Abstract

This chapter pursues the question whether postsyntactic reordering is a necessary component of UG (as in DM), or (can)not (be) (as in Antisymmetry). A typology of morpheme ordering is developed based on the typology of word order patterns characterized by (Greenberg’s) Universal 20 (U20), modeled by Cinque (Linguistic inquiry 36: 315–332, 2005), and since shown to characterize the typology of word orders in other syntactic domains. Under a syntactic antisymmetry account, morpheme orders are expected to track the syntactic U20 patterns. In syntactic theories without Antisymmetry and with head movement, no such expectations hold, and postsyntactic morpheme reordering must be assumed, If postsyntactic reordering is not available in UG, morpheme orders that have been argued to require postsyntactic reordering in DM should fall within the allowable U20 typology. This chapter looks at a puzzling morpheme order paradigm from Huave, argued by Embick and Noyer (2007), to require postsyntactic local dislocation. It shows that a local dislocation account is ill-motivated, regardless of antisymmetry. This puzzling paradigm turns out to be unremarkable, given the expected U20 syntactic typology. This chapter further develops and tests the antisymmetric U20 account for Huave, and shows that the morpheme alternations can be captured successfully without any need for postsyntactic reordering. It has the advantage of relating specific morpho-syntactic problems to general syntactic configurations, and is shown to extend to capture morpheme order variation within varieties of Huave.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Deciding if some element is semantically vacuous or not is more challenging than often assumed.

- 2.

The following are close to traditional assumptions about lexical entries. This is probably the major difference with nanosyntax.

- 3.

Chris Collins and Richard Kayne (p.c).

- 4.

See Koopman (2014) for “size” restrictions imposed by ph. These properties range from “no bigger than a light foot,” to no bigger than “root”, or “no bigger than phrases of size x derived through pied-piping”, to specifications how deeply embedded in the syntactic structure phonological material is allowed to occur. They can be directly read off from the output of the syntactic derivation (cf. the complexity filters in Koopman and Szabolcsi (2000), and “grafts” on structure building EPP features in Koopman (2014)).

- 5.

- 6.

Universal 20 also plays a central role in Nanosyntax.

- 7.

The generalizations hold up in Cinque’s own now quite extensive database of 1535 languages as of April 30, 2015. Of the potential counterexamples, Cinque (pers. com.), only one could perhaps be qualified as a genuine counterexample.

- 8.

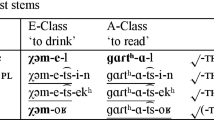

Frequency of patterns is omitted from Table 2.1.

- 9.

Abels and Neeleman (2009) propose an analysis without the LCA/ antisymmetry, which permits right and left adjunction, but restricts movement to leftward movement.

- 10.

I am not concerned here with the question of how this is achieved technically.

- 11.

Here and below, I use small caps p to remind the reader of the phrasal nature of the moved constituent.

- 12.

It remains to be seen to what extent prenominal order can also be the effect of Internal merge (movement). See Koopman and Szabolcsi (2000: 24–25) for arguments that a 1 2 3 4 order in verbal complexes in Hungarian must be the result of internal merge, i.e., movement.

- 13.

The failure of nominal complements to pied-pipe with the N is often taken to be problematic for phrasal movement, and support head movement. This presupposes that nouns do take complements, or/and that complements can remain in their thematic positions. Neither assumption has empirical support (Kayne (1994); Kayne (2000, Chaps. 14, 15), Kayne (2005, Chap. 7), and Hoekstra (1999) among others). This means that a N is both a N and an NP, compatible with either a head movement or a phrasal movement analysis.

- 14.

See Cinque (2009) for examples and references of relative orders of attributive adjectives, relative orders of different types of adverbs, the order of tense, mood, aspect and V, Directional Locative P NP, clitic complexes preverbally or postverbally, verbal complexes in Germanic (cf. Koopman and Szabolcsi (2000) on verb clusters in Hungarian, Dutch, and German; Barbiers (2005), Wurmbrand (2006), and Abels (2011), who is the first to demonstrate that the hierarchy/order relations four-membered Germanic verb clusters track the U20 patterns in the noun phrase.

- 15.

These orders are ruled out by the Final over Final constraint of Biberauer et al. (2014). Since such orders are clearly attested, a different account is needed for the dislike languages often have for right-branching structures before a head.

- 16.

I make no attempt here to contrast this approach to the account in Hyman (2003).

- 17.

We (incl.) lacks −s− a- kohch- ay- on “we (incl.) cut ourselves.” The default plural-n cooccurs with 1/2 person, the third person plural form is a fused form. The fact that both person and number are expressed on the plural suffix is probably important (see section (22)).

- 18.

In Kim (2008) layered affix fields for Huave of San Fransisco, Refl is also closer to the verb root and then the “mobile” first person suffix −s−.

- 19.

Kim (2010) argues the placement of mobile affixes is driven by phonology. Affixes (mobile and nonmobile alike) occur at a fixed distance from the root relative to other affixes. Mobile affixes prefix to vowel initial stems, but suffix to consonant initial stems, to avoid vowel epenthesis. This is incompatible with the U20 view of morpheme order presented here, and remains to be addressed.

- 20.

Ralf Noyer and Yuni Kim (p.c).

- 21.

See Koopman (2015) for a suggestion under what circumstances subextraction in the syntax could be expected to be possible: What is at issue is whether this configuration is always an island, or sometimes.

