Abstract

The Soviet system of higher education was well developed even in today’s terms. It provided free higher education to a significant part of the young generation. The Soviet government was the first in the world in applying positive discrimination to higher education enrollment to achieve greater social cohesion. The system produced highly qualified personnel for the national economy, especially in such sectors as engineering, health care, and science. At the same time, the higher education system was under tight ideological control and rigidly regulated. All universities operated within strict curriculum standards. The Soviet planning agency regulated supply and demand in higher education. Perestroika that started in the late 1980s changed the system dramatically.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The Soviet system of higher education was well developed even in today’s terms. It provided free higher education to a significant part of the young generation. The Soviet government was the first in the world in applying positive discrimination to higher education enrolment to achieve greater social cohesion. The system produced highly qualified personnel for the national economy especially in such sectors as engineering, health care, and science. At the same time the higher education system was under tight ideological control and rigidly regulated. All universities operated within strict curriculum standards. The Soviet planning agency regulated supply and demand in higher education. Perestroika that started in the late 1980s changed the system dramatically.

The establishment of the Russian Federation in 1991 marked the emergence of a higher education system that in many ways differs from its predecessor. The process of its transformation reflects general patterns of social and economic transition typical of the post-Soviet societies. However, it has some specific features that deserve a thorough analysis. On the one hand, in the past 20 years, Russia has become one of the world leaders in higher education enrolment and on the other hand, it is placed only 50th in the country rankings compiled by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) regarding the country’s higher education and training systems for the knowledge economy, lagging behind both developed and developing countries (see Nikolaev and Chugunov 2012).

The number of higher education institutions has doubled over the last 20 years and the number of students increased 2.5 times, reaching a total of 7 million in 2005. These figures are very impressive in comparison with the 1940–1991 period, when the growth of the number of universities was almost flat. This chapter shows that this expansion was accompanied by significant qualitative changes in the supply and demand of higher education services. It starts from the general description of the higher education system.

We argue that this development has its roots in the history of Soviet higher education. The second section of the chapter discusses this legacy. The third section describes the main institutional changes in the higher education system and the changes in demand that have led to the “great expansionFootnote 1” during the “Modern Russia” period since 1991. The fourth section focuses on the changes in the structure of the supply of the higher education services. The fifth section discusses the role of private higher education. In the sixth section, we consider the impact of increased supply on equal access to higher education.

In the last section, we present recent changes in national higher education policy. We argue that “hidden” changes in the supply and demand should be articulated in the national higher education policy by considering them through the lens of the differentiation of the universities and their ability to respond to labor market demands.

2 General Description of the System

2.1 Scale of the System

The Russian Federation inherited one of the largest higher education systems in the world from the Soviet Union. It was a part of huge tertiary education system that included higher education per se (university level education, both graduate (3-year doctoral program) and undergraduate (4–6-year specialist program opened for the secondary school graduatesFootnote 2)), vocational colleges providing associate degrees (3–4-year program opened for graduates of secondary school graduates and those who completed nine grades in secondary schools), and vocational schools providing qualifications (1–2-year initial vocational education program opened for graduates of secondary school graduates and those who completed nine grades in secondary schools). The flows for students between these levels of tertiary education are shown in Fig. 6.1.

Figure 6.1 shows the main elements of the Russian system of education and flows of students moving between them. It also shows how many new students come to tertiary education and how many graduates go to the national and international labor markets and military service. It is seen that higher education was the biggest part of Russian educational system. In 2010 alone, 1.43 million people with different backgrounds entered universities: 0.58 million people were high school graduates, 0.01 and 0.17 million people finished vocational schools and colleges respectively; 0.57 million people came from labor market or military service.

In this chapter, we consider the system of higher education only. The interaction of higher education system with other subsystems of the tertiary education does not play critical role in the functioning of higher education institutions.

The number of higher education institutions has doubled from 514 universities in 1991 to 1115 in 2011. The private sector played a very significant role in the increase of the number of higher education institutions (Table 6.1), triggered by the shift to a market economy. The number of private higher education institutions increased by six times over the past 17 years and reached 462 in 2011. They try to compete with public institutions but, in many cases, fail in this purpose, and only attract students who fail in the entrance examinations for public universities.

Over the past decade, the budget (public) in higher education, both overall and per student largely increased. In 2003, the allocated funds were about US$ 2 billion whereas in 2010, funding overcame the mark of US$ 12 billionFootnote 3. This money went to public institutions (only in 2011, a few private higher education institutions received public grants for their education programs)Footnote 4.

2.2 Enrolment in Higher Education

The number of students also has risen significantly. On the threshold of Soviet Union disintegration, the number of students was slightly less than 3 million but exceeded 7 million by 2010. That figure includes more than 1 million students in private universities. Today, access to higher education in Russia is seen as very open. Enrolment in higher education has risen dramatically. Eighty four percent of all school graduates wish to continue their education in universities and more than 50 % of people in the age group 17–22 study in higher education institutions as shown in Fig. 6.2.

Gross coverage and enrolment in higher education in the Russian Federation (2000–2010, percent). Figure shows ratio of students studying in higher education institutions to 17–22-year-olds; and ratio of entrants to higher education institutions to 17-year-olds. (Source: Nikolaev and Chugunov 2012)

2.3 The Structure of the System

Today the higher education system in Russia is diversified. It includes education institutions of various legal forms and types. The overwhelming majority of public universities belong to the federal authorities (about 60 % of them operate under the Ministry of Education and others under sectoral ministries like health and agriculture). Fewer than 20 public universities are established by the regional authorities. Private universities exist in the form of nonprofit organizations. They have to get a license from the federal authorities to start operations. They also have to go through the accreditation process (also conducted by the federal body) if they want to issue government-approved diplomas.

