Abstract

Displacement and resettlement of the human population due to the construction of large dams affect the physical and social conditions of the displaced families. The resultant resettlement process modifies the occupational patterns and the nature of health-related problems and, in turn, quality of life at the household level. Post-independence era in India has been earmarked for over all development through the construction of large dams to meet multiple purposes, however, such project has sometimes been opposed by several quarters on various grounds. One of the important criticisms against big dams is its effect on the quality of life of the displaced population. The present paper examines the quality of life among the Bhil and related tribes, which have been displaced by the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam on River Narmada in the western part of India. The socio-economic conditions of this tribe after resettlement have taken a turn towards realignment through redistribution of land and division of labour. As the size of land holding given to the displaced tribal population has decreased, there is a shift in their occupation from cultivation to agricultural labour. Animal rearing as a source of livelihood has declined drastically except in poultry farming and people have also adopted diverse occupations in non-agricultural fields for their survival. The consumption of food among the resettled families has decreased after resettlement leading to poor health conditions as a result of which occurrence of diseases has increased in spite of increased availability of modern health facilities. Attitude towards health-seeking behaviour has also undergone a significant change, wherein the tribal families which earlier believed in black magic/witchcraft/necromancy and herbal medicine have shifted to treatment through allopathic medicines.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In recent years, considerable stress has been laid on ‘The Quality of Life’ as a human development index in understanding the impact of socio-economic welfare schemes undertaken by Governments for people. The quality of life can be assessed by analysing living conditions of the people such as the standard of living, the level of their living, and the living style of the people. It can be inquired objectively by generating a list of information containing economic activities, social conditions and living environment of the people. United Nations defines quality of life in terms of human well-being, which is determined by factors such as socio-economic conditions of the population and their healthcare practices, etc. Post-independence era in India has seen over all development in nearly every walk of life. Massive projects have been initiated to develop agriculture, industry, road network, education, health care, urban planning, science and technology, etc. Construction of large dams on several major rivers of India has been found to be necessary for multi-purpose projects of development covering irrigation and generation of hydroelectricity (GOI 1985). Some of such important projects are creation of ‘Damodar Valley Corporation’ to manage the course of river Damodar, construction of ‘Bhakra Dam’ on Sutlej river in Himachal Pradesh, mainly for hydroelectricity, Sardar Sarovar Dam over river ‘Narmada’ in Gujarat, etc. Constructions of big dams, however, are opposed by several quarters on various grounds. It is argued that the main beneficiaries from the construction of these big dams are the big industrialists and farmers and not much attention is paid to the loss of the displaced tribal population which is already marginalized and is not able to take its case to the authorities in any convincing way. One of the important criticisms against these big dams is its effect on the quality of life of the displaced population (Amte 1989; Cernea 1985, 1994; Mathur and Cernea 1995; Mathur and Marsden 1998; Paranjpye 1990; Ramaiah 1998). Shah (2003) has examined the impact of resettlement on the quality of life of second-generation. The present paper examines the effect of the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam in the western part of India on the quality of life among Bhils and related tribes, which have been displaced by the construction in terms of economic activities and social conditions such as health and food habits.

The research on quality of life has recently acquired momentum, especially after the development of the UN Human Development Index (HDI). While critical attention was paid to it only during 1970s, soon it became the main focus of welfare of human beings globally (Mukherjee 1989). Quality of life is determined by a combination of several social and economic characteristics related to the life of the people of the area (Morse and Berger 1992; NBA; Sangvai 2002; Alagh 1995). A good health enables an individual to lead socially and economically more productive and active life (Karve 1956). The state of good health and well-being of individuals is not a static phenomenon but undergoes a change through a continuing process that depends upon various causative factors such as socio-economic status, nutritional and food intake, educational level, community environment, technology and so on (Naik 1969).

