Abstract

The empirical evidences and reports by multilateral and bilateral organizations show that major proportion of total workforce is engaged in the informal sector such as agricultural sector, construction industry, home-based work, small-scale sector. India has experienced an enormous expansion of industrial production system, without pragmatic work conditions, such as lack of information and precautions against physical, chemical and biological injuries has resulted in high rate of prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases and illnesses. India is an emerging economy with around 92% workforce in the informal sector. The existing legal enforcement in the labour sector systemically excludes the workforce in the informal sector. This paper attempts to examine the situational analysis of occupational health status, levels of health hazards, living and working conditions, wage levels and safety of women workers in the informal sector in India. The specific research synthesis has been initiated to study the occupational hazards of women workers engaged in beedi rolling (indigenous form of smoked tobacco) and construction work in India. Further, this article focuses on critical review of existing legal provisions, policies and their enforcement status and also draws relevant suggestions to improve policy measures on health and safety guidelines of women workforce in informal sector in India. It is evident that women’s work remains underpaid, unrecognized and uncounted as household income. Undernourishment of women and infants, incidence of poor maternal and child health has been attributed to lack of adequate social security measures and welfare benefits (e.g. maternity leave) to female workers in Beedi rolling and construction work. Prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases—Respiratory, Dermatological, Muscula-skeletal diseases, heat stroke, dehydration, and psychological stress are high. Policy implications and recommendations from the study will serve as evidence for necessary labour law reforms and include informal sector and female workforce, considering their substantial contribution.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Informal economy

- Health hazards

- Gender discrimination

- Construction worker

- Beedi worker

- Economic exploitation

- Social security

Introduction

The empirical research and published reports by multilateral and bilateral organizations show that major proportion of total workforce (92%) is engaged in the informal economy such as agricultural sector, construction industry, home-based work, small-scale sector and traditional rural industries. This sector is owned by individuals or families or function as self-employed and is engaged in the production or sale of goods and services. In emerging economies particularly India, women workforce is most vulnerable to occupational diseases and illness. Post globalization, India has experienced an enormous expansion of industrial production system, unregulated legislation which has resulted in a high rate of prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases and illnesses. The present paper focuses on analytics of causes and consequences of health inequality, safety of women workers in informal sector in India. The systemic analysis initiated to study the occupational health hazards (magnitude and nature of injuries) and occupational vulnerability of women workers engaged in beedi (indigenous smoked tobacco also known as south Asian cigarette) rolling and construction work in India. Further, the article addresses the relevance of existing legal provisions, policies and their enforcement status and to draw relevant suggestions to improve policy measures on health and safety guidelines of women workers in informal sector in India.

Review of Methodology

Review protocols, data search strategy, design, data sources and population of the study:

An extensive literature and data search was undertaken using online search engines. The search was restricted to PubMed, JSTOR, EPW and Science Direct. Data was obtained from the Government of India reports including the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Office of Registrar General of India, Ministry of Statistics and Planning Implementation, Ministry of Labour and Employment, and Statistics of Factories. The author reviewed peer-reviewed articles published in reputed journals, relating to the subject of occupational health hazards of women workers in unorganized sector. The online search was made using keywords such as informal economy, workers health in unorganized sector, female work participation, occupational health and gender, health concerns of female workforce in informal sector. Additionally, used secondary data published by national family health survey, central bureau of health intelligence, union budget economic survey and annual reports, labour bureau and census reports. This study also included a descriptive cross-sectional analysis to understand the situational analysis of women workers in beedi rolling and construction work in India.

Results

Most of the total workforce (~92%) in India are engaged in the so-called ‘informal sector’ or unorganized sector of the economy that does not come under the purview of existing occupational laws (Tiwary and Gangopadhyay 2011). The informal sector workers are ‘those workers who have not been able to organize themselves in pursuit of their common interest due to certain constraints like casual nature of employment, ignorance, illiteracy, small and scattered size of establishments’ (GOI 1969). Further informal sector workers work in the informal sector enterprises which are owned by individuals or households that are not constituted as separate legal entities independent of their owners (Fig. 1).

