Abstract

The new OFSTED framework gives an opportunity to re-evaluate what it means to learn a discipline and why that might be important and helpful for young people. The ‘powerful knowledge’ thesis of Michael Young has been criticised, but can be given a benign reading. Deep subject learning is both liberating and something for life. There may be an opportunity at hand to rethink Catholic education in terms of a new Christian humanism. We conclude with an exploration of what humanistic ‘deep learning’ might mean for Religious Education in Catholic schools today.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Religious education

- Knowledge-rich curriculum

- Cultural capital

- Subject discipline

- Deep knowledge

- New christian humanism

Introduction

This chapter explores the implications for curriculum planning in Catholic schools in general and Religious Education in particular in relation to the new OFSTED framework and the ‘powerful knowledge’ hypothesis that lies behind it. It concludes with an outline of what a discipline-based Religious Education might look like across primary and secondary education in the UK and invites discussion of the suggestion.

The reflections and questions addressed in this chapter are personal and have been stirred by a number of different factors. Firstly, I am sitting on a local SACRE1 committee, trying not to look too obtuse. There I have been made aware of the newly significant status that RE is being given in the latest OFSTED framework for inspecting all state schools in England.2 Not only is it to be intellectually robust, but it is as likely to be inspected and evaluated for its place in a carefully constructed curriculum as any other subject. Though RE in Catholic schools has its own inspection procedure, the shift in OFSTED’s valuation and its inspection priorities are likely, I would expect, to have a positive effect on its status in Catholic schools, and eventually to have an effect on the way it is evaluated in the Section 48 inspections. This may be overoptimistic. Other concerns have been identified (for example, Whittle 2018) for Religious Education due to pressure from EBacc subjects and the narrowing of the Sixth Form curriculum. Whether the new framework will mitigate that remains to be seen.3 Secondly, Philip Robinson, the National Religious Education advisor of the Catholic Education Service in England, has throughout 2019 and 2020 been running a wide-ranging consultation exercise in the run-up to a detailed revision of the English and Welsh Bishops’ Curriculum Directory for Religious Education4. In the two meetings I have been privileged to attend (the theological working group), a significant discussion has centred around Michael Young’s notion of ‘powerful knowledge’ and the related question of how Religious Education fits in with the academic discipline of theology.5 The value and meaning of the term ‘powerful knowledge’ and the soundness of the idea of ‘disciplines’ that goes with it has received some hefty challenges.6 Nevertheless, I believe it can be given a benign reading, and it is this that gives the ‘Religious Education as a discipline’ in the title of this chapter. Finally, I have been fortunate enough to be able to visit a Multi-Academy Trust run by an old friend, where some of the ideas about curriculum, valuable knowledge and subject integrity that lie behind the new OFSTED framework (and potentially the evolving Curriculum Directory for Religious Education) are being put into practice in an area of England where social deprivation is high and educational standards have been historically dismal. I saw enough on my brief visit to catch a glimpse of what carefully structured learning, beginning at the primary level, could mean for giving educationally impoverished children real cultural capital and a sound basis for a deep understanding of subject disciplines.

When I read the new OFSTED framework, I almost began to think it might be worthwhile going back into secondary teaching. Things that I had found difficult to comprehend, let alone deliver (internal targets based on near-meaningless, and often dishonest micro-levelling), were now off the table. The structure of individual lessons and the methods used for pupil feedback were no longer prescribed. Teachers’ lessons would no longer be graded. ‘Different approaches to teaching can be effective’.7 Hallelujah. The general approach to inspection seems to be pragmatic and evidence based. Though (inevitably with a government document) the menace of ‘the highest possible standards’ always lurks in the background, for a government document the following is not a bad educational aim, and does take us beyond the narrow focus on exam success.

