Abstract

On the basis that EMI teachers’ job satisfaction is integral to the successful implementation of EMI within universities, we believe that institutions need to consider this aspect more closely when attempting to move forward educationally with their EMI offerings to students. Consequently, this qualitative research investigates factors influencing EMI teachers’ job satisfaction at one Vietnamese university, using (Hagedorn, Hagedorn (ed), New directions for institutional research, Jossey-Bass, 2000) framework of faculty job satisfaction. In-depth interviews with 16 content teachers were conducted with the subsequent utilisation of Nvivo 11 for data analysis. The results showed particular factors functioning as ‘motivators’ in promoting EMI teachers’ job satisfaction, namely achievement, recognition, and advancement. On the other hand, some factors were shown to produce demotivating effects, and could be constructed as what Hagedorn refers to as ‘hygienes’. Hygienes identified were: unsatisfactory payment, inadequate teaching resources, lack of research-related support, students’ English deficiency, lack of professional training and support, and the impossibility of translating beliefs into practices due to the strength of other ‘hygienes’, a new finding. Overall, these research results offer significant implications for fostering EMI teachers’ job satisfaction both at the host university and other institutions of similar context, with the ultimate goal of promoting sustainable development for EMI teachers and EMI university programs in Vietnam.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The goals of EMI programs are associated with improving educational quality, attracting domestic and international students, increasing university ranking on national, regional and international scales, generating institutional revenue, and enhancing the employability of graduates in national and global labour markets (Dang et al., 2013; Duong & Chua, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2016, 2017; Tran & Nguyen, 2018; Trinh & Conner, 2018; Vu & Burns, 2014). However, in practice, the quality and availability of qualified EMI teachers pose enormous challenges for actual implementation (Kirkpatrick, 2011; Nguyen, 2011). According to Le (2012), lecturers have limited English language skills and constrained professional knowledge which leads to decreasing effectiveness of programs. Not only this, but teachers’ classroom practices are influenced by factors such as student performance, institutional support, professional elements, working conditions, academic and curricular issues, all of which exert significant impact on teachers’ job satisfaction (Praver & Oga-Baldwin, 2008; González-Riano & Armesto, 2012 as cited in Fernández-Costales, 2015).

As teachers are key agents in the learning process, they are crucially important in moving forward with EMI in terms of students’ educational outcomes. Consequently, this chapter is an attempt to explore factors influencing EMI teachers’ job satisfaction, with the aim of providing information for appropriate policy development and timely support from institutions to maximise the effectiveness of EMI programs at higher education institutions (HEIs) in Vietnam. Data involving a cohort of 16 EMI teachers were collected through a case study at a single public Vietnamese university.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Workforce Concerns Regarding EMI in Vietnamese Higher Education

For the past two decades, Vietnam’s membership of ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) in 1995, APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation) in 1998, and WTO (World Trade Organisation) in 2006 has resulted in the demand for a high-quality workforce with proficient English and well-educated people (Nguyen et al., 2017; Pham, 2011). The need to promote English language proficiency for human resources is articulated explicitly in the National Foreign Language 2020 Policy (NFL, 2020), and Higher Education Reform Agenda (HERA) (Vietnam Government, 2014). Central to these policies is the implementation of EMI programs at HEIs to foster students’ English competence, generate a well-qualified workforce, and subsequently enhance graduate employability in the international workforce (Le, 2012, 2019). In other words, EMI programs promote students’ global linguistic capital and global cultural capital to achieve their aspiration for career prospects and employability in the labour market of Vietnam’s fast-growing economy (Tran & Nguyen, 2018). The implementation of EMI is therefore a strategic approach for HEIs in Vietnam to keep pace with regional and international developments and ultimately strengthen the nation’s labour workforce in the process of economic and cultural integration (Pham, 2011; Tran et al., 2014).

However, there is a debatable question about the effectiveness of these programs in improving educational quality at Vietnamese universities (Hoang et al., 2018; Le, 2012). Indeed, as Le (2012) points out, in 2008 the Advanced Programs project was considered a failure by the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) after only three years of implementation in 13 top universities across the country. Advanced Programs (Chương trình Tiên Tiến) had been promoted by MOET in partnership with high-ranking overseas HEIs, and recruited high-achieving students with the ultimate goal of placing a Vietnamese HEI among 200 leading universities by 2020 (Marginson et al., 2011). Joint Programs (Chương trình liên kết) partnering with medium-ranking overseas HEIs are also causing concern, as are domestic High Quality Programs (Chương trình Đào tạo Chất lượng cao), which are characterised by cooperation between Vietnamese HEIs and foreign partners with reference to curriculum, materials and assessment of foreign counterparts.

