Abstract

In Gilbert Hay’s 1499 Buik of Alexander, we find a striking invocation of Alexander the Great’s terrestrial grasp. After traveling through the skies in a cage carried by griffons, and sitting atop the highest mountain in the east, Alexander returns—after diverse travels through strange lands—to his army:

And tauld thame all the maner and þe wise

How he had sene the erde to Paradise,

And all þe regiouns and the wildernis,

The realmis, regiouns, and the gretest place,

And how this erde is bot ane litell thing,

And that it was bot liffing for a king.

And in his hart he copyit þe figure,

And syne gart draw it into portratoure,

And how the erde is of a figure round—

And thus was first payntit þe mappamond.1

[And told them all the manner and the nature

How he had seen the earth as far as Paradise,

And all the regions and the wilderness,

The realms, regions, and the greatest places,

And how this world is just a little thing,

And that it was but a living for a king.

And in his heart he copied the image,

And afterwards began to draw it as a picture,

And this the earth is a round figure—

And thus was first painted the map of the world.]2

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Preview

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

John Cartwright, ed., Sir Gilbert Hay’s The Buik of King Alexander the Conqueror, Vol. III, Scottish Text Society, 4th series, 18 (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1990), 161 (ll. 15613–15622).

Norman Thrower, Maps and Civilization: Cartography in Culture and Society, 3rd edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 57.

P. D. A. Harvey, “Medieval Maps: An Introduction,” in J. B. Harley and David Woodward, eds., The History of Cartography, Vol. I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 283.

P. D. A. Harvey, “Local and Regional Cartography in Medieval Europe,” in J. B. Harley and David Woodward, eds., The History of Cartography, Vol. I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 464.

Denis Wood, Rethinking the Power of Maps (New York: Guilford Press, 2010), 23.

Harvey, “Local and Regional Cartography in Medieval Europe,” 464. Field terriers are medieval and early-modern records of the ownership, arrangement, and names of fields within a township or parish. See further David Hall, “Open Fields,” in Pamela Crabtree, ed., Medieval Archaeology: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland, 2001), 355.

Trevor J. Barnes, “Spatial Analysis,” in John Agnew and David Livingstone, eds., The Sage Handbook of Geographical Knowledge (London: Sage, 2011), 381–382.

Barnes, “Spatial Analysis,” 382. For further discussion see Michael R. Curry, “Toward a Geography of a World without Maps: Lessons from Ptolemy and Postal Codes,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 95.3 (2005): 685.

David C. Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to AD. 1450, 2nd edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 279.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984), 117.

Ptolemy, “The Elements of Geography,” in Morris Raphael Cohen and Israel Edward Drabkin, eds., A Sourcebook in Greek Science (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948), 163. It might seem counterproductive to cite Ptolemy’s definitions of topos and choros while decrying his outlined practice of geos, but I do not think that it is. While Ptolemy’s geographic framework was adopted as the dominant mode of representation, the one most suited to the expanding physical and bureaucratic world of sixteenth-century Europe, this in no way invalidates his observations regarding other forms of representation. Ptolemy views the three modes as purpose-specific, coexisting in order to fulfill different representational functions.

Bertrand Westphal, Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces, trans. Robert T. Tally Jr. (New York: Palgrave, 2011), 58.

Giuseppe Tardiola, Atalante fantastico del medioevo (Rome: Rubeis, 1990), 14; qtd. in Westphal, Geocriticism, 58.

David Woodward, “Reality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World Maps,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 75.4 (1985): 519.

Naomi Kline, Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2001)

Scott D. Westrem, The Hereford Map (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001).

Alain Ballabriga, Les fictions d’Homere: L’invention mythologique et cosmographique dan l’Odyssee (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1998), 109; qtd. in Westphal, Geocriticism, 80.

Helen Cooper, The Medieval Romance in Time: Transforming Motifs from Geoffrey of Monmouth to the Death of Shakespeare (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 70.

Nicholas Howe, Writing the Map of Anglo-Saxon England: Essays in Cultural Geography (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 3.

See Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953), Chapter 6.

Thomas Malory, Le Morte Arthur: The Winchester Manuscript, ed. Helen Cooper (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 146.

Kyng Alisaunder survives in three manuscripts, including the Auchinleck MS, and is a Middle English translation of Thomas of Kent’s late twelfth-century Le roman de toute chevalerie; see David Salter, Holy and Noble Beasts (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2001), 114, note 10.

John Scattergood, “Validating the High Life in Of Artour and of Merlin and Kyng Alisaunder,” Essays in Criticism 54.4 (2004): 348.

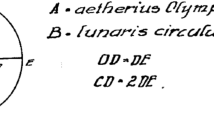

All citations from romance are from G. V. Smithers, ed., Kyng Alisaunder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952). For a similar example of a textual T-and-O map, see the geographical verses in the fifteenth-century BL MS Royal D. xii: This world ys delyd al on thre/Asia, Affrike and Europe/ … /Suria and the lond of Judia/These bene in Asya (in

J. Halliwell and T. Wright, eds., Reliquiae Antiquae [London, 1845], 1: 271–272).

Jacques le Goff, Medieval Civilization, 400–1500 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988 [1964]), Chapter 6.

For a discussion of the medieval Orientalizing of Darius, see Christine Chism, “Too Close for Comfort: Disorienting Chivalry in the Wars of Alexander,” in Sylvia Tomasch and Sealy Gilles, eds., Text and Territory: Geographical Imagination in the European Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 116–142.

Jennifer R. Goodman, Chivalry and Exploration: 1298–1630 (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1998).

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2014 Robert T. Tally Jr.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rouse, R.A. (2014). What Lies Between?: Thinking Through Medieval Narrative Spatiality. In: Tally, R.T. (eds) Literary Cartographies. Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137449375_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137449375_2

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-68752-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-44937-5

eBook Packages: Palgrave Media & Culture CollectionLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)