Entrepreneurship involves the establishment of new organizations and the development of new economic activities. Its consequences have not been experienced before and thus are rife with risk and uncertainty. Those who engage in such activities have consequently been considered as being willing to take on more risk and uncertainty than others. Empirical work, however, has demonstrated that entrepreneurs are not willing to take more risks than non-entrepreneurs (Busenitz and Barney 1997; Miner and Raju 2004; Palich and Bagby 1995; Wu and Knott 2006). Therefore, a corresponding difference in general risk propensity hypothesis is not supported by research findings. Alternatively, a difference in risk perception hypothesis has been suggested. In other words, even if entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs have similar risk preferences, entrepreneurs may perceive less risk by overestimating their chances for success (Baron 1998).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship involves the establishment of new organizations and the development of new economic activities. Its consequences have not been experienced before and thus are rife with risk and uncertainty. Those who engage in such activities have consequently been considered as being willing to take on more risk and uncertainty than others. Empirical work, however, has demonstrated that entrepreneurs are not willing to take more risks than non-entrepreneurs (Busenitz and Barney 1997; Miner and Raju 2004; Palich and Bagby 1995; Wu and Knott 2006). Therefore, a corresponding difference in general risk propensity hypothesis is not supported by research findings. Alternatively, a difference in risk perception hypothesis has been suggested. In other words, even if entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs have similar risk preferences, entrepreneurs may perceive less risk by overestimating their chances for success (Baron 1998). Differences in risk perception, or how an individual perceives patterns of odds and probabilities, have been of particular interest to economists dealing with economic decisions under risk and uncertainty (Bernardo and Welch 2001; Felton et al. 2003; Puri and Robinson 2007; Weber and Milliman 1997; Wu and Knott 2006) as well as management scholars examining entrepreneurial decision making and entrepreneurs’ positively biased perceptions of their venture’s risk (Baron 1998, 2004; Busenitz and Barney 1997; Forlani and Mullins 2000; Keh et al. 2002; Norton and Moore 2006; Simon et al. 2000).

1.1 Risk Perceptions, Self-Efficacy, and Internal Locus of Control

The perception of risk and, thus, expectancies about the outcomes of an entrepreneurial activity depend on various other expectancies, including the probabilistic estimates of outcomes and the controllability of outcome attainment (Sitkin and Pablo 1992; Sitkin and Weingart 1995). In particular, Miller (2007) describes how the outcomes of types of entrepreneurial processes (e.g., opportunity recognition, opportunity discovery, and opportunity creation) are dependent on contingencies that can be unpredictable, unknowable, and uncontrollable. Bandura (1997) suggests a simpler model based on social cognitive theory, in which outcome expectancies depend on two major elements that underlie Miller’s three dimensions: self-efficacy, the belief of whether or not one is able to put required actions into practice, and locus of control, the belief of whether or not one’s outcomes depend mainly on one’s own actions or on factors not under one’s control.

Empirical studies in the area of entrepreneurship provide initial justification for the inclusion of both self-efficacy and locus of control in our model of risk perception. Regarding self-efficacy, Krueger and Dickson (1994) report that business executives who show greater self-efficacy will perceive opportunities and threats differently and will take more risks. Likewise, Simon et al. (2000) demonstrate for students and Keh et al. (2002) demonstrate for entrepreneurs that the evaluation of a business opportunity depends on control beliefs. While self-efficacy (Gatewood et al. 1995; Gatewood et al. 2002; Krueger and Dickson 1994) and locus of control (Keh et al. 2002; Simon et al. 2000) have been investigated separately in entrepreneurship research, their joint effects have not. Further, other sources of efficacy and control have likewise received little or no attention.

1.2 From a Single to a Multidimensional Model

In their Nobel Prize winning paper, Tversky and Kahneman (1992) list five major empirical phenomena that descriptive theories of decision making should deal with: framing effects, nonlinear preferences, source dependence, risk seeking, and loss aversion. It is interesting to note that of the five phenomena only source dependence has not been incorporated into more recent decision-making theories (compare, for example, Steel and König 2006). Source dependency describes the fact that the evaluation of risk and uncertainty might depend on the source, which could be a throw of the dice or a task that one has to solve based on their own competence. In fact, different combinations of sources of risk could explain why different people perceive the total risk differently. For example, entrepreneurship researchers including Busenitz and Barney (1997) and Janney and Dess (2006) have proposed that one reason why entrepreneurs and managers of large firms perceive risk differently is “that entrepreneurs face a different composition of risks than their non-entrepreneurial counterparts” (Janney and Dess 2006: 387).

This empirical need to develop a more comprehensive model of risk perception that takes into account source dependency is demonstrated by research into the additional impact of efficacy beliefs regarding factors external to the individual (Gist and Mitchell 1992; Wu and Knott 2006), as well as efficacy beliefs regarding specific external factors including collective efficacy (DeTienne et al. 2008; Shepherd and Krueger 2002) and belief in good luck (Day and Maltby 2005). For example, in their study of market entry decisions for the US banking industry, Wu and Knott (2006) are one of the first pair of researchers to demonstrate in the same study that both one’s own abilities and one’s expectancies regarding external factors (in their case, market volatility) affect risk taking differently.

Similar to efficacy, external sources of control beliefs should also be addressed in a more comprehensive model of compound-risk perception. The examples for efficacy beliefs mentioned in the paragraph above (i.e., internal versus external and collective versus luck) parallel Levenson’s (1974, 1981) work on social activists, which proposes that external locus of control should distinguish between powerful others and chance. Further, Bandura’s (1997) work on self-efficacy was strongly influenced by earlier work on control beliefs by Rotter (1966). Rotter (1966) discusses the role of beliefs about whether or not the reasons for success and failure are located within a person or outside a person, i.e., an internal or external locus of control. However, based on the analysis of sociopolitical activists (an interesting form of social entrepreneur), Levenson (1974, 1981) and Levenson and Miller (1976) argue that one needs to distinguish external drivers of outcomes with respect to chance and powerful others. This is a critical distinction as powerful others can be influenced by social action but chance cannot. Therefore, coping with dependency on powerful others differs from coping with bad luck.

1.3 The Theory of Mixed Control

In this chapter, we follow Krueger’s (2003) call for more theory-based research on entrepreneurial cognition and contribute by developing a model of compound-risk perception. Based on the aggregated insights of the existing theories related to multiple sources of efficacy and locus of control, we introduce the theory of mixed control, a theory developed by Urbig and Monsen (2009) that incorporates both efficacy beliefs and control beliefs to explain outcome expectancies and thus perceptions of risk. While both constructs have been anticipated in research on entrepreneurship, recent results reported in psychological research on the interaction of both constructs have not received attention by entrepreneurship research. Furthermore, self-efficacy has been frequently investigated in the entrepreneurial context, but beliefs regarding the efficacy of external factors of success are only beginning to receive attention from researchers.

