Abstract

Improvements in the treatment of cancer have meant that the number of cancer survivors is growing. This group is now more likely to be living with the longer-term adverse effects of cancer on their overall health and wellbeing, and to develop comorbid chronic conditions that require ongoing care in the community, beyond the cancer clinic. People with chronic conditions are also generally living longer due to improvements in treatment, care and support options and therefore are at risk of developing cancer as they age. This chapter outlines a range of chronic condition management models likely to be necessary for effective self-management support to cancer patients and survivors who suffer from and develop chronic conditions, or have risk factors for their development, and people with chronic conditions who also go on to develop cancer. Integrated care and communication issues across healthcare transitions are briefly discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Cancer patients and survivors

- Chronic condition management

- Self-management

- Models of care

- Care coordination

-

Chronic condition management models available to support chronic condition self-management are also relevant to cancer patients and survivors.

-

Integration of care across transitions from acute cancer treatment to longer term care in the community continues to be an issue for cancer patients, despite their high rates of comorbid chronic health conditions.

-

Peer support, nurse-led clinics in primary care, coordinated care across transitions, and chronic condition self-management care planning are some of the range of approaches that show promise for people living with chronic conditions and cancer.

8.1 Introduction

Many people with cancer have coexisting chronic conditions and many cancer survivors subsequently develop them because they share many risk factors and several chronic conditions are causally linked with increased risk of cancer [1]. Therefore, how chronic conditions are managed is very relevant to cancer and together, they pose many challenges to traditional siloed models of care. Cancer in its treatment phase, in the management of co-existing chronic diseases and the increased risk of acquiring chronic diseases as a consequence of treatment, suggests that the concepts and models of care developed for chronic condition management internationally should be applied to cancer management. During the diagnosis and treatment phase of cancer, coping with the stress of the diagnosis, understanding the medical aspects of the condition and the treatment options, and managing the daily impacts of the disease and its treatment are similar to dealing with any chronic disease. The most internationally recognised approach to chronic disease management is the Chronic Care Model [2, 3], an evidenced based framework describing six elements at the health system and the practice level which aim to assist a patient to be activated through the support of a collaborative multidisciplinary team (see below). Like patients with chronic conditions more broadly, the current care provided to cancer patients is often delivered within the specialist silo of the oncology clinic. Their other chronic care needs may become a lesser priority and coordination of treatments and needs across the specialist chronic disease areas can be challenging for all concerned.

With improvements in screening, early detection and treatment of many cancers, survival rates have likewise improved significantly; and the cancer survivorship trajectory has changed significantly [4]. Cancer survivors are simply living longer and are a growing population within the community [5, 6]. This has meant that many cancer survivors must accommodate the management of a number of complicating late effects of cancer and its treatments that can contribute to the development of chronic health conditions. Like other groups in the population, cancer survivors might also have existing chronic conditions that pre-date their cancer diagnosis that also must be managed. Alternatively, and in line with others in the population, cancer survivors might also develop chronic conditions due to hereditary markers for certain conditions, the influence of a range of lifestyle risk factors (such as smoking and low levels of physical activity), and the natural course of aging. Conversely, as more people are living longer due to improvements in medical treatment and care, they are likely to develop a range of comorbid chronic health conditions in older age, including various types of cancers. Together, these circumstances can create a complex and unique picture of comorbidity and risk factors that requires longer-term management across the person’s lifespan. The cancer journey for many people who experience it is recognised as involving a continuum from prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, to end of life care [7]. This change in the cancer survivorship trajectory requires a commensurate change in how both cancer care and chronic condition care in the community are structured and delivered.

Effective management of cancer by health services requires effective integration of care at all stages of disease trajectory and begins with how cancer care providers view their roles and responsibilities in communicating with other stakeholders in care, and how they view the role of cancer patients in care, as either active or passive participants. In the early stages of diagnosis and treatment, doctors are the experts and patients are very dependent on the knowledge and skill of the clinician; however, patients should be engaged as early as possible in their own care through shared decision-making. As the course of treatment evolves, patients should be encouraged to share their knowledge of the condition and its impacts on them, and how they manage the condition and its treatment on a daily basis. Principles of patient centred care should be central to the clinician-patient relationship at all stages of the treatment and management of the condition. Integration of care refers to how health providers take into account other medical and psychiatric co-morbidities, the psychosocial aspects of the patient’s circumstances and how other health providers and community services are integrated into the patient’s care.

Integration of care is also important after treatment is completed, to mitigate the impact of chronic conditions that might develop as a result of the cancer treatment. However, cancer care is usually focused on management of cancer specific issues with less emphasis on management of other health problems [8]. Strategies such as self-management support, which are recognised as effective for the management of other chronic conditions, such as diabetes and arthritis [9, 10], are rarely utilised with cancer patients and cancer survivors. This is despite research confirming the importance of encouraging self-management and patient autonomy for improved outcomes for cancer survivors, and improved quality of life regardless of where the person sits on the cancer trajectory from prevention to palliation [11, 12]. There is also less emphasis on prevention strategies and lifestyle modification for cancer survivors. Chronic condition management is often not considered a priority by cancer care providers or cancer patients as the fear of cancer is considered the immediate priority for treatment and care. Additionally, cancer care providers have limited skills in chronic condition management and self-management support to patients, and health care systems are not always designed to support integrated care of cancer and other chronic conditions [13, 14]. Likewise, general practitioners (GPs) and other health care professionals within primary care may be well-versed at coordinating care for a their patients with a broad range of chronic health conditions though they may be more tentative in providing care to cancer patients during their more acute treatment phase, instead deferring to specialist oncology services [14–16].