There are several reasons put forward for the issues with EMI implementation. For example, as stated by Nguyen (2018), admissions to Joint and High Quality programs generally do not have entrance exams and the entry requirements are often very low to maximise the intake of enrolments, with the result that students’ English proficiency is frequently inadequate for content learning through EMI. Additionally, quality assurance of such programs is ill-regulated which leads to low academic credentials (Nguyen, 2018). Yet perhaps the most important reasons stem from teacher capabilities, materials, methodology and facilities. Specifically, the main causes hindering the successful implementation of the programs are teachers’ limited English competence and professional knowledge, one-way knowledge transmission from teachers as part of traditional teaching methodology, and inadequate or unsuitable materials (Le, 2012). As such, it can be concluded that teachers play a vital role in boosting the effectiveness of the EMI courses at HEIs in Vietnam. Consequently their levels of job satisfaction are a matter of concern and merit investigation. However, there is a paucity of research for sustaining the effectiveness of EMI implementation on the part of lecturers. Specifically, for over the past 20 years, little attention has been paid to the exploration of job satisfaction among EMI academics which would enable institutions to take necessary and timely measures to generate sustainable conditions for EMI lecturers and thus increase the likelihood of successful educational outcomes of EMI among students.

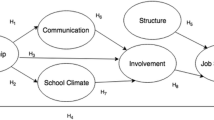

2.2 Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction

It is generally accepted that people with a high level of job satisfaction demonstrate positive attitudes towards their work, while those who are dissatisfied demonstrate negative attitudes. In turn, these attitudes impact on productivity and, in the case of university education, on student outcomes. For this reason, it is vitally important to understand factors that influence job satisfaction. Building on the work of Herzberg et al. (1993), Hagedorn (2000) differentiates two constructs influencing job satisfaction for university academics, namely: mediators and triggers. Mediators refer to the broad context of a working academic life, while triggers refer to events in an individual’s life, such as a promotion or giving birth. As such, triggers are not relevant in this study, whereas mediators, which apply to whole cohorts of teachers, are highly relevant.

For Hagedorn, mediators are factors that can function either positively, as motivators, or negatively, as hygienes. Motivators lead to increased satisfaction; hygienes lead to dissatisfaction. A neutral mediator may act as a preventative hygiene, not exerting any motivating or demotivating effect, but possibly preventing dissatisfaction. Hagedorn (2000) lists the following factors able to function as either motivators or hygienes: achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility, advancement, and salary. A subsequent study by Bentley et al. (2013) found these all to be applicable, and added one more—institutional resources—on the grounds that a lack of physical, human, and financial resources hinders performance, just as other hygienes do. In this study we looked for evidence of all these factors, functioning either as motivators or as hygienes.

Hagedorn (2000, pp. 6–7) refers to two additional types of mediators: demographics and environmental conditions. Demographics relate to individual factors, such as gender, professional ranking, and academic discipline, which we chose not to address in this study given the small sample and our concern with factors applicable to the group rather than to individuals. Environmental conditions relate to whole cohorts of academics, and comprise collegial relationships, student quality or relationships, administration, and institutional climate or culture, which we did choose to address. Based on our experience in the EMI field, we argue that there is another environmental condition that deserves consideration, namely the degree to which teachers are able to translate their pedagogical beliefs into actual classroom practices. On the one hand, ability to translate pedagogical beliefs into practice might be seen in the same way as Hagedorn (2000) sees the ‘stress’ factor, namely as ‘a consequence of negative responses to the mediators’ (p. 9). On the other hand, while stress tends to be associated with nearly all aspects of the job (Hagedorn, 2000), ability to translate pedagogical beliefs into practice is directly related to the teaching process and is not so much a personal response (feeling stressed) as an outcome of environmental conditions affecting pathways for moving forward educationally with EMI. For these reasons, and because of its apparent importance to our colleagues in EMI, we decided to investigate it as an independent mediator related to the teaching environment.

2.3 Beliefs and Their Translation into Practice

Beliefs encompass people’s opinions, conceptions, ideas, or views. They are judgements and evaluations that we make about ourselves, other people, and the world around us (Kunt, 1997; Wang, 1996). In education, beliefs can be defined as teachers’ ideas and viewpoints on teaching and learning (Haney et al., 1996; Khader, 2012). Such beliefs play a pivotal and influencing role in teachers’ classroom practices and their professional development (Gilakjani & Sabouri, 2017). In the context of EMI teaching, research has been conducted to investigate teachers’ beliefs about teaching, and about students, content, and problem-solving strategies for classroom teaching (Kagen, 1990 as cited in Henriksen et al., 2018). Widely held beliefs about the benefits of EMI include intercultural understanding, global perspectives, strengthened economy, greater competitiveness, enhanced employability, and improved educational opportunities for students (Briggs et al., 2018; Hu, 2019).

However, some studies reveal that beliefs may not be reflected in teachers’ practices for reasons of contextual constraint (Akbulut, 2007; Farrell, 2008; Urmston & Pennington, 2008). In other words, contextual factors such as school and classroom environments can constrain teachers in translating their beliefs into practices (Fang, 2006). In EMI, for example, it has been noted that actual practices of EMI are constrained by the English proficiency of both teachers and students (Hu et al., 2014a, 2014b). Specifically, inadequate English capacity leads to students’ challenges in comprehending lessons and materials; teachers’ inability to teach interactively, which is a feature of intended EMI pedagogy; and teachers’ provision of merely superficial instructional content (Hu, 2019; Simbolon, 2016). In order to cope with such challenges, teachers resort to strategies such as: simplifying the content, avoiding interaction and improvisation with students, minimising spontaneous discussions, code-switching from the new language (L2) to the national language (L1), and translating instructional content from L2 to L1 (Hu, 2019). These coping strategies are said to have had negative impacts on the teaching and learning of subject content and the development of English language competence (Hu, 2019). We argue that this environmental condition is a matter of concern in regard to EMI teachers’ job satisfaction in Vietnamese universities and needs to be specifically attended to in research.

