Abstract

This chapter draws on the preceding chapters in Part 2 of this volume to consider the Graduate Teacher Performance Assessment (GTPA) task and its implementation from the perspective of cultural-historical activity theory. Concepts of re-mediation and motive object of activity are used to explain how the GTPA and the work of the GTPA Collective have changed practices of teacher education in Australia and fostered the agency of participating teacher educators. Blunden’s concept of collaborative projects as the appropriate unit of analysis for understanding the development of human practices is employed to show how the GTPA has re-mediated initial teacher education practice across a range of scales. The chapter concludes with a call to build further on recent developments that reveal the potential of the GTPA for preservice teachers to experience the assessment as a collaborative project.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since 2015, Australian providers of initial teacher education (ITE) have been required to include a teaching performance assessment (TPA) in the final year of preservice teacher education programs (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2015; revised 2018, 2019). These TPAs are envisaged in teacher education policy as having two purposes: first, to ensure graduates of ITE demonstrate the Graduate level of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST; AITSL, 2011, revised 2018) and are therefore ‘classroom ready’ (Craven et al., 2014); and second, to provide an evidentiary basis upon which teacher education programs can evaluate and re-design their curriculum offerings to educate preservice teachers to meet the Graduate standards. While such an initiative appears both desirable and straightforward, as the chapters in this volume show implementation of a TPA is a complex undertaking, requiring co-ordinated psychological and practical activity across a range of stakeholders whose interests are not necessarily aligned.

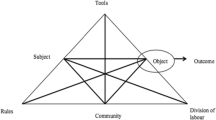

This chapter aims to make sense of this complexity through the conceptual framework of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT; Engeström, 2014). The chapter responds to a question that has intrigued me throughout the development of the Graduate Teacher Performance Assessment (GTPA®)Footnote 1: What exactly does the GTPA do that is not already being done in initial teacher education? In the context of this volume, I have re-cast this question as: How might we understand the nature of the GTPA, as evidenced by the accounts of its implementation by teacher educators in this book? In other words, my empirical method is to treat the preceding chapters (Chaps. 5–8, in particular) as data upon which to build a (partial and necessarily tentative) focal theory about the nature and impact of the GTPA for ITE in Australia. The outcome of this approach is an argument for the GTPA as a multi-scalar collaborative project (Blunden, 2014), characterised by an authoritative reclamation of the agency of Australian teacher educators.

I begin by locating myself within conversations about the development of the GTPA at the Australian Catholic University (ACU) and the work of the GTPA Collective, led by researchers in the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education (ILSTE). I then turn to the conceptual framework I bring to addressing my research question. While there are a number of frameworks that might lend themselves to an analysis of the chapters (Critical Discourse Analysis being an obvious candidate), the conceptual framework I use here is cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT). My use of CHAT in (this and other) research endeavours is anchored in a commitment to interrogating and intervening in the historically accumulated practices of teaching and teacher education, to better understand how teacher education can effect transformation in the practices of educators. Here, I employ three CHAT concepts in particular: mediation, re-mediation, and motive object of activity, which I explain before turning to my main line of argument regarding how the GTPA functions as a collaborative project across a range of scales to both enable and reflect teacher educator agency.

2 My Engagement in the GTPA Collective

Since the earliest stages of development of the GTPA, led by ILSTE, I have enjoyed a privileged status within the Collective. My role has been as an observer, sometime hands-on participant (in national workshops, occasional online meetings of the Collective, and some analytic activities to understand how the GTPA ‘works’), and as a contributor to occasional reflective dialogues with ILSTE colleagues leading the work. However, unlike other members of the Collective, I have had no responsibility for its direct design and implementation with preservice teachers, its negotiation within university systems and curricula, and/or the educative processes contributed to the Collective by ILSTE colleagues. This unique positioning has allowed me to develop both emic and etic perspectives on the trial and implementation of the GTPA. It has also allowed me to take note of emerging phenomena within the Collective, some of which are captured in Part 2 of this book. This chapter draws, therefore, both on these chapters and my own (inevitably subjective and incomplete) musings from 2015 to 2020.

