Abstract

In the present contribution we show that the relaxed micromorphic model is the only non-local continuum model which is able to account for the description of band-gaps in metamaterials for which the kinetic energy accounts separately for micro and macro-motions without considering a micro-macro coupling. Moreover, we show that when adding a gradient inertia term which indeed allows for the description of the coupling of the vibrations of the microstructure to the macroscopic motion of the unit cell, other enriched continuum models of the micromorphic type may allow the description of the onset of band-gaps. Nevertheless, the relaxed micromorphic model proves to be yet the most effective enriched continuum model which is able to describe multiple band-gaps in non-local metamaterials.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the last years, a lot of interest has been raised from a class of microscopically heterogeneous materials which show exotic behaviors such as that of “stopping” the propagation of elastic waves. In some cases, the waves lose some of the energy due to micro-diffusion phenomena (Bragg scattering) or even local resonance of the microstructure (Mie resonance). These effects can be exploited to design innovative materials whose dynamical behavior differs completely from the classical materials usually employed in engineering sciences.

As a matter of fact, classical Cauchy continuum theories, are not always well adapted to cover the wealth of experimental evidences on the dynamical behavior of real materials. As a first point, in fact, real materials commonly show dispersive behaviors, which means that the speed of propagation of the traveling wave changes when considering smaller wavelengths. Such phenomenon is not astonishing if one thinks that the structure of matter changes when observing it at smaller scales. It suffices to go down to the scale of the crystals or molecules to be aware of the heterogeneity of matter. It is for this reason that waves with wavelengths which are small enough to “sense” the presence of the microstruture will propagate at a different speed than other waves with higher wavelengths. Cauchy continuum theories are not able in any case to account for dispersive phenomena and are a good approximation of reality only for those materials which do not exhibit their heterogeneity at the scale of interest. As far as one wants to model dispersive behaviors, Cauchy continuum theories are no longer adapted and more refined models need to be introduced. One possibility is to introduce second or higher order theories so allowing the description of dispersion for the acoustic modes (see e.g. [4, 21]). Nevertheless, if second gradient theories may, on the one hand, be of use for the description of some dispersive behaviors, on the other hand they are often insufficient to describe more complex behaviors of metamaterials in which the microstructure can have its own vibrational modes independently of the motion of the unit cell. In order to describe the complex dynamical behavior of such metamaterials in a continuum framework, the introduction of continuum models with enriched kinematics (micromorphic models) is a mandatory requirement [5, 7, 8, 11, 13]. Continuum models of the micromorphic type, in fact, allow for the description of microstructure-related vibrational modes thanks to the introduction of extra degrees of freedom with respect to the displacement field alone.

The insufficiency of Cauchy continuum theories becomes even more evident when considering more complex metamaterials which are able to inhibit wave propagation, i.e. so called band-gap metamaterials. To catch the complex dynamical behavior of such materials, even some of the available micromorphic models are not sufficiently adapted. Indeed, it has been shown in previous contributions that the relaxed micromorphic model is the only continuum model of the micromorphic type which is able to account for the description of band-gaps when considering a kinetic energy in which the macroscopic and microscopic motions are completely uncoupled [7, 8, 11, 12]. In this contribution we will show, following what done in [10], that the addition of kinetic energy terms which couple the motions of the microstructure to the macro-motions of the unit cells may have a deep impact on the ability of describing band-gaps behaviors.

1.1 Notations

In this contribution, we denote by \(\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}\) the set of real \(3\times 3\) second order tensors, written with capital letters. We denote respectively by \(\cdot \,\), : and \(\left. \langle \cdot ,\cdot \right. \rangle \) a simple and double contraction and the scalar product between two tensors of any suitable order.Footnote 1 Everywhere we adopt the Einstein convention of sum over repeated indices if not differently specified. The standard Euclidean scalar product on \(\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}\) is given by \(\langle {X},{Y}\rangle _{\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}}=\, \mathrm {tr}({X\cdot Y^{T}})\), and thus the Frobenius tensor norm is \(\Vert {X}\Vert ^{2}=\langle {X},{X}\rangle _{\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}}\). In the following we omit the index \(\mathbb {R}^{3},\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}\). The identity tensor on \(\mathbb {R}^{3\times 3}\) will be denoted by \(\,\mathbbm {1}\), so that \(\, \mathrm {tr}({X})=\langle {X},{\,\mathbbm {1}}\rangle \).