3 Research Design

3.1 The Research Questions

With a view to understanding institutional responsibilities in regard to EMI programs, this study investigates the following three questions:

-

1.

What factors influence the job satisfaction of EMI teachers in a Vietnamese university?

-

2.

What factors constrain EMI teachers when translating their pedagogical beliefs into practices?

-

3.

What correlation is there between teachers’ beliefs, achievable practices, and job satisfaction?

3.2 The Research Context

University G is a prestigious HEI in Vietnam which offers business-related courses such as Finance and Banking, Business Administration, Accounting, Marketing, International Trade, and Economics, for undergraduate and postgraduate students. It has established cooperation with 50 HEIs from different countries across the world and officially has Joint Programs with many well-established and renowned universities from Canada, Austria, France, China, and Taiwan. EMI programs at University G are taught by overseas lecturers and university academics who have obtained postgraduate qualifications from various countries, including America, England, Japan, Sweden, Germany, and Taiwan. The students in such programs are both undergraduate and Master of Business Administration (MBA) students. Undergraduate students pursue a High Quality Program with higher tuition fees than the standard program. MBA students pursue English-taught Joint Programs between University G and its counterparts from France, Canada, Taiwan, and Austria.

Having initiated EMI programs in 2005, the university has currently achieved remarkable outcomes in training high quality graduates with high English proficiency and excellent professional knowledge. However, although the programs have shown signs of considerable success, there still exist several issues that need to be tackled. As in many other institutions in Vietnam, the implementation of EMI in University G is still fragmented, ad-hoc, inconsistent, and unsustainable (Tran & Marginson, 2018).

3.3 Data Generation and Analysis

The three researchers conducted individual interviews with 16 content lecturers at University G. Their EMI courses involved Business environment, Start-up, Human resource management, Accounting, Financial management, and Corporate finance. The EMI teaching experience of these teachers ranged from 5 to 15 years. Most of them had obtained postgraduate qualifications overseas, while those lecturers who achieved a postgraduate degree in Vietnam had to meet a required overall score of 6.0 IELTS to teach EMI courses.

Each interview was conducted in Vietnamese and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. All the conversations were audio recorded, transcribed in Vietnamese, and translated into English in preparation for later analysis. With the support of NVivo 11, a thematic data analysis approach enabled researchers to interpret meaning from the content of the interview transcripts through coding and identifying emerging themes (Creswell, 2012). These themes in turn could be closely associated with the key research question regarding factors influencing job satisfaction. Hagedorn’s (2000) conceptual framework of motivators, hygienes, and environmental conditions then enabled deeper data analysis. We see this framework, as Hagedorn (2000, p. 17) does, as ‘an aid to better understand the commonality that faculty share and provide a structure on which institutional analysis of job satisfaction can be based’. For our data analysis purposes in this study (see Table 4.1), we have included the two additional mediators identified in Sect. 2.2, namely: institutional resources—identified in Bentley et al., (2013)—and translation of beliefs into practice—proposed by us as a potential mediator in current Vietnamese university settings and a key focus in this study.

4 Findings: EMI Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

The interview data revealed that there were several factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction—comprising both motivators and hygienes, as well as environmental conditions.

4.1 Motivators

The teachers reported benefitting in several ways from teaching EMI at their university, notably improvement of English competence and the development of professional knowledge. Teacher 10 provided an example of this view:

When teaching EMI, I have to read many materials in English. Those state-of-the-art materials are very up-to-date and stimulating so they help me to improve my English and simultaneously widen my professional knowledge. This gives me a sense of professionalism, self-improvement and advancement.

Noticeably, several teachers reported that lecturing in EMI programs accommodated enhancement of their professional profile. Apart from teaching at their university, they receive many offers to lecture in other prestigious higher education institutions, helping them to expand their professional network and gain increasing recognition. This finding contrasts with the study by Briggs et al. (2018) whose results only reported on challenges to teachers of EMI. Indeed, benefits to EMI teachers are not widely referred to in the EMI literature internationally.

While recognition and advancement of EMI teachers appear to function as direct motivators for job satisfaction, benefits to the institution and to students could be seen as indirect motivators or perhaps as ‘preventative hygienes’. In these teachers’ view, the implementation of EMI at their institution is now a mainstream approach that enhances the prestige of the university in the context of profound globalisation and internationalisation. Teacher 15 commented:

I believe that the university’s implementation of EMI programs definitely helps to increase our ranking because these programs are associated with well-selected curriculum and well-qualified teachers which lead to the enhancement of educational quality. It is a sure-fire way to catch up with the development of HIEs domestically, regionally and internationally.