3 CHAT as an Analytic Framework for Interrogating the GTPA as a Form of Practice

From the outset, the nature of practice has been central to my understandings of the GTPA. In this volume, we find the GTPA described as a discrete assessment requirement anchored in preservice practice (GTPA as ‘task’) and as a new set of practices in ITE (GTPA as ‘teacher education labour processes’). Initial teacher education involves multiple sites of practice within and outside universities (the inclusion of ‘teaching practice’ in the ITE curriculum is a giveaway), yet concepts of practice have not always been prominent in its imaginary. Historically, teacher education researchers have taken up a wide range of concepts and lines of inquiry in their attempts to explain the formation of graduate teachers (Murray et al., 2008). These include concepts of reflection, identity, and motivation, as well as curriculum-specific understandings in subject domains such as English and mathematics. Many of these investigations have been driven by a desire to respond to technical-rational assumptions about initial teacher education found in many policy frameworks (Nolan & Tupper, 2019) and/or overcome the ‘theory–practice divide’ that has long bedevilled discourses of ITE (Anderson & Freebody, 2012). Yet, from my point of view, concepts such as identity and reflection have often been taken up in teacher education in ways that fall into the same briar patch as the theory–practice divide: they continue to locate the locus for learning about teaching inside the head of the preservice teacher, rather than within socially situated, artefact mediated practice.

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) is a theory of psychological development anchored in examination of human social practices, particularly (but not exclusively) in workplaces. It pays attention to how people work together to get things done to maintain human life-worlds. Within CHAT, practice is always mediated by cultural tools (concepts and material artefacts) through the semiotic nature of these tools: concepts and artefacts are rich with historically derived meanings that can be taken up to design and make sense of practices. These practices can also be developed (re-mediated) through deliberate re-design of cultural tools to change their meanings or by taking up alternative meanings (e.g. when recent school leavers enter ITE and begin to construct alternative meanings about the familiar cultural tools of schooling from a teacher’s perspective).

According to a CHAT analysis, practices change and develop when contradictory aspects of practice that hinder the achievement of motive objects of activity (the aims or tasks that are the focus of practice) are identified and worked upon by people working together within or across work sites and systems. These work sites and systems can range in scale, yet all are characterised by norms of speech and action that distinguish one field of practice from another. The motive object of activity of initial teacher education programs could be characterised, for example, as the desire to produce graduates who have internalised the norms of teaching, encapsulated in the APST and other codifications such as practicum reports, and who can then externalise these norms appropriately in school settings. This externalisation may conform to historically persistent norms of practice or, where re-mediation has occurred or is ongoing, practices may differ from historical norms. In this way, re-mediation of practice to achieve desired objects of activity is both reflective of and constitutive of human agency.

The move towards TPAs in Australia was in response to a recommendation in the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) report (Craven et al., 2014). TPAs offer a response to a perceived hindrance to high-quality teaching as an outcome of teacher education, viz. the conviction that, despite the authorisation to teach conferred by their graduation and provisional registration, Australia’s teacher education graduates are not sufficiently ‘classroom ready’. Through the lever of mandatory accreditation of ITE programs (AITSL, 2015) the requirement to develop a new cultural tool—a final-year TPA—was imposed upon Australia’s ITE programs as (in CHAT terms) a new mediational means for the development of graduate teachers.

4 The GTPA as Mediational and Re-mediational Means for Preservice Teacher and Teacher Educator Practice

New cultural tools long to be populated with meaning, but in the early days of developing a new tool, these meanings can be unstable, contradictory, and vulnerable to the meanings historically attributed to similar or predecessor tools. This was the case with the GTPA. At the outset of the development of the GTPA, I heard many teacher educators (both within and outside the GTPA Collective) claim that introduction of a TPA would be a straightforward exercise, since most ITE programs already had some kind of capstone task (such as requiring preservice teachers to submit a portfolio of their practicum work samples aligned to the APST). By populating the new cultural tool with meanings transferred from existing cultural tools, practices could remain largely unchanged in the assessment of final-year preservice teachers’ ability to teach.

