Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of recent trends in divorce and relationship dissolution in Australian society. It commences by describing historical and contemporary trends in marriage dissolution using Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data. These data offer little insight into the dissolution of cohabiting relationships. To fill this gap we use unit record data from the first 10 waves of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey to compare and contrast the stability of marital compared to cohabiting relationships since 1995. Next we examine the consequences of marital and cohabiting relationship dissolution for income and health outcomes for men and women. We conclude with a brief discussion of the extent to which unstable marriages have been replaced by cohabitation.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

5.1 Introduction

As in most other western developed countries, marriage breakdown has increased in Australia, particularly since the end of World War 2. While the increase in the rate of divorce in Australia has slowed since the 1980s and may have even stabilized and started to decline, the nature and characteristics of divorcing couples continue to change. It is very likely that these changes in divorce trends are underpinned at least in part by the rise of unmarried, or de facto, cohabitation (henceforth cohabitation) as an alternative or ‘stepping stone’ to marriage. Cohabiting relationships are less stable than marital relationships, but we know little about the stability of cohabiting relationships from official statistics. Thus, official statistics underestimate the true extent of relationship dissolution in the Australian population. In this chapter we document historical trends, explore changes in the nature and characteristics of divorce in Australia and examine differences in the dissolution of cohabiting and marital relationships using survey data.

5.2 Historical Trends

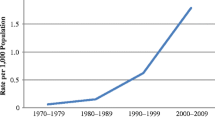

Rates of divorce in Australia have increased considerably over the last century. Figure 5.1 reports the crude divorce rateFootnote 1 in Australia since 1901.Footnote 2 At the turn of the twentieth century divorce was virtually non-existent in Australia, with only 398 divorces granted in 1901 and a crude divorce rate of less than 0.1 (ABS 1971). The rate then increased gradually from the mid-1960s until 1975.

In 1976 no-fault divorce was introduced with the implementation of the 1975 Family Law Act and the crude divorce rate spiked to 4.6 per thousand head of population aged over 15 (Fig. 5.1). The new Family Law Act 1975 sought to establish a law based upon two pillars: ‘the support for marriage and family; and the right of a party to leave a marriage upon its irretrievable breakdown, the latter being evidenced by 12 months separation of the parties’ (Australian Parliament House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs 1998: 95). The 14 grounds of divorce were replaced by one – irretrievable breakdown. Within a few years the crude divorce rate dropped to around 2.6 per thousand head of population over the age of 15 and has oscillated between 2.5 and 3.0 since the late 1970s. The introduction of the 1975 Family Law Act, and with it no-fault divorce, dramatically and permanently changed the rate of divorce in Australia.

Some have argued that the easy access to divorce provided by the Family Law Act was a major cause of the substantial increase in divorce in Australia from the mid-1970s. The data indicate, however, that the rise in the crude divorce rate following the introduction of the Family Law Act was relatively short-term. Within five years of the Act being introduced crude divorce rates had settled to a rate that reflected linear trends established in the mid-1960s (Ozdowski and Hattie 1981). It is likely that the spike in divorce was primarily a response to pent-up demand from couples that had separated but not divorced in the late 1960s and early 1970s. There is some survey evidence for this. Burns (1980a, b) conducted a study on separation and divorce in late 1975, prior to the introduction of no-fault divorce, and found that some separated respondents were waiting for the introduction of the Family Law Act to divorce legally. Despite minor yearly fluctuations the steady increase in the crude divorce rate evident prior to 1976 has ceased and there has been little change since the early 1980s. Since the year 2000, the trend suggests a decline in divorce (see Fig. 5.1); in 2008 divorce rates were at their lowest in 20 years (ABS 2009).

5.3 Continuity and Change Since No-Fault Divorce

Despite the plateau and decline in the crude divorce rate, divorce continues to be a pervasive feature of Australian social life. Thirty-two percent of current marriages are expected to end in divorce and this is predicted to increase to 45 % over the next few decades, with younger marriage cohorts more likely to divorce (Carmichael et al. 1996). Further, there is widespread government and community concern about divorce and its consequences as evidenced by recent government policy and legislative reforms (Australian Parliament House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs 1998; Kaspiew et al. 2009).

Ongoing changes in divorce in Australia are more clearly revealed if we use measures other than the crude divorce rate. The crude divorce rate indicates the rate of breakdown in the total Australian population aged over 15, including those who are married and unmarried. Given that rates of marriage have also declined since the late 1970s, the crude rate may be under-estimating marriage breakdown because its denominator is not restricted to the married population (de Vaus 2004). An alternative indicator is a divorce rate which uses the married population as the denominator. Figure 5.2 shows the divorce rate of the married population in Australia between 1981 and 2001.Footnote 3

Divorce rate, Australia 1981–2001 (ABS 2005a)

Compared to the crude divorce rate, this divorce rate is much higher. While the divorce rate shows a very similar pattern to the crude divorce rate, the peaks and troughs are more pronounced. The rate of divorce has varied from a low of 10.6 per 1,000 married men or women in 1987 to a high of 13.1 in 2001. Data from the 2006 Census indicate that this figure had dropped to 12.0, and the 2011 Census data indicate that it had further declined to 11.6 (ABS 2012c). These declines are consistent with the general decline in the crude divorce rate since 2000.

Other characteristics of divorce in Australia such as age at divorce, average time to divorce and number of dependent children involved in divorce have also changed since the 1980s. These changes reflect broader social and demographic changes in relationship formation and fertility timing in Australia over the last three decades. Figure 5.3 illustrates that since the introduction of the Family Law Act in 1976 the median age at divorce has increased from 36.1 in 1977 to 44.5 in 2011 for men and from 33.0 to 41.7 over the same period for women.