We consider a body which occupies a bounded open set \(B_{L}\) of the three-dimensional Euclidian space \(\mathbb {R}^{3}\) and assume that its boundary \(\partial B_{L}\) is a smooth surface of class \(C^{2}\). An elastic material fills the domain \(B_{L}\subset \mathbb {R}^{3}\) and we refer the motion of the body to rectangular axes \(Ox_{i}\).

For vector fields v with components in \(\mathrm{H}^{1}(B_{L})\), i.e. \(v=\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right) ^{T}\,,v_{i}\in \mathrm{H}^{1}(B_{L}),\) we define \(\nabla \,v=\left( (\nabla \,v_{1})^{T},(\nabla \,v_{2})^{T},(\nabla \,v_{3})^{T}\right) ^{T}\), while for tensor fields P with rows in \(\mathrm{H}(\mathrm{curl}\,;B_{L})\), resp. \(\mathrm{H}(\mathrm{div}\,;B_{L})\), i.e. \(P=\left( P_{1}^{T},P_{2}^{T},P_{3}^{T}\right) \), \(P_{i}\in \mathrm{H}(\mathrm{curl}\,;B_{L})\) resp. \(P_{i}\in \mathrm{H}(\mathrm{div}\,;B_{L})\) we define \(\mathrm{Curl}\,P=\left( (\mathrm{curl}\,P_{1})^{T},(\mathrm{curl}\,P_{2})^{T},\right. \left. (\mathrm{curl}\,P_{3})^{T}\right) ^{T},\) \(\mathrm{Div}\,P=\left( \mathrm{div}\,P_{1},\mathrm{div}\,P_{2},\mathrm{div}\,P_{3}\right) ^{T}.\)

A subscript \(_{,t}\) will indicate derivation with respect to time and, analogously a subscript \(_{,tt}\) stands for the second derivative of the considered quantity with respect to time.

As for the kinematics of the considered micromorphic continua, we introduce the functions

which are known as placement vector field and micro-distortion tensor, respectively. The physical meaning of the placement field is that of locating, at any instant t, the current position of the material particle \(X\in B_{L}\), while the micro-distortion field describes deformations of the microstructure embedded in the material particle X. As it is usual in continuum mechanics, the displacement field can also be introduced as the function \(u(X,t):B_{L}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{3}\) defined as

In the remainder of the paper, the following acronyms will be used to refer to the branches of the dispersion curves:

-

TRO: transverse rotational optic,

-

TSO: transverse shear optic,

-

TCVO: transverse constant-volume optic,

-

LA: longitudinal acoustic,

-

LO\(_{1}\)-LO\(_{2}\): \(1^{st}\) and \(2^{nd}\) longitudinal optic,

-

TA: transverse acoustic,

-

TO\(_{1}\)-TO\(_{2}\): \(1^{st}\) and \(2^{nd}\) transverse optic.

If not differently specified, the results presented in this paper are obtained for values of the elastic coefficients chosen as in Table 1 (see Eqs. (1), (2), (5), (8), (11) and (14) for their definition).

1.2 The Fundamental Role of Micro-Inertia in Enriched Continuum Mechanics

As far as enriched continuum models are concerned, a central issue which is also an open scientific question is that of identifying the role of so-called micro-inertia terms on the dispersive behavior of such media. As a matter of fact, enriched continuum models usually provide a richer kinematics, with respect to the classical macroscopic displacement field alone, which is related to the possibility of describing the motions of the microstructure inside the unit cell. The adoption of such enriched kinematics (given by the displacement field u and the micro-distortion tensor P, see e.g. [5,6,7,8,9, 11, 12, 14, 19]) as we will see, allows for the introduction of constitutive laws for the strain energy density that are able to describe the mechanical behavior of some metamaterials in the static regime. When the dynamical regime is considered, things become even more delicate since the choice of micro-inertia terms to be introduced in the kinetic energy density must be carefully based on

-

a compatibility with the chosen kinematics and constitutive laws used for the description of the static regime,

-

the specific inertial characteristics of the metamaterial that one wants to describe (e.g. eventual coupling of the motion of the microstructure with the macro motions of the unit cell, specific resistance of the microstructure to independent motion, etc.).

