Abstract

The study of social behavior is relevant to the promotion of psychological health in children and adolescents. In recent decades, studies on social skills have shown a relationship between social competence and mental and physical health, when considering the repertoire of social skills as a protective factor. Social skills, besides being a significant predictor of academic performance, have been considered indicators of healthy development and quality of life. There is evidence that social skills that enable mutually satisfying relationships, promote prosocial behavior and greater well-being. Thus, their identification is essential for the development of strength and positive capacities. The purpose of this chapter is to describe three studies focused on the assessment of social skills among children living in the northwestern region of Argentina. The first study involves the design and validation of a hetero-informed tool and a record observation of children between 3 and 5 years old; the second study analyzes the relationship between dysfunctional behaviors and social skills in children enrolled at initial educational level; and the third study proposes an intervention to develop social skills in school-aged children. These studies highlight the role of context in the expression of social behaviors, particularly in poor urban areas. The scope, limitations and contributions of the empirical evidence are analyzed and presented.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The study of social abilities has expanded greatly during the last 50 years, especially in different fields of psychology. According to Kirchner (1997), research began in the 1930s with studies of assertive behavior in children (Murphy, Murphy, & Newcomb, 1937; Williams, 1935) and resurfaced in the 1960s and 1970s in England and the USA with a cognitive-behavioral approach. Early studies focused on the evaluation and training of social behavior associated with psychological disorders. However, over the last decades, this negative conception of social skills has been supplemented with the study of the promotion of social competence and positive qualities such as prosocial and cooperative behavior.

Various evaluations have pointed out that between 7 and 10 % of the general population has some type of difficulty in the expression of social skills, which would be considered as a deficit in social competence (Hecht, Genzwurker, Helle, & Calker, 2005; Hecht & Wittchen, 1988). In Argentina, the ‘Mental Health and Addictions Watch System’ [Sistema de Vigilancia en Salud Mental y Adicciones] estimated in 2010 that over 30 % of the population above the age of 15 suffered from mental and behavioral disorders (Ministry of Health, 2010), which involved a deficit in social skills. These epidemiological data show that social deficits are involved in the genesis and manifestation of such disorders, so that the early identification of social skills is an important factor in the prevention of psychopathologies.

Social skills are one of the most widely studied protective factors in infant-juvenile mental health (Diaz-Sibaja, Trujillo, & Peris-Mencheta, 2007) since a person’s ability to use his assertive abilities within the context in which he lives allows him to reach a satisfactory social adjustment. In turn, reinforcement from others strengthens a positive valuation of the individual’s social behavior, which is reflected in his self-esteem, a very important component of his personality. From a salutogenic perspective, social skills are positive resources, especially those that make possible mutually satisfactory relationships and promote prosocial behaviors. There is a general consensus that assertive abilities and relationships with peers in childhood contribute to an adequate interpersonal functioning and favor the development of reciprocity, empathy, collaboration, cooperation, positive emotions and well-being. In this connection, Segrin and Taylor (2007) suggested that if social skills are associated with positive responses such as gratification, they will strengthen positive relations with others. According to these authors, positive relationships provide a link between social skills and the positive experiences of well-being.

Del Prette and Del Prette (2008) consider that social skills are those social behaviors included in a person’s repertoire that contribute to his social competence, favoring the efficacy of the interactions he establishes with others. Although this is a complex construct, there is a consensus with respect to considering social skills as learned behavior (Monjas Casares, 2002) that favors positive relationships (Segrin & Taylor, 2007), increases the possibility of social reinforcement and problem resolution without aggressiveness (Reyna & Brussino, 2011) and expresses a person’s feelings, attitudes, desires, opinions or rights in a way that is adequate to a particular situation (Caballo, 2005). Although social competence and social skills were considered synonymous, the former includes these abilities, which in turn are part of adaptive behavior (Gresham & Rechly, 1988). From the point of view of evaluation, social competence is a cumulative measure of an individual’s social performance in different situations that are evaluated by significant social agents according to norms, rules and criteria within a sociocultural frame of reference.

As Caballo (2005) points out, social skills are a link between a person and his context, since the social condition that defines a human being highlights his ability to use his social skills. The way in which an individual practices these acquired resourced defines the quality of his social skills. This author points out that a good repertoire of social skills is expressed through assertive behavior, that is, behavior that is fair, efficient and specific for the situation. This implies the development of a balance between inhibited, passive and aggressive behavior, although this implies that on certain occasions the response will be passive or aggressive. We should remember that, as Kelly (1987) pointed out, a socially skilled individual is one that displays efficient behavior within an interpersonal situation, managing to obtain or maintain the reinforcement of his environment.

Social behavior is learned throughout a person’s life cycle, so that the ability to relate to others, stand for one’s rights, express one’s opinions and feelings or face criticism, among other abilities, depends on the process of socialization. Different approaches agree that this process starts at birth (Dunn, 1988; Kaye, 1982), while biological models hold that children may be born with a tendency toward a certain temperament and that their behavioral manifestation would be related to an inherited physiological bias that could mediate the way in which they respond (Caballo, 2005). In this way, early learning experiences could interact with biological predispositions that would determine certain patterns of social functioning. According to Buck (1991), temperament will determine the nature of the interpersonal socio-emotional environment and will also influence the ability to learn. Thus, temperament would determine emotional expressiveness, which in turn would favor the development of social abilities and social competence.

Although biological aspects are a basic determinant of behavior, especially in early social experiences, the development of social skills depends on growth and social experiences. According to Meichenbaum, Butler, and Grudson (1981), social skills develop within a cultural framework and, consequently, within communication patterns that correspond to a particular culture. Furnham’s studies (1979) show how social skills that are relevant in one culture may be irrelevant in others. For example, he mentions that assertiveness is considered in some countries as an index of mental health, while in other cultures is neither promoted nor accepted: “humility, subordination and tolerance are more strongly valued than assertiveness in many cultures, especially in the case of women. Even more, lack of assertiveness is not necessarily a sign of insufficiency or anxiety, although it may be so at times” (Furnham 1979, p. 522).

