Abstract

Over the past decade there has been a notable increase in the use of Task-Technology Fit (TTF) theory within the field of information systems. This theory argues that information system use and performance benefits are attained when an information system is well-suited to the tasks that must be performed. As such, it seeks to offer an account of two of the key outcomes of interest to information systems (IS) researchers. Continued interest in the application of TTF theory is therefore expected and, as a result, the following chapter aims to provide a brief overview of the theory and how it has been applied in prior work. Readers are presented with an overview of the diverse range of research contexts and methodologies that have been used to test and extend TTF theory. Key outcomes of interest to TTF researchers are also examined as are the various approaches that researchers have used to operationalize the notion of TTF. It is hoped that this overview will serve as a sound basis for future research and simultaneously help to ensure that IS research does not continue to tread the same ground.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

Recognition that information systems need to be well-suited to their intended tasks extends back at least as far as the origins of the information systems (IS) discipline (Kanellis et al. 1999). Media richness theory has, for example, been founded on the premise that the decision to use a particular communication technology will be made based on the nature of the specific message to be conveyed (Daft et al. 1987). Similarly, the need for the capabilities of information systems to be suited to their tasks has been highlighted by early research examining information systems adoption (e.g., Thompson et al. 1991). Explicit, formal specification of task-technology fit (TTF) theory did not, however, occur until the publication of three seminal articles during the mid-1990s (Goodhue 1995; Goodhue and Thompson 1995; Zigurs and Buckland 1998). Since the time of these publications, the theory of TTF has been applied extensively to understanding the use of information systems and the consequences of this use in a broad range of personal and professional contexts.

Recent years have been characterized by a notable increase in the use of TTF as evidenced by the number of publications incorporating the theory that have appeared in peer-reviewed journals. This trend suggests growing interest in the theory and how it can be applied to understanding the problems of interest to IS researchers. As a result, the following discussion presents a brief overview of task-technology fit theory and summarizes how it has been applied in prior work. In providing a comprehensive synopsis of the current state of TTF research, this chapter offers important guidance to researchers interested in pursing research that draws on the theory. It is hoped that the resulting understanding will serve as a sound basis for new and innovative applications and extensions of TTF theory within the field of information systems as well as within other disciplines having interest in related problems.

The ensuing discussion commences with a more in-depth description of TTF theory and a synopsis of the various definitions that have been put forth to characterize the notion of TTF. Subsequent to this, a review of prior TTF research is presented that gives some insight into the breadth and depth of this research including the multiplicity of contexts in which the theory has been applied, how the notion of TTF has been measured empirically, and the key outcomes of interest to researchers that have drawn on TTF theory. The chapter closes by offering a summary framework and a brief discussion of some notable issues related to TTF research.

5.2 The Theory

The foundational premise of TTF, that outcomes depend upon the degree of fit or alignment between an information system and the tasks that must be performed, has its roots in organizational contingency theory (Galbraith 1973). In broad terms, contingency theory argues that organizational effectiveness depends upon the extent to which some feature or characteristic of an organization is in accord with the specific circumstances that the organization faces (Doty et al. 1993). Thus, organizational performance outcomes are thought to be dependent upon the level of fit that exists, for example, between the structure of an organization and the environmental and other demands that are present. Numerous analogs to this basic premise have been introduced to the field of information systems as part of efforts to improve our understanding of phenomena such as knowledge management system satisfaction and IT outsourcing success (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal 2001; Lee et al. 2004). One of the most salient of these analogs is, however, the theory of TTF. This theory has been widely used by IS researchers as well as by researchers working within a number of other disciplines.

In addition to its links with contingency theory, the development of TTF theory has drawn extensively upon prior work highlighting the importance of a suitable fit between the representation of a problem and the tasks that must be performed to solve the problem (Vessey 1991). This work suggests that representing a problem in a manner that is ill-suited to the solution process tends to increase cognitive demand and thereby undermines problem-solving performance. Building on this understanding of how performance outcomes can be negatively impacted by inadequate fit, a general model of TTF theory was formulated that asserts the need for a fit or alignment between task characteristics and the capabilities of an information system (Fig. 5.1). Despite subsequent efforts to introduce variations, refinements, and extensions to this general model, TTF theory continues to convey a relatively clear and consistent message. This message is, in essence, that technology use and performance benefits will result when the characteristics of a technology are well-suited to the tasks that must be performed (Goodhue and Thompson 1995; Zigurs and Buckland 1998). The impact of TTF on performance is posited as occurring either directly or indirectly through its impact on technology use.

