Abstract

This chapter investigates patterns of contraceptive use among Australian women who are at ‘risk’ of pregnancy: that is, women of reproductive age who are sexually active. The aims of this chapter are to determine how women control their fertility, and how contraceptive use varies over the reproductive life course. There are many factors that are associated with contraceptive method use to prevent or delay pregnancy. Availability and access to methods is an important consideration, and the chapter starts with an overview of the contraceptives available in Australia, from the most popular through to the lesser-used methods. Contraceptive method use in Australia is also compared with a number of other countries. Method use is then compared for different sections of the population. Important factors that have been found to be associated with contraceptive method use include age, partnership status, education, religiosity, family size (number of children ever born), and fertility intentions. An emphasis is placed on the type of method used and the timing of fertility intentions. This chapter uses information on contraceptive method use and fertility intentions collected in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey as part of the Generations and Gender modules in 2005, 2008 and 2011.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

7.1 Introduction

As succinctly expressed by Frost et al., the ‘average (American) woman – who wants two children – spends about three decades trying to avoid pregnancy and only a few years trying to become or being pregnant’ (2008, p. 1). No doubt this phrase adequately describes the situation of Australian women, or women in any Western-industrialized country. In this chapter we focus on women’s use of contraception for preventing births, by comparing Australian women to women from other comparable countries, and by investigating the factors that predispose the choice of method.

Recent Australian studies have shown that the most popular contraceptive method is the contraceptive pill (Gray and McDonald 2010; Richters et al. 2007; Yusuf and Siedlecky 2007). Condoms are the next most commonly used, followed by vasectomy and tubal ligation. Santow (1991) demonstrates the rapid increase in the use of the contraceptive pill from its introduction in 1961 through to 1986. Her research also describes the very low uptake of the intrauterine device (IUD). Despite the IUD being the most widely used reversible method in the world, there are considerable regional differences in its use, with much higher prevalence rates in developing countries (d’Arcangues 2007). Estimates from Australia show that few women use IUDs: less than 2 % of women of reproductive age (Gray and McDonald 2010; Yusuf and Siedlecky 2007). This level is similar to the USA (3.4 % in 2006–2008) (Mosher and Jones 2010) and Japan (2 % in 2000) (d’Arcangues 2007), while in the U.K. it is slightly higher: 8 % of women used an IUD or intrauterine system (IUS) in 2008–2009 (ONS 2009).

In fact, contraceptive uptake and method use varies considerably between (and within) countries. The reasons are numerous, and relate to the policy setting (Bateson et al. 2011), provider recommendations (Black et al. 2012; Gemzell-Danielsson et al. 2012; ONS 2009), individual knowledge (Bajos et al. 2003; Frost et al. 2008), and reproductive life stage (Gray and McDonald 2010; Lucke et al. 2009, 2011; Read et al. 2009).

This chapter starts by outlining the use of contraceptive methods across countries from which relatively comparable data is available. This is followed by a closer look at patterns of contraceptive use in Australia, and an investigation of how contraceptive use is related to fertility intentions.

7.2 Background

As noted by Sexual Health and Family Planning Australia (the national peak body for sexual health and family planning organisations in Australia), there ‘are no routinely collected data on contraceptive use in Australia that is (sic.) both reliable and complete’ (2013). From 1977 information on contraceptive use has been collected in the National Health Survey (NHS), but was last collected in this survey in 2001. There is also detailed information on contraceptive use in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health, a cohort study that started in 1996 with follow-up every 3 years. More recently, questions on contraceptive use have been asked in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. HILDA is a longitudinal panel study that follows individuals in households over time (see Technical Appendix). Data on contraceptive use were collected in 2005, 2008 and 2011, so while the HILDA sample is smaller than the NHS sample, it has the advantage of collecting information not only more recently, but also on the same individuals over time. It also covers all women of reproductive age.

