Abstract

The publication of the book so-called “Manual of the Sanities” (Peterson and Seligman, Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification, vol. xiv. Oxford University Press, New York, 2004) has inspired the scientific study of individuals’ positive traits with different populations from different countries. Studies conducted in Argentina (general and military population) in relation to the pillar of positive traits are shown. An inventory of complex bipolar items was developed to measure character strengths. This self-report inventory – that covers a broad range of strengths of character with few items – has demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability and validity. Relationships that have been informed in previous studies between character strengths and empirical and theoretically linked constructs such as satisfaction with life, personality and social desirability, were also found using this inventory. Moreover, studies on character strengths have been conducted with Argentinean military students (cadets). There was found that character strengths reliably discriminate between junior and senior students, and that character strengths are predictors of academic and military performance at the beginning and final stage of the military course. Results from Argentina have shown original aspects compared to studies done in other countries.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

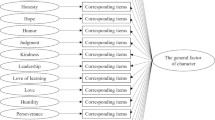

The study of positive personal traits or character strengths did not start with the emergence of Positive Psychology, but many decades ago. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, the study of moral character was part of the mainstream psychology (McCullough & Snyder, 2000). At that time, the terms “character” and “personality” were used in similar manner in psychology. Gordon Allport was one of the most important driving forces for the exclusion of the term character and its study from the psychological field. Instead, he proposed the study of personality, i.e., the characteristics of individuals from an objective perspective (Cawley, Martin, & Johnson, 2000; McCullough & Snyder, 2000; Nicholson, 1998; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Since the 1940s, both the character term and the character study were almost removed from psychology. However, at the edge of the twenty-first century, an unifying movement for the study of character emerged, led by the creation of the Values in Action Institute (VIA) and the publication of the “Manual of the Sanities” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), a book developed as the positive counterpart of the manuals of mental disorders. Peterson and Seligman considered the character construct as composed by virtues, strengths and situational themes, in a decreasing level of abstraction (see Fig. 6.1) and developed a character classification of 24 character strengths and 6 virtues (see Table 6.1).

The character classification from the Manual of the Sanities has inspired several research on the association between positive traits and a wide variety of variables such as, genetics (Steger, Hicks, Kashdan, Krueger, & Bouchard, 2007), sex and age (Linley et al., 2007), social groups (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012), satisfaction with life (Park, Peterson, & Seligman 2004), personality (Macdonald, Bore, & Munro, 2008), academic performance in college students (Lounsbury, Fisher, Levy, & Welsh, 2009), academic and military performance in military students (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012), recovery from illness (Peterson, Park, & Seligman, 2006), and posttraumatic growth (Peterson, Park, Pole, D’Andrea, & Seligman, 2008), among cixothers.

2 The Strength of Character Inventory

The need to solve a practical problem related to the lack of a scale for studying positive traits in Argentina led to the development of a reliable and valid assessment instrument for measuring strengths of character according to Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) classification.

2.1 Justification for the Development of the Strength of Character Inventory

2.1.1 Not Available Measurement Instrument

We considered several alternatives to solve the problem of not having a reliable and valid instrument to assess character strengths of the VIA classification with the Argentinean population (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). An imaginable solution was to develop an adaptation of the English or the Spanish version of the instrument developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004). That is, the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) that assess 24 character strengths. However, it was decided not to use the VIA-IS because: (a) its length, the VIA-IS consisted of 240 items that implies monitor participants to prevent the effect of dispersed attention (Peterson & Seligman, 2004); and, (b) its duration, the VIA-IS demands 1 h approximately with military population (Matthews, Eid, Kelly, Bailey, & Peterson, 2006), that would not satisfy time constraints for conducting a study with Argentinean military population. Thus, it was considered as a reasonable solution to use a brief 24-item measurement instrument consisting of self-nominations that corresponded to the 24 character strengths. These scores tended to converge with its corresponding VIA-IS scale scores (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The developers of VIA-IS have warned against the use of self-nominations, because a simple and abstract label of a trait could be interpreted in an idiosyncratic manner by participants, while explicit expressions of items in a questionnaire, overtly present thoughts, feelings and behaviors that correspond to a given strength. Therefore, we aimed to develop a short measurement instrument to assess the 24 strengths of the VIA classification that exceeded the criticism raised by Peterson and Seligman: (a) it should not be an instrument of self-nomination, and (b) it should include thoughts, feelings, and behaviors representing various manifestations of the character strengths.

