Abstract

Assessment has traditionally been seen as a way of finding out what students have learned. There has been a relatively recent shift to embedding assessment as an integral aspect of the learning culture of Net Generation learners. In such a shift, pedagogical encounters are characterised by learners engaging with and connecting to other key agentive elements in ways that combine to create a personalised learning network that extends outwards from each student. In this chapter, we focus on four case studies that enhance learning by viewing assessment as part of the ongoing activity emerging from such pedagogical encounters. Each case study acknowledges that an essential part of working with the Net Generation of learners is having a greater sensitivity to how they make sense of learning activities and enacting forms of assessment that are more student centred, reflective and proactive in enabling students to self-manage their learning activity. This has required numerous changes in our roles as teachers, changes in the role of students, changes in the nature of student–teacher interaction and changes in the relationship between the teacher, the student and the course content. One important insight is that if teachers are to be leading learning in their classrooms, it behoves them to become Net Generation learners themselves. We conclude by suggesting that assessment must be deeply embedded as a part of student learning culture and be evoked in ways that work for the Net Generation of learners.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This chapter examines the role assessment can play in motivating and guiding learning for the Net Generation. It has been recognised for some time that assessment is a problematic term that is often used to denote several things at once (Ramsden 2003) . For example, assessment can refer to the process of grading and the process of enhancing learning; it can involve appreciating the issues students encounter and teaching them better; it can be about meeting standards and having explicit criteria of expectations and it can simultaneously generate information and influence future decisions (Carless 2007) . Roos and Hamilton (2005) suggest that such differing purposes reflect deeper discussions about the nature of teaching and learning. They posit that those who lean more towards summative assessment draw from behaviourist learning theories that are focussed on measuring learning, while those who concentrate on formative assessment draw more from constructivist theories of learning and are more focussed on issues of feedback and development. In a similar way, Joughin (2009) proposes that assessment is typically framed in binary terms between a model built around measurement, where knowledge is objective and value free and assessment becomes a means to determine the extent of learning, and a model built around judgement, where knowledge is seen as provisional, subjective and context dependent, and assessment is construed in terms of evaluation, quality and judgement.

Assessment has also been closely aligned to efforts to improve school effectiveness. Within the concerted effort to reconfigure schools for modern times, Mutch (2012) suggests that there are three different movements in assessment that can be identified. The first relates to how assessment is used for accountability purposes to ensure schools are meeting stakeholder needs. The second concerns the role assessment plays in improving student learning, particularly as it relates to the improvement of school processes to achieve societal goals. The third relates to embedding assessment as a sustainable educational practice in terms of enabling students to be lifelong, self-reflective, independent learners and critical thinkers. These discursive movements are captured in the distinction between assessment of learning, assessment for learning and assessment as learning, respectively. In her analysis of assessment in the New Zealand Curriculum, Mutch (2012) suggests that all these purposes operate simultaneously, although their relative importance varies in some policies and at some times rather than others.

Our concern with viewing assessment in this manner is that it can overlook how connected the modern learner has become and the implications this has for the types of learning that emerge. One of the key values of drawing on the concept of the Net Generation is its ability to shift attention to the connecting, connectable and connected nature of modern life and the possible implications this has for recognising the dynamic way an individual’s aspirations, knowledge and identities emerge from the networks they are part of. Connections are relational, meaning that they enable a means of exchange (such as the flow of ideas, information or material goods) and such information can be used as feedback to influence a system’s behaviour (Mützel 2009; Ovens and Godber 2012) . Such a relational orientation focuses attention on the individual learner as part of social networks that extend beyond the school boundaries and afford access to different flows of information. When the form, nature and content of human connections are so numerous and dynamic, what may appear to be a linear and isolated process (i.e. individual students learning in the apparent confines of the classroom) can, on closer inspection, reveal itself to be far more complex (i.e. each student forming a highly personalised learning network across multiple sites).

For the purposes of this chapter, we suggest that assessment is best understood as a set of processes involving technological and social resources that enable those involved (both teachers and students) to engage purposively with evidence of learning in order to enhance the learning process (Daly et al. 2010) . In this way, assessment becomes linked with fostering a learning culture aimed at supporting meaningful engagement with learning activities, inferring from this what learning is emerging, deciding what further resources and connections are needed and providing accountability to ensure learning takes place. Such a definition does not assume the purpose(s) of assessment, who assesses, when assessment occurs or how it is done (Joughin 2009) . It does, however, view assessment as embedded within broader frameworks of learning, which are based on the roles of the participants (teachers, individual learners, peers) and a range of practical and discursive actions in which they participate. It provides a basis for considering these matters clearly and aids the discussion of the relationship between assessment and learning as well as how to skilfully utilise those ‘teachable moments’ that emerge in pedagogical encounters.