Although the Social Learning Theory has not proposed a model of social skills, its guidelines allow us to understand social behavior as the result of intrinsic factors (belonging to the subject) and extrinsic ones (belonging to the environment) (Bandura, 1987). For Bellack and Morrison (1982), the guidelines of this theory would account for the early acquisition of social behavior, especially modeling and reinforcement. Children learn behavioral patterns, relational styles and social skills through the modeling and imitation of their parents or caretakers, which are later generalized into other socializing contexts such as the school environment and his peer group. The latter plays a decisive role in the reinforcement of social abilities, especially during adolescence.

This chapter deals with the study of social skills in childhood with an emphasis on the influence of vulnerability conditions. The consideration of vulnerability points back to the fragility of the personal, familiar-relational, political and especially socioeconomic environment of the children involved, which places them within an at-risk population group. Focus is placed on the identification not only of social deficits but also of those social skills that act as protective factors for children. Developments center on three relevant topics: (a) how to evaluate social skills in children, (b) the relationship between social skills and behavioral problems in childhood, and (c) the modification of social behaviors. In order to illustrate the above, empirical studies conducted in a children population in northwestern Argentina are described, the product of a line of research that from 2003 to this date has been developed in the Faculty of Psychology of the National University of Tucuman [Facultad de Psicologia of the Universidad Nacional de Tucumán], with grants from the Argentinean National Council of Scientific and Technological Research.

2 The Evaluation of Social Skills in Children

If measurement in psychological sciences is difficult since it must reflect the relationships between observable behavior and concepts, this difficulty is even greater in the measurement of social skills. An article published in 1979 in the Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment describes the controversies and obstacles for the evaluation of these skills. Curran (1979) claimed that social skills are a mega-construct in which one tends to associate a variety of superficially plausible behaviors, so that their evaluation supposes the revision of psychometric theories and methodological strategies that enable the evaluation not only of behavioral aspects but also of cognitive factors and emotional states involved in social skills. According to Caballo (2005), the greatest difficulty in evaluation lies in the social nature of the interactions, in the lack of agreement on the concept of social skills and in the significant external criteria with which to validate the procedures.

The aim of the evaluation of social skills is the identification of interpersonal behaviors, which implies a pre-test/post-test evaluation process, that is, an evaluation before and after the processes of training and learning of social behavior (Monjas Casares, 2002). According to Sendin (2000), during childhood this evaluation is individualized (considering the evolutive level, the cultural factors, the characteristics and the needs of the child), interactive and contextual (because of the context of interaction, the people involved and the relevant interpersonal situations) and informative (because of the relevant diagnostic data for intervention). These peculiarities explain the usefulness of a multi-method and multi-informant approach, which are characteristics pertaining to child psychological evaluation (Forns & Santacana, 1993). Multi-method implies the combination of methods and especially techniques of a quantitative and qualitative nature (interviews, observations, inventories, among others) tending to increase diagnostic precision. The multiinformant condition implies that the information necessary to elaborate the diagnoses should be gathered from different sources of information: parents, teachers, peers, and the child himself. In practice, the multi-method and multi-informant perspective is not the one most often used in the exploration of social behavior because of the context of application, the number of evaluators involved, and the time allowed for the evaluation process, among other reasons. Other arguments mention the obstacles inherent in the definitions of social skills and competences recognized by the scientific community such as the almost exclusive development of specific and unspecific tests or tools only for adults or adolescents.

2.1 Formats to Evaluate Social Skills

For Monjas Casares (2002), the most often used tools in child evaluation of social competence and skills are: (a) information from other people (parents, peers, teachers) through scales and questionnaires, (b) direct observation in natural or artificial situations and (c) interviews and self-reports. In school environments, it is common to use students’ output (summaries, oral productions, body language, and drawing), a systematic observation, anecdotes, report sheets and evolution charts. However, the scarce availability of validated tools or the lack of tests for certain age groups has limited the multi-method and multi-informant perspective. A recent study by Reyna and Brussino (2011) showed that the scale of evaluation of social abilities such as a single informant’s report is the most usual one in child behavior research in Latin America.

Numerous research teams have conducted studies of the evaluation of children’s social skills in Latin America. For instance, the group Relações Interpessoais e Habilidades Sociais (RIHS) coordinated by Drs. Almir del Prette and Zilda Del Prette in the University Federal of Sao Carlos, Brazil, designed and validated a multimedia system of evaluation (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2003), sociometric registers (Goncalves & Murta, 2008; Molina & Del Prette, 2007), scales (Bandeira, Rocha, Freitas, Del Prette, & Del Prette, 2006) and observations (Cia, Pamplin, & Del Prette, 2006). In Bolivia, scales were used with both teachers and parents (Pichardo, García, Justicia, & Llanos, 2008) and also with children (Ferreyra & Reyes Benítez, 2011). In Colombia, a survey on aggressive and prosocial behaviors applicable to different informants was validated (Martínez, Cuevas, Arbeláez, & Franco, 2008) as well as a scale for parents concerning the social skills of small children (Isaza Valencia & Henao Líopez, 2011). In Venezuela, an interview for children was adapted within an intervention program on social skills (Amesty & Clinton, 2009). In Argentina, a socio-cognitive test for school children was adapted (Greco & Ison, 2009; Ison & Morelato, 2008), together with a scale for parents and teachers (Ipiña, Molina, & Reyna, 2010, 2011; Schulz, 2008), another one for children at the pre-school level (Reyna & Brussino, 2009), and the design and validation of a behavioral observation scale (Ison & Fachinelli, 1993).