This transfer of existing meanings was not the vision of TEMAG (Craven et al., 2014). As Haynes and Smith relate (Chap. 16, this volume), the TPA is part of a suite of tools that aim to intervene in the existing norms of ITE in Australia. Australia’s politicians have invested these tools with meanings connected to raising the quality of teaching in the interests of strategically improving Australia’s global economic competitiveness and investments [notably since the Economics of Teacher Quality conference held at Australian National University in 2007 (for example, Ingvarson & Rowe, 2007); more recently in a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) review of the relationship between teacher quality, student outcomes, and overseas aid investment (Naylor & Sayed, 2014)]. These meanings are also historically derived, in part from the long anti-democratic project of attacks on universal schooling. This has particularly been the case in the US (McLean, 2017), and Doyle et al. (Chap. 5) explain the way critiques of the edTPA in the US preceded the development of TPAs in Australia, including the fear that they would “steer the work of teacher educators in managerial directions” (para. 4).

Such meanings continue to be roundly rejected by many academics, teachers, and school leaders in Australia and elsewhere. For example, Parks and Morrison (Chap. 7) note the way important stakeholders quickly attached meanings of this type to the GTPA. School personnel in their jurisdiction initially saw the GTPA “calling into question the competency and professional judgement of schools and experienced teachers, and excluding them from the teacher preparation process” (para. 15). Many such tensions arise in systems of practice when new cultural tools are ‘parachuted in’ from other practice systems, followed by a rush to attribute pre-existing meanings to their use. There is a long history of these kinds of policy disruptions in contemporary teaching and teacher education, often enforced by levers such as funding or, in the case of TPAs, accreditation. An urgent priority for the GTPA Collective at the outset was, therefore, to establish new meanings for the GTPA as a cultural tool with potential to re-mediate the practices of preservice teachers, teaching practice sites, and teacher educators.

The meanings that inhere in the GTPA for preservice teachers are not the focus of this chapter; suffice to say they are closely linked to the achievement of the relevant APST, including concepts and practices of planning, assessment, and moderation (see Chaps. 2 and 3). However, I did observe how the GTPA increased expectations of preservice teachers in one emphatic way, through a shift in meaning in relation to capstone tasks of this type: the GTPA demands that preservice teachers present a synthesis of their claims about their teaching (i.e. they provide evidence to think about, and simultaneously integrate, multiple dimensions of teaching practice, based on data they generated in the classroom). This differs from the teleological meanings often attached to requirements for evidence of preservice teachers’ reflective practice (e.g. responses to the question ‘What will I do differently next time?’).

Rather, my focus in this chapter is the way the GTPA both demanded and constructed new meanings in the mediation of teacher educators’ practices. A clear example, noted by Doyle et al. (Chap. 5), is the way fidelity became a central concept attached to the GTPA’s re-mediation of teacher educators’ practices. For the first time in the history of Australian teacher education, there was a requirement on ITE to engender confidence in the comparability of assessment judgements not just within single institutions but across diverse practice sites of ITE. How could such a complex outcome be achieved with fidelity?

Haynes and Smith (Chap. 16) describe the infrastructure needed to capture these assessment judgements and report them back to the Collective. They use the concept of performance trajectory in a way that situates the GTPA within a core commitment of teacher educators: that preservice teachers who enter our universities as nascent teachers will be able to teach confidently and competently by the time they graduate. This commitment is underpinned by an assumption of causality; what teacher educators (and their in-school colleagues) do causes preservice teachers to change, and develop new and appropriate practices of teaching. This assumption of causality in ITE echoes the synthesis demanded of preservice teachers by the GTPA, described above, whereby preservice teachers are required to articulate the complex relationships between their assessment practices, pedagogical judgements, subsequent actions, and the learning of classroom students (or the learning of preservice teachers, in the case of teacher educators). Other concepts that came to inhere in the GTPA are also described in the case examples in this volume. Dargusch et al. (Chap. 8), for example, explore the GTPA as an enabler of capable preservice teacher and teacher educator practice, while Lugg et al. (Chap. 6) argue for the GTPA as a site of resistance against the concept of teacher quality, arguing instead for teaching quality.

