Abstract

Although much is written about the approach of larger companies towards their environmental responsibilities, there is much less concerning smaller companies. This gap in research is particularly apparent within micro-businesses. If the sustainability actions of a business are related to the perceived drivers and barriers of the leader, then this should be even more apparent in very small companies where the leader is closer to the firm. This paper contributes by investigating the current sustainability behaviours of UK-based micro-and small businesses, with a specific emphasis on the drivers and barriers of their environmental activity. In order to achieve this, an empirical, cross-sectional study was carried out using a mixed-methods approach in partnership with the UK-based Federation of Small Businesses (FSB). The results find a surprising number of eco-friendly activities carried out by micro-and small business with a strong desire for support to overcome resource and capability barriers.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Micro-and small business

- Eco-friendly behaviour

- Drivers and barriers

- Environmental engagement

- Environmental actions

1 Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the sustainable, environmental actions of UK-based micro- and small businesses and in particular their perceptions of the drivers and barriers to engagement. For the purposes of this paper, a micro-business is defined as a company who employs fewer than 10 people (Mitchell 2014) and a small business is a company who employs between 10 and 50 people (EUR-lex 2007). Micro-and small businesses account for 99.3% of all private sector businesses in the UK (DBIS 2015), with over 19 out of 20 businesses in the UK employing less than ten people (Young 2015).

Although each individual business is small, it is their collective impact that is significant with micro-and small firms contributing up to 70% of global pollution (Halberstadt and Johnson 2014; Johnson 2013; Hillary 2000). Additionally, the UK Environment Agency (2003) has estimated that micro-and small businesses account for around 60% of commercial waste and nearly 80% of pollution incidents. This makes the collective engagement of micro-and small businesses fundamental to any effort to reduce carbon emissions and improve resource use.

However, despite the collective need and importance of micro-and small businesses to the sustainability agenda, the majority of micro- and small business managers have yet to engage with eco-friendly activities (Johnson 2013: Revell and Blackburn 2007). This makes understanding how to support engagement a significant and legitimate imperative. While there is little research that focuses specifically on micro-and small business environmental behaviour (Bos-Brouwers 2010; Lee 2009), there is some evidence that micro- and small business owners would like to engage with improved environmental practices, yet lack the ability to do so. Certainly, Lobel (2015) found that 90% of micro- and small business managers would be more energy efficient if they could. This suggests there is a lack of knowledge about the pro-environmental behaviour of very small firms and a need to understand their perceptions of the drivers and barriers to engagement in order to support them with current and forthcoming sustainability challenges (Halberstadt and Johnson 2014; Johnson 2013; FSB 2007).

In order to address the apparent gap in understanding argued here, this paper reports on empirical research which was carried out in 2016 with the support of the East of England regional group of the UK-based Federation of Small Businesses (FSB). The FSB is the largest direct business membership organisation in the UK with over 210,000 members.

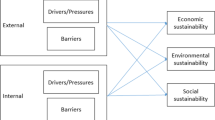

The research set out to analyse the drivers and barriers of pro-environmental behaviour in micro-and small businesses and to evaluate the environmentally pro-active actions taken by a sample of business owners. In addition, this paper will offer an assessment of what micro-and small businesses could be doing to improve their environmental sustainability and the support they may need to achieve this.

1.1 The Importance of Business Sustainability

While sustainability is increasingly a core business concern (Johnson 2013; Revell et al. 2010), it will never be fully accomplished unless all companies, especially the smallest, are involved (Hillary 2000). Pilot (2014) suggests the role of companies within the sustainability agenda is changing, with it becoming increasingly important for businesses to go beyond their core business activities to protect society and the environment. However, it is clear that companies of different sizes and competencies will react differently to the same environmental challenges and opportunities; with micro-and small businesses different from larger corporations in terms of their capabilities and resources (Parry 2012; Hammann et al. 2009; Biondi et al. 2000; Gerrans and Hutchinson 2000). This means that while smaller firms may be more agile, they may still take a reactive (rather than pro-active) approach towards sustainability and may experience the drivers and barriers to environmental engagement differently to medium and large companies.

However, the significance of sustainability specifically for micro-and small businesses is contested, with Samujh (2011), arguing that survival overpowers sustainability concerns for the majority of very small firms. In addition to Samujh (2011), Kloviene and Speziale (2015) also emphasise that in order for micro-and small businesses to contribute towards economic growth and stability, short-term survival issues will need to trump longer term considerations. This suggests that environmental actions may not bring micro-and small companies sufficient economic benefits, for example from resource cost savings or enhanced reputation, and that market intervention/network support maybe needed to facilitate such adoption and enhance the links between sustainability and enhanced survival rates (Samujh 2011; Kloviene and Speziale 2015).