2.2 Assessment Tools Developed to Evaluate Social Skills

Two assessment tools were developed to evaluate the social skills of pre-school children between the ages of three and five: a scale for parents or caretakers and an observation register of the social behavior of children within the school context.

2.3 Scale of Pre-school Social Skills (SPSS)

This is a scale constructed on the basis of other tools dealing with children social skills, evolution indicators and experts’ considerations. The final version of this tool emerged from a validation by judges and from the analysis of its psychometric properties. Three hundred and eighteen parents and/or caretakers of children attending the Primary Health Care Centers (CAPS) in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina were involved. The version for 3-year-olds included 20 items (α = .72), the one for 4-year-olds 23 items (α = .77) and the one for 5-year-olds 26 items (α = .86). Although exploratory factorial analyses were performed, the solutions were difficult to interpret and implied the elimination of items that assessed significant social behaviors (for instance, children’s ability to interact with adults), so it was decided that the scale would have a unifactorial structure, discriminating between children with high or low levels of social skills.

These are some of the items included in the test for different ages:

3 years old

-

Can tell his/her name when asked to do so (item 2)

-

Says “thank you” in his/her relationships with his/her parents (item 9)

-

Mentions praising both parents or one of them (item 10)

4 years old

-

Introduces him/herself spontaneously to other children (item 3)

-

Asks other children if he/she can help them in their activities (item 4)

-

Is kind to his/her parents and other known adults (item 9)

5 years old

-

Shows courteous behavior toward other children (uses phrases such as “please”, “thank you”, “sorry”) (item 5)

-

Helps a friend in trouble (item 8)

-

Can hold a simple conversation with an adult (item 16)

All the versions of this tool explored different areas of social abilities, especially those associated with the child’s interaction with his/her primary group and his/her peer group, for example: mentions approval when other children do something he/she likes (item 5, 3-year-olds), adapts him/herself to the games and/or activities that other children are already performing, (item 7, 3-year-olds); the resolution of conflictive situations with his/her peers (item 5: mentions approval when other children do something he/she likes, item 7: tries to understand the activities other children are performing, 4-year-old version) and indicators of cooperation and collaboration (item 4: asks other children if he/she can help them in their activities and item 9: is kind to his/her parents and other known adults, 4-year-old version; item 4: does small favors to other children, (item 8: helps a friend in trouble, 5-year-old version). The expression of positive emotions toward parents or other known adults (item 15: mentions praising his/her parents or other known adults (e.g. his/her teacher)) was also included in this scale.

2.4 Register of Observation of Social Skills (ROSS)

Although observation has been traditionally associated with inductive reasoning of a qualitative kind, this register was designed on the basis of a quantitative methodology. In its design we considered the ‘Observation Code of Social Interaction’ (Código de Observación de la Interacción Social) (COIS) (Monjas Casares, Arias, & Verdugo, 1991) and the observations performed in Maternity Care Centers in S.M.de Tucumán. The tool consists of 12 items, in which the child’s interactions or their absence with peers and/or adults are considered. It includes mutually exclusive categories of interactive and non-interactive behaviors to prevent some behaviors from being assigned to the same category. The register explores the inclusion of one or several classmates as well as the nature or the interaction (positive or aggressive) and its expressions (verbal, physical or both).

This version was applied to 89 children aged 4–5 attending public kindergartens in San Miguel de Tucumán (Argentina). It should be noted that the context of evaluation was the playground or the schoolroom when the children were playing.

Validation was based on the judge system. We did not perform another psychometric analysis due to the loss of registered cases during the data collection period. It should be pointed out that the test was administered by an external evaluator so that the observation data would be reliable and not liable to subjective bias from the main evaluator. As Sanz, Gil, and García-Vera (1998) stated, observation implies a series of practical and psychometrical problems, since although the fact that a child approaches another is simple to observe and evaluate, it is also necessary to consider the social validity of this chosen analysis unit and the way to codify it.

2.5 Evaluation of Social Skills in Children with Nutritional Deficits

SPSS and ROSS were used to analyze the social skills of 318 pre-school children in a situation of socioeconomic vulnerability living in San Miguel de Tucumán. The children were undergoing pediatric checkups in Primary Health Care Centers (CAPS) and were distributed into two groups: clinical (malnourished children) and control (eutrophic children) on the basis of a review of 733 medical records. The children in the clinical groups showed first degree malnutrition (deficit of up to 20 %) according to the anthropometric weight/size measurement, which started after they were 12 months old. All the children had been born in 2000–2002, the time of a serious socioeconomic crisis in Argentina. At the operational level, two variables defined poverty in the present study: the level of educational and the present occupation of parents or caretakers. The combination of these factors established a higher and a lower level of poverty. The lower level included those parents with formal education above complete primary education and with steady, low quality jobs. The higher level included those parents with a minimum educational level and unstable jobs or jobs related only to social relief programs. The determination of such categories was due to the great heterogeneity of the data obtained in the sociodemographic survey administered together with the SPSS.

The results indicated that both eutrophic and malnourished children had the basic social skills necessary to deal with everyday situations, since no statistically significant differences were observed between them. Despite their socioeconomic vulnerability, these children were able to acquire a series of social skills. For example, they were able to greet other people, tell their name, adapt to other children’s games, praise their parents, tell other people when another child did something that was unpleasant to them, show initiative to relate to unknown peers, display cooperative behaviors and express positive feelings in their interactions with adults (Lacunza & Contini, 2009). However, the mere presence of social behaviors does not determine whether or not a child is socially competent; this repertoire of social skills should be exercised in a specific situation and be positively valued to consider the child’s actions as competent. Consequently, the most skilled child is not the one with the greatest number of social behaviors, but the one capable of perceiving and discriminating signals within a given context and choosing a combination of behaviors that is adequate for that particular situation.