Estimates based on 2008 data show that Australian women are most likely to use the contraceptive pill to prevent pregnancy (Gray and McDonald 2010). Around 30 % used oral contraceptives, including 8 % who used them in combination with condoms. Parr and Siedlecky (2007) note that this combination of methods is very common in Australia. Of women using a contraceptive method, 31 % used oral contraceptives, 21 % used condoms, 12 % used a combination of oral contraceptives and condoms, 14 % of women had a partner who had a vasectomy, and 10 % had tubal ligation. The remaining 12 % used IUDs, injectables, implants, and other methods including ‘traditional’ (non-medical) methods (Gray and McDonald 2010).

Like Yusuf and Siedlecky (2007) who used 2001 NHS data, Gray and McDonald (2010) found that oral contraceptive use was highest for women in their twenties, and condom use declined at each age group. Vasectomy and tubal ligation were also widely used, particularly from age 35.

Contraceptive use is not only related to age but is also closely related to fertility intentions or reproductive life course stage (Gray and McDonald 2010). Longer acting contraceptive methods tend to be used when people have completed their families (Gray and McDonald 2010), and women change their contraceptive use after birth, miscarriage and termination. Lucke et al. (2011) found that women increase their contraceptive use after a birth, decrease their use after a miscarriage, and change contraceptive method following a termination.

7.3 Data

As contraceptive method use is only collected in sample surveys in Australia, we use the HILDA survey to examine the prevalence of contraceptive method, and the factors associated with contraceptive method. The HILDA sample is broadly representative of the Australian population, and has the most recent data on contraceptive use. The following provides more information about the HILDA data used, and the data used for comparative purposes.

7.3.1 Australia

HILDA is used to examine the factors associated with contraceptive use and method. We use waves 5, 8 and 11 of the data, collected in 2005, 2008 and 2011. These waves contain a panel of questions on fertility that were asked as part of an international comparative survey, the Generations and Gender Programme (GGP) (see also Sect. 5.5). Information about the GGP is available at http://www.ggp-i.org/. The fertility module contains information about fertility histories, pregnancy, contraception and fertility intentions, which are used in this paper to understand patterns of contraceptive use.

We also consider a number of socio-demographic factors that have been found to be associated with contraceptive method use. As indicated previously, age is associated with the type of contraceptive method used (Yusuf and Siedlecky 2007; Gray and McDonald 2010), but age is also associated with life course stage, specifically reproductive life course stage (Gray and McDonald 2010). Age is not a perfect measure of whether people have children, how many children they have, or whether and when they intend to have more children. For this reason, the number of children, and the timing of fertility intentions are also included in the analysis. There is also evidence of differences by education (Richters et al. 2007), and partnership status, geographical location, and cultural background are also likely correlates (Gray and McDonald 2010). Here, we consider difference in use by city, regional or remote area, and by country of birth and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status as measures of cultural background.

7.3.2 Comparison Countries

The Generations and Gender data are used to provide an international comparison of contraceptive use. The countries for which contraceptive data are available are Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Georgia, Germany, Norway, Romania and Russia. We use Wave 1 of the GGP survey that was collected in 2005 for most countries, and use HILDA Wave 5 collected in 2005 for comparative purposes.

7.4 Method

7.4.1 Cross-Country Comparison

The GGP data are used to compare patterns of contraceptive use. First, women of reproductive age (18–44)Footnote 1 are classified as to whether they are potentially ‘at risk’ of pregnancy. The sample includes women who are in a heterosexual partnership. The categories are (1) potentially at risk of pregnancy; (2) pregnant; (3) cannot get pregnant (physical reasons); (4) cannot get pregnant (respondent is sterilized); and (5) cannot get pregnant (partner is sterilized). Australia is included in these results, and the countries included are age-standardized to Australia’s age distribution in 2005 for comparability.

Categories 4 (sterilization) and 5 (partner sterilization) are, in most cases, procedures that have been undertaken for contraceptive purposes. However, in many of the GGP countries female sterilization does not distinguish between hysterectomy – a procedure that is not usually for contraceptive purposes – and tubal ligation that is. One might assume that male sterilization is usually for the purpose of contraception, but not all countries collect data on its use. As we will show, vasectomy and tubal ligation are widely used in Australia, so in later analysis they are included as contraceptive methods.

