Abstract

The relationship between a supervisor and a research student can ‘make or break’ the student’s success and pursuit of original contribution to knowledge development. Although the nature of the supervision relationship has evolved over time, studies about supervisor-student relationships have not fully examined the influence of the key factors associated with relational exchange. In this paper, we develop a conceptual model depicting the antecedents of supervisory relationship satisfaction. In developing the current paper, we draw from the extensive relationship marketing literature and are inspired by the relational model of focal sponsorship exchange by Farrelly and Quester (2005). Our arguments are also supported by a comprehensive reflection of the research supervision relationship between Professor Pascale Quester and the first author of this paper, as well as that between the second author and his supervisor. We argue that supervisor’s trust and commitment in the relationship are two key drivers of student’s and supervisor’s satisfaction with the relationship. We also propose congruence moderates these key relationships such that the relationship is stronger with higher congruence.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Sit back, relax, and enjoy the process! (Pascale Quester)

Those were the wise words that Professor Pascale Quester frequently said to the first author of this paper when he was frustrated by various challenges along his PhD research candidature. Professor Quester, through her research prominence, sustained discipline leadership, and significant supervision experience, has inspired generations of PhD students who have gone on to accomplish major success both within and outside of academia in Australia and overseas. Professor Quester has had a profound impact on her students’ research and career accomplishments through the art of supervision and through her command of what constitutes a mutually satisfying supervisor-student relationship.

Indeed, the supervision relationship is one of the key factors in facilitating the research students’ learning outcomes (Heath 2002). A satisfying relationship is also pivotal to the timely completion of the research degree (Hemer 2012) and remains a major part of the higher degree by research experience. Evidence-based recommendations for research supervisors emphasise the importance of regular meetings during candidature, as well as the need for effective feedback to be provided to students (Heath 2002). While these are important considerations for supervisors, less attention has been provided to the nature of the supervision relationship and how to maximise the benefits of regular meetings and effective feedback.

Traditional models of research supervision can be likened to a master-apprentice relationship, where supervisors are more experienced and hierarchically superior to less experienced supervisees. Recent research suggests that traditional master-apprentice models of supervision may be problematic because (a) they position supervisors as the single resource available to students, (b) students need more well-rounded skill sets post-graduation than supervisors alone can provide, and (c) hierarchies of power might damage supervision relationships and put the candidature at risk (Harrison and Grant 2015). Thus models of supervision that move away from master-apprentice styles of relationship might provide more useful frameworks for supervision practice.

Contemporary models of supervisory relationships conceptualise supervision as more of a collaborative activity undertaken without strict hierarchies of power (Hemer 2012). Indeed, when supervision is not too didactic, students may be more likely to engage in candid conversations about their needs and future goals (Duxbury 2012). An important part of the supervisory relationship is the role of supervisors in instilling confidence in research candidates (Duxbury 2012). Sidhu et al. (2015) describe ideal research supervision as facilitative across relevant domains, with the goal to support the participation of the candidate in academic practice. Through more equal relationships, research students should be better endowed to engage in driving their own research processes, and to develop a better sense of trust in supervisors.

In order to understand the mechanics of the supervision relationship, it is useful to turn to Hockey’s (1994) discussion, which elaborates on two dimensions of the relationship: an intellectual dimension, and a pastoral dimension. In discussing how to balance these dimensions of supervision, Hemer (2012) suggests that supervisors consider having some research meetings over coffee or in more informal locations. Although some supervisors report a sense of anxiety over how to maintain boundaries in establishing social relationships with students, some positive aspects of engaging with research students in neutral locations include the levelling of hierarchies, greater willingness of students to engage in more open communication with supervisors, and a strengthening of relationships. Indeed, in order to develop more collaborative partnerships between supervisors and supervisees, researchers have emphasised the importance of supervisors having a better understanding of students’ needs (de Kleijn et al. 2015). As yet, there has been little research exploring how this might be done, and how to integrate adaptability into the supervisory relationship. In this conceptual paper, we propose a framework through which supervisors might consider how to develop particular aspects of the supervisory relationship.