By contrast, Heck (Chap. 4) portrays an instructive counterpoint to the meanings ascribed to ITE in the way it is conceived through the GTPA. The data Heck presents portrays a political fetish with entry standards and recruitment of the ‘top students’ into ITE (Goss et al., 2019). The unspoken assumption here is that, if the ‘brightest and best’ can be recruited to enter ITE, the impact of Australia’s (presumed ineffective) ITE programs will at least be minimised; in other words, the call is for a return to ‘teacher quality’ rather than ‘teaching quality’. Heck ends on an optimistic note, arguing that future media representations should draw on research that shows the complexity of teacher quality. As the chapters in this volume show, instead of drawing on broad (and rather inchoate) concepts of quality, the GTPA has been populated with concepts such as fidelity, accountability, trajectory, identity, and capability within and across diverse sites of ITE. I count this as a major act of resistance to the meanings that mass media, policymakers, and (sometimes) schools have attempted to impose on ITE. So how was such an audacious move achieved?

5 The GTPA as a Multi-scalar Collaborative Project

My analysis of the chapters in this volume suggests that the GTPA was both the catalyst for, and enabler of (c.f. Dargusch et al., Chap. 8), multiple collaborative projects that occurred simultaneously and at a range of scales. Note I am using the term ‘collaborative project’ here in relation to its distinctive meaning within activity theory articulated by Blunden (2014). Blunden views collaborative projects as collective systems of action made coherent through mediation by a shared motive object of activity—the aims or tasks that draw practice forward in pursuit of desired outcomes—in addition to their mediation by cultural tools, divisions of labour, and other norms of practice. Collaborative projects may be motivated by practical, political, or ideological objects, and frequently seek to be deliberately transformative. Successful projects that begin with the pursuit of radical transformation can end in institutionalisation; a recent example in Australia is the campaign for marriage equality, which began in the localised collaborative projects of activists and ended in national legislation. As Blunden explains, “the project inheres in the artefact-mediated actions, norms, rules and symbols flowering from the project’s self-concept and underlying the actions which constitute the project” (2014, p. 9).

In the section of the chapter that follows, I consider the GTPA as a collaborative project across a range of scales—individual, intra-institutional, multi-institutional, and at a national systems level—before returning to my central claim about the GTPA as a site for reclamation of teacher educator agency.

6 The GTPA as a Collaborative Project for Preservice Teachers

A submitted GTPA is the property of an individual preservice teacher and is assessed on an individual basis. Yet it is impossible for a GTPA to be generated exclusively out of the work of an individual. Every GTPA contains traces of the voices of the preservice teacher, the students they have taught, sometimes of their supervising (mentor) teacher, and even of other teachers in the placement school. At a more inchoate level, GTPAs can also contain traces of conversations with university lecturers, exchanges with other preservice teachers, and engagement across space and time with the voices of theorists and pedagogues, some of whom are long dead. In this sense, an individual GTPA is an outcome of collaboration. But is the GTPA therefore a collaborative project for preservice teachers?

In the initial phases of GTPA development as a high-stakes complex performance assessment of graduate readiness to enter the profession, I argue this was not the case, at least by the definition I am using here. According to Holodynski (2014), collaborative projects.

…take up dissatisfaction with an existing (professional) practice. This is the case for many projects within the institutional contexts of kindergartens, schools and universities where the institutional learning and teaching have been judged unproductive and inappropriate. This dissatisfaction makes the persons affected (teachers, students, parents) receptive to a search for innovative and successful teaching and learning strategies and their testing. (p. 354)

While there is ample evidence for dissatisfaction with ITE as an originating force for the GTPA, there is no compelling evidence that preservice teachers sought out the GTPA as a collaborative project on the basis of dissatisfaction with their ITE programs. Rather, it was a task imposed upon them in the context of higher education assessment. Also, it is impossible to know what the motives objects of a specific preservice teacher might be and whether these motive objects of activity are socially shared as they undertake their GTPA. So, I think that it is reasonable to argue that the GTPA in its early instantiations, at least at the level of individual preservice teachers, was a polyvocal artefact but not necessarily a collaborative project. I return to this point at the end of the chapter to consider whether this is still the case, given recent shifts in the implementation of the GTPA prompted by the coronavirus pandemic described in Provocation 5 of this volume.