Our understanding of ‘knowledge and cultural capital’ is derived from the following wording in the national curriculum: ‘it is the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing them to the best that has been thought and said, and helping to engender an appreciation of human creativity and achievement. (Ofsted Inspection Framework 2019 p. 4) 8

Now I do have a fact-averse philosopher’s wariness about the rather Gradgrindy obsessions of the historian and cultural conservative former Education Secretary Michael Gove, who drove the exam reforms and put ‘powerful knowledge’ and ‘cultural capital’ on the agenda. I am also anxious that a drive to master facts diminishes the space for the kind of exploratory learning that is both more enjoyable for teacher and student, and potentially builds a much deeper relationship between student and subject than merely being told stuff to memorise.9 However, Michael Young offers a more subtle and appealing account of what powerful knowledge might mean in state education that goes beyond the thousand facts you need to know in order to be a successful Englishman, and offers a fruitful way of interpreting those new criteria.

If I understand Young correctly, all students of whatever background should be given a soundly structured and pedagogically creative access to culturally crucial disciplines.10 That access should grow within the (fluid) logic and the agreed factual basis specific to the discipline, preserving its integrity but acknowledging its openness to new developments from the community of experts. Offering weaker students skills-based courses, in which content and cohesion of ideas do not matter, in the end does them few favours, because it deprives them of the deep knowledge and understanding of crucial areas of human enquiry that will enable them to interpret their world as well as any of their contemporaries.

Now John White, a leading British philosopher of Education, raises real concerns about the coherence of the very idea of ‘powerful knowledge’. He challenges the insistence on specialist vocabulary, the implicitly essentialist notion of disciplines, the idea that within them can be found a canonical set, constituting an educationally desirable ‘cultural capital’, and the assumption that knowing lots of things is of itself the most important goal in education.11 It is worth remembering the importance both of the active engagement of the learner in investigating the world, and of ensuring that the view from below is acknowledged and included in a true, transformative Christian education. There are versions of a canonical ‘cultural capital’ and pursuit of the highest standards that would exclude both of those crucial goals.

In spite of this, I am still drawn to the notion of ‘powerful knowledge’ as at least a helpful heuristic concept. White objects that Young’s notions of essentially discipline-specific vocabulary, and knowledge that cannot be derived simply from the student’s own experience only really apply to the hard sciences and to mathematics. Great literature is most certainly accessible from experience and without a vast technical vocabulary. Indeed, if one were to exclude personal experience, you would exclude that ‘see, judge, act’ process described by Raymond Friel12 and the sort of transformative readings of scripture, central to the Liberation Theology movement, which over the years has helped the Catholic hierarchy to re-evaluate its relationship with oppressive secular powers.

However, anyone who cares about their subject will recognise, even if it is difficult to formulate sometimes, that there are better and worse ways of going about it.13 There are people who are really good at it, and there are those who don’t really get it. There are those who think well and responsibly and creatively within a discipline, and those whose thinking is shallow or careless or narrow. It is the last, I think, that is really important for understanding what a benign version of ‘disciplinarity’ might mean, and applies equally to liberal arts, metalwork, music and the hard sciences. A discipline has to recognise that it does not know everything, has not said everything, may have got things wrong, needs to be open to new information and can learn things from the way other disciplines operate. All disciplines have a family resemblance in this respect (I am going for Wittgensteinian definition rather than Platonic definition) and though they will have their characteristic areas of enquiry and characteristic methods, many of these will overlap. Things that you need to know in chemistry will also be important if you are to really understand what you are doing when you work with resistant materials. Psychology, sociology and history provide a mutually enriching exploration of themes that also appear in Greek tragedy.

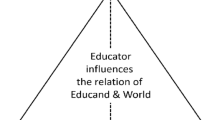

Learning to do things well is real and empowering. It takes you from where you are familiar with things, to new places where you have to learn to be at home. It is also often hard.14 Practising times-tables, verb tables and musical scales is tedious at times, but it eventually pays dividends in the power to manipulate equations effortlessly, to communicate accurately and to make sweet melodies. My power to think well and deeply about literature increases when I am introduced to the professional language and work of thoughtful commentators. Mastering the syntax of a language is at once a struggle and liberating. In fact, if one wanted a model for a benign reading of what ‘powerful knowledge’ is about, it might be learning to speak a language well (including one’s home language). The process of learning is never actually divorced from our experience but entails encountering tough, non-negotiable new things to remember and practise (it is a mistake to think of linguistic knowledge—and perhaps any knowledge—primarily as propositional data) but it ends with a suppleness of communication that enables us to say, and often see new things in a larger world. Because all learning is ultimately a human activity, it is made easier by teachers who are great communicators and good human beings who not only teach the discipline, but in some sense also model it.15 The end product is someone who can work well within a discipline, has a deep understanding of it and cares about it.16

