; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1997). Nevertheless, adolescent work experience was found to be positively related to occupational goal setting (Zimmer-Gembeck & Mortimer, 2006) and development of the work value system (Porfeli, 2007; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1997). Early work experience can also have an indirect, delayed effect on occupational identity during the transition from school to work by increasing youths’ employability and potential for securing higher quality jobs (Mortimer et al., 2002). In contrast, youth unemployment and poor quality of the work environment during the transition to adulthood can inhibit the development of occupational identity (Danielsen et al., 2000; De Goede et al., 1999; Peregoy & Schliebner, 1990).

Children and adolescents in most parts of the world spend much of their waking time participating in educational activities. Schooling is a significant determinant of occupational identity formation, because it facilitates the acquisition of work skills, contributes to the development of occupational interests, and provides direct and indirect career guidance (Bynner, 1998; Dellas & Gaier, 1975; Vondracek & Skorikov, 1997). However, little research has been conducted on the specific effects of schools and academic activities on occupational identity, and the results of the few available studies have been inconsistent. For example, Meeus (1993) and Vondracek (1994) found that academic achievement facilitates occupational identity development in adolescence, but other studies did not find significant associations between academic achievement and occupational identity (Penick & Jepsen, 1992; Turner et al., 2006). Considerable variation among school systems makes it difficult to generalize any conclusions about the effects of educational contexts and activities on student occupational identity. There is converging, international evidence, however, that incorporating an occupational perspective in the academic curriculum (via magnet schools with special curricula that attract students from beyond the usual boundaries of school districts, similar to “special schools” in Great Britain, apprenticeships, internships, job shadowing for high-school students that involves following a member of an occupation for a day or longer to observe their activities, etc.,) promotes occupational identity development (Flaxman, Guerrero, & Gretchen, 1999; Heinz, Kelle, Witzel, & Zinn, 1998; Remer, O’Neill, & Gohs, 1984; Zimmer-Gembeck & Mortimer, 2006). In contrast, purely academic school systems may delay the process of occupational identity formation by depriving students of opportunities to engage in occupationally relevant exploratory activities (Vondracek & Skorikov, 1997). Apprenticeships seem to be particularly beneficial in terms of promoting occupational identity development (Hamilton, 1990; Zimmer-Gembeck & Mortimer, 2006). However, their success depends on the student’s ability to integrate complementary as well as contradictory learning experiences (Harris, Simons, Willis, & Carden, 2003). Thus, adolescents who have already formed at least some sense of identity are likely to benefit most from apprenticeships (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007).

Extracurricular and leisure activities can have numerous and varied effects on identity development as well (Hansen et al., 2003). High-school students who were more advanced in their occupational identity development were also more likely to be involved in extracurricular activities and sports (Vondracek, 1994). Similar findings were obtained in studies of college students (Munson & Savickas, 1999; Munson & Widmer, 1997). However, existing correlational studies do not preclude the possibility of the reverse effect: engaging in specific types of extracurricular and leisure activities can be an outcome of occupational identity development rather than its cause. For example, volunteerism and sports participation are frequently used by career-concerned high-school students to increase their chances of admission to elite colleges.

Personality

Erikson’s (1963) theory suggests that successful identity formation during adolescence depends on stable, trait-like, adaptive ego qualities, such as optimism, autonomy, and sense of agency and industry, acquired in the process of accomplishing the developmental tasks of childhood. These ego qualities can be seen as personality traits evolving through life experiences on the basis of innate, temperamental characteristics. Thus, as a major component of overall identity, occupational identity formation is expected to be affected by personality. Indeed, studies on middle school, high school, and college students have consistently found positive associations between occupational identity development and adaptive personality characteristics (e.g., openness to new experiences, flexibility, curiosity) and negative associations between occupational identity and self-defeating traits (e.g., narcissism, rigidity, defensiveness). In adolescence and young adulthood, occupational identity strength and occupational identity achievement are positively correlated with self-esteem (Munson, 1992; Santos, 2003), proactivity and goal directedness (Santos, 2003; Turner et al., 2006), self-regulation, internal locus of control and orientation toward personal growth (Robitschek & Cook, 1999), and rational decision making (Saunders et al., 2000). In contrast, occupational identity is negatively correlated with general indecisiveness (Lucas & Epperson, 1990; Santos, 2001), goal instability (Santos, 2003), and trait anxiety and depression (Lopez, 1989; Saunders et al., 2000). Unfortunately, there have been no longitudinal studies on the relationships between personality traits and occupational identity, and the hypothesized direction of effects has not been tested.