1.2 Drivers and Barriers to Sustainable Behaviour

There are a number of drivers to pro-environmental engagement identified in the literature for small to medium (SMEs) and larger firms, with varying evidence linked specifically to micro-and small companies. In many cases, the literature does not specifically relate to these very small companies and the relevance is untested and assumed. This is significant because support to engage SMEs with the environment was initially based on what was known about the engagement of larger firms yet this proved to be inadequate or misleading (e.g. Spence 2007). Indeed, Bansal and Roth (2000) claim that drivers may vary in accordance to the business context, the business size and the situations that lead to their particular motivation. This may imply that micro-and small businesses are likely to encounter several barriers that prevent them from more fully engaging (Al Zaabi et al. 2013).

A number of drivers identified from within the literature as potentially relevant to micro-and small business will be discussed in the following sections, including personal ethical beliefs, cost savings, legislation/regulation and resource constraints.

1.3 Ethical Beliefs

Ethical and ecological beliefs have been identified as a major driver for sustainable actions (Williams and Schaefer 2013; Kehbila et al. 2009; FSB 2007). This was also demonstrated by Lobel (2015) who claimed that 70% of SME owners state that protecting the environment is highly important to them. However, Parry (2012) and Spence (2007) observed that although ethical motivations have attracted much attention from business researchers, it is not clear how this relates to very small companies where the owner is not considered to be an eco-preneur, or specifically setting up a ‘green’ business.

1.4 Cost Savings

Small businesses often have limited access to capital and limited cash flow, so it is understandable that cost savings may be identified as an important driver for sustainable actions (Lobel 2015; Pilot 2014). However, there is limited evidence that very small businesses make savings significant enough to warrant the investment in time and effort (Williams and Schaefer 2013; Fineman 2000), suggesting that cost savings may be part of a mix of motivations or less significant than for larger companies (Parry 2012). In addition, it has been observed that SME owners can believe that introducing environmental practices will initially cost money (Williams and Schaefer 2013; Revell and Blackburn 2007). Apart from the 2007 FSB survey (FSB 2007), that investigated social and environmental responsibility approaches by members, there is limited evidence that seeks to understand this conundrum from the perspective of the micro-or small business. Although the FSB survey (ibid) had a greater focus on social rather than environmental aspects and did not separate micro-and small from SME, the report did find that perceived cost, along with lack of time and lack of capacity, were barriers to small business engagement.

1.5 Legislation and Regulations

Blundel et al. (2011) argue that legislation to protect the environment has increased with Governments in different areas introducing policies to limit the damaging activity of organisations. As a result of this, micro-and small businesses in Europe and the UK at least, are all subject to at least some environmental compliance. However, SMEs have been known to comply through accident rather than design (Petts et al. 1998) and it is unclear how far micro-and small business are affected (directly or indirectly through the supply chain) or recognise compliance as a general motivation. Certainly, Al Zaabi et al. (2013) argue that legislation can be considered as both a driver and barrier, as compliance can reduce innovation in favour of meeting minimal requirements. Indeed Spence (2007) supported by Williams et al. (2017) argued that compliance limits engagement and acts as a glass ceiling: If compliance is the motivation, once compliance is fulfilled, no further action is required.

1.6 Resource Constraints

Verboven and Vanherck (2015) argued that most small businesses have considerable resource limitations that prevent them from integrating sustainable practices into their business as well as time constraints. It is also suggested that sustainability implementation costs can be relatively high (Butler, Henderson and Raiborn 2011) and that the majority of micro-and small businesses are hesitant to spend the money to become sustainable as it is not seen as a cost that can be transferrable to customers in terms of added value (Taylor et al. 2003). On the other hand, Condon (2004) argues that SMEs at least have an advantage when addressing ecological issues because their size enables them to respond more quickly to changes in the business environment in comparison to large and global organisations. It is not clear whether micro-and small businesses per se recognise or act on this agility.

1.7 Other Drivers

There have been many other drivers and barriers of sustainable activities that have been identified by business researchers but it is not clear how far these relate to micro-and small companies. For instance, it has been found that implementing environmentally and socially responsible practices can create competitive advantage (Matthews 2015; Miller 2010; Alzawawi 2014) but it is not clear how far this is achieved or perceived to be the case for micro-and small businesses—apart from those starting up as ‘green’ businesses. There is also a lack of knowledge relating to both consumer demand (Matthews 2015) and supply chain pressure as drivers for engagement by micro-and small businesses.

1.8 Literature Summary

While it is clear that sustainability is of growing concern for business (Pilot 2014; Johnson 2013; Parry 2012; Revell et al. 2010), it is not clear how far existing research on SME pro-environmental engagement relates to micro-and small businesses. Certainly a number of SME researchers suggest that more could be done to understand and support the smallest companies (e.g. Lobel 2015; Revell and Blackburn 2007) to take steps to reduce their collect environmental impacts. While a mix of motivations are recognised within SME research as potential drivers for business engagement, it is not clear how far these apply, or are perceived to apply, and to be experienced as benefits by micro-and small businesses.