It is likely that the median age at divorce is increasing due to two factors. First, people are marrying at older ages. In 1977 the median age at first marriage was 23.8 years for men and by 2011 this had increased to 29.7 years. Similarly for women the median age at first marriage increased from 21.4 years in 1977 to 28.0 years in 2011 (ABS 2005d, 2012c).Footnote 4 Second, the median duration of marriage to separation and divorce has increased. Figure 5.4 shows that the main increase occurred between 1997 and 2006, when the median duration of marriage to separation increased from 7.7 to 9.9 years, and of marriage to divorce from 11.1 to 12.5 years. There was also an increase in the time between separation and divorce, from 2.7 years in 1981 to 3.5 years in 2011, with most of that increase occurring during the 1990s.

The proportion of divorces involving children under the age of 18 has also changed over time. Figure 5.5 illustrates a decline in the proportion of divorces involving dependent children from 63 % in 1977 to around 50 % by 2003, and this proportion has dropped below 50 % since 2007 (ABS 2012b). This reduction in the proportion of divorces with dependent children is due in part to delayed child bearing (see Chap. 9).Footnote 5 Even though the proportion of divorces involving children has dropped since the early 1980s, the actual number of children whose parents divorce each year has remained fairly constant at around 50,000 children (ABS 2001, 2012b).

In summary, despite a plateau and recent decline in the divorce rate, the nature and composition of the divorcing population has continued to change with increases in age at divorce and time to divorce and a decline in the proportion of divorces involving children. When considering these trends in marriage breakdown the limitations of official statistics also need to be taken into consideration.

First, official divorce statistics tend to underrepresent marriage breakdown at any given point because many marriages end in permanent separation and never proceed to divorce or do not proceed to divorce for several years; the median time from separation to divorce was 3.5 years in 2011 (ABS 2012b). In these circumstances marriage breakdown is not officially recorded until divorce is awarded (ABS 1999, 2000).Footnote 6

In Table 5.1, we present the results of marital history information on those who had separated or divorced from their first marriage in wave 1 of HILDA (2001).Footnote 7 We find that approximately 18 % of those who had separated from their marriage had not gone on to divorce by the time of survey. The average duration of separation of those people who had separated but not legally divorced was 5.7 years. This average is 2 years longer than that reported by official divorce statistics in 2011. This is because the ABS divorce statistics are recorded when a couple divorces. While the majority of separated people had only recently separated in the HILDA sample (63 % of them having separated less than 2 years before the survey), about 20 % of the separated people had been separated for 10 years or more without divorcing.

The second major limitation of official divorce statistics is that they significantly under-represent the true extent of relationship dissolution in Australia, because they do not take into account the increasing number of cohabiting relationships. In the remainder of this chapter we examine differences in the dissolution of cohabiting and marital relationships.

5.4 Marriage and Cohabiting Relationship Dissolution: Evidence from HILDA

Arguably, many of the changes in the timing of divorce and composition of the divorcing population since the 1980s are underpinned by changes in family and relationship formation and in particular the increasing number of couples who are in cohabiting relationships (see Chap. 2). While the rise of cohabitation is contributing to changing patterns of divorce, the contribution of cohabitation to overall rates of relationship dissolution is not captured by official divorce statistics. Previous Australian and overseas research has indicated that cohabiting relationships tend to be less stable than marital relationships (Qu et al. 2009), but we know little about the pattern and nature of the differences in dissolution between the two types of relationships. To better capture the extent of relationship dissolution in Australia from both cohabiting and marital relationships, we need survey data.

The majority of previous research on cohabitation and relationship dissolution has concentrated on the dissolution of marriage after a period of cohabitation. Most studies find that a period of cohabitation prior to marriage increases the risk of subsequent divorce (Bennett et al. 1988; Teachman and Polonko 1990; Axinn and Thornton 1992; DeMaris and Rao 1992; Bracher et al. 1993; Hall and Zhao 1995; Lillard et al. 1995; Berrington and Diamond 2000; Dush et al. 2003; Hewitt et al. 2005). Far fewer studies have investigated the dissolution of cohabiting relationships that do not proceed to marriage (see Schoen 1992; Thompson and Collela 1992 for notable exceptions).

In this chapter we are not only interested in what happens after marriage (preceded by cohabitation or not), but also in what happens with cohabiting relationships that do not proceed to marriage. There are three potential pathways cohabiting relationships can follow: couples can continue to cohabit, become legally married or separate (Qu et al. 2009). To investigate relationship dissolution among cohabiting and marital relationships, we differentiate between three mutually exclusive relationship groups, those who are: (1) married without prior cohabitation, (2) cohabiting only, and (3) married after a period of cohabitation. So that we are not comparing cohabiting relationships with long-term marriages we restrict our examination to first marriages only and to relationships formed since 1995. Our sample is respondents in HILDA Waves 1–10 (2001–2010).

In Table 5.2 we show the overall proportion of respondents in the abovementioned three relationship groups, for relationships commencing between 1995 and 2010. The final column in the table provides the total proportion of each relationship type observed over that time. The most common relationships were cohabitating only relationships (42 %), followed by cohabitations that resulted in marriage (38 %), with the fewest number of people marrying directly (19 %). The small proportion of those marrying directly is consistent with ABS data indicating that the proportion of people cohabitating prior to marriage has increased from 67.2 % in the late 1990s to 78.2 % in 2011 (ABS 2007, 2012c). The middle column of the table indicates that the majority (69 %) of the relationships that ended in HILDA between 1995 and 2010 were cohabiting only relationships.

While this information provides us with a summary of relationship dissolution across these relationship groups, there are a number of limitations to this approach when examining relationship dissolution. Relationship dissolution is a time-dependent event (Heaton et al. 1985; Heaton 1991; Heaton and Call 1995), where the risk of dissolution may increase or decrease over the duration of the relationship. To better understand the nature and extent of differences in the time dependency of relationship dissolution for these relationship types, we use retrospective and prospective relationship information from the first 10 waves of HILDA.