2.1.2 Complex Items

In a first approach, we were skeptical about solving the problem of developing a short instrument which includes the plethora of thoughts, feelings and behaviors that correspond to a given strength, because measurement instruments are usually developed in a manner where each item consists of a simple sentence that expresses a very specific aspect (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). However, there is an unusual form to construct assessment instruments – developing items that consist of paragraphs or sentences. For example, such kind of instruments are used to assess personality traits relevant to personality disorders (Harlan & Clark, 1999), types of attachment (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Hazan & Shaver, 1987), or personality dimensions from the lexical hypothesis (e.g., measurement instruments recently developed, Woods & Hampson, 2005; or in the origins of the lexical hypothesis, Cattell, 1947; Fiske, 1949; Norman, 1963; Norman & Goldberg, 1966; Tupes, 1957; Tupes & Christal, 1958, 1961). Particularly, the pioneers of lexical hypothesis included assessment instruments consisting of complex items in several empirical that served as grounded basis for the Big Five personality model. Moreover, instruments of complex items are being used and included in recent studies. For instance, Herzog, Hughes, and Jordan (2010), and Levy and Kelly (2010) used the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) to assesses attachment types; Stroud, Durbin, Saigal, and Knobloch-Fedders (2010), and Wilt, Schalet, and Durbin (2010) used the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality Self-Description Rating Form (SNAP-SRF; Harlan & Clark, 1999) to assesses personality traits; and Bäccman and Carlstedt (2010) and Want, Vickers, and Amos (2009), included the Single-Item Measures of Personality (SIMP; Woods & Hampson, 2005) to measure the dimensions of the Big Five.

2.1.3 Single Bipolar Items

Similarly to the RQ and to the SIMP that present one item per variable, we wanted to develop a new tool to assess the VIA character strengths with a minimum length. That is, one item assessing only one character strength (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). Several authors – e.g., Harlan and Clark (1999), the pioneers of the lexical hypothesis mentioned above, and more recently Woods and Hampson (2005) who investigate on this model – used measurement instruments with items that consisted of two complex paragraphs or sentences with opposing meaning about personal descriptions. Consequently, we chose this procedure for developing items for the new instrument to assess character strengths. As a result, we developed 24 bipolar paragraph-items consisting of two opposing descriptions. We also had to define the characteristics of the item poles of the new instrument to measure the strengths of character from the “Manual of the Sanities” (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). Peterson and Seligman (2004) had argued that, in all cases, the focus should be centered on the positive side of character strengths. Therefore, the assessment should be within the positive range, that is, from the maximum presence to a total absence of a given character strength. Consequently, each item should contrast a pole of presence with a pole of absence of a given character strength. For instance, the description of the presence of kindness would express thoughts, feelings and behaviors of a good person as opposed to the description of the characteristics of a person without kindness, but not the characteristics of an individual with a persistent and pervasive bad attitude.

2.1.4 Item Contents

In order to achieve high levels of internal consistency for the contents of each item of the new inventory (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b), the development of description of personal characteristics that compose each item had to be subordinated to both rational and empirical constraints. Its content should validly refer to one character strength and should reliably be associated with empirical studies. This strategy is similar to the procedure used by Harlan and Clark (1999) to develop the SNAP-SRF based on the original SNAP consisting of 375 items; or by Cattell (1947), the intellectual father of the Big Five, who at the beginning of the lexical approach developed 35 descriptive paragraphs from the empirical and semantic analyses of thousands of terms referring to personality traits (Cattell, 1943; Goldberg, 1993). Consequently, with the purpose of developing bipolar items for the new instrument, we analyzed consensual definitions of the character strengths from the “Manual of the Sanities” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and read questionnaires derived from these definitions and classification, such as the English and the Spanish versions of the VIA-IS, both online and paper-and-pencil format (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). Specifically, items that correspond to each of the 24 Revised IPIP-VIA scales (http://ipip.ori.org/newVIAKey.htm) with Cronbach alpha >.70 were adapted and used as a reference for developing each of the descriptions that represent the presence of a given character strength.

Regrading items’ wording, we developed paragraphs with simple vocabulary and grammar (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). To generate bipolar items, we developed for each description of the presence of a given character strength its corresponding description of absence of this strength in which the elements of the sentence describing presence were semantically denied, trying to maintain sequential order, grammatical structure, and lexicon of the original paragraph.

Subsequently, we arranged the 24 bipolar items in a counterbalanced manner (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008b). Due to this counterbalance, half of the items would be directly scored and the other half would be reversely scored. Finally, we added below each bipolar item, a 5-point Likert scale where participants had to indicate the degree of agreement with one or the other description, i.e., to the description of an individual with presence of a particular strength or the description of an individual without that strength. We named the new measurement instrument as ‘Strength of Character Inventory’ (SCI, IVyF in Spanish). Table 6.2 shows an example of the item that measures the character strength of persistence.

