Abstract

This chapter addresses the study of cultural competences involved in the successful adaptation of a particular group of migrants: international students. Cultural competences are skills that people display when facing cultural diversity and have been found to predict job performance and academic achievement of those who have to interact in different contexts other than their own. This chapter aims to respond three questions that students consider when studying abroad: ‘What should I do to have a successful life?’, ‘How prepared are members of the host culture to receive me?’, and, ‘Who are the most successful international students?’ The first segment introduces the role of acculturative strategies of Latin American international students in Argentina in order to predict psychological adjustment (life satisfaction) and sociocultural adaptation. The second section presents local students perceptions and attitudes towards international peers and multiculturalism. The last section describes sociodemographic, cultural and psychological predictors of psychological adjustment, sociocultural adaptation and academic achievement, as well as the relationship between character strengths and cultural and academic adjustment. Finally, the role of cultural competences sensitivity and cultural intelligences as cultural competences is explained. Results demonstrate the importance of cultural variables in positive adaption to culture.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

What happens to people who were born and educated in a particular cultural context when they decide to live in a culture different from their own? If culture has a strong influence on human behavior, do people continue to behave in the same way or do they change their repertoire of actions to better fit in the new environment? What factors make some people to succeed and others to fail in this endeavor? This chapter addresses the study of the variables involved in the successful adaptation of a particular group of migrants: international students. From the Positive Psychology perspective, this chapter will focus on the study of those resilient individuals. That is, those people who possess certain type of strengths that allow them to maintain their psychological well-being in a cultural context different from their own and that might at times be adverse for them.

Recent statistics show that by 2010 there were approximately 214 million migrants worldwide. This number represents 3 % of the world’s population. Globalization has facilitated contact between members of different cultures, but at the same time, has also caused the collision between different systems of values, beliefs and practices, which in many cases, generates confused and distressful situations for individuals (Furnham & Bochner, 1986).

Currently, the number of international students in the world is the largest in modern history. Foreign students have been characterized as people who voluntary and temporary reside in a country other than their own, with the purpose of participating in an educational exchange and the intention of returning to their country once their trip objective is achieved (Lin & Yi, 1997). International students have been called sojourners (Church, 1982). That is, people who migrate from one cultural context to another, for a relatively long period of time – from 6 months to 5 years – in order to perform a particular task. Sojourners generally plan their trip and their return, and their stays are of moderate length (Ward, 1999; Ward, Bochner & Furnham, 2001). This category also includes business people, students, technical experts, military personnel and diplomats.

Universities in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Trade Development (OECD) countries receive approximately 1.5 million international students. Among them, the United States of America lead the group, followed by England, Germany, France and Australia (Rodríguez Gómez, 2005). Latin America receives a lower number of international students compared to these countries. Brazil, Mexico and Argentina have the highest percentage of foreign students in the region.

Since 2000, Argentina has begun to receive a significant number of international students. These students are mainly from other Latin-American countries, who are attracted by the language, the favorable economic conditions and the prestige of Argentinean universities’ level. Currently, international students represent 1.6 % of the university population, reaching 24,000 students. In 2006 foreigners represented only 10,000 students, but it has since doubled in the next 2 years. This data places Argentina in the fourth host country in the Americas after the United States, Canada and Uruguay (OEI), receiving mainly Latin-American students and to a lesser extent, Anglo-Saxon students (Filmus, 2007).

In summary, the migratory phenomenon has significantly increased in recent decades with this trend tipped to increase further. University students’ migration is also an important phenomenon, particularly growing in Argentina. On the one side, migration can lead to a series of difficulties as a result of the cultural dialogue between countries with different traditions and values. On the other side, it can be a source of possibilities, both for individuals and societies (Baubock, Heller, & Zolberg, 1996). Taking this into account, Psychology has been contributing to make this process as positive as possible and to diminish potential negative effects.

Acculturation is the primary psychological phenomenon that international students must contend with. This process implies the psychological and cultural changes experienced as a result of intercultural contact (Berry, 2003). Cultural changes include modifications in customs, and economic and political lives of those involved in contact groups. Psychological changes – psychological acculturation – involve changes in attitudes toward acculturation process, toward ones’ identity and behaviors toward the host culture (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006a, 2006b). In this way, acculturation implies adaptation.

Adaptation can be either psychological or sociocultural (Searle & Ward, 1990; Ward, 2004). While psychological adaptation is related to the well-being experienced as a result of cultural contact, sociocultural adaptation involves the absorption of social skills necessary to adequately function in a complex cultural environment (Ward et al., 2001).

Several studies have aimed to identify predictors of adaptation. Literature has mentioned perceived social support, personality traits and life events as the major predictors of psychological adjustment. In relation to sociocultural adaptation – which involves successful resolution of practical problems in the interaction with members of the host culture – the main factors found to explain it were: cultural distance, cultural knowledge, frequency of contact with members of the host culture and perceived discrimination (Ward, 2004; Ward & Kennedy, 1994). In a recent review of sociocultural adaptation’s predictors, Zlobina, Basabe, Paez, and Furnham (2008) added to this list, migrants’ educational level, length of stay, age and gender.

If adaptation is not reached, migrants might experience characteristics of acculturative stress. This stress occurs when people experience adverse physical and emotional reactions as a result of the complex process of adjustment to an unfamiliar cultural context. Acculturative stress particularly arises from the stress experienced when contrasting values and customs from their own culture with those from the host cultural context (Berry, 2005; Gil, Vega, & Dimas, 1994; Rodriguez, Myers, Bingham, Flores & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002; Williams & Berry, 1991). As some authors have concluded (Ward & Kennedy, 1994), studying abroad might be one of the most stressful events in peoples’ lives.