There is no doubt that environment is one of the most important factors which controls the health of an individual or a community (Akhtar and Learmonth 1985). An amalgamation of both environmental and socio-economic factors (Asian Development Bank 1998; Dash 2009; Lobo and Kumar 2009; Singh 1990; Sharma 1986; CSS 1999; Goyal 1996; NCA 1995; Parasuraman 1998; TISS 1993) works as a catalyst for the health of an individual. For example, it is argued that both the physical and social health problems of individuals are rooted in poverty and development (Baviskar 1997; Roy 1999, 2000; Independent Review Team 1997; Thukral 1992; ICLD 1988). However, some of the health problems do not simply arise out of poverty. The developmental levels of the community are also instrumental in having manifold repercussions on the health of people (Colledge 1982).

Quality of life, related to health, measures the capacity of an individual to fight diseases (Good 1996) and enables physical and social conditions favourable to eat, drink and take care of personal hygiene (Eyles and Wood 1982). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines ‘health’ as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being. Here, well-being is mapped on the basis of level of health care. The status and level of health care relates to the assessment of treatment and expenditure on curing the diseases of the patient. Hence, the present chapter discusses the quality of life of the displaced tribal people using the socio-economic variables including occupation, living conditions in terms of healthcare practices and food consumption.

2 Research Problem

The main objective is to discuss the impact of resettlement on quality of life of the affected tribal communities. The resettlement process has affected the quality of life in general and the levels of living of the tribal population in particular. Therefore, the quality of life in terms of socio-economic conditions and living environment including healthcare measures is needed to be analysed among the tribal population in the state of Gujarat. The state of Gujarat was selected for the case study as a larger part of Gujarat was submerged due to the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on river Narmada as a result of which it has the largest number of resettlement sites.

3 The Study Area

Due to the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam, the resettlement sites are developed in various geographical regions of Gujarat. The Government of Gujarat provided an option to the affected families of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra to resettle in Gujarat. The Sardar Sarovar Punarvasahat Agency (SSPA) eventually developed 235 sites in Gujarat to resettle the affected families opting to resettle in Gujarat from all three riparian states. Out of these, ten sites representing different physiographic features have been selected for the present study. Four sites are resettled by the displaced tribal people from the states of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat and the remaining two sites are resettled by the affected families from Maharashtra.

4 Methods and Materials

The construction of ‘Sardar Sarovar Dam’ in the area was an ambitious project of the government which covered three riparian states viz. Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat. It was considered that as Gujarat has the maximum share in the project, so it has the major responsibility to resettle and rehabilitate the maximum number of affected families in the state. As a result, the Gujarat government developed resettlement sites which are spread over seventeen physiographic divisions in seven districts in the state. On the basis of the physical setting of the region in Gujarat, four sites, i.e. Junarampura, Vyara-1, Vyara-2 and Pansoli from Vadodara Plain, three sites, i.e. Golagamdi, Parveta (MH) and Parveta (Guj) from Orsang-Heran Plain and Vejpur, Gora and Dhefa belonging to Mahi Plain, Narmada Gorge and Lower Narmada Valley have been selected. Using a stratified random sampling technique, the required information through structured questionnaire has been collected to examine the relevant dimensions of the study. A total of 330 households of Bhil tribe have been surveyed from the sample villages.

5 Results and Analysis

The economic condition of a family reflects their quality of living. It is controlled by the occupational pattern of the family. The section is broadly analysed into two parts, i.e. occupation and health in terms of dietary habits and diseases.

5.1 Occupational Patterns

Occupation is an important parameter to study the quality of life and economic potential of the subject. The displaced families in their original villages were living in close proximity to natural surroundings. Their economic activities were determined by ecological conditions which were integrated and self-sufficient for livelihood. These people were engaged in primary economic activities such as primitive farming, cattle rearing, fishing and hunting-gathering for subsistence. The agricultural labour in the form of parji (exchange of labour) system during peak seasons was common in the region. But after displacement, the percentage share of the tribal population engaged in performing these economic activities was affected by social ecology of the recipient areas and has been forced to do work beyond their customary occupations. Hence, it is important to understand changes in the work structure of the affected tribal population.

Depending upon the time devoted to each type of work, the main occupation of the tribal families has been carried out in the survey. Main occupation here refers to the economic activity in which a person works for the major part of the year. The occupation has been divided into six categories, i.e. cultivation, cattle rearing, agricultural labour, wage labour, service and others. The first three categories relate to cultivation and related activities whereas the last three belong to non-agricultural pursuits. The fishing, hunting, gathering and small business have been classified into ‘others’ category.

