Abstract

Titan, after Venus, is the second example in the solar system of an atmosphere with a global cyclostrophic circulation, but in this case a circulation that has a strong seasonal modulation in the middle atmosphere. Direct measurement of Titan's winds, particularly observations tracking the Huygens probe at 10°S, indicate that the zonal winds are mostly in the sense of the satellite's rotation. They generally increase with altitude and become cyclostrophic near 35 km above the surface. An exception to this is a sharp minimum centered near 75 km, where the wind velocity decreases to nearly zero. Zonal winds derived from temperatures retrieved from Cassini orbiter measurements, using the thermal wind equation, indicate a strong winter circumpolar vortex, with maximum winds of 190 m s −1 at mid northern latitudes near 300 km. Above this level, the vortex decays. Curiously, the stratospheric zonal winds and temperatures in both hemispheres are symmetric about a pole that is offset from the surface pole by ~4°. The cause of this is not well understood, but it may reflect the response of a cyclostrophic circulation to the offset between the equator, where the distance to the rotation axis is greatest, and the seasonally varying subsolar latitude. The mean meridional circulation can be inferred from the temperature field and the meridional distribution of organic molecules and condensates and hazes. Both the warm temperatures near 400 km and the enhanced concentration of several organic molecules suggest subsidence in the north-polar region during winter and early spring. Stratospheric condensates are localized at high northern latitudes, with a sharp cut-off near 50°N. Titan's winter polar vortex appears to share many of the same characteristics of isolating high and low-latitude air masses as do the winter polar vortices on Earth that envelop the ozone holes. Global mapping of temperatures, winds, and composition in the troposphere, by contrast, is incomplete. The few suitable discrete clouds that have been found for tracking indicate smaller velocities than aloft, consistent with the Huygens measurements. Along the descent trajectory, the Huygens measurements indicate eastward zonal winds down to 7 km, where they shift westward, and then eastward again below 1 km down to the surface. The low-latitude dune fields seen in Cassini RADAR images have been interpreted as longitudinal dunes occurring in a mean eastward zonal wind. This is not like Earth, where the low-latitude winds are westward above the surface. Because the net zonal-mean time-averaged torque exerted by the surface on the atmosphere should vanish, there must be westward flow over part of the surface; the question is where and when. The meridional contrast in tropospheric temperatures, deduced from radio occultations at low, mid, and high latitudes, is small, ~5 K at the tropopause and ~3 K at the surface. This implies efficient heat transport, probably by axisymmetric meridional circulations. The effect of the methane “hydrological” cycle on the atmospheric circulation is not well constrained by existing measurements. Understanding the nature of the surface-atmosphere coupling will be critical to elucidating the atmospheric transports of momentum, heat, and volatiles.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Zonal Wind

- Planetary Boundary Layer

- Very Long Baseline Interferometry

- Meridional Circulation

- Middle Atmosphere

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

13.1 Introduction

Planetary atmospheres are nonlinear dynamical systems that resist easy analysis or prediction. While theoretical studies ranging from “simple” scaling to general circulation models (GCMs) are critical tools for developing a conceptual understanding of how an atmosphere works, these must be closely tethered to observations. The range of possibilities is too rich and complex to do otherwise. The study of extraterrestrial planetary atmospheres has traditionally drawn on the much richer body of work on the terrestrial atmosphere, but Earth is only one realization. Much of the excitement in studying planetary atmospheres is to avail oneself of the large-scale natural laboratories that other worlds provide and examine the response of atmospheres to different sets of external factors (e.g., surface or internal rotation, solar forcing, internal heat fluxes). Trying to reconcile the observed behavior of atmospheres to different forcing factors is an important step to achieving a deeper insight into the physical processes that govern it.

In the mix of available natural planetary laboratories, Saturn's giant moon Titan offers an intriguing blend. In several aspects, it resembles Earth. Its atmosphere is primarily *****N 2, and its surface pressure is about 50% larger than Earth's. After ****N 2, the most abundant constituent is not ***O 2 but ****CH 4 . Photo- and electron-impact dissociation of **CH 4 and N 2 leads to the irreversible production of more complex organic molecules that either condense and precipitate or else form the photochemical smog that enshrouds Titan. There is evidence for an analog to a hydrological cycle in Titan's troposphere, involving CH 4, not H 2 O . Its middle atmosphere (i.e., stratosphere and mesosphere) has strong circumpolar winds in winter, with cold polar temperatures, condensate ices, and anomalous concentrations of several gases. This is reminiscent of the ozone holes on Earth. There are differences, too. Titan is much colder than Earth, and the radiative response of its atmosphere is much longer. For this reason, thermal tides probably do not play an important role in Titan's lower and middle atmosphere, but gravitational tides may, induced by Titan's eccentric orbit about Saturn. Titan is a much slower rotator than Earth: its “day” is 15.95 terrestrial days. In this regard, it is more like Venus, another slow rotator, and it provides the second example of an atmosphere with a global cyclostrophic wind system, i.e., the atmospheric winds whip around the body in much less time that it takes the surface to rotate by 360°.

This chapter reviews the dynamic meteorology of Titan's lower and middle atmosphere, i.e., its troposphere, stratosphere, and mesosphere (Fig. 13.1), particularly drawing on the Cassini-Huygens data that have been acquired and analyzed to date. Section 13.2 briefly reviews the radiative and dynamical time-scales in Titan's atmosphere. Section 13.3 discusses Titan's temperatures and zonal winds, derived from Voyager, ground-based, and Cassini-Huygens measurements. The zonally averaged temperatures and mean zonal winds are coupled by the thermal wind equation. Meridional winds (Section 13.4) can be inferred more indirectly from the temperature field, as well as from quasi-conserved tracer gases and from the distribution of condensates; the Huygens probe also provided in situ measurements at 10°S. Section 13.5 focuses on the energy and momentum exchange between the surface and atmosphere and the structure of Titan's planetary boundary layer. Atmospheric waves, particularly gravitational tides, are the subject of Section 13.6. They are of interest because they can transport zonal momentum over large distances and, because their horizontal and vertical propagation depends on the thermal stability and wind structure of the mean atmosphere, they are also useful probes of atmospheric structure. Section 13.7 summarizes the current understanding of Titan's general circulation, both conceptually and by the success of GCMs in simulating Titan's atmospheric behavior. Finally Section 13.8 concludes by summarizing key questions concerning Titan's meteorology and near-term prospects for addressing them. Earlier reviews of Titan's dynamic meteorology that may be of interest can be found in Hunten et al. (1984), Flasar (1998a, b), Flasar and Achterberg (2009), and Tokano (2009).

Vertical profile of temperature at 15°S from Cassini CIRS mid- and far-infrared spectra obtained during northern winter. The solid portions of the profile indicate altitudes where the spectra constrain the temperature retrieval. The upper portion is from the spectral region of the v4 band of CH 4 at 7.7 μ m, using both nadir- and limb-viewing geometry (illustrated at top; nadir viewing denotes the situation in which the line of sight intersects the surface); the lower portion is from far-infrared spectra near 100μm, where pressure-induced N 2 absorption dominates, using only nadir-viewing geometry. The dashed portions of the profile are not well constrained by the spectra and are essentially initial guesses, based on temperatures retrieved from the Voyager radio occultations (after Flasar et al. 2005)

13.2 Radiative and Dynamical Time Constants

Before discussing measurements of meteorological variables on Titan and their interpretation, it is helpful to briefly discuss the notion of radiative relaxation times and dynamical turnover times, which will be used repeatedly in the ensuing discussion.

13.2.1 Radiative

Titan's atmosphere is an interesting entity: its radiative response varies by several orders of magnitude as one moves vertically through the atmosphere. The early analysis of Voyager data indicated that Titan's radiative relaxation time — the time over which its temperature relaxes to a radiative equilibrium profile from an initial disturbance, extending over an altitude that is typically on the order of a pressure scale height — was quite large in the troposphere, ~130 years (Smith et al. 1981), and decreased with altitude to a value ~1 year in the upper stratosphere near 1 mbar (Flasar et al. 1981) (see Hunten et al. 1984 and Flasar 1998b for more discussion). More recent radiative flux measurements by the Huygens Probe Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR) have indicated a time constant on the order of 500 years in the lower troposphere (Tomasko et al. 2008; Strobel et al. 2009, Ch. 10, Fig. 10.5). Two conclusions follow. The first is that, since the radiative relaxation times in Titan's troposphere and middle atmosphere are much longer than its day (15.95 days) divided by 2 πFootnote 1, one does not expect solar-driven diurnal effects, e.g., thermal tides, to be very important. The second is that radiative time scales in the upper stratosphere are much smaller than Titan's year (29.5 years) divided by 2 π, so there should be a strong response to the seasonal modulation of solar heating. The measurements discussed in the following sections bear this out. Given the very long radiative time constant in the troposphere, Flasar et al. (1981) suggested that seasonal variations there would be very weak. However, this neglected any effects that seasonal variation in surface temperatures would have in coupling to the atmosphere. The heat capacity in the annual skin depth of the surface is much smaller than that corresponding to the lowest scale height of atmosphere (Tokano 2005), particularly in the absence of global oceans or widespread deep lakes. Enough solar radiation (~10%, McKay et al. 1991) makes it through the atmosphere to the surface to produce a seasonal variation in its temperature. Coupling of the surface to the atmosphere through thermally driven convection heats the lower atmosphere seasonally. GCM model simulations generally display a strong seasonal component (Section 13.7). From GCM simulations, Tokano (2005) has concluded that the thermal inertias of some plausible surface materials is low enough that a diurnal variation is possible.