Notably, the performance benefits posited by TTF can be attained at the level of individual users as well as higher-order levels such as those of the group, team, and organization. Further to this, the general premise of TTF should be regarded as being of relevance to multiple levels of analysis. It has, for example, been argued that the extent to which a technology is well-suited to a group-level task will impact group use of the technology and group-level performance. Similar arguments also exist to suggest that the extent to which a technology is well-suited to an individual level task will impact individual use of the technology and individual performance. Despite this seemingly multilevel character, the overwhelming majority of TTF research has been conducted at the individual level of analysis. Thus, there would appear to be numerous opportunities to conduct more extensive empirical research at other levels of analysis.

In exploring the use of TTF at various levels of analysis it is important for researchers to remain cognizant of the levels of analysis associated with each of the individual constructs incorporated into the theory. By incorporating task, system, individual, and group/organizational level constructs, TTF offers a theoretical mechanism for linking system and task-level phenomena to individual- and group-level outcomes. It is, however, incumbent on researchers to ensure that any transitions in levels of analysis that they posit are suitably justified and operationalized in order to ensure that their work offers substantive and meaningful results. The simplest and most prevalent approach to addressing this issue has typically been to hold the level of analysis constant by, for example, linking individual-level tasks to individual-level technology use and individual-level outcomes. Nonetheless, potentially interesting and important alternative specifications are possible that may offer valuable insights concerning such questions as how individual-level TTF yields organizational benefits.

5.3 Literature Survey and Synopsis

A literature review was conducted to elicit a comprehensive understanding of the breadth and depth of research that has sought to either develop or apply TTF theory. Two prominent literature search services (ABI Inform and EBSCO) were used to search for all peer-reviewed journal articles that specified the words task, technology, and fit either as keywords or in their abstracts. An in-depth review of the resulting set of articles was then undertaken to eliminate spurious results. Emphasis during this review was placed upon identifying only research that explicitly used or developed TTF theory rather than research that relied on general arguments suggesting a need for some form of fit or alignment. Articles that referred to TTF theory only casually or used the theory as relatively incidental support for arguments being made were also excluded from further consideration. During the review process the reference list of every article was examined to identify additional relevant articles. The reference lists of newly identified articles were similarly examined until no new articles could be found. This process ultimately resulted in the identification of a total of 81 articles that had incorporated TTF theory in a substantive manner.

Results of the literature review described in the preceding paragraph suggest considerable proliferation in the publication of research that has drawn on or extends TTF theory in recent years. Over 20 articles were, for example, noted to have been published in the 2-year period beginning in 2008 (Fig. 5.2). In general, the work published in relation to TTF can be divided into three broad categories (Table 5.1). The first of these is individual-level survey research that has sought to apply the theory to improving our understanding of information systems adoption. Given the emphasis of this first category, it is not entirely surprising that it includes some attempts to link and integrate TTF theory to related theories of IS adoption such as the technology acceptance model (TAM) (e.g., Dishaw and Strong 1999). The second category of TTF research is the stream of work that manipulates TTF experimentally to explore the impact of fit on a range of task related outcomes. As such, this body of work is primarily interested in the performance consequences of TTF rather than whether fit contributes to system use. The final significant category of TTF research is a collection of conceptual and review-oriented articles. These articles have primarily sought to advance new theory (e.g., Zigurs and Buckland 1998) or report on some form of meta-analysis conducted in relation to TTF (Dennis et al. 2001). Interestingly, this set of articles also includes a recently published literature review, though this review seems to give only limited consideration to TTF research published subsequent to 2004 (Cane and McCarthy 2009).

5.3.1 Definition of Task-Technology Fit

Discounting minor differences that reflect some of the specific contexts to which TTF theory has been applied, most definitions of TTF tend to suggest that it represents the degree of matching or alignment between the capabilities of an information system and the demands of the tasks that must be performed (Table 5.2). As such, researchers seeking to apply TTF would appear to have a sound basis for operationalizing its central construct. The apparent consistency in these definitions tends, however, to belie the considerable ambiguity and complexity that actually surrounds the notion of TTF. These challenges extend to all three of the key dimensions of the preceding definition. First, it is not especially easy to elucidate the key demands of any given task or, moreover, an entire set of tasks. Second, it can be difficult to clearly establish the most important and relevant capabilities of an information system. Finally, determining whether these capabilities actually match or align with salient task characteristics can present significant challenges. As a consequence, suitable operationalization of TTF can serve as a notable impediment to wider application of the theory. The following discussion thus examines the most prevalent approaches used to operationalize this notion in prior research.