In conclusion, according to parental perception, children in Tucumán with and without malnutrition showed the social behavior necessary for daily life, which enabled their psychological adjustment to their immediate context. The social relationships that these children established could be considered as a health protecting factor, insofar as the use of these social skills contributes to their adaptive functioning. It should be remembered that children in situations of poverty must face an environment characterized by uncertainty and stressful stimuli. Although the resources to face those are scarce, this study determined that assertive social skills are capacities that allowed the active adaptation of the children, and therefore act as “shock absorbers” against the negative effects of poverty and social inequality.

In a subsample of children with the two tools (ROSS and SPSS) a statistically low positive relationship (r = .293, p < .01) was found. This correlation agrees with the findings of Mischell (1968) with respect to the low relation between tests of different nature in the evaluation of components of the personality. Different authors (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; Grietens et al., 2004) maintain that there usually is a low degree of agreement between the information provided by the different informants from the different contexts (parents and teacher or parents and the children themselves), while the degree of agreement may be moderate when the informants evaluate the child in the same context (e.g. mother and father or different teachers of the same child). This low agreement between informants could indicate that the variable to be evaluated differs according to the various situations and not that the contributions of the different informants are unreliable.

2.6 Evaluation of Social Skills of Urban and Rural Children

In a later study we evaluated the social skills of children belonging to urban and rural environments in Tucumán (Lacunza, 2012). SPSS was developed on a sample of 260 children aged 5 who attended public and private kindergartens. The families in the rural environment belong to contexts of low socioeconomic status (SES) and lived in a locality in the north of the province while the urban children lived in San Miguel de Tucumán, the capital of the province. According to parental perception, urban and rural children with low SES showed a similar profile of social skills, while urban children with high SES were described as having greater social skills than their peers with low SES. Twenty-five percent of urban children and 20 % of rural children with low SES rated above average (percentiles above 75), which allowed us to hypothesize that the social behaviors identified (salutations, relationships with unknown peers, expression of positive emotions, establishing a conversation with an adult, among others) acted as a positive factor of social competence and as a protecting factor against the effects of poverty. Urban and rural children with low SES were observed in the school environment. The application of ROSS showed that rural children differed statistically in their social skills with respect to urban children (t = −5.64, gl = 160, p = .000), although 97 % of the urban children showed positive interactions (relationships through play, activity or conversation) and 38 % initiated the approach, mainly to a peer (78 %). No statistically significant associations were found between the informant report and the observation, which confirms the above statement with respect to the situational specificity of social skills.

3 Social Skills and Behavior Problems in Infancy

Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated the connections between social competence and physical and mental health. For instance, a repertoire of assertive social skills is related to high levels of academic achievement and self esteem, emotional regulation and impulse control (Campo Ternera & Martinez de Biava, 2009; Elliot, DiPerna, Mroch, & Lang, 2004; García Nuñez del Arco, 2005; Inglés et al., 2009; Perez Fernandez & Garaigordobil Landazabal, 2004; Rubin et al., 2004). On the other hand, deficits in social skills are associated with a variety of disorders such as anxiety, cardiovascular disease and substance abuse (Semrud-Clikeman, 2007).

Existing literature indicates that problems in interpersonal relationships are found mainly in those children who relate poorly to their peers and avoid social contact and, on the other hand, in those who have violent relations with their peers (Monjas Casares, 2002). These behaviors are associated with inhibited and aggressive styles of interaction that evidence deficient social skills. According to Gresham (1988), two theoretical models can account for these social shortcomings: the deficit model and the interference model.

Social skills problems can be analyzed from two points of view. On the one hand, from the behavioral component of such skills, that is, the aggressiveness or inhibition in the interaction of the child with his/her parents and adults, and on the other, from the cognitive perspective, since the child perceives others with mistrust, according to certain attributes, and reacts with greater aggressiveness or withdrawal. Based on the behavioral dimension, we analyzed the relation between social skills and behavior problems in 185 children aged 5 who attended public and private kindergartens in San Miguel de Tucumán (Argentina). SPSS, the Behavioral Observation Guide (BOG) (Ison & Fachinelli, 1993) and a sociodemographic questionnaire were administered to parents and/or caretakers. It should be noted that the BOG explores behavior problems such as physical and/or verbal aggressiveness, denial, transgression, impulsiveness, hyperactivity, attention deficit, self aggression, inhibition and peer acceptance. The BOG was designed and validated with a child population in Mendoza (Argentina). With respect to sociodemographic indicators, education, parental occupation and access to goods and services defined SES. Low SES was already described in previous studies while high SES was indicated by completed university studies, managerial jobs, (chiefs, managers), professionals and owners of small and mid-sizes enterprises.

The results show that males in both SESs had behavior problems related to physical and/or verbal aggression and transgression to a greater degree than their female counterparts. Following the proposal of the authors of the BOG, a group of children was formed with those that showed disruptive behaviors (those with percentiles above 75 with respect to physical and/or verbal aggression and denial). Sixty-two percent of the total sample showed this condition.

Children with disruptive behaviors with low SES showed fewer social skills than children with the same problems with high SES. Although disruptive behavior was more recurrent in children with low SES with respect to their peers with high SES, we cannot assert that behaviors related to aggressiveness belong to a certain socioeconomic context. It could be claimed that stressful events in the life of a child such as socioeconomic deprivation and the resulting stress in the parental figures (which influences the type of upbringing) can trigger the apparition of dysfunctional behavior. On the other hand, we observed that 40 % of the children showed behavioral inhibition. Inhibited children with low SES showed fewer social skills with respect to their peers with high SES, although these differences were not statistically significant. If we bear in mind that behavioral inhibition is characterized by fear and isolation in the face of new situations, the child’s social deficits concerning peer relations or relations with adults increase his/her anxiety symptoms.