13.2.2 Dynamical

For global-scale flow, the dynamical time scale is the turnover time, the horizontal scale of a circulation cell, divided by the horizontal velocity. For the axisymmetric meridional circulations thought to be important on Titan, the horizontal scale is on the order of a planetary radius (Section 13.7). The turnover times can be comparable to a season. When the dynamical time scale is longer than the radiative time scale, there can be an additional, dynamical inertia that acts to retard the atmosphere's relaxation to the radiative equilibrium state. For example, temperatures obtained by the Voyager infrared measurements indicated a north—south asymmetry at 1 mbar (Flasar and Conrath 1990) . This was curious, because the Voyager season was shortly after northern equinox, and the radiative relaxation time was relatively short. Bézard et al. (1995) suggested that this might result from a hemispheric asymmetry in the opacities for solar and thermal radiation. Flasar and Conrath (1990) alternatively suggested a dynamical origin. They noted although temperatures could rapidly relax to an equilibrium configuration radiatively, they were coupled to the zonal wind fields by the thermal wind equation (Section 13.3). Hence to reach the equilibrium state angular momentum also had to be transported from the northern hemisphere to the southern. The dynamical turnover time for achieving this transport was comparable to a season on Titan, implying that the stratospheric temperatures and zonal winds would always lag the solar heating, despite the small radiative relaxation time.

13.3 Temperatures and Zonal Winds

Any study of atmospheric dynamics and meteorology is predicated on having measurements of temperatures, winds, and gaseous constituents and other tracers of motions in three dimensions. Spatially resolved observations of Titan only began with spatially resolved imaging by Pioneer 11 during its flyby in 1979 (Tomasko and Smith 1982), and in earnest with the Voyager 1 and 2 close passages in 1980 and 1981 a few months after its northern spring equinox. The Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe, observing Titan in northern winter, have provided the best resolution and global coverage to date. Images from the Hubble Space Telescope and imaging using ground-based adaptive optics have provided important information on Titan's state between the two missions, albeit at lower spatial resolution. Finally, much of what we have learned about Titan's zonal winds and their seasonal modulation before Cassini-Huygens has come from Earth-based observations, including stellar occultations, heterodyne spectroscopy, and correlation spectroscopy.

Temperature, wind, and composition fields are often cast in terms of zonal averages, i.e., averages around a latitude circle. These mean variables define the general circulation, and it is its seasonal and longer-term climatological variations that one seeks to understand. Often the coverage in longitude is not very extensive and surrogate representations must be used, e.g., retrieved variables at a specific longitude or a few longitudes. For instance, spectra from nadir-viewing observations by the Cassini Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) cover latitude and longitude extensively, and temperatures and composition retrieved from this data can be used to construct true zonal averages. On the other hand, CIRS limb-viewing observations are more sparsely distributed in longitude, and true zonal averages are not possible for these spectra. Fortunately, available evidence, including the CIRS nadir spectra, indicate that zonal variations in temperatures, derived winds, and composition on Titan are usually smaller than meridional variations (see, e.g., Teanby et al. 2008) . Hence the ensuing discussion of meteorological variables in this section and the next (Section 13.4) will often be in terms of zonally averaged quantities, even though the measurements themselves have not always provided suffi-cient data to construct these averages.

13.3.1 Temperatures

Chapter 10 (Strobel et al. 2009) discusses the vertical structure of temperature in some detail, so comments here are brief. Figure 13.1 illustrates that the thermal structure of Titan's lower and middle atmosphere, at least at low latitudes, is remarkably reminiscent of Earth's, with a well-defined troposphere, stratosphere, and mesosphere. Titan's temperatures are much lower than Earth's, because of its greater distance form the sun, and the pressure scale height — ranging from 15 to 50 km — is much larger than on Earth (5–8 km), mainly because the gravitational acceleration on Titan–1.3 m s −2 at the surface — is much smaller. In fact the large scale height means that Titan's atmosphere is much more extended than most planetary atmospheres in the solar system. The 10μbar level in the mesosphere, for example, roughly corresponds an altitude of 400 km, a sizeable fraction of Titan's 2,575-km radius. Near-infrared images of Titan from the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) show methane fluorescence up to ~730 km altitude (Baines et al. 2005) .

The vertical profile of temperature is primarily important as a measure of the stability of an atmosphere, i.e., how stable an atmosphere is to vertical motions and whether waves can propagate and how they are refracted by the mean flow when they propagate vertically and horizontally. However, it is the lateral variations in temperature that serve as diagnostics of the departure of an atmosphere from purely radiative response and of the structure of meridional circulations (Section 13.4). Measuring horizontally resolved thermal structure has really only been achieved by the close-up reconnaissances of Voyager and Cassini-Huygens. The ingress and egress of the single Voyager 1 radio-occultation sounding were both in the equatorial region, although at nearly diametrically separated longitudes. Little variation in the troposphere and lower stratosphere was evident (Lindal et al. 1983, Lellouch et al. 1989) . The Voyager thermal-infrared spectrometer (IRIS) obtained reasonable latitude coverage during the Voyager 1 flyby, but coverage in longitude was limited to two strips on the day and night sides, nearly 180° apart. Moreover, the IRIS spatial resolution was limited: spectra had to be averaged in latitude bins, typically 15° or larger, in order to obtain an adequate signal-to-noise ratio (Flasar et al. 1981) . Only in the upper stratosphere~1 mbar (1 mbar = 1 hPa = 100 Pa) could temperatures be retrieved on isobars, by inverting the observed radiances in the v4 band of CH 4 near 1.300 cm −1 (7.7μm) and assuming that the gas was uniformly distributed with latitude. Temperatures at high northern latitudes were ~12–20 K colder than at the equator; temperatures in the south were flatter between the equator and 50°, where they began to fall off toward the pole. Neither pole was well observed. Other wavelength regions near 200 cm −1 and 530 cm −1 probed the tropopause and surface, respectively. Little meridional variation was evident. Temperature variations near the tropo-pause were ~1 K, and the equator-to-pole contrast at the surface was ~2–3 K. The difficulty was that these differences were estimated from brightness temperatures; the unknown and heterogeneously distributed opacity sources at these wavelengths precluded direct retrieval of temperatures.

Cassini-Huygens, with a more capable array of in situ and remote-sensing instruments, has greatly extended global mapping of atmospheric temperatures at high spatial resolution. For the Cassini spacecraft, this is ensured in no small part by virtue of its being in orbit about Saturn and returning to Titan repeatedly, where its proximity allows good spatial resolution. Preliminary analysis of several radio-occultation soundings at mid and high southern latitudes and high northern latitudes, together with the descent temperature profile from the Huygens Atmospheric Structure Instrument (HASI; see Chapter 10), indicate that the meridional variation of temperatures in the troposphere is small, ~5 K at the tropo-pause and ~3 K near the surface. Most of the global mapping of atmospheric temperatures is from CIRS thermal-infrared spectra, but these do not permit retrieval of temperatures in the lowest 1½ scale heights (Flasar et al. 2004) .