In the present paper, we will suppose that the kinetic energy takes the following general form (see [10]):

where \(\rho \) is the value of the average macroscopic mass density of the considered metamaterial, \(\eta \) is the free micro-inertia density and the \(\overline{\eta }_{i},i=\{1,2,3\}\) are the gradient micro-inertia densities associated to the different terms of the Cartan-Lie decomposition of \(\,\nabla u\,\). We will be hence able to explicitly show which is the specific role of the gradient micro-inertia on the onset of band-gaps in continuum models of the micromorphic type. More precisely, we will highlight which is the effect of the introduction of gradient micro-inertia terms on different enriched continuum models, namely:

-

the classical relaxed micromorphic model,

-

the relaxed micromorphic model with curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}+||\,\mathrm {Curl}{P}||^{2}\),

-

the relaxed micromorphic model with curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\),

-

the standard Mindlin-Eringen model,

-

the internal variable model.

2 The Classical Relaxed Micromorphic Model

Our relaxed micromorphic model endows Mindlin-Eringen’s representation with the second order dislocation density tensor \(\alpha =-\,\mathrm {Curl}{P}\) instead of the third order tensor \(\nabla {P}\).Footnote 2 In the isotropic case the energy of the relaxed micromorphic model reads

where the parameters and the elastic stress are analogous to the standard Mindlin-Eringen micromorphic model. The model is well-posed in the static and dynamical case including when \(\mu _{c}=0\), see [6, 18].

Here, the complexity of the classical Mindlin-Eringen micromorphic model has been decisively reduced featuring basically only symmetric gradient micro-like variables and the \(\,\mathrm {Curl}\) of the micro-distortion \({P}\). However, the relaxed model is still general enough to include the full micro-stretch as well as the full Cosserat micro-polar model, see [19]. Furthermore, well-posedness results for the static and dynamical cases have been provided in [19] making decisive use of recently established new coercive inequalities, generalizing Korn’s inequality to incompatible tensor fields [2, 3, 15,16,17, 20].

The relaxed micromorphic model counts 6 constitutive parameters in the isotropic case (\(\mu _{e}\), \(\lambda _{e}\), \(\mu _{\mathrm {micro}}\), \(\lambda _{\mathrm {micro}}\), \(\mu _{c}\), \(L_{c}\)). The characteristic length \(L_{c}\) is intrinsically related to non-local effects due to the fact that it weights a suitable combination of first order space derivatives of P in the strain energy density (2). For a general presentation of the features of the relaxed micromorphic model in the anisotropic setting, we refer to [1].

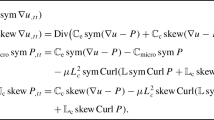

The associated equations of motion in strong form, obtained by a classical least action principle take the form (see [7, 8, 12, 18])

where

The fact of adding a gradient micro-inertia in the kinetic energy (1) modifies the strong-form PDEs of the relaxed micromorphic model with the addition of the new term \(\mathscr {I}\). Of course, boundary conditions would also be modified with respect to the ones presented in [9, 12]. The study of the new boundary conditions induced by gradient micro-inertia will be the object of a subsequent paper where the effect of such extra terms on the conservation of energy will also be analyzed (Fig. 1).

As it has been shown in previous contributions [7, 8, 11], the relaxed micromorphic model is able to capture band-gap behaviors thanks to the fact that the acoustic branches have a horizontal asymptote. We show in Fig. 2 the dispersion relations obtained in previous work which are recovered here setting the gradient micro inertia to be vanishing (\(\overline{\eta }=0\)).

Things are different when adding a gradient micro-inertia \(\overline{\eta }\ne 0\). Surprisingly, the combined effect of the free micro-inertia \(\eta \) with the gradient micro-inertia can lead to the onset of a second longitudinal and transverse band gap, due to the fact that the first longitudinal and transverse acoustic branches (\(LO_{1}\) and \(TO_{1}\)) are flattened. Moreover, it is possible to notice that the addition of gradient micro-inertiae \(\overline{\eta }_{1}\), \(\overline{\eta }_{2}\) and \(\overline{\eta }_{3}\) has no effect on the cut-off frequencies, which only depend on the free micro-inertia \(\eta \) (and of course on the constitutive parameters).

In Fig. 3 we show more explicitly the flattening effect of the gradient inertia parameters on longitudinal and transverse waves. In the same Figure we indicate the main mode of vibration associated to each branch of the dispersion curves. In contrast to Cauchy models, the modes of vibration change when changing the wavenumbers.