References

Abels, K. 2011. Hierarchy-order relations in the germanic verb cluster and in the noun phrase. Groninger Arbeiten zur Germanistischen Linguistik 53 (2): 1–28.

Abels, K., and A. Neeleman. 2009. Universal 20 without the LCA. In Merging Features: Computation, Interpretation, and Acquisition, ed. J. Brucart, A. Gavarro, and J. Solá, 60–79. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, M. 1985. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16 (3): 373–416.

Barbiers, S. 2005. Theoretical restrictions on geographical and individual word order variation in Dutch three-verb clusters. In Syntax and variation: Reconciling the biological and the social, 233–264. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Biberauer, T., A. Holmberg, and I. Roberts. 2014. A syntactic universal and its consequences. Linguistic Inquiry 45 (2): 169–225.

Bobaljik, J. 2015. Distributed morphology, to appear in a handbook.

Bobaljik, J.D. 2012. Universals in comparative morphology: Suppletion, superlatives, and the structure of words, vol. 50. MIT Press.

Buell, L.C. 2005. Issues in Zulu verbal morphosyntax. ProQuest.

Caha, P. 2009. The nanosyntax of case. PhD dissertation. Tromsoe.

Chomsky, N. 1992. A minimalist program for linguistic theory, vol. 1. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT.

Cinque, G. 2010. The syntax of adjectives: A comparative study. MIT Press.

Cinque, G. 2009. The fundamental left-right asymmetry of natural languages. In Universals of language today, 165–184. Berlin: Springer.

Cinque, G. 2005. Deriving greenberg’s universal 20 and its exceptions. Linguistic inquiry 36 (3): 315–332.

Cinque, G., et al. 1994. On the evidence for partial n-movement in the romance DP. In Path towards universal grammar, ed. G. Cinque, J. Koster, J.-Y. Pollock, L. Rizzi, and R. Zanuttini, 85–110. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Embick, D., R. Noyer. 2007. Distributed morphology and the syntax/morphology interface. The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces 289–324.

Embick, D., and R. Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32 (4): 555–595.

Greenberg, J.H. 1963. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In Universals of language, ed. J. Greenberg. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Halle, M., and A. Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, ed. K. Hale, and S.J. Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Harley, H. 2012. Semantics in distributed morphology. Semantics: International Handbook of Meaning 3.

Hoekstra, T. 1999. Parallels between nominal and verbal projections. In Specifiers, ed. D. Adger, B. Plunkett, G. Tsoulas, and S. Pintzuk, 163–187. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyman, L.M. 2003. Suffix ordering in Bantu: A morphocentric approach. In Yearbook of Morphology 2002, 245–281. Berlin: Springer.

Joshi, A. 1985. How much context-sensitivity is necessary for characterizing structural descriptions. In Natural language processing: Theoretical, computational and psychological perspectives, ed. D. Dowty, L. Karttunen, and A. Zwicky, 206–250. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Julien, M. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. Oxford University Press.

Kayne, R. 2010. Toward a syntactic reinterpretation of harris and halle (2005). Die Berliner Abendbla¨tter Heinrich von Kleists: ihre Quellen und ihre Redaktion 2 (4).

Kayne, R.S. 2005. Movement and silence, vol 36. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Kayne, R.S. 2000. On the left edge in UG: A reply to Mccloskey. Syntax 3 (1): 44–51.

Kayne, R.S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kim, Y. 2010. Phonological and morphological conditions on affix order in huave. Morphology 20 (1): 133–163.

Kim, Y. 2008. Topics in the phonology and morphology of San Francisco del Mar Huave. ProQuest.

Koopman, H. 2015. Generalized u20 and morpheme order, under review.

Koopman, H. 2014. Recursion restrictions: Where grammars count. In Recursion: Complexity in Cognition, 17–38. Berlin: Springer.

Koopman, H. 2005. Korean (and Japanese) morphology from a syntactic perspective. Linguistic Inquiry 36 (4): 601–633.

Koopman, H.J., and A. Szabolcsi. 2000. Verbal complexes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Muriungi, P.K. 2009. Phrasal movement inside bantu verbs: Deriving affix scope and order in ki-itharaka. PhD thesis, Universitetet i Tromsø.

Muysken, P. 1981. Quechua word structure. Binding and filtering 279–326.

Myler, N. 2013. Exceptions to the mirror principle and morphophonological “action at a distance”: The role of “word”-internal phrasal movement and spell out. New York: ms., New York University.

Pollock, J.Y. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of ip. Linguistic inquiry 365–424.

Ryan, K.M. 2010. Variable affix order: Grammar and learning. Language 86 (4): 758–791.

Sportiche, D., H. Koopman, and E. Stabler. 2013. An introduction to syntactic analysis and theory. New York: Wiley.

Stabler, E. 2011. Computational perspectives on minimalism. In Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism, 617–641. Oxford University Press.

Stairs, E.F., B.E. Hollenbach. 1969. Huave verb morphology. International Journal of American Linguistics 38–53.

Starke, M. 2010. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. Nordlyd 36 (1): 1–6.

Torrence, H. 2003. Verb movement in wolof. Papers in African linguistics 3: 85–115.

Wurmbrand, S. 2006. Verb clusters, verb raising, and restructuring. The Blackwell companion to syntax 229–343.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Koopman, H. (2017). A Note on Huave Morpheme Ordering: Local Dislocation or Generalized U20?. In: Sengupta, G., Sircar, S., Raman, M., Balusu, R. (eds) Perspectives on the Architecture and Acquisition of Syntax. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4295-9_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4295-9_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-4294-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-4295-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)