5.3.2 Operationalization of Task-Technology Fit

Prior work has identified a number of alternative approaches that might be used to empirically operationalize the notion of TTF. Although these approaches generally fall into one of six distinct categories (Venkatraman 1989), TTF research has typically adopted one of only two approaches (Junglas et al. 2008). The first approach sees fit as being represented by a match between tasks and the capabilities of an information system. As such, this approach measures fit directly rather than constructing fit measures from other variables and it is this approach that has dominated survey-based TTF research. The second approach argues that fit can be assessed by evaluating the extent to which a technology deviates from a theoretically grounded profile of ideal characteristics. This approach has been used primarily in the context of group support systems research where ideal capabilities can be derived based on such things as the communication needs associated with the task to be performed (e.g., Zigurs and Buckland 1998).

Some of the complexities associated with operationalizing TTF can be avoided by adopting a fit-as-match perspective. In its most basic form, such an operationalization can simply ask users to indicate whether an information system is well-suited to the tasks they must perform (e.g., Lin and Huang 2008). Alternatively, it is possible to identify specific information system capabilities such as reliability and compatibility and then measure the extent to which users perceive task fit on each of these dimensions (e.g., Goodhue 1995; Goodhue and Thompson 1995). Utilizing this latter approach, Goodhue and Thompson (1995) developed a measure of TTF consisting of eight information system capability dimensions. Task fit with these capability dimensions was then measured using a seven-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Similarly, Goodhue (1995, 1998) developed and validated a measure of IS user satisfaction consisting of 12 dimensions that roughly correspond to the eight dimensions identified by Goodhue and Thompson (Table 5.3). Although these measures have undergone numerous modifications to suit the purpose of particular studies, they do provide relatively comprehensive instruments for measuring user perceptions of TTF.

Given the ability of the fit-as-match approach to simplify operationalization of the TTF construct, it is perhaps not surprising that TTF measures relying on it have been widely used. Such measures are, however, not without important limitations. Notably, they tend to be best suited to survey based research, they depend on individuals being able to effectively evaluate fit, and they cannot typically be used to evaluate TTF prior to actual system use. Thus, despite widespread use of the fit-as-match approach in individual-level survey research, only limited application of this approach can be observed in group-level studies or in studies that employ alternative methodologies. In particular, experimental studies have tended to rely on the fit-as-profile approach to operationalizing TTF. This approach requires that a set of technology characteristics considered to provide preferred or ideal support for a particular task be identified and theoretically justified. The extent to which these characteristics are present in a technology is then considered to represent the level of fit that the technology has for the specified task. Operationalizing TTF then involves experimentally manipulating the extent to which a technology provides the ideal set of characteristics (e.g., Murthy and Kerr 2004).

Although fit-as-match and fit-as-profile are the most common approaches to operationalizing TTF, a limited set of studies have attempted to employ alternative approaches. Among the more salient of these are the small group of studies that have incorporated interactions between measures of task characteristics and measures of technology characteristics as measures of TTF (e.g., Strong et al. 2006). Thus, for example, a TTF variable might be constructed as the product of a measure of a task characteristic and the measure of a corresponding information system capability. Notable challenges are, however, presented in relation to the need to determine which task and technology measures should be interacted to produce appropriate fit variables. Care is, for example, warranted in constructing interaction terms between measures of system reliability and characteristics of a task that do not require reliability. Thus, identifying suitable interactions and theoretically justifying each one can be quite complex. As a result, the generalizability of this form of fit measure can be limited, thereby imposing some constraint on the extent to which such interactions have been applied. Nonetheless, limited reliance on the use of other approaches to operationalizing TTF suggests that there is at least some potential for future research that aims to explore the relative merits of these alternatives.

5.3.3 Research Contexts Employed by TTF Research

Although researchers generally attempt to control for contextual factors, it is particularly important that TTF researchers pay attention to their research context given that their theoretical foundation emphasizes the need for a fit between the capabilities of an information system and the specific tasks that must be performed. Context can be expected to have significant implications for both the nature of the tasks that must be performed and the information system capabilities that are available.

