Abstract

Seven hundred and fifty-three observations were collected on 25 adolescents at random times during an average week. The observations consisted of self-reports completed in response to an electronic pager. The study was aimed at the question: What is the experience of time alone like for adolescents? The results suggest a complex but consistent relationship: while aloneness is generally a negative experience, those adolescents who spend a moderate amount of time alone (about 30 % of their waking time) tend to show better overall adjustment than adolescents who are either never alone or spend more than the optimal proportion of time alone. Alienation and average moods showed inverse linear or quadratic relationships with amount of time alone. These results are discussed in terms of the possible psychosocial functions of aloneness at the adolescent stage of the life cycle.

This research was funded through PHS grant No. RO1 HM 22883-02. Requests for reprints should be sent to Reed Larson, Committee on Human Development, University of Chicago, 5730 S. Woodlawn, Chicago, Illinois 60637.

Reprinted from the Journal of Personality, vol 46, no 4, pp. 677–693, Dec 1, 1978. Copyright © 1978 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

If you wish to reuse your own article (or an amended version of it) in a new publication of which you are the author, editor or co-editor, prior permission is not required (with the usual acknowledgements).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Diametrically opposed opinions are held about the psychological value of spending time alone. Thinkers from Petrarch to Rousseau, William Penn to Tillich have praised time alone as a vehicle of self-discovery, creative insight, and spiritual inspiration. Pascal states the case most concisely: “I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chambers” (cited by Halmos 1952). Recent theoretical work on privacy suggests that voluntary aloneness can have a number of positive attributes (Westin 1967; Altman 1975).

The opposing view regards the source of contemporary man’s alienation to be in his physical and emotional isolation from others. Frequent withdrawal of people into a state of aloneness, encouraged by an ideology of privacy and reserve, is seen as the core of the modern problems of loneliness and social disintegration (e.g., Halmos 1952; Aries 1960; Sullivan 1953). The experiences of prisoners and social isolates are a common source of evidence to support this view.

The disagreement seems to reflect different emphases placed on the motivation for being physically separate from others. The first point of view conceives solitude to be a chosen state productive of creativity and self-affirmation. The second looks at loneliness as an unchosen state leading to depression and alienation. But there are no systematic data describing the effects of aloneness in everyday life, let alone testing different effects of voluntary versus involuntary aloneness.

The arguments of this debate have a magnified relevance for persons at the adolescent stage of the life cycle. It is a time when the option of being alone is first being accepted without anxiety (Coleman 1974). But it is also a time when the influences of peers and family are indispensable to what one is and how one thinks (Costanzo 1970; Sherif and Sherif 1961). It is also a time when the distinction between public and private experience is first being realized (Wolfe and Laufer 1974), and when the existential human condition of aloneness first becomes accessible to thought (Chandler 1975). Adolescents face the developmental tasks of establishing autonomy from parents (Douvan and Adelson 1966), synthesizing a sense of identity and beginning to deal with the issue of intimacy and isolation (Erikson 1968). Intermittent solitary time may be useful or even necessary for these formative processes (Wolfe and Laufer 1974; Ittelson 1974). The time an adolescent spends alone may serve for monitoring growth, experimenting with different selves, dealing with emotional conflicts, and etching out a sense of personal identity. On the other hand, it may be that such time in solitude establishes patterns of isolation and loneliness.

This chapter asks three main questions about the nature of time alone in adolescents’ lives. First: How do they experience themselves when they are alone? Is it a strong, active, creative experience or is it more likely to be a weak, passive, despondent one? Second: How does choice mediate the effects of aloneness? Is solitude (or voluntary aloneness) a different experience from loneliness (or involuntary aloneness)? Third: How do adolescents who spend more or less time in this state of aloneness differ? Is spending time alone associated with integration of personality or with alienation from self and others?

The new method of experiential sampling is an ideal source of data for dealing with these types of questions (Prescott et al. 1976; Csikszentmihalyi et al. 1977). It provides close estimates of how much time people spend alone throughout a normal day, and it provides random cross-sections of daily experiences.

Method

Procedure

The data were obtained from a sample of adolescents, each of whom filled out self-report forms at random times during the waking hours of a normal week, the scheduling of self-reports was controlled by one-way radio communication. Each subject carried a pocket-sized electronic paging device on his person for a period of 1 week. Radio signals with a 50-mile transmission radius were emitted from a central location according to a predetermined random schedule. These signals caused the receivers to make a series of audible “beeps,” which served as the stimulus for subjects to complete the self-report forms.