This is also so for cancer survivors, once their care moves from the cancer care services to broader community and primary care services where care often occurs within health systems designed to provide episodic, acute health care and fails to address self-management, prevention and health promotion, and to provide sufficiently coordinated systems for follow-up [17]. Current approaches to cancer care do not adequately engage cancer patients in self-management; their focus is on the immediate need to treat the cancer. This is despite emerging evidence that cancer patients can be engaged earlier in their cancer trajectory [18] and longstanding advocacy from consumer support organisations that many cancer patients desire and indeed do undertake a range of activities to build their knowledge and alter their lifestyle in order to help maximize their health outcomes following a cancer diagnosis [14].

Likewise, current approaches do not adequately engage cancer survivors to self-manage their long-term needs, non-cancer issues such as health lifestyle management or management of comorbidity [13, 15, 16]. We know that many cancer survivors continue to have unmet physical and emotional needs within existing models of care [19–21]. Chronic conditions require delivery of a different kind of health care; one that is more holistic and more fully includes the person and their informal supports, and which improves the coordination and communication of care across a range of healthcare providers and, where relevant, psychosocial support providers.

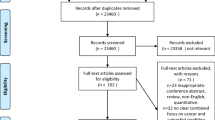

Recognising cancer as a chronic condition requires a shift in how care is provided to these patients. Cure or amelioration of the immediate threat to the person’s life is no longer the only priority. Models of care must now consider and place greater emphasis on the cancer survivor’s active involvement in decisions made about their care, acknowledging their ‘lived experience’ expertise. This is also relevant for patients still in active treatment for their cancer and those people who are receiving palliative care for their cancer and/or other chronic conditions. Because cancer survivors’ care will be delivered largely in the communities in which they live, health professionals and services in the community and primary health services and non-government consumer-engaged organisations now play an even more important role in providing that support and care than previously, when care was predominantly centred around acute care within tertiary hospital oncology departments. This shift has required a commensurate focus on models that emphasise greater patient empowerment, health literacy and self-management; as well as greater coordination of care between health professionals and between services, involving multidisciplinary and interprofessional care, and continuity of care. The acute model of care in which the oncology, respiratory, cardiac or other chronic disease specialist is the primary care provider is no longer the only approach to care that is required. Hence, there has been a growing focus on models of care that involve chronic condition management and self-management support care planning for cancer survivors [14]. These have relevance to cancer patients more broadly, regardless of their stage of treatment, especially if they have other comorbid chronic physical and/or mental health conditions. Cancer patients have different needs at different points in their cancer journey, as the following diagram shows; they move between these care points, according to the stage, severity and complexity of those needs (see Fig. 8.1).

8.2 Chronic Condition Management Models for Cancer Patients and Cancer Survivors

Chronic condition management models of care emphasise the sharing of information between the person with the chronic condition, their informal supports, such as family members (where applicable), and service providers. They place emphasis on linkage and transparent communication of consistent and timely information. The various models differ in how that communication is organised, who leads the communication and how it is shared. Several of the following models are not mutually exclusive; they are likely to form necessary parts of a comprehensive system response to the chronic care needs of cancer patients regardless of where they sit in the cancer survivor journey. The Chronic Care Model [2, 3] provides an overarching framework for the management of chronic diseases and conditions within systems of care, internationally.

8.2.1 The Chronic Care Model

The Chronic Care Model, developed by the McColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation in the United States [2, 3], is an internationally recognised, evidence-based guide to the comprehensive, integrated re-organisation of care delivery needed to support chronic condition self-management. It has been expanded to include a greater focus on community resources, population health and health promotion; all issues of relevance to the service providers and systems that support people with chronic conditions who develop cancer and to cancer survivors at risk of developing comorbid chronic conditions (see Fig. 8.2). It acknowledges three important domains of influence which interact and influence each other, and which influence the quality of chronic condition management and self-management support:

-

1.

The Macro level of healthcare aims to coordinate and maintain the overall values, principles and strategies for the development of the national healthcare system. It is also the role of this level to allocate funding and resources to the appropriate sectors, to set national standards for care provision and professional practice, strengthen community action, and establish broad population health and public health frameworks.

-

2.

The Meso level of healthcare involves the necessary service delivery structures that connect policy and principles at the macro level to the actions of individual providers at the micro level. It includes the following:

-

Self-management support training and education to health professionals

-

Delivery system design to enhance service team and inter-agency communications

-

Decision support tools established to monitor and guide practice (including evidence-based guidelines)

-

Clinical information systems to enhance the recording, storage, retrieval and communication of patient data.