7 The GTPA as a Collaborative Project Within Higher Education Institutions

There is ample evidence in this volume of the way the development and implementation of the GTPA within ITE programs has met the minimal definition for a collaborative project. Dargusch et al. (Chap. 8), for example, describe the development of preservice teachers’ assessment practices through an account of intra-institutional ITE practice. As they explain, “the first phase [of the investigation they report] focused on the analysis of our [emphasis added] decision making with respect to implementation of the GTPA” (para. 13). Their account shows how processes of decision making were mediated by shared meanings anchored in the GTPA, notably the concept of assessment identity but also concepts of institutional reputation, preservice teacher capability, and the GTPA as a site of convergence for elements of ITE curriculum (see Table 8.3).

Doyle et al. (Chap. 5) also provide an account of an intra-institutional collaborative project, focused on collaborative professionalism as a motive object of activity, mediated by the GTPA. An important insight from their project is the way divisions of labour (who does what, and in what hierarchy of power and authority) are also critical to collaborative projects. They report the perspectives of sessional (i.e. non-tenured) teacher educators in GTPA implementation alongside those of tenured teacher educators (implying, inter alia, questions about the possibilities for successful policy intervention at the many teacher education sites where there is a heavy reliance on sessional labour). Chapter 5 also touches on the way in which different collaborative projects nested within single institutions (such as the work of ITE academics in overlap with the work of professional (administrative) staff responsible for the management of practicum placements) can converge in the pursuit of a common object; in this case, the shared object is the provision of teaching practice placements that afford preservice teachers the opportunity to complete a successful GTPA. However, as almost every chapter in this volume reflects, it is the inter-institutional nature of how the GTPA was developed and is sustained that is its most compelling feature.

8 The GTPA as a Collaborative Project Across Multiple Higher Education Institutions

The GTPA Collective began with two teacher education institutions in a pilot of the GTPA in 2016; at the time of writing, the Collective includes 18 institutions, almost half of the universities offering ITE in Australia. Adie and Wyatt-Smith (Chap. 2) provide a description of how the individual GTPA submissions of preservice teachers form the material means for collaboration across the Collective to ensure national consistency of teacher educator judgements against the Graduate Standard of the APST (AITSL, 2011). As Lugg et al. (Chap. 6) explain, “a unique characteristic of the GTPA is the process of moderation across the collective institutions to ensure shared interpretations of the GTPA assessment criteria” (para. 6). But can such a large collective work process necessarily meet the definition of a collaborative project, as outlined earlier?

Following Holodynski’s requirement for a “socially shared personal sense of the project’s goals” (2014, p. 355), I think the answer must be ‘Yes’. My reflections on the Collective’s regular face-to-face workshops and monthly meetings via Zoom™ suggest these were primarily a site for the negotiation of shared meanings to mediate the work of teacher educators in achieving a shared motive object of activity. These meanings were initially motivated by the desire to implement the GTPA as an artefact (i.e. a material instantiation) of teacher educator and preservice teacher practice. However, new meanings do not precede the construction of new artefacts; these develop simultaneously and dialectically through exploration and use. So, as questions were asked about seemingly pragmatic aspects of the GTPA (What should be the maximum permitted page length? What relative weightings should be given to its various components?), these temporary practice problems were actually the catalyst for anchoring shared meanings of concepts such as moderation (see Chaps. 3 and 6), synthesis, identity (Chap. 8), fidelity (Chap. 5) and trajectory (Chap. 16), within both the GTPA as a task for preservice teachers and the GTPA as a new form of teacher education practice.

9 The GTPA as a Collaborative Project at a National Systems Scale

Simultaneous with these developments, members of the Collective were inevitably also interacting with other stakeholders in Australian ITE who were not privy to these practice conversations. Schools, universities, teacher education programs, teacher unions, curriculum authorities, and teacher regulatory bodies may reasonably be considered large-scale collaborative projects, but they do not necessarily share the same motive object of activity (notwithstanding they may share a desired outcome of high-quality education for all Australian students). The imposition of TPAs in Australia demanded that these disparate motives be brought into sufficient alignment to allow preservice teachers to successfully undertake a GTPA accompanied by national-level confidence in the assessment of their work. Wyatt-Smith and Adie (Chap. 1) touch on some of the concepts that have attached themselves to political concerns about ITE internationally, such as impact, accountability, competence, readiness, and compliance, each of which had major implications for the development of a GTPA that would be generative for preservice teachers, build public and political confidence in the work of ITE, and respect the accumulated expertise of teacher educators (see also Heck, Chap. 4). This required that the negotiation of meanings in relation to the GTPA would not only establish new meanings but renegotiate some sedimented and unhelpful meanings of historically contested concepts such as accountability.