The schedule specified 5–7 signals per day at random times between the hours of 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 p.m. All seven days of the week were included in the schedule. The 42 signals per week were transmitted according to the same random pattern to each subject, although the sequence differed depending on which days of the week a subject started, Seven hundred and fifty-three records were collected during the months of February and March, 1976.

Sample

The sample consisted of 25 unpaid subjects obtained through personal contacts by graduate students in a course on adolescence. Αll lived in the Chicago area. Their ages ranged from 13 to 18, with a median age of 14. There were 16 girls and 9 boys. Sixteen of the subjects were white; 6 were black; 3 were of Spanish-American descent. A substantial minority of the subjects, 40 %, lived with only one parent; the rest lived with both. All subjects had at least one sibling. Socioeconomic status of the guardian was coded according to Hollingshead’s two-factor scale. The sample was skewed toward the highest class (32 %), with only 3 subjects (12 %) in the lowest class. The intermediate classes contained 5, 4, and 5 subjects respectively. The 25 subjects filled out a total of 753 self-report records. The range of completed records was 21–38 records per person, with an average of 30. Subjects responded to approximately 89 % of the signals by filling out records. The data set does not include 11 % of the sample activity. Informal reports suggest that some subjects turned the receivers off or failed to respond when sleeping, taking a test, engaging in a sport such as swimming where the receiver could not be kept on their person, or when they just did not feel like filling out a form, Omissions also occurred when subjects left the receiver or the forms at home, and when subjects travelled beyond the signal transmission range.

The Self-Report Form

Subjects were provided with bound booklets of 50 identical forms. Each form consisted of two sides of a page containing items that required approximately 2 min to complete.

-

(a)

Time Alone. At the time of the signal this was established by the question, “Were you: alone, with friends or acquaintances, with family, with strangers, other.” The percentage of an individual’s records which had been marked “alone” served as an estimate of the amount of time he or she typically spent alone. A substantial (r = 50) correlation between the amount of time subjects spent alone in the first and last half of the study period indicates that this is a relatively stable feature of their life style.

-

(b)

Emotional States. A group of 13 items solicited semantic differential ratings of mood and physical state. Subjects were asked to rate which of two opposite adjectives best described their state at the time they were signaled. The ends of the 7-point scale corresponded to extreme opposing states, such as “hostile” versus “friendly,” “happy” versus “sad.” For each individual a mean rating was computed for each of these 13 scales. These means served as indices of subjects’ average daily emotional state.

-

(c)

Involvement. Another group of items was designed to measure the quality of the subjects’ involvement in the situation. Ten-point scales from “low” to “high” were provided for rating “challenges of the activity,” “your skills in the activity,” “Do you wish you had been doing something else?” and “Was anything at stake for you in the activity?” Similar 10-point scales were provided for rating “How well were you concentrating?” “Was it hard to concentrate?” “How self-conscious were you?” and “Were you in control of your actions?” As with the 13 mood scales, the mean rating was computed for each of these items, for each individual, to serve as indices of the average quality of their interaction with the environment.

-

(d)

Activities. The self-report form contained open ended questions asking subjects where they were when they were signaled and what they were doing. Responses to these questions were coded into a limited number of inclusive categories of environments and activities. For roughly two-thirds of the records subjects were coded for a secondary as well as a primary activity.

-

(e)

Motivation. Subjects were also asked “why were you doing this?” to which they were to respond by checking either I had to do it: Yes–No” or “I wanted to do it: Yes–No.” The item “do you wish you had been doing something else?” provided a third assessment of the motivation for their current behavior. Though none of these three items specifically asks whether the individual wanted to be alone or with others, they are used here as indicators of whether aloneness was voluntary or involuntary. Of course self-reports are far from ideal indices of motivation (Nisbett and Valins 1972; Ross 1977) and a neat division of daily actions into those which are voluntary and involuntary might not reflect the way daily choices are actually made. Despite their limitations, these repeated measures of motivation provide the best available index of whether a person was alone by choice or by necessity.

-

(f)

Alienation. Subjects were administered the Maddi Alienation Index (Maddi et al. 1976). This index provides subscores for five domains of alienation and a total alienation score.

Results

The Context of Time Alone in Adolescence

During the study period, this group of adolescents spent nearly a third (29 %) of their waking time alone. 44 % of the records were marked “with friends and acquaintances” and 20 % were marked “with family.” The responses “with strangers” and “other” were marked the remaining 7 % of the time.

Several activities were reported more often alone than with others (Table 13.1a). Free-floating thought (fantasizing, day-dreaming, talking to self, thinking about past or future) was more commonly recorded as an activity when subjects were alone. Involvement in forms of passive entertainment other than watching T.V. (listening to records or the radio, reading newspapers, magazines, or books) occurred more frequently when subjects were alone. Sleeping and personal grooming were also associated with being alone. These data give a clear impression that, when by himself, an adolescent is more likely to be engaged in reflection or involved in the activities such as passive entertainment and grooming, which are compatible with free-floating thought.