2.2 General Characteristics of the Strength of Character Inventory

Due to the characteristics outlined above, the SCI is an instrument composed of global direct self-rating items. Paulhus and Vazire (2007) considered this type of inventories as the simplest form of self-report, and its central features are clarity —high face validity— and simplicity. In this sense, Burisch (1984) has argued that there is consistent empirical evidence, not broadly known, that demonstrates that self-rating instruments are, in general, more valid than questionnaires. Moreover, there are other positive aspects of the short self-rating instruments, such as direct communicability; economy in construction and application; and quickness to be filled out by the respondents, implying lower levels of fatigue and boredom for research participants (Burisch, 1984; Paulhus & Vazire, 2007; Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001).

In sum, the SCI consisting of 24 bipolar paragraphs-items, has a 10 % item-length in comparison to VIA-IS, and solve the problem of item interpretation explained by Peterson and Seligman (2004) in relation to short measurement instruments. Moreover, the SCI presents validity and internal consistency of its contents.

The SCI was administered to a pilot sample of 48 third-year cadets of the Argentine Army. Generally, cadets filled out the measurement instrument in less than 30 min and properly understood the items and the structure of the inventory. Subsequently, the instrument was administered to two different groups of college students obtaining similar results.

2.3 Psychometric Properties of the Strength of Character Inventory

In the next paragraphs it is shown that, despite being a short measurement instrument, the SCI presents psychometric characteristics similar to the psychometric characteristics observed for VIA-IS of 240 items.

2.3.1 Reliability

Firstly, a Cronbach alpha of .85 was found for the scores of the 24 items that measure the 24 character strengths of VIA classification (cf. Macdonald et al., 2008) in a general population sample of 781 individuals (453 women), with a mean age of 40.9 years, SD = 16.7 (Cosentino, 2011). This result is similar to the median internal consistency of .77 – with a range from .71 to .90 – observed for a VIA-IS German adaptation (Ruch et al., 2010). It should be highlighted that Cronbach alpha is not necessarily a measure of the dimensionality of participant responses nor indicates the degree to which we are measuring a single construct. However, it is considered an indicator of how participants’ responses are associated —i.e., covary— (Helms, Henze, Sass, & Mifsud, 2006). Furthermore, no internal consistency indexes can be calculated for a given strength because the SCI consisted of one item per strength. Consequently, test-retest correlations, which represent the temporal stability of scores, are relevant for assessing the reliability of the SCI (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003). The median test-retest correlations for 3 weeks for the SCI was r = .79, ranging from .72 to .92, in a sample of 123 individuals (70 women), with a mean age of 37.8 years, SD = 15.6 (Cosentino, 2011). These indexes of temporal stability are similar to the test-retest correlations observed for the VIA-IS German adaptation: Mdn = .78, ranging from .69 to .87 (Ruch et al., 2010).

2.3.2 Evidence of Validity

2.3.2.1 Relationships Between the Strength of Character Inventory and the Satisfaction with Life Scale

It was proposed that, by definition, the character strengths contribute to fulfillment, satisfaction and happiness in a broad sense (Park et al., 2004; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Park et al. have found that all character strengths were directly related to life satisfaction, even after controlling for sex, age, and citizenship (nationality), with a Mdn of r = .25, with a range from .05 to .53. Similarly, Cosentino (2011) found that all strengths of character (except humility) as measured by the SCI are directly associated with life satisfaction, even after controlling for age and sex, Mdn of r = .25, ranging from .13 to .57. Moreover, both studies have the same seven character strengths with the highest partial correlations with life satisfaction: gratitude, curiosity, vitality, hope, persistence, love and perspective.

2.3.2.2 Relationships Between the Strength of Character Inventory with the Big Five Inventory

Peterson and Seligman (2004) have posited that it is very important to consider the relationships between the VIA character classification and the Big Five personality model – developed from the convergence of words related to the personal characteristics (Goldberg, 1993) – because it makes meaningful the VIA classification. Using the SCI, Cosentino (2011) study character strengths – presented between dashes – associated with the Big Five factors. He found positive relationships with at least medium effect sizes between: (a) all the associations of character strengths with conscientiousness —persistence, zest, self-regulation, hope, honesty—, agreeableness —kindness, fairness, forgiveness, prudence—and emotional stability —hope—; (b) almost all the associations with openness to experience —creativity, love of learning, and appreciation of beauty and excellence—; and (c) most of the associations with extraversion. —social intelligence, humor and bravery—. The associations found between character strengths measured with the SCI and the factors of the BFI are similar to the empirical results of the relationship between the character strengths of VIA classification and the Big Five factors showed by Peterson and Park (2004), and the results found by MacDonald et al. (2008).