-

-

3.

The Micro level of healthcare involves the interactions between the health professional and the patient. The World Health Organisation (WHO) asserts that the two most common issues that occur at the micro-level are the failure of healthcare providers to adequately empower patients and a lack of emphasis on quality interactions between the patient and healthcare providers [17].

Research has shown that many processes within the Chronic Care Model are inadequate for cancer patients. A Norwegian survey, for example, with cancer patients and health professionals found that few services or training programmes had been offered to these patients after their treatment was completed. Patient participants also reported poor communication to them by service providers and their follow-up care, and also between service providers. This left cancer patients confused about which service they should contact for follow-up. Many patients reported wanting, “a more systematic post-treatment programme, as well as clear guidelines delineating the specific areas of responsibility assigned to hospitals and the local public health services” (p. 56) [22].

We describe below, programs and models of care that have been shown to improve outcomes in chronic condition management and are applicable to cancer management.

8.2.1.1 Self-help Group Programs

Patients receiving active treatment for their cancer and cancer survivors have valid forms of knowledge and expertise that are inherent in their experience as cancer patients. This expertise can inform the delivery of care and priorities for research [23, 24]. Finding cures and effective treatments for cancer, while essential, are only one aspect of the evolving picture of cancer survivorship and have given rise to a broad range of peer support networks specific to cancer survivors and cancer patients in the active stages of cancer treatment. These are both formal and informal and have reciprocity of support by others with lived experience at their core [25], similar to support groups for people with lived experience of chronic health conditions, more broadly. Arthritis, Parkinson’s disease and mental health support networks are notable examples. Peer support is well known to contribute to reduced feelings of isolation and greater feelings of empowerment through exchange of information and emotional support between peers [26–28]. The evidence for the value of patient empowerment [29] and peer support between patients with chronic health conditions is now well established [28, 30], though the evidence for psychosocial benefit for cancer patients is mixed and requires further research [31, 32].

As the cancer survivor population grows, the general community’s literacy regarding cancer survivorship needs to also grow and shift from attitudes largely driven by fear and despondency about cancer diagnoses and future survival [14], to one in which they embrace support and inclusion of cancer survivors in the community. This required shift in attitude also applies to cancer survivors given that research has shown that those who self-identify as survivors have better psychological well-being, sense of control and hope than those who relinquish responsibility for their health to health care providers [33]. This shift in perception within the community might also help to address the exclusion, isolation and stigma that some cancer patients and cancer survivors experience in the community [34, 35]. Many countries have responded to this shifting need by establishing a range of cancer advocacy, research and community information services. In Australia, Cancer Foundations exist in each jurisdiction, as do a comprehensive network of cancer support groups such as Cancer Voices Australia, CanTeen, and Foundations for specific types of cancers [36]. In the UK, Macmillan Cancer Support is an example of an organisation undertaken a range of these roles.

The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Course, developed by Kate Lorig and colleagues at Stanford University in the United State, is a prominent example of a peer-led group based program for people with chronic conditions [37, 38]. In the UK, it is known as the Expert Patient Program [39]. This group-based program has been used with cancer survivors in a range of contexts with positive outcomes [26, 40, 41] and have included web-based program delivery [42]. In the UK, Risendal et al. [43] delivered 27 workshops to 22 Cancer Thriving and Surviving (CTS) leaders and 244 cancer survivors to test their feasibility and acceptability for this population. They found 95% satisfaction with this approach and concluded that it represents, “a powerful tool toward improving health-related outcomes in this at-risk population” (p. 771) [see also 44]. Salvatore et al. [41] undertook a comparative study with 116 cancer survivors and 1054 non-cancer patients with other chronic conditions investigating the applicability of this program with cancer survivors and program outcomes. They found general health, depression, sleep, communication with health professionals, medication compliance and physical activity improved significantly, and were sustained at 12 months.

8.2.1.2 Cancer Patients and Cancer Survivors as Navigators of Existing Healthcare Systems

Central to chronic condition management is the active role of the person with the health conditions in the communication loop, given that they or their informal supports are the primary navigator across services in order to get their healthcare needs met. However, in order to do this, cancer patients need access to their health information. Hence, Cancer Council Australia [45] recommend that every cancer survivor request a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan from their specialist once they complete their cancer treatment. For cancer patients with existing chronic health conditions, this would also include the need for care summaries and routine communication about progress between oncology specialists and primary care providers with continuing responsibility for the coordination of care for the person’s other health conditions and non-cancer related acute health needs. Currently, this system navigation and communication of information between providers is done, largely, by the cancer patient; though many cancer patients may not have adequate capacity, access to their own health information or sufficient health literacy or confidence to perform these roles. The Cancer Council Australia, for example, provides a range of resources to assist cancer patients in this role (see Box 1).

Box 1: Suggested Questions for Cancer Survivors to Ask to their Specialists (Source: Cancer Council Australia [45])

-

1.