1.9 Methodology

In order to analyse the drivers and barriers of pro-environmental behaviour in UK-based micro-and small businesses and to evaluate the eco-actions taken within such companies, an exploratory research approach was used. This allowed the primary researcher to understand the issues more thoroughly (Mirazee 2014) and to address ambiguity in a research area that was fairly new (Blumberg et al. 2011). In addition, a cross-sectional research design enabled the collection of data on several micro-and small businesses at a particular time so the research could be examined to detect patterns of association (Bryman and Bell 2011).

This research was conducted through a mixed-methods approach using both qualitative and quantitative techniques (White and Rayner 2014). Quantitative research was carried out through the use of online self-completion questionnaires and qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews. Validity and reliability were addressed through triangulation of methods and peer feedback.

1.10 Data Collection

For this research, simple random sampling (probability) was used as this is the only method of sampling without bias and was the most representative sample of the population involved in this research, due to the different sizes and natures of micro/small businesses (White and Rayner 2014).

White and Rayner (2014, p 65) define a questionnaire as “a series of questions, each one providing a number of alternative answers from which the respondents can choose.” Questionnaires generate data in a well organised fashion and the responses can then be measured, categorised and subjected to analysis so the researcher can understand the data collected (White and Rayner 2014). The use of a questionnaire enabled the researcher to ask participants about the sustainable activities implemented within their businesses, along with their reasons for undertaking such actions and what may prevent actions that are desired but not carried out. Participants had the opportunity to add additional comments under each question

The questionnaire was created online and promoted through social media. In addition, the primary researcher was particularly grateful for the support of the East of England Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) who distributed the questionnaire to micro-and small business members. A total of 65 responses were received allowing some generalisation of the quantitative findings. The East of England was chosen both out of convenience and due to the region being the driest and most low-lying area of the UK and particularly vulnerable to environmental change. The UK Climate Impacts Project (UKCIP 2003) expects the East of England to be affected by climate change through drought, heat waves, flooding and sea level rise with an increasing risk of physical damage from high winds. The region is also promoted as the ‘ideas region’ of the UK (EEDA 2011, p. 22) and as highly innovative in developing agile, creative solutions. The region is linked with the supply of UK energy via European gas pipelines from the North Sea; renewable energy from the UKs largest off shore wind farms in the North Sea and nuclear energy from Sizewell in Suffolk. Environmental issues specific to the region include congestion from a poor east-to-west transport infrastructure and high transport load to and from the container ports of Felixstowe and Harwich.

In addition to the questionnaire, five in-depth semi-structured interviews were carried out. These used a similar format to the questionnaire and enabled the primary researcher to explore the questionnaire results in greater depth by encouraging participants to expand on their answers. Indeed, both the questionnaire and the semi-structured interviews were divided into two sections. The first section asked questions about business, for example how long the business had been trading and the nature of the business; whereas section two focused solely on environmental engagement and asked the business owner about environmental behaviour, drivers and barriers.

As both the questionnaires and the interviews contained similar questions regarding the nature of the business, the relevance of sustainability, perceptions of the business as sustainable, drivers and barriers to sustainability and environmental actions undertaken, the data was analysed by taking an iterative case by case approach to each individual question. This enabled the researcher to explore answers in depth while reflecting on how widely ideas were found in the questionnaire.

2 Findings

2.1 Business Information

The first four questions were designed to understand more about the nature of the business. Of the 65 completed questionnaires, 83% were from small companies with between 10–50 employees and 17% were from micro-business with less than 10 employees. This indicates that the research collected is relevant to micro-and small businesses. In addition, all five of the semi-structured interviewees were from micro-businesses in order to add depth specifically to the most under-researched group. Of the respondents, nearly three out of four were the company owners from the initial start-up, meaning that environmental approaches introduced since start-up had been based on their actions. Additionally, the researcher asked the nature of the business so they were able to identify any connections between the activities they did and the type of business in question however there were over 33 different businesses questioned, a list of these business can be seen in Table 1.

2.2 Relevance of Eco-Friendliness to the Business

The aim of this question was to explore the owner’s initial position on the relevance of the environment to their business and how far they believed their business had the ability to be sustainable. Just over two-thirds (68%) of the questionnaire sample and all five of the interviewees, believed that being eco-friendly was relevant to their business and achievable for them. Example comments included:

The improvement in our environment and the strive towards a more sustainable lifestyle is relevant to all, particularly with increasing global pollution and the race of economic growth among nations (Design & project management, retail sector)

Yes although it is given that we are only a very small company it can prove difficult at times. I am aware of the availability of timber products that have been sourced from reliable/renewable sources through FSC and PEFC schemes and would ideally purchase materials bearing these trademark stamps. We would consider wherever possible the segregation of waste materials generated by our business (Shop fitting & Joinery Manufacturing).