Till 2009, all public universities had the same legal status. Recently, the government tried to institutionalize naturally emerging diversity. It established two new prestigious types of universities: national research universities (NRUs) and federal universitiesFootnote 5. In the Soviet period, research activities were concentrated in the specialized research institutes. Now, the government is trying to move the research activities to NRUs, which are expected to be the main sources for scientific development in Russia. Federal universities are established in remote regions of the country to play leading role in the development of the innovation economy in the respective regionsFootnote 6.

2.4 Educational Programs

In 2003, Russia signed the Bologna Declaration, which launched the process of transition from the Soviet degree structure to a modern degree structure in line with the Bologna Process model. In October 2007, a law was enacted that replaced the traditional 5-yearFootnote 7 model of university education (degree of specialist) with a two-tiered approach: bachelor’s degree followed by a 2-year master’s degree. In 2010, the admission to the traditional 5-year program was stopped in the majority of universities. By 2014 almost all students in 5-years programs leave the universities. Today more than half of the students study economics and humanities (Fig. 6.3 and Table 6.2).

3 State Regulation of the Supply and Demand: The Legacy of Soviet Higher Education

Soviet higher education policy was based entirely on the idea of the planned industrial economy. Higher education was part of the resource allocation system that covered manpower resources as well as material and financial resources. According to the Burton Clark’s typology (Clark 1983), the Soviet higher education policy belongs to those types of policies where government has the main organizational role and the education market does not exist. At the same time, higher educational institutions have a low level of institutional autonomy and the system has a high degree of centralized management. We think that the Soviet system (and in general, higher education systems in socialist countries) was an extreme version of the government-controlled system and probably presented a special type of the system. We call such a system of higher education, “quasi-corporate” (Froumin et al. 2013) because the higher education institutions were parts of particular industries. Indeed, during the Soviet regime, the government was both—the main owner of universities and the main employer. The main role of government in the economic sphere was the input and output planning. In higher education, this would imply planning the number of students, specialties, and programs for each institution based on the needs of different industries. In other words, the development of the higher education system depended on an estimation of the national needs of the labor force (Shpakovskaya 2007). It is important to note that universities in Moscow and some capitals of the former Soviet republics were providers of the manpower for the national labor market whereas regional universities had the same function for the local labor markets.

The role of the higher education institutions as manpower suppliers for particular sectors of economy and even for particular enterprises is deeply rooted in the industrialization of the Soviet economy in the 1920s. In this period, the Soviet government relied mostly on the technological expertise developed in western countries and on a mass higher education model (Khanin 2008).

Each important development in the national economy as well as in social and political life was accompanied by a corresponding development in the higher education sector. For example, after the Second World War, the government set up “communist party schools” for training party apparatus and state machinery. Besides, the Academy of Social Sciences was established for training ideologists and social scientists. These institutions had the status of universities. Special institutions were set up for training specialists in diplomacy and foreign trade. Soviet nuclear production and space development programs led to the establishment of two elite universities: Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology and Moscow Engineering Physics Institute (Khanin 2008) and quite a few engineering universities and departments specialized in nuclear physics and space research.

However, the above postwar changes and those introduced during the Khrushchev era did not involve a significant change in the structure of the higher education system, which was formed mainly in the 1930s (Shpakovskaya 2007). Figure 6.4 illustrates an insignificant increase in the number of universities since the end of the 1940s till the collapse of the USSR.

We agree with the statement by Carnoy et al. (2012) that the Soviet totalitarian state considered the provision of higher education as an important factor of legitimization of the state. However, the most important factor that determined the supply of the higher education in the USSR was not students’ and families’ desire for personal development or social mobility through higher education but the requirements of different sectors of the Soviet economy. This demand focused mainly on the manpower for these sectors. The demand for research and development (R&D) for these sectors was divided between the higher education institutions and special R&D organizations (including academies of sciences).

The Soviet government invented a number of instruments to align supply and demand in the system. These instruments include: manpower planning and forecasting; state orders to each university to produce a certain number of graduates in different and very specialized areas (there were more than 400 specializations planned by the central planning authorities in 1971); mandatory job placement for each graduate with the requirement to spend at least 3 years in the assigned job; mandatory links between state-owned companies (there were no other companies) and universities that included on-the-job training and mandatory contracts for R&D. The system had a built-in mechanism to respond to the future needs of the economy: the development plans for new industries included such special measures as the development of new occupational requirements, appropriate curriculum and teaching materials, and opening new programs and whole institutions.

As we consider the manpower production (and partially R&D) for different sectors of economy as the basis for analysis of the structure of the supply of the higher education, we suggest that the Soviet higher education system included the following types of higher education institutions:

-

sectoral universities of national significance;

-

sectoral universities of regional scale; and

-

“traditional” universities aimed at training local and national elites.

The first type—national sectoral (specialized) universities—was a Soviet type of corporate higher educationFootnote 8. It included universities of aviation, railways, and mining. Each group of sectoral universities included a “central” sectoral university that played a role of a leader for the whole group. It produced cadres of professors for other sectoral universities; central sectoral universities had significant programs of R&D in the particular sector. Other sectoral universities usually were connected with particular enterprises within this sector in different regions of RussiaFootnote 9. It is important to mention that many such universities were subordinated to sectoral ministries rather than the Ministry of Education of the USSR.