The initial difficulties reported by Parks and Morrison (Chap. 7), discussed earlier in this chapter, reveal the way this re-negotiation of outdated meanings attributed to the GTPA (i.e. its role in re-mediating ITE practice) was ultimately enabled by the convergence of collaborative projects with salience for ITE within and across jurisdictions. Parks and Morrison adopt the concept of the GTPA as a ‘boundary object’ to theorise how this was achieved, and argue that meanings inhering in the GTPA developed as it encountered ‘crossing points’ between related collaborative projects. The real significance of their chapter, however, is the way it shows how the work of universities, teacher education programs, schools, and teacher registration authorities can be brought into productive alignment if they share a sufficiently powerful motive object of activity; Lugg et al. (Chap. 6) call this a “common purpose” (para. 44). In the case of Tasmania, this motive was the need to alter a persistent historical trajectory of teacher shortages. On the national scale, Wyatt-Smith and Adie (Chap. 1) relate that.

Since the introduction of competence assessment in Australian teacher education, we have considered ourselves to be working in a discovery project that has required ongoing collaboration across the country. It has also required ongoing and significant learning by all parties, including teacher educators, preservice teachers, policy personnel, school personnel, and a multidisciplinary team of researchers and methodologists. (Wyatt-Smith and Adie, para. 17)

To summarise, I have argued that GTPA implementation was not only the catalyst for the formation and convergence of new and existing collaborative projects, but that the GTPA itself has been a potent artefact in the negotiation of new meanings in relation to ITE practice in Australia. Such collaborative projects—according to Blunden (2014)—provide the appropriate unit of analysis for empirical and theoretical work in understanding human practices. It is worth quoting Blunden at length here, with the suggestion that the reader substitute ‘the GTPA’ for ‘the project’ throughout the following:

In the course of their development projects objectify themselves, and there are three aspects to this objectification: symbolic, instrumental and practical. Firstly, the moment someone first communicates the concept of the project it is given a name or symbolically represented in some other way, after which the word or symbol [for example, the GTPA as a noun] functions as a focus for actions. The word eventually enters the language and acquires nuances and meanings through the development of the project and its interaction with other projects and institutions. Secondly, the project may be objectified by the invention and production of some new instrument or by the construction of material artifacts [e.g. the GTPA as an artefact] which facilitate or constrain actions in line with the project and facilitate its integration into the life of a community. … Finally, and most important is practical objectification: once the project achieves relatively permanent changes in the social practices of a community, the project transforms from social movement into customary and routinised practices – an institution. In this instance, the word may be taken as referencing the form of practice in which the project has been given practical objectification and normalised [for example, the GTPA as ITE practice]. (p. 10)

The chapters in this volume capture various aspects of the GTPA as a collaborative project as it has progressed through these three phases. However, no project of this scale and significance can progress through these stages without significant personal sense-making and emotional commitment on the part of participants (Holodynski, 2014). In the next section of this chapter, I return to my claim that the GTPA has played a critical role in achieving a significant motive object of activity for the GTPA Collective: to reclaim the agency of the participating teacher educators.

10 The GTPA as a Site for Reclamation of Teacher Educator Agency

Several of the chapters in this volume summarise the international political and bureaucratic preoccupation with ITE in recent decades. Consequential policy reforms, particularly when combined with reform of research management and metrics in universities in recent years and with negative media portrayals (see Heck, Chap. 4), have been dispiriting for many teacher education academics (Zipin & Nuttall, 2016). Yet the chapters in this volume suggest the development and implementation of the GTPA in Australia has had the opposite effect for many of the teacher educators who participated in the Collective. There is evidence the GTPA has been the catalyst for a renewal of teacher educator agency, both with respect to themselves as educators and with respect to significant stakeholders. Here I explain how such a repositioning might be understood from a CHAT perspective.