Given that the number of international students is growing in Argentina, a series of research studies were designed in order to study international students’ acculturation process, analyzing variables involved in the effective cultural and psychological adaptation. These studies were conducted during 2008–2010 and aimed to respond to three basic questions that students might consider before beginning their studies abroad: What should I do to have a successful life?; How prepared are members of the host culture to receive me?, and; Who are the most successful international students?

2 What Should I Do to Have a Successful Acculturation?

Until the 1960s, acculturation was believed to be a unilinear process in which immigrants would gradually incorporate aspects of the host culture while losing some aspects of their cultural background (Gordon, 1964). This process was completed once the new culture had been absorbed. During mid-1970s, Berry and his colleagues conducted a pivotal study with a group of minority immigrants, which resulted in an acculturation model that has had a broad international impact, both in the United States and Europe (Berry, 1997). This classic model proposes two separate dimensions of the process of acculturation:

-

1.

Immigrants consider their cultural identity and their customs valuable enough to keep them in the host society (maintenance)

-

2.

Relationships with people or groups of the host society are considered valuable enough to look for and promote them (participation).

These two dimensions create different acculturation strategies, depending on how people face their process. Thus, migrants have four possible responses:

Integration | Migrants try to keep their cultural heritage and also maintain contact with the dominant cultural group |

Assimilation | Individuals do not retain their original culture and attempt to maintain contact only with members of the dominant group |

Separation | Migrants are able to maintain their original culture, avoiding interaction with members of the dominant group or other groups |

Marginalization | Individuals are not interested or able to maintain their original culture but are also unlikely to come into contact with members of the host culture. |

Overall, studies conducted with Berry’s model of acculturation strategies concluded that the integration strategy is associated with both better sociocultural and psychological adaptation, while the separation strategy predicts a poorer adjustment (Zlobina et al., 2008).

What happens particularly in Argentina? In order to assess the acculturation strategies employed by a group of international students who had migrated to complete their university studies in this country, a four-item short questionnaire was designed based on Berry’s two-dimensional model (1997; Castro Solano, 2011). This scale was administered to foreign and local students to gather information and cross-validate the results. Two samples of undergraduate students were included in the study (125 international students and 121 Argentinean students from various courses and schools). The effectiveness of the implemented strategies was analyzed by exploring sociocultural and psychological adaptation, academic adjustment, immigrants’ perceived discrimination and life satisfaction.

Firstly, results indicate that Integration was the preferred acculturation strategy while Marginalization was the least chosen one. As shown in Fig. 5.1, perceptions of both, individuals who are in the process of acculturation and members of the host culture agreed on this point. Acculturation is achieved when aspects of both cultures are taken into account, preserving valued aspects of one’s cultural identity and, at the same time, participating in an exchange with the host culture. This might be the reason why integration has been found to be the most commonly chosen strategy, while marginalization, which implies the rejection of both host culture and culture of origin, has been found to be the least preferred strategy.

Secondly, results from this study also indicate that Integration is the strategy that brings better adaptive outcomes. International students who adopted an integrative style were those who also perceived greater life satisfaction and better adjustment to the academic life (Table 5.1). By contrast, foreign students who chose the Separation strategy, maintaining only aspects of their cultural identity and avoiding contact with the host culture, were those who reported lower levels of adjustment to the country lifestyle – sociocultural adaptation – and perceived more discrimination.

In terms of students’ perceptions of immigrants preferred acculturation strategies, both groups, international and local students, tend to agree on their observations. However, there are some nuances in relation to their perceptions of the acculturation strategies’ implementation. Results showed that members of the host culture believe that international students tend to assimilate more or separate more from the new culture than they actually do. However, this pattern of responses observed was similar and consistent in both international and local students. In relation to foreigners’ observations about what Argentineans perceive, there were also similar patterns of responses. These findings indicate that preferences for integration, as an acculturative strategy, is accepted and also encouraged by the host culture, as it is believed to result in a better sociocultural adaptation in the long term (Berry, 1997; Berry et al., 2006a, 2006b).

One of the main contributions of this study is to add empirical validation to the theoretical model used. To date, reviewed studies using Berry’s model have generally include populations from different cultural characteristics, with a larger cultural distance, while the research conducted in Argentina consisted mainly of a Latin sample of students acculturating to a country that also has a Latin background.

Moreover, there are also few studies that have analyzed perceptions of both groups involved in the acculturation process, immigrants and members of the host society (Bourhis, Moise, Perreault, & Senecal, 1997; Ward, Larissa Kus, & Masgoret, 2008). As sojourners are not that free to choose any acculturation strategy, as they need to be accepted by the local group as well (Berry, 2003). Literature highlights the importance of taking into consideration both perspectives – migrants and locals – when studying this topic. Particularly, it is important to consider immigrants’ perceived discrimination as this variable has shown to be a pivotal moderator in the acculturation process.

It should be taken into consideration that, in the described study, perceptions of both groups involved in the acculturation process were similar. These findings might be explained by the characteristics of the sample. This group of international students had been attracted to conduct their university studies in Argentina by the favorable conditions of the host country. It might be possible that if they have belonged to more disadvantaged groups and the reasons for migration were related to improving their economic conditions, perceptions of both groups would have tended to be less similar. Therefore, intercultural relations problems might have arose and adaptation to the country might have been poorer (Bourhis et al., 1997).