The reason for the existence of the second type of Soviet higher education institutions was the need for training the personnel for specific sectors of the regional economic systems. These institutions were regional sectoral universities. The higher education institutions with such disciplines as education, culture and arts, medicine, engineering, agriculture, and finance were established in each region or in the group of neighboring regions (the central planning agency had special procedures to allocate different specialized universities among the regions). In some cases, these institutions were subordinated to particular sectoral ministries (e.g., agricultural higher education institutions to the Ministry of Agriculture, medical higher education institutions to the Ministry of Health Care, and teacher training (pedagogical) higher education institutions to the Ministry of School Education). Each sectoral group of the regional higher education institutions also included central or leading institutions in Moscow or in other capital cities. These leading institutions performed the functions of methodological support and knowledge management within the specific group (e.g., the First Moscow State Medical University or Russian Teachers’ Training University in Leningrad). All universities in the regions of Soviet Russia were subordinated to the central authorities in Moscow.

The third type—traditional universities—performed two functions. They trained: (1) researchers that moved them to the R&D sector or to other universities as professors (especially in departments of basic sciences, social sciences, and humanities) and (2) local (and in some cases—national), managerial, and political elites (economics, history, law, journalism, etc.). As a rule, these universities did not have schools of engineering, arts, and medicine. This structure fits well with the structure of the Soviet labor market. A rigid regulatory framework for different types of institutes was developed centrally. The initiative from the bottom was not welcomed. However, the fact that the Soviet government used effective mechanisms of turning universities into resources of the national and regional planned economy cannot be denied. The state system provided the higher education with the resources adequate for the demand formulated by the state-owned and state-controlled economy. The problems of this system reflected general problems with a centrally planned economy: rigidity and lack of initiative and built-in feedback.

It is important to clarify that legally all universities had the same structure of programs: undergraduate and graduate. Almost all programs were planned for 5 years of implementation (with very few exceptions). There was a small group of universities that included research centers with separate financing. These universities had larger graduate programs than other universities. However, formally all diplomas had the same value. Students from sectoral universities could enter graduate programs and research careers in the respective sectors.

The relationships between universities and research institutions (including academies of sciences) were also formalized. The majority of leading researchers from the research institutes worked part time as professors in local universities (often there were heads of departments). Many research institutes had their own doctoral programs. They cooperate with the universities to get the applicants for these programs. So, both supply and demand in Soviet higher education came from the government.

At the same time, the government could not completely ignore demands from families (and the students). Students could choose a university and program to study. They could enter the chosen university through competitive exams managed by an individual university. One could imagine the system that extends the planning to the selection of the students to enter the universities. In such a “brave new” system, the government should test the appropriateness of school students to the particular job and place them into the respective universities and programs. To some degree, such an approach was tested in various forms in early Soviet times. In the last Soviet period, the government used different forms of positive and negative discrimination to regulate the students’ demand for higher education. Special places in universities were reserved for young people with working experience in a particular sector and for students from ethnic minority groups. They could get into the most prestigious universities with lower exam results within the special quota.

4 Social and Economic Transition and the Expansion of Higher Education over the Last 20 Years

The Russian higher education system was strongly affected by the social, cultural, and economic changes that have been taking place in the country since the beginning of the 1990s. The key changes and characteristics of this period relevant to tertiary education as indicated in OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education (2007) were the following:

-

movement to democracy and market economy;

-

rejection of planned human resources policy related to the main economic sectors;

-

decline or elimination of a number of key industries;

-

elimination of the centralized distribution system; and

-

dramatic weakening of centralized control.

Changes that happened in the Russian labor market as a result of the “perestroika” are also important. These changes were a swift shift from state control of wages, manpower resource allocation, and employment to a market system of wage setting, students’ response to labor market opportunities through the choice of courses and programs, and freedom of employers to hire graduates based on market conditions (Carnoy et al. 2012). In the section below, we analyze how social and economic transformations affected the demand for higher education.

New sectors of the economy emerged with unprecedented speed—e.g., banks, insurance companies, and private retail. They required hundreds of thousands of managers, accountants, and lawyers trained for the new economy. At the same time, many traditional industries collapsed. The salaries of engineers and researchers (especially in natural and engineering sciences) decreased. This new demand of the labor market mirrored the changing preferences of families and students. They turned to business education and departments of management, economics, law, and humanities (The White Book of Russian Education 2000). The dramatic shift in the preferences of prospective students became one of the determining factors in the expansion of higher education.

However, we argue that strong demand for higher education from families and students themselves was not determined by the changes in the labor market structure only. This demand existed implicitly for a long time in the Soviet Union. The voices of families and students were not heard. Many educated and caring families could not send their kids to universities because of the high competition, tight limitations on the number of places, and the government discrimination instruments. The emergence of new stakeholders in consumers of higher education services was the most important factor in higher education expansion. The “quasi-corporate” system suddenly became an open market system. Another important driving force behind the male students’ wish to enter a university was the avoidance of the Russian army draft. As soon as a male becomes a student, he gets a draft exemption.

As it happened with some other previously closed and heavily regulated areas of the Soviet life, the opening of the higher education sector to the demand of new stakeholders led to massive growth. The government did two things to open the system to new customers. In 1992 it permitted public institutions to enroll fee-paying students along with state-funded students and allowed the opening of private higher education institutions. It also added a number of state-funded places to the public universities, but the main expansion happened because of fee-paying students as is shown in Fig. 6.5.