To date, TTF theory has been applied in a broad range of research contexts (Table 5.4). Despite the apparent diversity of research contexts observed in this research, it is important to note that the overwhelming majority of experimental research has been conducted with student subjects. Given the many and varied differences between the tasks faced in such contexts and those faced in organizational contexts, there would seem to be considerable opportunity for researchers interested in conducting field experiments. The relatively circumscribed nature of the tasks performed for the majority of the experimental research that has been conducted also suggests opportunities for researchers interested in exploring the nature of TTF across a broader spectrum of tasks.

In contrast with the experimental studies that have been performed, survey based TTF research has been conducted in a wide range of organizational contexts. This work has, however, tended to be based on different research model specifications and inconsistent construct measures. Consequently, there is some room for more work that aims to explore the nature of task-technology fit across contexts using a consistent measure of TTF and a single research model. Such efforts hold the promise of providing a relatively generalizable understanding of TTF that might be more readily applied to other contexts. Initiatives of this sort can also provide valuable insights concerning how a wide range of contextual factors might impact the nature of TTF.

In comparison to more quantitatively oriented survey and experimental studies, relatively little attention has been given to examining TTF using qualitative techniques such as interviews and case studies. However, the work that has been conducted has generally relied on interviews with individual users to elicit some understanding for the nature and importance of TTF in the context being examined. Despite the seemingly limited use of qualitatively oriented research methods, these techniques have been applied in a diverse array of contexts that range from the use of an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system in a mid-sized organization to the use of a voice recognition system by people with disabilities.

5.3.4 Key Outcomes of Interest to TTF Researchers

Two of the more salient outcomes of interest to IS researchers are the extent to which information systems are used and the performance benefits that such use provides (DeLone and McLean 1992). In accordance with this understanding, TTF theory offers an account of both outcomes at multiple levels of analysis. As such, it is well-positioned to provide a comprehensive understanding of the value of information systems and how this value is derived. There has, however, been a notable bifurcation in the particular emphasis placed on each of these two outcomes. Almost since the origins of the theory, a clear distinction can be observed between survey research conducted at the individual level of analysis and experimental work conducted at the individual and group or team level. Survey research has typically focused on individual decisions to adopt and use information systems, thus emphasizing system use as the key dependent variable. In contrast, experimental research has emphasized performance benefits by seeking, predominately, to improve our understanding of how technology characteristics that provide support for tasks such as brainstorming, decision making, and problem solving can improve a range of performance outcomes.

Given the nature of prior work, there are many opportunities for research that aims to better integrate the two key outcome variables when exploring TTF. Such efforts can draw on the growing body of literature that defines and elaborates upon the nature of information systems use (e.g., Barki et al. 2007; Burton-Jones and Gallivan 2007) as well as work that seeks to provide some understanding of individual, group, and organizational performance (e.g., Stock 2004). As a further basis for such effort, Table 5.5 offers a summary of the specific outcomes that have been examined in prior TTF research. Although this table highlights the salience of system use as a key outcome in survey research, it also draws attention to the wide range of performance outcomes that have been explored through experimental research and the extent to which prior survey research has attempted to link TTF theory to the TAM constructs of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

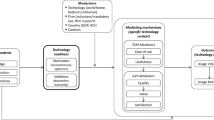

5.3.5 Summary Framework

A summary framework of TTF research was constructed (Fig. 5.3) based on the preceding review in an effort to highlight the key constructs and relationships that have been explored in the TTF literature (Table 5.1). It is important to note that Fig. 5.3 is offered as a graphical overview of the forms of relationships that have been examined in prior research rather than as a research model with associated hypotheses. Nonetheless, examination of Fig. 5.3 suggests that a great deal of the TTF research that has been conducted has tended to remain closely linked to the essence of TTF theory. The five key constructs found in the General Model of Task-Technology Fit (Fig. 5.1) and the interrelationships between them continue to be reflected in Fig. 5.3 as is illustrated by the shaded boxes and bold line relationships in this figure.