Eco-friendly is relevant to all businesses, and yes, to ours too. Eco-friendly is not only beneficial to the environment but can provide cost savings to businesses too. (Event Production).

Nevertheless, this means that the remaining one-in-three questionnaire respondents did not believe that being eco-friendly was relevant to their business or believed they were unable to implement eco-friendly activities. Here comments emphasised the potentially contrary views highlighted in the literature regarding cost and cost benefit. This suggests that, similar to recent research on SMEs (Williams et al. 2017), the cost-based business case can be confusing and does not always stack up for smaller companies. For example:

There are environmentally friendly paints but they cost more and there is an environmentally alternative to white spirits but it doesn’t work. If it was possible to be more environmentally friendly I would be (Painter & Decorator).

Investing in LED lighting and solar panels would make us far more eco-friendly but we do not have the money to invest (Auto Electronics & Engine Tuning).

Nearly half of respondents (43%) considered their eco-friendliness as ‘average’ in comparison with other small firms. The remaining respondents were evenly divided between perceptions of their company as more or less eco-friendly than others. In the interviews, three out of the five interviewees rated their company as ‘average’ whereas the other two rated theirs ‘very’. The first comment points towards the complexity and confusion that small business owners can experience in trying to do the right thing and the need for actors to understand the different levels at which they can respond (Williams and Schaefer 2013). It is also clear that small businesses are restricted by the limitations of their business premises. These restrictions can come from the capital costs needed to make improvements but may also be from a lack of power to make changes with restrictions due to lack of (rented premises) and/or regulatory requirements. Comments from the interviewees included:

No one can win, because if we use computers then we are using an immense amount of electricity whereas if we use paper then we are killing trees. There is no absolute sustainable option to whatever we do and therefore we cannot win. Business C. Self-rated ‘Average’.

We try to be eco-friendly by recycling paper and that, using LED light bulbs, reducing electricity and water usage but we are based in an old listed building that we lease which has poor insulation and single glazing so we can’t really do a lot there. Business B, ‘very’.

I believe that we do as much as we possibly can to be sustainable and to reduce our environmental impact by implementing eco-friendly activities in all that we do. We make sure that all equipment is fully turned off when not in use and we do not print as many documents as we used to as all communication is now done through e-mail. Also, instead of travelling to conferences and meetings, we use Skype so that we are able to reduce emissions through travel. Business D, ‘very’.

2.3 Sustainable Eco-Friendly Actions Carried Out in the Business

This question was designed to explore the actions that respondents were already carrying out in their businesses which they considered to be eco-friendly and sustainable. Questionnaire respondents had a number of options to select from as well as the opportunity to add additional activities. Interviewees were encouraged to reflect in depth on their company behaviours.

Table 2 summarises the key questionnaire answers. It is clear from this that four actions are considered to be the most significant for micro-and small businesses—each reduced energy and resource use, were easy to implement, usually with no cost outlay and offered some potential cost savings. Williams and Schaefer (2013) similarly found that while SME managers can be critical of cost saving messages, the environmental actions carried out by them first did save money. However, cost savings were found to a by-product of actions not the motivation for undertaking them.

The four highest answers found in this current research were; ‘ensuring all equipment and lights are turned off when not in use’ (84.6%); ‘recycling’ (72.3%); ‘printing fewer documents’ (70.8%); and ‘communicating technologically’ (61.5%). However, it is clear that micro-and small business are involved with a surprisingly broad range of actions and this clearly indicates the potential for encouraging and supporting very small firms with stronger sustainability. Indeed, it was clear from the interviews that the infrastructure and support needs to be in place for these businesses to engage with environmental actions. For example:

We would like to do more to be more sustainable but because we are based in an old listed building with very little insulation, we need to have the heating on all the time to make sure it is warm so we are using a lot of electricity Business B.

The only reason that we make sure our lights are turned off is because it saves us money on bills, and then printing double-sided is because it saves money on paper and we only recycle because we have the bins available to do so Business E.

2.4 Drivers Towards Environmental Sustainability

Although the potential savings may be relatively small, ‘saving costs’ was seen to be the strongest motivator for initiating environmental behaviours, with 81.5% of questionnaire respondents selecting this option. Interestingly, ‘ethical/ecological beliefs’ was the second strongest motivator at 44.6% and ‘legislation and regulations’ was third with 38.5%. This suggests that the mix of motivations highlighted in the literature review is largely relevant to micro-and small businesses even though the research did not, in the main, focus on this group of very small businesses. It also supports recent work with SMEs (e.g. Williams et al. 2017; Cassells and Lewis 2011) that emphasises the importance of personal values in both how sustainability messages are received and how the mix of motivations is prioritised.