School graduates and admissions to universities: 1998–2009 (thousands). (Source: Nikolaev and Chugunov 2012)

This coexistence of tuition-paying and tuition-free places at the Russian public universities is a relatively unusual phenomenon. Different universities employ different strategies to resolve inevitable tensions associated with this arrangement. There are no studies of the impact of this coexistence. Anecdotal evidences and informal interviews with the university rectors show that all universities found ways to put together these two cohorts of students. Another question arises: where do the Russian public universities get the capacity to absorb all these students—where do they get professors, laboratories, learning materials, etc.? The answer is that they started to utilize the existing capacities more effectively. However, this is only a part of the answer. Two main trends behind the capacity increase were acceleration of part-time programs and opening of branches of universities in different cities and towns. The provision of part-time education increased so quickly that in 2000, the admission to universities exceeded the number of school graduates (Fig. 6.6).

This “excessive” supply reflected the growing demand by other audiences not just school leavers. This is why the supply included such options as shortened programs that provided a “second diploma” for those who completed higher education program before and part-time education for those who graduated from vocational schools or vocational colleges (with associate degrees). As a result, the share of part-time students in Russia was more than 50 % as of 2010 according to “Education at a Glance 2012” (Table 6.3).

University branches grew very quickly. Often they were opened in small towns with poor quality buildings, without any human capacity to teach. However, it did bring higher education (we do not mention the quality of education here) to the consumers. In 2002, there were more than 1300 branches of public universities in all regions of Russia. Most of the places in these branches were self-financed.

The second most important response to changing demand was the development of the private sector in Russian higher education. More than 450 private universities have been opened over the past 20 years. The private sector in higher education is of particular importance for the post-Soviet period being reviewed—discussed further in a separate section. As a result, the number of higher education institutions in Russia grew rapidly (see Table 6.1). A few new public universities were also established by the federal and regional governments to respond to the changing demand.

The growing supply in higher education gradually influenced the demand and supply of professional education on other levels: initial and vocational colleges (UNESCO levels 4 and 5b). From 1991 to 2010, the number of students in initial vocational programs dropped from 1.8 to 1 million whereas the number of students in vocational colleges remained mostly stable (as illustrated in Tables 6.4 and 6.5).

The enormous expansion did not just respond to the existing unsatisfied demand; the supply also fueled the demand back starting the cycle of mutual stimulation. Higher education had become a social norm for young people. Currently 85 % of secondary school graduates (supported by their families) plan to enter higher education. They consider higher education not just a pathway to specific occupations but as a means to acquire general competencies and a social status.

Compared to the Soviet times, the government significantly reduced its role in regulating the access to higher education institutions. The affirmative action policies were mostly stopped. The introduction of the national, centrally administrated university entrance exam (the so-called Universal State Exam (USE)) was the major policy step to ensure nationwide competition for university places. However, a number of universities (especially those that operate under the sectoral ministries) have a special quota for the students that “are sent” by particular state-owned companies to study at these universities with some guarantees of employment. However, the number of such students is very low compared with those who enter the universities through USE.

5 Changes in the Supply Structure of Higher Education

The data in the previous section suggest that in the past 20 years, Russia has achieved a very high degree of access to higher education. In the section below, we discuss how this expansion has changed the structure of the higher education system and how the system has responded to the structural changes in the economy and, specifically, in the labor market. These dramatic changes were accompanied by the deconstruction of the existing instruments of aligning supply and demand. The government abandoned the centralized mandatory graduates’ placement system. This happened overnight. Tens of thousands of graduates found themselves in the labor market without any guidance, support, and recruitment infrastructure. The carefully built balance between supply and labor market demands was broken.

The situation in Moscow and Saint Petersburg is a good example of the mismatch that emerged. By 1991, 23 % of all public universities and more than 25 % of students were concentrated in Moscow and Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) with 28 % of teaching staff being located in those cities, i.e., nearly 32 % of the total number of teachers holding academic degrees worked in those cities (The White Book of Russian Education 2000). Before 1991, the majority of the university graduates in Moscow or Leningrad used to be sent to other regions through the mandatory job placement mechanism. They could not stay in Moscow and Leningrad legally. After the abolition of that mechanism, the majority of the university graduates of those cities decided to stay in the capital cities despite the fact that the labor market did not need such large numbers of aviation engineers or medical doctors.

Almost all the links between universities and industry previously enforced by the central planning agency disappeared. However, the government maintained one function—the allocation of budget-financed student places among different universities and educational programs within universities. Despite significant changes in the Russian economy and in the labor market, this allocation (that formerly presented the needs of different elements of the economy) did not change much. New needs of private business, families, and students themselves did not find an adequate response from the government in the form of allocations of state-funded places. The changes in the structure of the supply of the state-funded places were slow and insignificant. This fact confirms the path dependency theory (David 1985) as the universities did not react to the changing labor market. They continued to ask the government to finance the same narrow training of the specialists that they had done for many years. They were interested in maintaining the state of affairs to avoid investment in such changes. Thus in their relationship with the state, the universities tried to maintain the traditional set and volume of educational programs paid by the state despite the real needs of the labor market.

Traditional employers (especially big state-owned companies) were reasonably happy with the traditional structure of the supply. Gradually, the voice of new players or stakeholders—private business in new industries—became louder. Employers in new emerging industries required not only general managerial and social skills but also strong technical skills e.g., information technologies skills. The universities had neither trained personnel nor developed curriculum to provide training for the emerging sectors. The Ministry of Education did not hear this voice and maintained a rigid approach to the federal education standards. This became a barrier to increasing universities’ flexibility in responding to the changes in labor market demands.