This brief conceptual piece extends the relationships in sponsorship effectiveness to the research supervision relationships. To this end, our framework draws inspiration from the model of satisfaction in sponsor-sponsee relationships developed and empirically tested by Farrelly and Quester (2005). Their findings focus on sponsors’ commitment and trust in the sponsorship relationship as antecedents of both noneconomic and economic relationship satisfaction in the sports industry. They also suggest that sponsors’ non-economic satisfaction acts as an antecedent to their economic satisfaction in the relationship. In the current study, we argue that the elements of trust and commitment are important in supervisory relationships in similar ways to the propositions of Farrelly and Quester (2005) in regards to sponsorship relationships. Instead of focusing on economic and noneconomic satisfaction, our model of supervision relationships focuses on intellectual and pastoral dimensions of supervision proposed by Hockey (1994). Thus our model of supervision satisfaction proposes that supervisors’ trust and commitment in a supervision relationship are antecedents of satisfaction with both the intellectual and the pastoral dimension of the relationship.

Take a Chance on Me (Andersson and Ulvaeus 1978)

Trust is one of the most common and historical variables in the literature (Seppänen et al. 2007) and is a critical construct in relational exchange (Dwyer and Oh 1987). Trust reflects the belief of an exchange party that its requirements will be fulfilled through future actions undertaken by the other party (Anderson and Weitz 1989; Barney and Hansen 1994). As a result, a trusting relationship is one in which the involved parties do not engage in opportunistic behaviour, thereby decreasing uncertainty in the relationships (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In the sponsorship model developed by Farrelly and Quester (2005), trust from the sponsors has a direct effect on their satisfaction with the relationship. Farrelly and Quester (2005, p. 216) highlight that “risk-laden activities, such as sponsorship leveraging, are more likely to be attractive if there is the knowledge that the sport entity will not take advantage of the vulnerability associated with the investment”.

Similarly, trust, warmth and honest collaboration are the key relationship characteristics driving successful supervision of students (Blumberg 1977). Indeed, the supervisor’s trust is critical to the student’s focus and progress. From our own experience in working with our PhD supervisors, there are multiple ways for a supervisor’s trust to be demonstrated. The supervisor can show their appreciation of the students’ work ethics and self-initiatives. The supervisor can also instil the belief that the student will be honourable with the delivery of the research milestones or outputs, and that the student can work productively and independently with limited supervision. Further, the supervisor can actively encourage the student to voice his/her feedback and opinions.

From a student’s point of view, the activities by the supervisor affirm the supervisor’s faith and a sense of respect toward his or her own capabilities. Without trust on the part of the supervisor, the students will either give up or refrain themselves from going beyond the acceptable boundaries defined by the supervisors (Pearson and Brew 2002). In other words, the supervisor’s trust will lead to a satisfying working relationship. More specifically, such satisfaction results from the fact that the students will make the most of their learning and intellectual development opportunity offered by the supervisor, and the supervisor is confident that their ‘investment’ in the supervisory relationship is worthwhile. As such, we propose that:

-

P1: Supervisors’ trust in the relationship is positively related to both students’ and supervisors’ satisfaction with the relationship.

I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (Andersson et al. 1975)

Commitment refers to “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” (Moorman et al. 1992, p. 316), and is an essential element for a successful relationship (Gundlach et al. 1995) that leads to achieving valuable outcomes (Morgan and Hunt 1994). For instance, commitment can significantly influence customer loyalty and expectations of relationship continuity (Palmatier et al. 2006).

In their study of the focal sponsor-sponsee relationship, Farrelly and Quester (2005, p. 212) define commitment was “a willingness of the parties in the sponsorship relationship to make short term investments in an effort to realise long-term benefits from the relationship”. They argue that the sponsor can signal their long-term commitment to the relationship in the form of additional investments and leveraging activities (e.g. allocation of additional resources over and above the initial agreement). In order to promote the relationship and realise its long term and strategic benefits, Farrelly and Quester (2005) further suggest the sponsor (i) develop a clear set of sponsorship objectives, (ii) integrate sponsorship agreements into their marketing or corporate plan, and (ii) foster a confident future outlook for the relationship. In our experience, these elements also lay a very robust foundation for the development of commitment in the context of supervisor-student relationship.

A reflection of our working relationship during and beyond the doctoral research candidature with our own supervisors indicates that they indeed undertook a wide range of activities to demonstrate their full commitment to us and to the relationship. From the beginning of the relationship, and even before students commence their candidatures, a supervisor can show a great deal of enthusiasm towards the student’s potential research topic. Extending Farrelly and Quester’s (2005) focus on the sole perspective of the sponsor, we argue that, in the research supervision context, the supervisor should enable the student to co-create a meaningful learning experience by working together on an agreed set of clear and achievable goals. Through an effective two-way interaction, the supervisor remains a strong source of aspiration and guidance for the student when he/she is confronted by various research and career uncertainties.

