Abstract

This chapter reviews the major theories on self-concept and brand personality in the luxury consumption context. The self-concept is the cognitive or thinking aspect of self, referring to learned beliefs, attitudes, and opinions that each person holds about his or her personal existence. Brand personality is defined as a set of human characteristics associated with a brand, in which a brand may be considered as an active relationship partner rather than a passive exchange object. Linking these two concepts in the luxury context, the chapter considers how person-specific, internal or external attributes, interact to form an individual’s self-concept and how the self links with the brand’s personality. Understanding consumers’ self-concept is particularly important for luxury products and brands due to its the wider implications for consumer psychology and behavior and marketing practice. Hence, theoretical and managerial implications are discussed arising from the self-concept and brand personality (SCBP) framework.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Self-concept

- Brand personality

- Self-congruity

- Luxury brands

- Luxury consumption

- Luxury consumers

- Luxury purchase decision making

1 Introduction

Many consumers are today choosing to purchase products and services that are of a greater value. This is the case for especially the new middle-market consumers that are well educated and well traveled. The feature of luxury brands as a way to demonstrate a luxurious lifestyle that include symbolic effects, expensive taste, individual’s social status and identity (Kapferer 2012), shows the consumers’ underlining uniqueness, enjoyments, conspicuous values, and emotional attachments (Kansara 2011; Wu et al. 2015a). These consumers’ purchasing choices indicate the influential role of luxury brands and products in their decisions and luxury consumption. As more and more middle-market consumers will happily—and capably—pay premiums for better quality of products, well known brands , and luxury branded products (Duma et al. 2016), it therefore becomes interesting to understand further about these luxury consumers’ purchasing decisions when comes to luxury brands.

This chapter reviews the effects of self-concept and the role of brand personality when luxury consumers make purchasing decisions. Both the self-concept and brand personality have received great attention among practitioners and academics alike (e.g., Wu et al. 2015b). Scholars suggest that the self-concept is the cognitive or thinking aspect of self, referring to learned beliefs, attitudes, and opinions that each person holds about his or her personal existence. Brand personality is defined as a set of human characteristics associated with a brand, in which a brand may be considered as an active relationship partner rather than a passive exchange object. Linking these two concepts considers how person-specific, internal or external attributes, interact to form an individual’s self-concept and how the self links with the brand’s personality. Hence, the chapter reviews theories on self-concept, self-esteem, congruity, and brand personality/image, here in the luxury context. A self-concept and brand personality (SCBP) framework is developed and theoretical and managerial implications are discussed.

This chapter will cover the following issues:

-

(a)

Identifying and summarizing the major theories of self-concept and brand personality in the luxury context.

-

(b)

Discussing, interpreting, and ascribing the self-concept and brand personality to the current research agenda .

-

(c)

Choosing and applying an appropriate approach for managing brand personality.

2 Routemap: The Self-concept and Brand Personality Within the Marketing Psychology Framework

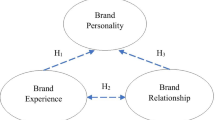

The enthusiasm to acquire luxury brands customarily derives from the impression of conspicuous consumption. This concept tends still to be more or less the strategic establishment for the management of luxury brands (Corneo and Jeanne 1997; Dittmar 1994; Duma et al. 2016; O’Cass and Frost 2002; Vigneron 1999; Vigneron and Johnson 2004). Based on this notion, which has its roots via a consumer’s decision-making process and the social psychological effect via their purchasing intention, ideal social images, and conspicuous purchases (Eagly and Chaiken 1993), brands are employed to differentiate several consumption strategies: (a) brands can be used to underline social salience with visible symbols to highlight a consumer’s taste, and (b) brands can be viewed as an symbol or sign that associate a particular social group with that in which they would like to communicate or engage with as their social identities. A number of researchers have enhanced the fundamental concept of luxury consumption for years (Wong and Ahuvia 1998; Vigneron 1999; Vigneron and Johnson 2004; Tsai 2005; Wiedmann et al. 2009). Building on these previous studies, the chapter topic investigates consumption orientation on the self-concept , particularly as this subject is essential to the wider marketing psychology and consumer behavior literatures due to its focus to the self, that is, who the consumer is and how their thoughts about themselves affect their subsequent brand choice. This chapter further discusses how a personal orientation towards luxury brands is more important for some consumers than others (Wong and Ahuvia 1998), especially when consumers choose a luxury brand based on its utilitarian, emotional, symbolic effects which may reflect on their personal orientations. The discussion explores how a consumer’s self matches with a brand’s personality. The diagram (Fig. 3.1) summarizes the relations among relevant factors (e.g., self-concept, self-esteem, consumer personality, brand personality, and self-congruity).

This chapter, considering attributes that form one’s self-concept , is structured as follows: First, the key theories on self-concept, self-esteem, congruity, and brand personality are reviewed and the literatures’ seminal and most current directions and discusses discrepancies and disagreements are presented. A summary table highlighting the key findings is placed at the end of this section. Then, applying a case study, the chapter illustrates the above concepts in practice. Finally, key questions are put forward for further study with implications for research, theory , and practice.

3 The State of the Art in the Self-concept and Brand Personality

Keller (1998) defines a brand as set of mental associations held by the consumer. These mental associations may add to the perceived value of a product or service . Expanding the notion of perceived value to include all evaluations about the brand and its related information (Peter and Olson 2001), such evaluation of brand related information is referred to as brand equity and, as researchers posit, the outcome of any efficient branding activity investments (e.g., Seetharaman et al. 2001; Han et al. 2015).

Brand equity is considered as the value of a firm’s name and symbol, its strength, currency and value, its description and assessment of the appeal among all target audiences, who interact with the brand (Cooper and Simons 1997). The measurement of brand equity should accurately evaluate consumers’ perceptions of the brands in order to develop marketing strategies that align with both consumers’ values and the self (Gupta et al. 2011). This alignment is relevant not only to consumers who purchase a brand but also to managers and marketers who evaluate the performance of brands and formulate branding strategies. Hence, the evaluation of brand equity presents an efficient way to assess consumers’ behavior and management performance (Richards et al. 1998). In developing and increasing brand equity, firms have turned their attention towards creating brand personalities. Brand personalities enable firms to develop consumer-brand relationships that are more intimate due to the focus on the alignment between self and brand. This alignment, or matching process, is referred to as self-congruity. By addressing how a firm can create a brand personality that is congruent with the consumers’ self, managers can not only understand their consumers’ perceptions and issues related to their self, but also, clearly follow a path that emphasizes the creation of a matching brand personality, in order to communicate with their consumers more successfully. In the next section, the chapter investigates the key theories on how person-specific internal or external attributes interact to form one’s self-concept.

3.1 Self-concept

Self-concept is defined as “the thoughts, beliefs, and concerns that individuals hold about their own attributes and characteristics” (Wright 2006, p. 325). The self-concept is the cognitive or thinking aspect of self (related to one’s self-image) and generally refers to “the totality of a complex, organized, and dynamic system of learned beliefs, attitudes, and opinions that each person holds to be true about his or her personal existence” (Purkey 1988, p. 1). The self-concept is considered as a system structure that forms from interaction of social environment and individual mental behavior information, such as temperament, personality, values, and social roles. It is said to be acquired self-recognition based on psychological genes. Super (1984), drawing from career decision theories, suggest that self-concepts reflects attempts at translating self-understanding into career terms. He proposed that self-concepts contain both objective and subjective elements, and that self-concepts continue to develop over time, making career choices and adjusting them to lifelong tasks. Super (1984) suggested that the self-concept include an individual’s self-esteem and an understanding of the clarity, harmony, development, effectiveness, and personal interest in the development status’ capacity and potential.

In branding, researchers argue that consumers are drawn towards brands that reflect both their actual self and ideal social self-concepts (Rhee and Johnson 2012). Consumers, therefore, are likely to choose brands , which represent their ideal self-concept . Consumers choose brands which are either socially acceptable or reflect their own personality and the brands’ personality, which in turn, reflect who the consumer aspires to be. Scholars note that the consumers’ self-concept identifies whether consumers connect to a brand and why. The three underlying self-concepts are (Graeff 1996; Sirgy 1985; Rhee and Johnson 2012):

-

(1)

Who am I?