2.3.2.3 Relationships Between the Strength of Character Inventory and the Social Desirability Scale

When individuals describe themselves with culturally appropriate and acceptable —i.e., socially desirable— characteristics, as the strengths of character, some researchers conjecture a possible relationship with the social desirability construct (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2008a; Crowne & Marlowe, 1964). Peterson and Seligman (2004) have argued that the character strengths are socially desirable. However, these authors have surprisingly sustained that character strengths do not correlate with social desirability. It seems more reasonable to assume that if, by definition, the character strengths are socially desirable; consequently the strengths should tend, in general, to show associations with social desirability. This conclusion can be supported by the results of two studies that showed that more than the half of the character traits are associated with social desirability (Macdonald et al., 2008; Sarros & Cooper, 2006), and an investigation with adolescents that founded similar results (Osin, 2009). In relation to the SCI, all strengths were founded positively associated (Mdn of r = .26, in the range from .11 to .39) with social desirability measured with an Argentinean adaptation of Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale in a sample of 781 individuals from the Argentina general population (Cosentino, 2011).

2.3.3 Convergence with Objective Assessment

Cosentino (2011) studied the relationship between self-report character strength scores and the scores of an objective assessment on this topic. A total of 178 people (99 women) – with a mean age of 32.9 years (SD = 11.6) – filled out the SCI, while 178 participants set as observers (95 women) – with a mean age of 32.5 years (SD = 11.3) – filled out the SCI in reporting format. Observers had a social bond with the observed participants, they mostly were couples, friends, or family and had known each other for a mean of 13 years (SD = 12.4). Correlations between the SCI scores and the SCI informant-form scores showed a mean of r = .49, ranging from .35 (integrity) to .75 (spirituality). These coefficients are similar to, and somewhat higher than, those found by Ruch et al. (2010), which showed a median correlation of .40 between the VIA-IS scores and the peer format VIA-IS scores. In particular, both studies agree on the strongest —spirituality and love of learning— and weakest —honesty— score convergences.

3 Character Strengths in Argentina Population

3.1 Character Strengths in General Population of Argentina

Samples from different countries have shown sex and age differences in character strengths (e.g., Linley et al., 2007; Ruch et al., 2010). Therefore, a study was conducted to determine sex and age differences in strengths of character with Argentinean population.

Firstly, I studied the relationship between character strengths and age, including sex as a covariate (Cosentino, 2011). In general, results showed that the more the age, the greater the character strength presence. More specifically, age is associated with 12 strengths with small-to-medium correlations. There was a positive association between age and character strengths of prudence, spirituality, self-regulation, honesty, appreciation, humility, fairness, gratitude, perspective, persistence and forgiveness; while negative association were found for age and humor. Age also showed positive associations with the character strengths of zest, open-mindedness, and hope, with less than small effect sizes.

I also analyzed the differences in character strengths by sex, using age as a covariate (Cosentino, 2011). In general, it was observed sex differences in strengths of character, and specifically, it was observed that women scored higher than men did on character strengths as follows: firstly, on spirituality, forgiveness, kindness, honesty, and love with small-to-medium effect sizes; secondly, on gratitude, humility, love of learning, and fairness with less than small effect sizes. However, in creativity, men scored higher than women with a small-to-medium effect size. Results of a descriptive discriminant analysis showed that women clearly present higher levels of spirituality, forgiveness, kindness, and honesty than men, but also lower levels of creativity than their counterparts. These results are consistent with the character strengths that shown higher effect sizes in the univariate analyses.

3.2 Comparison of Character Strengths Between Civilian and Military Population of Argentina

Military population is a very interesting group to be studied from the perspective of positive psychology. The Army could be considered as a positive institution because this institution selects individuals with positive traits or stimulates the development of positive traits among its members. Actually, the character is an issue of particular importance in the military field. Firstly, the military doctrine (Ejército Argentino, 1990) and military individuals (Casullo & Castro Solano, 2003) propose that military leaders must have characteristics that are similar to some of the character strengths of the Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) classification. Secondly, students’ character traits are assessed in the military academy. In contrast to the usual civilian university, the military academy assign a grade for personal characteristics (or positive traits) that is included into the global assessment of cadets’ performance, having a significant role for cadets’ stay at the military college (Cosentino, 2011).