Additionally, the supervisor’s commitment to the relationship is strengthened by their willingness to invest additional time and resources, such has having an open door policy for the student, maintaining a 24-h turnaround time for feedback on research papers or thesis chapters, and even providing extra funding for the student’s research endeavour and conference attendance. Such commitment is further extended to the supervisor’s efforts in introducing and integrating the student into their own network of professional connections and relationships, which is instrumental to the student’s future career success. Further, we support Farrelly and Quester’s (2005) argument that the supervisor’s commitment to the supervisory relationship creates a rewarding relational atmosphere. Such atmosphere allows both supervisor and student to achieve their individual and mutual goals without opportunistic behaviours. It also fulfils the supervisor’s desire to nurture an academic talent and foster a long-term collegial and professional relationship. As such, we propose that:

-

P2: Supervisors’ commitment to the relationship is positively related to both students’ and supervisors’ satisfaction with the relationship.

I Have a Dream (Andersson and Ulvaeus 1979)

Congruence, in the context of sponsorship, has been conceptualised as the relevancy and expectancy of the relationship between sponsors and those sponsored (Fleck and Quester 2007). It has been claimed that congruence between perceptions of sponsors and sponsees has been one of the most commonly researched concepts within the literature about sponsorship (Spais and Johnston 2014). While the dominant trend in the field appears to support the argument that congruence between sponsors and sponsees would have a positive impact on the sponsor’s brand, Fleck and Quester (2007) propose that the relationship may be somewhat more complex. They argue that some incongruence between the sponsor and the sponsored partner may be more cognitively stimulating, and therefore more successful than complete congruence (and certainly more than complete incongruence).

Critical readings of congruence have noted that perceptions of congruence might differ across contexts in at least two ways. First, perceptions of congruence might differ between individuals. For instance, Spais and Johnston (2014) suggest consumer perspectives about sponsor-sponsee congruence might be quite different from the perspectives of those in management positions. It is, thus, beneficial to examine this phenomenon across contexts, rather than assuming the similarity between different individuals’ perspectives of congruence. Second, there might be multiple aspects in which two entities are congruent. For instance, Macdougall et al. (2014) expand on two different kinds of sponsor-sponsee congruence: mission congruence (where the two entities are congruent in terms of what they do) and value congruence (where the entities are congruent in terms of aspirations). It might be useful to be mindful of congruence between two entities as encompassing multidimensional aspects.

Surprisingly, congruence in research supervision relationships has received little research attention. There have, however, been some useful insights into how congruence between supervisors and supervisees is currently being theorised in studies of higher education.

One way in which congruence can be theorised in terms of the supervision relationship, is in terms of supervision styles. Deuchar (2008) focuses on congruence in supervision styles in terms of the extent to which students valued autonomy or dependency, and how hands-on or hands-off a supervisor might be. He argued that these dimensions of the supervision relationship might change throughout the course of the research project, and, therefore, that congruence in the relationship could depend on flexibility of supervisors and supervisees to renegotiate needs over time.

A second way in which congruence in supervision has been researched is in terms of the cognitive congruence between supervisors and supervisees. Armstrong et al. (2004) categorise supervisors and students into either primarily analytic or primarily intuitive cognitive styles. They find that although similarity in cognitive styles within the supervision dyad did not appear to be related to the socioemotional aspects of the relationship, it did appear that a mismatch in cognitive styles might be beneficial. Thus, consistent with Fleck and Quester’s (2007) proposal that congruence in sponsorship is unlikely to be unidimensional, congruence in supervision also appears likely to be more multidimensional and contextual.

We contend that there are other factors within the supervision dyad that have yet to be researched that might impact on the relationship between the supervisor and supervisee. For instance, congruence between students and supervisors on dimensions of epistemology, methodology, and goals are likely to influence interactions between them. It is also easy to imagine cases where supervisor’s perspectives on congruence differ from those of students, as is the case for sponsors, sponsees, and consumers. As with understandings of congruence in sponsorship, nuance of understandings of congruence in supervision is still developing.

