Abstract

This commentary reviews three chapters which describe the experiences of implementing EMI programmes in Vietnamese universities. It is clear from these chapters that, while success is reported in specific cases, the topdown nature of the implementation of EMI policies means that, in most cases, these are being undertaken with insufficient support for the students and staff involved. The commentrary concludes with a checklist of questions that policy makers might consider before implementing EMI policies or programmes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- English medium of instruction

- Top-down policy making

- Challenges in the implementation of EMI programmes

We can draw two main conclusions from reading these informative and well-researched chapters. The first is that, to do EMI well, a great deal of thought, preparation, consultation among the stakeholders and ongoing support for both the teachers and students involved is necessary, as is some form of quality assurance. The second is that, with rare exceptions, universities in Vietnam have attempted to implement EMI courses without the necessary preparation, consultation and support. In this, they are not alone, as many researchers report similar findings from different parts of the world (e.g. Dearden, 2014; Macaro, 2018).

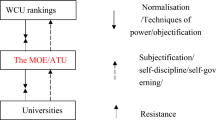

One reason for this lack of preparation, consultation and support in the Vietnamese context may be the top-down way in which the decision to implement EMI courses is made. We must be careful, however, about using the term ‘top-down’ for a Head of Department requiring staff to implement EMI can also be classified as a ‘top-down’ system of management. Here, however, ‘top-down’ refers to the Vietnamese government, primarily in the form of the Ministry of Education and Training, deciding on a policy and requiring universities to implement it. As Min Pham points out, the Vietnamese government has passed a raft of laws aimed at internationalising Vietnamese universities. As has been the case with all moves towards the internationalisation of universities since the adoption of the Bologna Process of 1999 and the establishment of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), universities have adopted EMI programs as the most obvious way to internationalise. EMI programs allow staff and student mobility between universities in different countries, a key part of internationalisation. The initial aim of the Bologna Process and the establishment of the EHEA was to make European universities more competitive and to encourage staff and student mobility, rather than to set up EMI programs as such (Hultgren, 2015). However, it soon became apparent that EMI programs would be needed in order to fulfil the objects of the EHEA, consequently European universities rapidly increased the numbers of EMI programs they offered and these numbers continue to increase (Wachter & Maiworm, 2014). Parallels can be seen with the current Vietnamese experience. As Min Pham makes clear, it is the government’s desire to internationalise the universities that have led to the uptake of EMI programs. These have also been adopted in response to three local pressures, namely national competition, the desire for universities to achieve financial security and local demand for higher education conducted in English. This demand is hard to overestimate. For example, while Vietnam’s first private university was established in 1994, by 2018 there were 95 private universities. Joint training programs with international partners have also increased dramatically, from 133 in 207 to 282 in 2018. These all provide EMI courses. This, in turn, has led to a 20-fold increase in the number of international students in Vietnamese universities, rising from a mere 1100 in 2015 to 21,000 in 2020.

In short, the adoption of EMI programs is inextricably tied to internationalisation. Yet, the major motivations for internationalisation have been political—the perceived need to compete with other universities—and financial—the need for universities to attract funding. By offering EMI programs, universities can charge higher fees for both local and international students. The pedagogical aspects of EMI programs appear not to have been considered. Indeed, it is assumed that students undertaking EMI programs will not only learn the content matter of the subject being taught, but will also develop English language proficiency, as if by osmosis. Lecturers on EMI courses consider themselves subject specialists and do not believe that the teaching of English is their responsibility. Yet a common complaint emanating from EMI lecturers is that many of the students in their courses do not have an adequate level of English proficiency to be able to succeed in their classes. It is also common for students to report dissatisfaction with their lecturers’ level of English. There is therefore a mismatch in expectations between lecturers and students. Lecturers expect the students to have adequate levels of English. Students expect the EMI courses to develop their English proficiency as well as teach the content matter. Given this, it is not surprising that so many EMI courses fail to meet the expectations of staff and students and result in frustrations and anxiety among all stakeholders.