In view of the importance of positive personal traits for the military area, Cosentino (2011) hypothesized that (a) military college students present higher positive traits than civilian college students; (b) military students close to the course finalization at the military college (“seniors”) differ in their positive traits from cadets who recently enter to the college (“freshman”); and (c) positive traits are associated with performance at the military academy – mainly focusing on the last year of courses – because military students who exhibit higher performance had the best adaptation to the entire educational program.

Cosentino (2011) compared the VIA character strengths between military and civilian samples, balanced by age, sex (male), and training (all study years were proportionally present). Results of univariate analyses with social desirability as a covariate are shown in Table 6.3. A descriptive discriminant analysis showed that spirituality clearly maximizes the separation between military and civilian student samples.

The evident higher presence of spirituality in military students in comparison to civilian students (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012) is consistent with results from a study on values conducted in the same military academy. This study showed that military individuals more strongly agree to tradition and conformity type of values from the Schwartz’s theory than civilian individuals (Castro Solano & Nader, 2006; see Schwartz, 2006, for a summary of his theory). Consistently, results of a meta-analysis of studies from 15 countries of monotheistic religious traditions, such as Argentina (Mallimaci, Esquivel, & Irrazábal, 2008), showed that religious individuals mainly agree with that same types of values (Saroglou, Delpierre, & Dernelle, 2004). Finally, the higher presence of spirituality in military students in comparison to civilian students is also compatible with the military doctrine, as spirituality is considered an important characteristic to ensure an effective leadership and a crucial aspect for leadership at critical moments (Ejército Argentino, 1990).

Both, the results of the study conducted in Argentina and the results of Matthews et al. (2006) research in the U.S. consistently show that military students score higher than civilian students in several character strengths. Despite the differences between the Argentina military academy (Castro Solano, 2005) and the West Point academy (Alberts, 2009; Matthews, 2008), military doctrines from both Argentina and the U.S. support moral virtues for the military leadership (Department of the Army, 1999; Ejército Argentino, 1990; Matthews et al., 2006). Thus, it seems that moral virtues for leadership are the key factors underlying the similar results observed in both studies when comparing military and civilian populations.

3.3 Comparison of Character Strengths Among Military Students

Because positive traits are so intensely valued by military academies and military students generally present higher character strengths in comparison to civilian students, some question arises: Do individuals with high positive traits tend to enter to military academies or do they develop their character strengths at the military academy? I tried to answer this question by comparing character strengths between freshman and senior military students. It was hypothesized that differences in positive traits between freshmen and seniors will be interpreted as a modification of positive traits due to their stay at the military academy.

A sample of male cadets was selected from the first and the last year of the course (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Results from univariate analyses, including social desirability as a covariate, showed that seniors cadets score lower on the character strengths of kindness and teamwork, and score higher on forgiveness than freshmen. More profoundly, a descriptive discriminant analysis showed that seniors clearly present lower levels of kindness and teamwork than freshmen. This difference between freshman and senior military students is consistent with the implicit leadership theories (TILs) of military students before and during their role as a leader at the military academy (Castro Solano, 2006; Castro Solano & Nader, 2008). The TILs of military cadets who had a role as a leader were less cooperative and more egocentric. Consequently, it was hypothesized that cadets have a mental image of a leader that is consistent with the traits they actually have as military leaders.

Due to, firstly, military students score in general higher on character strengths when compared to civilian students, and secondly, the differences in character strengths between freshman and senior military students are not present when military and civilian students are compared, I hypothesized that people with higher positive traits tend to enter in the military academy, having a subsequent adjustment of these character strengths while staying at the military organization (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Additionally, this hypothesis is consistent with the idea of character strengths as stable and malleable aspects (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

4 Character Strengths and Academic Performance

For decades, performance was a widely studied variable in psychology. Predictors of academic performance are classified as intellectual factors and non-intellectual factors (Castro Solano, 2005). Analytical intelligence was traditionally considered as a performance predictor in educational military programs, but more recently other variables were included into the network of performance predictors. Several studies have found that non-intellectual factors predict the performance of military and college students. Specifically, it was found that personality, practical intelligence, and motivational characteristics are predictors of military performance of Argentinean cadets (Benatuil & Castro Solano, 2007; Castro Solano, 2005; Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001; Castro Solano & Fernández Liporace, 2005).

The positive character traits can be considered as non-intellectual factors. Based on the VIA classification of character (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), a study that used self-reported mean for grades of college students showed that 16 character strengths were associated with academic performance in civilian population (Lounsbury et al., 2009). Moreover, an article reported that perseverance, prudence, and love were associated to higher grades in students (Peterson & Park, 2006). Although there are no many articles on the relationship between VIA character strengths and military performance, one article specifically reported that the character strength of love predicted accomplishments as a leader in U.S. military academy cadets (Peterson & Park).