A majority of the tribal people are engaged in cultivation and related work. More than 80% of the families are engaged in cultivation in their native villages (Table 10.1). However, the size of the land holdings varies substantially among them. In the primitive tribal culture, the cultivation is characterized as a traditional system and is labour intensive. Nature plays a dominant role in determining the economic pursuits. Although the percentage share of population in this occupation has declined after resettlement, yet it still attracts more than 60% of the tribal households. This decline does not mean that cultivation is losing its popularity but can be explained in terms of a huge decrease in the land holdings. While the average land holding was more than fifteen acres (including Jangal khata land) per household at their native villages, the landholding has now been reduced to more than three times at resettlement sites. However, the number of households having agricultural land has increased due to the provisions made by Narmada Water Dispute Tribunal (NWDT) award. Another important transformation which has been noticed is that the cost of livelihood has increased significantly. So, the people are forced to engage in other occupations to meet out the increased expenditure.

Animal rearing was the second most popular occupation and source of livelihood at the native villages because people could manage to collect fodder for animals from the nearby forest and Gochar land. But at resettlement sites, they have lesser number of animals. Here, none of the resettlers has opted for animal rearing as main economic activity. Interestingly, the nature of domestication of animals has changed at resettlement sites. Here, poultry has become more popular whereas in the old villages goat-rearing was more prevalent.

The resettled families do not have an interest in cattle rearing because due to the reduced availability of common property resources, people have started nurturing poultry in the house courtyard. The number of bullocks, too, has fallen to a great extent because their use in agricultural fields has been reduced due to lack of terrain and now they have started using tractors for cultivation and transportation. The agricultural labour as a main occupation was not admired by the resettlers at their native places and less than 1% families opted for it as a main occupation. It was because of the prevalence of parji system in which labour was exchanged instead of hiring it. A drastic change in this category at the new sites can be observed and it has become the most important main occupation after cultivation.

Wage labour was not prevalent among the resettled families at their old villages. They were shy to go for other works except for agricultural labour because, in their minds, they were not too educated, trained or skilled to perform non-agricultural work. But at resettlement sites, the growing demand for money to meet out the household expenses has compelled them to go out for wage labour in nearby semi urban and urban areas. As a result, it has become the main occupation of 8% households. The population has mostly adopted works such as house construction (Kadiyakam), stone cutting, cotton ginning mill, etc. Some of them have started to drive tractors on rent to cultivate the land as well as use it for earth filling and transporting of stone, etc.

Though the economic gains in the activities like collection and selling of firewood from the forest were negligible in the submerged villages, it played an important role in providing employment to the tribal community. Hunting and fishing had been the basic and ancient occupations of the tribes. Due to their proximity to forests, they had access to the forest produce and river resources. In the modern times when cultivation and domestication of animals have been adopted by the tribal society, they have reduced their dependency on forest and river as a source of food and employment. Gathering was also one of the important forest-based activities, though it was not considered as the main occupation, yet a section of the resettled population still maintains this activity as their traditional occupation. In the old villages, people used to collect forest produce from the nearby areas. They did not carry out these activities at a commercial level and used them for fulfilling their daily requirements like collecting the firewood. Every household consumed a minimum of 5–8 kg of fuel wood per day.

During the lean agricultural period, the people often went out in the forests for gathering of woods, leaves, roots, fruits, etc. In this way, the forests provided a wide range of food items and adequate fuel and firewood. But the situation has radically changed at resettlement sites and this activity is no more popular due to the non-availability of forest land in the nearby areas. Some families are now engaged in household manufacturing works such as basket making, pottery making and have become artisans, ironsmiths, tailors, shopkeepers, vegetable vendors, ice cream vendors, etc. These activities have increased to about 0.9% at resettlement sites. A few of the households had been part of the service sector (in public or private sector) at their old villages, which has increased to more than 5% at new sites.