3 How Prepared Are Members of the Host Culture to Receive Me?

Most research studies that analyzed relationships between international students and their local counterparts have been done from migrant students’ point of view. They mainly have considered quality and frequency of contact, friendship networks and social support networks. Findings indicate that interaction between immigrants and members of the host culture is relatively low. Although international students expect greater frequency of contact with local students they are not always successful in this endeavour (Holmes, 2005; Ward, Berno, & Kennedy, 2000) and this has been traditionally a concern of educators and institutions’ managers (Ellingboe, 1998; Smith, 1998). Although frequent interaction between international and local students has been associated with higher levels of psychological well-being and better academic performance for international students which in turn, lead to a more positive adaptation, few studies have explored both foreigners’ and hosts’ points of view combined.

Local students’ perceptions about their international peers vary according to the cultural group or country they belong to. Overall, research studies found a more positive attitude toward students with similar cultural characteristics (Ward & Leong, 2006). For example, it was found that students from New Zealand were more likely to positively perceive their counterparts from Australia and England than their peers from South Africa (Ward & Masgoret, 2005b). Moreover, it was also demonstrated that, based on sojourners’ English pronunciation, American students had a more positive attitude toward European students than toward their Chinese and Mexican counterparts. The number of international students enrolled in a class is also an important moderator of local students’ perception. Research studies have shown that the higher the rate of international students in a classroom, the more negative attitudes and the more frequent discriminatory behavior they received from their classmates (Ward & Masgoret, 2005a).

Members of the host culture’s perceptions of their counterparts are an important predictor of effective intercultural contact. Although the role of international students’ negative stereotypes has been traditionally emphasized, evidence comes from anecdotal rather than empirical well-designed research. A few studies on perceptions of foreign students indicate that, in general, attitudes toward these students are moderately positive (Haddock, Zanna, & Esses, 1994; Spencer-Rodgers, 2001; Spencer-Rodgers & McGovern, 2002; Ward & Masgoret, 2005a). However, it is interesting to mention that some research studies found that international students consider their local counterparts as uninformed about and not interested in their cultures (Mills, 1997; Smart, Volet, & Ang, 2000; Yang, Teraoka, Eichenfield, & Audas, 1994).

With these findings in mind, a study was designed with the purpose of exploring local students’ perceptions and attitudes toward their international peers. In order to undertake this study, 182 psychology students from a university with a high proportion of international students (25 %) were recruited. Participants were asked to respond to a questionnaire about their experience with foreign students. Results showed that 40 % of the sample had been in contact with one to five international students while the remaining 60 % had been acquainted with 6–10 students. These results showed that this sample of local students had high frequency of interaction with their foreign counterparts.

The instrument designed for the study consisted of four questions to be answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Table 5.2 presents means obtained for each category after assigning a score from 1 to 5 to each item. These data show that host students think that international students’ rate is high both nationally and at the university where they are currently studying. Frequency of contact with foreigners is also considered with high levels and the quality of this contact is evaluated as positive or very positive.

Secondly, local students’ attitudes toward international students were assessed both in general and for each ethnic group in particular (Table 5.3). Overall, a favorable attitude toward foreign university students was reported. In particular, South-American students are those who received the higher score on this variable, North-American students received intermediate scores, and Asians and Africans students received the lowest scores.

Results showed that host students present a moderately positive attitude toward international students in general. However, findings indicate that students who come from culturally distant countries are perceived with less positive attitudes than students from closer nations in terms of customs and values. These results are consistent with studies about acculturation process that have found a negative relationship between positive attitudes and cultural distance: the greater the cultural distance the more difficult the acculturation process (Berry, 1997; Bochner, 1981; Furnham & Alibhai, 1985; Ward & Masgoret, 2004). Similarly, and consistent with literature on perceptions of international students (Ward, 2006), foreign students are positively perceived in the Argentinean study. These findings are possibly explained by the frequency of contact and constant interchange that participants had with their international peers. As an extensive meta-analysis of the contact hypothesis (Amir, 1969) indicates, those individuals who frequently interact with foreigners, and also have a positive contact experience, tend to have more positive perceptions about migrants (Pettigrew & Troop, 2000).

Thirdly, in an attempted to verify the theoretical model for the prediction of contact with international students, a study was designed based on Masgoret and Ward’s proposal, exploring cultural variables as factors (Ward, 2006). This model posits that perceptions of threat – real and symbolic – govern attitudes toward foreigners (Stephan & Stephan, 2000). These attitudes are also influenced by more distal variables such as intergroup anxiety and attitudes toward multiculturalism. The stronger the multicultural ideology held by the host culture, the greater the acceptance of immigrants and therefore, the more positive the attitudes toward them (Berry, 2006). Additionally, literature has highlighted a strong and positive relationship between intercultural contact and positive attitudes toward immigrants. Those members of the host culture who have more interaction with foreigners in working, academic or social settings, tend to exhibit a more positive attitude toward them and, as a consequence, a reduction of prejudice about their costumes (Pettigrew & Troop, 2000).

Masgoret and Ward’s model was empirically tested using structural equation modeling with the sample of 182 host students from the previous study. It was hypothesized that multicultural beliefs and intergroup anxiety would determine both perceptions of threat, real and symbolic, which in turn would influence on the attitudes that favor an effective intercultural contact.