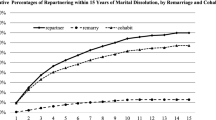

We examine relationship survival and the hazards of dissolution over the first 15 years of the relationship, restricting our analyses to relationships formed after 1995. First we examine the survival function, which tells us the proportion of respondents surviving relationship breakdown at each year. Figure 5.6 plots the survival function for separation from first marriages, cohabitating relationships and first marriages preceded by cohabitation in the sample. The 15-year survival of first marriages formed since 1995 in our sample is 92.6 %, and the first 5 years of marriage for this group are very stable. This differs from previously published Australian research on marriage dissolution (see Hewitt et al. 2005: 173), which indicated that approximately 82.8 % of marriages survived the first 15 years and that many marriages ended within the first 5 years. However, the previous study included marriages that had formed in the 1930s and 1940s when divorce and cohabitation were rare, as well as marriages that were formed in the 1960s and 1970s when cohabitation was relatively rare, but divorce was increasing. Thus the earlier figures represented an average over all marriages irrespective of the year of marriage. The results here suggest that for more recent marriages formed since 1995, early marriage is relatively stable.

Fifteen-year survival of de facto cohabitations and first marriages formed after 1995 (HILDA 2001–2010, see Appendix 5.1)

The 15-year survival of marriages preceded by cohabitation is marginally higher at 93.1 % than of those not preceded by cohabitation. Finally, Fig. 5.6 shows that cohabiting relationships that have not proceeded to marriage have much lower survival rates at all relationship durations, with very small numbers of cohabiting relationships reaching 15 years duration (numbers not shown) and only 64.7 % of these relationships surviving at 15 years duration.

An alternative way of looking at the timing of relationship dissolution is the hazard rate. The hazard rate represents the likelihood of experiencing relationship dissolution given that the relationship did not end in the previous year (Yamaguchi 1991: 9). In other words the hazard indicates the proportion of relationships that ended in separation for each time interval, given that the respondent was still in their relationship at the previous time interval. In Fig. 5.7, the hazards of relationship dissolution for each group are presented. The graph shows that the hazards of relationship dissolution are similar for those who are married with or without a period of cohabitation and are relatively low. There is an overall trend of increasing hazard of dissolution over time, with marriages preceded by cohabitation having a slightly elevated risk of dissolution over the 12 years of relationship duration. However, additional analysis indicates that there were no significant differences in the hazards of relationship dissolution for direct marriages and marriages preceded by cohabitation. This finding is consistent with recent research that suggests the increased risk of divorce for those who cohabited before marriage has diminished or disappeared for younger cohorts (Klijzing 1992; Schoen 1992; de Vaus et al. 2005; Hewitt and de Vaus 2009).

Hazards of relationship dissolution for cohabiting and first marriages formed after 1995, HILDA 2001–2010 (see Appendix 5.1)

Figure 5.7 also shows that cohabiting relationships that do not proceed to marriage have a higher likelihood of dissolution at all relationship durations. The U-shaped pattern of likelihood of dissolution from cohabitations is very different from the gradual increase for those who married (either with or without a period of cohabitation). The U-shape distribution indicates the likelihood of dissolution in the first couple of years of a cohabiting relationship is very high, then stabilises once the relationship reaches 3 years in duration and increases quite dramatically again after 10 years. It should be noted that the number of cohabiting relationships at 10 years was relatively small and therefore the hazard estimates are less reliable. Therefore these results for cohabitations of longer durations should be treated with some caution. We restrict Fig. 5.7 to 12 years’ relationship duration.

These patterns of relationship dissolution for marital and cohabiting relationships formed since 1995 in HILDA are interesting for their departure from patterns recorded by previous generations and the ways in which they reflect more recent trends in relationship formation. Many couples use cohabitation as a ‘trial’ marriage (Seltzer 2000; Manning and Smock 2002; Qu et al. 2009). It appears that many of the marriages that might once have ended in the first few years of marriage may have been replaced by cohabiting relationships. This has resulted in a lower risk of divorce early in marriage for more recent marriage cohorts than in previous marriage cohorts. As in previous generations, Australians continue to form relationships that are relatively unstable in their early years, but in more recent generations those relationships are less likely to be legalised with marriage.

5.5 Why Is Cohabitation Less Stable?

With the increase in cohabitation as either a prelude or alternative to marriage, a large and growing body of work comparing and contrasting cohabitation and marriage has emerged. Understanding differences between couples that choose to cohabit or marry is important for explaining why cohabiting relationships tend to be less stable. Arguably, the most prominent recent explanation for differences between cohabiting and married couples is commitment theory. According to commitment theory the motivation for cohabiting rather than marriage is based on a lack of personal dedication to a partner and constraint commitment (Stanley et al. 2004).

Personal dedication refers to interpersonal commitment associated with a strong desire for the relationship to last into the future (Rhoades et al. 2011). Some research indicates that cohabiters as a group tend to value individual freedom more than their married counterparts (Axinn and Thornton 1992; Thompson and Collela 1992). Other research finds that cohabiters tend to have lower levels of relationship commitment and fewer moral constraints to stay in their relationship than married couples (Nock 1995; Brown and Booth 1996). These differences suggest that cohabiters have lower levels of interpersonal commitment to their partner and to being in a relationship than married people.

Constraint commitment refers to the costs of ending or leaving a relationship including financial constraints (i.e. access to income, home ownership), social pressure and concerns for children (Stanley et al. 2006: 503). Overall, cohabiting relationships have lower levels of constraint commitment, in that partners are more likely to keep their money separate (Vogler et al. 2006), less likely to own a house together (Mulder and Wagner 2001; Baxter and McDonald 2004) and less likely to have children in the relationship (ABS 2012a); although it should be noted that a significant number of children are now being born to couples who are not married.

