Abstract

Inequalities play a major role in political and ethnic conflicts in different regions of the world. However economic literature has largely focused on vertical inequalities, i.e. inequalities among individuals as opposed to groups of people. In the recent times the focus has shifted to the role of horizontal inequalities, which refer to inequalities between groups of people sharing common identity such as race, ethnicity, language, religion or region (Stewart 2000). Therefore, they are multifaceted and include various dimensions (for, e.g. socio-economic, political and cultural status). This chapter refers to the recent Bodo-Muslim conflict in the Bodoland Territorial Area Districts of Assam (BTAD) in 2012. We measure economic horizontal inequalities (EHIs) classifying population of BTAD into STs, SCs, OBC, other/general and Muslims using population weighted group Gini index (GGini). NSSO unit level data of 61st and 66th Consumer-Expenditure rounds have been used for calculations. We find that there are significant spatial and horizontal economic inequalities in the BTAD districts compared to the other districts of Assam. Among the social groups, Muslims are found to be the poorest while SCs are better off followed by the STs (mostly Bodos). In Assam as a whole, the extent of land owned by the ST households is found to be the highest while it is lowest among the Muslims. In sharp contrast, land ownership among Muslims is comparatively higher than the other groups (including the dominant Bodo group) in BTAD.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

People in a society with diverse ethnic or religious settings often engage in competition over resources. Bardhan (1997) argues that such competition leaves the marginalised and disadvantaged groups without access to socio-economic and political opportunities, subsequently leading to deprivation. Prolonged periods of relative deprivation may lead to ethnic conflicts causing disintegration in the society (Gurr 1968). The diverse ethno-linguistic groups in the state of Assam have strong aspirations of preserving their own distinct identity and improving socio-economic and political positions including cultural status. Such aspirations have led to intense competition over accessing economic resources and political power (Pathak 2013; Mahanta 2013; Motiram and Sarma 2014). Secessionist and ethno-political conflicts have marred the fabric of Assamese society for a long period of time (Xaxa 2008; Pathak 2013). Some such secessionist conflicts are the Bodoland movement, ethnic clashes between Bodo-Muslim, Bodo-Santhal and Rabha-Non-Rabha groups in the Western Plains region and between Hmar-Dimasa, and Karbi–non-Karbi tribes in the hills districts of Assam. Such conflicts have caused large numbers of deaths and massive internal displacement of population coupled with considerable loss of property.

Bodoland Territorial Area Districts (BTAD) and the districts surrounding them in western Assam is one of the most conflict prone regions of India. It has seen severe massacres and group-based conflicts since the 1990s, besides the secessionist Bodoland movement launched by the indigenous Bodo people since 1960s. The group-based conflicts since the 1990s represent an example of intense ethno-linguistic fractionalization (Motiram and Sarma 2014). The conflict between the Bodo and Muslim groups has been one of the largest in the recent decades, as well as a more recurrent one.Footnote 1 Motiram and Sarma (2014) based on a study of the BTAD, with data from the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), have concluded that group-based inequalities in the region is likely to grow in the coming years.

Studies on the Bodoland secessionist movement by Das (1982), Goswami and Mukherjee (1982), Gohain (1989), Mishra (1989), George (1994), Xaxa (2008), and Basumatary (2012) have highlighted issues surrounding group discrimination, in-migration of non-tribals into tribal areas, alienation of land, and domination of ‘alien’ language and culture. However a systematic study of group-based inequalities based on socio-economic sample surveys has been lacking. In the economic literature, group-based inequalities have been referred as horizontal inequalities as against vertical inequalities that highlight inequalities within groups.

This chapter argues that the presence and perpetuation of horizontal inequalities among different ethnic groups can be used to explain ethno-political conflicts in BTAD and its neighbouring districts. In order to develop this argument, the chapter has used the framework of measuring horizontal inequalities developed by Mancini, Stewart and Brown (2010) to explain civil conflicts. The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) unit level data pertaining to 61st and 66th rounds of Consumption Expenditure and Employment Unemployment for the BTAD districts and Assam have been analysed. NSSO unit level data for Assam as a whole, Western Assam and the BTAD districts have been analysed for three different dimensions. They are (i) average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE), (ii) operational and ownership holdings of land and (iii) administrative positions.