It should be noted that in both cases we observed that the level of social skills was lower than that of their peers without this symptomatology, which allows us to infer that the presence of these abilities acted as protective resources against behavior problems, preventing the apparition of psychopathological disorders.

4 Is It Possible to Modify Social Behavior?

According to Del Prette and Del Prette (2008), one of the basic characteristics of social skills is their acquired character. This implies the possibility of increasing the procedural knowledge of how to behave in social situations and how to respond to the multiple demands of the different contexts in which a person acts. In turn, if social behaviors are learned, they can be modified. Children and adolescent intervention programs operating in the fields of prevention and promotion have been designed on the basis of the concept of the modifiability of behavior.

School and family as well as access to other membership groups are privileged environments for the learning of social skills, if these contexts can provide the child with the positive experiences required for the acquisition of social behavior. We learn from what we see, from what we experience (our own actions) and from the feedback obtained from interpersonal relations; we also learn social behavior from the media as well as from the use of cultural symbols. In conclusion, context, in its multiple meanings (maternal and paternal characteristics, upbringing, and access to material goods such as television or internet, among others) is decisively related to the way in which salutogenic or dysfunctional social skills are learned and practiced.

For Kelly (1987), interventions in interpersonal capacities are functionally justified on the basis of the principles of the theory of social learning. These differ from other psychotherapeutic interventions mainly in their purpose, since they act independently of the etiology of the social deficit, placing emphasis on the positive aspects of the subject and developing skills such as alternative social behavior. Although intervention programs have had different theoretical supports such as humanistic, systemic, cognitive or behavioral theories, the most representative authors (Caballo, 2005; Gil Rodríguez, León Rubio, & Jarana Expósito, 1995) point out that cognitive-behavioral techniques prevail in intervention programs. Techniques such as instructions, modeling, behavior rehearsal and reinforcement, among others, are used in individual or group designs.

Different studies have demonstrated the efficacy of the teaching of social skills to children (Garaigordobil Landazabal, 2001; Michelson, Sugai, Wood, & Kazdin, 1987; Monjas Casares, 2002, 2004). In Latin America, empirical experiences revealed the existence of consolidated and prolific research groups, especially on the subject of childhood. Such is the case of the above mentioned group of Del Prette & Del Prette in Brazil and of other teams in Argentina. For instance, Wainstein and Baeza (2005) studied interpersonal relations in the classroom with a methodology of intervention-action in order to modify dysfunctional teacher-student and student-student relations. Ricahud de Minzi and his team worked on the generation of interpersonal relationships and positive emotions in children in Santa Fe and Entre Rios. After applying the ‘Intervention program to strengthen affective, cognitive and linguistic resources in children at risk because of extreme poverty’ [Programa de intervención para fortalecer los recursos afectivos, cognitivos y lingüísticos en niños en riesgo por extrema pobreza], the team found that interventions showed a remarkable increase in the use of functional coping strategies together with increased impulse control, inhibitory control, social skills, planning and meta-cognition (Richaud de Minzi, 2007). In Mendoza, Ison (2009) worked with intervention programs on attention deficit and cognitive abilities that play a role in the solution of interpersonal problems in schoolchildren.

4.1 Intervention Experiences with Children in Tucumán

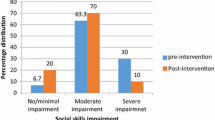

In 2010–2011 an intervention program for the development of assertive social skills in children in contexts of poverty was implemented in San Miguel de Tucumán (Argentina). In the pre- and post-test stage, the Socialization Battery BAS (Silva Moreno & Martorell Pallás,1983, 2001) was applied in its three versions: BAS-1 for teachers, BAS-2 for parents and BAS-3 for teenagers. This technique evaluates facilitating (consideration toward others, self control and leadership) and inhibiting dimensions (withdrawal and social anxiety) of socialization. The self report version was adapted for children under 11 years of age from local samples (Lacunza, 2010; Smulovitz, 2011). Besides, a tool (CABS) concerning assertive, aggressive and inhibited behavior was applied to the participants.

The program included 88 children between 9 and 13 years of age who attended the 4th grade (morning shift) in a public school in San Miguel de Tucumán (the capital city, with approximately 600,000 inhabitants), belonging to an urban poverty context. The clinical group was formed by divisions A and B (59 children) while the control group was division C (29 children). The groups were selected from a population of 687 students enrolled in that school shift. The intervention program was applied to the experimental group during ten group sessions of 60 min each with a weekly frequency. The children in the control group participated in five play-shops focused on Children’s Rights, once every 2 weeks and with an approximate duration of 60 min.

The intervention was based on the social interaction skills teaching program (PEHIS) of Monjas Casares (2002), with an active participative methodology. Three social skills were practiced using the techniques of modeling, practice and reinforcement. Each session included group and/or individual play activities with a routine of presentation, play activity and a final discussion. The abilities, techniques and play activities developed are presented in Table 12.1.

Informant reports (BAS-1 and 2) were applied exclusively during the pre-test stage. The teachers completed the BAS only of those students with aggressive behaviors. On the other hand, parental attendance to the BAS-2 was low. In those cases, administration was individual in view of the difficulties in reading and comprehension. The results showed divergences, since the teachers described male students as more aggressive and anxious than females, while parents described them as more extrovert in social relations, although also aggressive and undisciplined. No statistically significant associations were found between the two tools, with the exception of a statistically negative association between Leadership (BAS-1) and Withdrawal (BAS-2) (r = −.963, p = .037), that is to say, that students described by their teachers as leaders rated very low in social withdrawal and introversion according to their parents.