The interaction of efficacy and control beliefs as well as a corresponding integration of beliefs regarding one’s own efficacy and the efficacy of external factors is at the core of the theory of mixed control. This theory considers outcome expectancies as being composed of expectancies regarding three distinct sources of risk (self, others, and chance). Beliefs about the efficacy of these elements are weighted by the degree to which these elements are perceived to control the outcome. This reflects one important empirical observation that deviates from traditional decision theories: Entrepreneurship is a complex activity involving multiple sources of risk. While the second part of this chapter deals with this multidimensionality, the third part briefly discusses a second important empirical observation: Expectancies are not only learned, but can be endogenous and thus depend on future actions of the entrepreneur. The chapter concludes with a discussion of contributions of the theory of mixed control for more robust decision research.

1.4 Distinctions and Definitions

For this chapter three distinctions are vital: unconditional versus conditional expectancies, preference versus perception, and single- versus multidimensional conceptualizations of sources of risk.

Expectancies regarding an event describe beliefs of the likelihood of the occurrence of an event. Unconditional expectancies are related to a single event or a set of independent events (e.g., P[A] and P[O]). Efficacy beliefs, the expectancy that a particular antecedent or source A will be helpful or useful (e.g., e A ≈ P[A]), positive outcome expectancy, the expectancy that a particular positive outcome O will occur (e.g., π ≈ P[O]), and perceived risk, the expectancy that a particular positive outcome will not occur (i.e., ρ = 1 – π) are considered unconditional expectancies. For example, in the entrepreneurship literature, risk has been defined as the probability or likelihood of a downside loss or upside gain from the pursuit of an opportunity (compare Janney and Dess 2006). In contrast, when defining locus of control, Rotter (1966) refers to the conditional expectancy that an event (e.g., outcome O) happens given that another event (e.g., behavioral antecedent A) occurs. An event is considered to “control” another event if the occurrence of the first event affects the likelihood of the second event. We, therefore, refer to the expectancy that both events are linked by a causal relation (e.g., c A ≈ P[O|A]) as control beliefs. This is reflected later in this chapter in our theory of mixed control and model of compound-risk perception, in which “unconditional” perceived risk ρ is one minus positive outcome expectancy π, which is the sum of the products of multiple source-dependent “unconditional” efficacy beliefs and “conditional” control beliefs:

The second distinction to be made is between preference and perception. Whereas perceived risk reflects the expectancy or probability of an outcome, risk preference reflects the shape of the utility function for a series of related risky choices (Weber and Milliman 1997). Kahneman and Tversky (1979) emphasize this point by distinguishing overweighing reflecting a preference from overestimating reflecting a biased perception. Perceptions of risk and the sources of risk may not only affect the evaluation of businesses opportunities. Entrepreneurs may also have specific preferences regarding both the level of risk they are willing to assume and the sources of that risk (Janney and Dess 2006; Miller 2007; Monsen et al. in press), which can moderate the impact of risk perceptions on decision making (Pablo et al. 1996). These can lead to counterintuitive results, which the core perception-only model in this chapter does not address. For example, given that many entrepreneurs have a taste for variety (Astebro and Thompson 2007), they may choose to take a risk in an area which they are low on efficacy, but do so with the confidence that they will quickly learn what they need to know. Furthermore, given that many entrepreneurs have a need for autonomy and control (Cromie 1987; Kuratko et al. 1997; Monsen et al. 2007), entrepreneurs may give more weight to control than non-entrepreneurs in evaluating opportunities. Before we address the role of risk preferences on decision making, however, we need to better understand and have a better core model of how those risks are perceived, independent of preferences. Therefore, in this chapter, we focus on risk perception and only consider the effects of control and efficacy beliefs on outcome expectancies.

The third distinction is between single- and multidimensional conceptualizations of sources of risk. Traditional research on self-efficacy and internal locus of control can be considered single-dimensional, in that it focuses on the individual self. However, entrepreneurial productivity (Parker 2006) and persistence (DeTienne et al. 2008) are affected by both entrepreneurial ability and market forces, thus, more dimensions should be considered. For example, Gist and Mitchell (1992) propose that self-efficacy is determined by both internal and external factors. Of particular interest for this chapter, Gist and Mitchell propose that external factors can be attributed to factors “under the control of others” (1992: 196) and “luck-oriented factors” (1992: 197). Regarding dependence on others, recent research on entrepreneurship has identified collective efficacy as an important construct for explaining entrepreneurial intentions (Shepherd and Krueger 2002) and persistence (DeTienne et al. 2008). Furthermore, in a three-dimensional conceptualization of locus of control developed for research into social activists, Levenson (1974, 1981) introduces not only powerful others but also chance as an additional driver of outcomes (see also Bonnett and Furnham 1991; Furnham 1986). Closing the theoretical circle, Bandura (2001) outlines in a recent review article on social cognitive theory multiple sources of agency, including personal, proxy, collective, and fortune. All in all, this suggests that an individual’s perception of risk is driven not only by personal efficacy and control beliefs but also by their beliefs of whether other people or chance rules the world and how these may help or hinder one’s success.

1.5 Roadmap for Chapter

Given the multidisciplinary nature of entrepreneurship research and its connection with disciplines as distinct as psychological and economic research, our discussion will be along three lines. First, we briefly review the current theoretical and empirical literature on efficacy, control, and risk perception and develop in a step-by-step manner our theory of mixed control. Next, to make our theory more precise and testable, we develop in parallel a mathematical formulation of our compound-risk perception function. Finally, to concretely illustrate what our theory means in day-to-day practice, we conclude each section of the theory and mathematical development with a hypothetical story of a day in the life of “Joe the Entrepreneur,” as he wrestles with the question of whether to become an entrepreneur or not.

2 Static Theory of Mixed Control

The theory of mixed control considers risk perception as a process and perceived risk, i.e., outcome expectancies, as the dependent variable. The theory describes how people’s overall perceived risk regarding desired or undesired outcomes is influenced by other more specific expectancies regarding the efficacy and control of three generic sources: self, others, and chance. Grounded in a review of the current theoretical and empirical literature on efficacy, control, and risk perception, we develop our theory of mixed control in a step-by-step manner. Beginning with established research on the independent effects of self-efficacy and internal locus of control on risk perception, we then apply recent ideas and research on the interaction of self-efficacy and control beliefs to extend our model. Next, we go beyond the single dimension of the self and first add a general external source of efficacy, followed by a division between others and chance as independent external sources of efficacy and control. At the close of the section, we discuss how our compound-risk perception function can be used to augment current existing decision-making theories.

In parallel, in order to make our theory more precise and testable, we develop a corresponding mathematical formulation of our compound-risk perception function and theory of mixed control, which parallels the formalization by Urbig and Monsen (2009). Mathematical modeling is not uncommon in the field of entrepreneurship (Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Parker 2006) and provides a useful second language to precisely express the meaning of the text-based theory and to test its consistency and coherence (Lévesque 2004). To begin, we consider the function f(·) that maps a set of independent variables onto positive outcome expectancy π and perceived risk ρ = 1 – π. If, for instance, positive outcome expectancy π depends positively on self-efficacy e s we will write that the function π = f(e s) is characterized by δ f(e s)/δ e s>0. While π represents the perceived expectancy of a specific outcome, the function f could be considered as the perceived production of risks associated with a specific outcome. We will exemplify the general mathematical model with a specific function π = f(e s), e.g., π = e s.

