Abstract

Alkaptonuria is a rare disorder of amino acid metabolism that causes premature large joint and spine arthropathy and cardiac valvular disease. It is characterised by elevated levels of homogentisic acid. Nitisinone (NTBC) is a benzoylcyclohexane-1,3-dione that reversibly inhibits the activity of the enzymatic step immediately prior to homogentisate dioxygenase, hence reducing the production of homogentisic acid. Thus it is thought that nitisinone might be a treatment for alkaptonuria. A side effect of NTBC therapy is elevation of plasma tyrosine levels in a manner analogous to tyrosinemia type 2, another related condition which causes a painful palmoplantar hyperkeratosis and eye pathology described as conjunctivitis and herpetic-like corneal ulceration. There are only two previous reports of NTBC causing eye symptoms in patients with alkaptonuria. Here we provide further evidence of this side effect of treatment and its resolution with cessation of NTBC. Repeat challenges with NTBC provoked symptoms, but introducing a low protein diet with low dose NTBC was successful in controlling plasma tyrosine levels and the patient remained free of symptoms when levels were below 600 μmol/L. Our patient was remarkable for the low dose of NTBC that precipitated symptoms (as little as 0.5 mg daily), and for the difficulty in proving its causation despite clinical suspicion.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Alkaptonuria is a rare disorder of amino acid metabolism that causes premature large joint and spine arthropathy and cardiac valvular disease. It is characterised by elevated levels of homogentisic acid due to autosomal recessive mutations in homogentisate dioxygenase (gene HGD; OMIM #203500; Phornphutkul et al. 2002), the third enzyme in the tyrosine metabolism pathway (Fig. 1). Homogentisic acid is further metabolised to benzoquinone acetic acid which forms a melanin-like polymer and is deposited in the connective tissue (a process known as ochronosis), leading to the major disease manifestations as well as characteristic dark discolouration of the earlobes, irises and nail beds.

Nitisinone (NTBC) is a benzoylcyclohexane-1,3-dione that reversibly inhibits the activity of the enzymatic step immediately prior to homogentisate dioxygenase, thus reducing the production of homogentisic acid. Thus it is thought that NTBC might be a treatment for alkaptonuria (Introne et al. 2011). NTBC has been used for many years in the treatment of hereditary tyrosinemia type 1, a related disorder with a metabolic block further down the tyrosine metabolism pathway at fumarylacetoacetase. A side effect of NTBC therapy is elevation of plasma tyrosine levels in a manner analogous to tyrosinemia type 2 (due to deficiency of tyrosine transaminase), a related condition which causes a painful palmoplantar hyperkeratosis and eye pathology described as conjunctivitis and herpetic-like corneal ulceration. There are only two previous reports of NTBC causing eye symptoms in patients with alkaptonuria (Introne et al. 2011; Stewart et al. 2014); here we provide further evidence of this side effect of treatment and its resolution with cessation of NTBC.

Case Description

The patient, AA, is a 21-year-old female whose diagnosis of alkaptonuria had been made when she was 5 years old. She was commenced on vitamin C from the ages of 7 until 15 years and was maintained on a mildly restricted protein diet from 13 years. Evaluation at age 21 documented an unremarkable history, with no symptoms of major joint arthropathy, and normal psychomotor development. Physical examination was likewise unremarkable (height 162 cm and weight 52 kg), and echocardiography and plain X-rays were reported as normal. Prior to NTBC therapy, the level of urinary homogentisic acid was 1,066 mmol/mol creatinine (<0.2 mmol/mol creatinine) and plasma tyrosine was 37 μmol/L (32–114 μmol/L).

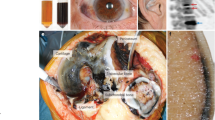

She was commenced on low dose NTBC (0.5 mg daily), and noted mild eye discomfort and occasional visual blurring 4 days later. Optometry review did not detect any abnormalities other than mild hypermetropia; her symptoms of occasional visual blurring and eye discomfort continued without increasing in severity. At 4 months of therapy the homogentisic acid level was 249 mmol/mol creatinine; tyrosine was not measured. The dose of NTBC was increased after 7 months to 1.5 mg daily. At 10 months of treatment, she noted significantly increased eye irritation, inflammation and photophobia. The level of homogentisic acid was 47.7 mmol/mol creatinine and tyrosine was 760 μmol/L. Optometry review noted corneal irritation and photosensitivity without corneal crystalline deposits or keratopathy, and antibiotics were prescribed for a presumed bacterial infection. She was advised to cease NTBC. Symptoms did not improve over 3 days and urgent ophthalmology review diagnosed blepharitis for which steroids were prescribed. Symptoms settled over 1 week and NTBC was recommenced. Symptoms rapidly recurred and repeat ophthalmology examination finally revealed corneal crystalline deposits (Fig. 2). Symptoms and tyrosine crystals resolved within days of cessation of NTBC.