Thus, the above description of the economic activities of the tribal people indicates a high degree of self-reliance in the submerged villages under the largely non-monetized economy. Although there was no monetary savings by them, the existence of these complementary production sources effectively prevented the emergence of unemployment in their community. But after resettlement, resettled families have become more dependent on employment in the agricultural sector, as well as in the service sector to earn money for their livelihood.

5.2 Health and Quality of Life

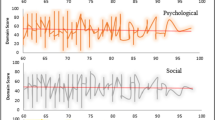

The problem of health may affect the body in two ways––at mental as well as at physical level. Though both types of health care are important, physical health is more important as it may lead to the mental problems if the physical health of a person is not good. It is observed that the different types of mental disturbances are faced by the tribal people. Most of the households suffer from demoralization followed by stress and anger.

Resettlement in the fragile environment consists of settling on the land that has been already extensively used or is not fit for cultivation and exerts immense mental and physical hardship on the tribal. Besides, people face financial difficulties as well and suffer from the availability of poor information system. After resettlement, the self-sustained system of food intake in the tribal world has been disrupted due to the loss of ancestral agricultural land, and as a result, they have to purchase food items from the market. The expenditure pattern indicates that it has increased after resettlement. It is observed that the tribals who shifted from Gujarat part of Narmada Valley spend more money on managing food as compared to the expenditure done by families of the other two states.

6 Change in the Dietary Habits

To see the change in the dietary habits, the frequency of taking meals in a day by the resettled families has been studied. It is interesting to note that more than 45% of the resettled families take meals thrice a day which has decreased at a rate of around 55% at their native villages. Thus, it can be concluded that the condition of resettlers has declined in terms of number of meals consumed in a day. About the quality of food, resettlers also seem to have compromised. The resettled people have reported that they have no choice other than to consume cheaper, poor quality food because the good crops are to be sold in the market. But, before resettlement, the situation was better. They used to adopt the rotation of various crops, and as a result, they had a choice of a wide variety of food.

The quality of food intake has also been greatly influenced in terms of the consumption of non-vegetarian food. Table 10.2 shows that the proportion of families consuming non-vegetarian food among the resettled families has decreased from 43% to 38% after resettlement.

In terms of the frequency of consumption of non-vegetarian food, the maximum number of families consumes non-vegetarian food once in a month followed by once in a week, i.e. 59% and 33% families respectively. However, a large number of the resettlers prepare meat and eggs at home by keeping fowls in house courtyards, whereas fish is bought from the market. It is important to note that the meat and fish, prominent sources of proteins are on the decline from the diet of resettled people. This is mainly because of the non-availability of these food items at affordable prices.

6.1 Disease and Health

Food consumption and status of health are two sides of the same coin of the health care. Hence, the status of health of the resettled population at resettlement sites has been studied. In the submerged areas of the tribal tract in Sardar Sarovar Project, the tribals used herbal medicine and traditional methods of magic, etc. But after resettlement, the Government and NGOs have provided modern healthcare facilities at the resettlement sites for their use. Centre for Social Studies (CSS) has pointed out that there are better levels of medical care in or near resettlement sites as compared to the submerged villages. However, Whitehead (1999) found that the government has taken little care in informing the resettlers about the local health problems and they are often served poorly.

The prevalence of different diseases among the resettled population has been given in Table 10.3. It is very surprising to note that the occurrence of different diseases per 10,000 population is found to be higher in case of fever, headache, kamdo (pain in limbs), malaria and stomach pain at resettlement site. However, the diseases such as cold, cough, skin etching and TB have decreased drastically. A large number of the people replied about their stomach problem due to indigestion of food. They used to consume coarse grains such as Bajra, Maize, Kodra, Bhadi and so on in their old villages. The course flour was prepared by grinding with Gharganti (rotary quern). But at resettlement sites, they have started consuming fine flour of wheat which is grinded by flour mills that causes indigestion problems.

Some people also face obesity problem due to declining physical work as a result of the change in the geographical area. Skin diseases have also been reported at their present sites, but it is on a drastic decline after migration. It has been reported that the incidences of fever and malaria are found higher at resettlement sites. It has been observed that vulnerability to illness has increased at resettlement sites.