In our experience, we chose our supervisors because we saw a shared vision and our relationship worked because of a mutual view on the collaborative nature of the relationships. This may be different from person to person—it may be a shared vision for social change, a shared way of understanding the world, or a shared way of completing projects. These shared attitudes, orientations, or processes strengthen the relationship between supervisor and student over time. We suggest that this is because greater congruence increases the strength of the relationships between trust and relationship satisfaction, and commitment and satisfaction, such that:

-

P3: Congruence moderates the relationship between (a) supervisor trust and supervisory relationship satisfaction and (b) supervisor commitment and supervisory relationship satisfaction, such that the relationship is stronger with higher congruence.

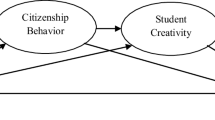

Figure 1 depicts our conceptual framework for the positive influence of supervisor’s trust, supervisor’s commitment, and congruence on student’s and supervisor’s satisfaction with the relationship. In this framework, we only took into account the level of trust and commitment exhibited by the supervisor. Future research can empirically test our propositions and extend this relational framework by including the effects of trust and commitment demonstrated by the student in their working relationship with the supervisor.

When All Is Said and Done (Andersson and Ulvaeus 1981)

Ideal dyadic relationships in a supervision context should be driven by trust, openness, mutual understanding, communication, and collaboration (Carifio and Hess 1987; Johnson 2007). Nevertheless, such relationships can be challenged by uncertainty and confusion, creative tensions and even disjunction in expectations (Malfroy 2005). Importantly, the current system for higher degree research puts a significant emphasis on timely completions and financial implications, adding an additional layer of external pressure on supervisor-student relationships.

Inspired by the focal sponsorship exchange model by Farrelly and Quester (2005), we develop a conceptual model in which supervisor’s trust, supervisor’s commitment, and relational congruence drives satisfaction in the supervisory relationship. The foundation of a satisfactory relationship can be established at the candidate selection and supervisor-student matching phase. It is then that the supervisor can judge the student’s level of enthusiasm, confidence, and commitment to the potential research topic (or other factors that might be important to individual supervisors). Students might approach individual researchers because of particular congruence they perceive between themselves and these potential supervisors, and thus it might be useful to listen to their perspectives about their specific preferences and ideas.

In the early stages of the relationship, it is essential that the supervisor and the student identify working styles and supervisory styles that they are both comfortable with. For instance, this can be partially done via a completion of the questionnaire on supervisor-doctoral student interaction (Mainhard et al. 2009). The mutual agreement on expectations and shared vision from both sides of the relationship can act as a form of psychological contract that drives the quality of and the degree of trust in the relationship. Given that trust and commitment accumulate over time, these initial steps will provide supervisors and supervisees with better understandings of how they will work together as the project progresses.

During the research candidature, the supervisor can create initiatives to shape a collegial environment (Malfroy 2005) through research retreats and encouragement of knowledge-sharing amongst research students. Open and quality communication can also offer an important venue to foster congruence (whichever form of congruence there may be between any given supervisor and supervisee). Supervision meetings over a coffee (Hemer 2012), or in other more informal settings can create a more welcoming atmosphere for a student to discuss their concerns and seek feedback from the supervisor. The authors also fondly remember dancing at conferences with their supervisors just because sometimes “you’re in the mood for a dance” (Andersson et al. 1976). These informal aspects of the relationship might increase overall supervision satisfaction.

Finally, we believe that the relational model in research supervision can, and should, continue beyond the student’s candidature. As today’s students will be tomorrow’s supervisors, sustained working relationships between the supervisor and their (former student) colleague might also benefit the progress and success of the future generation’s PhD students.

References

Anderson E, Weitz B (1989) Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Mark Sci 8(4):310–323

Andersson B, Ulvaeus B (1978) Take a chance on me [Recorded by ABBA]. On ABBA: The album. Polar Music, Stockholm

Andersson B, Ulvaeus B (1979) I have a dream [Recorded by ABBA]. On Voulez-Vous. Polar Music, Stockholm

Andersson B, Ulvaeus B (1981) When all is said and done [Recorded by ABBA]. On the visitors. Polar Music, Stockholm

Andersson B, Ulvaeus B, Anderson S (1975) I do, I do, I do, I do, I do [Recorded by ABBA]. On ABBA. Polar Music, Stockholm

Andersson B, Ulvaeus B, Anderson S (1976) Dancing queen [Recorded by ABBA]. On arrival. Polar Music, Stockholm

Armstrong SJ, Allinson CW, Hayes J (2004) The effects of cognitive style on research supervision: a study of student-supervisor dyads in management education. Acad Manag Learn Educ 3(1):41–53