This model places huge demands on teachers in terms of subject knowledge and pedagogical imagination and skill—and on the pupils who will struggle with material which is genuinely hard to grasp. Nevertheless, such an approach that prioritises the integrity and value of each subject over generic skills will be attractive to any teacher who cares about their subject. Attractive too is the notion that the goal of teaching, say English, is not to give them an exam credit in a key subject, but to enable them to enjoy going to watch Macbeth when they are in their forties. That is entirely in accord with the humanist tradition of education, whether Christian or secular.

One of the striking features of the transformation in OFSTED’s approach is a shift away from judgements based on the form and structure of individual lessons to judgments based on lessons understood as an element within the architecture of a whole curriculum. Instead of looking for a learning leap that has to happen for all pupils in these 50 min, the inspectors will be looking for activities (including standing in front of a blackboard with a bit of chalk) that have a clear place in the process of acquiring and reinforcing the facts and ideas essential to becoming masters of a subject. The emphasis is on long-term memory and deep connexion, rather than short-term, disconnected ‘wow’s (though these will obviously continue to have their place, as they always have).17

Among the implications for curriculum planning are that the process has to begin at primary school. Inequality in educational outcomes at the secondary level has much to do with the huge divergence in language acquisition and vocabulary during those years that often depend on family background. That has to be intentionally compensated for across subjects. In some subjects (primarily maths, physics and chemistry), there are well-trodden and reliable paths that structure and reinforce learning. In others (languages, humanities), it is much less clear either because of ideologies of the method (in the case of languages and English) or because of problems of volume. Decisions have to be made about what is most worth knowing, or what is going to be most helpful in providing an interpretative framework for lifelong learning. These would fall under White’s ethical educational choices, where enfleshing the bare heuristic concept of ‘powerful knowledge’ is subject to a judgment that may be interdisciplinary, but moves into a realm of value that goes beyond any one of them.

Towards a Catholic Curriculum?

There is a very interesting opportunity here for Catholic educational institutions to rethink the architecture of their whole curriculum, perhaps to create a new, open Christian humanism that helps their students—of a mixture of faith backgrounds—to live good, thoughtful and compassionate lives in the twenty-first century. But what might that mean specifically for the subject (or discipline) of Religious Education?

One attraction of the new inspection framework is that it offers ‘intellectual rigour’ and the possibility of introducing age-appropriate real theology, at the different key stages. This could be immensely helpful for students as they move from the early years of primary school, where religion is a given, through to older years where simply formulated religious ideas begin to run up against challenges from other subjects and from the wider world. What, however, is real theology? And what tools do we need to give people by way of induction into a (potentially) lifelong exploration of this particular craft?

Here, we run up against a fundamental problem of Catholic Theology (and perhaps theology in general) that it is not a single discipline, but a loose conglomeration of disciplines that do interrelate, but that have different criteria of evidence and truth. There is then, of course, the further problem that modern theological debate, which often brings those differences into relief, rarely makes an appearance in general Catholic discourse. This unevenness in the disciplines of theology (which certainly requires fairly sophisticated metacognition) is ironed out in the language of the Catechism, which, while providing the historical justifications for dogmatic conclusions is understandably coy about higher-level questions of method, interpretation and epistemology.

So one interpretation of ‘real theology’ for Catholics might be this flat space-time theology of the Catechism, which aims to cover all bases and implies its own sufficiency. This is certainly what the current Curriculum Directory for Religious Education asks for, adding in John Paul II’s ‘Theology of the Body’ as the basis for justifying Catholic teaching on sex and relationships, and including significant references to religious art. The current GCSE Religious Studies examination has papers specifically marketed at Catholic schools and reflecting what is required by the current directory. The result is an exhaustingly wide-ranging course. In fact, an increasing number of schools opt to start the GCSE in Year 9, and thus devote three school years to gaining this qualification. The GCSE RS course introduces students to a large technical vocabulary, key names and ideas in the history of doctrine (such as Augustine, Irenaeus, and Aquinas) and the importance of magisterial teaching, as well as some tools to make sense of ecclesial architecture and sacred art. In the textbooks published since 2016 (such as the AQA course book by Towey and Robinson 2016), there is notional room for debate. However, any substantial critique of claims attributed to Catholicism would have to be provided by the teacher. In the crowded specification for RS GCSE, it is difficult to see if there is actually any time allowed for this debate. There is little hint in the text that there might be a reasonable diversity of views among Catholics.