Gender

Historically, sex-related differences have frequently been theorized to be a major influence on identity in general and on occupational identity in particular (Erikson, 1968; Josselson, 1987). However, numerous empirical studies conducted on early, middle, and late adolescent samples in different countries over the past 20 years have found few or no gender differences in the process of occupational identity formation and its outcomes (Archer, 1989; Diemer & Blustein, 2006; Munson, 1992; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998). Some studies indicate that girls can be somewhat more advanced than boys in their occupational exploration and commitment during middle and late adolescence (Meeus & Dekovic, 1995; Skorikov & Vondracek, 1998), which may be partially explained by the developmental lag in pubertal and maturational processes during adolescence in boys compared with girls (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007).

In an early study by Grotevant and Thorbecke (1982), occupational identity was positively related to masculinity in both male and female high-school students. Studies on young adults suggest, however, that gender-related differences in societal demands and expectations may actually promote occupational identity formation in women. For example, Savickas (1985) found that, among medical school students, young adult women were more committed to their career goals, more likely to explore their career options, and had better-defined occupational identities compared to their male counterparts. Savickas explained his findings in terms of the women’s need to possess a more stable occupational identity in order to choose and enter a male-dominated occupation. This explanation was supported in a study of Belgian college students majoring in engineering and psychology, in which women were much more likely than men to be assigned to the occupational identity achievement status (Goossens, 2001).

For modern women, the need to progress toward occupational identity achievement can represent a general, rather than occupation-specific, demand. As adolescent girls move into adulthood, contemporary societal expectations promote multiple role conflicts within the female identity (Barnett & Hyde, 2001), but studies of adult women suggest that employment is now the most important role in the hierarchy of role identities for the majority of women (Graham, Sorell, & Montgomery, 2004). To cope with various role conflicts, a working woman needs to possess a clear picture of herself as a worker – and this portrayal must be well integrated into her overall identity. In light of the above, it may not be surprising that, in a long-term study of identity development in Finland (Fadjukoff et al., 2005), women were found to clearly outpace men in terms of progress toward occupational identity achievement from young through middle adulthood. By the age of 42, almost 70% of women in the Finnish sample were identity achieved in the occupational domain, compared to just over 50% of men. In contrast, men were twice as likely to experience regressive changes (transitions in the direction opposite to the hypothesized progressive sequence, which moves from identity diffusion to foreclosure to moratorium to achievement) in their occupational identity compared to women – 37% versus 19%. Whereas both men and women showed a strong tendency to make occupational commitments, as they grew older, men were more likely than women to adopt a foreclosed identity.

Despite similarities in the level of occupational identity development in adolescence, there are considerable gender differences in the relationships of occupational identity with other domains of identity (Goossens, 2001). Adolescent girls may be more advanced than boys in the family role domain of their identities (Archer, 1989) and may consider their relational identity more important than their occupational identity (Meeus & Dekovic, 1995). The occupational identity of high-school boys appears to be separated from the issues of gender and family, whereas in female high-school students, gender identity begins playing a central role in perceived occupational interests and abilities (Hollinger, 1988). In the process of negotiating their identities, girls begin balancing the occupational and other domains of identity earlier than boys and become progressively sensitive to the issues of family and relationships when making educational and occupational choices in late adolescence (Vondracek et al., 1986). By the end of adolescence, career commitment appears to be negatively related to intimacy (Seginer & Noyman, 2005), and some young women may change their previous occupational plans in favor of their family plans, whereas many professional women decide not to have children in order to pursue their careers. However, the distinction between the occupational and family domains of identity in women has been contested in the literature. Thus, Merrick (1995) argued that adolescent childbearing in some instances can be regarded as a career choice through which young women implement their sense of identity and which represents their adult occupation. Indeed, in some studies of occupational identity, motherhood and child rearing were considered an occupational choice for women (e.g., Frank et al., 1990).