Barney JB, Hansen MH (1994) Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strateg Manag J 15:175–190

Blumberg A (1977) Supervision and interpersonal intervention. J Classroom Interact 13(1):23–32

Carifio MS, Hess AK (1987) Who is the ideal supervisor? Prof Psychol Res Pract 18(3):244–250

De Kleijn RAM, Meijer PC, Brekelmans M, Pilot A (2015) Adaptive research supervision: exploring expert thesis supervisors’ practical knowledge. High Educ Res Dev 34(1):117–130

Deuchar R (2008) Facilitator, director or critical friend? Contradiction and congruence in doctoral supervision styles. Teach High Educ 13(4):489–500

Duxbury L (2012) Opening the door: portals to good supervision of creative practice-led research. In: Allpress B, Barnacle R, Duxbury L, Grierson E (eds) Supervising practices for postgraduate research in art, architecture and design. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, pp 15–24

Dwyer FR, Oh S (1987) Output sector munificence effects on the internal political economy of marketing channels. J Mark Res 24(4):347–358

Farrelly FJ, Quester PG (2005) Examining the importing relationship quality constructs of the focal sponsorship exchange. Ind Mark Manage 34(3):211–219

Fleck ND, Quester P (2007) Birds of a feather flock together… definition, role and measure of congruence: an application to sponsorship. Psychol Mark 24(11):975–1000

Gundlach GT, Achrol RS, Mentzer JT (1995) The structure of commitment in exchange. J Mark 59(1):78–92

Harrison S, Grant C (2015) Exploring of new models of research pedagogy: time to let go of master-apprentice style supervision? Teach High Educ 20(5):556–566

Heath T (2002) A quantitative analysis of PhD students’ views of supervision. High Educ Res Dev 21(1):41–53

Hemer SR (2012) Informality, power and relationships in postgraduate supervision: supervising PhD candidates over coffee. High Educ Res Dev 31(6):827–839

Hockey J (1994) Establishing boundaries: problems and solutions in managing PhD supervisors’ role. Cambridge J Educ 24(2):293–305

Johnson WB (2007) Transformational supervision: when supervisors mentor. Prof Psychol Res Pract 38(3):259–267

Macdougall HK, Nguyen SN, Karg AJ (2014) ’Game, set, match’: an exploration of congruence in Australian disability sport sponsorship. Sport Manag Rev 17(1):78–89

Mainhard T, van der Rijst R, van Tartwijk J, Wubbels T (2009) A model for the supervisor-doctoral student relationship. High Educ 58:359–373

Malfroy J (2005) Doctoral supervision, workplace research and changing pedagogic practices. High Educ Res Dev 24(2):165–178

Moorman C, Zaltman G, Deshpandé R (1992) Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamic of trust within and between organizations. J Mark Res 29(3):314–328

Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 58(3):20–38

Palmatier RW, Dant RP, Grewal D, Evans KR (2006) Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: a meta-analysis. J Mark 70:136–153

Pearson M, Brew A (2002) Research training and supervision development. Stud High Educ 27(2):135–150

Seppänen R, Blomqvist K, Sundqvist S (2007) Measuring inter-organizational trust: a critical review of the empirical research in 1990–2003. Ind Mark Manage 36(2):249–265

Sidhu GK, Kaur S, Chan YF, Lee LF (2015) Establishing a holistic approach for postgraduate supervision. In: Tang SF, Logonnathan L (eds) Taylor’s 7th teaching and learning conference 2014 proceedings. Springer, Singapore, pp. 529-545

Spais GS, Johnston MA (2014) The evolution of scholarly research on sponsorship. J Promot Manag 20:267–290

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank Professor Pascale Quester for excelling in both intellectual and pastoral dimensions of supervision. Both authors would like to thank her for her trust on and commitment to good research practice, and for being the ultimate dancing queen when she gets the chance. The first author was, has been, and will be forever grateful to Professor Quester for being his career and supervisory role model. The second author would also like to thank Dr Shona Crabb—whom he sought as a supervisor because of a congruence in world views that has enriched his approach to subsequent post-doctoral research. We also thank ABBA for putting music to our thinking of the proposed model of supervision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lu, V.N., Scholz, B. (2016). Knowing Me, Knowing You: Mentorship, Friendship, and Dancing Queens. In: Plewa, C., Conduit, J. (eds) Making a Difference Through Marketing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0464-3_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0464-3_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-0462-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-0464-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)