It seems to me on the whole, though, that this is to an extent an admirable endeavour. It does offer students ‘cultural capital’ and a sound basis for reflecting on their faith (or for non-Catholic students to have a substantial idea of what Catholicism is about). However, is it intellectually rigorous? If you view it from a historical or merely descriptive perspective, it probably is. And here we can notice that the aims of a secular religious education that needs to present a set of commitment-neutral uncontroversial ‘facts about’ a given religious group chime in very nicely with a catechetical approach that would like to deliver, well, religious ‘facts’. Here are key religious texts of this confessional group; these are their rules of interpretation and this is what the texts tell us. Now we have learned all the internal ‘facts’ of this faith that you need to know. No one gets hurt, or challenged to think more deeply.

This, then you might say, is intellectual rigour in the sense of ‘learned’. Does it give the students powerful knowledge? I would suggest both yes and no. Anyone who has done such a course has much more ammunition for a discussion when a Jehovah’s witness comes knocking on the door than might have been the case under previous exam regimes. Does it give them the intellectual tools for engaging fruitfully with sophisticated secular critiques or making sense of a multi-faith environment—or indeed for doing biblical hermeneutics and exploring modern Christologies? Not unless they have a teacher who takes them way beyond what the course demands.

I am reminded of the way my father was able to explain to me in enormous detail (when I was 10) and with great assurance the metaphysical framework for understanding transubstantiation in terms of substance and accidents. However, for me that language had no connection with anything else I was learning about the world. Even when I read Aristotle’s physics in my twenties, I couldn’t match it up with Aquinas—it is only 50 years later, after reading Avicenna that I finally understand where Aquinas is coming from. But still the gap between modern and ancient metaphysics remains, however ingenious the internal argument of the latter. The catechism-based course, for all that it is wide-ranging, apart from the occasional chink of light (such as the discussion of evolution) suffers from something of the same complaint.

Maybe this is an appropriate staging post for the Religious Education journey of 16-year-olds, but does it tell them that it is a staging post? That there is more to be learned, that they should be inspired to go on seeking? Could not carefully selected elements of the fact-based material be delivered at an earlier stage, opening a way for a deeper reflection on fewer core elements at Key Stage 4 (for 15- and 16-year-olds)? Is there an appropriate architecture for those 12 years of RE that would deliver a different sort of intellectual rigour? Such a rigour might be perilous for a purely catechetical faith, but may be crucial for developing a faith with intellectual integrity in the modern world and one which, for the many who will abandon the catechetical faith anyway, would give a reason to continue to engage with the mysterious transcendence offered within this (or any other) faith tradition?

A Possible Way Forward

I conclude with a loose account (not especially original) of how to think about theology as a discipline and what that could mean for the architecture of a 12-year programme that would be a gradual induction into that discipline. It does not go into the pedagogical details.18 First observation: theology is a human activity older than Christianity. This needs to be acknowledged. Second observation: theology has three main drivers.19 To continue, in some way, any ‘intellectually rigorous’ approach needs first to make people aware of those drivers, and second to reflect on their power to convey the truth about the way things actually are:

Driver one: The experiences of individuals and communities in specific environments that are understood as encounters and communications with a transcendent other, and that are consolidated in standard explanatory narratives linking individuals, communities and the wider world. (Examples include the Exodus Story, the Gospels, and the Iliad)