Finally, to more concretely illustrate and explain what our theory and math mean in day-to-day practice, we conclude each section of the theoretical and mathematical development with a hypothetical story of a week in the life of “Joe the Entrepreneur.” As the week progresses from Monday to Friday, and our theory and model become more complex, Joe’s life will become correspondingly more complex and as such closer to the reality of day-to-day real-world entrepreneurship.

2.1 Independent Effects of Self-Efficacy and Control Beliefs

To begin, typical models for including control beliefs and self-efficacy into entrepreneurship decision making (Keh et al. 2002; Simon et al. 2000) and intentions (Wilson et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2005) models consider only self-efficacy, only control (Gatewood et al. 2002; Krueger and Dickson 1994), or an independent combination in the form of the theory of planned behavior (Krueger et al. 2000). For example, in a recent revision of the theory of planned behavior, Ajzen (2002) defines the construct of perceived behavioral control as reflecting beliefs about self-efficacy and beliefs about controllability. This raises the question of whether self-efficacy or locus of control matters more in risk taking. Using three carefully designed economic experiments, Goodie and Young (2007) found that while both control and efficacy affect risk-taking behavior, perceptions of control played the more dominant role in risk-taking decisions. Therefore, we initially consider self-efficacy e s and control beliefs c s as independent drivers of risk perception ρ = 1 – π and outcome expectancy π in our mathematical model as

On Monday, “Joe the Entrepreneur” is not yet an entrepreneur, but has woken up with a new and innovative business idea that he is seriously considering. He believes that he has the necessary skills and self-discipline, but is that enough? Before he decides to quit his job and become an entrepreneur, he decides to wait another day, to sleep on it, and to see how he feels the next morning.

2.2 Interaction of Self-Efficacy and Control Beliefs

Since self-efficacy and control beliefs appear to have very similar effects and are often correlated, some consider self-efficacy and locus of control to be reflective of the same univariate core construct (Judge et al. 2003) or the same multivariate construct (Spreitzer 1995; Thomas and Velthouse 1990). However, researchers in the areas of job stress as well as general decision making have demonstrated that self-efficacy and locus of control are distinct constructs and can have not only additive but also interactive effects. In research on job stress, Schaubroeck and Merritt (1997) not only found an interaction effect between perceptions of control and self-efficacy but also found that this interaction moderates the relationship of job demands and job stress, measured by blood pressure. Given that being an entrepreneur is stressful, ambiguous, and uncertain (Monsen and Boss 2009; Schindehutte et al. 2006), we expect to see a similar interaction effect between beliefs of self-efficacy and control and the evaluation of risky opportunities (for example, Mullins and Forlani 2005; Norton and Moore 2006).

Sharpening this line of thought, we claim that the effect of self-efficacy on outcome expectancies and perceived risk is moderated by control beliefs (Bandura 1997; Krueger 2003). Bandura (1997) argues that the judgment about the likelihood of an outcome is based on two types of expectancies: self-efficacy beliefs describe the belief that one’s effort will produce a required performance, while control beliefs describe the strength of the belief that the performance will cause a specific outcome. In Bandura’s (1997) words, “Controllability affects the extent to which efficacy beliefs shape outcome expectancies” (Bandura 1997: 23).

Bandura’s (1997) idea that control beliefs affect the extent to which self-efficacy influences outcome expectancies can be generalized to the idea that control beliefs moderate the extent to which efficacy beliefs influence judgments of outcome probabilities and corresponding risk perceptions. The idea is that if outcomes cannot be controlled, i.e., external factors control the outcome, then beliefs about the efficacy of external factors drive a person’s risk perception. While management researchers have been talking conceptually about this moderating effect for some time (compare Gist 1987; Gist and Mitchell 1992), none to our knowledge have empirically tested this interaction hypothesis in the context of risk perception and entrepreneurial decision making.

Krueger (2003: 114) similarly emphasizes that the “more internal the attribution of causality (e.g., skill or effort)” and the more “controllable” the situation, the stronger the impact of self-efficacy on initiating and persisting in entrepreneurial activity. In other words, a multiplicative model suggests that if one perceives zero self-efficacy (or zero internal locus of control), the outcome expectancy will be zero and the individual will perceive maximum risk, irrespective of the perceived internal locus of control (or self-efficacy).

Our mathematical model thus needs to be extended as follows. The general formalization now utilizes an additional level of derivatives and it requires that these derivatives with respect to one variable are zero if the other variable is zero. An example of this is a simple multiplicative combination of self-efficacy and control beliefs. This model closely reflects the description provided by Bandura (1997).

On Tuesday, “Joe the Entrepreneur” wakes up and once again considers his innovative new business idea. While others might be as skilled if not more so than he, Joe feels increasingly more confident that his self-discipline will be a deciding factor in his eventual success.

2.3 Adding External Sources of Efficacy and Control

Bandura’s (1997) work on self-efficacy was strongly influenced by earlier work on control beliefs by Rotter (1966). Rotter (1966) discusses the role of beliefs about whether or not the reasons for success and failure are located inside a person or outside a person, i.e., an internal or external locus of control. Rotter (1966) conceptualized locus of control as unidimensional, such that a low internal locus of control is equivalent to a high external locus of control:

There is, however, a missing element: While self-efficacy beliefs matter if one has internal control, beliefs about the efficacy of external factors that would matter if one has an external locus of control are not included. While Gist and Mitchell (1992) were one of the first to propose the need to consider both internal and external sources of efficacy, Judge et al. (1997) are to our knowledge among the first to operationally define these external factors; which they call “external core evaluations”. However, Judge et al. (1998) concluded that controlling for core self-evaluations, which includes self-efficacy and internal locus of control, external core evaluations do not have a unique effect on job attitudes. In contrast, testing the effects of external efficacy beliefs on dispositional optimism, Urbig and Monsen (2009) have found significant effects. These authors also report that external control beliefs moderate the influence of external efficacy beliefs.

The basic idea is that in such situations where external factors control one’s outcomes, beliefs about external factors instead of beliefs about internal factors should determine one’s outcome expectancies and perceived risk. This empirical need to develop a more comprehensive model of risk perception that takes into account external sources is likewise demonstrated by research into the additional impact of efficacy beliefs regarding factors external to the individual (Wu and Knott 2006). For example, in their study of market entry decisions for the US banking industry, Wu and Knott (2006) are one of the first pair of researchers to demonstrate in the same study that both one’s own abilities and one’s expectancies regarding external factors (in their case, market volatility) affect risk taking.

For the mathematical formulation of our theory we thus have to add beliefs about the efficacy and control of external factors. We furthermore include that an increase in control beliefs regarding one factor, i.e., self or external, moderates the influence of the corresponding efficacy belief.