2 Measurement of Inequalities

The civil conflict literature has been rising since the 1990s. Quantitative and econometric approaches to understanding the nexus between ethnicity, inequality and violent conflicts have also been attempted (for example, Fearon and Laitin 2003; Collier and Hoeffler 2004; Dixon 2009; and Lindquist 2012). Many studies have concluded that although theoretically the link between economic inequality and civil (and ethnic) conflicts can be established, empirical evidences do not support a significant cause and effect relationship. For example, the works of Fearon and Laitin (2003) and Collier and Hoeffler (2004) calculated Gini coefficient for income inequality and conducted a regression analysis on ethnic conflicts as the independent variable. They hypothesised a positive relationship between levels of ethnic diversity and propensity to civil conflicts, but empirical investigation did not provide significant results between ‘ethnic fractionalization’ and ‘ethnic civil conflict’ (see Lindquist 2012 for a detailed discussion).

One of the reasons for no conclusive evidence on an empirical relationship between inequalities and ethnic conflicts, it is claimed, could be due to the measure of inequality that is chosen. There is now a sizeable economic literature that focuses on the differences between horizontal inequalities (His) and vertical inequalities (Vis). Vertical inequalities are measured based on extensive use of the techniques of Lorenz ratio and Gini coefficient confined to economic variables such as income, consumption expenditure, or other wealth indicators. They capture the differences between individuals in a society where people are grouped based on a geographical area or on conventional variable(s), such as income, for which inequality can be numerically measured. For example, to measure income inequality people are classified into groups based on geographical location or certain level of income irrespective of their social and ethnic identities. Therefore such measurements fail to capture inequality between the groups sharing common identity; and as such been largely neglected in the development discourse (Stewart 2000; Ostby 2007; Mancini, Stewart and Brown 2010; Lindquist 2012).

Horizontal inequalities are measured grouping the individuals based on non-economic variables like ethnicity, religion and language and thus it can capture the differences in socio-economic conditions between the groups (Stewart 2000 and Ostby 2007). Based on this difference in measure of inequality, economists have sought to inquire the motives behind group mobilisation leading to violence. Many scholars have empirically shown a positive and statistically significant relationship between HIs and risk of violent conflicts (Stewart 2000, 2010; Langer 2005; Tiwari 2008; Mancini 2010). HIs are shown as the basis for group mobilisation and political or ethnic conflicts such as these provide powerful grievances, which the leaders of deprived groups use to mobilise people for political action.

2.1 Concept of Horizontal Inequalities

Unlike VIs, HIs are therefore multifaceted and incl ude socio-economic, political and cultural status dimensions. Horizontal Economic Inequality (HEI) incorporates inequalities in access to and ownership of assets like financial, livestock, human, and social and also in employment opportunities and incomes. HIs in social dimension (HSI) encompasses the variation in access to a range of social services such as education, health care, sanitation, and housing and human outcomes from such services. Horizontal Political Inequality (HPI) occurs when there is inequality in distribution of political opportunities and power including control over the army, participation at the level of cabinet, parliament, bureaucracy and local government. The cultural status horizontal inequality (HCI) reflects the variations in recognition of cultural practices like language, dress, religion and way of living (ibid).