Most of the retrieved temperature maps to date have been from CIRS nadir- and limb-viewing in the mid-infrared, using the observed radiances in the v4 band of CH 4 as a thermometer to probe the atmosphere above the 10-mbar level. This is a classic case of going after the low-lying fruit first. The far-infrared radiances, which include pressure-induced N 2 absorption and the rotational lines of CH 4, probe lower in the atmosphere and are more affected by aerosol and condensate opacity, which require more careful analysis to retrieve temperatures. Figure 13.2 (top) depicts the meridional cross section of temperatures in Titan's middle atmosphere, retrieved from limb and nadir spectra. The vertical range over which there is information on temperature is 5 millibar −3 microbar, except in the colder regions at high northern winter latitudes, where the information content dies away at the 2 mbar level (Achterberg et al. 2008a) . Given these caveats, the most dramatic aspect of the temperature field is the behavior at high northern latitudes. Below the 0.1-mbar level, the north polar region is colder than at lower latitudes. This is expected, because it is the region of polar night, and the radiative relaxation time is relatively short (Section 13.2). The temperature contrast is 20–30 K. However, higher up in the stratosphere, the high northern latitudes become the warmest part of Titan's atmosphere, with temperatures exceeding 200 K. Titan's polar night does not extend to these higher altitudes. At winter solstice, its north pole is tilted by ~26.7° away from the sun, so the maximum height of shadow, in the absence of atmospheric scattering, is (~70 μbar). Given the thick condensate hazes that are observed at high northern latitudes during the winter and early spring, it is conceivable that radiative heating may contribute to the warm anomaly observed, but this has not been studied. It may also have a dynamical origin, and this is discussed in Section 13.4.

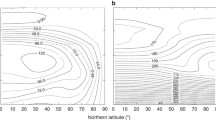

Top panel. Meridional cross section of temperature (K) from CIRS limb and nadir spectra in the mid infrared. Bottom panel. Zonal winds (m s -1) computed from the thermal wind equation (13.7) with the winds at 10 mbar set to uniform rotation at four times Titan's rotation rate. Positive winds are eastward. The parabolic curves correspond to surfaces parallel to Titan's rotation axis (after Achterberg et al. 2008a)

The figure indicates that the stratopause, the altitude of the maximum temperature marking the boundary between the stratosphere and the mesosphere, varies with latitude. It is lowest near the equator, where it is at the 70-μbar level. It rises slightly toward the south pole, but its elevation increases dramatically toward the north pole,~10 μbar. This is a far greater scale-height variation than seen on Earth (see, e.g., Andrews et al. 1987) .

The longitude coverage afforded by CIRS limb soundings is limited, and nadir mapping in the middle infrared has provided most of the information on the zonal structure of temperatures, between 0.5 and 5 mbar. An unexpected result of the mapping was the discovery that the pole of symmetry of the stratospheric temperatures is tilted approximately 4° relative to the IAU definition of the polar axis, which is normal to Titan's orbit about Saturn. The spectral decomposition of the zonal temperature structure relative to the IAU pole indicated a strong wavenumber-1 component (one wavelength around the latitude circle) at most latitudes, and it was strongest at the latitudes having the strongest meridional gradients in temperature. Moreover, the phase of the wavenumber-1 component (i.e., the longitude of the warmest temperatures) remained nearly constant with latitude in each hemisphere, flipping by 180° across the equator. Since both poles are cooler than low latitudes near 1 mbar (Fig. 13.2), this strongly suggested a global tilt of the atmospheric pole of symmetry. By recalculating the zonal variances for an ensemble of new pole positions, the tilt was determined by minimizing the global variance of the temperatures from their zonal means (Achterberg et al. 2008b) . Figure 13.3 displays the 1-mbar temperatures; the offset of the axis of symmetry from the IAU pole position is more evident in the northern hemisphere, where the meridional gradients are larger. In the northern hemisphere the tilt of the pole is toward the sun, but about 76°W of the solar direction. The temperatures about the tilted axis are nearly axisymmetric at most latitudes: the standard deviation of the zonal variation is not much greater than that propagating from the CIRS instrument noise. Because of the thermal wind equation, the winds tend to flow along isotherms (see Section 13.3.2.1), and thus are also centered about the offset pole. The 4° tilt is an order of magnitude greater than the recent measurement of the tilt of the rotation pole of the solid surface (Stiles et al. 2008) .

Polar projection maps of retrieved temperatures at the 1-mbar level. The northern hemisphere is shown on the left and the southern hemisphere on the right . The color-coded temperature scale in kelvins is shown at the bottom . The superposed grid represents latitude and west longitude in a sun-fixed frame with the longitude of the sub-solar point at 180°W, such that the sun direction is towards the left and right edges of the figure. Temperature contours are plotted at intervals of 5 K in the northern hemisphere, and 1 K in the southern hemisphere. The fitted axis of symmetry is indicated by white and black crosses (+) in the north and south, respectively (after Achterberg et al. 2008b)

13.3.2 Zonal Winds

The likely presence of strong zonal winds on Titan had been inferred from infrared observations during the Voyager 1 flyby in November 1980. A distinct pole-to-equator latitudinal contrast in temperature was revealed, varying from ΔT͌ 3 K at the surface to ΔT͌20 K in the stratosphere (Flasar et al. 1981) . The meridional gradients and the thermal wind equation implied an atmosphere that globally superrotates, analogous to that observed on Venus. To date zonal winds calculated from temperature and pressure fields have provided the most detailed picture of the global wind field. However, these suffer from ambiguities with respect to the wind direction and the need for a (often unknown) boundary condition when the zonal winds are derived from temperatures. Hence direct methods, based on observing the Doppler shifts of molecular lines, tracking discrete clouds, or tracking the descent of the Huygens probe, provide invaluable tie points for winds inferred from temperature and pressure.

13.3.2.1 Indirect Methods

The shape of the zonally averaged pressure and temperature fields is linked to the mean zonal winds. For steady, inviscid, axisymmetric flow, the balance is (see, e.g., Holton 1979; Leovy 1973):

where P is pressure, ρ is atmospheric density, Ω = 4.56×10−6 s −1 is Titan's angular rate of rotation, u is the zonal velocity, r is the radius (surface radius plus altitude), Λ is latitude, and i⊥ is a unit vector normal to Titan's rotation axis. V is the total potential (gravitational plus centrifugal) for a frame rotating at Titan's rotation rate; Titan is such a slow rotator that the gravitational component dominates:

i r is a unit vector in the radial direction from Titan's center, and g is the gravitational acceleration. The radial projection of (13.1) is the familiar hydrostatic equation:

where the velocity terms involving u in (13.1) have been neglected in the projection, to a good approximation. The horizontal projection along lines of constant meridian yields the gradient wind relation:

Alternatively, the gradient wind relation can be written in terms of the gravitational potential variation along isobars:

The balance (13.4 or 13.4′) generally holds for zonally averaged variables to a good approximation when the lateral scale is large compared to a scale height. Hence, (13.1), as well as (13.3) and (13.4), can be viewed as a hydrostatic balance law in two dimensions (in height and latitude), with the centrifugal acceleration associated with the zonal winds adding vectorially to the gravitational acceleration. A possible exception is near the equator, where the left-hand side of (13.4) becomes small because of the trigonometric term. For instance, on Earth the mean lateral convergence of momentum by eddies — not included in (13.1) or (13.4) — in the intertropical convergence zone is known to be important. Usually one does not know a priori how close to the equator the gradient wind relation fails, or even if it does: (13.4) can remain valid if (∂P / ∂Λ) V ∝ sin Λ across the equator. In practice, errors in the measured variables preclude application of (13.4) as Λ→0, because the errors in u from the propagation of the errors on the right-hand side magnify inversely as sinΛ or \(\sqrt {\sin \Lambda } \).

In rapidly rotating bodies, like Earth, Mars, and the outer planets, the first term on the left-hand side of (13.4, 4′), linear in u, dominates, and the equation reduces to geostrophic balance, in which the meridional gradient in pressure is balanced by the Coriolis force. For slow rotators, like Venus, the second term, quadratic in u, dominates and one has cyclostrophic balance, in which the pressure gradient is balanced by the centrifugal force associated with the zonal winds themselves. Titan is also a slow rotator, and in its middle-atmosphere the winds greatly exceed Titan's equatorial surface velocity (Ωa͌ 11.7 m s −1, where a = 2,575 km is Titan's radius); cyclostrophic balance is again dominant. Because the centrifugal force is quadratic in u, the direction of the zonal wind is not determined from the gradient wind relation. For the relation to hold at all, however, the pressure at constant height (or, equivalently, the potential along isobars) must decrease poleward. Hence cyclostrophic flow requires an equatorial bulge. Central flashes observed at Earth during occultations of stars by Titan have provided information on the shape of the isopycnal (i.e., constant-density) surfaces near the 0.25-mbar level (Hubbard et al. 1993; Bouchez 2003; Sicardy et al. 2006) . Without too large an error, one can take these surfaces to be isobars (see Hubbard et al. 1993) and apply the gradient wind equation (13.4'). Figure 14.11 (Chapter 14; Lorenz et al. 2009) illustrates the zonal winds derived from some of these occultations.