It should be noted that the intervention stage had different effects. The clinical group showed aggressive behaviors during the pre-test stage while during the post-test stage an increase in self control to establish social relations was observed, which represents compliance with social norms and rules (t = −3.3, gl = 25, p = .003). However, there was also an increase in inhibited behaviors with respect to those identified during the pre-test stage (t = −3.37, gl = 25, p = .002). The children in the control group showed lower leadership during the post-test evaluation (t = 2.74, gl = 13, p = .017) and lower use of assertive behaviors (t = 2.45, gl = 5, p = .057). Besides, we observed a greater choice of aggressive behaviors with respect to the pre-test stage.

The intervention process included training workshops for teachers so that they would be able to include activities related to the promotion of assertive social skills in the school curriculum. As the teaching staff was the same during the following school year, the children, together with their teachers, continued to perform activities related to these types of skills. That is why they were evaluated again 12 months after the end of the intervention. Although no statistical differences were found between both groups, the clinical group was found to show greater consideration toward their peers in social relations than the control groups, although with increased inhibition behaviors (F (1, 29) = 14.96, p = .001). The children in the control group showed more aggressive behaviors than the clinical group (F (1, 26) = 19.13, p = .000). It should be noted that the decrease in cases in this new evaluation was mainly due to the mobility in enrollment, so that participant repetition and dropout, which are indicators of the educational inequity still found in contexts of structural poverty, should be borne in mind for the interpretation of data.

This empirical experience shows the increase in assertive social skills in children with deficits, particularly in those in the clinical group, which supports the assumption of the present study with respect to the modification of social behavior. Besides, it suggests that the school context is a very important place for the learning of social skills. The school, as a socializing institution, is responsible for the teaching of social skills to students to promote social competence and especially living with others. Besides, the teaching-learning process has as a basic recourse interpersonal relations and interpersonal communication, social skills being an essential resource. We also tried to show how the end of an intervention influences the progress made by the children, as evidenced by an increase in withdrawal behaviors in the clinical group and in aggressiveness in the control group. The evaluation-intervention method described in the present study is in line with the theory and the empirical evidence of other investigations, although it is necessary to consider the limitations of the results presented here.

5 Final Considerations

The study of social behavior is relevant for the promotion of the psychological health of children and teenagers. Over the last decades, it has been demonstrated that assertive social skills are a health protecting factor, since they promote healthy child development and prevent the apparition of psychopathological disorders. Authors agree that an assertive individual is one who knows and controls his feelings, can interpret the states of mind of others and is able to operate in his environment, optimizing his life quality. Although the concept of social skills has been used in different theoretical models, its influence on well-being allows us to associate it with the salutogenic approach, especially in the case of those abilities that enable satisfactory relations, relations of trust, belonging, acceptability, cooperation and collaboration.

These abilities allow positive survival, especially in a complex society in which violence and ill being prevail. Bearing in mind that social skills are the basis for mediation strategies, conflict resolution and team work, among other aspects, they contribute not only to adequate interpersonal functioning but also to adjustment and adaptation in childhood and in adult life.

Social skills develop from learning experiences that strengthen assertive behaviors and that, consequently, reinforce the positive perception of the subject with respect to his social competence. As mentioned above, the school environment is a valid and transcendental context for the application of intervention programs that, as Garaigordobil Landazabal (2008) stated, promote cooperative over competitive behavior.

From a positive perspective, social skills are protective resources and promoters of well-being. Although there is a prevalence of studies on social deficits and their effects on different adaptive areas of the child, empirical evidence is also important with respect to the positive role of social interactions in the promotion of positive development and psychological strengths. Seligman (2003) stated that social resources are a precocious power that can act as a barrier against the weaknesses and uncertainties of life.

References

Achenbach, T., McConaughy, S., & Howell, C. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 213–232.

Amesty, E., & Clinton, A. (2009). Adaptación Cultural de un Programa de Prevención a Nivel Preescolar. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 43(1), 106–113.

Bandeira, M., Rocha, S. S., Freitas, L. C., Del Prette, Z. A., & Del Prette, A. (2006). Habilidades sociais e variáveis sociodemográficas em estudantes do ensino fundamental. Psicologia em Estudo, 11(3), 541–549.

Bandura, A. (1987). Pensamiento y Acción. Barcelona, Spain: Martínez Roca.

Bellack, A. S., & Morrison, R. L. (1982). Interpersonal dysfunction. In A. S. Bellack, M. Hersen & A. E. Kazdin (Comps.), International handbook of behavior modification and therapy (pp. 717–748). New York: Plenum Press.

Buck, R. (1991). Temperament, social skills, and the communication of emotion: A developmental-interactionist perspective. In D. Gilbert & J. J. Conley (Eds.), Personality, social skills, and psychopathology: An individual differences approach (pp. 85–106). New York: Plenum.

Caballo, V. (2005). Manual de Evaluación y entrenamiento de las habilidades sociales (6° Edición). Madrid, Spain: Siglo XXI Editores.

Campo Ternera, L., & Martinez de Biava, Y. (2009). Habilidades sociales en estudiantes de Psicología de una universidad privada de la Costa Caribe Colombiana. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología: Ciencia y Tecnología, 2(1), 39–51.

Cia, F., Pamplin, R. C. O., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2006). Comunicação e participação pais-filhos: Correlação com habilidades sociais e problemas de comportamento dos filhos. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 16, 395–406.

Curran, J. P. (1979). Pandora’s box reopened? The assessment of social skills. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 1, 55–71.

Del Prette, Z., & Del Prette, A. (2008). Um sistema de categorías de habilidades sociais educativas. Paidéia, 18(41), 517–530.