Interestingly, this argument also highlights the fact that the transition from cohabitation to marriage may not necessarily indicate a greater level of interpersonal commitment. Rather, once involved in a longer term cohabiting relationship, the costs of leaving may be a more important determinant of the stability of the relationship or the transition to marriage than personal dedication to one’s partner (Stanley et al. 2006). Some long-term cohabiters with high levels of constraint commitment, such as children or co-ownership of a house, resemble married couples. For example, Willets (2006) finds that long term cohabiting relationships with high levels of constraint commitment have similar levels of relationship quality to marital relationships. However, long-term cohabiting relationships of a highly committed nature are still relatively rare (Kiernan 2002; Seltzer 2004; Qu et al. 2009).

This research suggests that, overall, cohabiting couples have lower levels of dedication to the relationship with their partner and fewer structural constraints to ending the relationship when compared to married couples. These factors are likely to strongly influence decisions that partners make about whether to remain in the relationship or to end the relationship. Using the Generations and Gender Survey (see Sect. 7.3.1) to compare and contrast cohabiting and married couples across eight European countries (Bulgaria, France, Germany, Hungary, Norway, Romania, Russia, and The Netherlands), Wiik et al. (2012) find that cohabiters are more likely to have plans to break-up than married couples.

5.6 The Consequences of Relationship Dissolution

Of primary concern to researchers and policy makers are the consequences of relationship dissolution for individuals, families and children. The growth in marriage breakdown is significant because there are substantial short and medium term, social, psychological and economic costs for spouses and children (Amato 2000), as well as very significant costs to the national economy (Australian Parliament House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs 1998). Marital dissolution is not only an emotionally stressful event for individuals, but results in changes in many areas of life including employment, household income, and household composition (Wood et al. 2007). Despite the dramatic rise in cohabitation, and the instability of cohabiting unions, few studies have investigated the consequences of relationship dissolution for those in cohabiting compared to marital unions.

While cohabitation seems to offer some similar advantages to marriage, the important differences outlined in the previous section suggest that when relationships end we might expect that separating from cohabitation may have less impact on people’s lives than separating from marriage. Two outcomes that have been investigated are the consequences of relationship dissolution for income and health and wellbeing.

5.6.1 Income

Previous research in Australia (Smyth and Weston 2000), the United States (Bianchi et al. 1999) and Europe (Poortman 2002; Uunk 2004; Aassve et al. 2007; Andreß and Bröckel 2007) finds that men do better financially after separation than women. Typically after marital separation men’s household income remains relatively stable and women’s decreases (Andreß and Bröckel 2007). These differences are likely due to gender differences in changes in household composition combined with gender differences in earnings. For men, the average number of people in their household diminishes after relationship dissolution as they are less likely to have primary responsibility for the care of children, but their household income does not decline dramatically as men typically contribute the majority share to household income before the relationship ends (Bianchi et al. 1999; Smyth and Weston 2000). In contrast, women’s household size decreases less after relationship dissolution because they are more likely to have greater care responsibilities for children, but their household income decreases more dramatically as they tend to contribute less to household income. We know little about what happens when cohabiting relationships break down.

To compare and contrast the consequences of relationship dissolution from cohabiting and marital relationships we use a measure of household income that includes any tax transfers, government benefits, private transfers (such as the payment of child support) and income from salary, wages, and business. We use this measure as it captures the total income available in the household for consumption or savings. We also equivalise our income measure because the financial needs of households change with each additional member, and equivalised income better captures people’s actual standard of living as it takes household composition into account. Due to large gender variations in the household composition of spouses after separation the most appropriate measure of household income is equivalised household income. In the HILDA Waves 1–10 sample we found that women who separated from marriage had the largest average household size after separation (2.4 persons) and cohabiting men who separated had the smallest (1.01 persons) while women who separated from cohabiting relationships (1.7 persons) and men who separated from marriage (1.5 persons) were in between.

In Fig. 5.8, we show the predicted equivalised household income for men and women after separation from marriage and cohabitation. We plot equivalised household income at three time points: in the year prior to relationship dissolution; in the year of dissolution and in the year after dissolution. In the left panel we present the predicted equivalised income for men. The graph shows that men’s equivalised household income increased after separation. There were no differences in the household income of men who were married compared to men who were cohabiting before or after relationship dissolution. The picture for women is quite different. Not surprisingly women in cohabiting and marital relationships have similar equivalised household incomes to men. After relationship dissolution, however, cohabiting women’s equivalised household income increased in a similar pattern to that for men. In contrast, equivalised household income for women who separated from marital relationships remained stable and was not significantly different from equivalised household income when they were married.

Equivalised annual household income after separation from cohabitation and marriage, by gender (HILDA 2001–2010) (Models control for union duration, age, employment status and highest level of education. See Appendix for more information on modelling approach used (Hewitt and Poortman 2010))

The main finding that cohabiting women have a stronger financial position after separation than married women is consistent with previous research in two main ways. First, cohabiting women tend to contribute a higher share of household income during the relationship than married women (Kalmijn et al. 2007). Second, couples in cohabiting relationships are less likely to have children than couples in marital relationships (Hewitt et al. 2010), and therefore cohabiting women are less likely to have dependent children to care for after separation. Even though a significant proportion of children are currently born in cohabiting relationships, the majority is born within marital relationships. Together these two factors likely contribute to the stronger financial position of cohabiting women than married women after separation.

5.6.2 Health

It is well documented that intimate relationships are important to health (Carr and Springer 2010). A large number of studies spanning decades show that, compared to being unmarried, being married is associated with better physical and mental health and well being (Gove and Shin 1989; Wade and Pevalin 2004; Williams and Umberson 2004; Willitts et al. 2004; Strohschein et al. 2005; Bennett 2006; Zhang and Hayward 2006) and lower rates of mortality (Grant et al. 1995; Nagato et al. 2003; Brockman and Klein 2004; Dupre et al. 2009). A handful of studies have compared the health profiles of people in marital and cohabiting relationships, and the findings of these studies are mixed. In general no differences are found in the physical and mental health of cohabiting versus married people (Horwitz and White 1998; Wu et al. 2003); if differences are found cohabiters tend to have poorer health than married couples (Brown 2000).