Historically Titan's cyclostrophic winds were first inferred from temperature data using the thermal wind equation (Flasar et al. 1981; Flasar and Conrath 1990) . Operating on equation (13.1) with the curl (Δ×):

For axisymmetric flow, gradients around latitude circles vanish, and only the zonal component in (13.5) is nonzero. With the assumption of the perfect gas law and the neglect of spatial variations in the bulk composition (both valid except in the lower troposphere), this gives:

where z ǁ is the coordinate parallel to the planetary rotation axis and R is the gas constant. With (13.3), (13.6) reduces to:

Unlike the gradient wind equation, the thermal wind equation (13.7) requires a boundary condition, a specification of u . Often one specifies u on a lower boundary. Zonal winds derived from (13.7) are illustrated in the bottom panel of Fig. 13.2. The salient features are the strong circumpolar wind, the polar vortex in the (northern) winter hemisphere, and the weak zonal winds in the summer hemisphere, where meridional contrasts in temperature are weaker.

For a thin atmosphere,

where Λ0 is an average (constant) latitude. With this 0 approximation eq. (13.7) reduces to the usual thermal wind equation:

or in ln P coordinates,

On Titan the relation (13.9, 9′) fails at low latitudes, because the approximation (13.8) breaks down, and the integration of the thermal wind equation (13.7) to solve for the zonal winds must be along cylinders concentric with Titan's rotation axis (Flasar et al. 2005) . For example, the 0.4-mbar isobar is approximately 130 km higher in altitude than the 10-mbar isobar. A cylindrical surface that intersects the equator at 10 mbar intersects the 0.4-mbar level at 17° latitude. These intersections (at northern and southern latitudes) lie on the parabola depicted in Fig. 13.2 tangent to the 10-mbar level. Outside this parabola, it is sufficient to apply a boundary condition at the 10-mbar level to integrate the thermal wind equation (13.7). However, cylinders intersecting the latitudes and pressure-levels within this parabola do not intersect the 10-mbar level. In this region, one must specify a boundary condition on the winds at higher altitudes, for example in the equatorial plane. However, the latter is a priori unknown. In Fig. 13.2 the winds within the 10-mbar parabola were interpolated along isobars. Although the winds at 10-mbar and lower are not well determined glo bally, this probably does not pose a critical problem in the winter northern hemisphere, as shown in Fig. 13.2. This is because the thermal wind equation implies that the winds increase markedly with altitude, and the zonal winds in the upper stratosphere are dominated by the thermal wind component above the 10-mbar level, i.e., the integral of the right hand side of (13.7). Since the u 2 term dominates the left-hand side of (13.7), it is not sensitive to the 10-mbar boundary condition away from the boundary. At mid and high latitudes in the southern hemisphere, the predicted thermal winds are weaker, and they are more sensitive to what is happening at the lower boundary.

Figures 13.2 and 14.11 (Chapter 14) indicate a significant seasonal variation in the stratospheric zonal winds, with the strongest velocities in the winter hemisphere. This is expected, because of the seasonal variation in temperatures (Section 13.3.1). The zonal-wind and temperature fields are coupled through the thermal wind equation, and hence changes in temperatures imply concomitant changes in the zonal winds. However, radiative processes do not transport angular momentum. It is mass motions, eddies, and waves that effect this transport and affect the nature of the seasonal variation (Sections 13.2 and 13.4).

13.3.2.2 Direct Methods

13.3.2.2.1 Doppler Line Shifts

One technique offering a direct determination of the wind speed and direction is to measure the differential Doppler shift of atmospheric spectral features as the field-of-view moves from east limb to west limb. Infrared heterodyne observations of Titan's ethane emission at 12μm have been performed on three separate occasions (Kostiuk et al. 2001, 2005, 2006). Although the instrument field of view covered a significant portion of Titan's disk, the measurements consistently provided evidence for eastward winds with velocities exceeding 200 m s −1 at heights near 200 km (1 mbar), but with a relatively large uncertainty (Fig. 13.4). Luz et al. (2005, 2006) have performed similar observations over a wide range of wavelengths from 420 to 620 nm using a high performance spectrograph at the Very Large Telescope. Eastward wind with velocities of about 45–60 m s −1 were inferred at 170–200 km altitude, the primary height range of the emission features used to determine the differential Doppler shift between east and west limb. The technique has also been extended to the millimeter wavelength range, which it is sensitive to higher altitudes, depending on the specific spectral feature measured. Moreno et al. (2005) found the atmosphere to be superrotating at a speed of 160 ± 60 m s −1 (centered at 300 km altitude) and 60 ± 20 m s−1 (450 km), respectively.

Upper abscissa . Titan zonal wind velocity determined from measurements at different heights. The DWE profile from the surface to 145 km (Bird et al. 2005) is shown for comparison. In decreasing order of height the highest two data points (triangles ) are the mm-observa-tions from Moreno et al. (2005) . The diamonds show results from the heterodyne IR observations of Kostiuk et al. (2001, 2005, 2006) . Luz et al. (2005, 2006) reported results from broadband UVES observations (lower bounds — squares ). Two representative points (asterisks) are included from the CIRS zonal wind retrieval at 15°S (Flasar et al. 2005), adjusted to be consistent with the DWE-determined wind velocity of 55 m/s at 10 mbar. Lower abscissa . The temperature profiles are the solid curve from Yelle et al. (1997) and the dashed curve from Flasar et al. (2005) (reproduced from Kostiuk et al. 2006)

13.3.2.2.2 Cloud Tracking

The measurement of winds from tracking of cloud motions has been a valuable technique on all of the giant planets and Venus. Unfortunately, Titan has not been kind to cloud trackers. Its clouds are infrequent and are typically ephemeral, lasting less than a few hours in many cases. Yet this potentially remains one of the few existing means to probe the zonal winds globally in the troposphere.

Prior to the arrival of Cassini-Huygens, disk-average ground-based observations at near infrared wavelengths in 1998 suggested the presence of reflective clouds, thought to be CH 4, covering less than 7% of Titan's disk and located at roughly 15 ± 10 km altitude (Griffith et al. 2000) . Observations the following year indicated a high degree of temporal variability, with the inferred clouds dissipating in as little as 2 h. Yet they were observed over several nights. Radiative transfer modeling indicated the clouds were near 27 km altitude and covered only 0.5% of the disk, about 1% of the cover typically seen on Earth. Later observations, using adaptive optic systems that resolved Titan's disk (Brown et al. 2002; Roe et al. 2002) showed transient clouds concentrated near the south pole, which was in early summer. The authors interpreted the location and variability of the clouds as evidence of moist convection involving CH 4 condensation. Later observations in October 2004, shortly after Cassini's orbit insertion, showed an 18-fold increase in cloud brightness (Schaller et al. 2006a) near the south pole, with a factor-of-two change in brightness over 24 h. Earlier observations from 1996 to 1998, using speckle interferometry at the W. M. Keck Telescope (Gibbard et al. 2004), had also detected clouds near the south pole, supporting the notion that this was a long-term seasonal activity driven by the warm surface at the pole in late spring and early summer.

Later observations revealed clouds at temperate latitudes. With adaptive optics techniques at the Gemini North 8-m telescope, Roe et al. (2005) found tropospheric clouds clustered between 37° and 44°S on three of thirteen nights in 2003–2004. Unlike the nearly circular nature of the south polar clouds, these clouds were filamentary, extending eastward more than 1,000 km, about 30° in longitude, while only spanning a few degrees in latitude. These clouds were mostly clustered near 350°W, which suggested a geographical tie, associated perhaps with geysers or cryovolcanoes that could inject bursts of CH 4 vapor into the atmosphere. Subsequent observations by the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS; Porco et al. 2005; Turtle et al. 2009) and the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS; Griffith et al. 2005; Rodriguez et al. 2009) failed to corroborate the preferential location on the side of Titan facing Saturn; in fact the VIMS and ISS data indicate that the clouds in this latitude belt are nearly uniformly distributed in longitude (Rodriguez et al. 2009; Turtle et al. 2009) . Other mechanisms, involving meridional transports of CH 4, have been suggested (Griffith et al. 2005) .

Observations of the motions of a few well-behaved long-lived (~1 day) clouds, led to the first cloud-tracked wind velocities from ground-based observations. Tracking a temperate latitude feature on 2–3 October 2004, Roe et al. (2005) deduced a velocity of 8 m s −1 eastward and 3 m s −1 northward, which seemed consistent with the expected direction and magnitude of tidal winds (Section 13.6.1). Bouchez and Brown (2005) tracked clouds over several nights near the south pole and found no significant motion, placing 3- σ limits of 4 m s −1 on zonal (i.e., east–west) motion, and 2 m s −1 on meridional (north—south) motion.