We then look at the methods of contraception used for those who are potentially at risk of pregnancy (category 1 above). A percentage distribution of contraceptive method use is provided for each country, and this distribution includes the percentage of women who are not using any contraception. Australia is investigated separately, as described below.

7.4.2 Australia

The Australian contraception data cannot be directly compared to the GGP data. This is because the GGP asks respondents to provide the main method, and then asks what additional methods are used in later questions. In comparison, the questions in the HILDA survey ask whether the respondent uses each and every method. This means that respondents can use more than one method, and a percentage distribution of a ‘main method’ cannot reasonably be determined. However, we report the percentage using each method. Method use, for the three major methods,Footnote 2 is then compared for different sections of the Australian population, and we specifically investigate factors that have been found to be associated with contraceptive method.

7.5 Results

7.5.1 Contraceptive Use Across Countries

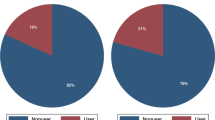

Typically, women who are not at risk of pregnancy are excluded from measures of contraceptive use. Figure 7.1 presents the categories of women who are not currently at risk of pregnancy alongside the majority who are at risk of pregnancy and therefore ‘at risk’ of using contraception. For those not at risk of pregnancy, Fig. 7.1 shows the reason that contraception is unnecessary (see also Appendix 7.1, Table 7.5).

Among non-users of contraception, Fig. 7.1 distinguishes between women who are pregnant, and those who are non-users for physical reasons or due to sterilization (of themselves or their partner). Note that in Norway respondents are not asked if they or their partners are sterilized, while in Estonia women are not asked if their partners are sterilized. For those countries the percentage that cannot get pregnant for physical reasons includes sterilization.

Australia stands out in the use of male methods of sterilization (vasectomy).Footnote 3 Around 15 % of partnered women state that their partners have been sterilized. In Austria, Georgia and Germany, around 5 % of women have experienced tubal ligation or hysterectomy, methods which are slightly more common in Australia (almost 10 %). The percentage of women who are pregnant varies between 2 % and 6.5 %.

The patterns of contraceptive method show large differences by country (Fig. 7.2, see also Appendix 7.1, Table 7.6). First, the percentage of women using contraception varies substantially. The lowest percentage using no contraception was in France (16 %), while the highest percentage using no contraception was in Georgia (44 %).

Women at risk of pregnancy: method of contraception by country (%) (see Appendix 7.1, Table 7.6). ‘Other’ includes diaphragm, cervical cap, foam, cream, jelly, suppository, emergency contraception and other. ‘PERSONA’ is a branded method that involves monitoring hormone levels through urine tests to provide information on which days a woman is at risk of becoming pregnant

Method use also varies by country. Withdrawal is virtually never reported in Austria, France, Germany and Norway, while a considerable percentage report its use in Bulgaria (28 %). The safe period method is used more in Georgia, Romania and Russia than in other countries. Condom use ranges between 10 % (Germany, Georgia and France) to around 26 % (Russia and Romania). The contraceptive pill is used by large percentages in Austria (36 %), and Germany and France (48 %). The IUD is most commonly used in Norway (28 %), and is also popular in other countries such as Russia (26 %), Estonia (23 %), France (21 %) and Austria (17 %).

7.5.2 Contraceptive Use in Australia

As previously discussed, contraceptive use in Australia has been dominated by oral contraception (the contraceptive pill). Data from Santow (1991) and Yusuf and Siedlecky (2007) clearly document these patterns in different age groups and over various cohorts of women from the 1970s onwards. The results of this analysis confirm that oral contraception remains the most commonly used method of Australian women (Table 7.1). As indicated, respondents to HILDA can provide multiple responses, although in most cases women only indicate one method. Table 7.1 provides the percentage of women using each contraceptive method for the years 2005, 2008 and 2011.