This formula, where the outcome expectancy is a sum of efficacy beliefs which are weighted by the degree of control they have, can be transformed into the following form:

This formula demonstrates that the effect of changes in efficacy beliefs depends on the difference of the beliefs in the control of internal (self) and external factors and clearly separates two elements. The first term, i.e., the average of self-efficacy and external efficacy beliefs, reflects the positive direct effect of efficacy beliefs on outcome expectancies. The second term describes that the effect of efficacy beliefs on outcome expectancies and perceived risk is moderated by the difference in control beliefs.

On Wednesday, “Joe the Entrepreneur” starts to write his business plan and realizes that current regulations will make implementing his business idea much more difficult than he originally expected. Further, he does not believe that the government will make an exception for him. Thus, despite his initial self-confidence in his own skill to carry through with his idea, he is beginning to have second thoughts.

2.4 Distinguishing Between Others and Chance as External Sources of Efficacy and Control

At this stage, where outcome expectancies are positively influenced by efficacy beliefs regarding internal as well as external factors and where these effects are moderated by corresponding control beliefs, we have finished the development of the basic version of the theory of mixed control. There is, however, one extension that is useful and necessary to remain consistent with existing literature, i.e., external factors need to be differentiated with respect to other people and chance. For example, Gist and Mitchell (1992: 193) discuss external factors such as “group interdependence” (others) and “distractions such as noise” (chance). Bandura (2001) similarly talks about multiple sources of agency, including personal, proxy, collective, and fortune. To distinguish between the efficacy (or expected helpfulness) of other people and the efficacy (or expected helpfulness) of good luck, we introduce the more precise terms: other efficacy and chance efficacy plus other control and chance control.

Not only has literature already suggested distinguishing efficacy beliefs with respect to other people and chance, but there is also an older stream of literature suggesting differentiating external control with respect to others and chance. More specifically, based on the analysis of sociopolitical activists (an interesting form of social entrepreneur), Levenson (1974, 1981) and Levenson and Miller (1976) argue that one needs to distinguish external drivers of outcomes with respect to powerful others (social environment) and chance (natural environment). This idea of distinguishing between powerful others and chance is later applied to the economic (Furnham 1986) and entrepreneurship education context (Bonnett and Furnham 1991). At the heart of this critical distinction is the idea that powerful others can be influenced by social action but chance cannot. Therefore, coping with dependency on powerful others differs substantially from coping with bad luck. For example, the accumulation and leveraging of social capital is one strategy to address the former and the application of a real options approach is one strategy to address the latter (Janney and Dess 2006).

Regarding other efficacy and other control, recent research on entrepreneurship has identified collective efficacy as an important construct for explaining entrepreneurial intentions (Shepherd and Krueger 2002) and persistence (DeTienne et al. 2008). Collective efficacy refers to beliefs about whether or not a group of people is able to implement required actions to succeed, and thus incorporates self-efficacy and efficacy beliefs regarding other people. In addition to collective efficacy as a source of agency, Bandura (1997, 2001) additionally talks about proxy control. Proxy control refers to the internalization of external control through social networking. Proxy control is therefore a socially mediated control, where a person convinces another person with influence to exert this influence to the benefit of the person out of direct control. In this chapter, we introduce the concept of other efficacy and control, which separates the self from the collective and respectfully refers to the likelihood that others will help the individual and degree of control others can exert regarding attainment of the desired outcome. For extra clarity, it should be noted that Bandura (1997, 2001) (see also, Fernández-Ballesteros et al. 2002), as well as DeTienne et al. (2008) and Shepherd and Krueger (2002), define collective efficacy as a group’s shared belief in its capabilities to organize and execute required actions to produce a given level of attainment. In contrast, other efficacy considers an individual’s own beliefs and perceptions about the efficacy of others to help the individual (compare Schaubroeck et al. 2000).

Moving forward, external efficacy and control beliefs do not only comprise beliefs about other people but also beliefs about nature, fortune, and chance. If not other people’s help, it might still be fate or luck that makes things happen. While literature on collective efficacy refers to the first, entrepreneurship literature and general psychology research have rarely and inconsistently investigated beliefs in good luck (Day and Maltby 2005; see also the discussion in Urbig and Monsen 2009), despite the important role good luck, fortune, and random chance always play both in entrepreneurship (Minniti and Bygrave 2001) and in life (Bandura 1982, 1998, 2001).

At the first glance the term chance efficacy might sound strange or even like a contradiction in terms. It has, however, been used to describe beliefs of jazz artists in the popular press who practiced an artistic technique called aleatory or aleatoricism:

Aleatory enjoyed its best run in the 1960s, when the influence of John Cage's philosophy, if not his actual music, tickled the imagination of avant-gardists the world over. However, so few composers managed to exploit chance with much success, even in timid ways, that interest in such experiments gradually dried up. Today, Mr. Lutoslawski is one of few remaining believers in the efficacy of chance in music, possibly because as a Pole he feels attracted to the idea of freedom in any guise. (Henahan 1988: 36)

Jazz has been used as a metaphor for improvisation and creativity in the management (Crossan et al. 2005) and in the entrepreneurship literatures (Hmieleski and Corbett 2008). Jazz is a particularly relevant metaphor for our theory of mixed control, as jazz combines individual (self) and group (other) skills and abilities with the chance of the moment:

Therefore, based on a rich repertoire of research on sources of external efficacy and control beliefs, we conclude that it is appropriate to distinguish at least three dimensions of control: self, others, and chance. Our formal model is thus enhanced as follows:

Similar to the transformation from Equation (12.5) into (12.6), where only the internal and external dimensions were considered, we can perform the same transformation for the three-dimensional version.

Comparing the two- with the three-dimensional example of the outcome expectancy function, only the third term is new. We thus have a formal representation where the different models, starting from self-only models, to internal-versus-external models, to three-dimensional models, are nested into each other. One can thus use the three-dimensional model and explicitly test whether or not splitting of the external factors is statistically significant in a particular context or not.

On Thursday, “Joe the Entrepreneur” decides to role the dice and to pursue his new business idea. Despite the fact that government regulations and officials may stand in his way, Joe feels that in this chaotic and fast changing world, luck plays a major role in who makes it big. Fortunately, luck has never let Joe down in the past, and he believes that luck will be on his side in the future.

2.5 An Alternative Full-Multiplicative or Production Function Model

Up to this point, we have simply added together the terms representing the three sources of risk perception (i.e., self, other, chance). One potential limitation of this functional form is that a zero-level expectancy regarding one source does not result in corresponding zero-level expectancy for the overall outcome. In other words, expectations associated with different sources are independent of one another, an assumption that could lead to positively biased predictions of outcome expectancies and correspondingly negatively biased predictions of perceived risk. An alternative, multiplicative variation of our TMC theory assumes that source-specific risks are not independent. This implies that a zero-level expectancy regarding one source results in corresponding zero-level expectancy for the overall outcome, independent of the other sources. A Cobb–Douglas-style function, a form commonly used in the economics literature to represent economic production and growth (Cobb and Douglas 1928), can represent this variation of the model:

On Friday, “Joe the Entrepreneur” once again reconsiders his plan to pursue his new business idea. In spite of his self-confidence and lucky feeling, his serious doubts about the government making an exception for his new idea overwhelmingly darkens his original optimism.