As Table 13.1b shows, the bedroom was the most common context for this solitude. Table 13.1c suggests that activities alone were no more likely to be involuntary than activities with others. Subjects were alone most frequently between the hours of 5:00 and 6:00 p.m. and the hours of 9:00 and 11:00 p.m. There were no marked differences among the days of the week in the proportion of time spent alone.

The Experience of Time Alone in Adolescence

There are substantial differences between subjects’ self-ratings when they are alone and when they are with others (Table 13.2). The most consistent differences are on the 13 mood items. Alone, respondents are much more lonely and hostile. They are significantly less happy and less alert. Further, they rate themselves as weaker and more passive. Only four mood items: relaxed-tense, trusting-suspicious, creative-dull, and free-constrained, fail to reflect the negative tone of the experience of being alone.

The quality of involvement items qualify this picture somewhat. Respondents report feeling less self-conscious, having higher skills, and having less difficulty concentrating when alone.

An issue raised by Table 13.2 is whether this pattern of negative moods is due to aloneness per se or to other factors associated with aloneness. The following analyses consider the contribution of these other factors. Table 13.3 reports how the three most significant moods change when respondents are alone or with others in different activities, environments, and motivational states. It shows that the association of negative mood to aloneness holds within most activities, particularly for passive entertainment, eating, walking and studying. But being alone appears not to be related to mood when subjects were thinking, talking, grooming, or working. The strong positive moods associated with talking (on the phone) when physically alone suggests that conceptually this condition would be classified more appropriately as being with others.

Table 13.3b also shows that within specific environments the association between aloneness and negative moods is generally sustained. Regardless of environment, subjects report being less hostile and lonely if they are with others. The trend for alert-drowsy is in the same direction, though less strong.

The mediating effects of motivational states are rather complex but consistent (Table 13.3c). They can be summarized as follows:

-

(a)

When a person is doing something by choice, his or her moods are more positive than when the activity is forced.

-

(b)

When a person is engaged in a voluntary activity, his or her moods are significantly more negative alone than with others.

-

(c)

When a person is engaged in an involuntary activity, moods are not affected by being alone or with others.

These relationships, however, do not fully cover the range of motivation and affect which lead to a person’s decision to be alone or with others. It is possible that negative moods lead to a choice of being alone, rather than aloneness to negative moods. This issue can be dealt with by examining changes of moods in a time series. Table 13.4 presents data on 37 pairs of sequential records where subjects went from being with others to being alone and 28 pairs where they went from being alone to being with others, This sample includes all such pairs of transition records which were obtained within 120 min of each other. They include a representative range of persons (20 in the first case, 17 in the latter), times of day, activities, environments, and motivational conditions. In comparison to Table 13.2, it can be seen that moods are no lower than usual prior to being alone; if anything, they tend to be more positive. Table 13.4 shows that it is after transition to being alone that moods drop. The items reflecting the biggest change (e.g., happy-sad, sociable-lonely, self-conscious) are the same items found to be strongly associated with aloneness in Table 13.2. The implication is that negative moods alone are a result of being alone, rather than aloneness being a product of negative moods, Consistent with this interpretation, the right side of Table 13.4 shows self-ratings improving when subjects go from aloneness to being with others.

Another factor which might produce differences in self-ratings between times alone and times with others is the method itself. The pager is a novel stimulus to a subject’s friends, family, and other associates. Initially it may generate curiosity and special interest among them, which could conceivably affect a subject’s response. If this artifact were a significant factor it could be expected that the differences in self-ratings alone and with others would disappear or be substantially reduced by the second half of the week, when the novelty had worn off. However, this is not the case. In the second half, moods alone remain significantly different from moods with others, Multivariate f(13, 10) = 4,27, p < 0.02, and ratings of quality of involvement alone and with others are also significantly different, Multivariate f(7, 16) = 5.52, p < 0.003.

Individual Differences: Correlates of Time Spent Alone

Major differences existed between individuals in the amount of time they spent alone. One person was never alone; at the other extreme one individual was alone for 57 % of the times sampled. The mean and median percentage of time alone was 29 %. There were no sex differences in these proportions. However, significantly more time was spent alone by older (p < 0.05) and higher socioeconomic status (p < 0.04) subjects. Those spending differing proportions of time alone showed approximately the same profiles of activities alone, environments at aloneness, and time of day of aloneness (as in Table 13.1).