What treatments and drugs have I been given?

-

2.

How often should I have a routine visit?

-

3.

Which doctor(s) should I see for my follow-up cancer care?

-

4.

What are the chances that my cancer will come back or that I will get another type of cancer?

-

5.

What follow-up tests, if any, should I have?

-

6.

How often will I need these tests?

-

7.

What symptoms should I watch for?

-

8.

If I develop any of these symptoms, whom should I call?

-

9.

What are the common long-term and late effects of the treatment I received?

-

10.

What should I do to maintain my health and wellbeing?

-

11.

Will I have trouble getting health insurance or keeping a job because of my cancer?

-

12.

Are there support groups I can turn to?

However, this approach assumes that each patient has the capacity to be the navigator of their own care needs. It takes little account of social determinants such as access to and availability of other community resources and services, language and cultural barriers, potential levels of comorbid disability, and other factors.

8.2.1.3 Referral and Coordination of Care Between Service Providers

Research has highlighted that many cancer patients have felt abandoned by the health care system once their specialised cancer treatment is completed [19, 20]. This represents a failure in care coordination across health and support service boundaries, given that research has also confirmed that the transition period immediately following the conclusion of active cancer treatment is likely to be one of a number of highly distressing points for cancer patients, and that those patients who report higher levels of distress at such times tend to also have longer-term problems with adjustment to life after cancer [19]. Reasons for this transition stress in cancer patients relate to the loss of a safety net that was previously present through intense contact with cancer treatment providers and potentially also other cancer patients [11, 46].

In an effort to address some of these healthcare system-based communication and coordination concerns, some governments have attempted to introduce more system integration measures. Across England, for example, Cancer Networks funded centrally and through local bodies were established in 2000. The various National Health Service (NHS) organisations within each of the networks, prior to funding cuts in 2012 that reduced their number from 28 to 12 Networks, aim to work together to deliver high quality, integrated cancer services for their local populations. They bring local area clinicians, patients and managers together, “to deliver the national cancer strategy, to improve performance of cancer services and to facilitate communication and engagement around cancer issues” (p. 5) [47]. Similar networks have been established elsewhere for healthcare delivery more broadly [48]. Most recently, across Australia has been the establishment of Primary Health Networks (PHNs). These are tasked with increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of health services for patients and supporting services to improve the coordination of care for patients within and across health service sectors [49].

Specific to cancer survivorship care, six pilot projects were undertaken in Victoria, Australia to test various models of coordination of care [50]. These included shared care between cancer care services and GPs or discharge for GP follow-up and engagement within primary care. Researchers piloting these approaches reported high levels of acceptability and satisfaction with shared care/discharge to GP follow-up; however, a range of barriers were also reported which included time constraints and GP engagement. Nurse-led clinics were also piloted and included screening, information provision, linkage with other services and transition to GP follow-up; though, no comparison with other models of care was undertaken.

8.2.1.4 Cancer Survivor Care Plans

Various approaches to provision of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans (SCPs) have been explored among cancer survivors [51, 52]. Notably, the focus of these SCPs has been on cancer specific management, rather than patient-led identification of self-management needs, strengths and barriers that may influence their lifestyle behaviour and engagement in care plans [53]. We know that cancer patients’ involvement in cancer care can benefit their capacity to live well with cancer, refocusing their lives, “in a positive, purposeful and productive way” [54]. However, initial uncertainty and vulnerability about the longer-term future might hamper the process of cancer patients’ active involvement in care planning for the longer-term, at least in the early transition phase for some patients [46].

In a pilot project report by Howell et al. [50], SCPs were positively received by cancer survivors and also perceived as a valuable communication tool by service providers across secondary and primary care. They also found that GPs were more likely to discuss SCPs with cancer survivors where shared care arrangements were in place with secondary care cancer care providers. GPs were also more likely to find SCPs helpful and relevant when information was presented in chronic condition management terms; though, time constraints were reported as a barrier to full integration of this approach.

The Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre [55] undertook an evaluation of SCPs with a large sample of cancer survivors, nurse coordinators and general practitioners (GPs) and concluded that most participants found their SCPs useful. However, over half of cancer survivor participants had not discussed their SCP with their GP. All nurse coordinators felt that SCPs were useful because they improved their communications with the cancer survivor’s GP. Most GPs reported receiving a copy of the SCP, most had read it, but few had discussed it with their patient. Few SCPs led to the development of chronic condition self-management care plans. Limited time and resources, competing demands, and inadequate leadership and commitment within the organisation were reported as reasons for limited GP involvement. A range of recommendations were proposed:

-

Improved organisational commitment, leaders and multidisciplinary engagement

-

Education across all sectors to improve understanding, awareness and practice tools

-

Better IT systems to improve communication

-

Dedicated resources to enable the implementation of SCPs across clinical services

-

More evaluation to provide more rigorous evidence.