2.2 Role of Horizontal Inequalities in Explaining Ethnic Conflicts

Studies on violent ethnic or political conflicts have strong pointers to HIs as primary cause of conflicts. Differential treatment of people based on language, religion and religious observation, and culture results in identity formation and cleavages among the groups (Langer 2005, 2010, Tiwari 2008; Stewart 2010). Giving priority to the language or religion of one group by recognising as official one, leave others feel undermined and humiliated. This results in deep sense of alienation and frustration among the underprivileged groups which lead to mobilisation along cultural lines (Bardhan 1997; Langer 2005, 2010). For example, the enactment of the 1956 Official Languages Act to make Sinhalese the only official language of Sri Lanka and the 1972 constitutional amendment which gave Buddhism ‘foremost status’ in the country are policies of political and social exclusion of the Tamil minority, which in turn has provoked demands for greater autonomy and armed conflicts (Bardhan 1997). In a society with unequal distribution of political power and opportunities among the elites, the sharp socio-economic inequalities along the cultural differences are often placed in national political sphere. HIs in such a society give strong incentive to both the leaders and people for political mobilisation. Thus, the coexistence of socio-economic and political inequalities along cultural differences create extremely explosive and volatile socio-political situations, as a leader, in such a society, has not only strong incentive for political mobilisation but also can gain easy support from the group members who are also concerned about their own groups’ position (Langer 2010; Brown and Langer 2010; Stewart 2010). In fact, HPI is more likely to motivate the leaders of the excluded groups for agitation. If they fail to fulfil their aspiration through agitation or protests, violence follows.

Stewart (2010) in her study of political mobilisation among the Blacks in South Africa compares the GDP per capita and educational attainment of the whites and blacks. She opines that white minority which had acquired political power through colonial rule used both political power and economic resources to entrench itself politically and enhance its socio-economic conditions. It resulted in sharp socio-economic inequalities between the groups. For instance, it was only 8% of white’s GDP per capita for the Black in 1980. Moreover, relatively much higher expenditure on schooling and healthcare services on each White child compared to the Black resulted in poor education and health outcomes among the Blacks compared to the Whites. She documents that socio-economic HIs are the major cause of political mobilisation among the Blacks in South Africa. Similarly, Ostby (2007) in her study of civil conflicts in 55 developing countries during 1986–2003 measures HIs in terms of three alternative group identifiers like ethnicity, religion and region. She measures HEI based on variation in household assets while HSI on educational attainments among the groups. HIs in both dimensions are found to have positive effect on the probability of conflict.

Mancini (2010) also draws same inference for conflicts in Indonesia. He measures HIs in terms of education, land ownership, public sector employment and child mortality rates to test their link with conflicts. He finds that the HIs in all dimensions have positive association with the likelihood of deadly conflicts. Among these four dimensions, HIs in child mortality rates is found to have strongest impact on conflicts. He argues that group differences in child mortality rates reflect inequalities in other socio-economic conditions like, household wealth, levels of education, housing conditions and so on. Other studies on ethnic or separatist conflicts break-out in different countries, for instances studies on Maoist mobilisation in Nepal by Murshed and Gates (2005), Tiwari (2008), Nepal et al. (2011), and conflicts in Indonesia, Philippines and Coat d’Ivoire by Brown and Langer (2010) have also shown positive association of HIs with violent conflicts.

The perceptions of people on group identity and their impact in access to public amenities and services, and on favouritism and discriminatory attitude of the government also play significant role in escalating such ethnic or separatist conflicts (Langer and Ukiwo 2010; Stewart 2010). Langer and Ukiwo (2010) in their comparative study of Ghana and Nigeria find that perception has played a significant role in escalating severe ethno-communal and religious conflicts. While in Ghana majority of the people regard occupation and nationality as important identity of people, in Nigeria the ethnicity/language, religion and region are regarded important. Relatively larger proportions of people in Nigeria than Ghana perceive that the ethnic or religious background affects access to government amenities and services. This difference in perception of people in Nigeria and Ghana is shown as an important reason, of why Nigeria has been facing recurrent ethno-communal and religious conflicts, while Ghana is able to avoid such conflicts despite both the countries facing similar measured socio-economic inequalities including political exclusion among the groups (Langer and Ukiwo 2010). Prevalence and rising HIs therefore are shown as major factor provoking ethnic strife or secessionist movements in many countries. Both the perceived and measured HIs provide strong grievances to the deprived groups for political mobilisation, protest and agitation against the government or advanced groups.