The percentage of time which subjects spent alone was found to be related to other aspects of their life styles. It is intrinsically related, of course, to the amount of time spent with others. The data suggest that the time spent alone is primarily obtained at the expense of time spent with family rather than time with friends, Time alone has a high negative correlation to time “with family” (r = −0.52, p < 0.01), while being less related to proportion of time “with friends or acquaintances” (r = −0.32, n.s.). Subjects who spent more time alone also spent less time talking with peers (r = −0.43), p < 0.05), less time playing sports or games (r = −0.31, n.s.), and less time in non-school public environments (r = −0.42, p < 0.05). However, these last three relationships may be partially attributable to SES and age, as is indicated by the reduced correlations when these variables are controlled (respectively: r Partial = −0.28, n.s.; r Partial = −0.18, n.s.; r Partial = −0.33, n.s.).

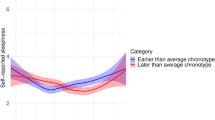

An unexpected set of findings emerged when the characteristics of persons who spent much time alone were examined. Table 13.2 had shown that being alone was generally a negative experience. Yet adolescents who spent more of their time alone tended to report higher average moods over-all. Ten of the 13 mood variables were positively correlated with proportion of time alone, four at a significant level. When controlled for age and SES, adolescents who spent more time alone were found to rate themselves significantly more friendly (r = 0.46) and more excited (r = 0.37) than adolescents who spent less time alone.

Correlations between alienation and amount of time spent alone were not significant, but inspection of the scattergram suggested a curvilinear distribution. To test this relationship the data were fitted to a quadratic equation of the form,

where x is the proportion of time an individual spent alone, y is the person characteristic of interest (e.g., alienation) and β 0, β 1, and β 2 are constants found to minimize squared error. An F test was used to evaluate whether these parabolic functions were a significantly better fit to the data (explained more variance in y) than the simple linear functions represented by Pearson product moment correlations.

All fitted curves were found to be U-shaped, Subjects at the extremes, those who spent no time alone and those who spent very much time alone were the most alienated. Significant curvilinear trends were found for 4 out of 5 alienation subscales (Table 13.5). The clearest relationship is shown between “interpersonal alienation” and proportion of time spent alone. The curves suggest that adolescents who spend optimal intermediate amounts of time alone (32–37 %) are the least alienated.

Table 13.6 attempts to capture unique characteristics of this group of adolescents who spent an intermediate amount of time alone. However, it shows that they are as likely to be involuntarily compelled in their activities as are other subjects—whether they are alone or with others. This suggests that the low aloneness and high aloneness of the other two groups of subjects is not a result of forces beyond their control. Further, the intermediate aloneness group does not differ from the others in their reported experience alone. Relative to time with others, they are not significantly more friendly, alert, or sociable alone. They also do not differ in age, sex or SES from the other groups.

Discussion

Schopenhauer addressed the controversy between those idealizing aloneness and those idealizing sociability with an analogy to shivering porcupines. When they are too close these porcupines suffer from each others’ pricks, and when too far apart they suffer from cold. A medium distance provides a moderate measure of freedom from both unpleasantnesses (cited by Halmos 1952). Although this analogy oversimplifies the pattern found, it nicely expresses its paradoxical nature and the inadequacy of extreme points of view.

It is worth noting that those who have commented on the value of privacy which is an overlapping but separate concept from the one used here (Altman 1975; Ittelson 1974), have also rejected extreme points of view, arguing for an optimal intermediate amount of privacy (Altman 1975; Schwartz 1968; Goffman 1956; Bates 1964).

The data suggest that adolescents have more negative emotional states alone than with others. They are less happy, less alert, and more lonely. Further analysis indicates that this negative state is not a result of the activities they do alone or the environments in which aloneness occurs, but appears to be a direct result of aloneness per se.

Adolescents seem to choose to be alone as often as they choose to be with others. While the data do not capture the full dimensions of choice, they suggest that being alone is likely to be voluntary. This choice does not appear to be a result of a preexistent negative mood. Emotional states prior to being alone are as high as at any other time. The drop in mood occurs after one leaves the presence of others. And, surprisingly, it is at times when aloneness is associated with a voluntary choice of activity that this drop in mood is greatest.

Why adolescents might choose this more negative state is suggested by comparisons between subjects. Those who spend at least some proportion of time alone are less alienated from themselves and others. But much time spent alone, like no time spent alone, is associated with greater alienation.