Gender differences and similarities observed in research on occupational identity certainly depend on the historic trends in the interpretation of gender roles and cultural norms given that social context is a strong determinant of occupational identity salience, as well as of the relative importance of different identity domains (Shorter-Gooden & Washington, 1996; Solomontos-Kountouri & Hurry, 2008; Stead, 1996). To date, most research on gender issues in occupational identity has been conducted in Europe and North America, and findings cannot be generalized to other social and historical contexts. In fact, even among post-industrial societies, there is considerable variation in the relationships among various domains of identity (Solomontos-Kountouri & Hurry, 2008). A South African study of the perceived relevance of identity domains in adolescence (Alberts, Mbalo, & Ackermann, 2003) provides an interesting example of such cultural differences. In that study, adolescent girls were more likely than boys to see their future career as very important, whereas relationships with the opposite sex were surprisingly more important for boys than girls.

Family and Peers

The influence of significant others has always been considered a major factor in the process of identity development in general (Danielsen et al., 2000) and occupational identity in particular (Vondracek et al., 1986). Research on children and adolescents suggests that significant figures in their lives, such as parents, friends, and teachers, exert a major impact on their occupational identity (Mortimer et al., 2002). However, these effects are complex and depend on the nature of the underlying interpersonal relationships (Li & Kerpelman, 2007) and the entire pattern of social interactions (Flaxman et al., 1999). For example, the density of the social network that provides mentoring is – surprisingly – negatively related to the clarity of occupational identity during the transition from college to work (Dobrow & Higgins, 2005). A possible explanation is that increasing the breadth, rather than depth, of exploration does not immediately promote career planning and decision making, but rather intensifies the experience of an occupational identity moratorium (Porfeli & Skorikov, 2010; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Rodriguez, 2009).

Family of origin is considered a key factor in child and adolescent career development in general (e.g., Bryant, Zvonkovic, & Reynolds, 2006; Hartung, Porfeli, & Vondracek, 2005; Vondracek et al., 1986). However, empirical research on the effects of family on occupational identity formation has been largely inconclusive. For example, Lopez (1989) reported that the overall strength of occupational identity was correlated with family dynamics (i.e., how family members relate to one another), whereas others (e.g., Hartung, Lewis, May, & Niles, 2002) have not found a significant association. Moreover, when the associations among family variables are statistically controlled, very few characteristics of the family exert independent effects on occupational identity (Hargrove, Creagh, & Burgess, 2002; Johnson, Buboltz, & Nichols, 1999). Hargrove, Inman, and Crane (2005) found no association between strength of high-school students’ occupational identity and any of the family environment characteristics studied, including quality of family relationships, family goal orientations, and degree of organization and control within the family system. In a study of 11th graders, Penick and Jepsen (1992) found that the strength of occupational identity was also independent of the family’s socioeconomic status, and that there was no consistent pattern of associations with family characteristics reported by students, mothers, and fathers. Similarly, a large-scale study conducted on 12–24-year-old Dutch adolescents found that the effects of family on occupational identity status were small, and that the process of occupational identity formation appeared to be influenced more strongly by peers than parents (Meeus & Dekovic, 1995). Similar findings were reported in a study of commitment to career choice among American college students (Feldsman & Blustein, 1999). In contrast, Berríos-Allison (2005) reported more consistent associations between occupational identity status and family differentiation, connectedness, and separateness.