2 The Net Generation and Assessment

The concept of the ‘Net Generation’ can be defined in a variety of different ways (as evidenced in other chapters of this book) . Typical definitions point to the nature of the learner and suggest that such learners are somehow substantially different from earlier generations because they have grown up with digital media and are assumed to be universally savvy with information and communication technologies (Hargittai 2010) . Our interest in this chapter is not so much on the debate of whether there is indeed a new generation of learners, but on considering whether this concept better describes the effects of social networks and connectivity on learners. A variety of characteristics have been observed in those described as the Net Generation and these include: familiarity with and regular use of computers; active social networks and highly connected via the World Wide Web; technologically savvy and confident in multimedia environments; a preference to be actively engaged in tasks; and regarding social interaction as important (Hargittai 2010) . However, the empirical evidence suggests that these characteristics tend to be distributed unevenly across the cohort of young people. Based on this, our suggestion is that rather than being a homogeneous generation of learners who are technologically savvy, the concept of the Net Generation is more aptly described as an expression of a possible learning culture enabled by technology.

The nature of this culture and its relationship to changing ideas around learning and how this is enabled by information technology are illustrated in Table 14.1 .

Framing the Net Generation learner in this way recognises that learning cultures are always dynamic, uncertain and that the connection between learner and teacher is ‘not linked by chains of causality, but (by) layers of meaning, recursive dynamics, non-linear effects and chance’ (Osberg 2008, p. viii) . Elliott (2008) suggests four ideas in particular are of particular relevance to understanding this contemporary culture. First, modern information systems provide an ‘architecture of participation’ that not only makes it easy to connect and access information but also improves as more people become involved. Related to this is the second idea of ‘user-generated content’ that refers to the ease of creating and sharing content through social networking sites. Third, the idea of ‘openness’ refers to the philosophy that this content is freely shared among users of the net. The fourth idea relates to the ‘power of the crowd’ and the way being connected can provide access to a diverse range of resources and expertise that constitutes forms of both individual and collective intelligence when needed. The irony is that formal education and schooling risks being disconnected from the social and digital spaces are enabled through technology and social networks.

Such ideas have implications for modernising assessment (Elliott 2008). They seek to bring a future-oriented approach to teaching and learning, not by upgrading to, or foregrounding, a concept of ‘e-assessment’ (through machine marking or other adaptations of modern technology) but by using the same tools and techniques that students use at home and teachers use in their workplace. Elliott (2008) suggests that the type of assessment activity best suited to the emerging educational and technological landscape assessment activities should exhibit some or all of the characteristics in Table 14.2, although the list is not an exhaustive one.

We have used the frameworks as outlined above to consider our assessment practices with Net Generation learners. This assessment does not discriminate between summative and formative assessments, nor does it focus on the ideas of assessment of, for and as learning. Yet, these various distinctions are implicit when we think about working with Net Generation learners. We view such ideas as fluid and dynamic, each coming to the fore if and when required. Unfortunately, we note that there is currently a paucity of examples in the literature of how such principles become enacted in teaching contexts. For that reason, we focus the remainder of this chapter on four case studies in an effort to illustrate how we have enhanced our teaching by drawing on this framework. The case studies cover a range of courses of study, students and technological tools.

3 Case Study One: Negotiated Coursework and Grading Contracts

The first case study addresses the notion that in any typical course, the teacher makes nearly all of the decisions related to what is going to be taught and how it will be assessed. To interrupt this pattern, and encourage students to think more deeply about the value of what they were learning, a cohort (n = 40) of third year students enrolled in the Bachelor of Physical Education (Secondary) Teacher Education Programme were invited to participate in planning and designing a course they would be doing in the following semester. As co-contributors to course design, a representative group of students were invited to negotiate what learning was important to their needs, where and how such learning should occur and how the outcomes should be assessed.

In the initial workshops, there was a lot of discussion around students’ prior experiences of assessment. Concerns were expressed by the students about the ability of traditional forms of assessment to fairly assess their learning. There was also a concern that written assignments (e.g. essays and reports) tend to be the assessment norm and that they were keen to explore alternative ways of demonstrating their learning (e.g. PowerPoint presentations, models, dance or role-play performance). In the end, the workshop group agreed that portfolios seemed to be the logical way to explore many of the ideas discussed and allow individuals to focus their learning around their individual needs. While a number of ideas and approaches were included into the course design, it was agreed that the course use individualised negotiated grading contracts (Brubaker 2009, 2012) .