As shown in Fig. 5.2, the obtained model presents a very good fit (χ2 = 17.76, ns; χ2/gl = 1.48, GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.83, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06). In relation to the prediction of intercultural contact, it was observed that positive attitudes appeared as the main predictor, with a direct influence on the outcome variable. Social Psychology has repeatedly mentioned the importance of negative attitudes in the prediction of intercultural contact (Jackson, Brown, Brown, & Marks, 2001). Additionally, attitudes have been found to be influenced by the perception of threats. The lower the perception of threat, the more positive the attitude and therefore, the greater the intercultural contact. Moreover, threats are also influenced by more distal variables, such as intergroup anxiety. Although in the present study it was possible to verify a positive influence of intergroup anxiety on the perception of threat, its impact was relatively weak and it only explained a small portion of the variance. It was also found that intergroup anxiety did not directly explain intercultural contact, it only played a role mediated by the effect of perceived threats and attitudes.

Several research studies showed that a society that values multiculturalism, which promotes positive attitudes toward integration and enhances cultural diversity, generally manifests greater respect for diversity, greater acceptance of immigrants and a reduction of negative prejudices (Berry, 2006; Berry, Kalin, & Taylor, 1977). In the current model, multicultural ideology had an influence on perceived threats, but did not explain intercultural contact. As in Berry’s model, this variable was only explained by multicultural ideology which was mediated by the effect of threats and attitudes. Moreover, these findings are also in line with the results of a model tested by Ward and Masgoret (2006). Although the model of the present study is not identical to the mentioned authors, similar relationships among variables were observed with a lower effect size and explaining a smaller proportion of the variance of intercultural contact.

4 Who Are the Most Successful International Students?

To succeed in the immigration process, international students should be able to adapt psychologically and culturally (Searle & Ward, 1990; Ward, 2004). While these two types of adjustments are considered separately, they are empirically related. Migrants should be able to maintain their psychological well-being similar to their levels prior to the cultural contact (psychological adjustment), while also being able to implement a set of skills or competencies in order to properly function in a culture different from their own (sociocultural adaptation). While both adaptations are important, literature has focused more frequently on sociocultural adaptation.

4.1 Cultural, Psychological and Socio-demographic Predictors of Cultural and Academic Adaptation

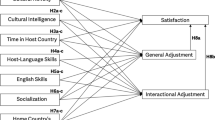

There is an extensive literature review on predictors of sociocultural adaptation success for international students (see Bochner, 2006 for a complete review). Overall, there are a small number of studies conducted in Latin American countries. Following, a research study conducted in Argentina which aimed to identify predictors of cultural and academic adaptation based on international students’ sociodemographic, cultural and psychological variables will be described.

The sample consisted of 217 international students attending various university courses. Their mean age was 24 years old and the majority of students came from other Latin-American countries (86 %). Only a small percentage came from European and Asian countries (14 %).

Table 5.4 presents predictor variables considered in the study. Adaptation measures taking into account for this research were: (a) academic adjustment, assessed by two items which include average grade obtained and self-perceived performance in their studies; and (b) cultural adaptation, assessed by four items which comprise daily life adaptation, quality of the stay and adjustment to the host culture.

The relationship between predictors and criterion variables – academic and cultural adaptation – was analyzed by two hierarchical regression analyses. Predictor variables were introduced in three steps in order to examine their contribution to the variance. Firstly, sociodemographic variables were introduced (age, sex and length of stay). In the second step, cultural variables were included in the analysis (contact with co-national, local and other international students, cultural distance, intergroup anxiety, and perceived discrimination). Finally, psychological variables were introduced (perceived social support, life satisfaction and perceived symptoms).

Overall, sociodemographic, psychological and cultural variables accounted for 56 % of the variance of sociocultural adaptation (Fig. 5.3). In particular, cultural variables together explained 42 % of the variance of the criterion variable, while psychological predictors provided an additional 13.5 %. Sociodemographic predictors only explained 0.05 % of the variance of cultural adaptation. Standardized regression coefficients showed that perceived discrimination, cultural anxiety and symptoms negatively predicted cultural adaptation. Contact with locals, social support and satisfaction also predicted, although in a positive direction, an effective cultural adaptation. It was concluded that three of the cultural variables introduced were able to predict almost half the variance of an effective cultural adaptation, while psychological variables were able to predict cultural adaptation in a much lesser degree.

As shown in Fig. 5.4, when predicting academic adjustment, cultural and psychological variables together explained 26 % of the variance. While cultural variables explained 12 % of the variance of academic adjustment, psychological predictors contributed an additional 14 %. In particular, sociodemographic variable did not explain its variance (0.01 %). An analysis of the standardized regression coefficients showed that perceived discrimination and intergroup anxiety negatively predicted academic adjustment while social support and life satisfaction positively predicted this variable.

This study demonstrates the importance of cultural variables in effective acculturation. However, both cultural and psychological predictors had a much smaller weight in relation to academic adjustment.

4.2 Strengths of Character, Cultural and Academic Adjustment

Positive Psychology brings the study of virtues and strengths as a sound basis for describing personality. Its study is pivotal as both individuals’ – positive emotions – and groups’ – positive organizations – experiences are supported by people’s strengths of character (Park & Peterson, 2009). Individuals possess different strengths and virtues, in varying degrees, that understood in positive terms are the essence of personality (McCullough & Snyder, 2000). Several empirical findings demonstrated that certain groups of strengths are associated with psychological well-being. These strengths are also associated with academic performance, act as protectors of certain psychological disorders and tend to increase as a result of having gone through traumatic events (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012; Park, Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2006; Peterson et al., 2008). Keeping these findings in mind, a study was designed in order to identify undergraduate students’ strengths of character, analyzing their relationship with psychological and cultural adaptation, as a result of the adjustment to a new cultural context.