2.6 Augmenting Current Decision-Making Theories

Our model of the joint effects of efficacy and control can be used not only to predict risk perception but also to augment decision-making models and theories which are based on subjective probabilities. These models include but are not limited to expected utility theory (Bernoulli 1738; Schoemaker 1982), prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979), security-potential/aspiration theory (Lopes 1987; Lopes and Oden 1999), and cumulative prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman 1992).

Expected utility theory, as proposed by Bernoulli (1738) and reviewed by Schoemaker (1982), states that people maximize the sum of the utilities (as opposed to absolute monetary gains) associated with outcomes weighed by the probabilities of the occurrence of these outcomes. Later empirical work has revealed that people do not weight utilities with the exact probabilities, but that they attach a decision weight that is a monotonic but nevertheless a nonlinear function of probabilities, e.g., overweighing of small and underweighting of large probabilities (e.g., prospect theory by Kahneman and Tversky 1979). While those early theories assumed that people hold precise beliefs about the probability of occurrence of an event, later theories relaxed this assumption and integrated uncertainty which implies that people do not need to have precise probability judgments, for example, cumulative prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman 1992) and related non-expected utility theories (Machina 1989; Starmer 2000).

While recent empirical work suggests that the decision weights associated with various outcomes of a behavior may depend on whether or not one can influence the outcome (e.g., Heath and Tversky 1991; Kilka and Weber 2001), recent descriptive theories do not incorporate these findings. Building on the suggestion of Kilka and Weber (2001) that control beliefs and self-efficacy might influence the decision weighting in prospect theory, our production of perceived risk function based on the theory of mixed control provides a unified framework to explain how these beliefs interact. We thus provide a rationale for Goodie and Young’s (2007) finding that sometimes self-efficacy and sometimes control beliefs are more relevant. Furthermore, by replacing the single variable for subjective probability (risk or expectancy) in the respective model with our multivariate function for the risk perception, the yet unresolved issue of source dependence raised by Tversky and Kahneman (1992) and discussed earlier in this chapter is resolved. Moreover, the issue of source dependence is resolved within the context of established decision-making theories and without having to design and validate a risky new decision-making theory.

The functional form of the subjectively perceived risk can, for instance, be embedded into cumulative prospect theory (CPT) (Tversky and Kahneman 1992) by replacing the argument of the probability weighing function with the risk production function suggested above. The source dependency is then combined with those characteristics captured by the CPT, e.g., the underweighting of small probabilities of extreme events. We believe that such models are a promising path for future research and will be better able to measure and predict entrepreneurs’ risk-taking behavior in situations that are more complex and driven by multiple sources of risk (Mullins and Forlani 2005; Norton and Moore 2006; Simon et al. 2000; Wu and Knott 2006), instead of the simpler examples of single-risk-source situations, such as flipping coins or strategizing against opponents (Bernardo and Welch 2001; Camerer and Lovallo 1999; Forlani and Mullins 2000).

3 Dynamic Perspectives

In the previous section we developed the theory of mixed control. The theory is static, insofar as it postulates dependencies between expectancies without considering if and how these expectancies may evolve over time. As such, the theory has its limitations. The following section briefly discusses a more dynamic perspective on the various ways of how efficacy and control beliefs may change over time through reactive learning and proactive behaviors and how expectations of future events and decisions can affect current risk perceptions and decision making.

What do processes look like that change perceived odds, efficacy, or control beliefs? In general, these processes can be associated with one of two classes: learning about the world and changing the world. On the one hand, one can learn about how the world works through observation and thereby adjust one’s behavior as a reaction to the environment; on the other hand, one can proactively engage in behaviors to change the world. These two classes parallel Sarasvathy’s (2001) two logics of thought driving business people’s behaviors. Learning about the world reflects the logic of “to the extent we can predict the future, we can control it” (2001: 252), while changing the world reflects the logic of “to the extent that we can control the future, we do not need to predict it" (2001: 252). Through both processes, learning about and changing the world, one updates one’s beliefs about the impact and nature of the various sources of risk. One can, for instance, learn about the nature of a new business opportunity (see, for example, Bernardo and Welch 2001; Choi et al. 2008). One can also learn about other people and especially about potential competitors. As reported by Moore et al. (2007), this is, however, underutilized by business people. On the other hand, one could try to change the world and if one believes that these changes were successful, beliefs about the world will change too. If one actively engages in social networking and supports other people (i.e., creating and maintaining social capital), one might believe that these people are also willing to help once help becomes necessary for oneself (compare Adler and Kwon 2002; Fehr and Schmidt 1999).

Both types of processes that change efficacy and control beliefs, i.e., learning about and changing the world, refer to changes about how one perceives the world. It can nevertheless happen that one falsely believes that the world has changed or learns systematically or accidentally the wrong things about the world. While it is definitely worth investigating when such learning of false beliefs occurs (see, for example, Moore et al. 2007), for the theory of mixed control, only people’s perceptions are relevant, whether or not their perceptions accurately reflect reality (for a more detailed discussion of perception, we refer the reader to Chapter 1 of this book). The distinction between learning about and changing the world will structure the following discussion. In particular, note that practicing and training has two effects: learning about one’s capabilities and improving them. At the end of the discussion, we highlight that as a consequence of entrepreneurs being able to change the world, the perception of risk is moderated by entrepreneurs’ future decision and actions and thus we suggest one mechanism of how future choice and preferences can affect one’s risk perception, which then affects one’s current choices.

3.1 Learning About the World

Beliefs about the world can change due to interactions with the world, observations of the world, or by communicating with others who know different things about the world. Beliefs change by perceiving new information, for instance, about whether other people are helpful or not and whether one’s favored outcomes have high or low likelihood of occurring (Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Parker 2006). For instance, based on an experiment, Krueger and Dickson (1994) report that executives’ positive and negative feedback about past risk taking affects their future risk taking. In contrast to negative feedback, positive feedback encourages people to see more opportunities instead of threats. Similar results were obtained by Gatewood et al. (2002) in a study with students. In the context of our theory, the new information can be related (1) to self, other, and chance efficacy beliefs, i.e., the perceived extent to which these internal and external factors help or hinder one’s success; (2) to self, other, and chance control beliefs, i.e., the perceived degree to which different factors affect one’s outcomes; or (3) to outcome expectancies, i.e., perceived risk.