As demonstrated by and Dobryakova and Froumin (2010), there are no real incentives for universities to abandon outdated programs, improve the quality of their educational provision, and introduce innovation. University administrators, professors, and even students are more or less satisfied with the current state of affairs. Russia maintains a very low level of unemployment and at least “some work” is guaranteed to the graduates. This allows students to ignore professional training and focus on developing social competencies. According to a recent survey of 890 employers in Russia, less than 10 percent of the employed found jobs in the industries fully corresponding to their specialization as stated in their diplomas. The research also indicated that 75 percent of university graduates in Russia have been taking jobs in the areas different from their fields of study and most of them have to receive some on-the-job training prior to cope with job responsibilities [Galkin, 2005].

At the same time, in their response to the popular demand for training in management and economics, marketing universities opened new schools and departments mainly on a fee-paying basis. The departments of economics, management, law, etc., started getting established almost in all universities including formerly highly specialized institutions. This led to significant changes in the structure of the supply of higher education as shown in Fig. 6.7.

Admission to higher education institutions by groups of specialties. (Source: The White Book of Russian Education 2000)

This analysis demonstrates that universities responded quite effectively (at least in terms of quantitative expansion) to the demands of families and students for managerial, economic, and legal education. This was also a response to the demand of the emerging service sector of the Russian economy. The specific nature of this situation is that both the creation and the expansion of the service sector in the Russian economy and the higher education response took place almost simultaneously. The sector representatives did not have the capacity to articulate their demand and to formulate the requirements to the quality of training. The demand for quantity was so high that the universities could ignore the quality. They had almost no trained staff to teach students. They had no proper textbooks and teaching/learning materials. This is one of the reasons why this sector of Russian higher education is still regarded as a low-quality sector. So, on the one hand, public universities tried to keep the status quo in their “traditional” fields and to maintain the allocation of the state-funded places in these fields. They considered the state as an important consumer. On the other hand, they found new market-type demand for economics and management training by prospective students and responded to this demand. So in both cases, they behaved rationally.

The expansion of education in “soft areas” such as management and business indicated the desire of the students to obtain flexible and broad education—not just new labor market opportunities. Almost all stakeholders complained about too narrow specializations and the vocational orientation of the higher education. The Ministry of Education responded slowly by cutting down the number of specializations from 1200 in 1997 to 900 in 2003. Radical change started with Russia joining the Bologna process in 2003. The majority of the 5-year specialized programs were merged into a broader 4-year baccalaureate programs. This led to the significant change in the structure of the supply of the higher education. It also contributed to saving resources by shortening the majority of programs by 1 year.Footnote 10 These changes in supply led to the change of the typology of the universities described in Sect. 6.2.

National sectoral (specialized) universities became more diverse. They opened new programs in economics and management. However, their progress or stagnation much depends on the situation in the “parent industry.” In the case of the degradation of the sector with automotive production, textile industry and electronics being good examples, the labor market shrinks and becomes unattractive. Graduates will not find jobs according to their specialty. Even if the sector survives, the capacity of universities producing such specialists easily becomes excessive as it has happened to a network of universities that served the aviation industry. Thus, these universities enter unhealthy competition. By maintaining their sectoral identity, they face the risk of stagnation. They get fewer good students and less funding for research or fee-based specialized training. In the case of the progress of the sector (oil and gas industry and railways), the universities also retain their identity but develop new programs reflecting new challenges and opportunities in the sector. They develop R&D partnerships.

The second type of universities—regional-sectoral universities—went through dramatic changes. Their parent industries declined in most cases. They opened departments of management, economics, and psychology, for example. This made them direct competitors to each other and to “traditional” universities. Most of them, with the exception of medical universities, became outsiders in the national and regional higher education systems. They refused to cut enrolment and were faced with the intake of low-qualified students. Having the status of federally governed institutions, they have not established new relationship with the regional authorities and regional labor markets. Some exceptions rather confirm the general rule—those universities that do not provide special education do not have any real value in relation to the labor market. At the same time, they play an important role by giving general social skills to the students.

Finally, traditional universities mostly maintained their status of leading higher education institutions in their regions. They had an advantage of having some capacity in training economists, journalists, and lawyers. In most cases, they continue to train local elites. But the decline in research funding in the country dramatically affected almost all departments, particularly science departments. The best professors left the universities and often left the country. Due to the decline in funding, the research function in those universities has almost disappeared. They also stopped training specialists for the Academy of Sciences and for the sectoral research institutions.

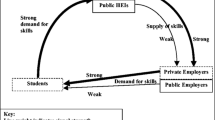

Thus, currently Russia has a new structure of higher education. It is much more diverse than it used to be in the Soviet Union. The state has lost the instruments to maintain the traditional balance between the supply and demand and maintain the quality at a reasonable level. The state has not introduced new market-based instruments to ensure entrepreneurial behavior of the higher education institutions, their openness to the labor market demands, and to the expectations of the external stakeholders (OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education 2007). The current structure of supply does not match these demands and expectations.

6 The Development of the Private Higher Education Sector in the Last 20 Years

There used to be no private education in the Soviet Union. The education law of 1992 allowing the establishment of private higher education institutions was met with unexpected enthusiasm. Since then, a number of private universities have been providing education in socioeconomics and humanities. Private universities made attempts to be more open to potential candidates and their parents and respond to the requests of the rapidly changing educational market. But in pursuit of meeting these needs, they face contradictory needs: some consumers were longing only for diplomas; other candidates were seeking skills that were in demand in the labor market; many parents wanted to keep their childrenFootnote 11 out of the labor market and give them general social skills and functional literacy. The majority of researchers argue that the “private sector initially failed to perform creatively in a competitive environment” (Gurov 2004). We do not agree with this statement. Indeed, there are almost no private universities in Russia that offer free education. So each private university has to raise funds from students and attract as many students as possible. At the same time, the objective view suggests that there are three main types of private universities based on existing demand. For those universities that “sell diplomas,” the quality of education is out of their list of priorities. Other universities keep kids out of the streets and provide them with basic managerial skills. As the leader of one of such universities claimed, “primarily private universities were established as a sort of employment agency to prevent young people from becoming unemployed and committing crime” (Ilyinsky 2004). Finally, there is a group of private universities that provides decent training in such areas as law, management, and business. Figure 6.8 shows that the private universities are focused more on part-time education than the public universities.