The sample consisted of the same students from the previous research, 217 international students, who enrolled in various universities and stemming Latin-American countries (86 %). Strengths were assessed using a self-report questionnaire based on Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) classification of 6 virtues and 24 strengths of character. This instrument presents opposite self-descriptions, one with the presence of a strength of character and other one with the absence of it (Refer to Chap. 6, for regional data on this instrument). Participants should indicate the degree of similarity to each of the proposed self-descriptions. Additionally, life satisfaction was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) and academic and cultural adaptation with an instrument similar to the one described for the previous study.

First, Pearson’s correlations were conducted among virtues, academic adjustment, cultural adaptation and life satisfaction. Results showed that most virtues correlate with the three variables related to students’ adaptation (Table 5.5). That is, having greater virtues facilitates students’ general adjustment. Secondly, three regression analyses were run in order to assess variable relationships, virtues were entered as independent variables and academic adjustment, cultural adaptation and life satisfaction as dependent variables.

When focusing on the prediction of academic adjustment, virtues accounted for 15 % of the variance. An analysis of the standardized regression coefficients showed that courage and justice in particular were able to predict academic adjustment. International students who achieved better academic adjustment were those who had the will to reach their goals despite the barriers and obstacles faced. In addition, these students were also more committed to their social group and displayed more equitable behavior.

In terms of cultural adaptation, results showed that virtues explained 12 % of its variance. A detailed observation of the standardized regression coefficients showed that humanity was able to predict international students’ cultural adaptation. Those students who presented better adaptation to the new culture were those who also cared for others’ well-being, acting with benevolence, being generous and promoting fair relationship with others.

When exploring life satisfaction prediction, virtues accounted for 12 % of the variance. An analysis of standardized regression coefficients showed that virtues such as justice and courage were able to predict international students’ life satisfaction, presenting a similar pattern to the one found for academic adjustment.

In conclusion, the most adapted students were those who better overcame obstacles they had faced and had more energy to achieve their goals (courage). Moreover, they showed greater commitment with their social group (humanity) and displayed more equitable behavior (justice). These results are consistent with the critical task they were meant to develop. A successful acculturation process demands on the one hand, the resolution of practical problems of a psychosocial nature, which require a repertoire of social-oriented behavior. It demands interpersonal skills as those implied by the virtue of justice. On the other hand, when people are not able to adapt to an unfamiliar context acculturation might lead to acculturative stress. In this case, the new cultural context is seen as the main stressor. In this sort of situation, persistence, integrity, vitality and bravery – strength belonging to the virtue courage – are particularly important to achieve acculturation. These virtues, related to the motivation needed to acculturate, bring the perseverance and the will to make a constant effort to overcome obstacles in adverse circumstances.

Although the effect size for the predictions mentioned above are relatively small, this study highlights the importance of considering strengths and virtues in psychological and socio-cultural adaptation when working with international students.

4.3 Cultural Sensitivity and Cultural Intelligence as Cultural Competences

To succeed in the acculturation process, immigrants should possess what some authors named as cultural competences. Even though there is no agreement on what defines this concept, almost all authors agree on its importance (Cunningham, Foster, & Henggeler, 2002). This construct is relatively new and valuable in areas where it is necessary to interact with people from different cultural backgrounds: organizational leadership, medical professions, counseling, social services and educational contexts (Chi-Yue & Ying-Yi, 2007). Cultural competences include self-awareness of cultural values, knowledge of those who have opposed cultural values or different from themselves, adapting their own behavior to the needs of culturally diverse groups (Ang, Van Dyne, Koh & Ng, 2004; Chi-Yue & Ying-Yi, 2007; Cunningham et al., 2002; Earley & Ang, 2003; Flavell, 1979; Sternberg, 1986).

Following Bennett and Bennett (2004), intercultural competence can be defined as the ability to communicate and interact effectively in diverse cultural contexts. Even though the emphasis is on behavior, this cannot be considered without taking into account thoughts and emotions. Intercultural competences can be divided into two distinct groups: (a) cultural sensitivity (cultural mindset), which implies that one is aware of functioning in a cultural context which comprises its own rules and values, often different from one’s own. This includes attitudes such as curiosity toward diversity and tolerance of ambiguity. It is an attitudinal and representational domain toward diversity. (b) intercultural skills (cultural skill set) which involve the effective display of behavior in a diverse cultural situation. This includes the ability to analyze the interaction, to predict potential mistakes and to adapt behavior according to the context. There are a series of alternative behaviors that allow people to succeed in a new cultural situation. This domain relates to competencies and requires effective skill implementation. Some authors have named this component as cultural intelligence (Ang et al., 2007).

The basic idea of this two-component model is that knowledge, attitude and behavior must work together in order to succeed in the adaptation to different cultural context (Hammer, Bennett & Wiseman, 2003; Klopf, 2001; Lustig & Koester, 1999). This model posits that a different culture experience becomes more sophisticated when an individual has more opportunities to interact in different cultural contexts, moving from more ethnocentric to more ethnorelative stages. In the latter, one’s culture is put into perspective while it is experienced in relation to different cultural contexts.