Many teachers also held the belief that in order to survive in the increasingly competitive higher educational environment, the institution’s adoption of EMI is an inevitable trend to attract more domestic as well as international students. As Teacher 3 said:

Currently, the labour market seeks highly skilled graduates who have both English and professional competence. So, a large number of parents and students in Vietnam desire to have bilingual education. Accordingly, they favour English-taught courses to ensure their success in the future. Moreover, the programs also allow the university to recruit international students and faculty.

These statements endorse the findings of Briggs et al. (2018) and Hu (2019) in regard to EMI as a factor in institutional competitiveness, as well as providing improved educational opportunities for students.

With regard to student benefits from EMI programs, teachers stated that students had the opportunity to access internationalised curricula and global perspectives as against the outdated perspectives in Vietnamese-medium programs. They also benefited from creative, communicative, and collaborative teaching styles from well-qualified teachers. Additionally, graduates from EMI programs have good career prospects because their English proficiency and expertise are expected to exceed those of students who pursue standard programs. Teacher 6 illustrated this point:

Vietnamese family and students are now very practical-minded. More and more students study EMI to look for employment opportunities in the future. They also hold the view that great English skill accompanied with good expertise will ensure a high status in society.

This finding is once again in line with studies by Briggs et al. (2018) and Hu (2019) reporting the positive employment prospects for students pursuing EMI programs.

4.2 Hygienes

Hygienes working against teachers’ job satisfaction were considerably more numerous than motivators, indicating an overall low level of job satisfaction. Hygienes primarily related to the following areas of concern:

-

remuneration and workload

-

research-related issues

-

teachers’ low English competence and lack of EMI training

-

students’ low and disparate English competence

-

teaching-related issues, including teaching and learning resources

While the first two areas of concern relate to teachers’ professional life in general, the last three relate directly to the classroom practice of EMI. It is noteworthy that our data set gave no information about two potential mediators identified by Hagedorn (2000), namely responsibility and collegial relationships. None of the participants mentioned responsibility for managing EMI teaching processes as either a motivator or a hygiene, which may mean that they took for granted the degree of responsibility they experienced. Similarly, none mentioned collegial relationships, neither within their discipline nor with English language specialists with whom they might have been collaborating in some way. This suggests either that such collaboration was not occurring or was not expected. However, we can only be certain of participants’ views on the following factors.

4.2.1 Remuneration and Workload

Concerning the pay rate for EMI classes, almost all the teachers affirmed that the payment was far from satisfactory given the workload. Even though English-taught courses require tremendous effort in preparing classes, according to these teachers the rate per hour for EMI programs is only just slightly higher than for standard programs. As a result, teachers lack motivation for EMI teaching. Teacher 9 said:

Normally, teachers must spend a lot of time reading various materials to prepare for each lesson, but the payment is not satisfactory. If the rate is a lot higher than for the standard programs, I think I will have more motivation and devotion to the course. However, with the current payment and heavy workload at school, I do not invest properly in the lectures.

Low payment is perceived as the main source of dissatisfaction with EMI teaching by most of the lecturers, who consider that policy pertaining to financial incentives should be established and implemented.

4.2.2 Research-Related Issues

Five of the teachers explicitly stated that another factor leading to dissatisfaction was the inadequacy of research-related conditions at institution level, including heavy workload, lack of a private room, and shortage of academic resources. Workload was critical as ‘in order to teach EMI successfully, it is necessary to do research in English to improve English skills and broaden content knowledge at the same time’ (Teacher 16). Teacher 11 further illustrated the disadvantageous conditions for engaging in research:

I don’t have time for doing research to enhance English competence and disciplinary expertise due to the heavy workload. Also, due to a limited personal budget along with the lack of a resources-support policy from the university, we have very rare opportunities to access journal articles and books from world renowned and prestigious publishers such as Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor & Francis, etc. This inhibits our engagement in research. Moreover, teachers at our university do not have our own office so as to work free from the possibility of interruption. We need our own office with adequate facilities to do research.

Teacher 16 considered that ‘the university should take decisive actions to accommodate EMI teachers’ needs to promote their teaching and research activities in order to foster sustainable professional development’.

4.2.3 Teachers’ Low English Competence and Lack of EMI Training

The limited English language skill of teachers along with the lack of EMI training and English language development courses were given as a major cause of many teachers’ low level of satisfaction. There was a disparity in language competence between teachers who pursued their studies in English-speaking countries and teachers who obtained their postgraduate degree in Vietnam and elsewhere in Asia and Europe. The former hardly had any challenges in regard to giving lectures in English, while the latter confessed to struggling to lecture in English due to their limited proficiency. Even those with fluent English still argued that it was necessary for the institution to organise frequent teacher support programs to sustain the ongoing development of EMI methodologies as well as the development of linguistic competence related to teachers’ subject area needs. Teacher 12 said:

The institution needs to provide teachers with courses focusing on English support, pedagogical strategies, and best practices to teach disciplinary content knowledge effectively in English.