-

(2)

Who do I want to be?

-

(3)

Who do I want others to think I am?

Self-image congruity theory, reflecting the three questions above, is where consumers’ brand preferences are determined. These preferences can be determined by matching consumers’ cognitive image with the brands’ image (Sirgy 1986). The self-image congruity theory further suggests that consumers associate their personal image and how they want to be perceived with the brand (Aaker 1997). Scholars have continued to identify, within the consumer and brand relationship domain, two categories of self-concepts, namely, internal and external. Internal variables are those, which are correlated to an individual’s characteristics such as personality. These variables are linked to the question ‘who am I?’ in the self-image congruity theory . External variables concern the external environment and refer to everything else, such as peer pressure. Within the self-image congruity theory, these external variables are associated with ‘who do I want to be’ and ‘who I want others to think I am’. The three underlying self-concepts present a framework for understanding the internal and external factors, which influence the relationship between self and brand.

When exploring the internal self-concept, the theory of self-discrepancy provides a framework for understanding different types of self (Higgins 1987). The self-discrepancy theory states that people compare themselves to internalized standards called self-guides. These are different representations of the self and is divided into three categories: actual self, ideal self, and ought self. The theory states that these self-guides can be contradictory, resulting in emotional discomfort (Orellana-Damacela et al. 2000). Self-discrepancy is the gap between two of these self-representations, and once a gap exists, people are motivated to reduce the gap in order to remove disparity in self-guides (Tindale and Suarez-Balcazar 2000).

In branding, the self-discrepancy theory provides a platform for understanding how different types of discrepancies between varying representations of the self are related to different kinds of emotional vulnerabilities. It, thus, maintains close ties to the belief-incongruity research, including self-inconsistency theory (Lecky 1961), cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1957), imbalance theory (Heider 1958), and equity theory (Adams 1965). By exploring the internal aspect of self, researchers show that internal disagreement causes emotional and psychological turmoil. The theory proposes how a variety of self-discrepancies represent a variety of types of negative psychological situations that are associated with different kinds of discomfort. Thus, it aids in predicting which types of incongruent ideas are causing individuals to feel different kinds of negative emotions related to their brand relationships. Those emotions, in turn, predict consumers’ brand affect leading to positive or negative outcomes, including loyalty, affective commitment, and trust.

Levy (1959) contended that the behaviour of consumers is not functional oriented and is substantially influenced by symbols encountered in the identification of goods in the marketplace. A study by Grubb and Grathwohl (1967) found that each brand often comes with its character and identity that reflects consumers’ ideal selves, which can support them in their self-enhancement activities by giving them the feeling or getting closer to their ideal self. For example, the act of shopping combines an individual’s preference, intentions, meanings and humanistic interactions, which carry deeper meaning and information than observing consumers’ behavioural patterns of purchases (Miller et al. 1998). Shopping covers a wide range of behaviors, either through a social or an individual context. That is, consumers engage in certain behaviour as a way of constructing their self-concept and creating their personal identity (Belk 1988; Richins 1994), especially when some symbolic possessions are associated with certain brands (e.g., some people might use certain brands to associate with others or to counterpart with their personality/identities). These associations can then be transferred from resourcing groups (e.g. friends, family or communities with whom individuals intend to associate) to themselves, as they select brands with meanings that are congruent with an aspect of their self-concept.

As mentioned above, the theory of self-discrepancy postulates three different types of self, namely, actual, ideal, and ought. The ‘actual self’ is a person’s basic self-concept , that is, their perception of own attributes, such as intelligence, attractiveness, and so on (Higgins 1987). Thus, actual self is the representation of the attributes that a person believes he or she possesses, or that he or she believes others believe he or she possesses. The ‘ideal self’ is what motivates a person to change, improve and achieve, focusing on the presence or absence of positive outcomes, such as love. In other words, the ideal self is a person’s representation of attributes that the person would like to, ideally, possess (representation of someone’s hopes, aspirations, or wishes). Finally, the ‘ought self’ is the representation of the attributes that a person believes he or she should or ought to possess, focusing on the presence or absence of negative outcomes, such as criticism. The ought is a representation of a person’s sense of your duty, obligations, or responsibilities (Higgins et al. 1994). Some feature a strong emphasis on “role identities, personal attributes, relationships, fantasies, possession, and other symbols that individuals use for the purpose of self creation and self-understanding” (Schouten 1991, p. 143). The connection between self-concept and individual preferable behaviors might be influenced by product consciousness and conspicuous purchases (Dolich 1969; Ross 1971).

Understanding the self provides a means to systematically lessen negative affect associated with self-discrepancies by reducing the discrepancies between the self-domains in conflict of one another (Higgins 1987). The study of self has been applied to psychological health, but also extensively to branding as a way to understand human emotions. For example, studying consumer emotions, such as shame and guilt, provide an understanding of the level of congruity between the self and the brand identity. If there is a conflict between the self and the brand, a negative response will occur, damaging the brand. In this self-guided society, pressure on individuals often induces turmoil if there are discrepancies between the self and their brands. Hence, the theory finds many of its uses, not only geared towards mental health, anxiety, and depression, but also to understanding what emotions are being aroused, and the reasoning on why it is important to reinstate psychological health. This is particularly true for brands causing negative emotions. In such event, the brand managers must reinstate balance by both investigating the emotions and the level of congruity. These are aspects considered to make up the internal and external variables affecting the self.

In consumer-brand relationships, scholars suggest that individuals internalize their relationship experiences, so that previous relationships develop a pattern for future relationships. This projection reveals how an individual perceive other people and their own image of self (Bowlby 1973; Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991). Individuals’ working models of self and working models of others are principal causes of progression between early attachment (experiences, feelings, cognitions, and behaviors) and future relationships. By understanding these elements, marketers may predict future relationships by designing new proximity-seeking attempts with relational partners, without reconsidering from the very beginning (Gillath et al. 2005). Consequently, an individual’s internal working model may act as a useful guide for consumer-brand relationships.

3.2 Self-esteem

Many products and brands represent a certain image, social role or status to their owners (Sproles and Burns 1994). In order to achieve the perception of a higher social status and social approval, some consumers are encouraged to purchase and display luxury items in a conspicuous demonstration of wealth, advertising their ability to afford luxury goods. Particular clothing and accessories that an individual may own and then wear in public are recognised as status symbols (Solomon and Rabolt 2004). While the self-concept is what individuals think about the self, the self-esteem is the positive or negative evaluations of the self (Smith and Mackie 2007). Self-esteem is known as the evaluative dimension of the self that includes feelings of worthiness, prides, and discouragement, and is also closely associated with self-consciousness (Newman and Newman 1975). Thus, it is a judgment of oneself, the attitude toward the self, and a person’s overall emotional evaluation of his or her own worth. In accordance with social-learning theorists, Olson et al. (2007) define self-esteem as a person’s judgments of their own worthiness, that is, their personal worth or worthiness (Baumeister et al. 1996). According to other researchers, self-esteem is “the experience of being competent to cope with the basic challenges of life and being worthy of happiness.” Branden (1994) notes that self-esteem is the sum of both self-confidence (a feeling of personal capacity) and self-respect (a feeling of personal worth). Self-esteem thus exists as a consequence of a person’s implicit judgment about their ability to face life’s challenges, to understand and solve problems, and their right to achieve happiness, and be given respect.

As a social psychological construct, researchers conceptualize self-esteem as an influential predictor of outcomes, such as academic achievement (Marsh 1990) or exercise behavior (Hagger et al. 1998). In branding, self-esteem has been treated as an important outcome due to its close relation with psychological well-being. Self-esteem applies to a global extent (for example, “I believe I am a bad person, and feel bad about myself in general”) or a particular dimension (for example, “I believe I am a good writer and I feel happy about that”). Several theories, including Maslow’s (1987) hierarchy of needs, suggested that self-esteem is a basic human need or motivation. Maslow stated that psychological health is not possible unless the essential core of the person is fundamentally accepted, loved, and respected by others and by her or his self. Self-esteem allows people to face life with more confidence, benevolence, and optimism, and thus easily reach their goals and self-actualize. Low self-esteem, on the other hand, is said to result from various factors, including genetic factors, physical appearance or weight, mental health issues, socioeconomic status, peer pressure, or bullying (Jones 2003).