In the first two cases, changes to efficacy and control beliefs through learning lead to corresponding changes in one’s outcome expectancies and perceived risks as these are a function of the two sets of beliefs. In the third case, however, one only learns that the perceived risk needs to be adjusted, i.e., one was too optimistic or pessimistic, without knowing why. In contrast to mathematical models where the outcome expectancy is not explicitly considered to be composed of multiple sources of risk (Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Parker 2006), our model explicitly considers different sources of risk and types of beliefs and is closer to modeling reality. For example, when someone unexpectedly fails, there can be multiple reasons for that failure, and a person therefore needs to figure out which of the efficacy and control beliefs about the multiple sources of risk need to be adjusted. One might learn that one is not as good as expected, i.e., adjust self-efficacy beliefs downward. There are models of learning for efficacy beliefs, especially self-efficacy (Gist 1987, 1989; Gist and Mitchell 1992) in the management literature but are beyond the scope of this chapter. For more details on the antecedents of self-efficacy, we refer the reader to Chapter 11 in this book.

Just as one can learn about self-efficacy, one can also learn about the efficacy of external factors, such as others (e.g., markets, see Parker 2006) and chance (e.g., luck, see Minniti and Bygrave 2001). For adjustments of efficacy beliefs about internal or external factors, it is, however, necessary that the person believes that these factors have a controlling influence. Generalizing this, we claim that control beliefs affect the impact that experiences have on efficacy beliefs regarding the self and external factors. This is supported by Gist (1987; 1989), who argues that those with an internal locus of control adjust their self-efficacy beliefs faster.

Instead of learning that the efficacy of various factors is smaller than expected, one might also start believing that unfavorable external factors have more control than originally expected, i.e., adjust control beliefs more toward external control (i.e., other and chance). Such changes in control beliefs are at the heart of the theory of learned helplessness (Abramson et al. 1978; Peterson et al. 1993) and learned optimism (Seligman 1991). Seligman (1991) argues that optimists and pessimists differ with respect to their perception of the reasons for past successes and failures and how these beliefs apply to future events. This concept of learned helplessness has been applied by a number of management (Gist and Mitchell 1992; Sitkin and Pablo 1992; Sitkin and Weingart 1995) and entrepreneurship (Krueger et al. 2000; Markman et al. 2005) researchers who discuss reacting to and coping with failure. Seligman (1991) develops an idea of how control beliefs may change over time and what this change might depend on, thus establishing a learning perspective for control beliefs. There are also models of learning for control beliefs (Logan and Ganster 2005, 2007) in the management literature that are also beyond the scope of this chapter.

3.2 Changing the World: Beating the Odds

Changes in world beliefs can also be internally driven, for instance, when people change reality and the environment around them to change and beat the odds (Sarasvathy 2001). Instead of considering entrepreneurs as belief holders who only react to their environment, Sarasvathy (2001) puts forward the idea that entrepreneurs proactively create their environment and even believe that they are able to beat the odds. At the heart of this claim is the idea that entrepreneurship is a situation under partial control. Entrepreneurs change the odds and adjust the world to make success happen. A consequence of this logic is the exploitation of situations under one’s control and the minimization of dependencies on external factors as much as possible. However, this leads to high outcome expectancies only if one perceives a high self-efficacy. Changing the world is thus related to internalization of control and to increasing self-efficacy.

The idea to take over control is consistent with Knight (1921), who argued that individuals, when faced with uncertainty, either try to reduce the uncertainty, e.g., take control of the situation, or choose to do something else. Along these lines, in his work on self-efficacy, Bandura (1997, 2001) proposes that one can internalize external control through social networking which provides proxy control. In contrast to direct control, proxy control is a socially mediated control, where a person convinces another person with influence to exert this influence to the benefit of the person out of direct control. In order to take control of the situation in an entrepreneurial context, Janney and Dess (2006) recommend the application of real options reasoning and leveraging social capital to gather specialized knowledge, to reduce information asymmetries, to convert chance and other control into internal/self control, and in turn to reduce perceptions of risk. Furthermore, learning by means of increasing one’s competence and thus increasing one’s efficacy complements Janney and Dess’ strategies that target the social environment and the uncertainties about the outside world. All three strategies aim at changing the odds associated with the internal and external factors of one’s success.

3.3 Anticipating Future Behavior: Endogeneity of Risk Perceptions

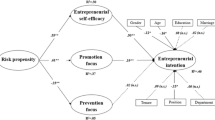

If potential and actual entrepreneurs can allocate their effort to change the odds, then compound-risk perception will also be a function of their allocation processes. Consider, for example, regulatory focus theory (Brockner et al. 2004; Higgins et al. 1997). Building on security-potential/aspiration theory (Lopes 1987; Lopes and Oden 1999), regulatory focus theory states that people choose their options according to the preferences for gains and losses. People with promotion focus try to maximize the gains while those with a prevention focus try to minimize the losses (Higgins et al. 1997). If we assume that entrepreneurship is a complex activity composed of a sequence of decisions, then a person may anticipate future decisions in making present decisions. Since these decisions can influence the risk structure, e.g., buying an insurance policy against losses or investing in a risky but highly innovative project, decision makers may anticipate such future decisions and perceive risk differently (Brockner et al. 2004). In such a situation, risk perception is thus moderated by future decisions and is therefore endogenous. For individuals with promotion focus, we expect that they would change the expectancies such that the expectancies for gains will increase, while those with prevention focus engage in activities that decrease expectancies for losses. Since future behavior is affected by one’s preferences and evaluations of outcomes, these preferences and outcomes, therefore, indirectly affect one’s perception of risk associated with a complex activity. Further models and mechanisms regarding how perceptions are affected by preferences are discussed by Krueger and Dickson (1994), Pablo et al. (1996) and Mullins and Forlani (2005). At the heart of these models is the central concept from prospect theory that risks regarding gains and losses are perceived differently (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Tversky and Kahneman 1992).

4 Conclusions

As we have outlined in this chapter, existing decision theories cannot account for the typical characteristics of entrepreneurial decisions (multiple sources of risk, partial control, and endogenous risk). Our theory of mixed control and compound-risk perception framework make three key contributions. First, we explicitly combine efficacy and control beliefs into a formal model of risk perception and account for the moderating effect of control on the relationship between efficacy and expected outcomes. Second, we show that the three-dimensionality of self, others, and chance should be incorporated not only into control beliefs but also into efficacy beliefs. Control beliefs describe the extent to which different sources of risk affect outcomes and efficacy beliefs describe the expectations associated with these sources. Third, we augment our static view with a dynamic perspective and explain how risk perceptions can dynamically change over time and contexts, depending on the evolution of efficacy and control beliefs. In summary, our framework can explain more heterogeneity in entrepreneurial behavior than previous models and can therefore be applied in research and practice to better understand, improve, and increase the entrepreneurial performance of individuals and organizations.

Beyond these three explicit contributions, our chapter has the potential to provide theoretical and empirical support for other model and theories of entrepreneurship. For example, our model is complementary to the alertness model of opportunity recognition from Gaglio (1997) (see also Gaglio and Katz 2001), which proposes that entrepreneurs need to be alert to opportunities, have necessary skills (i.e., efficacy), and be able to extract a gain (i.e., control). In the mythical example related by Brännback and Carsrud (2008: 69), this system includes not only the Thor, the entrepreneur or self, but also Jormungander, the government official or powerful other. Our model, however, would suggest that Brännback and Carsrud should also consider adding Loki, a mischievous Norse deity, and the Norns, the Norse demigoddesses of destiny, to their Nordic tale of entrepreneurship.