This recommendation clearly distinguishes three needs to be addressed: the development of teachers’ English language competence; guidance on pedagogical strategies that reflect the active learning approach of programs imported from overseas; and guidance on achieving the content goals of the discipline through effective EMI practices.

4.2.4 Students’ Low and Disparate English Competence

Teachers believed that students’ low and disparate English competence was a severe constraining factor hindering the effectiveness of the EMI courses and their own sense of job satisfaction. A number of studies indicate that, generally, EMI courses conducted only in English pose a great challenge to Vietnamese students, given that they are non-native English speakers (Le, 2012; Nguyen et al, 2017; Tran & Nguyen, 2018). While a small number of EMI students are excellent in both English and expertise, many others struggle desperately in every lesson. Teacher 9 illustrated this point:

There is a divergence in students’ English proficiency. Some have excellent English due to their favourable conditions for learning intensive English at school, at home and at English centres. However, those who come from less advantaged areas are not proficient enough to follow the programs.

The concern about students’ inadequate English competence confirms previous results such as in Beckett and Li (2012). The task of trying to teach content through English to students lacking sufficient English clearly raises a student quality factor that impacts on teachers’ job satisfaction.

Teachers considered that General English classes did not provide adequately for undergraduates’ needs in their disciplines. They therefore saw needs analysis as a necessity as input for designing suitable and effective student language support programs.

Currently, there is a misalignment between students’ General English classes and the actual English needed for EMI classes. This problem should be addressed by the institution to have proper measures in promoting English skill for accommodating EMI learning. (T12)

Noticeably, the misalignment between students’ General English class and their actual need for English in particular EMI courses acted as hygiene which produced demotivating effects in teachers. The problem can be tackled by the institution’s provision of a language-support program that embraces not only discipline terminology but also academic English and other related soft skills.

4.2.5 Teaching-Related Issues

In fact most teachers complained about how students’ inadequate English proficiency hindered their instructional strategies. For example, due to the poor English proficiency of students and some of the lecturers, there could be little interaction between teacher and students during the lesson, as well as between students and students. While the teachers believed EMI required a creative, communicative, and collaborative teaching style, this was not possible in the circumstances. Also, apart from some highly proficient students, the rest found it hard to comprehend the lectures fully, so teachers used a range of practices in attempting to respond to that situation, taking into account also of their own command of English.

Typically, these proficiency challenges led to frequent code-switching and also to reducing the content of the lecture due to the extra time needed for explaining in both English and Vietnamese. One experienced teacher who held a doctorate from an English-speaking country commented:

Although I know that EMI means “English-only” lessons, when it comes to teaching practices, the reality is different from what I thought earlier. The limited English ability of students prevents them from fully understanding the lecture if I use English most of the time. So I switch to Vietnamese very often to make sure that they catch up with the lesson.

Switching into Vietnamese also occurred in response to teachers’ own insufficient English language proficiency. As one teacher admitted:

I am not very confident about my English so it is very hard for me to lecture continually in English during the lesson. Thus, I use both English and Vietnamese to make it easier for me and I think students also have better understanding when I teach a new concept or new matter in Vietnamese.

These teachers’ comments are in line with Hu’s (2019) findings, where code-switching as a result of limited English level is identified as a common phenomenon for non-native EMI teachers.

Such teachers had slides displaying in English while lecturing in Vietnamese; they avoided interaction with students for fear of revealing their limited English; and were concerned about their inability to give an in-depth, content-rich lesson. As a result, typical features of their EMI classes were: one-way knowledge transmission from teachers; lack of connection between teacher and students; insufficient interaction between students and students in negotiating subject matter; and very few opportunities for student involvement in the construction of knowledge. Thus, teachers’ practices differed from their pedagogical beliefs in three overlapping ways: language use, instructional strategies, and classroom interaction.

As one step towards addressing this gap between beliefs and practices, Teacher 9 recommended that:

Actually, we need training courses for effective EMI teaching which train us how to conduct EMI lessons successfully, how to interact with students and how to encourage student-student collaboration. In fact, our university rarely sends us to those courses, so we don’t have any opportunity to improve EMI pedagogy.

This reference to lack of training courses supporting EMI teachers to translate beliefs into practice is an indication of dissatisfaction, and can be considered an environmental condition related to the institutional climate for EMI teachers.

Another problematic issue affecting the enactment of pedagogical beliefs, and one encountered by a majority of teachers, was access to suitable teaching resources. As mentioned earlier, teachers affirmed that EMI programs offered them the opportunity to read updated content materials. However, in practice, there was no official and systematic provision of up-to-date resources at their university. In addition, because the selected textbooks and curricula were imported or adapted from overseas countries, the content was somewhat unrelated to the current context of Vietnam. Teacher 6 elaborated:

Up-to-date teaching resources enormously facilitate teaching and learning in EMI courses in my field. We have put forward recommendations for the university to purchase newly published textbooks and reference books from prestigious publishers around the world; however, due to financial reasons and some other reasons, we are still not provided with what we require.

It appears that the lack of up-to-date academic discipline-based materials and learning materials suited to EMI and relevant to the Vietnamese context is a hygiene factor relating to institutional resources that hinder the performance of both teachers and students. To sum up, there evidently exist many challenging and constraining factors in regard to translating teachers’ beliefs into practice, which together exert a significant impact on their job satisfaction.