The influence of peers on occupational identity may be particularly strong in middle adolescence, when membership in adolescent crowds is predictive of occupational interests and preferences in early adulthood (Johnson, 1987). Meeus (1993) found that support provided by high-school friends facilitated progress toward occupational identity achievement, and that the effects of peers remained consistently important in educational and work settings after high school graduation (see also Meeus & Dekovic, 1995). The influence of peers on adolescent occupational identity has been interpreted in terms of mutual reinforcement within the peer group, which is typically characterized by similar occupational interests and career goals (Flaxman et al., 1999).

Nevertheless, family should not automatically be considered less important than peers in terms of effects on occupational identity development (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). First, the formation of a peer group and peer interactions are undoubtedly influenced by upbringing in the family (e.g., Granic, Dishion, & Hollenstein, 2003). Second, the effects of family can be lagged and indirect, and there is evidence that families that promote exploration, independence, and achievement facilitate long-term progress in the process of occupational identity formation, whereas growing up in a dysfunctional family can jeopardize forming an adaptive occupational identity. In contrast, the immediate effects of family can be limited to only some of the occupational identity prerequisites, such as occupational exploration (Flum & Blustein, 2006). Clearly, the effects of family on vocational development are complex and determined by multivariate relationships rather than by simple associations.

Modern Social and Economic Conditions

Occupational identity, as well as identity in general, can be viewed as a form of adaptation to the social context (Baumeister & Muraven, 1996; Kielhofner, 2007), which is effective only in relation to the changing social, economic, and cultural contexts of human lives (Blustein & Noumair, 1996; Law, Meijers, & Wijers, 2002). In the past, many traditional societies assigned an occupational identity to the child based on the basis of cultural norms and traditions, and some cultures may still promote early acceptance of a foreclosed, ascribed identity (Waterman, 1999). However, assigning an occupational identity may not be possible – or at least effective – in modern, post-industrial societies, which encourage active identity exploration and facilitate construction of a highly individualized sense of identity (Kroger, 2007). The growing trend toward individualization of the life course and increased variability in the nature and timing of developmental transitions leaves young people with few normative resources with which to develop a clear occupational identity (Côté, 2000; Mortimer et al., 2002).

Ongoing changes in the world of work have important implications for understanding the current context for occupational identity formation and implementation. Those changes include globalization, rapid shifts in occupational structures and the labor market, continuous technological innovation and lifelong learning, a growing demand for flexibility and mobility at work, a dramatic decrease in loyalty within employee-employer relationships, coupled with a decrease in the availability of normative, predictable, long-term career paths, as well as growing diversity in the workplace (Blustein, 2006; Hall, 2002; Kirpal, 2004; Patton & McMahon, 2006; also see Haslam & Ellemers, Chapter 30, this volume). In Europe, Australia, and North America, these changes have already resulted in the recognition of the growing importance of self-centered, flexible, and proactive careers (Briscoe & Hall, 2006; Brown et al., 2007; Kirpal, 2004; Patton & McMahon, 2006). Accordingly, adjustment to the nature of careers in modern economies progressively depends on establishing and maintaining a strong sense of proactive, dynamic, and highly individualized occupational identity (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). For workers with a traditional, rigid occupational identity, characterized by a high level of identification with a narrowly defined occupation and expectations of loyalty and stability in employer-employee relationships, changes at work present a great challenge (Kirpal, 2004).

Forming an adaptive occupational identity is both important and challenging during the transition to adulthood. Traditionally, following in parents’ footsteps has been the common path toward forming an occupational identity and a major mechanism of the intergenerational transmission of occupational status as well as career advancement (Kalil et al., 2005). However, due to vast and rapid changes in social and economic conditions, educational requirements, and career patterns over the past three decades, children can no longer rely on their parents as adequate career role models. Their career success and satisfaction depend on developing a highly individualized occupational identity characterized by dynamic achievement, but they are offered few opportunities to engage in adequate career exploration and preparation. Furthermore, as adults, they are progressively challenged by massive layoffs, organizational restructuring, and dramatic shifts in the nature of jobs in many occupations in response to technological innovations. Often, individuals are forced to change careers in their 40s or 50s as a result of outsourcing, downsizing, and other corporate decisions. Recent publications make a strong case in favor of the critical role played by the worker’s occupational identity in these career transitions (Fouad & Bynner, 2008). Whereas possessing a strong yet flexible occupational identity has been shown to be particularly important in high-status occupations (Kidd & Frances, 2006; Suutari & Makela, 2007), future research needs to investigate the forms of occupational identity and their implications among lower-status workers, particularly those in non-professional, blue-collar occupations. Some studies suggest that occupational identity could be one of the major factors promoting employability following a job loss among members of those occupations (McArdle, Waters, Briscoe, & Hall, 2007).