8.2.1.5 Nurse-led Clinics

The growth in the scope of role for primary health care nurses offers one (PHCNs) way forward to addressing the barriers to effective chronic condition management [56], more broadly, with primary care, and there has been increasing focus on their role [49]. Within primary care settings where cancer patients will usually begin their contact with the health system for any chronic conditions, and for the screening of risks for cancer [7], the PHCN is an important frontline health worker who could play an important role in the development and delivery of a coordinated holistic model of cancer survivorship care and chronic condition prevention, management and self-management support [57]. McCorkle et al.’s [7] review of self-management approaches for cancer survivorship care stress the complexity of the care continuum for cancer survivors and the need for a champion to provide links between primary care and oncology providers (with relevance also to all cancer patients). This would occur within what they refer to as the ‘practice home’ in order to make chronic condition care planning possible for this group. In Australia, there are over 10,000 PHCNs within general practice, with more than 60 % of clinics employing a PHCN in Australia today. Their growth has been supported by a range of funding initiative and structural changes to the way general practices are funded, to support them to address the needs of patients with chronic conditions [58, 59].

8.2.1.6 Collaborative Care: Chronic Condition Self-Management Support (The Flinders Program)

Collaborative care has emerged as a significant model in the management of chronic disease. It has both economic drivers but also a social justice focus underpinned by empowerment [60, 61]. This is demonstrated by Lawn et al. [18] who state:

Self-management support provided through a partnership between the patient and support providers reverses the focus on telling patients what they ‘should do’ to one where the patient is supported in addressing their own agenda. It is integral in delivering more person-centred care which promotes greater patient autonomy and control, and patient/health professional collaboration, and re-establishing patients’ personal ownership of health… This may be especially important for people who have experienced cancer and survived, particularly because many cancer patients report heightened feelings of fear and powerlessness in the face of a cancer diagnosis and the threat of its recurrence (p. 3358) [see also 62, 63].

Reflective of this empowerment framework, the nationally agreed principles underpinning effective chronic condition management and self-management support established for the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing [64] provide a useful framework in which to position the role of chronic condition management and self-management for cancer survivors.

Box 2: Capabilities and Underlying Principles for Effective Self-Management (KICMRILS)

-

Know your condition

-

Be actively Involved with the health practitioners to make decisions and navigate the system

-

Follow the Care plan that is agreed upon with the GP and other health practitioners

-

Monitor symptoms associated with the condition(s) and Respond to, manage and cope with the symptoms

-

Manage the physical, emotional and social Impact of the condition(s) on your life

-

Live a healthy Lifestyle

-

Readily access Support services.

Box 3: Underlying Principles and Processes for Effective Self-Management Support

-

Assessment of self-management (learn what the patient knows, their actions, strengths and barriers)

-

Collaborative problem definition (between patient and their health practitioners)

-

Targeting, goal setting and planning (target issues of greatest importance to patient, set realistic goals and develop personalised care plan)

-

Self-management training and support services (instruction on disease management, behavioural support, and address physical and emotional demands of chronic condition)

-

Active and sustained follow-up (reliable follow-up leads to better outcomes).

One example of how chronic condition self-management support has been operationalized into practice is the Flinders Program of Chronic Condition Care Planning [65] (see Fig. 8.3). This program incorporates the above principles of self-management by the patient and the self-management support by health care providers, families and other support providers in the community. It is an evidence-based, structured interview process, using cognitive behavioral and motivational processes that allow for assessment of self-management behaviors, enablers and barriers to change, and collaborative identification of problems and goals, leading to the development of an individualized person-centered self-management care plan [65, 66]. It includes the following steps:

-

1.

The Partners in Health Scale (PIH): A patient Likert-rated validated questionnaire informed by the WHO and Australian National Chronic Disease Strategy principles of self-management [67, 68]. It enables measurement of perceived change over time where 0 = less favorable and 8 = more favorable self-management capacity. Self-management rated capacities include: knowledge of condition and treatments; quality of relationships with healthcare providers; actions taken to monitor and respond to signs and symptoms; access to services and supports; physical, social and emotional impacts, and lifestyle factors.

-

2.

The Cue and Response Interview (C&R): An adjunct to the PIH using open-ended questions or cues to explore the patient’s responses to the PIH in more depth, with the patient and worker comparing their Likert-ratings to identify agreed good self-management, agreed issues that need to be addressed, and any discrepancies in views that can then be discussed as part of formulation of a self-management care plan. It enables the strengths and barriers to self-management to be explored, and checks assumptions that either the worker or patient may have, as part of a motivational process.

-

3.

The Problems and Goals (P&G) Assessment: Defines a problem statement from the patient’s perspective (the problem, its impact and how it makes them feel) and identifies specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely (SMART) goals that they can work towards. It is Likert-rated, allowing measurement of progress over time where 0 = not a problem and 8 = a significant problem; and goal statements: 0 = no progress towards achievement and 8 = achieved.

-

4.

Self-Management Care Plan: Includes self-management issues, aims, steps to achieve them, who is responsible and date for review.