In the branding literatures, low self-esteem is gaining increased interest. Recent research in branding suggests that people with low self-esteem tend to show a deep attachment to ‘horizontal’ (similar to others) brands when they feel socially excluded (Dommer et al. 2013). These horizontal brand users, according to these researchers, represent a subgroup within the reference group, allowing an individual to distinguish him/herself from the average group member while creating or maintaining allegiance with the overall group (Mateo 2013). Thus, ‘horizontal’ brands allow people to protect themselves against the sense of exclusion by perceiving the group as made up of many heterogeneous subgroups. By contrast, when these same people with low self-esteem feel included in the group, they often go for ‘vertical’ (differentiated) brands, which enable them to raise their profile, while continuing to belong. ‘Vertical’ brand differentiation occurs when people use brands to demonstrate a degree of superiority over others in the reference group, such as the use of luxury brands. They explain that when people look to adopt brands, which differentiate them, what they might actually be doing is trying to fit in rather than stand out. However these seemingly rather black-and-white differentiations serves as a useful basis for understanding the role of self-esteem in brand choice, and subsequent, for developing more sophisticated assessments of consumer behavior.

3.3 Self-congruity

Scholars hold that consumers tend to prefer brands with images that match their own self-concept (Sirgy 1980), and self-congruence is referred to as this process of matching (Sirgy and Su 2000). In a competitive environment, the extent of the congruence between consumers’ self-concept and a brand’s image significantly influence on consumers’ evaluation, and subsequent choice of the brand (Graeff 1996). Thus, consumers have a positive attitude and buying intentions towards brands that are consistent with their self-image (Argyriou and Melewar 2011; Graeff 1996). Researchers use self-concept to explain consumer behavior (Quester et al. 2000) because a person’s specific behavior patterns are frequently determined by the image that he/she has about himself/herself (Onkvisit and Shaw 1987). This, in turn, suggests that self-congruence play an important element in creating positive brand attitudes (Ekinci and Riley 2003), and influences brand preference (Jamal and Goode 2001) due to its matching process.

Self-concept congruence creates strong emotional attachments between consumers and brands, similar to those between friends and family (Hwang and Kandampully 2012). Intense cases of this can be classified as ‘brand love’ (Ismail and Spinelli 2012), which has been shown to increase consumers’ loyalty to a brand , create positive word of mouth (Carroll and Ahuvia 2006), and allow the charging of a price-premium (Thomson et al. 2005). Such congruence is inextricably linked to connections between the self and the brand. Brand-self connections or sometimes, self-brand connections (SBC), are similar to the concept of consumer-brand identification (CBI) (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Escalas 2004). SBC refers to the degree to which a brand encapsulates the consumer’s self-concept (Escalas and Bettman 2003). CBI refers to the perceived state of oneness between consumer and brand (Stokburger-Sauer et al. 2012). Both are integral parts of the concept of brand attachment. As attachment theory expands in both depth and scope (Ferraro et al. 2011), recent research add the notion of brand prominence, suggesting the connection between consumers’ self and the brand through perceived ease and frequency, brought into consumers’ minds (Park et al. 2010). Brand awareness is related to the strength of the brand in the minds of consumers. It enables consumers to recognize and recall the brand, thus, enhancing brand equity (Keller 1993). Brand awareness is an important goal of marketing efforts because brand image and brand attitude cannot be formed in its absence (Macdonald and Sharp 2003). Some researchers highlight, in particular, the importance of brand awareness in the service context (e.g., Krishnan and Hartline 2001; Prasad and Dev 2000; Kayaman and Arasli 2007), suggesting its importance in the awareness of self-congruence and consumer-brand fit. Brand awareness is linked to brand name; it denotes the probability that a particular brand name comes to the consumer’s mind when choosing a brand (Keller 1993). A well-known brand name serves to reduce the risks of buying and consuming a service brand (Bhradwaj et al. 1993). Furthermore, brand awareness is related to positive outcomes such as brand reputation (Maltz 1991; Sarstedt et al. 2013). Brand awareness and brand association are considered to be the main components of reputation (Gains-Ross 1997; Davies and Miles 1998), and investments in brand awareness can lead to sustainable competitive advantage and long-term brand value (Macdonald and Sharp 2003). Thus, the first step to successfully develop congruence or consumer-brand fit is to understand branding and its related components since they are all linked intricately. This is particularly true when developing brand personalities.

3.4 Brand Personality

Brand personality is a set of human characteristics associated with a brand and carries the symbolic meanings, which the brand represents (Aaker 1997). In turn, these meanings can positively influence the consumers’ brand preferences, and subsequent purchase intentions (Punjatoya 2011). Brand personality is thus defined as the symbolic meaning to a brand (Das et al. 2012). Brand personality allows consumers to identify their self, their ideal self, or other dimensions of self, through the connection to a brand (Belk 1988; Kleine et al. 1995; Malhotra 1988). Brand personality is developed through the personality traits linked to the brand (Aaker 1997) and can ensure differentiation in product categories where intrinsic cues are very similar (Freling and Forbes 2005). When consumers strongly identify with a brand, more time and money will be spent upon it. With regular interaction, long lasting consumer-brand relationships and increased purchases are evident (Carlson et al. 2009). Punjatoya (2011) suggests that people prefer brands with which they share personality characteristics. Aaker (1997) identified five of these characteristics, or dimensions, of brand personality, which are sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Each of these dimensions include sub-dimensions, as follows: down-to-earth, honest, wholesome, cheerful (sincerity), daring, spirited, imaginative, up-to-date (excitement), reliable, intelligent, successful (competence), upper class, sophistication, outdoorsy and tough (ruggedness) (Aaker 1997, Punjatoya 2011). Each describes a specific brand personality trait.

If a brand were to adopt any of the five personality traits, it can encourage an emotional connection with a consumer towards a brand . This is particularly helpful when the consumer is attracted to that particular attribute when electing preferred brands and products. These attributes can be portrayed in the brand values of the company, the product it sells, and the advertising campaigns that it creates. Aaker (1997) suggests that situational factors, such as the advertising campaigns, the individual’s personality, and the personality of a brand, affect the consumer preference toward a brand, which in turn, increases the likeability of a brand (Nguyen et al. 2013a), and the usage of a product (Sirgy 1982). Rayman (2012) investigated the effects of a brand’s advertising campaign on consumers, and conclude that these campaigns encourage positive feelings towards a brand, which helps to persuade consumers to buy products that are related to that brand. Obermiller and Sawyer (2011) demonstrate that by including detailed contextual cues in advertising, and arranging and designing these to induce positive feelings towards a brand, consumers’ emotions are influenced, leading to purchase. These cues include backgrounds to advertisements, brand name, symbols, ad photo, products, etc., and enable consumers to look more favorably towards one brand over another, creating brand preferences, likeable products, and purchase. In combination, these cues make up aspects of the brand’s personality.

An underlying motivation between consumers’ self and brand personality is the concept of emotional attachment. While the benefits of emotional attachment are clear, some times emotional attachment to a brand can also create a consumer confirmation bias. Studies show that consumers are more likely to seek information that confirms their beliefs rather than considering evidence that contradicts them. This notion contains bias, which may influence decision-making among both consumers and marketers. For example, investors often hold on to stocks in a falling market, believing that the markets will rise, without any empirical evidence that this is likely to happen (Mascarenhas 2009). This is similar with consumers’ confidence and their purchase behavior. If consumers believe the recession will last longer then, it will, because they are likely to scale back their spending because of a “confirmation bias.” In a similar line of reasoning, consumers may often not know what they want and desire next, so they rely on a “confirmation bias” about their preferences. Research, investigating consumers’ initial belief and their natural tendency, show that consumers subconsciously remember the preferred information (Cunniffe and Sng 2012). Marketers therefore need to evaluate the reasons why consumers might prefer their brand in light of a cognitive bias, as it creates a powerful predictor of future behavior (Merakovsky 2012).