Next, two research studies are presented. The first study was an attempt to validate a questionnaire based on Bennett and Bennett’s (2004) model previously described. The second study consisted of a design of a cultural intelligence test based on Early and Ang’s (2003) model.

Three groups of students participated in the design of the cultural sensitivity scale: (a) 105 military students (cadets) who were completing their academic and military 4-years training (mean age of 23 years-old); b) 187 undergraduate students who were enrolled in Psychology (mean age of 27 years-old); and c) 81 international university students who were enrolled in Argentinean universities (mean age of 24 years-old). Some examples of items that belong to the tests are presented below:

Nowadays, it is necessary to understand things from different “cultural” points of view. |

The more cultures one knows, the more differences one finds, which is a good thing. |

It is possible to hold ones’ beliefs while respecting others’ values when they are different from one’s own. |

People should know more about different countries’ traditions and customs. |

If a person travels for working or educational reasons, it is good to know that there are cultural differences between countries. |

It is good to have different opinions among people. If we all think in the same way, it might be boring. |

The cultural sensitivity scale was able to differentiate among groups of students with different cultural competencies. So it was expected that students in the acculturation process would be more aware of cultural differences (greater cultural sensitivity) compared to students who had no prior experience of migration nor exposition to intercultural exchange. Previous studies have shown that military students predominantly hold values such as conservation and tradition, with a strong ethnocentric perspective (Castro Solano, 2005; Castro Solano & Nader, 2004). Therefore, it was expected that this group would be the least sensitive to diversity compared to their counterparts. Figure 5.5 presents means obtained for cultural sensitivity in each of the three groups studied.

As can be seen in Fig. 5.5, military students obtained the lowest scores, local students achieved intermediate scores and students in the acculturation process reached the higher scores on cultural sensitivity (F(2,370) = 58.19, p < .001). Thus, it can be concluded that closer groups have lower levels of tolerance for diversity compared to groups who are more accustomed to having intercultural contact, as international students.

Cultural sensitivity (cultural mindset) would be the first stage in assessing migrants’ cultural competences. The more individuals are exposed to different cultural environments, the higher levels of cultural sensitivity they will experience. That is, they would be less ethnocentric and would present higher levels of tolerance to those aspects of the context that are different from, even contrasting to, their beliefs and values. Secondly, effective displayed behavior in a diverse cultural context (cultural skill-set) should be assessed when evaluating individuals’ cultural competences. Moreover, it should be considered the manner in which most competent individuals are able to adapt effectively to the new environment.

In order to assess this second stage, a new study was conducted, developing an instrument to measure cultural intelligence, based on Early and Ang’s (2003) conceptualization of the concept. These authors defined cultural intelligence as the ability to effectively adapt to a new cultural context, a multidimensional construct which comprises four components:

Metacognitive | Ability to acquire knowledge and understanding of cultural diversity |

Cognitive | Knowledge about rules and practices of different cultural backgrounds |

Motivational | Intrinsic interest in cultural differences |

Behavioral | Flexibility to adapt behavior to a cultural background different to one’s own. |

With the purpose of validating this instrument, 237 international students enrolled in Argentinean universities were recruited for the study. Mean age of participants was 24 years-old. This test consisted of a series of different vignettes in which individuals had to resolve a situation which involved cultural differences. The aim of this tool was to access to the actual behavior displayed in situations that involve intercultural exchange. Participants should respond to a total of 16 intercultural scenarios. Some examples of these descriptions are presented below:

-

1.

You are in the classroom and a question arises related to what the lecturer has just explained. Next to you there are two classmates, one from your own culture and the other one from a different cultural background. (a) you might ask either students as you believe both have understood. (b) you prefer to ask the student from your own culture, as you think he/she will better understand.

-

2.

You have received an invitation to dine out with a group of international students that you have recently met at the university. The chosen venue for the occasion is a typical restaurant from their country. You do not know any of the dishes they mentioned. How would you act in this situation? (a) You would attend but would not feel entirely comfortable. (b) You would order a typical dish and feel confident of being comfortable during the evening.

-

3.

You are in a different country and realize that your outfit strongly differentiates from what other people regularly wear. You decide: (a) continue dressing as you frequently do in your country. (b) going shopping in order to dress as other people.

It was hypothesized that students who possessed the ability to adapt to different cultural contexts would obtain high scores on the previously described test. Correlations were run for this measure of cultural intelligence and the following variables: sociocultural adaptation, intergroup anxiety, attitudes toward multiculturalism and frequency of contact with co-nationals and local students. As shown in Table 5.6, cultural intelligence presents moderate correlations with adjustment in general and sociocultural adaptation in particular.

In summary, students who better adapt to host countries are those who are more motivated by diversity and are able to adjust their behavior effectively according to the demands of a changing environment which is different from their own.

5 Conclusion

As it has been described throughout this chapter, students who are more sensitive to diversity, have greater abilities to integrate to a new culture, have more frequent interact with others and are also more committed to their social reference group, tend to have a positive cultural adaptation when they decide to study abroad. If, however, students decide to start university studies in countries with different values and a great culture distance from their own, if they hold to traditional values and tend to view their culture as unique, these students are more likely to be discriminated against and might present poor psychological and sociocultural adaptation.

One might ask what Positive Psychology brings to the study of successful acculturation of international students. Firstly, it is important to consider that not all students would be able to maintain their psychological well-being when experiencing a migratory process. The ability to adapt to different cultural environments, the sensitivity to understand diversity, the skills to build social networks, and the virtues of humanity, courage and justice are the cornerstones of a positive adaptation. However, there are other characteristics related to the environment, rather than personal factors, that have an influence on an individuals’ adjustment. A culturally distant context in terms of values or a country that is not institutionally welcoming to immigrants would be obstacles to a successful acculturation process.