In the present study, an enquiry about the sources of medical treatment of the sample families was made and results are given in Table 10.4. This table reveals that a number of families used different sources of medical treatment. In their old villages, resettled people took recourse to herbal treatment whereas at resettlement sites government has provided modern medical treatment facilities. The majority of the resettled families take treatment from private or charitable dispensaries and General Hospitals. It is important to note that among the resettled families the tradition of going to Badwa Badwa/Bhuaa (Quacks) has declined from 22.81% to only 14.29%. It is also interesting to note that most of them are not willing to go to Primary Health Centre and Community Health Centre due to non-availability of doctors there at the time of emergency. During the pre-resettlement period, most of the people of the resettled families used to take local or traditional medicines extracted from the forest produce. The ‘Bhuaas’ extracted these local medicines from leaves, woods, roots and barks of trees. After resettlement, this facility ceased to exist for them, while allopathic facilities have not been adequately extended to many of them even in the case of a serious illness. The study indicates that a decline in the use of traditional and home-based remedies is mainly because of social disruption, as a result of which most traditional medicine users have dispersed to other geographical regions. The governing reasons for it are non-availability of medicinal plants in the resettled villages and belief of the resettled people that the traditional medicine could not cure modern diseases along with changes in (age structure of the heads of the households) the role of decision-making process in the households which have affected most of the decisions regarding the type and place of treatment. Although the change was found to be positive in favour of modern methods of allopathic treatment, some families continue to resist the use of modern health facilities.

An investigation on the causes of resistance to modern health facilities was also carried out among the affected families. Table 10.5 demonstrates the responses of surveyed families about the causes for their lack of interest. There is a medical cell in SSPA at Vadodara that visits the resettlement sites on a regular basis accompanied by an MBBS doctor.

The findings suggest that the resettled population has yet to learn to make better use of healthcare facilities available in the area and biological adjustment to the changing environment will also take some time.

7 Conclusion

Construction of Sardar Sarovar dam on river Narmada in Gujarat has displaced large number of people in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh due to submerging of their villages. These displaced people have been given resettlement sites and governmental assistance to move to new places leaving their land, economy, history, culture and age-old memoires of their forefathers. This large scale displacement has created several social, economic and cultural problems. The resettlement plays a vital role in assessing the quality of life in terms of standard of living that has been calculated by taking into account variables such as expenditure on food and diseases, dietary change and change in occurrences of diseases at a new area.

The economic conditions have also been analysed by taking occupational patterns. A change in work force may occur after a sudden influx of population on land and availability of resources at resettlement sites. So, it is also important to find out the occupational structure. The results indicate that the self-sufficiency/dependency in terms of economic activities has lessened after resettlement. Although there was no saving at old villages, the existence of complementary production sources prevented the emergence of unemployment.

The results show that a majority of the resettled families before migration were engaged in agriculture and related activities (cultivation, cattle rearing and agriculture labour) and a few families were engaged in non-agricultural activities such as fishing, hunting, wage labour, service and small business. The dependence on cultivation has lessened after resettlement which was the most preferred main occupation among the resettled families. As the main occupation, the proportion of families engaged as agricultural labourers has increased and it has become the second most important economic activity at the resettlement sites. But a decreasing trend has also been observed in cultivation and cattle rearing, fishing and hunting, gathering from the forest and other common areas. The tribals did not find any favourable conditions at the resettlement sites to pursue these activities. Wage labour, too, became vital for sustenance and the percentage share engaged in service and small business has also increased. However, it is still very low at their resettlement sites. In the light of above one can say that instead of self-sufficiency, resettled families have shown more dependency on employment in the agricultural sector as well as in the service sector.

Cattle rearing was the most preferred professions supplementing agriculture by providing subsidiary benefits such as organic manure to the displaced at their native villages. This has been replaced by agricultural labour after resettlement. However, some of the resettled families have started poultry farming at new sites as it was found to be easier. Cattle rearing is on the decline due to the low level of availability of resources and CPR at resettlement sites.