In particular, it is possible to notice that the main mode of the acoustic branches is the longitudinal or transverse displacement (as it is the case for Cauchy media) only for very small wavenumbers k (large wavelengths). Increasing the wavenumber (decreasing the wavelength), the longitudinal and transverse vibrations are characterized by a coupling of the modes \(P^{S}\) and \(P^{D}\), and \(P_{(1\xi )}\) and \(P_{[1\xi ]}\), respectively. Moreover, it can be seen that the optic branches are characterized by one main microstructure-related vibrational mode until relatively high values of the wavenumber k. The coupling occurs for higher values of k and it is strongly influenced by the effects of the gradient micro-inertia.

Dispersion relations \(\omega =\omega (k)\) of the relaxed micromorphic model for longitudinal (left) and transverse (right) waves with increasing gradient micro-inertia. The markers indicate the main mode of vibration considering: black triangle \(u_{1}\), black circle \(P^{S}\), black square \(P^{D}\), empty triangle \(u_{\xi }\), empty circle \(P_{(1\xi )}\) and empty square \(P_{[1\xi ]}\) with \(\xi =2,3\). When two markers are present it means that there is no clear main mode

3 The Micromorphic Model with Curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}+||\,\mathrm {Curl}{P}||^{2}\)

We consider now an extension of the relaxed micromorphic model obtained considering the energy (see [11]):

The dynamical equilibrium equations are:

where

Note that the structure of the equation is equivalent to the one obtained in the standard micromorphic model with curvature \(\frac{1}{2}||\nabla {P}||^{2}\), see Eq. (12) in Sect. 5.

We present the dispersion relations obtained with a vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 4) and for a non-vanishing gradient micro-inertia (Fig. 5). We conclude that when considering the model with micromorphic medium with \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\) + \(||\,\mathrm {Curl}{P}||^{2}\) with vanishing gradient micro-inertia, there always exist waves which propagate inside the considered medium independently of the value of frequency even if considering separately longitudinal, transverse and uncoupled waves. On the other hand, switching on the gradient inertia it is possible to obtain a total band-gap.

4 The Micromorphic Model with Curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\)

The isotropic micromorphic model with \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\) is yet another variant of the classical relaxed micromorphic model (see [11]) with energy:

The dynamical equilibrium equations are:

where

We present the dispersion relations obtained with a non-vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 7) and for a vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 6). In the Figures we consider uncoupled waves (a), longitudinal waves (b) and transverse waves (c). Even in this case, when considering the micromorphic model with only \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\) with vanishing gradient inertia, there always exist waves which propagate inside the considered medium independently of the value of the frequency and the uncoupled waves assume a peculiar behavior in which the frequency is independent of the wavenumber k. On the other hand, when switching on the gradient inertia, a behavior analogous to the relaxed micromorphic model appears: it is possible to model the onset of two complete band-gaps. The uncoupled waves remain unaffected by the introduction of the gradient micro-inertia and they keep their characteristic of being independent of the wavenumber in strong contrast to what happen for the relaxed micromorphic model in which the uncoupled waves are dispersive.

5 The Standard Mindlin-Eringen Model

In this section. we discuss the effect on the Mindlin-Eringen of the addition of the gradient micro-inertia \(\overline{\eta }||\,\nabla u\,_{,t}||^{2}\) to the classical terms \(\rho ||u_{,t}||^{2}+\eta ||{P}_{,t}||^{2}\). We recall that the strain energy density for this model in the isotropic case takes the form:

The dynamical equilibrium equations are:

where

Recalling the results of [7], we remark that when the gradient micro-inertia is vanishing (\(\overline{\eta }_{1}=\overline{\eta }_{2}=\overline{\eta }_{3}=0\)) the Mindlin-Eringen model does not allow the description of band-gaps (see Fig. 8), due to the presence of straight acoustic waves. On the other hand, when switching on the parameters \(\overline{\eta }_{2}\) and \(\overline{\eta }_{3}\) , the acoustic branches are flattened, so that the first band-gap can be created (see Fig. 9). The analogous case for the relaxed micromorphic model (Fig. 1) allowed instead for the description of 2 band gaps.

As already pointed out and as shown in [11], the classical Mindlin-Eringen model can be considered to be equivalent to the relaxed micromorphic model with curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}+||\,\mathrm {Curl}{P}||^{2}\).