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2003). Luz, câmera, acao: desenvovendo um sistema multimidia para avaliaçao de habilidades sociais em crianças. Avaliaçao Psicologica, 2(2), 155–164.

Diaz-Sibaja, M., Trujillo, A., & Peris-Mencheta, L. (2007). Hospital de día infanto-juvenil: Programas de tratamiento. Revista de Psiquiatría y Psicología del niño y del adolescente, 7(1), 80–99.

Dunn, J. (1988). Los comienzos de la comprensión social. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Nueva Visión.

Elliott, S., DiPerna, J., Mroch, A., & Lang, S. (2004). Prevalence and patterns of academic enabling behaviors: An analysis of teachers’ and students’ ratings for a national sample of students. School Psychology Review, 33(2), 302–309.

Ferreyra, Y., & Reyes Benitez, P. (2011). Programa de Intervención en Habilidades Sociales para reducir los niveles de acoso escolar entre pares o bullying. AJAYU, 9(2), 264–283.

Forns, I., & Santacana, M. (1993). Evaluación psicológica infantil. Barcelona, Spain: Barcanova.

Furnham, A. (1979). Assertiveness in three cultures: Multidimensionality and cultural differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 522–527.

Garaigordobil Landazabal, M. (2001). Intervención con adolescentes: impacto de un programa en la asertividad y en las estrategias cognitivas de afrontamiento de situaciones sociales. Psicología conductual: Revista internacional de Psicología Clínica y de la Salud, 9(2), 221–246.

Garaigordobil Landazabal, M. (2008). Intervención psicológica con adolescentes: un programa para el desarrollo de la personalidad y la educación en derechos humanos. Madrid, Spain: Pirámide.

García Nuñez del Arco, C. (2005). Habilidades sociales, clima social familiar y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Liberabit, 11, 63–74.

Gil Rodríguez, F., León Rubio, J., & Jarana Expósito, L. (1995). Habilidades sociales y salud. Madrid, Spain: Pirámide.

Goncalves, E., & Murta, S. (2008). Avaliação dos efeitos de uma modalidade de treinamento de habilidades sociais para crianças. Psicologia: Reflexão e Critica, 21(3), 430–436.

Greco, C., & Ison, M. (2009). Solución de problemas interpersonales en la infancia: modificación del test EVHACOSPI. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 18(2), 121–134.

Gresham, F. (1988). Social skills: Conceptual and applied aspects of assessment, training and social validation. In J. Witt, S. Elliott & F. Gresham (Comps.), Handbook of behavior therapy in education (pp. 523–546). New York: Plenum Press.

Gresham, F., & Rechly, D. (1988). Issues in the conceptualization, classification and assessment of social skills in the mildly handicapped. In T. Kratochwill (Ed.), Advances in school psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 203–246). Hillsdale, NY: Erlbaum.

Grietens, H., Van Assche, V., Prinzie, P., Gadeyne, E., Ghesquière, P., Hellinckx, W., et al. (2004). A comparison of mothers’, fathers’ and teachers’ reports on problem behavior in 5-to-6-year-old children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 137–146.

Hecht, H., Genzwurker, S., Helle, M., & Calker, D. (2005). Social functioning and personality of subjects at familiar risk for affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 84(1), 33–42.

Hecht, H., & Wittchen, H. (1988). The frequency of social dysfunction in a general population sample and in patients with mental disorders: A comparison using the social interview schedule (SIS). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 23, 17–29.

Inglés, C. J., Benavides, G., Redondo, J., García-Fernández, J. M., Ruiz-Esteban, C., Estévez, C., et al. (2009). Conducta prosocial y rendimiento académico en estudiantes españoles de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Anales de Psicología, 25, 93–101.

Ipiña, M., Molina, L., & Reyna, C. (2010). Estructura factorial y consistencia interna de la Escala MESSY (versión docente) en una muestra de niños Argentinos. Suma Psicológica, 17(2), 151–161.

Ipiña, M., Molina, L., & Reyna, C. (2011). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala MESSY (versión autoinforme) en niños argentinos. Revista de Psicología, 29(2), 245–264.

Isaza Valencia, L., & Henao López, G. (2011). Relaciones entre el clima social familiar y el desempeño en habilidades sociales en niños y niñas entre dos y tres años de edad. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 14(1), 19–30.

Ison, M. (2009). Abordaje psicoeducativo para estimular la atención y las habilidades interpersonales en escolares argentinos. Persona, 12, 29–51.

Ison, M., & Fachinelli, C. (1993). Guía de Observación Comportamental para niños. Interdisciplinaria, 12(1), 11–21.

Ison, M., & Morelato, G. (2008). Habilidades sociocognitivas en niños con conductas disruptivas y víctimas de maltrato. Universitas Psychologica, 7(2), 357–367.

Kaye, K. (1982). The mental and social life of babies. London: Methuen.

Kelly, J. (1987). Entrenamiento de las habilidades sociales. Bilbao, Spain: D.D.B.

Kirchner, T. (1997). Evaluación del desarrollo psicosocial. In G. Buela Casal & C. Sierra (Dirs), Manual de Evaluación Psicológica: Fundamentos, Técnicas y Aplicaciones (pp. 773–778). Madrid, España: Siglo XXI.

Lacunza, A. B. (2010, November). Habilidades sociales y comportamiento prosocial en los niños. Propuestas de evaluación e intervención. Work presented at the 5th Encuentro Iberoamericano de Psicología Positiva, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Lacunza, A. B. (2012, June). Habilidades sociales en niños del norte argentino: recursos para su evaluación y promoción. Work presented at the 4th Congreso Regional, Sociedad Interamericana de Psicología (SIP), Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

Lacunza, A. B., & Contini, N. (2009). Las habilidades sociales en niños preescolares en contextos de pobreza. Ciencias Psicológicas, 3(1), 57–66.