The key aspects of a successful immigration develop from an interaction between personal and contextual characteristics. Individuals’ strengths do not function independently; the environment might enhance or hold back the adaptation process. In general, Positive Psychology considers that strengths and positive emotions are the result of individuals’ characteristics or the outcome of an intentional activity designed to generate them. Under this perspective, the strong influence that contexts have on individuals’ behavior might be forgotten.

If country characteristics have an impact on the nature of contact international students have with the host society, and individuals’ competences moderate this impact, one might expect great differences in acculturating levels depending on this interaction of these two aspects. Thus, when working with international students, it is important to understand both students’ characteristics and cultural background and the uniqueness of the receiving university and society they will immerse in. This interrelationship is essential to achieve an effective adaptation and therefore, to accomplish their academic goals. This successful endeavour would consequently lead to benefits for both sojourners and the host society.

References

Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71(5), 319–342. doi:10.1037/h0027352.

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2004). The measurement of cultural intelligence. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Meetings symposium on cultural intelligence in the 21st century, New Orleans, LA.

Ang, S., Van Dynne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K., Tay, C., et al. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation, and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.x.

Baubock, R., Heller, A., & Zolberg, A. (1996). The challenge of diversity: Integration and pluralism in societies of immigration. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

Bennett, J. M., & Bennett, M. J. (2004). Developing intercultural sensitivity: An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In D. J. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp.147–166). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(1), 5–68. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. Chun, P. Balls-Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research (pp.17–37). Washington, DC: APA Press.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

Berry, J. W. (2006). Mutual attitudes among immigrants and ethnocultural groups in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Research, 30, 719–734. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.06.004.

Berry, J. W., Kalin, R., & Taylor, D. M. (1977). Multiculturalism and ethnic attitudes in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Ministry of Supply and Services.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006a). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006b). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(3), 303–332. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x.

Bochner, S. (1981). The mediating person: Bridges between cultures. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

Bochner, S. (2006). Sojourners. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp.181–197). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bourhis, R. Y., Moise, L. C., Perreault, S., & Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32(6), 369–386. doi:10.1080/002075997400629.

Castro Solano, A. (2005). Técnicas de evaluación psicológica en ámbitos militares [Assessment techniques in military settings]. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidos.

Castro Solano, A. (2011). Aculturación de estudiantes extranjeros: Estrategias de aculturación y adaptación psicológica y sociocultural de estudiantes extranjeros en la Argentina [Acculturation strategies and psychological and sociocultural adaptation of foreign students in Argentina]. Interdisciplinaria, 28, 115–130.

Castro Solano, A., & Nader, M. (2004). Valoración de un programa de entrenamiento académico y militar de cadetes argentinos [Evaluation of an academic and military training programme with Argentine cadets: Values and leadership styles]. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica, 17, 75–105.

Chi-Yue, C. H., & Ying-Yi, H. (2007). Culture: Dynamic processes. In A. Elliot & C. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 489–505). New York: The Guilford Press.

Church, A. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 540–572. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.91.3.540.

Cosentino, A., & Castro Solano, A. (2012). Character strengths a study of Argentinean soldiers. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 199–215.

Cunningham, P., Foster, S., & Henggeler, S. (2002). The elusive concept of cultural competence. Children Services: Social Policy, Research and Practice, 5, 231–243. doi:10.1207/S15326918CS0503_7.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Earley, P. C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ellingboe, B. J. (1998). Divisional strategies to internationalise a campus portrait: Results, resistance and recommendations from a case study at a U.S. university. In J. A. Mestenhauser & B. J. Ellingboe (Eds.), Reforming the higher education curriculum: Internationalising the campus (pp.179–197). Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education.

Filmus, D. (2007). Síntesis del discurso del día 10 de Julio de 2007 [Summary of the speech, July 10, 2007]. Retrieved from http://www.me.gov.ar/spu/Noticias/

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring. A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 705–712. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.34.10.906.

Furnham, A., & Alibhai, N. (1985). The friendship networks of foreign students: A replication and extension of the functional model. International Journal of Psychology, 20(6), 709–722. doi:10.1080/00207598508247565.

Furnham, A., & Bochner, S. (1986). Culture shock: Psychological reactions to unfamiliar environments. London: Methuen.

Gil, A. G., Vega, W. A., & Dimas, J. M. (1994). Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(1), 43–54. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199.401)22:01<43::AID-JCOP2290220106>3.0.CO,2-T.

Gordon, M. (1964). Assimilation in American life. London: Oxford University Press.

Haddock, G., Zanna, M. P., & Esses, V. M. (1994). The (limited) role of trait-laden stereotypes on predicting attitudes toward native peoples. British Journal of Social Psychology, 87, 259–267. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1994.tb01012.x.

Hammer, M., Bennett, M., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 421–443. doi:10.1016/S0147-1767.

Holmes, P. (2005). Teachers’ perceptions of and interactions with international students: A qualitative analysis. In C. Ward, A. M. Masgoret, E. Ho, P. Holmes, J. Newton, D. Crabbe, & J. Cooper (Eds.), Interactions with international students (pp.86–119). Wellington, New Zealand: Report for Education New Zealand.

Jackson, J. S., Brown, K. T., Brown, T. N., & Marks, B. (2001). Contemporary immigration policy orientation among dominant-group-members in Western Europe. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 431–456. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00222.