The interview responses were also quite reflective of the need to save money with each of the interviewees suggesting that ‘saving costs’ did encourage them to be more sustainable. However, interestingly, there was an emphasis on efficiency rather than saving cost to necessarily maximise profit. This suggests that respondents are trying to run the best business they can. For example:

I do what I do because it saves money and as a micro business, have little spare funds to be shedding out on bills etc. so I try to keep my costs to a minimum Business A

I would say that saving costs is the biggest driver for me because being such a small business, we do not have a lot of money to be spending out and therefore we try to reduce costs wherever possible Business C.

2.5 Barriers Towards Environmental Sustainability

While cost savings was perceived as a driver, the perception of ‘high initial costs’ was the biggest barrier (57%) for respondents to implementing sustainable activities. Additionally, ‘resource constraints’ at 52% was the second strongest barrier perhaps suggesting that respondents are not engaging in eco-friendlier activities because the business does not have the resources or capabilities to do so. A perceived ‘lack of support’ was highlighted by 30% of respondents. These findings were developed and supported through the interviews where Business C, in particular was passionate about the need for support:

There is a huge lack of support from the Government that helps micro and small businesses become eco-friendlier. If there were more Government funding/schemes available, then I would be more inclined to be sustainable as it would mean I would be able to do more to save costs, like install solar panels to reduce my electricity bills Business C.

The same need for support and for help with capital investment was also reflected in the questionnaire responses. For example:

My business produces a lot of wood waste as offcuts not suitable for use in projects. However, should funding or carbon grants become available again, I would invest in a furnace to burn all non-usable cut offs to heat the workshop rather than using diesel heating (Joinery & Manufacturer).

We would like to invest more in using recycled materials but the cost of these are too high at the moment (General Shop Fit & Maintenance).

The perceived barriers become particularly significant when the proportion of business owners who aspired to be more engaged with sustainability is considered. Indeed, 78% of the respondents said they would like to become eco-friendlier but the perception of, largely, cost prevented them. If the perception of cost is greater than the actual costs involved, then it is a lack of knowledge (what to do/how to manage) and support that is can be implied to be key. The remaining 22% who did not aspire to become eco-friendlier believed they were already doing as much as they could. However, if ‘business’, as a social actor, is to fully embrace sustainability and move beyond quick wins and cost savings, then there needs to be greater understanding of what very small businesses can achieve. There was some suggestion that the supply chain could play a greater role in facilitating such aspirations. The revised international environmental management standard ISO14001:2015 encourages engagement with tier 2 and tier 3 suppliers (as well as immediate suppliers and customers) and this may, in time, encourage greater innovation and support to micro- and small businesses.

3 Discussion

3.1 The Drivers and Barriers of Being Engaging with Sustainability for Micro- and Small Businesses

The results of the empirical research reported in this paper posit the prime motivator of sustainable activity as ‘saving costs’ and the second biggest driving factor is ‘ethical/ecological beliefs’. However, it is unclear how different motivations are perceived as inter-related to each other and this research did not fully explore what was meant by ethical/ecological beliefs. Certainly, a number of authors have recently emphasised the importance of ethical beliefs within SMEs (e.g., Williams and Schaefer 2013; Kehbila et al. 2009; Lobel 2015) and how cost savings are achieved as a by-product of actions made for other reasons. This is slightly contradictory to the findings from this current research and points towards a need to explore the ethical beliefs of micro- and small business owners with regards to sustainability in more depth. It is also possible that the greater emphasis on cost savings found in this research supports the survival over sustainability argument of Samujh (2011) and Kloviene and Speziale (2015) for unlike the traditional business case of ‘save money, save the planet’ (Revell 2003), very small businesses need to maximise any opportunity for efficiency in order to survive. Certainly, Parry (2012) argued that micro- and small business owners would only implement sustainable activities if they could see definite benefits of doing so.

It is an apparent contradiction that ‘saving costs’ can be seen as an important driver towards eco-friendlier behaviours yet, ‘high initial cost’ can also be perceived as the most significant barrier. This emphasises again that the perception of cost and motivation is not as clear as some early SME writers suggested and may be more complex for micro- and small businesses as well. The contradiction may also reflect ‘saving cost’ as quick win, no initial outlay efficiency savings versus ‘high initial costs’ actions that go beyond these quick wins and do require some investment. This may therefore reflect the perception and aspirations of business owners and their definition of sustainability and warrants further investigation.

Previous research (e.g. Verboven and Vanherck 2015; Butler et al. 2011; FSB 2007) demonstrated the importance of resource and time constraints in small companies where the owner-manager often requires a very broad set of skills to fulfil a number of roles within the company. This was a finding supported by this current research in the context of environmental sustainability. Over half of micro- and small business owners said that they do not have the resources and competencies required to implement desired environmental improvements.