Driver two: The awareness of inconsistencies in the body of received narratives or dissonances with wider experience, and the desire to find some resolution to those inconsistencies. The troubled believer seeks a version of the story with a deep internal logic underlying the superficially inconsistent narrative fragments. (Examples include Aristobulus the Jew on the manifestations at Sinai, Paul’s letters to the Romans and to the Corinthians, the battles of Nicaea and Chalcedon, the hagiographical account of Joseph in the Quran, Rabbinic debates about the meaning of the sacrifice of Isaac, Aeschylus’ Oresteia, and the Upanishads)

Driver three: The need to defend the stories of the tradition from detractors or competing narratives and thought systems (examples of this process: Aristotle and Plato, the book of Wisdom, Justin Martyr, Origen, the Kalam theologians, Aquinas, Luther, Chesterton, Lewis). Inevitably, the language of the challenger’s argument becomes entangled with the home discourse. We can be more or less open to acknowledging such debts to others.

Here, then is my suggestion. In some way elements of these three approaches need to be rehearsed in an age-appropriate way throughout the years of primary and secondary Religious Education. Maybe we can think of theology as a complex journey that leads us from narrative and community through apologetic analysis only to lead us back to a narrative and a community in a new intellectual peace with integrity. Sometimes this will be the same narrative and the same community as you started with—but not always.

So it is probably worth stating honestly (this is a big ask for bishops) that the outcomes of well-constructed Catholic RE allow for a thoughtful and (if done well) respectful departure from the Catholic tradition (accent on the thoughtful). By this reckoning, James Joyce and Voltaire are successful products of Catholic education.

The underlying framework should clearly not be catechetical apologetics whose end is assent to the propositions of whatever is the current Catechism. Firstly, that would be difficult for staff who do not share Catechism positions. Secondly, it would be to abandon at the outset a large part of what any reasonable person might regard as ‘intellectual rigour’. Thirdly, the place for catechism is confirmation programmes. Rather, the framework should be a critical apologetics, which is honest about ambiguities and inconsistencies and is able to own up to the areas where answers are incomplete or inadequate. This will be particularly important in guiding the material prepared for many non-Catholic and non-specialist teachers, and will free them to answer the challenging questions thrown at them by pupils with integrity.

Such a course would begin (as currently, but perhaps more systematically) by building up a symbolic language for key notions like ‘salvation’ or ‘redemption’ through narrative, with increasing analytical sophistication as the years progress. With a little ingenuity, a sense of a historical arc and the place of Christianity and other world religions within it may be achievable for many students by the end of Key Stage 3 (when pupils are 14). Exploration of the sacraments, as the primary place where students will interact with official Catholicism, and a working understanding of ‘Trinity’ and ‘Incarnation’, ‘Creation’ may also be achievable by this stage. It would then be possible to take sample topics and deal with them in depth at Key Stage 4, rather than attempt to cover all bases. That depth would include more on the phenomenology of religious experience, and the relation of Catholicism to other faiths. It is crucial to reflect profoundly on the relationship between belief and lived experience, if RE is to be a life-enhancing rather than a hollow academic exercise. It would include a reflection on the interpretation not only of scripture, but of the magisterium, and would engage seriously with alternative non-religious world views—particularly when reflecting on ethical issues.

Broadly the movement of the curriculum would be from theological concepts rooted in narrative, through the puzzles and paradoxes these generate, to self-aware, or critical apologetics that is able to engage fruitfully with the wider world, and thus provides the basis for a lifelong search for understanding.

I would add that such an open Religious Education programme in a Catholic school presupposes a parallel retreat and a liturgical programme offering the sort of experiences that give some existential meaning to and material for the ‘intellectual’ pursuit of knowledge and understanding. We don’t want to drive people out of the faith by the cold pursuit of reason, or by the death of a thousand facts. Ideally, we want to help young people find their way of making an ever more mature, credible sense of their faith as something that already matters to them. But if this is not possible, at the very least we want to leave people with an understanding of and respect for the integrity of Catholic Christianity and of alternative world views that will help them to interpret and act in the world with responsibility and compassion.

Notes

-

1.

A SACRE is a Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education, and in the United Kingdom, they are an independent body which considers the provision of religious education in the area under the jurisdiction of its Local Authority, advising it and empowered to require a review of the locally agreed syllabus for Religious Education.

-

2.