Klopf, D. (2001). Intercultural encounters: The fundamentals of intercultural communication (5th ed.). Englewood, CO: Morton.

Lin, J. G., & Yi, J. K. (1997). International student’s adjustment: Issues and program suggestion. College Student Journal, 31(4), 473–479.

Lustig, M., & Koester, J. (1999). Intercultural competence: Interpersonal communication across cultures (3rd ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley Longman.

McCullough, M. E., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Classical sources of human strength: Revisiting an old home and building a new one. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 1–10. doi:10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.1.

Mills, C. (1997). Interaction in classes at a New Zealand university: Some international students’ experiences. New Zealand Journal of Adult Learning, 25, 54–71.

Ong, A., & Ward, C. (2005). The construction and validation of a social support measure for Sojourners: The Index of Sojourner Social Support (ISSS) Scale. The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(6), 637–661. doi:10.1177/0022022105280508.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Strengths of character in schools. In R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, & M. J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp.65–76). New York: Routledge.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 23, 603–619. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748.

Peterson, C., Park, N., Pole, N., D’Andrea, W., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Strengths of character and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress., 21, 214–217. doi:10.1002/jts.20332.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Greater strengths of character and recovery from illness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 17–26. doi:10.1080/17439760500372739.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Troop, L. (2000). Does intergroup contact reduce prejudice: Recent metaanalytic findings. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp.93–114). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence.

Rodriguez Gomez, R. (2005). Migración de estudiantes: Un aspecto del comercio internacional de servicios de educación superior. [Migration of students: An aspect of the international commerce of superior education services]. Papeles de Población, 44, 221–238.

Rodriguez, N., Myers, H. F., Bingham, C., Flores, M. T., & Garcia-Hernandez, L. (2002). Development of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory for adults of Mexican origin. American Psychological Association, 14(4), 451–461. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.451.

Searle, W., & Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14(4), 449–464. doi:10.1016/0147-1767 (90) 90030-Z.

Smart, D., Volet, S., & Ang, G. (2000). Fostering social cohesion in universities: Bridging the cultural divide. Canberra, Australia: Australian Education International Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

Smith, A. (1998). New survey reveals changing attitudes. American Language Review, 2, 28–29.

Spencer-Rodgers, J. (2001). Consensual and individual stereotypic beliefs about international students among American host nationals. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25(6), 639–657. doi:10.1016/S0147-1767(01)00029-3.

Spencer-Rodgers, J., & McGovern, T. (2002). Attitudes towards the culturally different: The role of intercultural communication barriers, affective responses, consensual stereotypes, and perceived threat. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26(6), 609–631. doi:10.1016/S0147-1767 (02) 00038-X.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3), 157–175. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp.23–45). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119–135. doi:10.1037//0033-295X.93.2.119.

Ward, C. (1999). Models and measurements of acculturation. In W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, D. K. Forgays, & S. A. Hayes (Eds.), Merging past, present and future (pp.221–229). Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Ward, C. (2004). Psychological theories of culture contact and their implications for intercultural training and interventions. In D. Landis & J. Bennet (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp.185–216). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ward, C. (2006). Acculturation, identity and adaptation in dual heritage adolescents. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2), 243–259. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.09.001.

Ward, C., Berno, T., & Kennedy, A. (2000, September). The expectations of international students for study abroad. Paper presented at the International Conference on Education and Migrant Societies, Singapore.

Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock. London: Routledge.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1994). Acculturation strategies, psychological adjustment and socio-cultural competence during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18, 329–343. doi:10.1016/0147-1767.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1999). The measurement of sociocultural adaption. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(4), 659–677.

Ward, C., Larissa Kus, X., & Masgoret, A. (2008, July). Acculturation and intercultural perceptions: What I think, what you think, what I think you think and why it’s all important. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the 19th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Bremen, Germany.

Ward, C., & Leong, C. H. (2006). Intercultural relations in plural societies: Theory, research and application. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ward, C., & Masgoret. A. (2004). The experiences of international students in New Zealand: report on the results of the national survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz

Ward, C., & Masgoret, A.-M. (2005a). Attitudes toward immigrants and immigration. Paper presented at new directions, new settlers, new challenges, FRST end-users seminar, Wellington, New Zealand.

Ward, C., & Masgoret, A.-M. (2005b). New Zealand students’ perceptions of and interactions with international students. In C. Ward (Ed.), Interactions with international students (pp.2–42). Wellington, New Zealand: CACR and Education New Zealand.

Ward, C., & Masgoret, A. M. (2006). An integrative model toward immigrants. Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 671–682.

Williams, C. L., & Berry, J. W. (1991). Primary prevention of acculturative stress among refugees: Application of psychological theory and practice. American Psychologist, 46(6), 632–641.

Yang, B., Teraoka, M., Eichenfield, G. A., & Audas, M. C. (1994). Meaningful relationships between Asian international and U.S. college students: A descriptive study. College Student Journal, 28, 108–115.

Zlobina, A., Basabe, N., Paez, D., & Furnham, A. (2008). Sociocultural adjustment of immigrants: Universal and group-specific predictors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2), 195–211.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Castro Solano, A., Aristegui, I. (2014). Cultural Competences of International Students: Its Role on Successful Sociocultural and Psychological Adaptation. In: Castro Solano, A. (eds) Positive Psychology in Latin America. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology, vol 10. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9034-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9035-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)