3.2 Evaluating the Sustainable Actions Taken by Micro- and Small Business Owners

The research found a surprisingly broad array of actions carried out by the micro- and small businesses questioned. However, many of the actions can be considered relatively simple and included ‘ensuring lights and equipment are turned off when not in use’, ‘recycling’ and ‘printing fewer documents’ along with ‘communicating technologically’. However, it was clear that respondents had the potential to go beyond simple actions with a small number beginning to introduce renewable energy sources and looking to reduce electricity and water usage. Additionally, the questionnaire results demonstrated that around half of the respondents had been implementing the sustainable activities over time and the other half had looked to be eco-friendly from the beginning. The existing literature does not provide detailed insight into the actions that micro- and small businesses carry out in order to be sustainable but instead tends to emphasise the importance of sustainability across all businesses and within every economy. Reflecting on the actions, as well as the drivers and barriers, of sustainability for micro- and small businesses is a therefore a clear contribution of this paper.

Interestingly while the majority of respondents in both the questionnaire and the interview had been sustainable from the beginning, it is worth noting that most had been trading for less than five years. This reinforces and potentially supports the suggestion that sustainability in micro- and small businesses is a current issue with new start-ups increasingly recognising sustainability as a growing concern and opportunity for all businesses (Johnson 2013; Revell et al. 2010).

4 Conclusion

While notions of sustainability within business are complex (Farley and Smith 2014; Johnston et al. 2007), it is clear that the concept is very firmly on the business agenda. However, there has been limited research exploring the experience of sustainability from the perspective of micro- and small businesses, and it is that gap which the current research has aimed to address. Environmental engagement is increasingly relevant to all businesses, in all industries (Williams et al. 2017; Johnson 2013; Revell et al. 2010) and this position has been supported by the micro- and small businesses in this research: Sustainability and eco-friendly aspirations are relevant to very small businesses. This is an important finding because while micro- and small businesses tend to have a limited individual environmental impact, their collective impact is significant (Halberstadt and Johnson 2014; Johnson 2013; Hillary 2000). Engaging this group with actions that reduce their environmental impact and improve their overall sustainability should be a key goal for business support.

While there are many different drivers and barriers to environmental engagement, it is clear that the individual perception of the different micro- and small business owners is important. This suggests that, in terms of engagement, ‘one size does not fit all’ (Williams et al. 2017) and social actors looking to engage with this business sector need to understand the particular nuances of the mix of motivations and, potentially, how that links with the values and motivations of the individual business owner (Williams et al. 2017). After all, each business is different and each business owner will have different characteristics and personalities that impact on what motivates them to become more sustainable (Bansal and Roth 2000). From both the interviews and the questionnaire used in this research, ‘saving costs’ and ‘ethical beliefs’ were found to be the strongest drivers. However it is not clear how different motivations weigh against each other within each business or indeed, fit with additional drivers, such as, supply chain compliance and legislation to form a whole picture. It was also clear from this research that some concepts, such as costs and legislation, can act as both a driver and a barrier and this goes to emphasise the importance of the individual as the unit of engagement.

It is important to emphasise that this research found that micro- and small businesses are already carrying out a number of eco-friendly actions. This supports the research into social and environmental responsibility carried out by the FSB nationally in 2007. However, the finding is still significant because current research still largely maintains that sustainability is of little interest to very small businesses, who need to focus on survival (Samujh 2011; Kloviene and Speziale 2015). It can however be suggested, based on the findings of this research, that micro- and small businesses are engaging with sustainability and in doing so, actually increase their chances of survival: this is because the eco-friendly actions reported by respondents helped to improve the overall efficiency and competitiveness of the business. Looking forward, social actors engaging micro- and small businesses with sustainability might look to explore sustainability in terms of organisational resilience and the potential threats and opportunities that might encourage a deeper, longer term and more strategic view of environmental issues.

It was clear from this research that micro- and small businesses need support to more fully engage with sustainability. A clear desire was demonstrated to engage with the agenda but explicit calls for ‘how to’ knowledge and support were made. At the micro- and small business level, it is clear that there is still market failure without drivers clear enough to encourage deep change. Certainly, the UK Labour Government during the 2000’s, with support from the European Union, invested heavily in support to engage SMEs with improved environmental performance. For example, the UK government invested £240 million between 2005 and 2008 under the Business Resource Efficiency and Waste Programme (BREW) to encourage businesses to voluntarily improve their environmental performance through resource efficiency (NAU 2010) and directed a proportion of Landfill Tax to encourage business in this way (£214 million 2008–10). Respondents to this current research were clear that if there was Government funding/funded support it would help them to overcome initial costs and resource constraints. Working together to develop and share best practice and overcome common issues, such as rented premises and access to renewable energy, would be likely to improve the survival and economic growth of these companies in the long term.

References

Al Zaabi, S., Al Dhaheri, N., & Diabat, A. (2013). Analysis of interaction between the barriers for the implementation of sustainable supply chain management. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 68, 895–905.

Allen, J. C., & Malin, S. (2008). Green entrepreneurship: a method for managing natural resources? Society and Natural Resources, 21(9), 828–844.