The Cassini ISS and VIMS instruments both observed the south polar cloud during the first (distant) Titan flyby (T0) on 2 July 2004. Both sets of observations indicated sluggish eastward motions less than 4 m s -−1 at high southern latitudes (Porco et al. 2005; Baines et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2006) . VIMS observed four cloud features, the most prominent being a 700-km wide feature centered at 88 ° S (Baines et al. 2005) . Three smaller clouds were observed within 16° of latitude of this main feature, ranging in size from 65 to 170 km in diameter. The prominent south polar cloud was observed for 13 hours, enabling a measurement of a zonal wind speed of 0.5 ± 3.3 m s −1 (Brown et al. 2006), slightly favoring an eastward motion. Two other cloud features, one at 74°S and the other at 78°S, showed slow zonal wind speeds of 0.9 ± 3.9 and 2.3 ± 2.0 m s -−1, respectively, both also consistent with eastward motions. Meridional motions were imperceptible.

The ground-based adaptive optic imagery of the south polar clouds by Schaller et al. (2006a) in October 2004, several weeks prior to the first Cassini cloud observations, also led to zonal velocity estimates. From two pairings of nights, Schaller et al. found zonal wind velocities of 2 ± 3 and 0 ± 4 m s −1, consistent with the VIMS and ISS south polar cloud results. From VLT/NACO and CFHT/PUEO adaptive optics imagery acquired in 2002–2004, Hirtzig et al. (2006) measured an average south polar zonal wind speed of 3 ± 2 m s −1 . Subsequent observations between December 2004 and April 2005 showed the nearly complete disappearance of the south polar cloud (Schaller et al. 2006b), although VIMS observations have indicated periodic outbursts occurring almost every nine months from December 2004 through June 2007 (Rodriguez et al. 2009) . These outbursts diminished in strength and persistence with time as the Titan equinox approached, perhaps consistent with the march of the summer season and the change in meridional transport by the global circulation.

ISS observations during the first Titan encounter (T0) showed the fastest cloud feature tracked so far: 34 ± 13 m s −1 eastward at 38°S. Eastward winds were also measured for 9 of 11 other clouds. During the third Titan flyby (Tb) in December 2004, VIMS images showed a long cloud streak extending over 25° in longitude near 41°S (Baines et al. 2005) . Attempts to derive reliable zonal velocities with time lapsed observations were unsuccessful. Spectral analysis of four discrete cloud features embedded within this cloud streak by Griffith et al. (2005) showed rapid changes in cloud top altitude over 35 min, with one cloud top rising 14 km in altitude during that time, from 21 to 35 km, corresponding to updraft velocities near 10 m s −1 . They also concluded that high cloud centers dissipate or descend to the ambient cloud level near 10 km within an hour, consistent with the fall velocity of millimeter-sized raindrops expected for Titan (Toon et al. 1988; Lorenz 1993) . Thus, temperate latitude cloud streaks can be highly dynamic and changeable, with altitudes that can vary on short timescales. Consequently, they are not typically reliable indicators of wind velocities.

13.3.2.2.3 Huygens Doppler Wind Experiment (DWE)

The Huygens probe has provided the most detailed vertical profile of Titan's zonal wind. After its heat shield was jettisoned and the first parachute deployed, the probe descended for nearly 150 min before impacting the surface near 10°S. During this descent phase, the lateral motion of the probe was close to that of the ambient winds. The DWE instrumentation, consisting of an atomic rubidium oscillator in the probe transmitter to assure adequate frequency stability of the radiated signal and a similar device in the orbiter receiver to maintain the high frequency stability, was implemented only on one of the radio links on the Cassini spacecraft, Channel A (2,040 MHz). Whereas the other link, Channel B (2,098 MHz), functioned flawlessly during the entire mission, the Channel A receiver was not properly configured during the probe relay sequence. All data on this link, including the probe telemetry and the planned DWE measurements, were lost. Fortunately, the primary DWE science objective, a vertical profile of winds on Titan, was largely recovered by ground-based tracking of the Channel A signal at large radio telescopes (Bird et al. 2005; Folkner et al. 2006) .

During the DWE design phase it was recognized that Earth-based Doppler measurements could be combined with the orbiter Doppler measurements to reconstruct both the zonal and meridional components of the Huygens probe motion during descent (Folkner et al. 2004) . Ideally, the horizontal projection of the ray paths from Huygens to Cassini and to the Earth should be perpendicular, but the 160° separation for the actual experiment geometry was still considered adequate for the calculation. A fundamental uncertainty in the Earth-based measurement was whether the received power from the Huygens carrier signal would be sufficient to support near real-time reduction of the data, or if a more extensive data processing effort, augmented with additional information from the telemetry sub-bands, would be required, as it was in the case of the ground-based detection of the Galileo Probe signal at Jupiter (Folkner et al. 1997) . Despite the considerably greater distance, the probability of detecting the Huygens signal from Titan was deemed slightly more favorable than for the case of the Galileo Probe, because of the substantially higher Huygens transmitter antenna gain toward Earth. Moreover, significant residual carrier power in the Huygens signal was expected, compared to no residual carrier for the Galileo Probe. Ground-based support was solicited in a multi-facility observation proposal submitted to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), specifically for observation time at the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) in West Virginia, and at eight antennas of the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), and to the Australia Telescope National Facility (ATNF) for observations at the Parkes Radio Telescope and several other smaller Australian antennas.

A second Earth-based experiment designed to provide ultra-precise sky positions of the Huygens probe using the Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) technique (Pogrebenko et al. 2004; Witasse et al. 2006) was conducted in parallel with the ground-based DWE observations. The results of the VLBI experiment, which enlisted a total of 17 radio telescopes in Australia, China, Japan, and the USA, are still under review.

The topocentric sky frequencies of the Huygens Channel A carrier signal recorded at GBT and Parkes are shown in Fig. 13.5. The time resolution is typically one point each 10 seconds, for which the measurement error is of the order of 1 Hz, corresponding to an uncertainty in the line-of-sight velocity of 15 cm s −1 . The Earth-based signal detection at GBT coincides with the initial transmission from Huygens at t0 + 45s, where t0 is the designated start of the descent. Also indicated in Fig. 13.5 are the times of impact and loss of link to Cassini. The Huygens probe was still transmitting from Titan's surface when Titan descended below the minimum elevation limit in the terrestrial sky and the signal could no longer be tracked at the Parkes antenna.

Topocentric sky frequencies of the Huygens Channel A carrier signal recorded at the GBT and Parkes facilities. A constant value of 2,040 MHz, the nominal transmission frequency, has been subtracted from all measurements, so that the plotted data points are equivalent to the total signal Doppler shift from transmitter to receiver. The upper time scale is Spacecraft Event Time; the lower scale is minutes past the nominal start of mission at t0 = 09:10:20.76 SCET/UTC. The Earth's rotation is primarily responsible for the lower recorded frequency at GBT (near end of track) with respect to Parkes (near start of track ). The small gaps between data segments and the larger post-landing gap correspond to intervals when the radio telescopes were pointed to celestial reference sources near Titan for calibration of the simultaneously conducted VLBI experiment. A single larger gap of 26 minutes is present in the interval between the end of the observations at GBT and the start of observations at Parkes. The times of impact at t0 + 147m 50s (11:38:11 SCET/UTC) and loss of link to Cassini at t0 + 220m 3s (12:50:24 SCET/UTC) are indicated. The Parkes tracking pass ended at t0 + 341m 37s (14:51:58 SCET/UTC) with the Huygens probe still transmitting from the Titan surface (after Bird et al. 2005)

A Doppler signature for the change from the main parachute to a smaller drogue parachute may be seen in Fig. 13.5 at t0 + 15m . At this instant, the suddenly larger descent velocity produces an abrupt decrease in the received frequency which closely follows that predicted by simulation. An additional decrease in the observed frequency comes from the rapidly decreasing zonal wind that continues through the parachute exchange event (Fig. 13.6). Similarly, a nearly discontinuous frequency increase marks the impact on the surface at 11:38:11 SCET/UTC. The magnitude of this positive jump in frequency, 26.4 ± 0.5 Hz, reflects the abrupt change in vertical velocity from about 5 m/s to zero.