6 The Internal Variable Model

Figure 10 shows the behavior of the addition of the gradient micro-inertia \(\overline{\eta }||\,\nabla u\,_{,t}||^{2}\) in the internal variable model. We recall (see [19]) that the energy for the internal variable model does not include higher space derivatives of the micro-distortion tensor \({P}\) and, in the isotropic case, takes the form:

The dynamical equilibrium equations are:

where

We present the dispersion relations obtained for the internal variable model with a non-vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 11) and for a vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 10). We start noticing in Fig. 10 that the internal variable model with vanishing gradient micro-inertia allows for the description of two complete band-gap even if it is not able to account for the presence of non-localities in metamaterials. Moreover, by direct observation of Fig. 11, we can notice that, when switching on the gradient micro-inertia, suitably choosing the relative position of \(\omega _{r}\) and \(\omega _{p}\), the internal variable model allows to account for 3 band gaps. We thus have an extra band-gap with respect to the case with vanishing gradient inertia (Fig. 10) and to the analogous case for the relaxed micromorphic model (see Fig. 2), but we are not able to consider non-local effects. The fact of excluding the possibility of describing non-local effects in metamaterials can be sometimes too restrictive. For example, flattening the curve which originates from \(\omega _{r}\) and which is associated to rotational modes of the microstructure is nonphysical for the great majority of metamaterials.

Dispersion relations \(\omega =\omega (k)\) of the internal variable model for the uncoupled (left), longitudinal (center) and transverse (right) waves with non-vanishing gradient micro-inertia. Three band-gap are possible but non-local effects cannot be described. The overall trend of the dispersion curves is unrealistic for the great majority of metamaterials

7 Conclusions

In this paper we make a review of some of the available isotropic, linear-elastic, enriched continuum models for the description of the dynamical behavior of metamaterials. We show that the relaxed micromorphic model previously introduced by the authors is the only non-local enriched model which is able to describe band-gaps when considering a kinetic energy independently accounting for micro and macro motions. As far as an inertia term which couples the micro-motions to the macroscopic motions of the unit cell is introduced, also other non-local models exhibit the possibility of describing band-gap behaviors. Nevertheless, the relaxed micromorphic model is still the more effective one to describe (multiple) band-gaps and non-local effects in a realistic way. In fact, even with the addition of the new micro-inertia term, the relaxed model is able to account for the description of two band-gaps, in contrast with to the single band-gap allowed by the Mindlin-Eringen model. The micromorphic model with curvature \(||\mathrm {Div}{P}||^{2}\) also allows for the description of two band-gaps when considering an augmented kinetic energy, but the uncoupled waves are forced to be non-dispersive: this fact can be considered to be a limitation for the realistic description of a wide class of band-gap metamaterials. Finally, the internal variable model with the new kinetic energy terms allow for the description of up to three band gaps. Nevertheless, the overall trends shown by the dispersion curves turn to be quite unrealistic due to the fact that all the branches of the dispersion curves show very low or no dispersion at all.

Notes

- 1.

For example, \((A\cdot v)_{i}=A_{ij}v_{j}\), \((A\cdot B)_{ik}=A_{ij}B_{jk}\), \(A:B=A_{ij}B_{ji}\), \((C\cdot B)_{ijk}=C_{ijp}B_{pk}\), \((C:B)_{i}=C_{ijp}B_{pj}\), \(\left. \langle v,w\right. \rangle =v\cdot w=v_{i}w_{i}\), \(\left. \langle A,B\right. \rangle =A_{ij}B_{ij}\) etc.

- 2.

The dislocation tensor is defined as \(\alpha _{ij}=-\left( \,\mathrm {Curl}{P}\right) _{ij}=-{P}_{ih,k}\varepsilon _{jkh}\), where \(\varepsilon \) is the Levi-Civita tensor and Einstein notation of sum over repeated indices is used.

References

Barbagallo, G., d’Agostino, M.V., Abreu, R., Ghiba, I.-D., Madeo, A., Neff, P.: Transparent anisotropy for the relaxed micromorphic model: macroscopic consistency conditions and long wave length asymptotics. Preprint arXiv:1601.03667 (2016)

Bauer, S., Neff, P., Pauly, D., Starke, G.: New Poincaré-type inequalities. Comptes Rendus Mathematique 352(2), 163–166 (2014)

Bauer, S., Neff, P., Pauly, D., Starke, G.: Dev-Div- and DevSym-DevCurl-inequalities for incompatible square tensor fields with mixed boundary conditions. ESAIM: Control Optim. Calc. Var. 22(1), 112–133 (2016)

dell’Isola, F., Madeo, A., Placidi, L.: Linear plane wave propagation and normal transmission and reflection at discontinuity surfaces in second gradient 3D continua. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 92(1), 52–71 (2012)