According to GOI (2008), enterprises existing in the informal economy are defined as ‘all unincorporated private enterprises owned by an individual in households engage in the sale and production of goods and services operated on a proprietary or partnership basis and with less than ten workers’. India being an emerging economy with 91% workforce in the informal sector (GOI 2001; Paromita 2009). Neetha (2006) paper shows 362.08 million workers in the unorganized sector. They contribute more than 60% to national income (Tiwary et al. 2012; Paromita 2009). Inspite of their enormous contribution to the existing legal provision in the labour sector excludes the workforce in the informal sector. Therefore, it is important to protect their rights and entitlements by providing them with minimum wages, basic social security measures, infrastructural facilities, improved regulatory mechanisms, and improved health and safety measures. The importance of employment accessed by women in terms of gender discrimination is noticeable. Major proportions are engaged in low productivity, low income and insecure jobs on farms in the unorganized and informal sectors (Institute for Human Development 2014).

It is evident from Table 1 that 90.87% of the overall workforces are in the unorganized sector in which around 94.67% are women workers, even in the organized sector 58% of the workforce engaged is in informal nature of employment. Further, there is an increasing trend in the informal workforce in India from 92% in 1983 to 93% in 2000 (Sakthivel and Joddar 2006). It is evident that the organized sector is only 9.10%, ironically, the existing law focuses only on this minor population of the organized sector. As in the case with the non-farm workforce that around 80% is on the informal sector. Even in the unorganized workers Social Security Act 2008 does not cover sufficiently the women workforce. Further, it does not stipulate Social Security measures, for instance, minimum wages, decent working conditions, equal pay and protection against sexual harassment at the workplace. It reflects the minimum role of the state in provision of social welfare services to the women workforce in the informal sector. In the past three decades, both the industrialized and emerging economies have undergone significant paradigm shift in industrial production system. The twenty-first century has witnessed not only large-scale expansion of informal economic system but also has resulted in high rate of global burden of diseases including communicable and non-communicable diseases. Tables 2 and 3 shows the informal sector provides large-scale employment and livelihood opportunity to majority of population in India.

The analyzed data reveals work-related injuries, diseases and illness of female workforce in the informal sector in India (see Table 4). They were exposed to various forms of exploitations, discriminations and occupational health hazards. Most importantly, female workers are working in unhealthy environment, unsafe working conditions and dual burden of work including household work.

Majority of women workforce are in the agriculture (87%), which is the most hazardous sector. The agricultural hazards (GOI 2001) are classified as farm machinery (tractors, threshers, fodder, chopping machines), agriculture tools and implements (pick, axe, spade and sickle), chemical agents (pesticides, fertilizers, strong weed killers), climate agents (high temperature, heavy rain, humidity, high velocity wind/storm, lightening), electricity, animal/snake bites and other agents such as dust, solar radiation and psychological stress due to socio-economic problems. The published data is an underestimation of non-fatal injuries, burden of diseases and mortality rates. 70–76% of the women work as heavy manual labour for less wages has resulted in higher prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases particularly respiratory, dermatological, Musculoskeletal, heat stroke, dehydration, psychological stress, etc. Moreover, these employments instead of relieving them of poverty further aggravates vicious cycle of poverty and ill-health continues. It is evident that women who work remain unpaid, underpaid and also unrecognized and uncounted as part of household income, not protected under legal and regulatory framework, and they are subjected to dual burden and to various forms of discrimination at work. The following Table 4 provides empirical evidences of health and safety of women workers in beedi rolling and construction work in India.

The key findings summarized below are derived from the empirical evidence:

-

a.

91% of the total workforce and 95% of the female workforce in India are employed in the informal economy and characterized by lower earnings with no upward mobility.

-

b.