Cosentino and Castro Solano (2012) studied the relationship between VIA character strengths and objective performance, i.e., grades obtained from the records of an Argentinean military college. They considered two types of performance: academic (similar to academic performance for students in civilian colleges) and military (specific for military students). In order to evaluate the military performance, an averaged score was calculated with (a) the grades assigned by officers who assess several aspects of cadets performance through observation of indicators —such as behavior, military personality, field exercises, ability to lead, among others—, and (b) the grades assigned by military professors who teach theoretical issues on specific military subjects —such as tactics, explosives, among others—.

To study whether the VIA character strengths would predict military and academic performance, these relationships were analyzed in freshman and in senior military student samples, respectively (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Results of these analyses showed that, in general, the strengths of character are associated to performance. These observed results support once again a general hypothesis that states that non-intellectual factors are associated to performance and a particular hypothesis that maintain specifically this association for college military population. However, the results were mixed: simple correlation coefficients showed that both academic and military performance (a) are positively associated with the character strengths of love of learning and leadership, while are negatively associated with the character strength of fairness in freshmen, and (b) are positively associated with the character strength of persistence in senior students.

Another procedure was conducted to study the relationships between character strengths and performances in military students. Cadets with grades above the 70th percentile (high performance) and cadets with grades below the 30th percentile (low performance) were selected to constitute high and low performance groups for the first and for the last year samples. This method was used for both academic and military performance (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012).

A descriptive discriminant analysis showed that, in general, the character strength of fairness makes a consistent contribution to the separation between groups of high and low performance in both academic and military performance, in first year military sample (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Particularly, the results showed that (a) for academic performance, high performance group score lower in fairness but higher in love of learning than the low performance group; and (b) for military performance, the high performance group score lower in fairness than the low performance group.

The pattern of results for the relationships between the character strengths and both academic and military performance for the last year sample is clearly different from the pattern of results for the first year sample (Cosentino, 2011; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Both academic and military performance and the character strength of persistence reliably separates between the high and the low performance groups in the last year courses. That is, cadets with high performance report higher character strength of persistence in comparison to cadets with low performance. I assumed that seniors with higher performance not only show the best adaptation to the military academy but also show the best closeness with the ideal military leader that the military institution supports.

5 Summary

The SCI is a short self-report consisted of 24 items to measure the VIA classification of character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), which items reflects a wide range of manifestations of the character strengths in thoughts, feelings and behaviors. A short instrument for measuring character strengths meets the needs of many researchers who are looking for quicker assessments that imply lower levels of fatigue for individuals.

The comparison in character strengths between military and civilian students showed that military students generally have higher levels of character strengths than civilian students. This difference appears to reflect the emphasis that military doctrine places on the positive traits for their future military leaders.

Although the character strengths are not defined on the basis of outcome variables (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), it is interesting to know what and how positive traits are related to the outcome variables because, among other reasons, they could be part of a network of predictor variables. Empirical studies show that character strengths are related to academic and military performance of military students in Argentina. An interesting finding was that freshman and senior cadets’ performance at the military academy in Argentina are mixed: character strengths are both positively and negatively related to performance. Consequently, these mixed results indicate that is necessary to avoid the tendency to overgeneralize across samples. Instead of assuming that anything positive is always positive, it could be better to assume that what is considered as a strength in a particular environment could function as a weakness in another, and vice versa (Aspinwall and Staudinger, 2003). In other words, the association between the character strengths and the outcome variables could vary across populations and contexts.

References

Alberts, H. R. (2009, August 24). America’s best college. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0824/colleges-09-education-west-point-america-best-college.html

Aspinwall, L. G., & Staudinger, U. M. (2003). A psychology of human strengths: Some central issues of an emerging field. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 9–22). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bäccman, C., & Carlstedt, B. (2010). A construct validation of a profession-focused personality questionnaire (PQ) versus the FFPI and the SIMP. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 136–142. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000019.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226.

Benatuil, D., & Castro Solano, A. (2007). La inteligencia práctica como predictor del rendimiento de cadetes militares [Practical intelligence as achievement predictor in army students]. Anuario de Psicología (Spain), 38(2), 305–320.

Burisch, M. (1984). Approaches to personality inventory construction: A comparison of merits. American Psychologist, 39(3), 214–227. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.39.3.214.

Castro Solano, A. (2005). Técnicas de evaluación psicológica en los ámbitos militares [Psychological assessment techniques in the military area]. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós.