During the last 20 years, private universities (with few exceptions) failed to become central players in the market for higher education. They are perceived by the population and by the state as marginalized group of universities for those who cannot get free tuition places in public universities. It means that if a school leaver fails to get a tuition-free place in a public university and, at the same time, cannot afford to pay for his/her education because the tuition fee in public university is much higher than in private universities, he/she has an option of a private university.

The data collected by the Higher School of Economics (RIA News 2012) demonstrate that the average USE score to enter private universities in Moscow is only 55.1 points whereas in public universities, it is 69.5. Such a distribution is also typical for other regions in Russia. The majority of private universities enroll 2/3 of their candidates with an average score between 47 and 55 points. Only 1/3 of the candidates enrolled by state universities have scores under 45 points whereas 62 % of private universities accept candidates with a minimal score under 45 points. Current demographic trends suggest that the private universities are facing the growing challenge to obtain students. It pushes them to work more with nontraditional students and become institutions for life-long learning.

7 Access to Higher Education

The sharp drop in income levels and living standards after the collapse of the Soviet Union affected the accessibility of higher education for different population groups. Many parents were not financially sound to send their children to other cities to prepare for and pass the entrance examinations of the universities. Such a situation did not allow well-prepared school graduates from rural areas or far regions to enter the best universities. They had to choose higher education institution according to territorial proximity. Financial factors began to be assumed as definitive criteria for admission to universities, as claimed by Efendiev and Reshetnikova (2004). Residence and income level had a significant impact on access as many experts believe. This situation was perceived by the population as a serious injustice because, as we mentioned earlier, the Soviet system included a number of measures of positive discrimination (affirmative action) that equalized the access to higher education for different income groups despite their place of residence.

Corruption at the entry point to university was another serious problem that affected equal access to higher education. Corruption existed at the level of individual examiners as well as at the institutional level. Each higher education institution had its own entrance exams to be passed, which usually required additional training. Applicants wishing to get to specific universities could hardly expect successful enrolment without completing these very expensive preparatory courses. The corruption in university entrance exams processes was widespread.

The introduction of the USE in 2009 was an important step to get rid of corruption and improve the access to higher education. OECD experts claimed, “the development of a new form of enrolment - based on the Unified State Exam - is the most important and fundamentally new initiative in recent years aimed, on the one hand, at equalizing the territorial and economic differences and on the other hand, at eliminating institutional barriers that arise due to the gap between institutions of secondary and higher education.” (OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education 2007).

The introduction of the USE almost stopped the corruption. It widened the choice of universities. Thus, the USE has increased the accessibility of education by reducing the transaction costs associated with preparation for entry. Also, conditions to enhance educational mobility of students were created. Some examples of the USE influence on access to higher education should be noted. The number of students of the Higher School of Economics from different regions of Russia increased steadily as a result of the USE (Fig. 6.9).

Regional distribution of 1st year students at HSE.) (Source: NRU 2009, http://ba.hse.ru/stat

Currently, most of the best and brightest school graduates from the Russian regions use the USE to enter the best universities in the Moscow. It created new demand for places in the reputable universities and stimulated stronger competition among capital and regional universities for the best students. One cannot claim that the introduction of the USE solved the problem of access to high quality higher education. The cost of living in capital cities is still unbearable for many families. The state failed to introduce working schemes of financial assistance for the students from poor families. Difference in the level of preparation of school graduates to the USE is also an important factor that limits the opportunities of students that did not go to good schools. A number of studies confirm the fact that students from families from the two lower-income quintiles are represented disproportionally low in top Russian universities. This issue needs to be addressed.

8 New Higher Education Policy: From Access to Quality

The National Education Development program was approved by the Russian Government in December 2012. It marks a new stage in educational reform in Russia and reflects experiments that took place in Russian education in last 5 years. The quality of education is considered in this program as a priority for educational policy. In higher education, quality is interpreted as strong correspondence between the demands of the labor market and the supply of educational servicesFootnote 12. The idea of quality also includes such aspects as international competitiveness that often is seen through the lens of international rankings. This section describes various reforms that are intended to lead to better quality higher education.

8.1 The Establishment of a Group of Leading Universities

The government recognized the need to articulate the differentiation of universities and give better opportunities to some universities to become leaders and beacons for other universities. Two groups of universities were established:

8.1.1 Federal Universities

The process of creating a network of “federal universities” in different regions by merging existing higher education institutions started in 2006. The main goal of establishing these universities is the development of strong higher education institutions that could become drivers for regional economic and social development through advanced R&D and the provision of world-class education for the students from remote regions. Federal universities had to comply with several important features described as follows:

-

A wide range of innovative higher and continuing professional education programs, retraining and advanced programs based on the use of modern educational technologies and differentiation by target group and levels.

-

A wide range of fundamental and applied interdisciplinary research including priorities for the development of science, technology, and engineering in Russia.

-

Participation in regional, national, and international programs and projects to provide sustainable diversified revenue structure in consolidated budgets of the university.