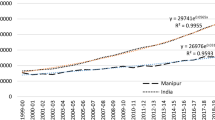

3 Demographic Profile of Assam

Assam’s prolonged secessionist and ethno-political conflicts also deserves attention within this paradigm of horizontal inequalities and ethnic conflicts. The state of Assam has been home to diverse ethnic, religion and cultural groups. Its population has risen to 3.12 crore in 2011 from 2.66 crore in 2001 and 2.44 crore in 1991 at an annual growth rate of 1.75 and 1.60 between 1991–2001 and 2001–2011, respectively. Following the social group classification followed in rest of the country, population of Assam may also be broadly classified into general, schedules castes and scheduled tribe households. Among them, non-tribal and non-SC population forms the majority, who speak Assamese, Bengali and a mix of other languages. Both the STs and SCs represent 12 and 7% respectively as per census, 2011. The ST population of Assam consists of 22 different ethno-linguistic groups such as Bodos, Mising, Mikir/Karbi, Rabha, Deori, Nagas, Khasis, etc. who speak their own dialect. The SCs consist of 17 groups of people like Basfors, Banyas, Dhobis, Hira and so on. Among the tribal population, Bodos constitute a numerically large group, representing nearly a quarter (41%) followed by Mising (18%) and Karbi (11%) as per census of India, 2001 (Table 5.1).

The people of Assam have also been classified into six major religion groups: Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jains, Muslims and Sikhs (Tables 5.4 and 5.5). Among them, the Hindus with 61% are majority as per census of 2011. The Muslims in BTAD represent 19% as against constituting 34% of the total population in the state. The classification of people based on socio-religious groups have shown that people belong to OBC and general categories altogether comprise 44% in western Assam (Table 5.5). Between 1991 and 2001, among the socio-religious groups, growth rate of Muslim population with 2.6% per annum has been the highest while it is the lowest among the SCs (0.01% in Western Assam and 0.9% in Assam). The growth rate among the STs on the other hand in the western Assam has been recorded at 0.6% as against 1.42% in the state as a whole.

The BTAD region is inhabited by various ethno-linguistic and religious groups. It is said that the Bodo Accords have left the non-Bodo people with fear of losing legitimate democratic rights and of being deprived from socio-economic opportunities (Mahanta 2013). Gradually it has resulted in cleavages between the Bodo and non-Bodo groups in BTAD. Formation of the Oboro Surakshya Samiti (Non-Bodos Protection Committee) and the Sanmalita Janagastia Sangram Samiti (SJSS: United Ethnic Peoples’ Struggle Committee) bears evidence of this (Mahanta 2013 and Pathak 2013). These organisations have been holding protests before and after creation of the BTC. Leaders of the non-Bodo organisations have the perception that BTC government favours the Bodos only (Mahanta 2013). They also claim that all the educational institutions, hospitals, government departments are set up only in the Bodo-dominated areas apart from disproportionate representation of the Bodos in employment and administrative sector (ibid). Therefore there is a perception that socio-economic and political resources and unequally distributed among the groups.

4 Methodology

In this study, we use group Gini (GGini) coefficient based on Mancini, Stewart and Brown (2010) to measure economic inequality among the social groups. Gini coefficient, a widely used approach, measures variance in performance of each group with every other group, where observations are grouped based on the variable for which inequality is measured (Ray 2010). However, measuring HIs requires grouping the individuals based on non-economic variables such as ethnicity, religion or caste. We group the individuals based on religion and caste to measure inequalities among them. Since the number of individuals is not same for all the groups an un-weighted measurement would attach equal weight to all groups and thus the changes in position of very small group would have the same effect as the large group (Mancini, Stewart and Brown 2010). Therefore, weights attached are based on population share of each group. In addition to that, we test if the inequality among the groups is statistically significant using one-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA).

4.1 Measurement of HIs

where \(\overline{Y}\) is mean of variable (say average MPCE of all groups), R = population size of Rth group (Say population size of Muslims), S = population size of Sth group (say population size of STs), \(\overline{Y}_{r}\) is mean of variable for group R (say MPCE of Muslims), \(\overline{Y}_{s}\) is mean of variable for group S (say MPCE of STs), P r is share in total population of group R or Muslims, and P s is share in total population of group S or STs.