Alzawawi, M. (2014). Drivers and Obstacles for Creating Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Operations. Retrived March 20, 2016 from http://www.asee.org/documents/zones/zone1/2014/Student/PDFs/109.pdf.

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: a model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. The Economic Journal, 112(477), 32–53. Wiley. Retrieved April 30, 2016 from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-0297.00682/full.

Berman Brown, R. (2006). Doing Your Paper in Business and Management: The Reality of Researching and Writing. London: SAGE Publications.

Biondi, V., Frey, M., & Iraldo, F. (2000). Environmental management systems and SMEs. Greener Management International. 55–79. (Spring).

Blumberg, B. F., Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2011). Business research methods (3rd ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

Blundel, R., Monaghan, A., & Thomas, C. (2011). Evaluating the role of enterprise policies in purposive sustainability transitions: A case-based comparison. In: Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ISBE) 2011 Conference, 9th-10th November 2011. Sheffield, England. Retrieved April 20, 2016, from http://oro.open.ac.uk/29593/.

Bos-Brouwers, H. E. J. (2010). Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19, 417–435.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2011). Business Research Methods (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, J. B., Henderson, S. C., & Raiborn, C. (2011). Sustainability and the balanced scorecard: Integrating green measures into business reporting. Management Accounting Quarterly, 12(2), 1–10.

Cassells, S., & Lewis, K. (2011). SMEs and environmental responsibility: Do actions reflect attitudes? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18, 186–199.

Condon, L. (2004). ‘Sustainability and small to medium sized enterprises: How to engage them’. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 20(1), 57–67. Retrieved March 19, 2016, from http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=657961202092589;res=IELHSS.

Department for Business Innovation & Skills (DBIS). (2015). Business population estimates. Retrieved April 21, 2015, from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/467443/bpe_2015_statistical_release.pdf.

EEDA. (2011). Improving the economy of the East of England. Retrieved July 20, 2016, from https://www.uea.ac.uk/documents/3154295/0/Improving+the+Economy+of+the+East+of+England.pdf/76397d58-3053-4d8d-86bc-8d9d49b595ff.

Environment Agency. (2003). NetRegs SM-Environment. Retrieved April 13, 2016, from http://www.netregs.org.uk/pdf/sme_2003_uk_1409449.pdf.

Epstein, M. (2008). Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental, and economic impacts. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

EUR-Lex. (2007). Definitions of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Retrieved March 15, 2016, from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=URISERV%3An26026.

Farley, H., & Smith, Z. (2014). Sustainability: If it’s everything: Is it nothing?. New York: Routledge.

Fineman, S. (2000). The business of greening. London: Routledge.

FSB. (2007). Social and environmental responsibility and the small business owner. Federation of Small Businesses Survey.

Gallagher, K. (2013). Skills development for business and management students: Study and employability (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gerrans, P. A., & Hutchinson, W. E. (2000). Sustainable development and small and medium-sized enterprises: A long way to go. In R. Hillary (Ed.), Small and medium-sized enterprises and the environment: Business imperatives (pp. 75–81). Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Hammann, E. M., Habisch, A., & Pechlaner, H. (2009). Values that create value: Socially responsible business practice in SMEs, empirical evidence from German companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(1), 37–51.

Halberstadt, J., & Johnson, M. (2014). Sustainability management for start-ups and micro-enterprises: Development of sustainability quick-check and reporting scheme. In Proceedings of the 28th EnviroInfo 2014 Conference (pp. 17–24) Oldenburg, Germany. ISBN 978-3-8142-2317-9. Retrieved July 20, 2016, from http://oops.uni-oldenburg.de/1919/1/enviroinfo_2014_proceedings.pdf.

Hillary, R. (2000). Small and medium-sized enterprises and the environment. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Johnson, M. P. (2013). Sustainability management for small and medium-sized enterprises: Manager’s awareness and implementation of innovative tools. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22, 271–285.

Johnson, M. P., & Schaltegger, S. (2015). Two decades of sustainability management tools for SMEs: How far have we come? Journal of Small Business Management, 10(1), 1–10.

Johnston, P., Everard, M., Santollio, D., & Robert, K. H. (2007). Reclaiming the definition of sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 14, 60–66.

Kehbila, A. G., Ertel, J., & Brent, A. C. (2009). Strategic corporate environmental management within the South African automotive industry: motivations, benefits, hurdles. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16, 310–323.

Kloviene, L., & Speziale M. T. (2015). Is performance measurement systems going towards sustainability in SMEs? In 20th International Scientific Conference Economics and Management (vol. 213, pp. 328–333).

Lee, K. H. (2009). Why and how to adopt green-management into business organisations? The case study of Korean SMEs in manufacturing industry. Management Decision, 47(7), 1101–1121.

Lobel, B. (2015). How small businesses are being more energy efficient in their operations. Retrieved March 21, 2016, from http://www.smallbusiness.co.uk/starting-a-business/small-business-advice/2494911/how-small-businesses-are-being-more-energy-efficient-in-their-operations.thtml.