In other words, confirmation bias contaminates the thinking of consumers’ brand preferences. This is why the brand personality concept is so effective, as consumers often respond to a preferred personality trait, including that of the brands’ personality. While some scholars reveal that consumers feel overwhelmed with communication from brands (Merakovsky 2012), others argue that the ability to verify the confirmation basis is becoming less complex, due to the increased use of social media for consumers to express opinions regarding brands . The majority of the information released through these platforms is a positive nature (Cunniffe and Sng 2012), thus influencing their beliefs. To overcome the confirmation bias, scholars posit that specific characteristics attached to a brand will have an effect on the consumer, based on the notion that ‘people respond to people’. For example, studies show that likeability, an intrinsic human trait, is directly related to emotional connections shared between a brand with its audience, creating what can only be described as the human factor to a brand (Brunner and Emery 2009). Thus, brands that have a likeable personality become meaningful to the consumer, and will impact on consumers’ purchasing behavior, as consumers ‘feel’ something for the brand they are buying into. If consumers see traits within brands that they see in people, such as feelings of happiness, sadness, anger, and excitement, then this will influence their buying habits (Biel 1993). Consequently, when marketers utilize strategies and tactics to induce feelings in order to aid consumers’ decision-making process, they will have an advantage. This process demonstrates the importance of brand personality in branding (Cheverton 2006, p. 28). These human characteristics, constituting the brand personality, allow the consumer to link their own personality traits to the brand , which creates a desire and affect for the brand, which are then to be used by the consumers to express themselves. However, this self-expression is dependent on both the brands’ and the consumers’ traits and personalities being similar. If consumers’ personality is more congruent with a brands personality, it is likely to cause a more positive evaluation of the products’ quality and a higher level of preference for that specific brand (Erdogmus and Büdeyri-Turan 2012).

Psychological research suggests that human personality attributes can be categorized into the ‘Big 5’ dimensions. These include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness (McCrae and Costa 1987). Using these personality attributes brands increasingly build up an image and personality (Evanschitzky et al. 2012) in order to differentiate from competitors (Phau and Lau 2001), and to create a ‘face’ and ‘voice’. Similar to people relations, consumers desire brands with which they share common traits (Aaker 1996). This is achieved through their self-concept, which consists, as discussed earlier, of the actual self (who I am), ideal self (who I want to be), and ought or ideal social self (how I want to be seen) (Sirgy 1982). Brands are well-liked if they fit one of these concepts or disliked if they do not (Rhee and Johnson 2012). Researchers show that successful implementation of the brand personality concept can create positive marketing outcomes, such as positive consumer attitudes, purchase intentions, post purchase satisfaction, and brand loyalty (Jamal and Goode 2001). Having a brand personality that consumers are congruent with may be a key determinant of brand success (Lin 2010; Rhee and Johnson 2012). This highlights the potential impacts that emotional attachments have on consumers’ behavior. Favorable brand personalities increase consumer emotions towards a brand, which increases loyalty, and more importantly, the level of trust (Freling and Forbes 2005). Such trust is essential in todays branding efforts, across all phases of the consumer decision-making process, including the pre- and post-transaction customer experience (Goessens et al. 1999). Table 3.1 shows a summary of the important concepts in this chapter.

4 Luxury Brands

Luxurious goods have become an interesting subject that has been intensively debated and investigated. Because of the improvement of living standards and the changes in social environments and economic developments, more and more consumers can afford luxurious goods and are willingly paying higher amount of money for luxury products these days (Husic and Cicic 2009). Many scholars have underlined luxury brands as products that bring respect to the possessor, apart from the practical value (Grossman and Sharpiro 1988; Deeter-Schmelz et al. 1995). Seringhaus (2005) reports that Dubois and Laurent (1996) posited the existence of a new segment of luxury consumers between the ‘excluded’ and the ‘affluent’. This segment is defined as ‘Excursionists’, joining the traditional ‘Old Money’ (Aldrich 1988) and ‘Nouveau Riches’ (LaBarbera 1988), each having different motivations to pursue the acquisition of luxury products.

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between luxury brands and the self and purchasing behavior of prestige-seeking people (Vigneron 1999; Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie 2006). These studies suggest that the global luxury market contains nine segments (e.g., luxury cruises, designer furniture, fine food, find wine and spirits, Yachts and Private jets) with luxury cars, personal luxury goods and luxury hospitality as the top three segments in comparison to the other segments (D’Arpizio et al. 2014). In Bain and Co.’s report of Luxury Good Worldwide Market Study (D’Arpizio et al. 2014) underlines that the global luxury market is continuously growing and exceeded £630 billion in 2014. The figures also reflect the rising growth of 7 % of the overall luxury market from the previous year. The luxury markets of Americas, Europe, Japan, and the Rise of Asia (including Greater China) will continue to grow across most luxury categories with especially luxury goods and accessories as dominating most of the growth (Nguyen et al. 2016). Furthermore, consumers’ shopping experience and environment has gradually concealed more than 50 % of the market. Luxury brands are significantly connected with the consumers’ self (Kapferer 2006) and the relationships of luxury brands and the three characteristics of self remain critical to understand consumers’ behaviour and decision making (Meffert and Lasslop 2003; Büttner et al. 2006). For example, by understanding how the brand can be viewed as an personality and identity of a company or product (Kotler et al. 2009) and how it is formed in the consumers’ minds (Esch 2010), marketers can develop strategies that influence the target consumers’ ideal self.

The most common characteristics of luxury brands are: exclusiveness, uniqueness, rarity, premium price, excellent quality and design (Nueno and Quelch 1998; Vigneron and Johnson 2004; Mortelmans 2005; Chevalier and Mazzalovo 2008). Linking these ‘personality’ traits to the self-concept can make the consumers choose their brands based on the psychology discussed in this chapter. Though some scholars classify luxury brands based on the functionalities (e.g., expressive and impressive) and other features (Kapferer and Bastien 2009; Truong et al. 2009; Truong 2010), the influential characteristics of luxury brands remain unchanged (e.g., exclusivity, quality, and design). Therefore, these same characteristics can be applied to different self-concepts, ultimately, creating a stronger self-congruence and brand loyalty.

5 Towards the Future of Luxury Consumption—Outcomes of Brand Personality

This section identifies where the brand personality literature is moving and the key areas of research needed in this area. Once the brand successfully creates a personality among its customers, researching the outcomes of brand personality is critical to understanding the benefits of the concept (Melewar and Nguyen 2015). By linking the brand personality concept to other related branding concepts, brand managers are presented with an indication of both positive and negative outcomes that may arise. For example, personal traits of a brand create more intimate relationships through several cues such as brand identity, image, and interaction with the brand (Aaker 1996; Melewar and Karaosmanoglu 2006). Brands personality traits can increase likeability (Nguyen et al. 2013b). If an individual desire a brand personality, it forms an expression and creates brand loyalty (Phau and Lau 2001). Therefore, is it essential for a brand to understand elements that increase the positive outcomes (Yvert-blanchet and Fournier 2007). However, a brand personality may also affect the consumer negatively and their intentions to purchase. Anti-branding and the dark sides of branding are increasing in both depth and scope. Next, the chapter briefly summarizes two key outcomes of brand personality, which are gaining increased interest, namely brand likeability and anti-branding.

5.1 Brand Likeability

Aaker (1997) suggests that brand personality consists of various components, which help to shape the consumers’ impression of a brand. A brand personality is defined as the facade of a brand that sometimes shares human qualities such as friendliness. Recent research suggests that brand likeability is one of these components and such human quality (Nguyen et al. 2015). Brand likeability is defined as “the degree of perceived appeal a customer has for a brand” (Nguyen et al. 2013a, p. 16). The appeal and fondness for a particular brand is often centered in the foundation of the customer and brand relationship (Batra et al. 2012). Emerging brand likeability research further suggest that brand likeability contributes to the overall brand personality concept (Aaker 1997; Lee 2013) and enhances more long-term consumer-brand relationships (Schmitt 2013), considered as vital in this interactive market (Santos-Vijande et al. 2013). It is particularly a priority for firms, focusing on a positive brand image (Romaniuk 2013) and brand reputation (Akdeniz et al. 2013). Continued research reveals that likeability is a cognitive process that preludes important outcomes such as brand attachment (Park et al. 2010), brand love (Batra et al. 2012), and brand satisfaction (Fornell et al. 2010), and used to evaluate the quality of consumer-brand relationships (Lam et al. 2013; Park et al. 2010).