4.2 Data Source

To measure HEI and establish causal connections with group-based conflicts, we have to depend on a reliable dataset. The sources of data used for this study are Census of India and National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). Population data by different social groups are based on 1991, 2001 and 2011 census. Census data are available on household amenities and occupations however the data cannot be disaggregated by social groups. Thus census data are not enough to fulfil our objective. Similarly the NSS, though it collects nationally representative large sample data for estimating important socio-economic parameters, it furnishes information merely at state level. Since our objective is to measure HIs in the BTAD, we have used unit level data of NSS. The NSSO 61st (2004–2005) and 66th (2009–2010) Consumption Expenditure and Employment Unemployment round data have been used to calculate the population weighted group Gini coefficients.

4.3 NSS Unit Level Data Used in the Study

NSS collects data from large sample surveys conducted throughout the country and provides important information on various socio-economic aspects which are relied on by policy makers, researchers and planning agencies. The NSS classify each state into numbers of sub-state or region to select first stage unit (FSU), i.e. sample villages in rural and blocks in urban sectors from which sample households are surveyed. Sample villages are selected in rural areas taking district as strata while the sample blocks are selected from a sub-region or strata which are formed based on the size class of town (Chaudhuri and Gupta 2009). Thus, the surveys allow reliable estimate at regional level but not at district level. Regional-level estimation could be made for the purpose of our study if our concerned districts were included in a region. But the districts we have considered are spread across different regions. For example, in 56th round of survey, Assam has been classified into three sub-regions: Plains eastern, Plains western and Hills. The BTAD districts of Bongaigaon, Barpeta and Nalbari were included in Plains eastern, Kokrajhar in Hills region while Darrang, Dhubri and Kamrup in Plains western. However, there have been shifts in sampling design since the 61st round (2004–2005).

The new sampling design defined district as strata where both the rural and urban sectors are taken as part of that district for selection of sample villages and blocks from both the sectors allowing estimation at district level too. Moreover, each sector or stratum has been divided into two sub-stratums to select FSUs from the districts. Villages within each district in the sample frame have been arranged in ascending order of population and then the sub-stratum has been demarcated in such a way that each sub-stratum comprises a group of villages and has more or less equal number of population. Similarly, the urban sub-stratum has been framed in such a way that each sub-stratum has more or equal number of blocks or FSUs. Thereafter, sample villages and blocks have been selected from each sub-stratum of a district.

For selecting households from the selected villages or blocks, the households are further classified into three second stage stratum (SSS). In rural sector, households are classified into relatively affluent households, households with principal earnings from other than agriculture activities and other households. Classification of the households in the urban sector on the other hand has been made on the basis of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE). Based on this classification two households had been surveyed from the first SSS while four households from each of other two SSS. Since the sampling schemes used in the surveys prior to 61st round allowed to make neither district level estimation nor regional level estimation for our study, we have used two quinquennial surveys of 61st and 66th rounds on ‘consumption expenditure’ and ‘employment and unemployment’ covering about 10 years period from 2004–05 to 2009–10.

As already discussed, the specific dimensions used to measure horizontal inequalities are average MPCE, ownership and operational holdings of land and administrative positions held by households in the sample dataset.

MPCE is defined as ratio of the aggregate household consumption expenditure referring monetary value of consumption of various goods and services during a reference period to household size. Entitlement of land ownership is measured based on extent of land owned and land possessed. The former refers to a piece of land owned by any member of household vested with the permanent heritable ownership with or without right to transfer, while the latter refers to land owned including leased-in and neither leased-in nor leased-out (i.e. encroached) excluding leased-out land. Based on National Classification of Occupation (NCO) we have taken five sub-groups of occupation like legislators and senior officer, managers, professionals and technicians, and clerks (office and customer service clerks) and renamed as administration. These are the occupations associated not just with security but also with the matter of ethnic pride and prestige. Many researchers have used these occupations to measure HPI (e.g. see Otsby 2007; Tiwari 2008).