What then, can be done? In their chapter, Nguyen et al. report findings from research conducted at the Danang University of Science and Technology. The university’s Faculty of Advanced Science and Technology teaches (at least) two EMI ‘Advanced Programs’, one in Electronic and Communication Engineering (established in 2006) and the second in Embedded Systems (established in 2008). The Electronic and Communication Engineering program is taught using a curriculum provided by the University of Washington and the Embedded Systems program uses a curriculum imported from Portland State University.

The authors recount the measures the Faculty undertook in order to ensure the successful implementation of these EMI courses. These measures comprised three distinct strategies. First students, in their first year, undertook a 5-month non-credit bearing intensive course in academic English related to engineering. Second, they took credit-bearing courses in the second and third year of the courses. These courses were designed to develop EMI-related soft skills. In their final year, the students complete a capstone project involving English medium study and communication. The third measure is voluntary, as students self-select to engage in project-based EMI activities; this can occur at any stage across the five years of the program and includes engineering projects for community services.

The authors have evaluated these measures and report that they are successful and should therefore be maintained, if not extended. The evaluation of the non-credit bearing intensive academic English courses showed that students could raise their IELTS band scores by 1.5 or 2 bands. 95% of the students scored an IELTS band of lower than 3.5 at the start of the courses, with 65% of students scoring about IELTS band 5 at the end of the intensive course. This seems impressive, although it must be noted that an IELTS band 5 would not be considered adequate to undertake an undergraduate degree in an Australian university, where IELTS band 6 is the usual requirement for direct entry into a program. In a study of EMI in Japanese higher education, students with an IELTS band of 6.5 ‘experienced fewer challenges learning content through English than those below the threshold’ (Rose et al., 2019, p. 10). Importantly, however, the authors also noted that targeted ongoing support in the academic English of the relevant discipline was of benefit to students with lower levels of English proficiency.

The students’ evaluations of the other measures were also positive. In the authors’ own words, students indicated ‘satisfaction with the development of interpersonal, verbal, non-verbal, problem-solving, critical thinking, oral presentation and teamwork skills. In addition, feedback from employers indicates particular appreciation of the quality of student communication skills. Finally, nearly all students participating in project-based extracurricular activities in their fifth year agreed on their improvement in communication skills, including English, self-confidence and motivation, as a result of these projects’.

The above research surveyed students taking an EMI program. The chapter by Thi et al. surveyed 16 Vietnamese EMI lecturers working at a prestigious university and investigated to what extent they were satisfied with their role as EMI lecturers. They found that the positive aspects of the job far outweighed the negative aspects of it. The positive aspects of their job as EMI lecturers were that reading English language materials kept them up to date with developments in their discipline. Reading these English language materials also helped develop their own English language skills. They also reported that, being an EMI lecturer enhanced their personal profile, and that the presence of EMI courses increased the prestige of the university which, in turn, improved the career prospects of their students. Against these positive aspects, they listed a large number of negative ones. These are listed below:

-

Remuneration and workload (pay only slightly higher than teaching VMI courses);

-

Research-related issues. As one lecturer reported, ‘I don’t have time for doing research to enhance English competence and disciplinary expertise due to the heavy workload’. Lecturers also reported they had poor or no access to international journals;

-

The low English competence of some lecturers and the lack of EMI training was given as major cause for dissatisfaction. As one lecturer argued, ‘The institution needs to provide teachers with courses focusing on English support, pedagogical strategies, and best practices to teach disciplinary content knowledge effectively in English’ (see Le et al. for ideas of building English language teaching capacity in Vietnam);

-

The students’ low and disparate English competence was seen as a severe constraining factor hindering the effectiveness of the EMI courses and their own sense of job satisfaction; the general English classes did not meet the needs of students in EMI classes. The low levels of students’ English made interaction difficult. As one teacher reported, ‘I switch to Vietnamese very often to make sure that they catch up with the lesson’.

Given these results, it is not surprising that the authors conclude that, despite having offered EMI programs since 2005, the implementation of EMI programs at the university remains ‘fragmented, ad-hoc, inconsistent and unsustainable’. The authors thus recommend ‘immediate and ongoing professional development projects for EMI teachers to create a transformative impact on EMI practices among academics’. In addition more resources and access to journals and up to date books must be provided. Perhaps above all, students must be adequately prepared.