The Factories Act of 1948 is applicable only to 8% of the workforce in the organized sector. Even the Unorganized Sector Social Security Act of 2008 does not adequately cover women workers.

-

c.

There is scant investigation related to injury and accidents.

-

d.

It is evident that women work remain unpaid or underpaid, unrecognized, uncounted as part of household income and also large-scale involvement of unpaid family members including children in beedi rolling.

-

e.

The undernourishment of women and infants, incidence of poor maternal and child health has been attributed to the lack of adequate social security measures and welfare benefits (e.g. maternity leave) to the female workers in informal sector.

-

f.

Among the female workforce, there is higher prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases particularly respiratory, dermatological, musculoskeletal, heat stroke, dehydration, psychological stress.

-

g.

There is large-scale involvement of economically and socially vulnerable population in informal economy. Majority of the informal sector women workers live in slum areas, availability of lack of primary and essential health and social welfare facilities including housing, water supply, sanitation, etc.

-

h.

Low wages pushes women workforce into absolute poverty and underemployment. Moreover, their social, economic, health conditions, standard of living before and after the beedi rolling and construction work remains same.

-

i.

Widespread illiteracy and poor health and low educational status among the women workforce is observed.

-

j.

Absence of adequate safety nets to meet contingencies towards ill-health, accident, death and old age.

-

k.

Women in the informal sector work longer hours than men.

-

l.

Women are forced to work under large-scale unsafe and unhealthy environment, thus being exposed to several occupational hazards.

-

m.

Children are exposed to all the hazards of tobacco, cement and construction materials, harsh climates and other associated occupational hazards as their parents.

-

n.

The workers are provided with limited access to medical care and social security facilities.

-

o.

A large number of women workforce are exposed to economic, sexual and health exploitations.

-

p.

The informal sector workers work odd hours, are forced to migrate to find their livelihood in unhygienic conditions; have no fixed employment; non-payment and no fixed minimum wages and subjected to over crowdedness and poor sanitary conditions.

-

q.

Lack of institutional mechanisms to deal with the informal sector.

-

r.

Lack of supply of personal protective equipments and injury prevention.

-

s.

Lack of/no training in occupational health safety and injury prevention.

-

t.

No regulation over the contractors, sub-contractors and sub-sub-contractors in the informal sector.

-

u.

Lack of political will and inadequate public policy support to the women workers in informal sector.

Discussion

The construction industry provides direct employment to at least 30 million workers in India (Chen and WIEGO Network 2007) which is considered the backbone of the economy. The interface between informal and formal sector in the construction industry is least understood, while the involvement of contractors and sub-contractor create further complications. The commendable contribution of this industrial segment in infrastructural development in India is highly appreciated enticing a great magnitude of workers who are unskilled or semi-skilled. Employment in the construction industry increased from 14.6 million in 1995 to more than twice in 2005, implying that 31.46 million workers (approximately 93% of the total employment in the construction sector) accounted to workers community in 2005 (GOI 2008). This booming construction industry represents 44% of all the unorganized urban workers in India (Tiwary and Gaganopadhyay 2011).

India is recognized as a global production base for beedi and cigarette and the second largest agro-factory base industry which is considered a major hub for beedi while the nature of work is labour-intensive (Joshi et al. 2003). In both construction and beedi rolling industry, majority of the workers are landless labourers characterized by poor socio-economic strata. Hardship and exploitation of women workers in these two subdivisions (i.e. Beedi rolling and construction) of informal sector are indicated (Yasmin et al. 2010). The hours count at worksite, for women are more than men, regardless of the government of India specification which is ignored by the owners as well as contractors. The occupational division of labour is related to different forms of exploitation (Tripathy 1996) in which women face the dual burden of discrimination, with restricted employment opportunities. Moreover, pursuing a career of choice is a problem among women (Singh and Gupta 2011). Certainly more cost is incurred in the case of women workers whose work depends on support from family or neighbours not taking care of their children back home (Bertulfo 2011). Due to this, they bring their children to workplace while in Beedi rolling, and also women as well as children are involved together to achieve production target due to time constraints.