The paradox is that a negatively experienced state, aloneness, is associated with a positive trait, lower alienation. Aloneness appears to be analogous to a medicine which tastes bad, but leaves one more healthy in the long run. The negative moods, therefore, may be a superficial veneer for more important processes. The data suggest what these may entail. A person alone is less self-conscious and has a higher perception of his or her own skills. Being alone is a time when mental reflection is more common—an activity for which the negative differential in moods does not hold. Grooming and listening to music, which may also be reflective activities, are also more frequent alone.

These findings suggest that potential positive features of aloneness, identified by experimental and theoretical literature, are being exploited in people’s daily lives. Aloneness has been found under some conditions to enhance creativity (Taylor et al. 1958) and memory (Zuckerman et al. 1968). Theoretical work on privacy proposes that aloneness provides opportunities for emotional release, for a reflective integration of one’s life, and for experimentation with different selves (Westin 1967; Altman 1975; Ittelson 1974). More frequent mental reflection and related activities alone indicate that this time might be used for integrative thought and rehearsal of different selves. These opportunities have a special value for adolescents who face the developmental task of establishing autonomous identities.

Adolescents who spend very little time alone could be deprived of these opportunities, and as a result might engage in fewer integrative thought processes, this being reflected in greater alienation. At the other extreme, adolescents who spend too much time alone might lack affiliative and socializing contact with others, which also results in greater alienation. While this interpretation seems most parsimonious with the findings, additional evidence is clearly needed before alternate causal or reciprocal interrelationships between these variables can be excluded.

Summary

This study has revealed that the experience of aloneness in the daily lives of adolescents cannot be simply characterized as a voluntary positive state or an involuntary negative state. It is no more associated with choice or compulsion than is being with others. The data indicate that the emotional experience of time alone is generally more negative. However, it also suggests that this time is used for mental reflection, which we have inferred serves an important integrative function, at least for adolescents, if not for adults. The value of this experience alone is suggested by the finding that those adolescents who spend an intermediate amount of their time alone during a typical week are least alienated.

References

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

Aries, P. (1960). Centuries of childhood (R. Baldick, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

Bates, A. (1964). Privacy—a useful concept? Social Forces, 42, 429–434.

Bock, R.D. (1975). Multivariate statistical methods in behavioral research. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Chandler, M. (1975). Relativism and the problem of epistemological loneliness. Human Development, 18, 171–180.

Coleman, J. (1974). Relationships in adolescence. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Costanzo, P. (1970) Conformity development as a function of self-blame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 14, 366–374.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Larson, R., & Prescott, S. (1977). The ecology of adolescent activity and experience. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 6(3), 281–294.

Douvan, E., & Adelson, J. (1966). The adolescent experience. New York: Wiley.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Goffman, E. (1956). The nature of deference and demeanor. American Anthropologist, 58, 473–492.

Halmos, P. (1952). Solitude and privacy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ittelson, W. (1974). An introduction to environmental psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Maddi, S., Kobasa, S., & Hoover, M. (1976). The alienation-commitment test: reliability and validity. Unpublished Manuscript

Nisbett, R., & Valins, S. (1972). Perceiving the causes of one’s own behavior. In E.Jones (Ed.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Morristown: General Learning Press.

Penn, W. (1909). Fruits of solitude. In Harvard classics (Vol. 1). New York: P. F. Collier & Son.

Petrarch, F. (1924). The life of solitude (J. Zeitlein, Trans.). Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Prescott, S., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Graef, R. (1976). Environmental effects on cognitive and affective states: The experimental sampling approach. Unpublished manuscript.

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 13). New York: Academic Press.

Rousseau, J. (1971). The reveries of a solitary (J. Fletcher, Trans.). London: George Routledge and sons.

Schwartz, B. (1968). The social psychology of privacy. American Journal of Sociology, 73, 741–752.

Sherif, M., & Sherif, C. (1961). Reference groups. Chicago: Regnery.

Sullivan, H. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Taylor, D., Berry, P., & Block, C. (1958). Does group participation when using brain-storming facilitate or inhibit creative thinking? Administrative Science Quarterly, 3, 23–49.

Tillich, P. (1956). The eiernal now. New York: Charles Schribner’s Sons.

Westin, A. (1967). Privacy and freedom. New York: Atheneum.

Wolfe, M., Laufer, R. (1974). The concept of privacy in childhood and adolescence. In D. Carson (Ed.), Man-environment interactions: Evaluations and applications (part II). Stroudsburg: Halsted Press.

Zuckerman, M., Persky, H., Link, K., & Basu, G. (1968). Experimental and subject factors determining responses to sensory deprivation, social isolation and confinement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 73, 183–194.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Larson, R., Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Experiential Correlates of Time Alone in Adolescence. In: Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9094-9_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9094-9_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9093-2

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9094-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)