The Flinders Program (adapted for prevention) has been trialled with a small sample of 25 cancer patients being treated with curative intent to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of these care planning tools with this population [18]. Of note, both cancer patients in the active phase of treatment and later in their cancer treatment trajectory found this approach acceptable as a means of helping them to develop and achieve their nutrition and physical activity goals. Building self-management capacity during the active phase of cancer treatment, rather than waiting for treatment to be completed, has appeared to provide health and psychosocial benefits.

8.3 Future Direction for Research and Practice

McCorkle et al. [7] in their review of self-management for cancer survivors stressed that a major limitation to this approach has been the lack of a common language that is understandable to health professionals across the disciplines and to cancer survivors and their families. They also argue that there needs to be a common set of actions to teach cancer patients and families how to self-manage, and greater guidance on how to support their participation according to their preferences and abilities, and their specific experiences as cancer patients.

More broadly, more research is needed to understand the range of enablers and barriers to implementation of chronic care models into practice for this population. Davy et al.’s [69] recent systematic review of factors influencing implementation of chronic condition management models identified 38 papers addressing this issue. They identified the following themes, each suggesting further areas for research and practice development that might also be relevant to cancer patients and cancer survivors with comorbid chronic conditions or risk factors for their development:

-

Acceptability of the interventions for healthcare providers and patients

-

Preparation of healthcare providers for a CCM approach, including communication needs, necessary incentives for change, skills development and the potential role of leaders and champions

-

Supporting patients for a CCM approach, given their diverse needs and preferences in engaging with care

-

The resources needed for implementation and sustainability of a CCM approach, including information and communication requirements, funding, collaborations, monitoring and evaluation.

Similar themes were identified by Mitchell et al. [70] in their systematic review of integrated models of care at the primary-secondary interface. Effective models contained the following elements: interdisciplinary teamwork, communication information exchange, shared care guidelines or pathways, training and education, access and acceptability for patients, and a viable funding model.

Other considerations that represent clear gaps in current knowledge and practice, for cancer patients, cancer survivors and patients with chronic conditions more broadly, are also worthy of mention:

-

What is the role of palliative care in the chronic disease continuum for cancer patients and patients with chronic conditions more broadly?

-

What role should chronic condition management models play for people with chronic conditions who are then diagnosed with cancer or going through acute cancer treatment, or dying of cancer?

-

How could Advance Care Directives be incorporated into chronic condition management models involving cancer patients and cancer survivors and more broadly [71]?

-

What is the role of information technology systems solutions to address fragmented care and enhance coordination and communication across the cancer care/chronic care continuum?

-

What would sustainable models of shared care that include the role of PHCNs look like?

Overall, further translational research is also needed to determine the acceptability and feasibility of these approaches with cancer patients during active treatment for their cancer and for cancer survivors, and to better understand enablers and barriers for clinicians embedding these approaches into routine chronic condition care and cancer survivorship care.

References

Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C (2016) The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin Early Online. doi:10.3322/caac.21342

Wagner E, Austin B, von Korff M (1996) Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 74:511–514

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A (2001) Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 20(6):64–78

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parking D (2010) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2012) Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: period estimates from 1982–2010. AIHW, Canberra. http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737422721. Cited 5 Feb 2016

de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, Forsythe L, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Rowland JH (2013) Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomar 22(4):561–570

McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, Wagner EH (2011) Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin 61(1):50–62

Institute of Medicine (2013) Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. The National Academics Press, Washington, DC

Boger E, Ellis J, Latter S, Foster C, Kennedy A, Jones F, Feneerty V, Kellar I, Demain S (2015) Self-management and self-management support outcomes: a systematic review and mixed research synthesis of stakeholder views. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0120990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130990

Taylor S, Pinnock H, Epiphanou E, Pearce G, Parke H, Schwappach A et al (2014) A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS—Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Health Serv Delivery Res 2(53). http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/volume-2/issue-53#scientific-summary. Cited 11 Mar 2016

Jefford M, Lofti-Jam K, Baravelli C, Grogan S, Rogers M, Krishnasamy M et al (2011) Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 34(3):E1–E10

Karahalios A, Baravelli C, Carey M, Schofield P, Pollard A, Aranda S et al (2007) An audiovisual information resource to assist in the transition from completion of potentially curative treatment for cancer through to survivorship: a systematic development process. J Cancer Survivorship 1:226–236

Earle CC, Ganz PA (2012) Cancer survivorship care: don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. J Clin Oncol 30:3764–3768

Macmillan Cancer Support (2013) Routes from diagnosis. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/AboutUs/Research/Researchandevaluationreports/Routes-from-diagnosis-report.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Del Guidice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, Piliotis E, Verma S (2009) Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 27:3338–3345

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2005) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies Press, Washington DC

World Health Organization (WHO) (2002) Innovative care for chronic conditions. WHO, Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMC_CCH_02.01.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Lawn S, Zrim S, Leggett S, Miller M, Woodman R, Jones L, Kichenadasse G, Sukumaran S, Karapetis C, Koczwara B (2015) Is self-management feasible and acceptable for addressing nutrition and physical activity needs of cancer survivors? Health Expect 18(6):3358–3373