Infrastructural facilities indicate poor ventilation, improper arrangement for clean drinking water and toilet facility particularly separate toilet facility for women. Highly unhygienic working conditions and proximity of space and dim lights were also observed. The spread of communicable disease on account of sub-standard work conditions like poor sanitary facilities are also serious concerns. The working environment includes exposure to vibrations, climate influences, noise and dust. Approximately 90% workers develop pain in various body parts, such as muscular-skeletal disorders, arthritis and rheumatism, cramps of finger, shoulder, cervical-back pain, lower abdomen pain, anaemia and vision problems, thinning of finger skin, fractures, noise-induced hearing loss, discolouring and tanning of skin and mucous membrane, cuts and wounds (Yasmin et al. 2010; Srinivasulu 1997).Women suffer miscarriage and complications in pregnancy and respiratory problems (Bhisey et al. 1999).

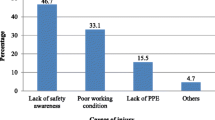

Silicosis, carbon monoxide, benzene poisoning and cytogenetic toxicity due to the exposure of dust particles is an additional silent killer (ILO 2011). Also, the vulnerability is increased in these segments to lumbosacral pain, peptic ulcer, haemorrhoids, diarrheal infection, congestion burning sensation in the throat, nausea and poisoning. Additionally, most of the accidents occur due to ignorance in following standard operating practices. High fatal injuries are identified by ILO in the construction industry (ILO 2011).

There is higher percentage of incidences in construction industry compared with the manufacturing sector in India (Jain 2007). It is estimated that of 17% of global work-related fatalities are noticed in this segment. Besides occurrence of injury in the work site area more are reported in case of women (Madhok 2005). Furthermore environmental conditions due to exposure to contagious and non-contagious diseases and illness also play major role. Approximately 4,03,000 people die in India due to occupational diseases and illnesses (ILO 2003). Poor socio-economic statuses are the other challenges that make them vulnerable towards malnutrition and anaemia. Absence of adequate safety nets to meet ill-health, accidents, death as well as old age brings them closer to deprivation and poverty.

Ignorance and negligence by the owners and contractors with respect to the Government welfare provisions on protective and promotional measures are evident. Frequent alteration of the contract system, regulation and work environment add further difficulties. The availability of safety surveillance is absent from the grass root level. Moreover the absence of grievance and redressal mechanisms are absent. The outsourcing by contractors and sub-contractors has led to profound negative impact in terms of diminishing job security. The contributions of manufacturer as well as of government are not seen in the monetary compensation to workers. No attempts have been undertaken by industrial management boards to provide post-delivery care to women workers. Now the question arises what could be done hence forth to avoid these occupation safety breach and health hazard. In this context, ILO (2011) has developed a graph known as ‘cycle of neglect’ which emphasizes on the negligence as the prime cause of occupational health and safety hazard and defines the condition of occupation safety and health. The findings of the study reveal lack of prioritization of occupational safety and health, lack of treatment including provision of first aid and referral services and compensation. Poor resource allocation for occupational health and safety on the improvement and collection of information are major causes as well as challenges for the government as depicted by ILO (2013). Further, it shows a lack of provision of social security measures, welfare benefits to the female workers in the informal sector that can combat undernourishment, incidence of poor maternal and child health.

In the construction industry, workers are vulnerable to workplace accidents, and occupational health problems. They are exposed to several hazards which are 4–5 times higher than that of manufacturing sector and exposed to various forms of occupation associated diseases including asbestosis, silicosis, lead poisoning, etc. In the beedi industry, about 90% of the workforce is working from home and majority of them are women workers. They are exposed to various raw tobacco hazards. More than half of the women workforce is in the age group of 21–35 years of age. There is no welfare and social security measures including maternity benefits for the women workers.