Another important line of future research involves a detailed examination of cultural differences and similarities in occupational identity (Blustein & Noumair, 1996; Flum & Blustein, 2006; Toporek & Pope-Davis, 2001). Modern societies are becoming progressively multiethnic and multicultural (see Jensen, Arnett, & McKenzie, Chapter 13, this volume; Huynh, Nguyen, & Benet-Martínez, Chapter 35, this volume), and greater attention should be paid to the cultural and socioeconomic aspects of the meaning of work and of occupational identity construction in ethnic and cultural minority groups. However, only a few empirical studies have addressed the issues of ethnic differences and minority status in occupational identity (e.g., Diemer & Blustein, 2006; Gushue et al., 2006; Leong, 1991; Turner et al., 2006). Although there has been a promising increase in the number of such publications in the past few years, the overall scope of this line of research has been limited. Nevertheless, recent findings clearly demonstrate that developing a strong, positive, and flexible occupational identity is very important for economically disadvantaged and minority youth, who face significant career barriers associated with their status within the society (Diemer & Blustein, 2006, 2007; also see Oyserman & James, Chapter 6, this volume).

In addition, little is known about the functions of occupational identity and its relationships with other domains of identity in non-Western cultural contexts (Fouad & Bynner, 2008). However, the few available studies suggest that the process of vocational identity development in less individualistic, less industrialized, and more religiously based cultures may differ from that observed in the North American and Western European samples that comprise most of the literature (e.g., Solomontos-Kountouri & Hurry, 2008). Further research on international labor force migration, which is frequently associated with renegotiating an occupational identity in the process of occupational and social adaptation (Cooke, 2007), is also urgently needed.

Occupational Identity Interventions

There has been little research on targeted interventions in the process of occupational identity development and their effects on career and life trajectories. Both identity and career theorists have frequently noted the importance of vocational guidance (e.g., Erikson, 1968; Raskin, 1989; Vondracek, 1993) but the evidence suggests that few adolescents obtain any professional help with finding appealing career paths or developing their occupational identities (Mortimer et al., 2002). To successfully promote the process of occupational identity development, interventions should take into account developmental differences in occupational identity formation and status (Raskin, 1994). Such interventions might begin in childhood by helping children to acquire a sense of industry (Vondracek, 1993) and exposing them to positive occupational role models. In adolescence, occupational identity interventions are particularly appropriate, as there is evidence that they may significantly enhance career exploration opportunities and facilitate active and systematic exploration guided by a tentative career choice (Raskin, 1989; Salomone & Mangicaro, 1991). The impact of such interventions can be particularly positive if they include active involvement and support of the family (Berríos-Allison, 2005).

During middle and late adolescence, occupational identity formation can be significantly enhanced by providing career mentors and establishing apprenticeships (Hamilton, 1990; Long, Sowa, & Niles, 1995). In late adolescence, with the emergence of serious concerns about one’s career prospects, even simple, short-term interventions, such as career development courses, have been found to be valuable in terms of motivating adolescents to explore identity issues and clarify their sense of occupational identity (Anderson, 1995; Barnes & Herr, 1998; Scott & Ciani, 2008). Modern interventions with adolescents should also incorporate the use of the Internet, which has already become a powerful tool in the process of occupational identity construction, and should facilitate establishing a relatively flexible occupational identity, necessary for adjustment and success in the labor market (Terêncio & Soares, 2003).