Allen J, Savadatti S, Levy A (2009) The transition from breast cancer ‘patient’ to ‘survivor’. Psycho-Oncology 18:71–78

Jefford M, Karahalios E, Pollard A, Baravelli C, Carey M, Franklin J et al (2008) Survivorship issues following treatment completion—Results from focus groups with Australian cancer survivors and health professionals. J Cancer Survivorship 2:20–32

Lance Armstrong Foundation (2010) “I learned to live with it” is not good enough: challenges reported by post-treatment cancer survivors in the Livestrong surveys. A Livestrong Report. Lance Armstrong Foundation, Austin, Texas. https://assets-livestrong-org.s3.amazonaws.com/media/site_proxy/data/a54320d560396f8742fa490257c442829f5be4b2.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Saegrov S, Lorensen M (2006) Cancer patients’ opinions concerning post-treatment follow up. Eur J Cancer Care 15:56–64

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, Suleman R (2014) A systematic review of impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient 7:387–395

Ward PR, Thompson J, Barber R, Armitabe CJ, Boote JD, Cooper CL, Jones GL (2010) Critical perspectives on ‘consumer involvement’ in health research: epistemological dissonance and the know-do gap. J Sociol 46:63–82

Solomon P (2004) Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiat Rehab J 27:392–401

Beckmann K, Strassnick K, Abell L, Hermann J, Oakley B (2007) Is a chronic disease self- management program beneficial to people affected by cancer? Aust J Prim Health 13:36–44

Dennis C (2003) Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 40:321–332

Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, Bell M, Nyhof-Young J, Sale JEM, Britton N (2013) The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns 92(1):3–12

Anderson R, Funnell M (2010) Patient empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Pat Educ Couns 79:277–282

Funnell MM (2010) Peer-based behavioural strategies to improve chronic disease self-management and clinical outcomes: evidence, logistics, evaluation considerations and needs for future research. Fam Pract Suppl 1:i17–i22

Hoeya LM, Ieropolia SC, Whitea VM, Jefford M (2008) Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns 70(3):315–337

Carlsson C, Nilbert M, Nilsson K (2005) Supporter or obstructer; experiences from contact person activities among Swedish women with breast cancer. BMC Health Serv Res 5:9–17

Park C, Zlateva I, Blank T (2009) Self-identity after cancer: “survivor”, “victim”, “patient”, and “person with cancer”. J Gen Internal Med 2(2):430–435

Carlisle D (2011) Vocational rehabilitation: A job that is worth doing well. Health Serv J 121(6252):10–11

Lebel S, Devins GM (2008) Stigma in cancer patients whose behavior may have contributed to their disease. Future Oncol 4(5):717–733

Australian Government/Cancer Australia (2015) Cancer support organisations. Australian Government/Cancer Australia, Canberra. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-support-organisations. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Bandura A, González VM, Laurent DD, Holman HR (2001) Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care 39(11):1217–1223

Stanford Patient Education Research Centre (2015) Chronic disease self-management program. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Wilson PM, Kendall S, Brooks F (2007) The Expert Patients Programme: a paradox of patient empowerment and medical dominance. Health Soc Care Comm 15(5):426–438

Kravitz RL, Tancredi DJ, Grennan T, Kalauokalani D, Street RL, Slee CK, Wun T, Wright Oliver J, Lorig K, Franks P (2011) Cancer health empowerment for living without pain (Ca-Help): effects of a tailored education and coaching intervention on pain and impairment. Pain 152(7):1572–1582

Salvatore AL, Ahn S, Jiang L, Lorig K, Ory MG (2014) National study of chronic disease self-management: six- and twelve-month findings among cancer survivors and non-cancer survivors. Fron Public Health 2:214 (eCollection)

Bantum EO, Albright CL, White KK, Berenberg JL, Layi G, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Plant K, Lorig K (2014) Surviving and thriving with cancer using a web-based health behavior change intervention: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 16(2):e54

Risendal BC, Dwyer A, Lorig K, Coombs L, Kellar-Guenther Y, Warren L, Franco A, Ory MG (2014) Adaptation of the chronic disease self-management program for cancer survivors: feasibility, acceptability, and lessons for implementation. J Cancer Educ 29(4):762–771

Risendal BC, Dwyer A, Seidel RW, Lorig K, Coombs L, Ory MG (2015) Meeting the challenge of cancer survivorship in public health: results from the evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program for cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol (ePub). doi: 10.1002/pon.3783

Cancer Council Australia (2015) Cancer in general practice—a practical guide for primary health care nurses. http://gp.cancer.org.au/video/cancer-in-general-practice-a-practical-guide-for-primary-health-care-nurses-3-of-3/. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Shaha M, Cox CL, Belcher A, Cohen MZ (2011) Transitoriness: patients’ perception of life after a diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Nurs Pract 10(4):24–27

Macmillan Cancer Support (2012) The role of cancer networks in the new NHS. Report. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/GetInvolved/Campaigns/TheroleofcancernetworksinthenewNHS.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Hutchison B, Levsque J, Strumpf E, Coyle N (2011) Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q 89(2):256–288