Several welfare funds have been established under the BOWS Act, CESS funds are collected for the welfare of the construction workers. There is also Beedi workers welfare fund Act of 1976, Limestone and dolomite workers welfare fund Act of 1972, Iron ore, manganese ore and chrome ore workers welfare fund Act of 1976, the Mica mines workers welfare fund Act of 1946, the Cine workers welfare fund Act of 1981 to specify the meeting of the expenditure in connection with welfare measure and facilities in health care, housing, education and recreation, etc. Despite the existence of several Acts, the welfare schemes are still not reaching the beneficiaries. The existing unorganized workers Social Security Act, 2008 is silent on the issues of women health. It has no specific provision for women workers such as equal remuneration, decent work condition, protection from sexual harassment at the workplace. The law does not abolish/control the existence of contractors and sub-contractors in the informal economy (Table 5).

It is evident from the data that women in informal sector are not protected under legal and regulatory framework. Moreover, the unpaid household work constitutes about 25–39% of national income. The legal enforcement has failed to protect the rights and entitlements of women workers and there is no investigation of injury and accidents, compensation, legal provisions. Furthermore, lack of availability of basic infrastructure facility including drinking water, toilet, washing and medical first aid facility at the workplace. Physical and chemical agents affect the female workers—especially antenatal (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC). Working conditions were simultaneously having a dramatic effect on the health of infants and family members. Evidence showed the absolute absence of trade union/associations to protect the rights and entitlements of women workforce.

Policy and Practice Implications of the Findings

There is greater need to recognize the significance of socio-economic and environmental determinants of women workers health in informal sectors in India. The findings from the study emphasize to, propose the significance of political will, in strict implementation of existing legislation. The Social Welfare Entitlements meant for them should be facilitated. Labour laws need to reform, including formulation of relevant new labour laws and amend the existing ones in the light of inclusion of informal sector and women workforce. To provide timely and adequate protective devices physically to prevent the accidents and further damage while at work. To provide access to essential infrastructural facilities including potable water, toilet (separate for women workers), lighting, etc. Regular provision of worksite inspection, risk assessment and public health surveillance is needed. We have to integrate the significance of interdisciplinary and trans-disciplinary approaches to understand women workers in informal sectors in India and prevent various risk factors including poor nutrition, infectious diseases, unsafe living and working conditions.

The government should prioritize to play active role of regulator to ensure social responsibility and recognize and count the contribution of women in economic activity. There is need to carryout interdisciplinary and also longitudinal studies to understand women’s health issues in informal economy. Further, there is need to generate reliable toxicological and epidemiological data on risks of occupational diseases for policy formulation and operational research in the fields of occupational health; formation of trade unions/affiliated associations to protect rights and entitlements of the women workers in the informal economy in India. Need for regular provision of worksite inspection, risk assessment and public health surveillance. Need to impart awareness education (health promotion) to the female workers regarding the occupational hazards and significance of using protective and preventive measures is highlighted.

-

1.

Contractors, manufacturers should ensure facilities like proper first aid kit, referral services to injured workers.

-

2.

Timely provision of drinking water, washing and bathing, separate latrines and urinals for women workers.

-

3.

Stability in employment status to improve their standard of living.

-

4.

Onsite strategic safety management and injury prevention.

-

5.

Regular worksite audit by labour welfare officers.

-

6.

To provide adequate social security measures particularly compulsory health insurance facility.

-

7.

To ensure networking of stakeholders (including government, private, non-profit and civil society organizations) participation in working with women workers in the informal sector.

-

8.

To create awareness and capacity development programmes of women’s rights and entitlements, wearing safety equipment.

-

9.

To ensure adequate minimum wages and maternity benefits.

-

10.

To establish strong employer and employee relation mechanisms.

-

11.

To create awareness about the availability and provisions of government schemes and free medical care facilities.