Martínez, J., Cuevas, J., Arbeláez, C., & Franco, A. (2008). Agresividad en los escolares y su relación con las normas familiares. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 3, 365–377.

Meichenbaum, D., Butler, L., & Grudson, L. (1981). Toward a conceptual model of social competence. In J. Wine & M. Smye (Comps.), Social competence (pp. 36–59). New York: Guilford Press.

Michelson, L., Sugai, D., Wood, R., & Kazdin, A. (1987). Las habilidades sociales en la infancia: Evaluación y tratamiento. Barcelona, Spain: Martínez Roca.

Ministerio de Salud. (2010). Estimación de la población afecta de 15 años y más por trastornos mentales y del comportamiento en Argentina. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ministerio de la Salud-Presidencia de la Nación. Retrieved from http://www.msal.gov.ar/saludmental/images/stories/info-equipos/pdf/1-estimacion-de-la-poblacion-afectada.pdf

Mischell, W. (1968). Personality assessment. New York: Wiley.

Molina, R. M., & Del Prette, A. (2007). Mudança no status sociométrico negativo de alunos com dificuldades de aprendizagem. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 11(2), 299–310.

Monjas Casares, M. (2002). Programa de enseñanza de habilidades de interacción social (PEHIS) para niños y niñas en edad escolar. Madrid, Spain: CEPE.

Monjas Casares, M. (2004). Ni sumisas ni dominantes. Los estilos de relación interpersonal en la infancia y en la adolescencia. Memoria de Investigación, Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica, Valladolid, Spain. Retrieved from http://www.inmujer.migualdad.es/mujer/mujeres/estud_inves/672.pdf

Monjas Casares, M., Arias, B., & Verdugo, M. (1991). Desarrollo de un Código de Observación para evaluar la Interacción Social en alumnos de primaria (COIS). Work presented at the 2th Congreso de Evaluación Psicológica, Barcelona, Spain.

Murphy, G., Murphy, L., & Newcomb, T. (1937). Experimental social psychology: An interpretation of research upon the socialization of the individual. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Perez Fernandez, J., & Garaigordobil Landazabal, M. (2004). Relaciones de la socialización con inteligencia, autoconcepto y otros rasgos de la personalidad en niños de 6 años. Apuntes de Psicología, 22(2), 153–169.

Pichardo, M., García, T., Justicia, F., & Llanos, C. (2008). Efectos de un programa de intervención para la mejora de la competencia social en niños de educación primaria en Bolivia. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8(3), 441–452.

Reyna, C., & Brussino, S. (2009). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Comportamiento Preescolar y Jardín Infantil en una muestra de niños Argentinos de 3 a 7 Años. Psykhe, 18(2), 127–140.

Reyna, C., & Brussino, S. (2011). Evaluación de las habilidades sociales infantiles en Latinoamerica. Psicología em Estudo, Maringá, 16(3), 359–367.

Richaud de Minzi, M. (2007). Fortalecimiento de recursos cognitivos, afectivos, sociales y lingüísticos en niñez en riesgo ambiental por pobreza: un programa de intervención. In M. Richaud & M. Ison (Eds.), Avances en investigación en ciencias del comportamiento en Argentina (Vol. 1, pp. 147–176). Mendoza, Argentina: Editorial de la Universidad del Aconcagua.

Rubin, K. H., Dwyer, K. M., Booth-LaForce, C., Kim, A. H., Burgess, K. B., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (2004). Attachment, friendship, and psychological functioning in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 326–356.

Sanz, J., Gil, F., & García-Vera, M. P. (1998). Evaluación de las habilidades sociales. In F. Gil & J. M. León (Eds.), Entrenamiento en habilidades sociales: Teoría, evaluación y aplicaciones (pp. 25–62). Madrid, Spain: Síntesis.

Schulz, A. (2008). Validación de un sistema de evaluación de las habilidades sociales en niños argentinos por medio de informantes clave. Resultados preliminares (Informe final del Proyecto de Investigación 26/07 de la Facultad de Humanidades, Educación y Ciencias Sociales). Libertador San Martín, Argentina: Universidad Adventista del Plata.

Segrin, C., & Taylor, M. (2007). Positive interpersonal relationships mediate the association between social skills and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 637–646.

Seligman, M. (2003). La auténtica felicidad. Barcelona, Spain: Javier Vergara Editor.

Semrud-Clikerman, M. (2007). Social competence in children. New York: Springer.

Sendín, M. C. (2000). Diagnóstico psicológico: Bases conceptuales y guía práctica en los contextos clínico y educativo. Madrid, Spain: Psimática.

Silva Moreno, F., & Martorell Pallás, M. (1983). BAS 1–2 Batería de Socialización (para profesores y padres): Manual. Madrid, Spain: TEA Ediciones.

Silva Moreno, F., & Martorell Pallás, M. C. (2001). Batería de Socialización (BAS-3). Madrid, Spain: TEA.

Smulovitz, A. (2011). Validación de la Escala de Socialización BAS-3 en niños de 9 y 10 años de Concepción (Prov. De Tucumán). Unpublished thesis, Centro Universitario Concepción, Tucumán, Argentina.

Wainstein, M., & Baeza, S. (2005, August). Efecto de las intervenciones con un modelo de resolución de problemas y desarrollo de habilidades sociales sobre la funcionalidad de cales escolares. Actas del XII Jornadas de Investigación, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Williams, H. (1935). A factor analysis of Berne’s social behavior in young children. Journal of Experimental Education, 4, 142–146.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lacunza, A.B. (2014). Social Skills of Children in Vulnerable Conditions in Northern Argentina. In: Castro Solano, A. (eds) Positive Psychology in Latin America. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology, vol 10. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9035-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9034-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9035-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)