Table 7.1 includes two panels. The first includes all women aged 18–44 who are at risk of pregnancy; that is, they are not pregnant, and do not cite physical reasons for being unable to become pregnant (consistent with the aforementioned older studies, however, these data are not restricted to partnered women). The second panel includes only women who are current users of contraception.

The ‘all women at risk of pregnancy’ section of Table 7.1 is the most comparable to the cross-country GGP data, although it must be remembered that the HILDA survey allowed Australian women to nominate more than one contraceptive type. In 2005, which is the year of collection in most of the GGP countries, the levels of oral contraceptive use in Australia are similar to those in Austria and Norway, but are much lower than in France or Germany, while women’s reported use of the condom is considerably higher in Australia, but notably lower than in Russia and Romania. Further, the level of IUD use is lower than in all the countries included in the GGP, and in most cases, much lower. Although the rate of use of injectables and implants is somewhat higher than in the comparison countries, it is still a fairly low uptake at 5 %.

The results from 2005 to 2011 show some changes in the prevalence of contraceptive method type. Among women who are contraceptive users (Fig. 7.3), the dominance of oral contraceptives continues, and has increased, albeit slightly, between 2005 and 2011, with 48 % of contraceptive users indicating that they use oral contraceptives. In longer terms, this is up from about 40 % of contraceptive users in 1995 (ABS 1998). There have been declines in the percentages reporting tubal ligation (from 10 to 6 %) and partner vasectomy (14–13 %). The greatest increases are evident for women who are using IUDs (3–5 %) and implants (4–5 %). Allen (2012) notes that the ‘insertion of IUDs is returning to the domain of general practice’ (2012, p. 771), which may be associated with the reported increase in IUD use. It will be interesting to follow whether any further increase in IUD and implant use is associated with a further decline in tubal ligation.

7.5.3 Contraceptive Use by Characteristics of Partnered Women

Overall, there are socio-demographic differences in the type of contraception used (Table 7.2). These relate to age, partnership status, country of birth, parity and number of additional intended children. This section outlines the patterns that are evident in terms of contraceptive method use by women who are partnered.

Starting with the most commonly used contraceptive method, the results show that oral contraceptives are more likely to be used by partnered women who have no children (44 %) than those who have children. There is a decline in use over the age groups, with young adult women having the highest usage (almost 60 % of women aged 18–24). Those who intend to have two or more children (more than 45 %) are more likely to use oral contraceptives than those who intend no more children, or one more child, and those in a cohabiting relationship are more likely to use them than those who are married.

Condom use declines as the number of children ever born increases, and also at each age group. Condom are more likely to be used by partners of women who intend to have more children, and their use is very low among Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women.

There is also an age dimension to the use of injectables and implants for partnered women. Women aged 18–24 are most likely to be using one of these contraceptive methods (over 10 %). The other notable association is that women in de facto cohabiting relationships are more likely to be using this method.

Women are most likely to use an IUD if they have two children (almost 9 %), and the use increases at each age group. It is also more likely to be used by women who do not intend to have any more children than by women who intend another child. This is also the only method which married women are more likely to be using than cohabiting women.

We also examined the use of ‘traditional methods.’ Withdrawal and the safe period method show no particular differences by the background factors examined. These methods are often used for religious reasons, a factor not considered here because information on religion and religiosity was not consistently collected in the same waves as information on contraception.

These socio-demographic patterns are further examined using logistic regression. This provides insights into relationships between background factors and contraceptive method use, controlling for other factors in the model. Logistic regression is the most suitable method as it is possible that women were using more than one method: this means that a summative variable of main method used cannot be created. Hence, in these models, a woman can be a ‘user’ of both oral contraception and condoms (for example), and it is not possible to categorize her as one over the other.