See School Inspection Handbook at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-eif, §§ 33—38; in §§ 98—101 (on systematic lesson visits within a single subject area), the implication is that any subject (thus including RE) can be the object of such inspection (at least within non-faith schools); § 168 highlights spiritual and moral development as a decisive factor; § 174 insists on the ‘basic curriculum’ including RE and sex-and-relationships education; § 183 (implementation and quality of teaching) applies to all subjects equally; although much is made of the EBACC (which excludes RE) §§ 220—221 (spiritual and moral development) imply a robust RE programme and in § 226 RE is identified as an important area of inspection with pupil development; it should be noted that the Sect. 8 inspection document, more restricted in scope to monitoring schools on the edge, does not make specific remarks about RE or spiritual and moral development.

-

3.

See Whittle, Religious Education in Catholic Schools: Contemporary Challenges (2019). Whittle does note a changing social and political context, which makes good RE teaching an important potential contributor to social cohesion. This is perhaps what lies behind its prominence in the new OFSTED framework, which no longer allows schools simply to ignore it in favour of EBacc subjects.

-

4.

Robinson was also involved in helping produce specifications for the first wave of content-rich public exams after the Gove reforms introduced from 2016.

-

5.

See Young and Lambert, Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice (Bloomsbury: London 2014).

-

6.

See John White, “The Weakness of Powerful Knowledge” in London Review of Education, July, 2018.

-

7.

For more information, see the School Inspection Handbook §88.

-

8.

For more information, see the School Inspection Handbook §178. We also find a refreshing acknowledgement at §193 ‘National assessments and examinations are useful indicators of pupils’ outcomes, but they only represent a sample of what pupils have learned’.

-

9.

My reading of the OFSTED document is that it is actually much more subtle and thoughtful in its approach to what memory and knowledge are about than the rote-learning to which people like me are instinctively allergic. See School Inspection Handbook §183.

-

10.

For more information, see the Knowledge and the Future School, 67–88.

-

11.

See White’s article cited above.

-

12.

Unpublished paper from the annual conference for the Network for Researchers in Catholic Education at DCU in October 2020.

-

13.

As a would-be philosopher, I have particular issues with the reduction of the subject in some exam boards to a series of ‘for’ and ‘against’ propositions that could as easily be generated by my laptop as by a student.

-

14.

Willy Russell’s Educating Rita, and Stags and Hens are an entertaining and thought-provoking reflection on the benefits and hardships of being taken beyond your local cultural identity into the wider world.

-

15.

This is a real aspect of the teaching process that never seems to get discussed publicly.

-

16.

Older readers might remember the discussion around quality in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

-

17.

The danger of the Gove ideological flip-flop in favour of knowing lots of things is to lose the practice of creatively encouraging pupil engagement in their own learning. In the Jesuit tradition, we have always liked Ignatius’ wise observation in The Spiritual Exercises §2: ‘For it is not much knowledge that fills and satisfies the soul, but the intimate understanding and relish of the truth’.

-

18.

I presented this proposal in a paper during the Network for Researchers in Catholic Education at DCU in October 2019 and received very positive feedback.

-

19.

Obviously, this may simply reflect three things that I happen to have noticed, you may want to point out a lot more things that have not occurred to me.

References

CES. (2012). Religious Education Curriculum Directory for Catholic schools and colleges in England and Wales. London: Department for Catholic Education and Formation of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales.

Ofsted. (2019). School Inspection Handbook at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-eif.

Towey, A., & Robinson, P. (2016). The New GCSE religious studies course for catholic schools AQA. Hampshire: Redemptorist Publications.

White J. (2018). The Weakness of Powerful Knowledge, In London Review of Education, July, 2018.

Whittle, S. (2019). Religious Education in Catholic schools: Contemporary challenges, In Contemporary Perspectives on Catholic Education Lydon J. (Ed.). Abingdon: Gracewing.

Young, M., & Lambert, D. (2014). Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice. London: Bloomsbury.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Moffatt SJ, J. (2021). Religious Education as a Discipline in the Knowledge-Rich Curriculum. In: Whittle, S. (eds) Irish and British Reflections on Catholic Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9188-4_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9188-4_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-9187-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-9188-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)