In keeping with the CHAT concepts already employed in this chapter, I argue the experience of increased agency reported by teacher educators in the Collective relies, first, on re-mediation by cultural tools and, second, on opportunities to take an authoritative stance with respect to motive objects of activity. In relation to cultural tools, as Parks and Morrison explain, “importantly, the GTPA Collective provided critical resources, perspectives and contributions [emphasis added] to teacher educators in order to initiate the relational work required to implement the teaching performance assessment within the complex and contested teaching and learning contexts” (Chap. 7, para. 19). These resources could then be mobilised in these relational work contexts to support an authoritative stance on the part of teacher educators. Doyle et al. (Chap. 5) explain the nature of this opportunity in relation to the fidelity of implementation of the GTPA:

As such, the teacher educators’ careful development of the academic program is seen as critical to steering the collective initiative at the university, so as to avoid a collision between the four key sites of practice (the ITE academic program, the school-based professional experience program, the requirements of a TPA, and the assessment policy of the university). (para. 15)

I read this quote from Doyle et al. as an example of how key concepts inhering in the GTPA (in this case, fidelity of implementation) provided the authoritative basis for negotiations with significant adjacent and overlapping collaborative projects, such as teacher registration authorities. In these negotiations, teacher educators became “critical to steering the collective initiative at the university” (para. 15). Sannino and Ellis (2015) identify the importance of collective creativity in responding to social challenges, but collective creativity (which I equate with Doyle et al.’s “collective initiative”) can only be fully realised where there are powerful motive objects of activity and meaningful cultural tools available to mediate and re-mediate collective work. A core principle of CHAT is that by changing cultural tools, humans can change themselves from the outside (Daniels, 2004) because their practice is re-mediated by the changed tool. Lugg et al. (Chap. 6) report that “our experiences of working in the GTPA Collective highlighted that engagement with developing, refining and implementing the instrument has enhanced our professional development as teacher educators” (para. 31). This reference to the development of the authors as teacher educators speaks directly to the way re-mediation of practice necessarily also changes the participants in the practice.

11 Conclusion

In this chapter I have argued, on the basis of the chapters in Part 2 of this volume, that the GTPA not only constitutes a collaborative project in activity-theoretical terms, but has fostered related collaborative projects that overlap locally as well as on a national scale. In line with a CHAT theorisation, I have argued that collaborative projects can only be considered as such if they articulate shared motive objects of activity and strive to populate critical artefacts (the GTPA in this case) with meanings that can mediate and re-mediate the practices of members of the collaborative project. An effect of this re-mediation, as related by members of the GTPA Collective, has been to enhance their agency as teacher educators through increased capacity to take an authoritative stance in relation to the development of graduate teachers.

In keeping with the provocative nature of Part 3 of this volume, I return to a provocation of my own, foreshadowed in my earlier claim that, for preservice teachers, the GTPA task did not meet the minimal definition for a collaborative project in its initial instantiations. My provocation was to suggest that, irrespective of the rich collaborations underpinning each GTPA, since the GTPA is submitted and assessed on an individual basis, it does not meet Blunden’s (2014) minimal definition for a collaborative project at the level of the preservice teacher.

This may appear to be something of an ultra-fine distinction between preservice teacher’s practices of constructing their GTPA (which are necessarily collaborative) and their motive object of activity (which can only be individual, since they are required to submit the assessment on an individual basis). However, this distinction is not peculiar to the GTPA. Judgement of preservice teacher work at the individual level is a structural feature of ITE, undergirded by the responsibilisation of individual teachers that is characteristic of policy and the APST. However, this practice aligns poorly with the collaborative demands of actual teaching in contemporary schools. How, then, might the GTPA be conceived as a truly collaborative project for preservice teachers, one that not only reflects their capacity to collaborate (the GTPA task already allows them to do this) but is itself an enactment of collaboration in its preparation and submission, so that their experience is more authentically like the experience of teaching as a collaborative project?