4.4 Data Limitations

Small size of sample of each district that may not cover all the social groups prevent us from having district level estimates of socio-economic parameters by social groups. Therefore, we estimate the socio-economic status of the various social groups at regional level. We group the four districts of BTAD with their original districts and rename it Western Assam. It comprises eight districts of Barpeta, Bongaigaon, Darang, Dhubri, Kamrup, Kokrajhar, Nalbari and Sonitpur based on 61st round survey while 12 districts including new districts of Baksa, Chirang, Kamrup Metro and Udalguri in the 66th round survey. One more limitation of using the unit level data for us is that information are collected by classifying population broadly into four groups: scheduled tribes (STs), scheduled castes (SCs), other backward classes (OBC) and others/general but not collected ethnicity wise. Thus the surveys do not have separate information for Bodo ethnic group. However, the Bodos represent the STs in western Assam as they constitute more than 70% of total ST population in the eight districts based on census of 2001 (Table 5.2). Therefore, socio-economic status of the STs can be treated as that of the Bodos. The surveys on the other hand have extensive religion-wise information as the information is collected classifying people into eight major religion groups. The socio-religious classification of the people is mutually exclusive and thus it is possible to identify a household of any religious group and which social category that household belongs to. That makes it possible for us to separate household of a religious group from any social group. We have excluded Muslims from all social categories (STs, SC, OBC and other) and categorised them as a separate group for the sake of our study. Based on NSS’s socio-religious classification we have grouped households into five categories: Muslims, STs, SCs, OBC and General.

5 Horizontal Inequalities for Assam Based on Group Gini

Consumption expenditure, entitlement of land ownership and occupations are important indicators of economic status of people in a society. For example in rural sector, majority of households depend on agriculture and allied activities. The land therefore serves as means of livelihood for many households in rural sector by giving employment and earning opportunities. The variations in distribution of and access to these variables among the different social groups indicate economic inequalities in a society. Hence, we have taken monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE), land ownership and occupation to measure HIs. The preceding table depicts HEI measured by population weighted group Gini (GGini) which implies higher the values more the inequalities.

5.1 Horizontal Inequalities in Consumption Expenditure

The GGini value measured by MPCE is statistically significant across the regions in both the years (see Appendix Table 5.10 to 5.14). The inequalities in western Assam had risen from 0.36 in 2004–2005 to 0.47 in 2009–2010 while in whole Assam it had risen from 0.35 to 0.45 during that period. Thus, the HI in western Assam has not only been higher than that of whole Assam but also has risen at greater magnitude. Among the social groups, the consumption expenditure of the Muslims is the lowest across the regions in both the years (Table 5.7). Similarly, the MPCE of STs in both Assam (Rs. 571 in 2004–2005 and Rs. 890 in 2009–2010) and western Assam (Rs. 589 in 2004–2005 and Rs. 881 in 2009–2010) has been lower not only the average MPCE of whole Assam (Rs. 591 in 2004–2005 and Rs. 933 in 2009–2010) and that in western Assam (Rs. 581 in 2004–2005 and Rs. 893 in 2009–2010) but also that of all other groups.

It is worth to note that HIs in BTAD is relatively lower in comparison to that in other regions as indicated by its GGini value 0.33 compared to 0.45 and 0.47 of whole Assam and western Assam respectively during 2009–2010. However, consumption expenditure of all the groups in BTAD is relatively lower than that of their respective own groups in both Assam and western Assam in 2009–2010. For example, average MPCE of Muslims in BTAD has been recorded at just Rs. 575 compared to own group’s MPCE Rs. 764 and Rs. 732 in western Assam and whole Assam respectively in 2009–2010. Similarly, MPCE of general group with Rs. 748 in BTAD was much lower than its MPCE (Rs. 1152) in whole Assam during that year.