There is, of course, room for future research. Our theory of mixed control is only one among other building blocks of a theory of entrepreneurial decision making. The question for antecedents of those control and efficacy beliefs that form the core of the theory of mixed control and the question how the perceived risk finally affects an entrepreneurial decision need to be addressed in much more detail. For instance, Harper (1998) argues that four factors within the institutional framework influence control beliefs: constitutional rules (political, legal, and economic system), operating rules (nature of economic policies), normative rules (cultural and social attitudes and norms), and characteristics of the family and educational environment during the development phase in an individual’s life. For a more detailed discussion of antecedents of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, we refer the reader to Chapter 11.

To empirically test the theory, adequate measurement instruments have to be developed. It is a well-established belief that task-specific measures of self-efficacy (Bandura 1997) and locus of control (Furnham 1986; Spector 1988) are more reliable than general beliefs and measures in specific outcomes. Therefore, general measures of efficacy and control beliefs, for example, those used by Urbig (2008) and Urbig and Monsen (2009) in testing the theory of mixed control in a general context, need to be refined for more reliable use in the entrepreneurship context. In the entrepreneurship literature, for the measurement of entrepreneurial efficacy beliefs (see, for example, Baum et al. 2001; Chen et al. 1998; De Noble et al. 1999; Forbes 2005), there are relatively well-established instruments. However, a corresponding set of entrepreneurial control beliefs has not yet attained a correspondingly broad degree of acceptance (see, for example, Bonnett and Furnham 1991). Future research should, therefore, focus on the development and integrated testing of multidimensional efficacy and control belief measures that are more specific to the context and activities of entrepreneurship.

References

Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD (1978) Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 87: 49–74

Adler PS, Kwon S-W (2002) Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review 27: 17–40

Ajzen I (2002) Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–683

Astebro T, Thompson P (2007) Entrepreneurs: Jacks of All Trades or Hobos? (p. 33). Florida International University, Department of Economics, Working Papers: 0705

Bandura A (1982) The psychology of chance encounters and life paths. American Psychologist 37: 747–755

Bandura A (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman, New York

Bandura A (1998) Exploration of fortuitous determinants of life paths. Psychological Inquiry 9: 95

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 1–26

Baron RA (1998) Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing 13: 275–294

Baron RA (2004) The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship's basic "Why" questions. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 221–239

Baum JR, Locke EA, Smith KG (2001) A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal 44: 292–303

Bernardo AE, Welch I (2001) On the evolution of overconfidence and entrepreneurs. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 10: 301–330

Bernoulli D (1738) Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis. In: Commentarri academiae sdentiarum imperialis petropolitanae, tomus v. Translated by Louise Sommer as "Expositions of a new theory on the measurement of risk," Econometrica (Jan. 1954) 22: 23–26.

Bonnett C, Furnham A (1991) Who wants to be an entrepreneur? A study of adolescents interested in a young enterprise scheme. Journal of Economic Psychology 12: 465

Brännback M, Carsrud A (2008) Do they see what we see? A critical nordic tale about perceptions of entrepreneurial opportunities, goals and growth. Journal of Enterprising Culture 16: 55–87

Brockner J, Higgins ET, Low MB (2004) Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 203

Busenitz LW, Barney JB (1997) Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing 12: 9–30

Camerer C, Lovallo DAN (1999) Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. American Economic Review 89: 306–318

Chen CC, Greene P, Gene Crick A (1998) Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers. Journal of Business Venturing 13: 295–316

Choi YR, Lévesque M, Shepherd DA (2008) When should entrepreneurs expedite or delay opportunity exploitation? Journal of Business Venturing 23: 333–355

Cobb CW, Douglas PH (1928) A theory of production. American Economic Review 18(1, Supplement): 139–165

Cromie S (1987) Motivations of aspiring male and female entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational Behavior 8: 251

Crossan M, Cunha MP, Vera D, Cunha J (2005) Time and organizational improvisation. Academy of Management Review 30: 129–145

Day L, Maltby J (2005) "With good luck": Belief in good luck and cognitive planning. Personality & Individual Differences 39: 1217–1226

De Noble AF, Jung D, Ehrlich SB (1999) Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. In: Reynolds PD (ed) Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Babson College, Babson Park, MA

DeTienne DR, Shepherd DA, De Castro JO (2008) The fallacy of "Only the strong survive": The effects of extrinsic motivation on the persistence decisions for under-performing firms. Journal of Business Venturing 23: 528–546

Fehr E, Schmidt K (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 817–868

Felton J, Gibson B, Sanbonmatsu DM (2003) Preference for risk in investing as a function of trait optimism and gender. Journal of Behavioral Finance 4: 33

Fernández-Ballesteros R, Díez-Nicolás J, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Bandura A (2002) Determinants and structural relation of personal efficacy to collective efficacy. Applied Psychology: An International Review 51: 107

Forbes DP (2005) The effects of strategic decision making on entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 29: 599–626

Forlani D, Mullins JW (2000) Perceived risks and choices in entrepreneurs' new venture decisions. Journal of Business Venturing 15: 305

Furnham A (1986) Economic locus of control. Human Relations 39(1): 29

Gaglio CM (1997) The Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification Process, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago.

Gaglio CM, Katz JA (2001) The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics 16: 95

Gatewood EJ, Shaver KG, Gartner WB (1995) A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing start-up behaviors and success at venture. Journal of Business Venturing 10: 371

Gatewood EJ, Shaver KG, Powers JB, Gartner WB (2002) Entrepreneurial expectancy, task effort, and performance. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 27: 187–206

Gist ME (1987) Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Academy of Management Review 12: 472–485

Gist ME (1989) The influence of training method on self-efficacy and idea generation among managers. Personnel Psychology 42: 787–805

Gist ME, Mitchell TB (1992) Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review 17: 183–211

Goodie AS, Young DL (2007) The skill element in decision making under uncertainty: Control or competence? Judgment and Decision Making 2: 189–203

Harper DA (1998) Institutional conditions for entrepreneurship. In: Koppl R (ed) Advances in Austrian Economics, vol. 5. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Hatch MJ (1998) Jazz as a metaphor for organizing in the 21st century. Organization Science 9: 556–557

Hatch MJ (1999) Exploring the empty spaces of organizing: How improvisational jazz helps redescribe organizational structure. Organization Studies 20: 75–100

Heath C, Tversky A (1991) Preference and belief: Ambiguity and competence in choice under uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 4: 5–28

Henahan D (1988, January 29, Friday) Music: The Cleveland. The New York Times, Section C, p. 36, Column 31, Weekend Desk

Higgins ET, Shah J, Friedman R (1997) Emotional responses to goal attainment: Strength of regulatory focus as moderator. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 72: 515–525

Hmieleski KM, Corbett AC (2008) The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. Journal of Business Venturing 23: 482–496

Janney JJ, Dess GG (2006) The risk concept for entrepreneurs reconsidered: New challenges to the conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing 21: 385–400