Castro Solano, A. (2006). Teorías implícitas del liderazgo, contexto y capacidad de conducción [Implicit leadership theories, context and leadership position]. Anales de Psicología, 22(1), 89–97.

Castro Solano, A., & Casullo, M. M. (2001). Rasgos de personalidad, bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en adolescentes argentinos [Personality traits, psychological well-being, and academic achievement of Argentine adolescents]. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 18(1), 65–85.

Castro Solano, A., & Fernandez Liporace, M. (2005). Predictores para la selección de cadetes en instituciones militares [Predictors for the selection of cadets in military institutions.]. Psykhe: Revista de La Escuela de Psicología, 14(1), 17–30.

Castro Solano, A., & Nader, M. (2006). La evaluación de los valores humanos con el Portrait Values Questionnaire de Schwartz [Human values assessment with Schwartz’s Portrait Values Questionnaire]. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 23(2), 155–174.

Castro Solano, A., & Nader, M. (2008). Análisis del cambio en las teorías implícitas del liderazgo como producto del entrenamiento en las habilidades para liderar en cadetes militares [Analysis of the change in the implicit theories of leadership as a product of training in skills to lead in military cadets]. Boletín de Psicología (Spain), 94, 57–68.

Casullo, M. M., & Castro Solano, A. (2003). Concepciones de civiles y militares argentinos sobre el liderazgo [Conceptions of leadership among military and civil Argentines]. Boletín de Psicología (Spain), 78, 63–79.

Cattell, R. B. (1943). The description of personality: Basic traits resolved into clusters. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 38(4), 476–506. doi:10.1037/h0054116.

Cattell, R. B. (1947). Confirmation and clarification of primary personality factors. Psychometrika, 12, 197–220. doi:10.1007/BF02289253.

Cawley, M. J., III, Martin, J. E., & Johnson, J. A. (2000). A virtues approach to personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 997–1013. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00207-X.

Cosentino, A. C. (2011). Fortalezas del carácter en militares argentinos [Character strengths in Argentinean soldiers]. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universidad de Palermo, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Cosentino, A. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2008a). Adaptación y validación argentina de la Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale [Argentinian adaptation and validation of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale]. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 25(2), 197–216.

Cosentino, A. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2008b). Inventario de virtudes y fortalezas [Virtues and strengths inventory]. Unpublished manuscript.

Cosentino, A. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2012). Character strengths: A study of Argentinean soldiers. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 199–215. doi:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37310.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1964). The approval motive: Studies in evaluative dependence. New York: Wiley.

Department of the Army. (1999). Army leadership: Be, know, do (Field Manual No. 22-10.). Washington, DC: Author

Ejército Argentino. (1990). Manual del Ejercicio del Mando [Command manual MFP-51-13. (N. c.)]. Argentina: Author.

Fiske, D. W. (1949). Consistency of the factorial structures of personality ratings from different sources. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 44(3), 329–344. doi:10.1037/h0057198.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48(1), 26–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

Harlan, E., & Clark, L. A. (1999). Short forms of the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP) for self- and collateral ratings: Development, reliability, and validity. Assessment, 6(2), 131–145. doi:10.1177/107319119900600203.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511.

Helms, J. E., Henze, K. T., Sass, T. L., & Mifsud, V. A. (2006). Treating Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients as data in counseling research. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 630–660. doi:10.1177/0011000006288308.

Herzog, T. K., Hughes, F. M., & Jordan, M. (2010). What is conscious in perceived attachment? Evidence from global and specific relationship representations. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 283–303. doi:10.1177/0265407509347303.

Levy, K. N., & Kelly, K. M. (2010). Sex differences in jealousy: A contribution from attachment theory. Psychological Science, 21(2), 168–173. doi:10.1177/0956797609357708.

Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., Peterson, C., et al. (2007). Character strengths in the United Kingdom: The VIA inventory of strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(2), 341–351. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.004.

Lounsbury, J. W., Fisher, L. A., Levy, J. J., & Welsh, D. P. (2009). An investigation of character strengths in relation to the academic success of college students. Individual Differences Research, 7(1), 52–69.

Macdonald, C., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2008). Values in action scale and the Big 5: An empirical indication of structure. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 787–799. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.10.003.