During the transition to adulthood, an important task is assisting youth with the process of integrating the occupational domain with other domains of identity, particularly the family domain (Dorn, 1992; Graham et al., 2004; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007). Yet the most critical task is assisting youth with a successful transition from occupational identity exploration to occupational identity implementation. This transition can be challenging – research suggests that many adolescents do not possess a realistic picture of their occupational opportunities and prospects (Mortimer et al., 2002), and they are further handicapped by insufficient skills and environmental constraints during the transition to the role of an adult worker (FAME Consortium, 2007). As career paths become more changeable and work transitions become more common, there is a growing need to address the corresponding changes and adjustments in occupational identity during middle adulthood (Fouad & Bynner, 2008). One of the key issues for appropriate occupational identity interventions is facilitating adaptability and flexibility. Numerous studies indicate that a narrow and rigid occupational identity is often a major obstacle for occupational success and satisfaction in the modern economy (Brown et al., 2007).

Successful future interventions require a much deeper understanding of occupational identity than has been achieved so far. Clearly, further longitudinal studies are needed to identify the mechanisms underlying occupational identity formation and its outcomes, particularly during the transition to adulthood. Previous research, for the most part, has been conducted on college students and has utilized cross-sectional designs. Findings from such studies provide little information about the nature of the relationships of occupational identity to other aspects of career development and to other identity domains, or about the developmental processes underlying the formation of occupational identity. A systematic investigation of the roles played by schools and family in constructing occupational identities is a critical direction for future research. In this regard, intervention studies could also provide a valuable tool in developing a better understanding of the development and implementation of occupational identity. A careful assessment of intervention outcomes can shed light on the mechanisms of promoting an adaptive identity, as well as on those factors that can jeopardize the progression toward successful identity achievement and implementation. A serious commitment on the part of intervention professionals to understand and deal with the full complexity of individuals trying to develop a firm occupational identity in challenging contexts would benefit not only these individuals but also their families and communities.

References

Alberts, C., Mbalo, N. F., & Ackermann, C. J. (2003). Adolescents’ perceptions of the relevance of domains of identity formation: A South African cross-cultural study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 169–184.

Anderson, K. J. (1995). The use of a structured career development group to increase career identity: An exploratory study. Journal of Career Development, 21, 279–291.

Archer, S. L. (1989). Gender differences in identity development: Issues of process, domain and timing. Journal of Adolescence, 12, 117–138.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Barak, A., Feldman, S., & Noy, A. (1991). Traditionality of children’s interests as related to their parents’ gender stereotypes and traditionality of occupations. Sex Roles, 24, 511–524.

Barnes, J. A., & Herr, E. L. (1998). The effects of interventions on career progress. Journal of Career Development, 24, 179–193.

Barnett, R. C., & Hyde, J. S. (2001). Women, men, work and family. American Psychologist, 56, 781–796.

Baruch, Y., & Cohen, A. (2007). The dynamics between organizational commitment and professional identity formation at work. In A. Brown, S. Kirpal, & F. Rauner (Eds.), Identities at work (pp. 241–260). Dordrecht: Springer.

Baumeister, R. F., & Muraven, M. (1996). Identity as adaptation to social cultural and historical context. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 405–416.

Berríos-Allison, A. C. (2005). Family influences on college students’ occupational identity. Journal of Career Assessment, 13, 233–247.

Bloor, D., & Brook, J. (1993). Career development of students pursuing higher education. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 28, 57–68.

Blustein, D. L. (2006). The psychology of working. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Blustein, D. L., Devenis, L. E., & Kidney, B. A. (1989). Relationship between the identity formation process and career development. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 196–202.

Blustein, D. L., & Noumair, D. A. (1996). Self and identity in career development: Implications for theory and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74, 433–441.

Bordin, E. S. (1984). Psychodynamic model of career choice and satisfaction. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (pp. 94–136). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Braveman, B., Kielhofner, G., Albrecht, G., & Helfrich, C. (2006). Occupational identity, occupational competence and occupational settings (environment): Influences on return to work in men living with HIV/AIDS. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 27, 267–276.