5.2 Horizontal Inequalities in Operational and Ownership Holding of Land

Similar statistically significant inequalities in entitlement of land ownership have been found in both the whole Assam and western Assam (see Table 5.15 to 5.24). It is also observed from the Table 5.3 that inequalities in land ownership have reduced in 2009–2010 in both the regions. Inequality in land owned in western Assam which was significant at 1% level in 2004–2005 had become significant at 5% level in 2009–2010. The fall in inequality in land ownership may be resulted by fall in the gap between the highest and lowest extents of land ownership during 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. For example, the difference in the land owned between the Muslims and STs in whole Assam was 0.54 hectares (1.24 hectares of STs and 0.70 hectares of Muslims see Table 5.8) in 2004–05 which had fallen to 0.35 hectares (1.11 hectares of STs and 0.77 hectares of Muslims) in 2009–2010. Similarly in western Assam, the land owned (1.32 hectares) and possessed (1.31hectares) of STs in 2004–2005 fallen to 0.70 and 0.76 hectares of owned and possessed respectively in 2009–2010 causing fall in gaps between the highest and lowest extents. The GGini values measured by land owned (0.27) and land possessed (0.36) in BTAD have been lower than the respective values for both the state as a whole and western Assam in 2009–2010. Moreover, inequality in land owned is not statistically significant while that with respect to land possessed is significant at 5% level in BTAD during 2009–2010. Thus BTAD’s HIs in land ownership entitlement is not only less compared with other regions but also statistically less significant. However, it is interesting to note that the land ownership among the Muslims is found relatively lower than the extent of ownership of the other groups in both the western Assam and whole state in 2009–2010. In sharp contrast, extent of land ownership among the Muslims is relatively higher than the other groups including the STs (dominant groups) in BTAD the group which has highest extent of ownership in other regions.

5.3 Horizontal Inequalities in Administrative Position

Horizontal inequalities in BTAD as measured by MPCE and land owned have been found relatively lower in comparison to that of other regions. However, its HEI (0.99) based on administrative as principal earning source or primary occupation of the household have been found statistically significant as well as relatively higher than those in both western Assam (0.87) and whole state (0.98) in 2009–2010. The proportion of the household belongs to different social groups with this occupation indicates the Muslims household is the lowest in entire regions in 2009–2010 (see Table 5.9). It is also observed that households with administrative as principal occupation of all the social groups except the SCs in BTAD are relatively lower than their respective groups in both the western Assam and the state of Assam as a whole in 2009–2010.

6 Conclusion

Analysis of NSSO unit level data shows that horizontal or group-based inequalities do exist in Assam. The level of inequality based on group Gini estimate is found to be highest in the dimension of administrative positions, followed by land possessed, land owned and by average monthly per capita consumption expenditure. The GGini estimates for both the 61st and 66th rounds are found to be statistically significant in all the dimensions. As far as the dimension of administrative positions is concerned, horizontal inequalities seem to have consistently risen between the period 2004–2005 and 2009–2010. In fact, group-based inequalities based on administrative positions are found to be close to 1 in Western Assam in 2004–2005 and in BTAD in 2009–10.

The average MPCE estimates show that the levels of consumption expenditure in BTAD are the lowest compared to Western Assam and Assam. Similarly, the proportion of population holding administrative positions is also lowest in BTAD, and this is true across all social groups (including the Bodo and Muslim groups). While proportion of population holding administrative positions are very low in BTAD when compared to Western Assam and Assam, Gini close to 1 shows that inequality within groups in BTAD is extremely high.

Notes

- 1.

The effects of this conflict are even worse than the widely discussed case of Gujarat in 2002 (ibid). People from northeastern origin were targeted in Pune, Bangalore, Mumbai and other parts of the countries as retaliation of this conflict. It left 65 dead, hundreds of wounded and loss of properties by affecting 5780 villages (Chirang and Kokrajhar District Administrations 2015). Besides, the Bodoland secessionist movement claimed 1607 lives in Assam out of which more than 80% were inhabitant of original districts of BTAD over a period of 16 years from 1987 to 2003 (BTC 2013).

References

Bardhan, P. (1997). Method in the madness? A political-economy analysis of the ethnic conflicts in less developed countries. World Development, 25(9), 1381–1398.

Basumatary, K. (2012). Political economy of bodoland movement. New Delhi: Akash Publishing House.

Brown, G. K., & Langer, A. (2010). Cultural status inequalities: An important dimension of group mobilization. In Frances Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: understanding group violence in multiethnic society. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chaudhuri, S., & Gupta, N. (2009). Levels of living and poverty patterns: A district-wise analysis for India. Economic and Political Weekly, XLIV, 9, 99–110.

Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (2004). Greed versus grievance in civil war. Oxford Economic Paper, 56, 563–595.

Das, N. (1982). The Naga movement. In K. S. Singh (Ed.), The tribal movement in India (Vol. 1). Pathna: Manohar Book Service.

Dixon, J. (2009). What causes civil war? Integrating quantitative research findings. International Study Review, 11(4), 707–735.

Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review, 57(1), 75–90.

George, J. S. (1994). The Bodo movement in Assam: Unrest to accord. Asian Survey, 34(10), 878–892.

Gohain, H. (1989). Bodo Stir in perspective. Economic and Political Weekly, 24(25), 377–1379.

Goswami, B. B., & Mukharjee, D. B. (1982). The Mizo political movement. In K. S. Singh (Ed.), The tribal movement in India (Vol. 1). Pathna: Manohar Book Service.

Government of Bodoland Territorial Council. (2013). Kokrajhar: The Bodoland Guardian.

Gurr, T. (1968). A causal model of civil strife: A comparative analysis using new indices. The American Political Science Review, 62(4), 1104–1124.

Langer, A. (2005). Horizontal inequalities and violent conflicts: Cote d’Ivoire. Human Development Report Office, Occasional Paper 2005/32. New York: UNDP.

Langer, A. (2010). When do horizontal inequalities lead to conflicts? Lessons from a comparative study of Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. In Frances Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic Society. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Langer, A., & Ukiwo, U. (2010). Ethnicity, religious and state in Ghana and Nigeria: Perceptions from the street. In Frances Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic society. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lindquist, M. K. (2012). Horizontal education inequalities and civil conflict: The nexus of ethnicity, inequality, and violent conflict. Undergraduate Economic Review, 8(1), 1–21.

Mahanta, N. G. (2013). Politics of space and violence in Bodoland. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(23), 49–58.

Mancini, L. (2010). Horizontal inequalities and communal violence: Evidence from Indonesia districts. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: understanding group violence in multiethnic societies. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mancini, L., Stewart, F., & Brown, G. K. (2010). Approaches to the measurement of horizontal inequalities. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group Violence in Multi ethnic Societies (pp. 85-105). UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mishra, U. (1989). Bodo stir: Complex issues. Unattainable Demands. Economy and Political Weekly, 24(21), 1146–1149.

Motiram, S., & Sarma, N. (2014). The tragedy of identity: Reflection on violent social conflict in Western Assam. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(11), 45–53.

Murshed, S. M., & Gates, S. (2005). Spatial-horizontal inequalities and the maoist insurgency in Nepal. Review of Development Economics, 9(1), 121–134.

Nepal, M. A., Bohara, K., & Gawande, K. (2011). More inequality, more killings: The maoist insurgency in Nepal. American Journal of Political Science, 55(4), 886–906.

Ostby, G. (2007). Horizontal inequalities, political environment and civil conflict evidence from 55 developing countries 1986–2003. World Bank Policy Research Paper 4193.

Pathak, S. (2013). Ethnic violence in Bodoland. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(34), 19–23.

Ray, D. (2010). Development economics. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, F. (2000). Crisis prevention: Tackling horizontal inequalities. Oxford Development Studies, 28, 245–262.

Stewart, F. (2010). Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic society. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tiwari, B. N. (2008). Horizontal inequalities and violent conflict in Nepal. Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 28(1), 33–48.

Xaxa, V. (2008). State, society, and tribes: Issues in post Colonial India. India: Pearson Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 5.1

See Tables 5.4, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 5.8 and 5.9.

Appendix 5.2

List of ANOVA tables.

See Tables 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, 5.15, 5.16, 5.17, 5.18, 5.19, 5.20, 5.21, 5.22, 5.23 and 5.24.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Boro, R., Bedamatta, R. (2017). Can Horizontal Inequalities Explain Ethnic Conflicts? A Case Study of Bodoland Territorial Area Districts of Assam. In: De, U., Pal, M., Bharati, P. (eds) Inequality, Poverty and Development in India. India Studies in Business and Economics. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6274-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6274-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-6273-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-6274-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)