Various conceptualizations are developed and adapted from psychology to explain the occurrence of likeability. Each approach tends to address a specific reason for likeability. For example, the source attractiveness model emphasizes the similarity, familiarity, and likeability of a source such as a firm or a brand (McGuire 1985). The source credibility model emphasizes the importance of a credible and trustworthy source in an exchange relationship (Hovland and Weiss 1951). Similarly, customer satisfaction theories are often used to determine likeability because of the close association with customer preferences, which is explained by the underlying factor of attractiveness (Kano 1984). This is in accordance with the source attractiveness theory and the Kano model of customer preferences (Kano 1984). Satisfaction is different from likeability, though, in that satisfaction is a post-experience measure (Ekinci et al. 2008), which is a condition that is not necessary for likeability to occur. In the past, marketers have emphasized the importance of likeability in the advertising (Yilmaz et al. 2011), customer experiences (Helkkula et al. 2012), and consumer decision-making models, such as the model of buyer readiness states and hierarchy of effects model (Lavidge and Steiner 1961).

Surprisingly, little attention has been given to the concept of brand likeability in a luxury context with links to the brand personality concept. Therefore, the authors consider that the brand likeability concept is an excellent area to further the research on luxury consumption , brand likeability and personality. The brand has an individual personal quality and associations that are reflected in customers’ own personality and values. Building a strong brand personality is essential to building a long-term customer relationship. Thus, brand likeability may be the critical intervening mechanism that connects luxury consumers and brands in more intimate relations that are beyond those of today. The more consumers identify themselves with a brand, the more time, effort, and money they will spend on the products that the brands offer. We thus call for more research into this phenomenon.

5.2 Anti-brand Action

When a relationship with a brand that is highly self-relevant comes to an end, consumers develop anti-brand actions (Johnson et al. 2011). Japutra et al. (2014) argue that self-as consumers incur conscious emotions, anti-brand actions occur when the relationships deteriorate, either because of incongruity of values and/or misuse of trust. In the study of brand attachment, the occurrence of anti-branding is gaining increased attention. Brand attachment is considered a key requisite in consumer-brand relationships that create favorable consumer behaviors such as positive brand attitudes and brand loyalty. The brand attachment concept has many facets similar to brand loyalty, however, researchers note that the two are different, as brand loyalty neglect facets of affective components, such as passion and self-connection (Fournier 1998). Recently, researchers examine the detrimental outcomes of brand attachment by developing a conceptual framework that explores how brand attachment may explain detrimental consumer behaviors , such as oppositional brand loyalty and anti-brand actions (Japutra et al. 2014). By including consumers’ trash-talking and Schadenfreude in brand communities and their subsequent outcomes, these researchers reveal that the link between brand attachment and oppositional brand loyalty is driven by consumers’ social identity and sense of rivalries. Furthermore, they put forward that brand attachment leads to anti-brand actions when relationships deteriorate. Scholars identify two factors behind the deterioration: (1) companies’ opportunism activities, and (2) incongruity between consumers’ values with the brand.

Oppositional brand loyalty is driven by consumers’ social identity, which is characterized by: (1) self-categorization, (2) affective commitment, and (3) group-based self-esteem (Bergami and Bagozzi 2000). Because consumers display strong attachment with the brand, it reflects their self-categorization and affective commitment, causing oppositional brand loyalty to occur (Muniz and O’Guinn 2001). Emotional feelings such as love, hate, pity, and anger provide the energy that stimulates and sustains a particular attitude towards a brand (Wright 2006). That is, consumption is governed by consumers’ feelings and emotions, in addition to the functional aspect of the product (Zohra 2011). Hence, researchers direct much attention towards the affective factors in marketing (Keller 1998). Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001, p. 82) define brand affect, as “a brand’s potential to elicit a positive emotional response in the average consumer as a result of its use.” Evoking consumer emotions is a major factor for developing a long-term relationship between a luxury consumer and a brand (Zohra 2011), yet little research has been conducted in this area. Behavior decision theorists investigate affective reactions that influence the decision-making process (Garbariono and Edell 1997). Consumer satisfaction and purchase intention are directly influenced by positive affects (Oliver et al. 1997). Yu and Dean (2001) propose that the affective element of consumer satisfaction is a better component for predicting positive word-of-mouth than cognitive elements (e.g. price and quality). Consequently, a brand that forms a positive emotional relationship with the consumer gains a competitive advantage while those that induce anti-branding develop a competitive dis-advantage (Nowak et al. 2006). As a topic that is gaining increased interests, surprisingly, little research is dedicated towards linking luxury consumption and anti-branding. Therefore, we call for expansive research into this very interesting area.

6 Practicing Marketing : Cases Using the Self-concept and Brand Personality

This following section explains how the theory and literature findings on the chapter topic can be applied in practice. A number of examples/illustrations/mini-cases are provided. The iconography of luxury fashion labels representing status claims that the perception of status from displaying luxury is due to its exclusivity and premium price (Baugh and Davis 1989). The findings of Nia and Zachjowsky’s study (2000) suggest that consumers consider that the ownership of original luxury branded products provides them with both personal satisfaction and, most importantly, the wider social satisfaction derived from being admired, recognized and accepted by others. De Chertatony (2010) outlines the importance of how the personality of a brand says something about the consumer, suggesting that people are more likely to think favorably towards a brand if it represents values that they as individuals hold true to themselves. Till (1998) creates associations between Pepsi and young people and notes the importance of the use of celebrity endorsements to create a brand personality that interacts with this group of consumers. Pepsi is known to use endorsements from footballers, such as Frank Lampard and Lionel Messi. According to Till (1998), the endorsements like footballers are hugely beneficial, as consumers make associations with the celebrity and the product. This association creates a desire for the brand, leading to purchase. De Chernatony (2010) suggests that such effect on the consumers’ self creates a long lasting success to a brand due to the consumers’ needs to connect with the brand itself.

Lazarevic (2012) highlights that congruency with the brand is an important aspect of building a brand based on celebrity endorsement. The celebrity must be an excellent fit with the brand personality characteristics with that of the consumers’ self. By using a celebrity endorser, brands allow the consumer to identify with the brand and, once successfully implemented, wanting to adopt the brands’ image and lifestyle, which the brand and the celebrity represents (Jain et al. 2011). Such representations are vital for marketers to consider, as these traits create either a positive or negative attitude towards that brand (Spry et al. 2011). If the brand is seen as favorable, the brand becomes more likeable to the consumer, as they base their perceptions on the celebrity endorser as a likeable figure themselves (Lazarevic 2012).

Another example of the importance of congruence is found in the luxury fashion and foodservice industries that include restaurants, luxury consumers, and fashion leaders (e.g., Han et al. 2015). For example, scholars suggest that self-congruence is one of the main factors that influence a restaurant visit. Restaurants are places for dining, social meetings, and business. Hence, the image of a restaurant (e.g., interior design, music, menu, and staff dress, and behavior) must match the self-concept of its target consumers. The same notion can be applied to luxury brand and fashion brands. Symbolic trademarks, artistic designed pieces, well-presented designers, and collectable product collections are the key features to associate with luxury brands and consumers. Luxury consumers are more likely to purchase a product or choose a brand that fit with his/her personality, identity, and image to fulfill their personal possessions.