Figure 5.3 serves to highlight the challenges surrounding levels of analysis that must be resolved to effectively advance TTF research. For example, there would seem to be some value in improving our explanations of how individual level TTF leads to organizational performance benefits. The literature has, thus far, tended to rely on user perceptions of performance such as perceptions of whether a technology improves productivity. Similarly, Fig. 5.3 draws attention to the general lack of consideration for the impact that organizational and environmental factors might have on TTF. As noted previously, the fundamentally contingent nature of TTF theory calls for greater attention to such factors. Efforts to identify relevant organizational and environmental factors might also help to more clearly establish TTF as a multilevel theory that is equally applicable at the individual, group, and organizational levels of analysis.

5.4 Discussion

The preceding review offers a brief summary of TTF theory and an overview of prior work conducted in relation to this theory. Results of the review suggest that a significant divide exists between work that examines individual-level IS adoption via survey instruments and work that examines team- or group-level performance via laboratory experiments. Thus, it is useful to ask whether experimental findings hold in the field and whether survey results can be refined or extended through the use of alternative methodologies. It is likely, however, that efforts to address such questions will require more extensive examination and specification of what it means for task characteristics to fit with technology characteristics. Greater clarity on this issue can also be expected to facilitate field experiments and support the development of TTF measures that can be employed before a system has actually been used.

Although there is some evidence to suggest that users can effectively evaluate TTF (Goodhue et al. 2000), their ability to do so in advance of system use seems quite limited. Hence, there would seem to be considerable opportunity to explore how TTF can be more fully operationalized in the absence of user evaluations of this notion. Such approaches to evaluating TTF are likely to be of more value to those who must develop and implement new information systems than measures that rely on post hoc user assessments. Further to this, interested researchers may wish to compare the utility of alternative approaches to measuring TTF including perceptual measures, measures based on interaction terms, and fit as defined by theory.

A review of prior TTF research indicates that further effort to better understand the relationships that may exist between individual-, group-, and organizational-level TTF could be of significant value given the potential that TTF has in relation to multilevel and cross-level theory development (Rousseau 1985). Owing to the nature of the core constructs associated with the theory, it offers a potentially important, theoretically grounded mechanism by which task- and technology-level constructs might converge and cross levels to yield individual-, group-, and team-level outcomes. However, relatively limited attention has thus far been directed toward fully exploring this aspect of the theory with, for example, the notion of organizational-level TTF having been essentially unexplored.

As a final note, it is perhaps useful to highlight for prospective researchers that in some cases the tasks to be performed may be endogenous to the technology that is used (Vessey and Galletta 1991). For example, the nature of a particular task can be fundamentally altered by the presence of technology and it can therefore be somewhat difficult to assess fit except, perhaps, in a post hoc sense. Similarly, the capabilities of a technology can be adapted through use and, further to this, research suggests that the capabilities offered by a technology impact how individuals and groups choose to accomplish a given task (Fuller and Dennis 2009). Thus, once again, task and technology become somewhat inseparable. Nonetheless, there is some merit in research that attempts to assess the extent to which such effects occur in practice and the implications that they have for TTF theory and for the implementation and use of information systems in general.

5.5 Conclusion

The preceding discussion has sought to provide a succinct summary of TTF theory, identify the key constructs and relationships posited by the theory, and summarize prior work with a view toward fostering future research initiatives. Although this prior work provides a sound basis for future inquiry, a number of opportunities exist to better link the experimental and survey-based streams of research, to more fully explore the use of TTF theory at multiple levels of analysis, and to examine the character and operationalization of TTF in more depth. Readers are thus encouraged to undertake these and other initiatives in an effort to build upon an important theory that is strongly rooted within the field of information systems.

Abbreviations

- ERP:

-

Enterprise Resource Planning

- IS:

-

Information System

- TAM:

-

Technology Acceptance Model

- TTF:

-

Task-Technology Fit

References

Avital, M., & Te’eni, D. (2009). From generative fit to generative capacity: Exploring an emerging dimension of information systems design and task performance. Information Systems Journal, 19(4), 345–367.

Baloh, P. (2007). The role of fit in knowledge management systems: Tentative propositions of the KMS design. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 19(4), 22–41.

Barki, H., Titah, R., & Boffo, C. (2007). Information system use-related activity: An expanded behavioral conceptualization of individual-level information system use. Information Systems Research, 18(2), 173–192.

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2001). Organization knowledge management: A contingency perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 23–55.

Belanger, F., Collins, R. W., & Cheney, P. H. (2001). Technology requirements and work group communication for telecommuters. Information Systems Research, 12(2), 155–176.