As a result, nine federal universities were created all over the country, from Kaliningrad to the Far East over the past 7 years. Each of these universities received an additional development grant to improve the infrastructure for teaching and research. The total funding of these development grants exceeded 90 billion rubles (about 3 billion dollars). However, the impact of this project is doubtful. The selection of higher education institutions for the status of the federal university occurred without any contest. It was held according to geopolitical considerations and also under lobbying efforts undertaken by regional leaders. So the capacity of these universities was insufficient to achieve the stated goals. Moreover, the government did not realize the pitfalls of merging different institutions. Such a situation raises questions about the achievement of stated objectives: it was assumed that the federal universities would be among the top 300 best universities in the world by 2020.

8.1.2 National Research Universities

An open contest was held by the Ministry of Education and Science for granting the status of a NRU in 2008. The NRU status was assigned to 29 higher education institutions through two rounds of the competition (the second round took place in 2009). The integration of education and research is the main feature of these universities. NRU status is aimed at new knowledge generation and transfer; conducting fundamental and applied research. Obviously, these features affect the educational process—a significant proportion of students enrolled in graduate and postgraduate programs.

The universities that become the winners received additional funding (up to 1.5 billion rubles for 5 years), which could be spent on [Decree No. 550 2009]:

-

purchase of educational and scientific equipment;

-

professional development and retraining of academic and teaching staff;

-

development of educational programs;

-

development of information and communication technologies (ICT) resources; and

-

improvement of the quality of education and research management.

The additional funding helped to improve the infrastructure of the universities and the professional development of teaching staff. Unfortunately, these formally prescribed lines of funding did not permit spending money on development of cutting-edge research by attracting the best foreign and domestic faculty. A very important fact is that the new status given to the universities was accompanied by a considerable increase in bureaucratic control. For example, NRUs were supposed to provide weekly reports (Fedukin and Froumin 2010).The idea of the selection and support of universities that are capable of becoming leaders and engines of education mostly had a positive response among the professional community. Other universities began to create development programs to promote research and publication activities following the leaders. The development of these leading research universities should respond to the demand of a national innovation system and the best graduates of the Russian school system that are interested in an academic career. Annual reviews of the outcomes of this project showed the increase in the research output of these universities, strengthening their prestige among the best school graduates.

8.1.3 Project 5/100

In creating the group of leading universities, the Russian Government paid special attention to the Russian higher education acceptance in the international arena, in particular, national universities places in international rankings (The Edict of the President of the Russian Federation 2012). The Ministry of Education identified several tasks to achieve the objective of ensuring that at least five Russian universities are ranked in the top 100 of one of the leading international rankings by 2020. These tasks are:

-

creation of favorable conditions to link research and education;

-

increasing the number of foreign students and postgraduates;

-

attraction of foreign professors and the internationalization of all areas of education and research activities;

-

implementation of international management practices and the involvement of foreign experts in the field of university management; and

-

university brand promotion activities on the world stage.

The contest for the “international competitiveness” grants was planned for the end of 2013.

8.2 New Links Between Universities and Industry

In its attempts to build new mechanisms to link universities and industries, the Russian government moved from direct administrative pressure to market-type incentives. The mechanism was designed to encourage the use of production capacity of the enterprises of Russian higher education institutions for the development of high-tech industry and to stimulate innovation in the Russian economy [Decree No. 218 2010]. Implementation of the decree assumes the possibility of financing projects to the amount of 100 million rubles per year. In this case, an essential condition is a manufacturing enterprise investing its own funds in the project in the amount of not less than the full amount of the government subsidy. The project already has considerable positive results (Kommersant 2012): in 2012, 2488 new jobs were created, including jobs for young people—1484. Projecting for 2013–2017, about 9500 new jobs will be created. The number of young university scientists (experts), students, and postgraduates involved in the research activities of the project amounted to 4319, and among them, young scientists—1733; students—1868; and graduates—718. Another positive outcome of this project was the involvement of the employers in the modernization of the curriculum. It should lead to a better balance in the supply of higher education and high-tech industry demand.

8.3 Closing Down Low-Quality Higher Education Segment

There was a great resonance in expert and professional communities drawn by the higher education institutions’ performance monitoring exercise. It was organized by the Ministry of Education and Science in the second half of 2012. Every public higher education institution and all branches provided data on their performance on 50 indicators. Further, five indicators were singled out and on the basis of data analysis, thresholds of effectiveness were established.

Universities were recognized as “having risk to be ineffective” if four or five indicators were below the threshold. Almost 106 of 502 higher education institutions and 450 of 930 branches got into this group. The result of the additional analysis carried out by government expert groups showed that 25 universities and 231 branches should be closed down and 50 universities should implement serious measures to improve quality. By the end of 2012, 21 universities and 156 branches were closed down or merged with other more successful universities. This measure was carried out to identify underperforming universities that provoked strong public response: some experts believed that drastic action is long overdue and purification of higher education system is essential for its future development. Other groups actively protested and accused the government of destroying a great Soviet legacy. This project indicates that Russian government officials are serious about radical measures to eliminate weak universities. Some estimates suggest that as much as 20 % of universities and 30 % of affiliates would be cut in the next 2–3 years.

9 Conclusions

The last 20 years have radically changed the relationship between supply and demand in the Russian higher education. There were two stages in this change. From 1991 to 2000, the subordination of higher education to the planned and regulated demand of the state controlled economy has been spontaneously transformed into a strange mixture of public provision of traditional education (that almost lost real demand) and a market-oriented supply of popular programs (in economics, management, etc.). New mechanisms to align the supply with demand of the different stakeholders were gradually developed and introduced during the last decade. It happened in the context of a rapid expansion of higher education in Russia and rapid demographic decline of the student-age population. This experience shows that Soviet-type approaches to regulate the supply directly from the center to align it with the demand of multiple stakeholders in a rapidly changing environment do not work. The state should ponder more autonomy to universities and incentives to be more open to different types of demand and to engage universities in healthy competition. At the same time, the state should provide incentives and facilitate the differentiation of universities in response to the diverse demands of the families and the labor market. Finally, another important role of the state in the transition period should be to maintain quality assurance mechanisms by engaging universities in the dialogue with employers, students, and regional authorities.