Conclusion

It is evident that the occupational health and safety (OHS) of workforce in the informal economy particularly the women workforce have been ignored. Further workers are constantly being exposed to new set of diseases and illnesses. The evidences direct to propose, that the occupational health service delivery system should undergo substantial paradigm shift with focus on various amendments and appropriate implementation of the legal provisions to provide compressive integrated healthcare to protect women’s health and safety. And legally imposing the accountability on stakeholders including employers, customers, labour unions, regulators, stake holders, the media, and the community in which they operate. In the existing legal provisions in India, the subject of occupational health, safety and entitlement of women workforce in the informal economy have been neglected.

India being the second largest emerging economy lacks constructive public policy, committed political will and ideological orientation towards fulfilling the occupational health, safety and infrastructural felt needs of the women worker’s in the informal economy. In the twenty-first century occupational diseases and illness in India amplify major problems in public health. Therefore, I propose application of holistic and interdisciplinary approach to understanding various dimensions of public policy to protect socio-economic, health rights, safety, welfare facilities and entitlements of women workers in India.

References

Barnes, T. (2014). Informal labour in urban India: Three cities, three journeys. London: Routledge.

Bertulfo, L. (2011). Women and the informal economy. A think piece. AusAID Office of Development Effectiveness.

Bhisey, R. A., Bagwe, A. N., Mahimkar, M. B., & Buch, S. C. (1999). Biological monitoring of bidi industry workers occupationally exposed to tobacco. Toxicology Letters, 108(2–3), 259–265.

Chen, M., & WIEGO Network. (2007). Skills, employability and social inclusion: Women in the construction industry. Harvard University, WIEGO Network.

Chen, M. A. (2007). Rethinking the informal economy: Linkages with the formal economy and the formal regulatory environment (Vol. 10, pp. 18–27). United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Dharmalingam, A. (1993). Female beedi workers in a South Indian village. Economic and Political Weekly, 1461–1468.

Government of India. (1969). Report of the national commission on labour, ministry of labour and employment and rehabilitation. New Delhi: Government of India. Retrieved from https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/sites/casi.sas.upenn.edu/files/iit/National%20Commission%20on%20Labour%20Report.pdf.

Government of India. (2001). Occupational safety and health for the tenth five year plan (2002–2007). TFYP working group Sr. No. 47/2001. New Delhi: Planning Commission, Government of India. Retrieved from http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp/wg_occup.pdf.

Government of India. (2008). Eleventh fifth year plan, 2007–2012: Agriculture rural development industry, services and physical infrastructure. New Delhi: Planning Commission, Government of India. Retrieved from http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/11th/11_v3/11th_vol3.pdf.

Government of India. (2012a). National policy on safety, health and environment at work place, ministry of labour and employment. New Delhi: Government of India. Retrieved June 25, 2013, from http://labour.nic.in/content/innerpage/environment-at-work-place.php.

Government of India. (2012b). Report of the working group on ‘labour laws and other regulations for the 12th five year plan (2012–2017)’ (Z-20025/9/2011-Coord). New Delhi: Ministry of Labour And Employment, Government of India. Retrieved, from http://planningcommission.gov.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp12/wg_labour_laws.pdf.

Government of India. (2012c). Statistical year book, India 2012. New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. Retrieved June 25, 2013, from http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/statistical_year_book_2012/htm/ch32.html.

Institute for Human Development. (2014). India labour and employment report 2014: Workers in the ear of globalization. Institute for Human Development and Academic Foundation: New Delhi.

International Labour Organisation. (2003). ILO standards-related activities in the area of occupational safety and health: An in-depth study for discussion with a view to elaboration of a plan of action for such activities. International labour conference. Report, 6(6), Geneva. Retrieved, from http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc91/pdf/rep-vi.pdf.

International Labour Organisation. (2011). Introductory report: Global trends and challenges on occupational safety and health. XIX world congress on safety and health at work, September 11–15, 2011, Istanbul, Turkey. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Retrieved, from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_162662.pdf.