5 EMI Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: Summary

Using Hagedorn’s (2000) approach, the investigation has uncovered a range of mediators relating to EMI teachers’ job satisfaction with EMI jobs. Table 4.2 is presented as a simple summary of the key findings drawn from the interviews with EMI teachers at University G. While Hagedorn (2000) identified responsibility and collegial relationships as mediating factors, our data set gave no information about either of them, and they are consequently excluded from the Table 4.2 summary of findings, even though we recognise their likely validity across this and other EMI settings. On the other hand, we did find evidence of institutional resources (Bentley et al, 2013) being a factor, as well as the degree to which teachers were able to translate their pedagogical beliefs into actual classroom practices, as we had anticipated.

6 Conclusion and Implications for Moving Forward with EMI

As Table 4.2 summary indicates, achievement, recognition, and advancement all function as motivators conducive to increasing job satisfaction among EMI teachers. Most noticeably, by participating in EMI teaching programs, teachers consistently tend to gain improved English competence and enhanced professional knowledge. Further, as teaching another discipline in English is a demanding task for non-native teachers in Vietnam, EMI teachers are highly respected and well-recognised. As mentioned earlier, the invitation to deliver EMI lectures in other institutions has opened up the opportunity to expand their professional network and advance their career. These latter findings are novel in the sense that previous studies rarely document such motivators in EMI.

Acting as hygienes in this study are features of the work itself, as well as inadequate salary and institutional resources, leading to diminished satisfaction among EMI teachers. Specifically, as far as the work itself is concerned, the challenges from the limited English capacity of students and/or lecturers have constrained teachers’ instruction, students’ comprehension, students’ performance, and peer and teacher–student interactions, all of which negatively affect the practice of EMI and consequently teachers’ job satisfaction as well. Further, the lack of available research time was reported as hindering teachers from meticulous preparation for their lectures, as well as expansion of their own content knowledge and improvement of their English skills.

At the same time as pointing out these various hygienes, participants put forward proposals for ameliorating them. For example, they advocated English language-support programs for teachers and students as well as ongoing training in EMI practices for teachers. They called for supportive research policy and resourcing. They also proposed that the institution should increase payment for those who deliver lectures in English-taught programs as this task is demanding in terms of both subject matter knowledge and English competence. The interview data suggests that commensurate payment would enhance their motivation, dedication, and satisfaction. Along with payment, participants also called for access to institutional resources such as updated discipline-based materials, suitable learning materials relevant to the Vietnamese context, and personal office space. These were expected to facilitate moving forward educationally with EMI and thus enhance student experience as well as job satisfaction among teachers.

In regard to environmental conditions, strong predictors associated with job dissatisfaction are: student quality in terms of English proficiency, the absence of an English entry requirement for admission into EMI programs, heavy teaching load yet lack of professional development opportunities, and the impossibility of translating EMI beliefs into related pedagogical teaching practices. This last is a new finding not previously identified as a factor affecting teachers’ satisfaction, and we have added it as a fourth environmental condition. Given that the capacity to translate EMI beliefs into practice is closely associated with several of the other identified mediators, it resembles to some degree the stress factor in Hagedorn’s (2000) finding, in which she perceives stress as an all-inclusive factor that overlaps with nearly all aspects of the job and as ‘a consequence of negative responses to the mediators’ (p. 9). However, we believe the translation of EMI beliefs into practices needs to be marked out as a mediator in its own right because it is so directly related to the educational effectiveness of EMI. Marking it out may also alert institutions to its importance and encourage them to acknowledge and actively respond to it by addressing other mediators within their power.

As mentioned earlier, we share Hagedorn’s (2000, p. 17) view that a framework of mediators provides ‘a structure on which institutional analysis of job satisfaction can be based’. Consequently, drawing on both the literature review and the case study presented here, we propose in Table 4.3 a tool for analysing EMI teachers’ job satisfaction in Vietnamese universities, which we believe may also have application in other countries with similar EMI settings. The tool provides a set of mediating factors that universities need to monitor in order to assess job satisfaction among their EMI staff, and which they can use as guidance for responsive institutional policy and actions that could be taken.

EMI teachers at University G are non-native English speakers and encounter the same challenges as non-native teachers elsewhere across the globe to implement effective EMI teaching, including limited linguistic and pedagogical competence (Dearden & Macaro, 2016). Therefore, it has been critical to investigate the factors influencing their job satisfaction, with a view to sustaining them in such a way that EMI programs simultaneously become more successful in terms of student outcomes. The study revealed that some mediators—such as achievement, recognition, and advancement—promoted job satisfaction, whereas a larger number of other mediators were demotivating factors—unsatisfactory payment, inadequate teaching resources, lack of research-related support, students’ English deficiency, lack of professional training and support, and the impossibility of translating beliefs into practices. Together, these demotivating factors wield considerable influence on teachers’ job satisfaction. At the same time, some of them are the very same factors that typically constrain the educational effectiveness of EMI programs internationally.