The logistic regression results show that method use is associated with age in particular, but also reproductive life course stage (Tables 7.3 and 7.4). The results presented include models of oral contraceptive, condom, injectables/implants, and IUD usage. The model of use of withdrawal or safe period method is not shown, as there are no differences by background factors, with the exception of timing of fertility intentions. The results show that the only significant factor is whether a woman intends to have a child within 3 years or 4–5 years: these women are significantly more likely to be using withdrawal or the safe period method than women who intend to have no more children.

Looking first at the factors associated with contraceptive pill use (Table 7.3), the results show that women have a greater odds of using the contraceptive pill if they have no children or two children; presumably because effective contraception is most important to women who do not (yet) wish to have children and to those who may have completed their families (women with two children also have a higher odds of using the IUD). The contraceptive pill is also more likely to be used by young women aged 18–24. The odds of using oral contraception reduce at each age group from 25–29. Fertility intentions are also associated with using the contraceptive pill: women who plan to have a child in the next 3 or 4–5 years have a higher odds of using this contraceptive method.

The pattern for condom use is different, although it is also a method most likely to be used at younger ages. Partnered women are most likely to report using condoms at ages 18–19, 20–24 and 25–29. From age group 30–34 the use of condoms declines dramatically. Condom use is also associated with education level, with women who have at least a bachelor degree more likely to report use of condoms.

Injectables and implants are related to the number of children ever born (Table 7.4). Women who do not have children have significantly lower odds of using injectables compared with women who have two children. Women who have two children have odds 2.8 times higher of using an injectable or implant than women who have no children. As with the contraceptive pill, there is a decline in the use of injectables and implants over the age groups. Women aged 35+ are significantly less likely to be using one of these methods than women aged 20–24 and women who are married are less likely to be using these methods than those in cohabiting relationships.

Finally, IUD use shows very little relationship to any of the explanatory factors except the number of children born. This method tends not to be used by women who haven't had children. The odds are highest for women with two children, probably reflecting the strong two-child norm in Australia (see Chap. 9). Although not statistically significant, women who intend to have a child in the next three years have very low odds of use.

7.6 Conclusion

Partnered women in Australia predominantly use the oral contraceptive pill. The rate of use in Australia is similar in Austria and Germany, but is otherwise considerably higher than in the comparison countries considered. Two other methods that are used widely in Australia compared to other countries are vasectomy and tubal ligation.

However, there have been notable changes over recent years in the use of different contraceptive methods. Contraceptive pill uptake continues to increase, up from 40 % in 1995 to over 48 % of users in 2011. IUD and implant use has increased in recent years, but there has been decreased use of tubal ligation, vasectomy and injectables.

The use of different methods is associated with age and reproductive life course stage. While there are clear trends in use at different age groups, the number of children born and fertility intentions are both important considerations when decisions are made about contraceptive method. Women are more likely to use the pill or implants/injectable when they have no children, while IUD use is associated with having had two or more children. It appears that this is not a method chosen by, or perhaps recommended to, young or nulliparous women. Allen (2012) suggests that the introduction of a ‘mini’ version of an IUD may increase usage by these women.

Despite the increase in the use of IUDs by Australian women, their use is still substantially lower than in some European countries like France and Norway. It is interesting that although Australia has had a similar level of fertility to France, the USA, and the Scandinavian countries, the means by which these fertility levels are achieved are quite different. While US data is not strictly comparable with the GGP data analysed in this chapter, the US has comparatively high levels of partner sterilization (vasectomy is used by around 11 %) and condom use (25 %), similar levels of individual sterilization (around 6 %), and lower levels of contraceptive pill use (25 %) (ONS 2009). Among the countries included in this analysis, France had the highest use of oral contraceptives, while Norway had high levels of IUD use.

Condom use, which is relatively high in Australia, showed interesting differences by education level: women with higher levels of education were more likely to state that they were using this as a method of contraception. This method requires negotiation between both partners in a couple, and so perhaps condoms are better suited to women with higher levels of education.

Most striking is that the contraceptive methods used today are dominated by modern medical methods that are almost entirely controlled by women. Methods involving men’s cooperation have declined in use, particularly over the last 40 years or so, with very low levels of withdrawal and declines in condom use. We will watch with interest how medical technology and individual uptake progresses over the coming years.