Department of Health (2015) Primary health networks (PHNs). Department of Health, Canberra. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/primary_health_networks. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Howell P, Kinnane N, Whitfield K (2014) Supporting cancer survivors in Victoria: summary report. Learning from the Victorian Cancer Survivorship Program pilot projects 2011–2014. Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne http://www.petermac.org/sites/default/files/Education/Supporting%20cancer%20survivors%20in%20Victoria%20-%20summary%20report.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR (2011) Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:1101–1109

Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G et al (2011) Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4755–4762

Smith TJ, Snyder C (2011) Is it time for (survivorship care) plan B? J Clin Oncol 29:4740–4742

Cotterell P, Harlow G, Morris C et al (2011) Service user involvement in cancer care: the impact on service users. Health Expect 14:159–169

Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre (2014) Evaluation of the implementation of survivorship care plans at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, Melbourne. http://www.petermac.org/sites/default/files/Education/Evaluation%20fo%20the%20implementation%20of%20survivorship%20care%20plans%20at%20Peter%20Mac_2014.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Australian Practice Nurses Association (APNA) (2016) Definition of the primary health care nurse. http://www.apna.asn.au/scripts/cgiip.exe/WService=APNA/ccms.r?PageId=11012. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Anderson DR, St Halaire D, Flinter M (2012) Primary care nursing role and care coordination: an observational study of nursing work in a community health center. Online J Issues Nurs 17(2) (Manuscript 3)

Haji Ali Afzali H, Karnon J, Beilby J, Gray J, Holton C, Banham D (2014) Practice nurse involvement in general practice clinical care: policy and funding issues need resolution. Aust Health Rev 38(3):301–305

Kelehera H, Parker R (2013) Health promotion by primary care nurses in Australian general practice. Collegian 20(4):215–221

Thille PH, Russell GM (2010) Giving patients responsibility or fostering mutual response-ability: family physicians’ constructions of effective chronic illness management. Qual Health Res 20:1343–1352

Pulvirenti M, McMillan J, Lawn S (2012) Empowerment, patient centred care and self-management. Health Expect (Early online:1–8)

Aujoulat I, Luminet O, Deccache A (2007) The perspective of patients on their experience of powerlessness. Qual Health Res 17:772–785

Foster C, Fenlon D (2011) Recovery and self-management support following primary cancer treatment. Brit J Cancer 105:S21–S28

Lawn S, Battersby MW (2009) Capabilities for supporting prevention and chronic condition self-management: a resource for educators of primary health care professionals. Flinders University/Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Adelaide

Flinders Human Behaviour, Health Research Unit (FHBHRU) (2015) ‘The Flinders Program™’. FHBHRU, Adelaide. http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Battersby MW, Harvey P, Mills PD et al (2007) SA HealthPlus: a controlled trial of a state-wide application of a generic model of chronic illness care. Milbank Q 85:37–67

Battersby M, Ask A, Reece M, Markwick M, Collins J (2003) The partners in health scale: the development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management. Aust J Prim Health 9:41–52

Petkov J, Harvey PW, Battersby MW (2010) The internal consistency and construct validity of the Partners in Health scale: validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Qual Life Res 19(7):1079–1085

Davy C, Bleasel J, Liu H, Tchan M, Ponniah S, Brown A (2015) Factors influencing the implementation of chronic care models: a systematic literature review. BMC Fam Pract 16:102–113

Mitchell GK, Burridge L, Zhang J, Donald M, Scott IA, Dart J, Jackson CL (2015) Systematic review of integrated models of health care delivered at the primary-secondary interface: how effective is it and what determines effectiveness? Aust J Prim Health 21:391–408

Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J (2014) A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advanced care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J Adolesc Health 54:710–717

Further Reading

Australian Government/Cancer Australia (2016) Promoting self-management. http://cancersurvivorship.net.au/self-management. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Cancer Council Australia (2016) Cancer in General Practice: a guide for primary health care nurses. http://gp.cancer.org.au/video/cancer-in-general-practice-a-practical-guide-for-primary-health-care-nurses-3-of-3/. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Davies NJ, Batehup L (2010) Self-management support for cancer survivors: guidance for developing interventions—An update of the evidence. Macmillan Cancer Support, London. http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Guidance-for-Developing-Cancer-Specific-Self-Management-Programmes.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Heisler M (2006) Building peer support models to manage chronic disease: seven models for success. http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20B/PDF%20BuildingPeerSupportPrograms.pdf. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Macmillan Cancer Support (2011) Supported self-management. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/Aboutus/Healthandsocialcareprofessionals/Newsandupdates/MacVoice/Supportedself-management.aspx. Cited 5 Feb 2016

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2016) Managing Cancer as a Chronic Condition. http://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_after_cancer/managing.aspx. Cited 5 Feb 2016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lawn, S., Battersby, M. (2016). Chronic Condition Management Models for Cancer Care and Survivorship. In: Koczwara, B. (eds) Cancer and Chronic Conditions. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1844-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1844-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-1843-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-1844-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)