In brief, the tribal population was engaged in several types of occupations in their natural habitat. The majority of families are engaged in cultivation before as well as after resettlement. However, the dependence on cultivation decreased after resettlement and the families started depending more on agricultural labour and wage labour. In wage labour, they are engaged in activities like masonry (Kadiayakam), digging of well, construction at roadsides and so on.

It has been observed from the study area that the resettled people face considerable psychological disturbances at the time of shifting to new sites and as a result, a large number of families suffered from demoralization followed by stress and anger. One of the direct impacts of the transition was seen on their health behaviour. Their expenditure on food, dietary habits, incidence of different diseases, attitude towards traditional and modern methods of medical treatment, all have undergone drastic changes. These changes are of a mixed type––some are on the bright side while others are discouraging.

It was observed that the highest number of resettled families used to take meals three times a day in their old villages. A good percentage of families also consumed food twice a day. But after resettlement, the percentage of families consuming food twice in a day has increased. Majority of the households consumed non-vegetarian food before migration, but the number of families consuming non-vegetarian food has declined after migration. In brief, it can be said that the consumption of food has decreased after resettlement with a further decline in consumption of non-vegetarian food.

The occurrence of diseases such as malaria, pain in limbs, and stomach pain (due to indigestion of food) among the tribals has increased after resettlement. It is pertinent to note that the prevalence of diseases like Asthma, Cancer and Diarrhoea was found in the resettlement area but was not reported from the submerged villages. Although the distance of health centre decreased as compared to pre-resettlement period, the incidents of occurrence of diseases have increased. Some people faced obesity problem due to decline in physical work as a result of change in the geographical area. Although skin diseases declined at their present sites, the incidences of fever, malaria and headache increased at resettlement sites which were low in the old villages.

In the old villages, tribals mostly used herbal treatment. It has been informed that although the government provides medicines to the resettled people, about half of the tribal families responded that the medical facilities are not extended to them. Some of these people, who believed in allopathic medicine, took medicines from private or charitable hospitals as well as general hospitals, while others go for Badwa, Bhuaa (Quacks) and Bhagat. The village-wise expenditure on medical treatment exhibits that while higher expenditure on health in some villages has been incurred due to their proneness to health hazards; in the others, the families spend more money on health due to economic prosperity. The incidence of occurrence of some of the diseases has become high and as a result, the quality of life in terms of food consumption and occurrences of diseases has deteriorated among the resettlers.

In nutshell, it can be concluded that due to change in factors such as the size of landholding, animal rearing practices, loss of traditional medicinal system, etc. the settlers have shown a considerable decline in terms of quality of life. It is visible in a decrease in intake of food as well as a change in the pattern and frequency of diseases. Due to the loss of their natural habitat to which the tribals were habituated and had an organic communication with it in terms of livelihood, pattern of life as well as physical conditioning, the downward trend in terms of health and happiness is quite visible in the resettled community. The material compensation in terms of an alien ecosystem which effectively uproots them from their moorings without any sustaining cultural and ecological ambience plays havoc with a native community which sustains itself on shared belief and natural system. Hence, the study reveals a change in quality of life among resettled people, with a pronounced propensity towards a decline in terms of food, health and satisfaction.

References

Akhtar, R., & Learmonth, A. T. A. (1985). Geographical aspects of health and diseases in India. Concept Publishing, New Delhi.

Alagh, Y. K. (1995). Economic dimensions of the Sardar Sarovar project. New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications.

Asian Development Bank. (1998). Handbook on resettlement: a guide to good practice. Manila: Philippines.

Amte, B. (1989). Cry the beloved Narmada. Anandwan: Maharogi Sewa Smiti.

Baviskar, A. (1997). In the Belly of the river: tribal conflict over development in the Narmada Valley. New Delhi: Oxford university Press.

Centre for Social Studies. (1999). Monitoring and evaluation of resettlement and rehabilitation programme for Sardar Sarovar Narmada Project: Composite M & E Reports 15 through 24, Surat.

Cernea, M. M. (1985). Involuntary resettlement: social research, policy and planning. In M. M. Cernea (Ed.), Putting people first: Sociological variables in rural development. Berkeley: Oxford University Press.