People who are separated, divorced or widowed have worse health than their partnered or never-married counterparts (Bierman et al. 2006; Wood et al. 2007), which suggests that marital loss may be particularly consequential for health. Far fewer studies have investigated what happens to health when cohabiting relationships end. While cohabitation seems to offer some similar health advantages to marriage, there are some important differences in the experiences and conduct of cohabiting relationships that may indicate differences in the health consequences of ending such relationships; although the scant evidence to date suggests that there are no differences in the health consequences of separation for married and cohabiting couples (Wu et al. 2003).

We examine the consequences of relationship dissolution from cohabiting and marital relationships for physical and mental health. Figure 5.9 shows the physical health consequences of separation for men and women from marital and cohabiting relationships. For men, there were no physical health differences by union type or stability, although the graph suggests a decline in health for cohabiting men leading up to separation, followed by a return to previous health levels by one year after separation. For women, those who separate from cohabiting or marital relationships have a small improvement in their physical health (although physical health scores are similar to those recorded before the relationship ended).

Physical health (SF-36) after separation from cohabitation and marriage, by gender (HILDA 2001–2010) (Models control for relationship duration, age, number of children under 18 in the household 50 % or more of the time, household income, employment status, highest level of education and health status at the previous wave. See Appendix 5.1 for more information on modelling approach used (Hewitt et al. 2012))

In Fig. 5.10, we show the mental health consequences of relationship dissolution for men and women in cohabitation and marital relationships. These graphs show similar patterns for men and women. First, those who experienced separation from a relationship had poorer mental health before and after the transition. This is consistent with previous research which suggests that prior to a relationship ending men and women experience low levels of relationship quality which negatively affect mental health (Kalmijn and Monden 2006). Second, the results indicate that the mental health consequences of separation from marriage are significantly worse than for separation from cohabitation. Finally, we see that within a year or two after separation, mental health has recovered to levels similar to those recorded prior to separation, and for women are slightly higher than prior to separation. Thus the consequences of relationship dissolution for mental health also appear to be short-lived.

Mental health (SF-36) after separation from cohabitation and marriage, by gender (HILDA 2001–2010) (Models control for relationship duration, age, number of children under 18 in the household 50 % or more of the time, household income, employment status, highest level of education and health status at the previous wave. See Appendix 5.1 for more information on modelling approach used (Hewitt et al. 2012))

These results indicate that relationship dissolution has a stronger and more negative association with mental health, though not long-lasting, than for physical health. There are also clear negative mental health implications for those separating from marriage compared to those separating from cohabiting relationships, and these findings are consistent for men and women. There are, however, some important gender differences for household income. For men, equivalised household income improves and there are no differences in the consequences of relationship dissolution for men who are cohabiting or married. In contrast, married women have a much lower equivalised household income after separation than cohabiting women after separation. On balance, our results suggest that separation from cohabitation has far less severe consequences for finances and health than separation from marriage.

5.7 Discussion

The goal of this chapter was to illustrate continuity and change in the nature of relationship dissolution in Australia and to provide insights into recent trends and outcomes. Over the last century in Australia divorce has gone from being virtually non-existent to becoming a common feature of family life by the mid-1970s (Hewitt et al. 2005). While this sparked a moral panic about a crisis in ‘the family’ late last century, there is little evidence that such a crisis has occurred. Since the early 1980s the rate of divorce has slowed, stabilised and from the year 2000 is showing a slight decline. In addition, the nature and characteristics of divorcing couples continue to change, with increases in the median age at divorce and time to divorce and decreases in the proportion of divorces involving children. These trends are consistent with the stabilisation of the overall rates of divorce and suggest that fewer children are being affected by divorce now and in the future. However, marriage has also transformed and one factor that may partially explain these trends in the legal dissolution of marital relationships is the increasing number of cohabiting relationships that are not captured in official statistics. This suggests that some unstable marriages have been replaced by cohabitations.

Using data from the HILDA survey we compared and contrasted the stability of married and cohabiting relationships. Consistent with broader trends shown by official statistics, which indicate that marriage has stabilised, we find that marriage, and in particular early marriage, is relatively stable. In contrast, our examination of cohabiting relationships provides good evidence that Australians are not necessarily experiencing relationship dissolution at lower rates than in the past. In fact, if anything, they are possibly experiencing higher rates of overall relationship dissolution, but in cohabiting relationships rather than marriage.

It is well documented that on average the nature and circumstances of cohabiting relationships differ from those of marriages (Stanley et al. 2004). These differences, such as lower average levels of emotional as well as structural commitment amongst cohabiters, provide strong insights into why cohabiting relationships are less stable. These differences also suggest that in the case of relationship dissolution the consequences for cohabiters may be less severe. However, few studies have tested this idea. In this chapter we contrasted the financial and health consequences of relationship dissolution for cohabiters compared to those who are married. We find that while relationship dissolution does tend to have a negative impact on financial and mental well being, the consequences are stronger for married people.

These results on the consequences of dissolution for cohabiters and married respondents in Australia are not entirely consistent with previous research in the field. We find significant mental health differences for cohabiting and married respondents who experience relationship dissolution, but a Canadian study found no significant differences in the mental health consequences of relationship dissolution for married or cohabiting respondents (Wu and Hart 2002). We also find that married women fare significantly worse financially than cohabiting women after separation, even though the financial position of married women after separation relative to their position prior to separation is not significantly worse. Previous Australian research suggests that this is largely due to the flow of government transfers into separated women’s households (Hewitt and Poortman 2010). However, a US study using the Longitudinal Survey of Youth concludes that women whose cohabiting relationships end have similar financial standing as previously married women (Avellar and Smock 2005).