Brisbin, L. A., & Savickas, M. L. (1994). Career indecision scales do not measure foreclosure. Journal of Career Assessment, 2, 352–363.

Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 4–18.

Brown, C., Glastetter-Fender, C., & Shelton, M. (2000). Psychosocial identity and career control in college student-athletes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 53–62.

Brown, A., Kirpal, S., & Rauner, F. (Eds.) (2007). Identities at work. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bryant, B. K., Zvonkovic, A. M., & Reynolds, P. (2006). Parenting in relation to child and adolescent vocational development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 149–175.

Bynner, J. (1998). Education and family components of identity in the transition from school to work. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22, 29–53.

Christiansen, C. H. (1999). Defining lives: Occupation as identity: An essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 547–558.

Conneran, J. M., & Hartman, B. W. (1993). The concurrent validity of the self directed search in identifying chronic career indecision among vocational education students. Journal of Career Development, 19, 197–208.

Cook, J., & Simbayi, L. C. (1998). The effects of gender and sex role identity on occupational sex role stereotypes held by white South African high school pupils. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 53, 274–280.

Cooke, F. E. (2007). ‘Husband’s career first’: Renegotiating career and family commitment among migrant Chinese academic couples in Britain. Work, Employment and Society., 21, 47–65.

Côté, J. E. (2000). Arrested adulthood: The changing nature of maturity and identity. New York: New York University Press.

Danielsen, L. M., Lorem, A. E., & Kroger, J. (2000). The impact of social context on the identity-formation process of Norwegian late adolescents. Youth & Society, 31, 332–362.

Danto, E. (2003). Americans at work: A developmental approach. In D. P. Moxley & J. R. Finch (Eds.), Sourcebook of rehabilitation and mental health practice (pp. 11–26). New York: Kluwer.

De Goede, M., Spruijt, E., Iedema, J., & Meeus, W. (1999). How do vocational and relationship stressors and identity formation affect adolescent mental health? Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 14–20.

Dellas, M., & Gaier, E. L. (1975). The self and adolescent identity in women: Options and implications. Adolescence, 10, 399–407.

Dellas, M., & Jernigan, L. P. (1981). Development of an objective instrument to measure identity status in terms of occupation crisis and commitment. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 41, 1039–1050.

Dellas, M., & Jernigan, L. P. (1987). Occupational identity status development, gender comparisons, and internal-external control in first-year air force cadets. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 587–600.

Diemer, M. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2006). Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 220–232.

Diemer, M. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2007). Vocational hope and vocational identity: Urban adolescents career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 15, 98–118.

Dobrow, S. R., & Higgins, M. C. (2005). Developmental networks and professional identity: A longitudinal study. Career Development International, 10, 567–583.

Dorn, F. J. (1992). Occupational wellness: The integration of career identity and personal identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 176–178.

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fadjukoff, P., Kokko, K., & Pulkkinen, L. (2007). Implications of timing of entering adulthood for identity achievement. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 504–530.

Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2005). Identity processes in adulthood: Diverging domains. Identity, 5, 1–20.

Fagerberg, I., & Kihlgren, M. (2002). Experiencing a nurse identity: The meaning of identity to Swedish registered nurses 2 years after graduation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34, 137–145.

FAME Consortium. (2007). Vocational identity in theory and empirical research: Decomposing and recomposing occupational identities – a survey of theoretical concepts. In A. Brown, S. Kirpal, & F. Rauner (Eds.), Identities at work (pp. 13–44). Dordrecht: Springer.

Feldsman, D. E., & Blustein, D. L. (1999). The role of peer relatedness in late adolescent career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 279–295.

Ferreira, J. A., Santos, E. J. R., Fonseca, A. C., & Haase, R. F. (2007). Early predictors of career development: A 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 61–77.

Flaxman, E., Guerrero, A., & Gretchen, D. (1999). Career development effects of career magnets versus comprehensive schools. Berkeley, CA: National Center for Research in Vocational Education.