Cernea, M. M. (1994). Involuntary resettlement in development projects: policy guidelines in World Bank-Financed projects (Technical Paper no. 80): Word Bank.

Colledge, M. (1982). Economic cycles and health: Towards a sociological understanding of the impact of the recession on health and illness. Social Science Medicine, 16, 1919–1927.

Dash, N. R. (2009). Sardar Sarovar Dam: A case study of oustees in Gujarat, India. In Huhua Cao (Ed.), Ethnic minorities and regional development in Asia: realities and challenges. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Eyles, J., & Woods (1982). The social geography of medicine and health. London: Croom Helm.

Good, B. J. (1996). Mental health consequences of displacement. Economic and Political Weekly, 31(24), 1504–1508.

Government of India. (1985). Report on the committee on rehabilitation of displaced Tribals due to development projects. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs.

Goyal, S. (1996). Economic perspectives on resettlement and rehabilitation. Economic and Political Weekly, 31(24), 1461–1467.

Independent Review Team. (1997). Displacement and rehabilitation in Madhya Pradesh. In J. Drèze et al. (Eds.), The dams and the nation, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

International Commission on Large Dams. (1988). World register on Dams, Paris.

Karve, I. (1956). The Bhils of West Khandesh: A social and economic survey. Poona: Deccan College.

Lobo, L., & Kumar, S. (2009). Land acquisition, displacement and resettlement in Gujarat: 1947–2004. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Mathur, H. M., & Cernea, M. M. (1995). Development, displacement and resettlement: focus on Asian experiences. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Mathur, H. M., & Marsden, D. (Eds.). (1998). Development projects and impoverishment risk- resettling projects affected people in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Morse, B., & Berger, T. R. (1992). Sardar Sarovar project: independent review. World Bank: Washington D. C, USA.

Mukherjee, R. K. (1989). The quality of life: valuation in social research. New Delhi: Sage Publication.

Naik, T. B. (1969). Impact of education on the Bhils. New Delhi: Research Programmes Committee Planning Commission.

Narmada Bachao Andolan. (undated). Narmada: The struggle for life, against destruction. Chittaroopa Palit for Narmada Bachao Andolan, Baroda.

Narmada Control Authority. (1995). Master Plan for R & R, Indore.

Paranjpye, V. (1990). High Dams on the Narmada: A holistic analysis of the Valley projects. Delhi: INTACH.

Parasuraman, S. (1998). Socio-economic conditions of people displaced by Durgarpur steel plant. Man & Development, 20(2).

Ramaiah, S. (1998). Impact of involuntary resettlement on levels of living. In H. M. Mathur & D. Marsden (Eds.), Development projects and impoverishment risk- resettling projects affected people in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Roy, A. (1999). The greater common good. Outlook, 5(19), 54–72.

Roy, A. (2000). The cost of living. Frontline, 17(3).

Shah, D. C. (2003). Involuntary migration: evidence from Sardar Sarovar project. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Sangvai, S. (2002). Narmada displacement: continuing outrage. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(22), 2132–2134.

Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd. (undated). Sardar Sarovar project on river Narmada: meeting the challenges of development. Government of Gujarat, Gandhinagar.

Sharma, N. K. (1986). Large Dams-a necessary developmental choice. Bhagirath, 33, 55–64.

Singh, S. (1990). Evaluating large Dams in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 25(11), 561–574.

Thukral, E. G. (Ed.). (1992). Big Dams, displaced people: rivers of sorrow rivers of change. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Tata Institute of Social Sciences. (1993). Sardar Sarovar project: review of resettlement and rehabilitation in Maharashtra. Economic and Political Weekly, 28(33), 1705–1714.

Whitehead, J. (1999). Statistical concoctions and everyday lives: Queries from Gujarat resettlement sites. Economic and Political Weekly, 34(28), 1940–1947.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mahmood, A., Dalal, S. (2019). Resettlement and Quality of Life of the Bhil Tribe in Sardar Sarovar Dam Area, India. In: Sinha, B. (eds) Multidimensional Approach to Quality of Life Issues. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6958-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6958-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-6957-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-6958-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)