Zonal wind velocity during the Huygens mission. The winds above 12 km are eastward (positive zonal wind), but a significant reduction in the wind speed is observed at altitudes in the interval from 60 to beyond 100 km. The interval associated with the parachute exchange, during which the probe lags the actual wind, starts at an altitude of 111 km and lasts until 104 km. A monotonic decrease in the zonal wind speed was recorded from 60 km down to the end of the GBT track at 10:56 SCET/UTC. The Parkes observations could not begin until 11:22 SCET/UTC, thereby excluding wind determinations in the height region from roughly 12 km down to 4.5 km. By this time Huygens was in a region of weak westward winds that again turned eastward about 1 km above the surface (adaptation and update of Bird et al. 2005)

With precise knowledge of the geometry, the raw measurements of sky frequency yield the line-of-sight motion of the transmitter in the Titan frame of reference. The vertical motion of the Huygens probe, which slowly decreased with decreasing altitude, was measured in situ by the HASI pressure sensors (Fulchignoni et al. 2005) and the Huygens radar altimeters. The available consolidated measurements were processed iteratively by the Huygens Descent Trajectory Working Group (DTWG) to produce a series of continually improving Huygens trajectories referenced to Titan (Atkinson et al. 2007; Kazeminejad et al. 2007) . The results presented here are based on the descent velocity of the final DTWG data set #4, released in May 2007. Based on knowledge of the Huygens point of atmospheric entry following separation from Cassini, and integrating the trajectory through the entry phase with the help of accelerometer measurements (Colombatti et al. 2008), the DTWG also supplied the nominal coordinates of the Huygens probe in latitude (10.33 ± 0.17°S), longitude (196.08 ± 0.25°W), and altitude (154.8 ± 8.5 km) at the start of descent t0.

Two key assumptions about the horizontal motion of the probe were applied to simplify the problem of determining the probe velocity during descent. The first of these is that the horizontal drift of the probe follows the horizontal wind with a negligible response time. The actual response time for the Huygens descent system is estimated to be roughly 30–40 s in the stratosphere, decreasing to 3–5 s in the lowest 10 km (Atkinson et al. 1990; Bird et al. 1997) . This may be fulfilled only marginally during the early minutes of the descent and is violated briefly during the deployment of the second parachute (altitudes: 111–104 km). Barring any unanticipated parachute aerodynamics, the probe should be capable of roughly following the wind again at all altitudes below 100 km. A simple modeling analysis of the difference between the zonal wind speed and the zonal probe speed concluded that the probe was lagging the wind by up to a maximum of 7% above 40 km and that Huygens was an unreliable wind gauge only during the 2-min interval following the parachute exchange. The second assumption, that the drift in the meridional (north—south) direction is negligible, is based primarily on theoretical considerations that imply dominance of the zonal (east—west) atmospheric circulation (Flasar 1998b) . The Huygens trajectory reconstructed from landmark positions determined from the DISR images below 40 km was found to have a small, but nonzero, meridional drift (Karkoschka et al. 2007) . The poor projection of the north— south motion onto the line-of-sight to Earth results in a negligible effect on the observed Doppler shift and thus the zonal wind retrieval.

Small, nearly time-invariant corrections were applied for the effect of special relativity (−7.5 Hz, whereby the minus sign means a red shift), as well as the effects of general relativity associated with the Sun (18.2 Hz), Saturn (−0.7 Hz), Earth (1.4 Hz) and Titan (−0.08 Hz). A detailed discussion of these corrections may be found in Atkinson (1989) . Propagation corrections to the Doppler measurements from ray refraction in the neutral and ionized intervening media (Titan, interplanetary, and Earth) have been estimated and found to be negligible. Temperature inversions, which can produce a distinct Doppler signature in the received frequency for a conventional occultation geometry with tangential ray propagation, are not effective for the case of radio propagation from Huygens to Earth because the signal propagates upward out of the atmosphere and thus parallel to any strong radial gradients. A final small correction of + 10.0 Hz was applied to the absolute transmission frequency by invoking the constraint that Huygens remains stationary on Titan's surface after landing. This residual is within the error limits of the pre-launch unit-level calibration of + 9.2 Hz determined for the specific DWE oscillator unit used to drive the Huygens Channel A transmitter.

The variation of the zonal wind as a function of time, derived from the data in Fig. 13.5 using an algorithm developed for the Huygens-Cassini link (Dutta-Roy and Bird 2004), but adapted for the Huygens-Earth link, is shown in Fig. 13.6. More precisely, the quantity plotted in Fig. 13.6 is the horizontal velocity of Huygens in the east direction with respect to the surface of Titan (positive value indicating the eastward direction). The time-integrated wind measurement from t 0 yields an estimate for the longitude of the Huygens landing site on Titan, 192.33 ± 0.31°W, which corresponds to an eastward drift of 3.75 ± 0.06° (165.8 ± 2.7 km) over the duration of the descent. This propagation error associated with the wind retrieval has been estimated and is found to be insignificant because the Doppler shift depends only weakly on the probe's position during the entire descent.

The variation of the zonal wind with altitude and pressure level is shown in Fig. 13.7 in comparison with the Titan engineering wind model and envelopes based on Voyager temperature data (Flasar et al. 1997) . The measured profile is in rough agreement with the upper level wind speeds anticipated by the engineering model and generally eastward above 12 km altitude, within the region tracked from GBT. Assuming this local observation is representative of conditions at this latitude, the eastward wind speed profile provided the first in situ confirmation of the atmospheric superrotation anticipated from the Voyager temperature data. Moreover, the large ratio of the measured winds to Titan's equatorial rotation speed (Ωa ͌ 11.7 m s −1, where Ω = 4.56 × 10 −6 s −1 and a = 2,575 km are Titan's rotation rate and radius, respectively) validates the condition of cyclostrophic pressure balance. Over the lower altitudes (<5 km) tracked by Parkes, Fig. 13.7 indicates that the winds had shifted westward, but again turned eastward over the lowest 1 km.

Titan zonal wind height profile. The zonal wind derived from GBT and Parkes observations are compared with the model and envelopes proposed by Flasar et al. (1997) . With the possible exception of the region above 100 km, where the wind fluctuations are greatest, the zonal flow was found to be generally weaker than those of the model. The wind shear layer in the height range between 60 and beyond 100 km was unexpected and still lacks a generally accepted explanation (adaptation and update of Bird et al. 2005)

The most striking departure of the measured profile from the engineering model is the region of weak wind, sandwiched above and below by regions of strong positive and negative wind shear, where the zonal wind reaches a minimum of 4 m s −1 at about 75 km altitude. The broad minimum in zonal wind speed between 60 and 100 km, which can be seen in Fig. 13.5 as a symmetrical dip in frequency over the interval between t0 + 20 m and t0 + 30 m, is interpreted as a real property of Titan's atmospheric dynamics. This feature of Titan's wind profile is unlike that measured by any of the Doppler-tracked probes in the atmosphere of Venus (Counselman et al. 1980) . The slow zonal wind occurs in the stratospheric region of strongest static stability, i.e., the largest vertical increase in temperature, but there is currently no generally accepted explanation of it. The thermal wind equation implies that the vertical shear in the derived zonal wind profile would be associated with strong, oppositely directed, meridional temperature gradients. Such sharp gradients might be connected with an interface region between different meridional circulation cells, but supporting observations are scarce. The slow wind layer occurs above the maximum altitude (30–40 km) for corroboration from surface feature tracking with DISR images (see below). The simultaneous VLBI tracking of Huygens had inadequate temporal resolution to verify the slow wind region (L.I. Gurvits et al., personal communication, 2009). Independent evidence in support of the strong vertical gradient in zonal wind was found in the Channel B signal amplitude measurements on the Cassini orbiter, which revealed a distinct tilt of the Huygens probe during these time intervals (Dzierma et al. 2007) . The only Cassini observations that may help resolve the uncertainty in the critical height range from 60 to 100 km would be meridional temperature variations derived from either CIRS far-IR or RSS (Radio Science Subsystem) occultation data.

13.3.2.2.4 Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR)

The descent trajectory of the Huygens probe has been used to derive the probe ground track and extract the implied wind speed as a function of altitude (Tomasko et al. 2005) . The diverse landscape near the landing site facilitated the reconstruction of the trajectory based on a sequence of images by DISR of surface landmarks. The probe moved horizontally about 2° north of east on average from the release of the first parachute to an altitude of about 50 km (Karkoschka et al. 2007) . Thereafter, the motion turned slightly to about 5° south of east between 30 and 20 km altitude (Fig. 13.8, top panel). Between 15 and 6.5 km the probe moved to the east-northeast and experienced a sharp turn towards northwest (Fig. 13.8, bottom panel). Finally its motion turned counterclockwise through almost 180° at 0.7 km altitude towards the southeast or south-southeast down to the surface. No images were available during the last 200 m of the descent, so the surface wind was constrained by the direction of the parachute, which was not visible in the surface images acquired after the landing. The wind was most likely blowing towards azimuth 160° (20° east of south) with 0.3 ± 0.1 m s −1. Thus the meridional wind was stronger than the zonal wind near the surface and the meridional wind changed direction at several altitudes. Throughout the descent the meridional wind speed varied between about ±1 m s −1 . The zonal winds derived from the DISR images are generally in agreement with the DWE results discussed above. In contrast to DWE, however, DISR was able to distinguish between meridional and zonal motion and could thus follow the wind direction reversals that occurred in the last minutes of the descent.