Negotiated grading contracts allowed students to be involved in many of the key decisions that related to how their learning would evolve and be assessed. In negotiating a grading contract, students were being asked to engage in a meaningful way with assessment decisions they were never normally privy to in other courses. For example, students were asked to explain what they would do to earn a grade for the course, to what extent they would do it, how they would document and present their work, what criteria should be used to judge the quality of the work, and how such judgements would translate to a final grade. Guidelines were provided to assist students with each of these decisions along with active discussions during initial classes. Each contract was also negotiated with the course lecturer and eventually signed when both parties agreed that the contract provided a fair basis for engaging in the course. The process challenged students to think about the nature of the coursework they were undertaking and how it related to both the course goals and their individual aspirations.

Now in its third year, this case study demonstrates the advantage of providing opportunities for assessment to accommodate the characteristics discussed above (see Table 14.1). When learning opportunities are personally tailored, students are in a position to connect their learning with other aspects of their lives and personal aspirations that their lecturers are not normally aware of For example, they may have identified that they need to deepen their understanding of a particular concept they are unsure about, or connect their work across several courses. When students are engaged in learning tasks that are meaningful, authentic and determined by them to be of real use, students often go far beyond what might ordinarily be expected. These students report that they are completing tasks for their own benefit rather than their exchange value for grades as such. Typical of their comments in the end of course evaluation were statement such as ‘I don’t care about the grade. I have learnt so much doing this assignment’.

4 Case Study Two: Engaging Students Through Online Tools

The second case study was with a cohort of students (n = 160) enrolled in the Graduate Diploma (Primary) Teaching Specialisation. In this case, we highlight synchronous and asynchronous learning in their science education course through the use of online learning tools such as PeerWise and Piazza. PeerWise (Denny et al. 2008) was used to engage students in a collaborative learning community in which they created, shared, evaluated, answered and discussed their growing repository of media rich multi-choice questions. Students were asked to upload a science animation or interactive, which could be used in a classroom with children, and to provide one multiple-choice question related to this artefact but directed to their peers as teachers. Students were also required to answer at least five of the questions uploaded by their peers—for a relatively small number of final marks.

Data collected through the PeerWise analytics and from the students’ course evaluations shows this assessment task met many of the assessment criteria in Table 14.2. The task was authentic in that the students spent considerable time sourcing and selecting animations and interactive sites which would be appropriate and valuable resources for their own later use as teachers. By sharing their questions and sites with their peers, they developed a rich and growing repository of resources. The task was personalised in that each student approached it with their own knowledge, skills and interests. The task involved peer review of each other’s postings, and self-reflection based on the feedback the students received from their peers. Because PeerWise is based on some of the familiar gamification aspects of the Net Generation with a leader board and badges for incentivising tasks, technology has made this an even more engaging activity. This was evidenced by participation rates in PeerWise which far exceeded our expectations. Over 86% of students answered more than the five questions required for the maximum marks available for this assessment task; 17 students answered more than 25 questions, with one student answering 104.

These students also used Piazza, synchronously during each session and asynchronously in their own time, throughout the semester. This is an online web application and computing platform combining personal communication, instant messaging, wiki, and social networking and is able to work in real time. Piazza became a back channel during sessions, where students were asked to upload posts commenting on different aspects of conceptual understanding in an ongoing manner throughout each session. This allowed the lecturers to more openly assess student understanding during the session, in real time—and to provide feedback to the class and adjust course content as appropriate. The students were encouraged to provide feedback on each other’s comments, thereby significantly increasing the opportunity for feedback well beyond that which an individual lecturer could provide in any session.

Piazza met the socio-cognitive considerations of collaboration, learning how to learn and the improvement of ideas that is considered essential for knowledge building (van Aalst 2009) . Piazza foregrounds the goal of collective knowledge advancement within a community (Scardamalia and Bereiter 2003) rather than competitive individual gains. The collaboration required more than the students sharing ideas. They had access to the ideas of other students and were able to consolidate these in order to improve their own understanding while at the same time building the knowledge of their peers (van Aalst 2006) . Piazza allows for students to revisit the session, re-read the record and to upload new artefacts for their peers to consider.

Relating to Elliott’s (2008) four ideas of Web 2.0 assessment, both these online tools provided an architecture for participation and relied upon user-generated content, openness and the power of the crowd.