In practice, shoppers’ decision-making styles and their eventual consumer behavior may vary according to differences in the kinds of goods and services they need or want (Bellenger and Korgaonkar 1980; Hiu et al. 2001). Sproles and Kendall (1986) asserted that “a person does not follow one decision-making style in all shopping decision” (p. 286), signifying that many consumers implement two or more approaches to making choices, but Wesley et al. (2006) found that they seldom make use of all the styles proposed as being theoretically available in the literature of purchasing behavior studies. Observed differences in consumers’ buying behavior will be attributable to cultural differences (Durvasula et al. 1993).

The following section will apply three examples to underline the relationship between self-concept and brand personality and how luxury consumers’ decision making process get influenced by the effects of self. Three examples: Net-A-Porter, Burberry and Innocent will be discussed in the following section to underline the relationship between brands and self-concept in terms of consumer’s decision making process.

6.1 ELuxury Store—Net-A-Porter

Net-A-Porter, an eLuxury online store established in June 2000, has become one of the leading e-Stores for luxury brands due to the higher rate of consumers’ repeat purchases, consumer loyalty, and satisfaction (Smith 2014). Net-A-Porter represents numerous luxury brands as their online outlet store and advertises itself on many leading fashion and luxury magazines. It fulfills many luxury fashion consumers’ needs in terms of luxury services, products, and compatible prices on an aggregated platform and thus carries popular product lines and collections to fulfill consumers’ demands . With to the development of online technology, and its dramatic influence on our lifestyles, their success has been to open up a channel for the young luxury consumers. By targeting a rising luxury segment successfully, Net-A-Porter has affected the traditional luxury market by increasing luxury purchases online (Choo et al. 2012).

6.2 Luxury Brand—Burberry

Many luxury retailers are now utilizing online technology to enhance their performance in virtual environments. Burberry has taken the luxury fashion industry into a new retail era by adapting the eStore user experience and design concept and applied these to a brick-and-mortar environment. Burberry generated a lot of attention and became an eLuxury pioneer by demonstrating its latest fashion and brand image via multiple marketing channels to boost their sales and generate consumers’ interests. In 2015, Burberry had over 17 million Facebook ‘Likes’ and 5 million Twitter followers. These figures have been increasing by 33 % since 2013. Burberry’s brand personality and image are perceived as being friendly, and their luxury products are purchased based on associations of likability, trustworthiness, and credibility. As discussed above, to create an excellent consumer purchasing journey, a brand must highlight the luxury brands’ value and underline how self-esteem can be created by developing congruity such that the consumers can associate themselves with the chosen brand. Such self-congruity will appeal to luxury consumers due to the ‘self-brand personality’ link. An important aspect of Burberry’s success-story is the brand’s ability to stay consistent in all their marketing activities across the latest technologies (e.g., smart device, mobile application, and social media). This consistency is reflected in their brand performance and overall positive associations among consumers. For example, many leading fashion brands have now adopted the concept of ‘magic mirror’ (e.g., the idea to help consumers receive full service by utilizing digital and smart devices from the moment consumers arrive in the store to the selection of clothing, fitting facility, and assistance). Such smart activities have enhanced consumers’ purchasing experience during their decision making process.

6.3 Luxury and Healthy Diet—Innocent Drink

Innocent—a green business and beverage brand—encourages a healthy lifestyle that is enriched by delicious smoothies, juices, and vegetable pots (Innocent 2012). As a higher-end beverage, the Innocent drinks are offered at a price premium; however, consumers find the benefits of the healthy ingredients, namely, nutrients, vitamin C, fibers, and antioxidants, to largely make up for the premium price. Innocent positions itself as the leading smoothie brand with a 65 % market share in the UK (Datamonitor 2010). Their success is due to the publics’ rising concern to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Moreover, their quirky and creative design that typically include colorful schemes, pictures, and fun messages, both on the packaging and their website, appeal to the health conscious consumers. Innocents’ brand personality and image are perceived as being friendly, and the drinks are purchased based on associations of trustworthiness and credibility. An important aspect of Innocent’s success-story is the brand’s ability to stay consistent in all their marketing activities and in their brand identity. Innocent’s recyclable bottles, the ingredients they use, and the name ‘Innocent’ itself help to confirm their brand image as an eco friendly, likeable brand (Miller 2010). By integrating these core values into everything Innocent does, the brand personality , image, and concept successfully appeals to their target consumers (Lange and Dahlén 2003). Younger consumers prefer brands that make them feel good about themselves. Innocent meets this claim by being authentic. For example, they convey their limitations in an honest and transparent manner. In their packaging, some bottles have a relatively low recycle level, so to overcome any criticism, Innocent recently printed the statement ‘but we’re trying’ on the bottles. Implementing such a gesture enabled consumers to make continued associations of a brand that is aware of their environmental responsibilities.

Features like this create positive goodwill to the brand , which ultimately determine whether the consumer will consider purchasing the product or not. Scholars believe that a likeable brand has global positive associations that incorporate emotional elements (Nguyen et al. 2013a). If an advertisement proves to be appealing to the audience, it is more likely to achieve a high amount of awareness and future positive associations. One aspect that proves to have a significant effect on likeable brands and advertisements is the authenticity of human traits through the brand’s personality (Yuan et al. 2014). Another important effect that appeals to the audience is relatable experiences that create familiarity such as the use of symbolism and characters within an advertisement.

Alreck and Settle (1999) presents a framework to create and establish strong bonds between consumers and brands. This framework consists of six strategic stages, namely, that a brand has to: (1) be linked to a particular consumer need, (2) create a positive atmosphere, (3) attempt to have an appeal connected to consumers’ attitude, (4) guide consumers and introduce rewards in exchange for brand preference, (5) penetrate perceptual barriers in order to influence the consumer’s decision-making process, and (6) create a brand, product or service, which consumers are eager to purchase. It seems that Innocent has been very successful across all of these stages. Kim (1990) suggests that a brand in itself is not a tangible object, but an object within the mind of the consumer. A brand is merely the identity of a product, service or process, which is distinguished by certain characteristics, such as feature, benefit, name, logo, design , and perhaps most importantly a personality. A brand can represent certain meanings, values, and include a social role of the organization. Innocent’s combination of all these characteristics has generated competitive advantages relative to competitors, and aligned their values with stakeholders, advocates, and customers.

7 Conclusion

This chapter considered how the self-concept and brand personality influence luxury consumers’ purchasing decisions. It explored the person-specific, internal or external attributes that interact to form one’s self-concept, including theories on self-concept, self-esteem, congruity, and brand personality. The key to understanding luxury consumers’ decision making including their purchases comes down to the value that is associated with the brand and how an individual links his or her self with those values. According to Keller (1998) branding is about adding intangible value to a brand through various marketing efforts. Branding is about differentiating one organization from another in order to create a sustainable competitive advantage (Hollis 2011). A brand personality is such a differentiated brand. As technology increasingly determine the way in which humanity communicates and build relationships, it will be more important for companies to have a personality, face, and a voice—to engage with customers at the same level and to stand out. Furthermore, shopping activities carry significant value, and consuming experience are covering a wilder range of the areas such as purchasing experience, shopping environment—merchandise layout and store atmosphere, and other relevant factors (Miller et al. 1998; Sherry 1998, 1990; Woodruffe-Burton et al. 2002). Research suggests that a friendly, happy, and pleasant person will be more popular, successful, and trustworthy. A firm must therefore adopt the concept of brand personality to build closer relationships. The difference between various companies will be the way in which they differ in their personalities. However, to achieve a consumer-brand match, or congruence, firms must consider both the brand personality and the consumer psychological concepts and motivation, including self-guides and self-esteem in order to understand luxury consumers better. For marketers, more research must be done in terms of examining how the self is influenced by increased efforts by luxury brands to create a personality with a face and voice in order to be more attractive and likeable. Failure to understand the underlying psychological underpinnings may cause distress, negative emotions, and anti-brand behavior, damaging the brand.

7.1 Further Investigation

Key questions/projects relevant to the topic of self and brand personality:

-

1.

What are the benefits of a brand personality—both to the enterprise and to the customer?

-

2.

Describe why a brand personality needs to be an enterprise-wide strategy. How would it affect each of these principal business functions? (1) Financial, (2) Production and logistics (3) Marketing communications and interaction, and customer service, (4) Distribution and channel management, and (5) Organizational management strategy.