Notes

- 1.

We thank Professor Martin Carnoy (Stanford University) for this expression.

- 2.

Russian secondary school has 11 grades.

- 3.

Nominal values.

- 4.

New education law allows private universities to compete for public funding with public institutions.

- 5.

Moscow and Saint Petersburg state universities by law have special status of the universities of special significance.

- 6.

These types of universities are described in greater details in the Sect. 6.7.

- 7.

In some areas, 4 and 5.5 years.

- 8.

Soviet sectoral ministries were in some sense, large state-owned companies.

- 9.

Soviets invented the model of “university-factory” where students combined training and getting practical experience from real work. They started from low-skilled jobs in the particular enterprise and moved to higher skilled positions at this factory or plant during 5 years of education. It was considered as full-time education of special sort.

- 10.

We have to admit that, gradually, the Bologna system has affected other sectors as well.

- 11.

It is important to note that the school leaving age in Russia is less than in many countries—17 years.

- 12.

This interpretation of quality looks narrow. It is still a subject of professional discussions.

References

Abankina, I. (2012). Economic results of higher education re-structuring in Russia.

Arefiev, A. (2007). Russian universities on the international education market. Moscow: Center for Social Forecasting.

Burton, C. (1983). The higher education system: Academic organization in cross-national perspective. Oakland: University of California Press.

Carnoy, M., Loyalka, P., Androushchak, G., & Proudnikova, A. (2012). The economic returns to higher education in the BRIC countries and their implication for higher education expansion. Moscow: National Research University Higher School of Economics.

Carnoy, M., Loyalka, P., Dobryakova, M., Dossani, R., Froumin, I., Kuhns, K., et al. (2013). University expansion in a changing global economy: Triumph of the BRICs? Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

Dobryakova, M., & Froumin, I. (2010). Higher engineering education in Russia: Incentives for real change. International Journal of Engineering Education, 26(5), 1032–1041.

Education in the Russian Federation: 2012 – M.: National Research University “Higher school of economics”.

Efendiev, A., & Reshetnikova, K. (2004). Social aspect of USE: Expectations, reality, institutional consequences. Education Issues, 2, 12–35.

Federal State Statistics Service Data. (2012). http://www.gks.ru. Accessed 25 Jan 2013.

Fedukin, I., & Froumin, I. (2010). Russian flagship universities. Pro et Contra, 3, 19–31.

Froumin, I., Kouzminov, Y., & Semenov, D. (2013). Voznikayuchaya struktura vyshego obrazovaniya v Rossii (Emerging structure of higher education system in Russia). Voprosy obrazovania (Educational studies). (2) (in print).

Galkin, I. (2005). “Diploma as a Burden.” Russian business magazine N 18.

Gurov, V. A. (2004). Education quality in private universities. Higher Education in Russia, 6, 148–152.

Ilyinsky, I. M. (2004). Private universities in Russia: Experience of identity. Moscow: Moscow University for the Humanities.

Khanin, G. (2008). Higher education and Russian society. Russian Economic Journal, 8, 75–92.

Nikolaev, D., & Chugunov, D. (2012). The educational system in the Russian Federation, Educational Brief 2012, World Bank Study.

NRU HSE Admission Committee Report. (2009). http://ba.hse.ru/stat. Accessed 28 Jan 2013.

OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education. (2007). Country background report for the Russian Federation.

RIA News. (2012). Salary’s expectations navigator. http://ria.ru/ratings_academy/20120920/712802373.html. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

Shpakovskaya, L. (2007). Higher education policy in Russia and in Europe (pp. 157–163). St. Petersburg: Norma.

Statistics of Russian Education. (2013). http://stat.edu.ru/. Accessed 23 Jan 2013.

The Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 218. (2010). http://p218.ru/catalog.aspx?CatalogId=728.

The Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 220 at 09.04. (2010). Measures to attract leading scientists at Russian higher education institutions.

The Edict of the President of the Russian Federation of May 7, 2012 No. 599. (2012). About measures for realization of a state policy in the education and sciences.

The Modernization of the Professional Education. (2012). http://www.kommersant.ru/doc-rss/2062654.

The official website of the Ministry of Education and Science. http://минобрнауки.рф/новости/2906. Accessed 23 Jan 2012.

The results of research project “Public Monitoring of Freshman Admission at the RF Universities as a Necessary Condition to Support the Equal Access to Education”. http://vid1.rian.ru/ig/ratings/rezultati.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2012.

The Russian Federation Government Decree No. 550. (2009). About the competitive selection of university’s development programs assigned as National Research University.

The White Book of Russian Education. (2000). М.: MESI, 2000, series The TASIS project “Education Management”, part 1, 344. http://ecsocman.hse.ru/text/19153933/.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Oleg Leshukov and Mikhail Lisyutkin for useful discussions and their help with the data processing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Froumin, I., Kouzminov, Y. (2015). Supply and Demand Patterns in Russian Higher Education. In: Schwartzman, S., Pinheiro, R., Pillay, P. (eds) Higher Education in the BRICS Countries. Higher Education Dynamics, vol 44. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9570-8_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9570-8_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9569-2

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9570-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)