As noted at the beginning of this commentary, the three chapters in this section of the book make clear how important preparation, consultation and ongoing support for both students and staff is for the successful implementation of EMI programs. They also illustrate how little preparation, consultation and support is actually provided in all but exceptional cases. The major cause of this is the severe disconnect between the government’s understandable desire to internationalise education and the practical needs of the institutions and stakeholders who are required to implement this policy. The top-down nature of decision-making in the Vietnamese context only serves to widen this disconnect as stakeholders are not consulted and thus cannot make their needs known. This is a shame. As the findings from the research reported above show, the needs of the institutions and stakeholders are known and could therefore be acted upon in a systematic way.

Given the top-down nature of the internationalisation policy in Vietnam, I add, in closing, key questions that a colleague and I formulated for national authorities to ponder and answer before moving to implement EMI courses (Kirkpatrick & Knagg, fthc). The questions are:

-

What research has been done in this country and internationally on the prevalence and the success of EMI? What extra research is needed to understand the situation?

-

What benefits might EMI bring to the country? What are the risks of EMI if not implemented well?

-

Is EMI legal? Should there be any restrictions on which institutions can have EMI programs and courses? In which circumstances and to which students?

-

What effect will policies related to HE have on secondary school language use and learning?

-

What effects will EMI have on ability, including professional ability, in national and local languages, with reference to employability in-country.

-

To what extent should HEIs attract international students (who might not speak the national language)?

-

What English teaching provision (which might include EMI) or English proficiency requirement should exist in HEIs?

-

What Quality Assurance mechanisms related to EMI should or must exist in HEIs?

-

What extra resources are available to institutions and teachers to support EMI?

-

To what extent are all these questions decentralised to HEIs?

We also formulated four more general questions which we feel should be discussed at the institutional and departmental level before the implementation of EMI programs. These are:

-

Is one aim of the EMI course to improve English proficiency? If so, how do we know that EMI courses develop the English proficiency of students?

-

Do we know that EMI courses impart content knowledge as least as well as courses taught in the students’ own first language?

-

Will EMI programs add to the division between students from privileged backgrounds and those from poorer disadvantaged backgrounds or will they help those from poorer backgrounds improve their life chances?

-

Will EMI programs undermine the role and status of local languages as languages of education and scholarship? If so, what steps can be taken to ensure that local languages remain as important languages of education and scholarship?

I am aware that answering these questions requires much thought and contemplation. But, if the implementation of EMI programs in the overall drive to internationalise education is to be successful, I feel that these are questions that need to be discussed and debated among all stakeholders.

References

Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction: A growing global phenomenon. The British Council.

Hultgren, A. K. (2015). English as an international language of science and its effect on Nordic terminology: The view of scientists. In A. Linn, N. Bermel, & G. Ferguson, (Eds.), Attitudes towards English in Europe. Language and Social Life (2) (pp 139–164). De Gruyter Mouton.

Kirkpatrick, Andy & Knagg, John (fthc). Language policies and English medium higher education worldwide. In K. Bolton & W. Botha (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of English-medium instruction (EMI) in higher education. Routledge.

Le Van Canh, Nguyen, Hoa Thi Mai, Nguyen Thi Thuy Minh, & Barnard, Roger (Eds.). (2019). Building teacher capacity in English language teaching in Japan. Routledge.

Macaro, E. (2018). English medium instruction. Oxford University Press.

Rose, H., Curle, S., Aizawa, I., & Thompson, G. (2019). What drives success in English medium taught courses? The interplay between language proficiency, academic skills and motivation. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075029.2019.1590690

Wachter, B., & Maiworm, F. (2014). English-taught Programmes in European Higher Education. The State of Play. Lemmens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kirkpatrick, A. (2022). Commentary: EMI in Vietnamese Universities—The Importance of Institutional Preparation, Consultation and Support. In: Pham, M., Barnett, J. (eds) English Medium Instruction Practices in Vietnamese Universities. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 68. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2169-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2169-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-2168-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-2169-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)