Top panel. The Huygens trajectory relative to the landing site, starting at 40 km altitude. The numbers denote altitudes in km. Solid dots indicate the position of Huygens every full kilometer of altitude. Bottom panel. The same, but starting at 13 km. Trajectories derived from DISR data alone and the DTWG determination, are both shown. The circles and squares along the curves indicate altitude at 500-m intervals. The DTWG results were based on DISR data for meridional drifts but on DWE data for zonal drifts. Below 12 km, the DTWG trajectory determination is up to ~600 m further east than that from DISR. The discrepancy results from the interpolation used over a gap in the DWE data between 12 and 5 km (after Karkoschka et al. 2007)

13.4 Meridional Circulations

Zonal-mean meridional and vertical motions are important for transporting angular momentum, energy, and constituents. Although eddy transports can be important, use of the transformed Eulerian-mean velocities incorporates many of these eddy fluxes into the mean circulation when motions are quasi-adiabatic and steady (Andrews et al. 1987) . In Earth's middle atmosphere, the transformed Eulerian-mean circulation is equivalent to the Lagrangian circulation, which follows the motions of conserved quantities, to a good approximation (Dunkerton 1978) . There is generally no simple diagnostic relation like that between zonally averaged temperatures or pressures and mean zonal winds. One must either obtain in-situ measurements with sufficient accuracy and coverage to determine the meridional and vertical motion fields, or else one must use variables that can serve as tracers. These include, for example, gaseous constituents with lifetimes on the order of the turnover time of the meridional circulation, temperature variations along isobars, or potential vorticity (see, e.g., Flasar 1998a for more discussion of this conserved quantity) to infer the meridional circulation.

13.4.1 Temperatures

Flasar et al. (1981) had noted that the IRIS determination of the meridional distribution of surface temperatures, which amounted to ~3 K, was not consistent with just a radiative response to solar heating. Cassini radio occultation soundings, which cover several latitudes from 74°S to 74°N, also show a contrast of only a few kelvins in the lower troposphere. The radiative solution to the annual average solar heating would imply an equator-to-pole contrast of 15 K, far larger than observed. Flasar et al. noted that a simple Hadley circulation, annually averaged, could transport sufficient heat to reduce the meridional gradient with surprisingly small meridional velocities, ~0.04 cm s −1.

As noted earlier, one of the most striking features of the middle atmosphere are the elevated temperatures above the north (winter) pole at the 10-μbar level. While diabatic processes involving the thick condensate hazes over the pole may be at play, adiabatic heating associated with subsidence over the pole is likely to be substantial. This is what happens in Earth's middle atmosphere (see, e.g., Andrews et al. 1987). The winter and summer seasons are marked by a cross-equatorial circulation with ascent at high summer latitudes and subsidence at high winter latitudes, within the polar vortex. The adiabatic heating over the winter pole is critical in heating the mesosphere, and indeed the mesopause over the winter pole is markedly warmer than over the summer pole because of this. Titan GCM studies are also consistent with subsidence over the winter pole (see, e.g., Hourdin et al. 2004) . The lowest-order balance is between adiabatic heating and radiative relaxation:

where w is the transformed Eulerian-mean vertical velocity, T is temperature, C p is the specific heat, T eq is the radiative equilibrium temperature, and τr is the radiative relaxation time; all quantities are zonal averages. T-T eq ~ 25 K at 10 μbar seems reasonable given the contrast between the north pole and low latitudes. At a given temperature τr should slowly fall off with altitude, because the decrease in mass per scale height with altitude is offset to some degree by the reduced emissivity of CH 4 , CH 2, and CH 6, the principal infrared gaseous coolants (Flasar et al. 1981) . Using τr ~ 3 × 107 s, appropriate to 170 K and 1 mbar, one obtains w ~ −1 mm s −1 (Achterberg et al. 2008a). At 200 K, τr is a bit smaller and ǀ wfǀ corresponding larger.

13.4.2 Gas Composition

So far, the study of the meridional distribution of gases has primarily been of the organic constituents in the stratosphere. Figure 13.9 depicts the meridional variation of several organic molecules, retrieved from Cassini and Voyager thermal-infrared spectra (Teanby et al. 2006; Coustenis et al. 2007; Coustenis and Bézard 1995). All the nitriles (HCN , HC 3 N, C 2 N 2) and several hydrocarbons (C 3 H 4, C 4 H 2, C 6 H 6, C 2 H 4 in the spring) exhibit enhanced concentrations at high northern latitudes. Most of the formation of these species, following the breakup of N 2 and CH 4, occurs higher up in the atmosphere. With most organics condensing in the lower stratosphere, one expects the concentration to increase with altitude, toward the source region (Chapter 10). Limb sounding at mid-infrared wavelengths with Cassini CIRS (Vinatier et al. 2007; Teanby et al. 2007) indicates that this typically is the case. Subsidence at high northern latitudes could naturally lead to an enhanced concentration of these species at the 1–10-mbar level. Polar enhancement of the more abundant organics, e.g., C 2 H 6 and C 2 H 2, is less, because the vertical gradients of their concentra-tion are smaller. Teanby et al. (2009) have noted that on average the enhancements of the various constituents scale inversely with their photochemical lifetimes. In the presence of polar subsidence, this would naturally result if the rate of increase of concentration with altitude scaled inversely with the photochemical lifetime. This seems plausible, if the mean vertical profiles of individual constituents results from a competition between vertical mixing and photochemical decay: the constituents with the shortest lifetimes will have the steepest vertical gradients in their concentration. The observed enhancements of the organics and their plausible interpretation in terms of subsidence suggests an absence of strong lateral mixing of air masses within the polar vortex with those outside by eddies or waves; this isolation also occurs on Earth at the winter pole. Analysis of limb data by Teanby et al. (2008) indicates a fairly complex structure within the winter vortex (Fig. 13.10). There seem to be areas of depletion of HCN, HC 3 N , and C 4 H 2 within the polar vortex at 300 km altitude (~0.1 mbar). What is going on has not really been worked out, but Titan's polar vortex structure seems to be as rich in structure as Earth's ozone holes.

Meridional profiles of organic gases and CO 2from nadir-viewing observations in the mid infrared in northern spring (Coustenis and Bézard 1995) and in northern winter (Coustenis et al. 2007). The spectral emission features used to retrieve the profiles typically have maxima in their contribution functions at a level of several mbar, with a spread of several scale heights. The values of C 2 H 6 shown in the figure should be multiplied by 0.7, owing to a recently improved determination of its spectroscopic constants (Vander Auwera et al. 2007) . (a) Cassini CIRS (2004–2005): northern winter and (b) Voyager IRIS (1980): early northern spring. Note that theabundances of HC 3 N and C 2 N 2 in (b) have been offset by a factor of 10 for clarity (after Flasar and Achterberg 2009)

Cross sections of temperature (upper left panel) and composition from CIRS mid-infrared limb sounding. Composition is given as a volume mixing ratio and the position of the observed limb profiles are denoted by the inverted triangles at the top of each plot. Contours indicate the vortex zonal wind speeds (in m s −1) derived by Achterberg et al. (2008a) and blue dashed lines show the region with the steepest horizontal potential vorticity gradient, which indicates a dynamical mixing barrier. Altitudes with low signal-to-noise or where the atmosphere becomes opaque are not plotted. Note that southern latitudes are toward the left of each panel. VMR denotes the volume mixing ratio and l is the photochemical lifetime at 300 km (after Teanby et al. 2008)

13.4.3 Aerosols and Condensates

That Titan has an enhanced haze layer over its winter pole, suggestive of organic ices, has been known since the Voyagers flew past in 1980–1981. The haze signature is evident in images of Titan throughout the ultraviolet, visible and near infrared, because the haze structure and sometimes also particle single scattering albedo differ significantly from those at lower latitudes. Some tentative identifications of organic ices have been made, but others remain unknown. Recent VIMS observations (Griffith et al. 2006) have detected a bright feature extending poleward of ~50° N, which is consistent with a dense C 2 H 6 cloud located between 30 and 50 km altitude. Voyager IRIS and Cassini CIRS spectra both exhibit broad spectral features that are suggestive of condensates (Samuelson et al. 1997, 2007; Khanna 2005; Coustenis et al. 1999), but only at high latitudes in the hemisphere that is in winter or early spring. A particularly striking broad feature centered at 221 cm −1, seen both IRIS and CIRS spectra, has yet to be identified. It may be a blend of organic ices. However, it is constricted in latitude, evident poleward of 55°N, but abruptly disappearing at 50°N and equatorward (Flasar and Achterberg 2008). This distribution does not directly provide information on meridional velocities, but it is consistent with a mixing barrier between low- and high-latitude air masses, much as occurs on Earth. It is tempting to wonder whether heterogeneous chemistry occurs on these condensates, much as it does in the terrestrial polar stratospheric clouds, but as yet there is no evidence of this.