The overall picture of relationship dissolution in the Australian context, provided by this chapter, is relatively positive. Officially, the trends suggest more stable and potentially lower divorce rates in the future. Even though Australians are experiencing high rates of relationship dissolution from cohabiting unions, the evidence presented here suggests that the emotional, social and financial effects of separation from cohabiting relationships are less severe than they are from marriages. Most couples whose relationships end are able to progress with their lives and those with children often renegotiate their post-separation relationship in positive ways (Funder 1996; Smart and Neale 1999; Smart 2000). Nevertheless in the short term there are major social, emotional and financial implications for both men and women experiencing relationship dissolution from cohabitation and marriage (Amato 2000). It is thus important to maintain social and financial supports for Australian couples who have experienced relationship dissolution, whether from cohabitation or marriage, and to continue to monitor trends and outcomes given the rapid rate of change in patterns of family formation and dissolution.

Notes

- 1.

The crude divorce rate is the number of divorces granted each year per 1,000 head of population aged 15 and over.

- 2.

Prior to 1901 Australian divorce data were collected independently by each colonial state and reporting varied from state to state. Consequently reliable Australia-wide figures are not available before 1901.

- 3.

Since 2001 the ABS ceased to collect information on divorce rates based on the married population and this information is now only collected in census years (ABS 2012c).

- 4.

- 5.

The median age of all mothers giving birth increased from an all-time low of 25.4 years in 1971 (ABS 2005b) to an all-time high of 30.8 years in 2006, and has been fairly stable since, with an average age of 30.6 years in 2011 (ABS 2012a). The median age at first birth for mothers in 2011 was younger at 28.9 years (ABS 2012a). Similarly, for men, median age for all births (where the father’s age was known) has increased over this same time period from 28.0 years (ABS 2005b) to 33.0 years in 2011 (ABS 2012a).

- 6.

The ABS’ quinquennial census collects information about marital status (including counts of those separated), but this data is not collected as regularly as the official divorce data and does not provide information about rates of separation each given year.

- 7.

See Appendix for a description of the HILDA survey.

References

Aassve, A., Betti, G., Mazzuco, S., & Mencarini, L. (2007). Marital disruption and economic well being. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 170(3), 781–799.

ABS. (1971). Demography (Cat. no. 3101.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (1979–1993). Divorces, Australia (Cat. no. 3307.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (1994–2001). Marriages and divorces, Australia (Cat. no. 3310.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (1999). Special article: Divorce in the nineties. In Marriages and divorces, Australia (Cat. no. 3310.0, pp. 121–126). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2000). Special article: Lifetime marriage formation and marriage dissolution patterns in Australia. In Marriages and divorces, Australia (Cat. no. 3310.0, pp. 84–91). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2001). Special article: Divorces involving children. In Marriages and divorces, Australia (Cat. no. 3310.0, pp. 101–108). Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2005a). Australian Historical Population Statistics (Cat. no. 3101.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2005b). Births, Australia, 2004 (Cat. no. 3301.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2005c). Divorces, Australia, 2004 (Cat. no. 3307.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2005d). Marriages, Australia, 2004 (Cat. no. 3306.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2006). Household expenditure survey and survey of income and housing: User guide, 2003 – 04 (Cat. no. 6503.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2007). Marriages, Australia, 2006 (Cat. no. 3306.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2009). Divorces, Australia, 2008 (Cat. no. 3307.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2012a). Births, Australia, 2011 (Cat. no. 3301.0).

ABS. (2012b). Divorces, Australia, 2011 (Cat. no. 3307.0.55.001) [electronic product].

ABS. (2012c). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 2011 (Cat. no. 3310.0) [electronic product].

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(4), 1269–1287.

Andreß, H.-J., & Bröckel, M. (2007). Income and life satisfaction after marital disruption in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 500–512.

Australian Parliament House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs. (1998). To have and to hold: Strategies to strengthen marriage and relationships, Parliamentary Paper 95. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Avellar, S., & Smock, P. J. (2005). The economic consequences of the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 315–327.

Axinn, W. G., & Thornton, A. (1992). The relationship between cohabitation and divorce: Selectivity or causal influence? Demography, 29(3), 357–374.

Baxter, J., & McDonald, P. (2004). Trends in home ownership rates in Australia: The relative importance of affordability trends and changes in population composition (AHURI final report 56). Canberra: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute; ANU Research Centre.

Bennett, K. M. (2006). Does marital status and marital status change predict physical health in older adults? Psychological Medicine, 36, 1313–1320.

Bennett, N. G., Blanc, A. K., & Bloom, D. E. (1988). Commitment and the modern union: Assessing the link between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability. American Sociological Review, 53(1), 127–138.

Berrington, A., & Diamond, I. (2000). Marriage or cohabitation: A competing risks analysis of first-partnership formation among the 1958 British birth cohort. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 163(2), 127–151.

Bianchi, S. M., Subaiya, L., & Kahn, J. R. (1999). The gender gap in the economic well-being of nonresident fathers and custodial mothers. Demography, 36(2), 195–203.

Bierman, A., Fazio, E. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). A multifaceted approach to the mental health advantage of the married: Assessing how explanations vary by outcome measure and unmarried group. Journal of Family Issues, 27(4), 554–582.

Bracher, M., Santow, G., Morgan, S. P., & Trussell, J. (1993). Marriage dissolution in Australia: Models and explanations. Population Studies, 47(3), 403–425.

Brockman, H., & Klein, T. (2004). Love and death in Germany: The marital biography and its effect on mortality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 567–581.

Brown, S. L. (2000). The effect of union type on psychological wellbeing: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(3), 241–255.

Brown, S. S., & Booth, A. (1996). Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 28, 668–678.

Burns, A. (1980a). Breaking up: Separation and divorce in Australia. Melbourne: Nelson.

Burns, A. (1980b). Divorce and the children. Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage & Family, 2(1), 17–26.

Butterworth, P., & Crosier, T. (2004). The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: Demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health, 4(44).

Carmichael, G., Webster, A., & McDonald, P. (1996). Divorce Australian style: A demographic analysis (Research School of Social Sciences: Working papers in demography). Canberra: Australian National University.