Benford, T. L., & Hunton, J. E. (2000). Incorporating information technology considerations into an expanded model of judgment and decision making in accounting. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 1(1), 54–65.

Burton-Jones, A., & Gallivan, M. J. (2007). Toward a deeper understanding of system usage in organizations: A multilevel perspective. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 31(4), 657–679.

Cane, S., & McCarthy, R. (2009). Analyzing the factors that affect information systems use: A task-technology fit meta-analysis. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 50(1), 108–123.

Chang, H. H. (2008). Intelligent agent’s technology characteristics applied to online auctions’ task: A combined model of TTF and TAM. Technovation, 28(9), 564–577.

D’Ambra, J., & Rice, R. E. (2001). Emerging factors in user evaluation of the world wide web. Information Management, 38(6), 373–384.

D’Ambra, J., & Wilson, C. S. (2004a). Explaining perceived performance of the world wide web: Uncertainty and the task-technology fit model. Internet Research, 14(4), 294–310.

D’Ambra, J., & Wilson, C. S. (2004b). Use of the world wide web for international travel: Integrating the construct of uncertainty in information seeking and the task-technology fit (TTF) model. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 731–742.

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., & Trevino, L. K. (1987). Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: Implications for information systems. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 11(3), 355–366.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60–95.

Dennis, A. R., Wixom, B. H., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2001). Understanding fit and appropriation effects in group support systems via meta-analysis. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 25(2), 167–193.

Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (1998a). Assessing software maintenance tool utilization using task-technology fit and fitness-for-use models. Journal of Software Maintenance: Research and Practice, 10(3), 151–179.

Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (1998b). Supporting software maintenance with software engineering tools: A computed task-technology fit analysis. The Journal of Systems and Software, 44(2), 107–120.

Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (1999). Extending the technology acceptance model with task-technology fit constructs. Information Management, 36(1), 9–21.

Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (2003). The effect of task and tool experience on maintenance CASE tool usage. Information Resources Management Journal, 16(3), 1–16.

Doty, D. H., Glick, W. H., & Huber, G. P. (1993). Fit, equifinality, and organizational effectiveness: A test of two configurational theories. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1196–1250.

Fuller, R. M., & Dennis, A. R. (2009). Does fit matter? The impact of task-technology fit and appropriation on team performance in repeated tasks. Information Systems Research, 20(1), 2–17.

Galbraith, J. R. (1973). Designing complex organizations. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gebauer, J., & Ginsburg, M. (2009). Exploring the black box of task-technology fit. Communications of the ACM, 52(1), 130–135.

Gebauer, J., & Shaw, M. J. (2004). Success factors and impacts of mobile business applications: Results from a mobile e-procurement study. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8(3), 19–41.

Goette, T. (2000). Keys to the adoption and use of voice recognition technology in organizations. Information Technology & People, 13(1), 67–80.

Goodhue, D. L. (1995). Understanding user evaluations of information systems. Management Science, 41(12), 1827–1844.

Goodhue, D. L. (1997). The model underlying the measurement of the impacts of the IIC on the end-users. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(5), 449–453.

Goodhue, D. L. (1998). Development and measurement validity of a task-technology fit instrument for user evaluations of information systems. Decision Sciences, 29(1), 105–138.

Goodhue, D. L., Klein, B. D., & March, S. T. (2000). User evaluations of IS as surrogates for objective performance. Information Management, 38(2), 87–101.

Goodhue, D. L., & Thompson, R. L. (1995). Task-technology fit and individual performance. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 19(2), 213–236.

Goodhue, D. L., Littlefield, R., & Straub, D. W. (1997). The measurement of the impacts of the IIC on the end-users: The survey. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(5), 454–465.

Grossman, M., Aronson, J. E., & McCarthy, R. V. (2005). Does UML make the grade? Insights from the software development community. Information and Software Technology, 47(6), 383–397.

Hahn, J., & Wang, T. (2009). Knowledge management systems and organizational knowledge processing challenges: A field experiment. Decision Support Systems, 47(4), 332–342.

Heine, M. L., Grover, V., & Malhotra, M. K. (2003). The relationship between technology and performance: A meta-analysis of technology models. Omega, 31(3), 189–204.

Ioimo, R. E., & Aronson, J. E. (2003). The benefits of police field mobile computing realized by non-patrol sections of a police department. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 5(3), 195–206.

Jarupathirun, S., & Zahedi, F. M. (2007). Exploring the influence of perceptual factors in the success of web-based spatial DSS. Decision Support Systems, 43(3), 933–951.