Provocation 5 of this volume describes one way forward. Rapid adjustments in the implementation of the GTPA due to school closures were necessary in response to the crisis in teaching practice placements imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in Australia on 25 January 2020. This crisis represented more than a dissatisfaction with present circumstances (Holodynski, 2014). COVID-19 demanded an overthrow of the most basic assumption about how preservice teachers demonstrate ‘classroom readiness’: that it can only be done in a ‘real’ classroom. A central feature of these adjustments was the creation of online ‘data scenarios’ that represented the demands of in-school GTPAs. The salient point about this approach, in the context of the present chapter, is the way these scenarios made available to preservice teachers the work of their peers as the basis for these representations. I argue this marks a watershed moment in the education of graduate teachers. While some preservice teachers have, no doubt, had access to the work of their peers before, no teacher education project has enabled distributed peer-to-peer collaboration on such a scale or in such a systematic way. In activity-theoretical terms, this strategy represents distributed cognition on a wide scale across a single group of participants in the GTPA with a single shared motive object of activity: the successful completion of the GTPA task as a collaborative project by preservice teachers as they contribute to the ongoing life of the teaching profession.

In this chapter I have argued for the way the GTPA is overturning the long historical commitment to the individual as the appropriate unit of analysis for the investigation of human development, historically promulgated by developmental psychology. I have presented an alternative view, drawing on CHAT and Blunden’s (2014) conceptualisation of collaborative projects as the most meaningful way to understand the development of human practices. There is already evidence, presented in this volume, from the GTPA Collective that multiply-mediated, object-oriented collaboration can transform the practices of individuals and systems alike in ITE as an aspect of ongoing human practice.

Notes

- 1.

Acknowledgment: The Graduate Teacher Performance Assessment (GTPA®) was created by the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education, Australian Catholic University and has been implemented in a Collective of Higher Education Institutions in Australia (www.graduatetpa.com).

References

Anderson, M. J., & Freebody, K. (2012). Developing communities of praxis: Bridging the theory practice divide in teacher education. McGill Journal of Education, 47(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014864ar.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2011; revised 2018). Australian professional standards for teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2015, revised 2018, 2019). Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia: Standards and procedures. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programs-in-australia.pdf?sfvrsn=e87cff3c_28.

Blunden, A. (Ed.) (2014). Collaborative projects: An interdisciplinary study. Brill.

Craven, G., Beswick, K., Fleming, J., Fletcher, T., Green, M., Jensen, B., Leinonen, E., & Rickards, F. (2014). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group, TEMAG. Department of Education. https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/action-now-classroom-ready-teachers-report.

Daniels, H. (2004). Activity theory, discourse and Bernstein. Educational Review, 56(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031910410001693218.

Engeström, Y. (2014). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Goss, P., Sonnemann, J., & Nolan, J. (2019). Attracting high achievers to teaching. Grattan Institute.

Holodynski, M. (2014). Emotional commitment and the development of collaborative projects. In A. Blunden (Ed.), Collaborative projects: An interdisciplinary study (pp. 351–355). Brill.

Ingvarson, L., & Rowe, K. (2007, February 5). Conceptualising and evaluating teacher quality: Substantive and methodological issues. Paper presented to the Economics of Teacher Quality conference, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.

McLean, N. (2017). Democracy in chains: The deep history of the radical right’s stealth plan for America. Duke University Press.

Murray, S., Nuttall, J., & Mitchell, J. (2008). Research into initial teacher education in Australia: A survey of the literature 1995–2004. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.013.

Naylor, R., & Sayed, Y. (2014). Teacher quality: Evidence review. Office of Development Effectiveness, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/evidence-review-teacher-quality.pdf.

Nolan, K., & Tupper, J. (Eds). (2019). Social theory for teacher education research: Beyond the technical-rational. Bloomsbury.

Sannino, A., & Ellis, V. (Eds). (2015). Learning and collective creativity: Activity-theoretical and sociocultural studies. Routledge.

Zipin, L., & Nuttall, J. (2016). Embodying pre-tense conditions for research among teacher educators in the Australian university sector: A Bourdieusian analysis of ethico-emotive suffering. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1177164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nuttall, J. (2021). The GTPA as a Collaborative Project in Australian Initial Teacher Education: A Cultural-Historical Activity Theory Perspective. In: Wyatt-Smith, C., Adie, L., Nuttall, J. (eds) Teaching Performance Assessments as a Cultural Disruptor in Initial Teacher Education. Teacher Education, Learning Innovation and Accountability. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3705-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3705-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-3704-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-3705-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)