-

3.

If brand personality is such a good idea, why didn’t companies operate from the perspective of building personalities 50 years ago?

-

4.

In the age of information and interactivity, what will happen to branding and brand personality?

-

5.

Is brand personality relevant for the owner of a hotdog stand? In which way?

-

6.

Develop brand personalities for these product categories: Luxury automobiles (consumer), First class air transportation, Five star hotel rooms, Luxury cosmetics, Computer software (B2B), Pet food, Refrigerators, Strawberries.

-

7.

What can firms do to better understand luxury customers’ self? How might firms use this information to their benefit?

-

8.

Imagine you have been assigned to change a luxury product-oriented company to a luxury brand-oriented firm. What is the first thing you do? What is your road map for the next 2–5 years?

References

Aaker DA (1996) Building strong brands, 1st edn. The Free Press, New York

Aaker JL (1997) Dimensions of brand personality. J Mark Res 34(6):347–356

Adams JS (1965) Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L (ed.) Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press, New York

Akdeniz B, Calantone RJ, Voorhees CM (2013) Effectiveness of marketing cues on consumer perceptions of quality: the moderating roles of brand reputation and third-party information. Psychol Market 30(1):76–89

Aldrich JR (1988) Chemical ecology of heteropetra. Ann Rev Entomol 33:211–238

Alreck PL, Settle RB (1999) Strategies for building consumer brand preference. J Prod Brand Manag 8(3):130–144

Argyriou E, Melewar TC (2011) Consumer attitudes revisited: a review of attitude theory in marketing research. Int J Manag Rev 13:431–451

Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM (1991) Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol 61:226–244

Batra R, Ahuvia A, Bagozzi RP (2012) Brand love. J Market 76(2):1–16

Baugh DF, Davis LL (1989) The effect of store image on consumers’ perceptions of designer and private label clothing. Clothing Text Res J 7(3):15–21

Baumeister RF, Smart L, Boden JM (1996) Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: the dark side of high self-esteem. Psychol Rev 103(1):5–33

Belk RW (1988) Possessions and the extended self. J Consum Res 15:139–168

Bellenger DN, Korgaonkar PK (1980) Profiling the recreational shopper. J Retail 56:77–92 Fall

Bergami M, Bagozzi RP (2000) Self-categorization, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. Br J Soc Psychol 39(4):555–577

Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2003) Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J Market 67(2):76–88

Bhradwaj SG, Varadarajan RP, Fahy J (1993) Sustainable competitive advantage in service industries: A conceptual model and research propositions. J Market 57:83–99

Biel AL (1993) Converting image into equity. In: Aaker D, Biel A (eds) Brand equity and advertising: advertising’s role in building strong brands. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Hillsdale, pp 67–82

Bowlby J (1973) Attachment and loss. In: Separation, vol 2. Basic Books, New York

Branden N (1994) The six pillars of self-esteem. Bantam Books, New York

Brunner R, Emery S (2009) Design matters: how great design will make people love your company. Financial Times Prentice Hall, Harlow

Büttner M, Huber F, Regier S, Vollhardt K (2006) Phänomen Luxusmarke. Gabler Verlag, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, Wiesbaden

Carlson BD, Donavan DT, Cumiskey KJ (2009) Consumer-brand relationships in sport: brand personality and identification. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 37(4):370–385

Carroll BA, Ahuvia AC (2006) Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Market Lett 17(2):79–90

Chaudhuri A, Holbrook MB (2001) The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J Market 65(2):81–93

Chevalier M, Mazzalovo G (2008) Luxury brand management: a world of privilege. Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey

Cheverton P (2006) Understanding brands. Kogan Page, London

Choo HJ, Moon H, Kim H, Yoon N (2012) Luxury customer value. J Fashion Market Manage: Int J 16(1):81–101

Cooper A, Simmons P (1997) Brand equity lifestage: an entrepreneurial revolution. TBWA Simmons Palmer. Unpublished working paper

Corneo C, Jeanne O (1997) Conspicuous consumption, snobbism and conformism. J Public Econ 66:57–71

Cunniffe N, Sng M (2012) Brand loyalty: conformation bias. Admap, February 2012

D’Arpizio C, Levato F, Zito D, de Montgolfier J (2014) Luxury goods worldwide market study fall-winter 2014—the rise of the borderless consumer. Bain & Co. (Online) Retrieved from: http://www.bain.com/bainweb/PDFs/Bain_Worldwide_Luxury_Goods_Report_2014.pdf. Accessed 4th Dec 2015

Das G, Guin KK, Ditta B (2012) Developing brand personality scales: a literature review. IUP J Brand Manage IX(2):44–63

Datamonitor (2010) Innocent drinks case study: capitalising on the health trend in the smoothie category. Datamonitor:1–15

Davies G, Miles L (1998) Reputation management: theory versus practice. Corp Reputation Rev 2(1):16–27

De Chertatony L (2010) From brand vision to brand evaluation the strategic process of growing and strengthening brands, 3rd edn. Taylor and Francis

Deeter-Schmelz D, Dawn R, Moore J, Goebel D, Solomon P (1995) Measuring the prestige profiles of consumers: a preliminary report of the PRECON scale. In: Engelland B, and Smart D (eds) Marketing foundations for a changing world: proceedings of the annual meeting of the southern marketing association, Southern Marketing Association, Orlando, FL, pp 395–399

Dittmar H (1994) Material possessions as stereotypes: material images of different socio-economic groups. J Econ Psychol 15(4):561–585

Dolich IJ (1969) Congruence relationships between self-images and product-brands. J Market Res Soc 6:80–84

Dommer SL, Swaminathan V, Ahluwalia R (2013) Using differentiated brands to deflect exclusion and protect inclusion: the moderating role of self-esteem on attachment to differentiated brands. J Consum Res 40:657–675

Dubois B, Laurent G (1996) Le luxe pardelales frontieres: une etude exploratoire dansdouze pays. Decisions Mark 9:35–43

Duma F, Hallier-Willi C, Nguyen B, Melewar TC (2016) The management of luxury brand behavior: adapting luxury brand management to the changing market forces of the 21st century. Market Rev 16(1)

Durvasula S, Lysonki S, Andrews J (1993) Cross cultural generalisability of a scale for profiling consumers decision marketing styles. J Consum Aff 27(1):33–75

Eagley AH, Chaiken S (1993) The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Ekinci Y, Riley M (2003) An investigation of self-concept: actual and ideal self-congruence compared in the context of service evaluation. J Retail Consum Serv 10(4):201–214

Ekinci Y, Massey GR, Dawes PL (2008) An extended model of the antecedents and consequences of consumer satisfaction for hospitality services. Eur J Mark 42(1/2):35–68

Erdoğmuş İ, Büdeyri-Turan I (2012) The role of personality congruence, perceived quality and prestige on ready-to-wear brand loyalty. J Fashion Market Manage 16(4):399–417

Escalas JE (2004) Narrative processing: building consumer connections to brands. J Consum Psychol 14:168–180

Escalas JE, Bettman JR (2003) You are what they eat: the influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. J Consum Psychol 13:339–348

Esch F-R (2010) Strategie und Technik der Markenführung, 6th edn. Vahlen, Munich

Evans M, Jamal A, Foxall G (2012) Consumer behavior, 2nd edn. John Wiley, Chichester

Evanschitzky H, Ramaseshan B, Woisetschläger D, Richelsen V, Blut M, Backhaus C (2012) Consequences of customer loyalty to the loyalty program and to the company. J Acad Mark Sci 40(5):625–638

Ferraro R, Escalas JE, Bettman JR (2011) Our possessions, our selves: domains of self-worth and the possession–self link. J Consum Psychol 21(2):169–177

Festinger L (1957) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Fornell C, Rust R, Dekimpe M (2010) The effect of customer satisfaction on consumer spending growth. J Mark Res 47(1):28–35

Fournier S (1998) Consumers and their brands: developing relationship theory in consumer research. J Consum Res 24(4):343–353