Junglas, I., Abraham, C., & Watson, R. T. (2008). Task-technology fit for mobile locatable information systems. Decision Support Systems, 45(4), 1046–1057.

Kacmar, C. J., McManus, D. J., Duggan, E. W., Hale, J. E., & Hale, D. P. (2009). Software development methodologies in organizations: Field investigation of use, acceptance, and application. Information Resources Management Journal, 22(3), 16–39.

Kanellis, P., Lycett, M., & Paul, R. J. (1999). Evaluating business information systems fit: From concept to practical application. European Journal of Information Systems, 8(1), 65–76.

Karimi, J., Somers, T. M., & Gupta, Y. P. (2004). Impact of environmental uncertainty and task characteristics on user satisfaction with data. Information Systems Research, 15(2), 175–193.

Karsh, B.-T., Holden, R., Escoto, K., Alper, S., Scanlon, M., Arnold, J., et al. (2009). Do beliefs about hospital technologies predict nurses’ perceptions of quality of care? A study of task-technology fit in two pediatric hospitals. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 25(5), 374–389.

Klaus, T., Gyires, T., & Wen, H. J. (2003). The use of web-based information systems for non-work activities: An empirical study. Human Systems Management, 22(3), 105–114.

Klopping, I. M., & McKinney, E. (2004). Extending the technology acceptance model and the task-technology fit model to consumer E-commerce. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, 22(1), 35–48.

Kositanurit, B., Ngwenyama, O., & Osei-Bryson, K. M. (2006). An exploration of factors that impact individual performance in an ERP environment: An analysis using multiple analytical techniques. European Journal of Information Systems, 15(6), 556–568.

Lam, T., Cho, V., & Qu, H. (2007). A study of hotel employee behavioral intentions towards adoption of information technology. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 49–65.

Lee, J.-N., Miranda, S. M., & Kim, Y.-M. (2004). IT outsourcing strategies: Universalistic, contingency, and configurational explanations of success. Information Systems Research, 15(2), 110–131.

Lee, C.-C., Cheng, H. K., & Cheng, H.-H. (2007). An empirical study of mobile commerce in insurance industry: Task-technology fit and individual differences. Decision Support Systems, 43(1), 95–110.

Lending, D., & Straub, D. W. (1997). Impacts of an integrated information center on faculty end-users: A qualitative assessment. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(5), 466–471.

Lin, T.-C., & Huang, C.-C. (2008). Understanding knowledge management system usage antecedents: An integration of social cognitive theory and task technology fit. Information Management, 45(6), 410–417.

Lin, T.-C., & Huang, C.-C. (2009). Understanding the determinants of EKR usage from social, technological and personal perspectives. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 165–179.

Lippert, S. K., & Forman, H. (2006). A supply chain study of technology trust and antecedents to technology internalization consequences. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 36(4), 270–288.

Lucas, H. C., Jr., & Spitler, V. (2000). Implementation in a world of workstations and networks. Information Management, 38(2), 119–128.

Maruping, L. M., & Agarwal, R. (2004). Managing team interpersonal processes through technology: A task-technology fit perspective. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 975–990.

Massey, A. P., Montoya-Weiss, M., Hung, C., & Ramesh, V. (2001). Cultural perceptions of task-technology fit. Communications of the ACM, 44(12), 83–84.

Mathieson, K., & Keil, M. (1998). Beyond the interface: Ease of use and task/technology fit. Information Management, 34(4), 221–230.

Murthy, U. S., & Kerr, D. S. (2004). Comparing audit team effectiveness via alternative modes of computer-mediated communication. Auditing, 23(1), 141–152.

Nakatsu, R. T., & Benbasat, I. (2003). Improving the explanatory power of knowledge-based systems: An investigation of content and interface-based enhancements. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man & Cybernetics: Part A, 33(3), 344–357.

Nance, W. D., & Straub, D. W. (1996). An investigation of task/technology fit and information technology choices in knowledge work. Journal of Information Technology Management, 7(3 & 4), 1–14.

Norzaidi, M. D., Siong Choy, C., Murali, R., & Salwani, M. I. (2007). Intranet usage and managers’ performance in the port industry. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(8), 1227–1250.