Accordingly, universities should make every effort to accommodate teachers in teaching-related support, research-related support, adequate remunerations, and through student-centred provisions that will facilitate the translation of pedagogical beliefs into viable practices. We recommend immediate and ongoing professional development projects for EMI teachers to create a transformative impact on EMI practices among academics, thereby enhancing the educational effectiveness of EMI programs. This requires effort from EMI teachers and strategic support from the institution. Supportive policies in relation to professional development courses could possibly help to prevent job dissatisfaction and gradually foster a high level of satisfaction. As such, the satisfaction and sustainability of EMI implementation could be achieved with the enhanced professionalism of teachers. Professional activities such as language-support programs, study tours in English-speaking countries, scholar exchanges, travel grants for international conferences (Ball & Lindsay, 2012), discussion forums, and collaborative action research to deal with pedagogical issues in the EMI classroom (Burns, 2010) are among possible effective measures to improve the capability of EMI teachers, which in turn may increase teachers’ sense of job satisfaction. In addition, facilities to support research, and financial incentives are among the important considerations for universities to enhance teacher satisfaction and sustain ongoing development. However, to fully enable the translation of teachers’ pedagogical beliefs into viable practices, universities must also enact student-centred provisions that will adequately prepare them for EMI and support them through their EMI disciplinary learning. This includes sufficiently high entry levels of English proficiency, effective preliminary and ongoing language-support courses, as well as available and updated EMI course books and materials. We believe all these proposed measures would serve as important motivation to boost teachers’ dedication to EMI programs and to allow them to move forward with their EMI pedagogies.

References

Akbulut, Y. (2007). Exploration of the beliefs of novice language teachers at the first year of their teaching endeavours. Selcuk University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, 17(1), 1–14.

Ball, P., & Lindsay, D. (2012). Language demands and support for English medium instruction in tertiary education: Learning from a specific context. In A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster, & J. M. Sierra (Eds.), English medium instruction at universities: Global challenges (pp. 44–64). Multilingual Matters.

Beckett, G. H., & Li, F. (2012). Content-based English education in China: Students’ experiences and perspectives. The Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education., 7(1), 47–63.

Bentley, P. J., Coates, H., Dobson, I. R., Goedegebuure, L., & Meek, V. L. (2013). Factors associated with job satisfaction amongst Australian university academics and future workforce implications. In P. J. Bentley, H. Coates, & I. R. Dobson (Eds.), Job satisfaction around the academic world (pp. 29–53). Springer Science+Business Media.

Briggs, J. G., Dearden, J., & Macaro, E. (2018). English medium instruction: Comparing teacher beliefs in secondary tertiary education. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(3), 673–696. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.3.7

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Pearson Education.

Dang, T. K. A., Nguyen, H. T. M., & Le, T. T. T. (2013). The impacts of globalisation on EFL teacher education through English as a medium of instruction: An example from Vietnam. Current Issues in Language Planning, 14(1), 52–72.

Dearden, J., & Macaro, E. (2016). Higher education teachers’ attitudes towards English medium instruction: A three-country comparison. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 6(3), 455–486.

Duong, V. A., & Chua, C. S. K. (2016). English as a symbol of internationalisation in higher education: A case study of Vietnam. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(4), 669–683.

Fang, Z. (2006). A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educational Research, 38(1), 47–65.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2008). Learning to teach language in the first year: A Singapore case study. In T. S. Farrell (Ed.), Novice language teachers: Insights and perspectives for the first year (pp. 43–56). Equinox Publishing.

Fernadez-Costales, A., & Gonzalez-Riano, A. A. (2015). Teacher satisfaction concerning the implementation of bilingual programmes in a Spanish University. Porta Linguarum, 23, 93–108.

Gilakjani, A. P., & Sabouri, N. B. (2017). Teachers’ beliefs in English language teaching and learning: A review of the literature. English Language Teaching., 10(4), 78–86.

Hagedorn, L. S. (2000). Conceptualising faculty job satisfaction: Components, theories, and out-come. In L. S. Hagedorn (Ed.), New directions for institutional research (pp. 5–20). Jossey-Bass.

Haney, J., Czerniak, C., & Lumpe, A. (1996). Teacher beliefs and intentions regarding the implementation of science education reform strands. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33(9), 971–993.

Henriksen, B., Holmen, A., & Kling, J. (2018). English medium instruction in higher education in non-Anglophone contexts. In B. Henriksen, A. Holmen, & J. Kling (Eds.), English medium instruction in multilingual and multicultural universities. Routledge.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (1993). The motivation to work. Transaction.

Hoang, L., Ly, T. T., Pham, H. H. (2018). Vietnamese Government policies and practices in internationalisation of higher education. In L. T. Tran, & S. Marginson (Eds.) Internationalisation in Vietnamese higher education, Springer International.

Hu, G. (2019). English-Medium instruction in higher education: Lessons from China. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(1), 1–11.

Hu, G., Li, L., & Lei, J. (2014a). English-medium instruction at a Chinese University: Rhetoric and reality. Language Policy, 13(1), 21–40.