Mitchell, L. (2014). Budget 2014: What do small businesses really want? Retrieved March 23, 2016, from http://www.businesszone.co.uk/deep-dive/leadership/budget-2014-what-do-small-businesses-really-want.

Matthews, R. (2015). Why small businesses are engaging sustainability. Retrieved April 20, 2015, from http://globalwarmingisreal.com/2015/03/05/sustainable-business-small-business-engage-sustainability/.

Miller, J. (2010). Sustainability: Is it a good choice for small companies? Inquiries Journal, 2(10). Retrieved March 20, 2016, from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/295/2/sustainability-is-it-a-good-choice-for-small-companies.

Mirazee, A. (2014). Exploratory research: What is it? And 4 ways to implement it in your research! [Online]. Available at: http://fluidsurveys.com/university/exploratory-research-4-ways-implement-research.

NAU. (2010). Reducing the impact of business waste through the business resource efficiency and waste programme. National Audit Office, London. Retrieved July 20, 2015, from https://www.nao.org.uk/report/defra-reducing-the-impact-of-business-waste-through-the-business-resource-efficiency-and-waste-programme/.

Newton, J., & Freyfogle, E. (2005). Sustainability: A dissent. Conservation Biology, 19, 23–32.

Parry, S. (2012). Going green: the evolution of micro-business environmental practices. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(2), 220–237.

Paulraj, A. (2009). Environmental motivations: A classification scheme and its impact on environmental strategies and practices. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18, 453, 486.

Petts, J., Herd, A., & O’Heaocha, M. (1998). Environmental responsiveness, individuals and organizational learning: SME experience. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 41(6), 14–30.

Pilot, M. J. (2014). Driving Sustainability to Business Success: The DS Factor Management System Integration and Automation. Wiley. Retrieved April 18, 2015, from http://academlib.com/10411/business_finance/driving_sustainability_to_business_success.

Porter, M. E., & Van de Linde, C. (1995). Green and competitive. Harvard Business Review, 120–134. (September-October).

Revell, A., Stokes, D., & Chen, H. (2010). Small business and the environment: turning over a new leaf? Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(5), 273–288.

Revell, A., & Blackburn, R. (2007). The business case for sustainability? An examination of small firms in the UK’ s construction and restaurant sectors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(6), 404–420.

Revell, A. (2003). The ecological modernisation of small firms in the UK. Paper presented to the Business Strategy and Environment Conference, Leicester, September 16th 2003. Retrieved July 20, 2016, from http://www.psi.org.uk/ehb/docs/blackburn-ecologicalmodernisationofsmallfirmsintheuk-200309.pdf.

Samujh, H. R. (2011). Micro-businesses need support: Survival precedes sustainability. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 11(1), 15–28.

Spence, L. J. (2007). CSR and small business in a European policy context: the five “C”s of CSR and small business research agenda 2007. Business and Society Review, 112(4), 533–552.

Taylor, N., Barker, K., & Simpson, M. (2003). Achieving “sustainable business”; A study of perceptions of environmental best practices by SMEs in South Yorkshire. Environment and Planning C, 21(1), 89–105.

Thiele, L. (2013). Sustainability. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

UK Climate Impacts Project, (UKCIP). (2003). Living with climate change in the East of England stage 1 report: Guidance on spatial issue. Environmental Change Institute (ECI), University of Oxford. Retrieved July 20, 2016, from http://www.ukcip.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/PDFs/EoE_tech.pdf.

Verboven, H., & Vanherck, L. (2015). Sustainability as a management process for SMEs. Schwerpunktthema, 23(4), 241–249.

White, B., & Rayner, S. (2014). Paper Skills (2nd ed.). Hampshire: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Williams, S., Schaefer, A., & Blundel, R. (2017). Understanding value conflict to engage SME managers with business greening. In J. D. Rendtorff (Ed.), Perspectives on philosophy of management and business ethics, ethical economy (Vol. 51). Studies in Economic Ethics and Philosophy, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46973-7_6.

Williams, S., & Schaefer, A. (2013). Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Sustainability: Managers’ Values and Engagement with Environmental and Climate Change Issues. Business Strategy and the Environment, 22(3), 173–186.

Young, D. (2015). The report on small firms 2010–2015; by the Prime Minister’s advisor on enterprise. Information Policy Team, the National archives, Kew, London. Retrieved July 19, 2016, from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/402897/Lord_Young_s_enterprise_report-web_version_final.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Marshall, S., Williams, S. (2019). An Investigation into the Sustainable Actions of Micro- and Small Businesses. In: Crowther, D., Seifi, S., Wond, T. (eds) Responsibility and Governance. Approaches to Global Sustainability, Markets, and Governance. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1047-8_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1047-8_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-1046-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-1047-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)