Notes

- 1.

While most countries asked about contraceptive used up to age 49, for comparability the age range 18–44 is used as Austria does not ask women aged over 44 about contraceptive method.

- 2.

Multivariate analysis of the use of vasectomy and tubal ligation is not included because respondents are not asked about fertility intentions. One can assume that these methods have been used because the respondent does not intend to have a child in the future.

- 3.

Note that as vasectomy and tubal ligation are widely used in Australia as contraceptive methods, they are included as contraceptive methods in the analysis of factors associated with contraceptive type for Australia. It is not possible to include vasectomy and tubal ligation as contraceptives in the comparative analysis because there is such a wide difference in the information collected between countries.

References

ABS. (1998). Australian Social Trends 1998 (Cat. no. 4102.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Allen, K. (2012). Contraception: Common issues and practical suggestions. Australian Family Physician, 41(10), 770–772.

Bajos, N., Leridon, H., Goulard, H., Oustry, P., Job-Spira, N., & The COCON Group. (2003). Contraception: From accessibility to efficiency. Human Reproduction, 18(5), 994–999.

Bateson, D., Harvey, C., Williams, J., & Black, K. (2011). Intrauterine contraception: Why are so few Australian women using this effective method? Medical Journal of Australia, 194(6), 324.

Black, K., Lotke, P., Buhling, K., & Zite, N. (2012). A review of barriers and myths preventing the more widespread use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 17, 340–357.

d’Arcangues, C. (2007). Worldwide use of intrauterine devices for contraception. Contraception, 75, S2–S7.

Frost, J. J., Darroch, J. E., & Remez, L. (2008). Improving contraceptive use in the United States (In Brief, 1). New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Gemzell-Danielsson, K., Cho, S., Inki, P., Mansour, D., Reid, R., & Bahamondes, L. (2012). Use of contraceptive methods and contraceptive recommendations among health care providers actively involved in contraceptive counselling – Results of an international survey in 10 countries. Contraception, 86, 631–638.

Gray, E., & McDonald, P. (2010). Using a reproductive life course approach to understand contraceptive method use in Australia. Journal of Biosocial Science, 42(1), 43–57.

Lucke, J., Watson, M., & Herbert, D. (2009). Changing patterns of contraceptive use in Australian women. Contraception, 80, 533–539.

Lucke, J., Herbert, D., Watson, M., & Dobson, A. (2011). Contraceptive changes after reproductive events among Australian women born in 1973 to 1978: A longitudinal study from 1996 to 2009. Women’s Health Issues, 21(6), 438–443.

Mosher, W. D., Jones, J. (2010). Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Statistics, Series 23(29).

Office of National Statistics. (2009). Contraception and sexual heath, 2008/09. Opinions survey report 41. London.

Parr, N., & Siedlecky, S. (2007). Use of ‘dual protection’ and other combinations of contraceptive methods in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31(6), 567–570.

Read, C., Bateson, D., Weisberg, E., & Estoesta, J. (2009). Contraception and pregnancy then and now: Examining the experiences of a cohort of mid-age Australian women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 49, 429–433.

Richters, J., Grulich, A., de Visser, R., Smith, A., & Rissel, C. (2007). Contraceptive practices among a representative sample of women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 210–216.

Santow, G. (1991). Trends in contraception and sterilization in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 31(3), 201–208.

Sexual Health and Family Planning Australia. (2013). Research and data gaps. http://www.shfpa.org.au/research-and-data-gaps. Accessed 17 May 2014.

Yusuf, F., & Siedlecky, S. (2007). Patterns of contraceptive use in Australia: Analysis of the 2001 National Health Survey. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39, 735–744.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix 7.1

Appendix 7.1

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gray, E., Arunachalam, D. (2015). Patterns of Contraceptive Use. In: Heard, G., Arunachalam, D. (eds) Family Formation in 21st Century Australia. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9279-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9279-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9278-3

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9279-0

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)