International Labour Organisation. (2013). Safety and health at work: Hope and challenges in development cooperation. (EU-ILO Joint Project) “Improving safety and health at work through a decent work agenda”, (Geneva). Retrieved, from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/publication/wcms_215307.pdf.

Jain, S. K. (2007). Meeting the challenges in industrial safety management in construction works. Mumbai: Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited Anushaktinagar. Retrieved, from http://www.npcil.nic.in/pdf/Endowment%20lecture%20by%20CMD-1.pdf.

Joshi, K. P., Robins, M., Parashramlu, V., & Mallikarjunaih, K. M. (2003). An epidemiological study of occupational health hazards among bidi workers of Amarchinta, Andhra Pradesh. Journal of Academic Industrial Research, 1(19), 561–564.

Kalyani, K. S., Singh, K. D., & Naidu, S. K. (2008). Occupational health hazards of farm women in tobacco cultivation. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 8(1), 9–12.

Madhok, S. (2005). Report on the status of women workers in the construction industry. National Commission for Women.

Neetha, N. (2006). ‘Invisibility’ continues? Social security and unpaid women workers. Economic and Political Weekly, 12, 3497–3499.

Paromita, G. (2009). A critique of the unorganized workers social security act. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(11), 26–34.

Pingle, S. (2012). Occupational safety and health in India: Now and the future. Industrial Health, 50(3), 167–171.

Ramachandran, G., & Sigamani, P. (2014). Occupational health and safety in India: The need for reform. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(47), 26–28.

Saha, A., Nag, A., & Nag, P. K. (2006). Occupational injury proneness in Indian women: A survey in fish processing industries. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 1(1), 23.

Saiyed, H. N., & Tiwari, R. R. (2004). Occupational health research in India. Industrial Health, 42(2), 141–148.

Sakthivel, S., & Joddar, P. (2006). Unorganised sector workforce in India: Trends, patterns and social security coverage. Economic and Political Weekly, 2107–2114.

Sanghmitra, S. A., & Reddy, S. (2013). Migrant women workers in construction and domestic spaces in Delhi metropolitan area: An analytical study of empowerment and challenges. New Delhi: SATAT (unpublished report).

Saravanan, V. (2002). Women’s employment and reduction of child labour: Beedi workers in rural Tamil Nadu. Economic and Political Weekly, 5205–5214.

Singh, T., & Gupta, A. (2011). Women working in informal sector in India: A saga of lopsided utilization of human capital. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 4, 534–538.

Srinivasulu, K. (1997). Impact of liberalisation on beedi workers. Economic and Political Weekly, 515–517.

Tiwary, G., & Gangopadhyay, P. K. (2011). A review on the occupational health and social security of unorganized workers in the construction industry. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 15(1), 18.

Tiwary, G., Gangopadhyay, P. K., Biswas, S., Nayak, K., Chatterjee, M. K., Chakraborty, D., et al. (2012). Socio-economic status of workers of building construction industry. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 16(2), 66.

Tripathy, S. N. (Ed.). (1996). Unorganised women labour in India. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House.

Yasmin, S., Afroz, B., Hyat, B., & D’Souza, D. (2010). Occupational health hazards in women beedi rollers in Bihar, India. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 85(1), 87–91.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Indian Council of Social Science Research (MHRD), New Delhi though RPR F. No. 02/233/SC/2014-15/ICSSR/RPR entitled ‘Health and Safety of Women Workers in Informal Sector in India—A Study on Beedi Rolling (Tamil Nadu) and Construction Work (New Delhi)’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Panneer, S. (2019). Health and Safety of Women Workers in Informal Sector: Evidences from Construction and Beedi Rolling Works in India. In: Panneer, S., Acharya, S., Sivakami, N. (eds) Health, Safety and Well-Being of Workers in the Informal Sector in India. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8421-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8421-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-8420-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-8421-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)