Eringen, A.C.: Microcontinuum Field Theories. Springer-Verlag, New York (1999)

Ghiba, I.-D., Neff, P., Madeo, A., Placidi, L., Rosi, G.: The relaxed linear micromorphic continuum: existence, uniqueness and continuous dependence in dynamics. Math. Mech. Solids 20(10), 1171–1197 (2014)

Madeo, A., Neff, P., Ghiba, I.-D., Placidi, L., Rosi, G.: Band gaps in the relaxed linear micromorphic continuum. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 95(9), 880–887 (2014)

Madeo, A., Neff, P., Ghiba, I.-D., Placidi, L., Rosi, G.: Wave propagation in relaxed micromorphic continua: modeling metamaterials with frequency band-gaps. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 27(4–5), 551–570 (2015)

Madeo, A., Barbagallo, G., d’Agostino, M.V., Placidi, L., Neff, P.: First evidence of non-locality in real band-gap metamaterials: determining parameters in the relaxed micromorphic model. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 472(2190), 20160169 (2016)

Madeo, A., Neff, P., Aifantis, E.C., Barbagallo, G., d’Agostino, M.V.: On the role of micro-inertia in enriched continuum mechanics. Preprint arXiv:1607.07385 (2016)

Madeo, A., Neff, P., d’Agostino, M.V., Barbagallo, G.: Complete band gaps including non-local effects occur only in the relaxed micromorphic model. Preprint arXiv:1602.04315 (2016)

Madeo, A., Neff, P., Ghiba, I.-D., Rosi, G.: Reflection and transmission of elastic waves in non-local band-gap metamaterials: a comprehensive study via the relaxed micromorphic model. J. Mech. Phys. Solids (2016)

Mindlin, R.D.: Microstructure in Linear Elasticity. Technical report, Office of Naval Research (1963)

Mindlin, R.D.: Micro-structure in linear elasticity. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 16(1), 51–78 (1964)

Neff, P.: On Korn’s first inequality with non-constant coefficients. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. Sect. A Math. 132(01), 221 (2002)

Neff, P., Pauly, D., Witsch, K.-J.: A canonical extension of Korn’s first inequality to H(Curl) motivated by gradient plasticity with plastic spin. Comptes Rendus Mathematique 349(23), 1251–1254 (2011)

Neff, P., Pauly, D., Witsch, K.-J.: Maxwell meets Korn: a new coercive inequality for tensor fields in \(R^{n \times n}\) with square-integrable exterior derivative. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 35(1), 65–71 (2012)

Neff, P., Ghiba, I.-D., Lazar, M., Madeo, A.: The relaxed linear micromorphic continuum: well-posedness of the static problem and relations to the gauge theory of dislocations. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 68(1), 53–84 (2014)

Neff, P., Ghiba, I.-D., Madeo, A., Placidi, L., Rosi, G.: A unifying perspective: the relaxed linear micromorphic continuum. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 26(5), 639–681 (2014)

Neff, P., Pauly, D., Witsch, K.-J.: Poincaré meets Korn via Maxwell: extending Korn’s first inequality to incompatible tensor fields. J. Differ. Equ. 258(4), 1267–1302 (2015)

Placidi, L., Rosi, G., Giorgio, I., Madeo, A.: Reflection and transmission of plane waves at surfaces carrying material properties and embedded in second-gradient materials. Math. Mech. Solids 19(5), 555–578 (2014)

Acknowledgements

The work of Ionel-Dumitrel Ghiba was supported by a grant of the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research and Innovation, CNCS-UEFISCDI, project number PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4-0320. Angela Madeo thanks INSA-Lyon for the funding of the BQR 2016 “Caractérisation mécanique inverse des métamatériaux: modélisation, identification expérimentale des paramètres et évolutions possibles”, as well as the CNRS-INSIS for the funding of the PEPS project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Madeo, A., Neff, P., Barbagallo, G., d’Agostino, M.V., Ghiba, ID. (2017). A Review on Wave Propagation Modeling in Band-Gap Metamaterials via Enriched Continuum Models. In: dell'Isola, F., Sofonea, M., Steigmann, D. (eds) Mathematical Modelling in Solid Mechanics. Advanced Structured Materials, vol 69. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3764-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3764-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-3763-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-3764-1

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)