Judge TA, Erez A, Bono JE, Thoresen CJ (2003) The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology 56: 303–331

Judge TA, Locke EA, Durham CC (1997) The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Research in Organizational Behavior 19: 151

Judge TA, Locke EA, Durham CC, Kluger AN (1998) Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 17–34

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47: 263–292

Keh HT, Foo MD, Lim BC (2002) Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 27: 125–148

Kilka M, Weber M (2001) What determines the shape of the probability weighting function under uncertainty? Management Science 47: 1712–1726

Knight FH (1921) Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Houghton Mifflin, New York

Krueger NF (2003) The cognitive psychology of entrepreneurship. In: Acs ZJ, Audretsch DB (eds) Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction, vol. 1. Springer, New York

Krueger NF, Dickson PR (1994) How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decision Sciences 25: 385–400

Krueger NF, Reilly MD, Carsrud AL (2000) Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing 15: 411–432

Kuratko DF, Hornsby JS, Naffziger DW (1997) An examination of owner's goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management 35: 24–33

Levenson H (1974) Activism and powerful others: Distinctions within the concept of internal-external control. Journal of Personality Assessment 38: 377–383

Levenson H (1981) Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance. In: Lefcourt HM (ed) Research with the Locus of Control Construct, vol. 1. Academic Press, New York

Levenson H, Miller J (1976) Multidimensional locus of control in sociopolitical activists of conservative and liberal ideologies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 33: 199–208

Lévesque M (2004) Mathematics, theory, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 743–765

Logan MS, Ganster DC (2005) An experimental evaluation of a control intervention to alleviate job-related stress. Journal of Management 31: 90–107

Logan MS, Ganster DC (2007) The effects of empowerment on attitudes and performance: The role of social support and empowerment beliefs. Journal of Management Studies 44: 1523–1550

Lopes LL (1987) Between hope and fear: The psychology of risk. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 20: 255–295

Lopes LL, Oden GC (1999) The role of aspiration level in risky choice: A comparison of cumulative prospect theory and sp/a theory. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 43: 286–313

Machina MJ (1989) Dynamic consistency and non-expected utility models of choice under uncertainty. Journal of Economic Literature 27: 1622–1668

Markman GD, Baron RA, Balkin DB (2005) Are perseverance and self-efficacy costless? Assessing entrepreneurs' regretful thinking. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26: 1–19

Miller KD (2007) Risk and rationality in entrepreneurial processes. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 57–74

Miner JB, Raju NS (2004) Risk propensity differences between managers and entrepreneurs and between low- and high-growth entrepreneurs: A reply in a more conservative vein. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 3–13

Minniti M, Bygrave W (2001) A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 25: 5

Monsen E, Boss RW (2009) The impact of strategic entrepreneurship inside the organization: Examining job stress and employee retention. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice 33: 71–104

Monsen E, Patzelt H, Saxton T (in press) Beyond simple utility: Incentive design and tradeoffs for corporate employee-entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, DOI 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00314.x

Monsen E, Saxton T, Patzelt H (2007) Motivation and participation in corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating effects of risk, effort, and reward. In: Zacharakis A (ed) Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Babson College, Babson Park, MA

Moore DA, Oesch JM, Zietsma C (2007) What competition? Myopic self-focus in market-entry decisions. Organization Science 18: 440–454

Mullins JW, Forlani D (2005) Missing the boat or sinking the boat: A study of new venture decision making. Journal of Business Venturing 20: 47–69

Norton WI, Jr., Moore WT (2006) The influence of entrepreneurial risk assessment on venture launch or growth decisions. Small Business Economics 26: 215–226

Pablo AL, Sitkin SB, Jemison DB (1996) Acquisition decision-making processes: The central role of risk. Journal of Management 22: 723–746

Palich LE, Bagby DR (1995) Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing 10: 425

Parker SC (2006) Learning about the unknown: How fast do entrepreneurs adjust their beliefs? Journal of Business Venturing 21: 1–26

Peterson C, Maier SF, Seligman MEP (1993) Learned Helplessness: A Theory for the Age of Personal Control. Oxford University Press, New York

Puri M, Robinson DT (2007) Optimism and economic choice. Journal of Financial Economics 86: 71–99

Rotter JB (1966) Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External Locus of Control of Reinforcement. Psychological Monographs 80(1, Whole No. 609)

Sarasvathy SD (2001) Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review 26: 243–263

Schaubroeck J, Lam SSK, Jia Lin X (2000) Collective efficacy versus self-efficacy in coping responses to stressors and control: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 512–525

Schaubroeck J, Merritt DE (1997) Divergent effects of job control on coping with work stressors: The key role of self-efficacy. Academy of Management Journal 40: 738–754

Schindehutte M, Morris M, Allen J (2006) Beyond achievement: Entrepreneurship as extreme experience. Small Business Economics 27: 349–368

Schoemaker PJH (1982) The expected utility model: Its variants, purposes, evidence and limitations. Journal of Economic Literature 20: 529–563

Seligman MEP (1991) Learned Optimism. A. A. Knopf, New York

Shepherd DA, Krueger NF (2002) Cognition, entrepreneurship and teams: An intentions-based model of entrepreneurial teams’ social cognition. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 27: 167–185

Simon M, Houghton SM, Aquino K (2000) Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. Journal of Business Venturing 15: 113–134

Sitkin SB, Pablo AL (1992) Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review 17: 9–38

Sitkin SB, Weingart LR (1995) Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Academy of Management Journal 38: 1573–1592

Spector PE (1988) Development of the work locus of control scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology 61: 335–340

Spreitzer GM (1995) Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal 38: 1442–1465

Starmer C (2000) Developments in non-expected utility theory: The hunt for a descriptive theory of choice under risk. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 332

Steel P, König CJ (2006) Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review 31: 889–913

Thomas KW, Velthouse BA (1990) Cognitive elements of empowerment: An "Interpretive" Model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review 15: 666–681

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1992) Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5: 297–323

Urbig D (2008) Beliefs of One’s Own Performance, Social Support, and Luck: A Short Measure of Generalized Self-, Other-, and Chance-Efficacy. Jena Economic Research Papers Working Paper JERP #2008-020

Urbig D, Monsen E (2009) Optimistic, but not in Control: Life-Orientation and the Theory of Mixed Control. Jena Economic Research Papers Working Paper JERP #2009-013

Weber EU, Milliman RA (1997) Perceived risk attitudes: Relating risk perception to risky choice. Management Science 43: 123

Wilson F, Kickul J, Marlino D (2007) Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice 31: 387–406

Wu B, Knott AM (2006) Entrepreneurial risk and market entry. Management Science 52: 1315–1330

Zhao H, Seibert SE, Hills GE (2005) The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 1265–1272

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Monsen, E., Urbig, D. (2009). Perceptions of Efficacy, Control, and Risk: A Theory of Mixed Control. In: Carsrud, A., Brännback, M. (eds) Understanding the Entrepreneurial Mind. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 24. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0443-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0443-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4419-0442-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-4419-0443-0

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)