Freling H, Forbes L (2005) An empirical analysis of the brand personality effect. J Prod Brand Manage 14(7):404–413

Gains-Ross L (1997) Leveraging corporate equity. Corp Reputation Rev 1(1/2):51–56

Garbariono EC, Edell JA (1997) Cognitive effort, affect, and choice. J Consum Res 24(2):147–158

Gillath O, Shaver PR, Mikulincer M (2005) An attachment-theoretical approach to compassion and altruism. In: Gilbert P (ed) Compassion: its nature and use in psychotherapy. Brunner-Routledge, London, pp. 121–147

Goessens C, Hoogerbrugge M, Kappert C, Schuring RJ, Vogel M (1999) Brands and advertising. Admap Publications, Henley

Graeff TR (1996) Using promotional messages to manage the effects of brand and self-image on brand evaluations. J Consum Market 13(3):4–18

Grossman GM, Shapiro C (1988) Counterfeit-product trade. Am Econ Rev 78:59–75

Grubb EL, Grathwohl HL (1967) Consumer self-concept, symbolism and market behavior: theoretical approach. J Market 31:22–27

Gupta S, Navare J, Melewar TC (2011) Investigating the implications of business and culture on the behavior of customers of international firms. Ind Mark Manage 40(1):65–77

Hagger MS, Ashford B, Stambulova N (1998) Russian and British children’s physical self-perceptions and physical activity participation. Pediatr Exerc Sci 10:137–152

Han SH, Nguyen B, Lee T (2015) Consumer-based chain restaurant brand equity (CBCRBE), brand reputation, and brand trust. Int J Hospitality Manage 50:84–93

Heider F (1958) The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley, New York

Helkkula A, Kelleher C, Pihlström M (2012) Practices and experiences: challenges and opportunities for value research. J Serv Manage 23(4):554–570

Higgins ET (1987) Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychol Rev 94:319–340

Higgins ET, Roney CJR, Crowe E, Hymes C (1994) Ideal versus ought predilections for approach and avoidance: distinct self-regulatory systems. J Pers Soc Psychol 66:276–286

Hiu ASY, Sui NYM, Wang CCL, Chang LMK (2001) An investigation of decision-making styles of consumers in China. J Consum Aff 35(2):326–345

Hollis N (2011) It is not a choice: brands should seek differentiation and distinctiveness. Millward Brown Point of View: April 2011 WARC

Hovland CI, Weiss W (1951) The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin Q 15(4):635–650

Husic M, Cicic M (2009) Luxury consumption factors. J Fashion Mark Manage 13(2):231–245

Hwang J, Kandampully J (2012) The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships. J Prod Brand Manage 21(2):98–108

Innocent (2012) Innocent drinks (Online) Retrieved from: http://www.innocentdrinks.co.uk/us/our-story. Accessed 7th Nov 2013

Ismail AR, Spinelli G (2012) Effects of brand love, personality and image on word of mouth the case of fashion brands among young consumers. J Fashion Market Manage 16(4):386–398

Jain V, Roy S, Daswani A, Sudha M (2011) What really works for teenagers: human or fictional celebrity? Young Consum: Insight Ideas Responsible Marketers 12(2):171–183

Jamal A, Goode MMH (2001) Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Market Intell Plann 19(7):482–492

Japutra A, Ekinci Y, Simkin L, Nguyen B (2014) The Dark Side of brand attachment: a conceptual framework of brand attachment’s detrimental outcomes and the role of trash-talking and Schadenfreude. Market Rev

Johnson AR, Matear M, Thomson M (2011) A coal in the heart: self-relevance as a post-exit predictor of consumer anti-brand actions. J Consum Res 38(1):108–125

Jones FC (2003) Low self esteem. Chicago Defender. p 33. ISSN 0745-7014

Kano N (1984) Attractive quality and must-be quality (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Qual Control 14(2):39–48

Kansara VA (2011) Digital scorecard amble with Louis Vuitton (Online) Retrieved from: http://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/digital-scorecard/digital-scorecard-amble-with-louis-vuitton. Accessed 10th Dec 2015

Kapferer JN (2006) The two business cultures of luxury brands. In: Schroeder JE, Salzer- Mörling M (eds) Brand culture. New York, pp 67–76

Kapferer JN (2012) The new strategic brand management In: Advanced insights & strategic thinking. Kogan Page Ltd. London, pp 149–177

Kapferer J-N, Bastien V (2009) The specificity of luxury management: turning marketing upside down. J Brand Manage 16(5–6):311–322

Kayaman R, Arasli H (2007) Customer based brand equity: evidence from the hotel industry. Managing Serv Qual 17(1):92–109

Keller KL (1993) Conceptualizing, measuring, managing customer-based brand equity. J Market 57(1):1–22

Keller K (1998) Strategic brand management. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Kim P (1990) A perspective on brands. J Consum Market 7(4):63–67

Kleine SS, Kleine RE III, Allen CT (1995) How is a possession me or not me? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment. J Consum Res 22(3):327–343

Kotler P, Keller K, Brady M, Goodman M, Hansen T (2009) Marketing management. Pearson Education, Harlow

Krishnan BC, Hartline MD (2001) Brand equity: is it more important in services? J Serv Mark 15(5):328–342

LaBarbera PA (1988) The nouveaux riches: conspicuous consumption and the issue of self-fulfillment. In: Hirschman EC (ed) Research in consumer behaviour, vol. 3. JAI Press, Greenwich CT, pp 179–210

Lam S, Ahearne M, Mullins R, Hayati B, Schillewaert N (2013) Exploring the dynamics of antecedents to consumer-brand identification with a new brand. J Acad Mark Sci 41(2):234–252

Lange F, Dahlén M (2003) Let’s be strange: brand familiarity and ad-brand. J Prod Brand Manage 12(7):449–461

Lavidge RJ, Steiner GA (1961) A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. J Market 25(6):59–62

Lazarevic V (2012) Encouraging brand loyalty in fickle generation Y consumers. Young Consum: Insight Ideas Responsible Market 13(1):45–61

Lecky P (1961) Self-consistency: a theory of personality. NY Shoe String Press, New York

Lee E (2013) A prototype of multicomponent brand personality structure: a consumption symbolism approach. Psychol Market 30(2):173–186

Levy SJ (1959) Symbols for sale. Harvard Bus Rev 37(4):117–124

Lin YL (2010) The relationship of consumer personality trait, brand personality and brand loyalty: an empirical study of toys and video games buyers. J Prod Brand Manage 19(1):4–17

Macdonald E, Sharp B (2003) Management perceptions of the importance of brand awareness as an indication of advertising effectiveness. Market Bull 14(2):1–11

Malhotra NK (1988) Self-concept and product choice: an integrated perspective. J Econ Psychol 9(1):1–28

Maltz E (1991) Managing brand equity: a conference summary. Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge pp 99–110

Marsh HW (1990) A multidimensional, hierarchical model of self-concept: theoretical and empirical justification. Educ Psychol Rev 2:77–172

Mascarenhas M (2009) Confirmation bias and brand loyalty. CMA, (Online) Retrieved from: http://www.the-cma.org/about/blog/confirmation-bias-and-brand-loyalty. Accessed 20th Dec 2012

Maslow AH (1987) Motivation and personality, 3rd edn. Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA

Mateo P-M (2013) Self-esteem a central factor in consumers’ brand allegiance. (Online) Retrieved from: http://www.atelier.net/en/trends/articles/self-esteem-central-factor-consumers-brand-allegiance_423657. Accessed 4th Nov 2015

McCrae RR, Costa PT (1987) Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol 52(1):81–90

McGuire WJ (1985) Attitudes and attitude change. In Lindzey G, Aronson E (eds) Handbook of social psychology, random house. New York, pp 233–346

Meffert H, Lasslop I (2003) Luxusmarkenstrategie. In Leipzig

Melewar TC, Karaosmanoglu E (2006) Seven dimensions of corporate identity: A categorisation from the practitioners’ perspectives. Eur J Mark 40(7/8):846–869

Melewar TC, Nguyen B (2015) Five areas to advance branding theory and practice. J Brand Manage 21(9):758–769