Carmichael, G., Webster, A., & McDonald, P. (1997). Divorce Australian style: A demographic analysis. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 26(3–4), 3–37.

Carr, D., & Springer, K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(6), 743–761.

de Vaus, D. A. (2004). Diversity and change in Australian families: Statistical profiles. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

de Vaus, D. A., Qu, L., & Weston, R. (2005). The disappearing link between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability. Journal of Population Research, 22(2), 99–118.

DeMaris, A., & Rao, V. (1992). Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability in the United States: A reassessment. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(1), 178–190.

Dupre, M. E., Beck, A. N., & Meadows, S. O. (2009). Marital trajectories and mortality among US adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 546–555.

Dush, C. M. K., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. (2003). The relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts? Journal of Marriage & the Family, 65, 539–549. August.

Funder, K. (1996). Remaking families: Long-term adaptation of parents and children to divorce. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Gove, W. R., & Shin, H.-C. (1989). The psychological well-being of divorced and widowed men and women: An empirical analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 10(1), 122–144.

Grant, M. D., Piotrowski, Z. H., & Chappell, R. (1995). Self-reported health and survival in the longitudinal study of aging, 1984–1986. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 48(3), 375–387.

Hall, D. R., & Zhao, J. Z. (1995). Cohabitation and divorce in Canada: Testing the selectivity hypothesis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(2), 421–427.

Heaton, T. B. (1991). Time-related determinants of marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(2), 285–295.

Heaton, T. B., & Call, V. R. A. (1995). Modeling family dynamics with event history techniques. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 57(4), 1078–1090.

Heaton, T. B., Albrecht, S. L., et al. (1985). The timing of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 47, 631–639.

Hewitt, B., & de Vaus, D. A. (2009). Change in the association between premarital cohabitation and separation, Australia 1945–2000. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 353–361.

Hewitt, B., & Poortman, A.-R. (2010, April 15–17). Household income after separation: Does initiator status make a difference? Population Association of America annual meeting, Dallas, TX.

Hewitt, B., Baxter, J., & Western, M. (2005). Marriage breakdown in Australia: The social correlates of separation and divorce. Journal of Sociology, 41(2), 163–183.

Hewitt, B., England, P., Baxter, J., & Shafer, E. F. (2010). Education and unintended pregnancies in Australia: Do differences in relationship status and age at birth explain the gradient? Population Review, 49(1), 36–52.

Hewitt, B., Voorpostel, M., & Turrell, G. (2012, June 14–16). Relationship dissolution and self-rated health: a longitudinal analysis of transitions from cohabitation and marriage in Australia. Work and Family Research Network inaugural conference. Millennium Hotel Broadway, New York.

Horwitz, A. V., & White, H. R. (1998). The relationship of cohabitation and mental health: A study of a young adult cohort. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(2), 505–514.

Kalmijn, M., & Monden, C. W. S. (2006). Are the negative effects of divorce on well-being dependent on marital quality? Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1197–1213.

Kalmijn, M., Loeve, A., & Manting, D. (2007). Income dynamics in couples and the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 44(1), 159–179.

Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Qu, L., & The Family Law Evaluation Team. (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Kiernan, K. E. (2002). Cohabitation in Western Europe: Trends, issues, and implications. In A. Booth & A. C. Crouter (Eds.), Just living together: Implications of cohabitation on families, children, and social policy. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Klijzing, E. (1992). ‘Weeding’ in the Netherlands: First-union disruption among men and women born between 1928 and 1965. European Sociological Review, 8(1), 53–70.

Lillard, L. A., Brien, M. J., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital dissolution: A matter of self-selection? Demography, 32, 437–457.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2002). First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? A research note. Journal of Family Issues, 23(8), 1065–1087.

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E., & Raczik, A. E. (1993). The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31(3), 247–263.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (2001). The connections between family formation and first-time home ownership in the context of West Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population/ Revue europeenne de demographie, 17(2), 137–164.

Nagato, C., Takatsuka, N., & Shimizu, H. (2003). The impact of changes in marital status on the mortality of elderly Japanese. Annals of Epidemiology, 13, 218–222.

Nock, S. L. (1995). A comparison of marriage and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 16(1), 53–76.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2008). What are equivalence scales? http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/52/35411111.pdf. Accessed 19 Sept 2009.

Ozdowski, S. A., & Hattie, J. (1981). The impact of divorce laws on divorce rate in Australia: A time series analysis. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 16(1), 3–17.

Poortman, A.-R. (2002). Socioeconomic causes and consequences of divorce. Thela thesis, Amsterdam.

Qu, L., Weston, R. E., & de Vaus, D. (2009). Cohabitation and beyond: The contribution of each partner’s relationship satisfaction and fertility aspirations to pathways of cohabiting couples. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(4), 587–601.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). A longitudinal investigation of commitment dynamics in cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 33(3), 369–390.

Schoen, R. (1992). First unions and the stability of first marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 281–284.

Seltzer, J. A. (2000). Families formed outside of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1247–1268.

Seltzer, J. A. (2004). Cohabitation in United States and Britain: Demography, kinship and the future. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 921–928.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smart, C. (2000). Divorce and changing family practices in a post-traditional society: Moral decline or changes to moral practices? Family Matters, 56, 10–19.

Smart, C., & Neale, B. (1999). Family fragments? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Smyth, B., & Weston, R. E. (2000). Financial living standards after divorce: A recent snapshot (Research Paper 23). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Stanley, S. M., Whitton, S. W., & Markman, H. J. (2004). Maybe I do: Interpersonal commitment and premarital or nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues, 25(4), 496–519.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. (2006). Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations, 55(4), 499–509.

StataCorp. (2012). Stata statistical software, release 11.2. College Station: Stata Corporation.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2002). The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey: Wave 1 survey methodology. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

Strohschein, L., McDonough, P., Monette, G., & Shao, Q. (2005). Marital transitions and mental health: Are there gender difference in the short-term effects of marital status change? Social Science & Medicine, 61, 2293–2303.