Norzaidi, M. D., Chong, S. C., Murali, R., & Salwani, M. I. (2009). Towards a holistic model in investigating the effects of intranet usage on managerial performance: A study on Malaysian port industry. Maritime Policy & Management, 36(3), 269–289.

Pendharkar, P. C., Khosrowpour, M., & Rodger, J. A. (2001). Development and testing of an instrument for measuring the user evaluations of information technology in health care. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 41(4), 84–89.

Potter, R. E., & Balthazard, P. A. (2000). Supporting integrative negotiation via computer mediated communication technologies an empirical example with geographically dispersed Chinese and American negotiators. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 7–32.

Raman, P., Wittmann, C. M., & Rauseo, N. A. (2006). Leveraging CRM for sales: The role of organizational capabilities in successful CRM implementation. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(1), 39–53.

Rousseau, D. M. (1985). Issues of level in organizational research: Multi-level and cross-level perspectives. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 1–37.

Shirani, A. I., Tafti, M. H. A., & Affisco, J. F. (1999). Task and technology fit: A comparison of two technologies for synchronous and asynchronous group communication. Information Management, 36(3), 139–150.

Staples, D. S., & Seddon, P. (2004). Testing the technology-to-performance chain model. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 16(4), 17–36.

Stock, R. (2004). Drivers of team performance: What do we know and what have we still to learn? Schmalenbach Business Review, 56(3), 274–306.

Strong, D. M., Dishaw, M. T., & Bandy, D. B. (2006). Extending task technology fit with computer self-efficacy. Database for Advances in Information Systems, 37(2/3), 96–107.

Teo, T. S. H., & Bing, M. (2008). Knowledge portals in Chinese consulting firms: A task-technology fit perspective. European Journal of Information Systems, 17(6), 557–574.

Thompson, R. L., Higgins, C. A., & Howell, J. M. (1991). Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 15(1), 125–143.

Tjahjono, B. (2009). Supporting shop floor workers with a multimedia task-oriented information system. Computers in Industry, 60(4), 257–265.

Todd, P., & Benbasat, I. (1999). Evaluating the impact of DSS, cognitive effort, and incentives on strategy selection. Information Systems Research, 10(4), 356–374.

Venkatraman, N. (1989). The concept of fit in strategy research: Toward verbal and statistical correspondence. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 423–444.

Vessey, I. (1991). Cognitive fit: A theory-based analysis of the graphs versus tables literature. Decision Sciences, 22(2), 219–240.

Vessey, I., & Galletta, D. (1991). Cognitive fit: An empirical study of information acquisition. Information Systems Research, 2(1), 63–84.

Vlahos, G. E., Ferratt, T. W., & Knoepfle, G. (2004). The use of computer-based information systems by German managers to support decision making. Information Management, 41(6), 763–779.

Wilson, E. V., & Sheetz, S. D. (2008). Context counts: Effects of work versus non-work context on participants’ perceptions of fit in e-mail versus face-to-face communication. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 2008(22), 311–338.

Wongpinunwatana, N., Ferguson, C., & Bowen, P. (2000). An experimental investigation of the effects of artificial intelligence systems on the training of novice auditors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 15(6), 306–318.

Wu, J.-H., Chen, Y.-C., & Lin, L.-M. (2007). Empirical evaluation of the revised end user computing acceptance model. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(1), 162–174.

Wu, J.-H., Shin, S.-S., & Heng, M. S. H. (2007). A methodology for ERP misfit analysis. Information Management, 44(8), 666–680.

Zhou, Z., Guoxin, L. I., & Lam, T. (2009). The role of task-fit in employees’ adoption of it in Chinese hotels. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 8(1), 96–105.

Zigurs, I., & Buckland, B. K. (1998). A theory of task/technology fit and group support systems effectiveness. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 22(3), 313–334.

Zigurs, I., & Khazanchi, D. (2008). From profiles to patterns: A new view of task-technology fit. Information Systems Management, 25(1), 8–13.

Zigurs, I., Buckland, B. K., Connolly, J. R., & Wilson, E. V. (1999). A test of task-technology fit theory for group support systems. Database for Advances in Information Systems, 30(3/4), 34–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Furneaux, B. (2012). Task-Technology Fit Theory: A Survey and Synopsis of the Literature. In: Dwivedi, Y., Wade, M., Schneberger, S. (eds) Information Systems Theory. Integrated Series in Information Systems, vol 28. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6108-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6108-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4419-6107-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4419-6108-2

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)