Flum, H., & Blustein, D. L. (2006). Reinvigorating the study of vocational exploration: A framework for research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 380–404.

Fouad, N. A., & Bynner, J. (2008). Work transitions. American Psychologist, 63, 241–251.

Frank, S. J., Jacobson, S., & Tuer, M. (1990). Psychological predictors of young adults’ drinking behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 770–780.

Friend, J. G. (1973). Personal and vocational interplay in identity building: A longitudinal study. Oxford, UK: Branden.

Goossens, L. (2001). Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 681–699.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Applying Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise in career guidance and counseling. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 71–100). New York: Wiley.

Graham, C. W., Sorell, G. T., & Montgomery, M. J. (2004). Role-related identity structure in adult women. Identity, 4, 251–254.

Granic, I., Dishion, T. J., & Hollenstein, T. (2003). The family ecology of adolescence: A dynamic systems perspective on normative development. In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 60–91). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Grotevant, H. D., & Thorbecke, W. L. (1982). Sex differences in styles of occupational identity formation in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 18, 396–405.

Gushue, G. V., Scanlan, K. R. L., Pantzer, K. M., & Clarke, C. P. (2006). The relationship of career decision-making self-efficacy, vocational identity, and career exploration behavior in African American high school students. Journal of Career Development, 33, 19–28.

Hall, D. T. (2002). Careers in and out of organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hamilton, S. F. (1990). Apprenticeship for adulthood: Preparing youth for the future. New York: Free Press.

Hansen, D. M., Larson, R. W., & Dworkin, J. B. (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: A survey of self-reported developmental experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 25–55.

Hargrove, B. K., Creagh, M. G., & Burgess, B. L. (2002). Family interaction patterns as predictors of vocational identity and career decision-making self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 185–201.

Hargrove, B. K., Inman, A. G., & Crane, R. L. (2005). Family interaction patterns, career planning attitudes, and vocational identity of high school adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 31, 263–278.

Harris, R., Simons, M., Willis, P., & Carden, P. (2003). Exploring complementarity in on- and off-job training for apprenticeships. International Journal of Training and Development, 7, 82–92.

Hartung, P. J., Lewis, D. M., May, K., & Niles, S. G. (2002). Family interaction patterns and college student career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 10, 78–90.

Hartung, P. J., Porfeli, E. J., & Vondracek, F. W. (2005). Child vocational development: A review and reconsideration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 385–419.

Heinz, W. R., Kelle, U., Witzel, A., & Zinn, J. (1998). Vocational training and career development in Germany: Results from a longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22, 77–101.

Hirschi, A., & Läge, D. (2007). Holland’s secondary constructs of vocational interests and career choice readiness of secondary students. Journal of Individual Differences, 28, 205–218.

Holland, J. L. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Holland, J. L., Daiger, D. C., & Power, P. G. (1980). My vocational situation: Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Holland, J. L., Gottfredson, D. C., & Power, P. G. (1980). Some diagnostic scales for research in decision making and personality: Identity, information, and barriers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1191–1200.

Holland, J. L., & Holland, J. E. (1977). Vocational indecision: More evidence and speculation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 24, 404–414.

Holland, J. L., Johnston, J. A., & Asama, N. F. (1993). The vocational identity scale: A diagnostic and treatment tool. Journal of Career Assessment, 1, 1–12.

Hollinger, C. L. (1988). Toward an understanding of career development among G/T female adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 12, 62–79.

Johnson, J. A. (1987). Influence of adolescent social crowds on the development of vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31, 182–199.

Johnson, P., Buboltz, W. C., & Nichols, C. N. (1999). Parental divorce, family functioning, and vocational identity of college students. Journal of Career Development, 26, 137–146.

Josselson, R. (1987). Finding herself: Pathways to identity development in women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kalil, A., Levine, J. A., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2005). Following in their parents’ footsteps: How characteristics of parental work predict adolescents’ interest in parents’ jobs. In B. Schneider & L. J. Waite (Eds.), Being together, working apart: Dual-career families and the work-life balance (pp. 422–442). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.