Summerfield, M., Freidin, S., Hahn, M., Ittak, P., Li, N., & Macalalad, N. (2012). HILDA user manual – Release 11. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne.

Sweeney, M. M. (2010). Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 667–684.

Teachman, J. D., & Polonko, K. A. (1990). Cohabitation and marital stability in the United States. Social Forces, 69(1), 207–220.

Thompson, E., & Collela, U. (1992). Cohabitation and marital stability: Quality or commitment? Journal of Marriage and Family, 54, 259–267.

Uunk, W. (2004). The economic consequences of divorce for women in the European Union: The impact of welfare state arrangements. European Journal of Population/ Revue europeenne de demographie, 20(3), 251–285.

Vogler, C., Brockman, M., & Wiggins, R. D. (2006). Intimate relationships and changing patterns of money management at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The British Journal of Sociology, 57(3), 455–482.

Wade, T. J., & Pevalin, D. J. (2004). Marital transitions and mental health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 45(2), 155–170.

Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. (2000). SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln: Quality Metric Incorporated.

Wiik, K. A., Keizer, R., & Lappegård, T. (2012). Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 389–398.

Willets, M. C. (2006). Union quality comparisons between long-term heterosexual cohabitation and legal marriage. Journal of Family Issues, 27(1), 110–127.

Williams, K., & Umberson, D. (2004). Marital status, marital transitions, and health: A gendered life course perspective. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 45(1), 81–98.

Willitts, M., Benzeval, M., & Stansfeld, S. (2004). Partnership history and mental health over time. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 53–58.

Wood, R. G., Goesling, B., & Avellar, S. (2007). The effects of marriage on health: A synthesis of recent research evidence. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Wu, Z., & Hart, R. (2002). The effects of marital and non-marital union transition on health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 420–432.

Wu, Z., Penning, M. J., Pollard, M. S., & Hart, R. (2003). In sickness and in health: Does cohabitation count? Journal of Family Issues, 24(6), 811–838.

Yamaguchi, K. (1991). Event history analysis. Newbury Park: Sage.

Zhang, Z., & Hayward, M. D. (2006). Gender, the marital life course, and cardiovascular disease in late midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 639–657.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix 5.1: Methodological Notes

Appendix 5.1: Methodological Notes

The data used to examine dissolution from cohabiting relationships came from the first ten waves of The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, collected between 2001 and 2010 (see Technical Appendix).

The sample for Table 5.1 included all respondents at wave 1 who indicated that they had married. The analysis was restricted to those in their first marriage as the processes of divorce surrounding remarriages are very different from those of first marriages (Carmichael et al. 1997; Sweeney 2010). Retrospective marriage history data were used. As only first marriages are under consideration in this analysis, if a respondent had married once the information about their present marriage was included in the calculation of the dependent variable. If the respondent had been married more than once then information about their first marriage was included but not information about subsequent marriages.

The sample for Table 5.2 and Figs. 5.6 and 5.7 includes respondents who formed a cohabiting or marital relationship between 1995 and 2010. Prior to 2000 retrospective relationship history data are used, and after 2000 panel data were used. If a respondent had formed more than one cohabiting relationship during that time we included their most recent or current cohabiting relationship. We restricted the marriage sample to those who entered their first marriage only. People who were cohabiting after marriage were also excluded from the analytic sample. To capture the main relationship processes identified by previous research (Qu et al. 2009), we differentiated between marriages, cohabitations that ended in marriage and cohabiting only relationships.

The sample for the analysis presented in Figs. 5.8, 5.9 and 5.10 includes all respondents in HILDA waves 1–10 who were married or cohabiting at wave 1 or who married or started cohabiting during the panel. We follow them over the panel and observe those relationships that end in separation. The model for Fig. 5.10 includes controls for relationship duration, age, employment status, highest level of education, and number of children in household 50 % or more of the time. The models for Figs. 5.9 and 5.10 include a range of basic controls including relationship duration, age, number of children under 18 in the household 50 % or more of the time, household income, employment status, highest level of education and health status at the previous wave.

Given that we had repeated observations on individuals over time, the structure of our data violates the assumption of independent observations and ordinary least squares regression would not be appropriate. Instead we used a linear fixed-effects model to account for clustering of observations by individual and control for between individual variation (Singer and Willett 2003). This approach is also appropriate for unbalanced panels. The fixed-effects model controls for unobserved heterogeneity because it produces estimates that are net of all observed and unobserved differences between individuals that are time-invariant. Models were estimated using the fixed effects option in xtreg in STATA 11.2 (StataCorp 2012).

For the results presented in Fig. 5.8, we use equivalised disposable annual household income as our main dependent variable. Our income measure was equivalised using the OECD-modified equivalence scale (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008). In this approach the first adult within the household is assigned a value of 1, a value of 0.5 is assigned to each additional adult member (aged 15 or over) and a value of 0.3 is assigned to each child. We used this scale as it is the equivalence scale considered best suited to the Australian situation by the ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006). Preliminary analyses showed that using alternative equivalence scales, such as dividing income by the square root of the number of household members, did not lead to different conclusions. In addition we excluded extreme outliers on household income; respondents who reported a household income (not equivalised) of more than $300,000 AUD each year.

For Figs. 5.9 and 5.10 we used the mental and physical health domain measures derived from the Short-Form 36 (SF-36). The SF-36 is a self-completed measure of health status comprising 36 items that measure two main health domains as well as eight health constructs and is a well-validated tool for measuring population health (McHorney et al. 1993; Butterworth and Crosier 2004). For physical and mental health domains, scale scores ranged from 0 to 100, where lower scores indicated poor health and higher scores indicated excellent health (Ware et al. 2000).

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hewitt, B., Baxter, J. (2015). Relationship Dissolution. In: Heard, G., Arunachalam, D. (eds) Family Formation in 21st Century Australia. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9279-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9279-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9278-3

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9279-0

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)