5 Case Study Three: Interactive Teaching

The third case study was with a cohort (n = 40) of first year students enrolled in the Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood Education) Teaching Specialisation. This course was designed to develop students’ understanding of science content and pedagogical content knowledge appropriate for young children in early childhood centres. We believed that a teacher’s science content knowledge is an important determinant of their willingness to engage young children in science activities (Garbett, 2007). We utilised GoSoapBox and e-portfolios to maintain a focus on content knowledge while also encouraging students to curate a pedagogically appropriate and rich resource.

GoSoapBox was used to provide user-friendly short multiple-choice question tests, as formative assessment so that students could see at the beginning, during or at the end of a session how much they knew about a particular topic. Since the tests remained on-line and were supported by other resources, students could continue to develop their understanding after the sessions. We used a random selection of 20 out of the 160 amassed multiple-choice questions in the examination at the end of the course. The average score in the examination was 18.45 out of 20 (92.25 %) with 15/40 scoring 100 % and every student scoring more than 70 %. Even though this was only worth 10 marks in their final grade, we signalled that content knowledge was important if they were going to be confident and competent to facilitate learning about science in the early childhood centre. During the course, students were able to revisit the tests as often as they chose, thus aiding the teacher in relinquishing the role of sole engineer of the learning process and turning epistemic agency over to the students (Scardamalia 2002) . In considering characteristics of Web 2.0 assessment (Elliott 2008), this task was personalised, recognised existing skills, was self-assessed and was tool supported.

Another assessment strategy was the students’ creation of e-portfolios over the duration of the course to record their developing pedagogical content knowledge. Each fortnight, they were required to upload the following: an artefact (e.g. a photo or video clip) of themselves engaged in ‘doing’ science in the workshops; a brief description of their learning for at least two practical science activities; a half-page reflection or description focussed on something that had surprised, excited or puzzled them about teaching that topic to young children; and an original resource or a web-based resource for young children based on the topic. These were marked online, but privately, within five days. Additionally, a general statement which highlighted any common misconceptions, offered alternative explanations and suggested ways to improve the quality of the exchanges was published on the Learning Management System platform. In this way, students were made aware of their progress as a cohort as well as receiving personalised feedback. Of particular note, students commented positively on their control over what they uploaded and took advantage of being able to update work that they had previously submitted into their e-portfolio for grading, based on their new learning.

This epitomises the characteristics of assessment as being personalised and involving self-reflection. Utilising the ‘power of the crowd’ in order to create their e-portfolios gave students access to alternative learning networks beyond their class community, and the capacity to curate numerous sites and expertise accessible in the wider Web.

6 Case Study Four: Peer Marking Panels

The fourth case study was with a cohort (n = 15) of science students enrolled in the Graduate Diploma (Secondary) Teaching Specialisation. As part of their coursework, each student completed an individual research report that was submitted to a marking panel of their peers from the course. There were three panels established within the cohort, with each panel responsible for reviewing and marking a set of research reports from their peers. The panels were organised so no panel member’s report was marked by their panel.

Peer marking panels provided multiple authentic learning opportunities. The process developed a lived understanding of the mechanics of assessment, including peer moderation and standards-based assessment. Having four or five peers comment on each student’s work increased the amount of feedback that each student received. Peer marking panels extended who read and judged the quality of each student’s work. Furthermore, it challenged members of each panel to think about issues related to fairness, standards, criteria and moderation. The course lecturer had the ultimate responsibility for moderating between the panels as well as being the arbiter of any discussion.

One benefit noted by a number of students as members of the marking panels was the value they got from reading the work of their peers. However, a drawback which they drew our attention to via focus group interviews conducted at the end of the course was that some students had been reluctant to have their peers read their work. Transferring this onus from the traditional authority (i.e. the teacher) had undermined their confidence in the social context to an extent that we had not been aware of.

One of the corollaries of the assessment task was that students created media-rich resources with an informative splash page to advertise the web-based resources they had amassed. Collaborating and making their end-point resources available to their peers would have been useful for all of the students. However, because their resources were graded and figured on their official transcripts, the overriding motivation was to maximise the exchange value of them for grades. The ramifications of this were that rather than openly sharing their work, a competitive job market led to most students guarding their final resources closely. This case draws attention to the gap between the theory and practice of implementing Web 2.0 assessment practices for the Net Generation learners.