A subsequent challenge with NTBC at 1 mg daily invoked mild symptoms 4 weeks after commencement, and crystals were again seen. NTBC was ceased for 2 weeks with resolution of symptoms. A further trial of NTBC at 0.5 mg daily, with natural dietary protein restricted to 40 g, supplemented with 15 g protein equivalent of tyrosine-free supplement, has resulted in plasma tyrosine levels ranging from 285 to 625 μmol/L. Over this period of 4 months the patient was almost symptom free. Mild ocular irritation which resolved without intervention over 3 days was noted by the patient around the time that plasma tyrosine level was 625 μmol/L. The subsequent tyrosine level was 461 μmol/L.

Discussion

Is there causation between tyrosine levels and ophthalmic pathology in NTBC-treated alkaptonuria? Our data from this single case report does not provide a definitive answer to this question; however, high tyrosine levels (760 μmol/L) correlated with worse symptoms in our patient. Experience in tyrosinemia type II is instructive here, as untreated patients may have levels over 1,000 μmol/L, and dietary management (low protein diet with appropriate formula supplementation) lowers levels to under 600 μmol/L with resolution of ophthalmic symptoms within days to weeks (Scott 2006).

The particular sensitivity of our patient to NTBC was surprising. Doses of 10 mg daily are being used in the SONIA-2 trial, and doses of up to 8 mg daily were tolerated in the SONIA-1 trial (Ranganath et al. 2016). Two other patients known to the authors have not had symptoms despite being on higher doses than this patient (up to 2 mg daily), and with plasma tyrosine levels of up to 800 μmol/L. It is worth noting, however, that the two previously described cases of nitisinone-induced keratopathy in alkaptonuria occurred in patients receiving relatively low doses – 2 mg daily and 2 mg on alternate days (Introne et al. 2011; Stewart et al. 2014).

This case demonstrates that subjective clinical symptoms from crystalline keratopathy may be found in the absence of crystals being seen, and at tyrosine levels elevated by relatively low doses of NTBC. We suggest that plasma tyrosine levels be monitored after first commencing NTBC, and maintained at levels of <600 μmol/L with a combination of tailored NTBC dosage and dietary management. We also suggest that ophthalmology review be instituted at first clinical ophthalmology symptoms, and consideration of NTBC dose reduction or cessation be undertaken regardless of whether signs of keratopathy are seen.

References

Introne WJ, Perry MB, Troendle J et al (2011) A 3-year randomized therapeutic trial of nitisinone in alkaptonuria. Mol Genet Metab 103(4):307–314

Phornphutkul C, Introne WJ, Perry MB et al (2002) Natural history of alkaptonuria. N Engl J Med 347(26):2111–2121

Ranganath LR, Milan AM, Hughes AT et al (2016) Suitability Of Nitisinone In Alkaptonuria 1 (SONIA 1): an international, multicentre, randomised, open-label, no-treatment controlled, parallel group, dose-response study to investigate the effect of once daily nitisinone on 24-h urinary homogentisic acid excretion in patients with alkaptonuria after 4 weeks of treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 75(2):362–367

Scott CR (2006) The genetic tyrosinemias. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 142C:121–126

Stewart RM, Briggs MC, Jarvis JC, Gallagher JA, Ranganath L (2014) Reversible keratopathy due to hypertyrosinaemia following intermittent low-dose nitisinone in alkaptonuria: a case report. JIMD Rep 17:1–6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Additional information

Communicated by: Daniela Karall

Appendices

Synopsis

NTBC used for the treatment of alkaptonuria may cause corneal crystalline keratopathy at low doses, and symptoms may be apparent prior to ophthalmic changes.

Declaration of Competing/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (SSIEM)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

White, A., C. Tchan, M. (2017). Nitisinone-Induced Keratopathy in Alkaptonuria: A Challenging Diagnosis Despite Clinical Suspicion. In: Morava, E., Baumgartner, M., Patterson, M., Rahman, S., Zschocke, J., Peters, V. (eds) JIMD Reports, Volume 40. JIMD Reports, vol 40. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/8904_2017_56

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/8904_2017_56

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-57879-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-57880-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)