Mallimaci, F., Esquivel, J. C., & Irrazábal, G. (2008). Primera encuesta sobre creencias y actitudes religiosas en Argentina [First survey on religious beliefs and attitudes in Argentina]. Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones Laborales-Programa de Investigaciones Económicas sobre Tecnología, Trabajo y Empleo del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas. Argentina: Buenos Aires. Retrieved from http://www.ceil-piette.gov.ar/areasinv/religion/relproy/1encrel.pdf

Matthews, M. D. (2008). Positive psychology: Adaptation, leadership, and performance in exceptional circumstances. In P. A. Hancock & J. L. Szalma (Eds.), Performance under stress (pp. 163–180). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Matthews, M. D., Eid, J., Kelly, D., Bailey, J. K. S., & Peterson, C. (2006). Character strengths and virtues of developing military leaders: An international comparison. Military Psychology, 18(Suppl), S57–S68. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1803s_5.

McCullough, M. E., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Classical source of human strength: Revisiting an old home and building a new one. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 1–10. doi:10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.1.

Nicholson, I. A. M. (1998). Gordon Allport, character, and the “culture of personality”, 1897–1937. History of Psychology, 1(1), 52–68. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.1.1.52.

Norman, W. T. (1963). Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality ratings. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(6), 574–583. doi:10.1037/h0040291.

Norman, W. T., & Goldberg, L. R. (1966). Raters, ratees, and randomness in personality structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(6), 681–691. doi:10.1037/h0024002.

Osin, E. N. (2009). Social desirability in positive psychology: Bias or desirable sociality? In T. Freire (Ed.), Understanding positive life: Research and practice on positive psychology (pp. 421–442). Lisboa, Portugal: Climepsi Editores.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748.

Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). New York: Guilford Press.

Peterson, C., & Park, N. (2004). Classification and measurement of character strengths: Implications for practice. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 433–446). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Peterson, C., & Park, N. (2006). Character strengths in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1149–1154. doi:10.1002/job.398.

Peterson, C., Park, N., Pole, N., D’Andrea, W., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Strengths of character and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(2), 214–217. doi:10.1002/jts.20332.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Greater strengths of character and recovery from illness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 17–26. doi:10.1080/17439760500372739.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. XIV). New York: Oxford University Press.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 151–161. doi:10.1177/0146167201272002.

Ruch, W., Proyer, R. T., Harzer, C., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2010). Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS): Adaptation and validation of the German version and the development of a peer-rating form. Journal of Individual Differences, 31(3), 138–149. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000022.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V., & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(4), 721–734. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.10.005.

Sarros, J. C., & Cooper, B. K. (2006). Building character: A leadership essential. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(1), 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10869-005-9020-3.

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Les valeurs de base de la personne: Théorie, mesures et applications [Basic human values: Theory, methods and applications]. Revue Francaise De Sociologie, 47(4), 929–968.

Steger, M. F., Hicks, B. M., Kashdan, T. B., Krueger, R. F., & Bouchard, T. J., Jr. (2007). Genetic and environmental influences on the positive traits of the values in action classification, and biometric covariance with normal personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(3), 524–539. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.06.002.

Stroud, C. B., Durbin, C. E., Saigal, S. D., & Knobloch-Fedders, L. M. (2010). Normal and abnormal personality traits are associated with marital satisfaction for both men and women: An actor–partner interdependence model analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 466–477. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.011.

Tupes, E. C. (1957). Relationship between behavior trait ratings by peers and later officer performance of USAF officer candidate school graduates (Research Report AFPTRC-TN-57-125. ASTIA Document No. AD 134 257). San Antonio, TX: Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center.

Tupes, E. C., & Christal, R. C. (1958). Stability of personality trait rating factors obtained under diverse conditions (Technical Note WADC-TN-58-61. ASTIA Document No. AD-151 041). San Antonio, TX: Personnel Laboratory, Wright Air Development Center.

Tupes, E. C., & Christal, R. E. (1961). Recurrent personality factors based on trait ratings (Technical Report No. ASD-TR-61-97). San Antonio, TX: Personnel Laboratory, Aeronautical Systems Division. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycextra/531292008-001

Want, S. C., Vickers, K., & Amos, J. (2009). The influence of television programs on appearance satisfaction: Making and mitigating social comparisons to “Friends”. Sex Roles, 60(9–10), 642–655. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9563-7.

Wilt, J., Schalet, B., & Durbin, C. E. (2010). SNAP trait profiles as valid indicators of personality pathology in a non-clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(6), 742–746. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.020.

Woods, S. A., & Hampson, S. E. (2005). Measuring the Big Five with single items using a bipolar response scale. European Journal of Personality, 19(5), 373–390. doi:10.1002/per.542.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cosentino, A.C. (2014). Character Strengths: Measurement and Studies in Argentina with Military and General Population Samples. In: Castro Solano, A. (eds) Positive Psychology in Latin America. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology, vol 10. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9034-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9035-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)