7 Concluding Thoughts

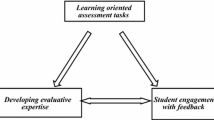

Each of the case studies discussed above offers a different way of invoking assessment as an integral aspect of the learning culture of Net Generation learners. We outlined at the start that in this new culture, pedagogical encounters are characterised by learners engaging with and connecting to other key agentive elements in ways that combine to create a personalised learning network that extends outwards from each student (Ovens and Godber 2012). Such a view places the student at the centre of the learning nexus and positions the teacher as possibly being with, against and alongside other significant elements that also contribute to and shape the individual’s learning. In this sense, it is difficult to define assessment in concrete ways since its form is fluid and emerges as forms of dialogue as students engage with learning activity.

Our focus in the case studies was to enhance learning by viewing assessment as part of the ongoing dialogue emerging from pedagogical encounters. This has required numerous changes in our roles as teachers, changes in the role of students, changes in the nature of student–teacher interaction and changes in the relationship among the teacher, the student, and the course content. Assessment that is more student centred, reflective and proactive in enhancing students’ achievements and their capacity to harness the potential of the net acknowledges that an essential part of working with the Net Generation of learners is having a greater sensitivity to how they make sense of learning activities and the need to adapt pedagogy accordingly. Assessment must be deeply embedded as part of the learning culture and how our students learn. It must be evoked in different ways that work for the Net Generation learners - and if teachers are to be leading learning in their classrooms, it behoves them to become Net Generation learners themselves.

References

Brown, M. (2005). Learning spaces. In D. Oblinger, J. Oblinger, & J. J. Lippincott (Eds.), Educating of the Net Generation. Brockport Bookshelf. Book 272. http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf/272.

Brubaker, N. D. (2009). Negotiating authority in an undergraduate teacher education course: A qualitative investigation. Teacher Education Quarterly, 36(4), 99–118.

Brubaker, N. D. (2012). Negotiating authority through jointly constructing the course curriculum. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18, 159–180.

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: Conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1) 57–66. doi:10.1080/14703290601081332.

Daly, C., Pachler, N., Mor, Y., & Mellar, H. (2010) Exploring formative e‐assessment: Using case stories and design patterns. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 619–636. doi:10.1080/02602931003650052

Denny, P., Hamer J., Luxton-Reilly, A., & Purchase, H. (2008). PeerWise: Students sharing their multiple choice questions. In Fourth International Computing Education Research Workshop (ICER 2008), pp. 51–58, Sydney, Australia, Sept 2008.

Elliott, B. (2008). Assessment 2.0: Modernising assessment in the age of Web 2.0. Glasgow: Scottish Qualifications Authority. Retrieved from http://www.scribd.com/doc/461041/Assessment-20. Accessed 22 Oct. 2013.

Garbett, D. (2007). Assignments as a pedagogical tool in learning to teach science: A case study. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 28(4), 381–392

Hargittai, E. (2010). Digital Na(t)ives? Variation in internet skills and uses among members of the ‘‘Net Generation.’’ Sociological Inquiry, 80(1), 90–113. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2009.00317.x.

Joughin, G. (2009) Assessment, learning and judgement in higher education: A critical review. In G. Joughin (Ed.), Assessment, learning and judgement in higher education (pp. 1–15). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020–8905-32.

Mutch, C. (2012). Assessment for, of and as learning: Developing a sustainable assessment culture in New Zealand schools. Policy Futures in Education, 10(4) 374–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2012.10.4.374.

Mützel, S. (2009). Networks as culturally constituted processes. Current Sociology, 57(6), 871–887. doi:10.1177/0011392109342223.

Osberg, D. (2008). The politics in complexity. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 6(1), 3–13.

Ovens, A., & Godber, K. (2012). Affordance networks and the complexity of learning. In A. Ovens, T. Hopper, & J. Butler (Eds.), Complexity in physical education: Reframing curriculum, pedagogy and research (pp. 55–66). London: Routledge.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Roos, B., & Hamilton, D. (2005) Formative assessment: A cybernetic viewpoint. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 12(1), 7–20, doi:10.1080/0969594042000333887.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In B. Jones (Ed.), Liberal education in a knowledge society (pp. 67–98). Chicago: Open Court.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge building. In J. W. Guthrie (Ed.), Encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., pp. 1370–1373). New York: Macmillan.

van Aalst, J. (2006). Rethinking the nature of online work in asynchronous learning networks. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(2), 279–288.

van Aalst, J. (2009). Distinguishing knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge creation discourses. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(3), 259–287.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ovens, A., Garbett, D., Heap, R. (2015). Using Assessment to Enhance Twenty-First Century Learning. In: Koh, C. (eds) Motivation, Leadership and Curriculum design. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-230-2_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-230-2_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-287-229-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-287-230-2

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)