Hu, G., Li, L., & Lei, J. (2014b). English medium instruction at a Chinese university: Rhetoric and reality. Language Policy, 13, 21–40.

Hüppauf, B. (2004). Globalisation – Threats and Opportunities. In A. Gardt & B. Hüppauf (Eds.), Globalisation and the Future of German (pp. 3–24). Mouton de Gruyter.

Johnson, K. E. (1992). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for non-native speakers of English. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(1), 83–108.

Khader, F. R. (2012). Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs and Actual Classroom Practices in Social Studies Instruction. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(1), 73–92.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2011). English as a medium of instruction in Asian education (from primary to tertiary): Implications for local languages and local scholarship. Applied Linguistics Review, 11, 99–119.

Kunt, N. (1997). Anxiety and beliefs about language learning: A study of Turkish speaking university students learning English in North Cyprus. Dissertation Abstracts International, 59(01), 111A. (UMI No. 9822635).

Le, D. M. (2012). English as a medium of instruction at tertiary education system in Vietnam. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 9(2), 97–122.

Le, T. T. N. (2019). University lecturers’ perceived challenges in EMI: Implications for teacher professional development. In V. C. Le, H. T. M. Nguyen, T. T. M. Nguyen, R. Barnard, Building teacher capacity in English language teaching in Vietnam. Routledge.

Marginson, S., Kaur, S., & Sawir, E. (2011). Regional dynamism and inequality. In S. Marginson, S. Kaur, & E. Sawir (Eds.), Higher Education in the Asia-Pacific (pp. 433–461). Springer.

Nguyen, H. T. M. (2011). Primary English language education policy in Vietnam: Insights from implementation. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(2), 225–249.

Nguyen, H. T., Hamid, M. O., & Moni, K. (2016). English-medium instruction and self-governance in higher education: The journey of a Vietnamese university through the institutional autonomy regime. Higher Education, 72(5), 669–683.

Nguyen, H. T., Walkinshaw, I., & Pham, H. H. (2017). EMI programs in a Vietnamese university: Language, pedagogy and policy issues. In B. Fenton-Smith, P. Humphreys, & I. Walkinshaw (Eds.), English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific (pp. 37–52). Springer.

Nguyen, N. (2018). Transnational education in the Vietnamese market: Paradoxes and possibilities. In L. T. Tran, & S. Marginson (Eds.), Internationalisation in Vietnamese Higher Education, Higher Education Dynamics 51. Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and education research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Education Research, 62, 307–332.

Pham, H. (2011). Vietnam: Struggling to attract international students. University World News, (202). http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=2011121617161637

Praver, M., & Oga-Baldwin, W. (2008). What motivates language teachers: Investigating work satisfaction and second language pedagogy. Polyglossia, 14, 137–150.

Simbolon, N. E. (2016). Lecturers’ perspectives on English medium instruction (EMI) practice in Indonesian higher education [Doctoral Dissertation]. Curtin University.

Tran, L. T., & Nguyen, H. T. (2018). Internationalisation of higher education in Vietnam through English medium instruction (EMI): Practices, tensions, and implications for local language policies. In I. Liyanage (Ed.), Multilingual education yearbook 2018: Internationalisation, stakeholders & multilingual education contexts. Springer.

Trần, L. T., Marginson, S., Đỗ, H. M., Đỗ, Q. T. N., Lê, T. T. T., Nguyễn, N. T., Vũ, T. T. P., Phạm, T. N., Nguyễn, H. T. L., & Hồ, T. T. H. (Eds.). (2014). Higher education in Vietnam: Flexibility, mobility and practicality in the global knowledge economy. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Tran, T. L., & Marginson, S. (2018). Internationalisation of Vietnamese higher education: An overview. In L. T. Tran, & S. Marginson (Eds.), Internationalisation in Vietnamese higher education. Springer International.

Trinh, A. N., & Conner, L. (2018). Student engagement in internationalisation of the curriculum: Vietnamese domestic students’ perspectives. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(1), 154–170.

Urmston, A., & Pennington, M. C. (2008). The beliefs and practices of novice teachers in Hong Kong: Change and resistance to change in an Asian teaching context. In T. S. Farrell (Ed.), Novice language teachers: Insights and perspectives for the first year (pp. 43–56). Equinox.

Vietnam Government. (2014). Fundamental and comprehensive reform of higher education 2006–2020. www.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/chinhphu/hethongvanban?class_id=2&_page=1&mode=detail&document_id=192343

Vu, N. T. T., & Burns, A. (2014). English as a medium of instruction: Challenges for Vietnamese tertiary lecturers. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 11(3), 1–31.

Wang, S. (1996). A study of Chinese English majors’ beliefs about language learning and their learning strategies. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57(12), 5021A. (UMI No. 9716564).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pham, T.T.L., Nguyen, K.N., Hoang, T.B. (2022). Mediating Job Satisfaction Among English Medium Instruction Teachers in Vietnamese Universities. In: Pham, M., Barnett, J. (eds) English Medium Instruction Practices in Vietnamese Universities. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 68. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2169-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2169-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-2168-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-2169-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)