In addition to the structure over the winter pole, there is also a more subtle hemispheric albedo asymmetry that is most noticeable in the strong methane absorption bands at 890 nm and at longer wavelengths. The boundary is displaced by about 15° from the equator. Analysis of Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images (Lorenz et al. 1997) led to the idea that hemispheric contrasts are produced by aerosol micro-physical variations in the region above 70 km altitude and mostly below 120 km altitude driven by seasonal variations in aerosol transport by winds, in agreement with (but more specific than) the view that Sromovsky et al. (1981) put forth. Karkoschka and Lorenz (1997) derived haze aerosol radii near 0.3 μm in the northern latitudes versus 0.1 μm in the south from 1995 HST images of Titan's shadow on Saturn. They assign these particle radii to different layers, the ‘detached haze’ layer at northern latitudes and the main haze layer at latitudes south of 50°S. Penteado et al. (2009) found that hemispheric variations in surface albedo and in haze optical depth and single scattering albedo at altitudes higher than 80 km account for hemispheric differences observed in Cassini VIMS spectra.

Roman et al. (2009) analyzed albedo patterns in 20 images obtained by the Cassini ISS instrument with the 890-nm methane filter (sensitive to haze above about 80 km altitude). These images reveal a haze hemispheric asymmetry with offset 3.8° ± 0.9° in latitude directed 79° ± 24° to the west of the sub-solar longitude. This result is very close to that derived by Achterberg et al. (2008b) from thermal data (Section 13.3.1) and indicates a zonal wind pattern that transports haze in accord with expectations from the thermal wind equation.

Hemispheric asymmetry in haze properties must be related to the meridional circulation but the details have not been worked out. The contrast boundary near the equator would suggest that two cells are operative in addition to a winter polar vortex. A fully coupled chemical, dynamical and haze microphysical model is needed to relate the haze observations to other processes. Some progress has been made in this area, using two-dimensional GCMs with parameterized eddy fluxes (see, e.g., Hourdin et al. 2004; Crespin et al. 2008).

13.4.4 In-situ Measurements

Section 13.3.2.2 has already discussed the use of DISR images to infer meridional motion during the Huygens probe descent (Fig. 13.8). Below 40 km, the meridional wind speed varied between about ±1 m s −1 . Near the surface the meridional wind was stronger than the zonal wind and both changed direction at several altitudes.

While the horizontal components of the atmospheric flow could be determined by the Doppler Wind Experiment and probe ground tracking, the smaller vertical component could not be separated from the trajectory by such means. However, the vertical wind along the descent trajectory of Huygens was determined from HASI accelerometer measurements combined with accurate knowledge of the atmospheric pressure and temperature profile during the Huygens descent. Mäkinen et al. (2006) solved the equation of motion of the descending probe using these data to determine the vertical wind speed. The measured vertical profile of vertical wind can be broadly subdivided into the stratosphere and troposphere (Fig. 13.11). In the entire troposphere the prevailing motion is upward, with a mean vertical speed of 5 cm s−1 and several wiggles are superposed. In contrast to the troposphere, the vertical flow in the stratosphere was found to be mostly downward, with maxima at 70 and 110 km altitude (up to 0.6 m s −1). The vertical flow around 90 km was upward (15 cm s −1). When compared with the horizontal wind profile (Bird et al. 2005; Folkner et al. 2006), the averaged zonal and vertical profiles loosely correlate with each other, the strength of the vertical wind being about 1% of that in the zonal direction.

Solid curve : vertical atmospheric velocity along the descent trajectory of the Huygens probe. Dashed curves : the error envelope. Dot-dashed curve : Zonal wind derived from the Huygens DWE, scaled down by a factor of 1/250 (after Mäkinen et al. 2006)

The large vertical velocities obtained from the probe data cannot be associated with the zonal mean flow. To see this, consider the situation near 110 km (7 mbar), where Fig. 13.11 indicates a subsidence w~ –0.5 m s -−1, and the implica tions from the heat equation balance (13.10). At this altitude \(\left({\frac{{\partial T}} {{\partial z}} + \frac{g} {{C_p }}} \right) \approx \) 1.6 K km -1 . Flasar et al. (1981) estimated the radiative relaxation times (at 10 mbar) ~3 × 10 7 s−1 × 10 8 s, where the larger value corresponds to just gaseous cooling by C2 H2, C2 H6, and CH and the smaller value includes cooling by aerosols in a simple model. More recent estimates of radiative cooling by the Huygens DISR experiment (see Chapter 10, Fig. 10.5) yield a larger value: τr ~ 3 × 10 8 s at 110 km. One can solve (13.10) for the departure of the atmospheric temperature from the radiative equilibrium solution, which scales linearly with τr. Using the smallest value, 3 × 10 7 s, leads to the estimate T-T eq ~ 24,000 K, which is so large it can be ruled out by existing data.

Could the retrieved vertical velocities be indicative of wave motions? For the simplest case of waves propagating vertically and zonally in a mean zonal wind u¯, the heat balance in adiabatic flow becomes:

where x is the zonal (east-west) coordinate, k is the zonal wavenumber, and T = ΔTexpi(kx − ωt) is assumed. The quantity ω ̂ is the (doppler-shifted) frequency of the wave relative to the background flow. For gravitational tides, which have been extensively studied (Section 13.6.1), ω ̂~ Ω ͌4.6 × 10 −6 s −1, the diurnal frequency (Tokano and Neubauer 2002; Strobel 2006; Walterscheid and Schubert 2006), which implies a diurnal amplitude ΔT ~ 175 K; this is still much too large compared to observations. Internal gravity waves may be a possibility, because they have higher frequencies. For these, Λ ̂ is bounded (see, e.g., Andrews et al. 1987) by the Brunt-Väisälä frequency,

and the Coriolis frequency, 2ΩsinΛ~10−5 s−1 . From (13.11) ΔT~1/ω̂, implying smaller temperature amplitudes, so this suggestion merits further study.

13.5 Surface-Atmosphere Coupling

13.5.1 Structure of PBL

The planetary boundary layer (PBL) is the lowermost portion of the atmosphere that is affected by surface friction. The PBL lies below the “free atmosphere,” discussed earlier (Section 13.3.2.1), where the gradient-wind balance typically holds for zonally averaged variables, at least away from the equator. The structure of the PBL controls the surface-atmosphere exchange of energy, momentum and matter, thus affecting meteorology and exogeneous geology. The first information on Titan's PBL came from the radio occultation experiment of Voyager 1, with a published altitude resolution of 0.5 km near the surface (Lindal et al. 1983) . The retrieved temperature profiles near the equator, for an assumed N 2 atmo sphere, showed a lapse rate of 1.38 K km −1 below about 3.5 km, close to the dry adiabatic lapse rate, and an abrupt drop to 0.9 K km −1 above this level. The lapse rate below 1 km in the evening profile (ingress) was slightly larger than the morning profile (egress). Hence the surface may have had a slight cooling effect on the atmosphere during the nighttime.

The first in situ investigation of the PBL structure was carried out by the Huygens probe, which landed near the equator in the morning hours (Tokano et al. 2006) . Simultaneous vertical sounding of temperature and pressure with an altitude resolution of about 10 m near the surface was used to calculate the vertical profile of potential temperature, which is a measure of the static stability (the lapse rate in temperature less the dry adiabatic lapse rate) and a major classification criterion of a PBL. The potential temperature slightly decreased with altitude in the lowest 10 m, virtually stayed constant between 10 and 300 m and increased almost monotonically with altitude above 300 m. In other words, the lapse rate was superadiabatic immediately above the surface, adiabatic in the main part of the PBL and subadia-batic outside the PBL. Thus the 300-m PBL determined by Huygens was shallower than the 3.5-km thick layer indicated by the Voyager radio occultation data.