Abstract

The concept of wisdom has long defied easy definition and operationalization, although many scholars agree that one essential feature is its paradoxical nature. There is also a growing consensus that wisdom includes a combination of reflective, cognitive, and affective dimensions. In this chapter, we elaborate paradoxical aspects of the concept of wisdom by illuminating how divergent facets in its three dimensions come together. The paradoxes discussed are (1) “I know that I do not know,” (2) a will-not-to-will and an act of nonaction, (3) loss is gain, and (4) liberation through the acceptance of limitations in the reflective dimension; (1) wise judgment in the face of uncertainty, (2) the foolishness of the wise and the wisdom of fools, and (3) wisdom is timeless and universal yet relative and changing in the cognitive dimension; and (1) self-development through selflessness, (2) involvement through detachment, and (3) change through acceptance in the affective dimension. We suggest that people who follow the paradoxical path to wisdom ultimately will gain liberation, truth, and a sense of unlimited love. Narratives of the life of Buddha are used to illustrate the individual paradoxes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Although wisdom occupies a prominent place in ancient religious traditions and philosophies of human development (Birren & Svensson, 2005; Jeste & Vahia, 2008; Osbeck & Robinson, 2005), modern scientific inquiries into this subject have mostly ignored the concept (Blanchard-Fields & Norris, 1995; Chandler & Holliday, 1990). Only recently have a number of contemporary investigators begun to apply the concept of wisdom to the study of human growth (e.g., Ardelt, 2000a, 2000b, 2008b; Baltes & Freund, 2003; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Clayton & Birren, 1980; Dittmann-Kohli & Baltes, 1990; Helson & Srivastava, 2002; Sternberg, 1998). However, despite numerous attempts to refine the concept of wisdom, a uniform definition does not yet exist (Ardelt & Oh, 2010; Baltes & Smith, 2008; Kramer, 1990). It still holds true that “…wisdom as a concept remains wonderful and wondrous but not very clear” (Taranto, 1989, p. 2).

One reason for the difficulties in defining wisdom might be that the concept invites contradictory emphases (Moody, 1986). In his book, Wisdom: From Philosophy to Neuroscience, Stephen S. Hall (2010, p. 11) pointed out the inherent contradictions of wisdom:

Wisdom is based upon knowledge, but part of the physics of wisdom is shaped by uncertainty. Action is important, but so is judicious inaction. Emotion is central to wisdom, yet emotional detachment is indispensable. A wise act in one context may be sheer folly in another.

The goal of this chapter is to elaborate varied dimensions of the concept of wisdom by highlighting how the realms of reflection, cognition, and affection fit together. Although a generally accepted definition of wisdom has not been developed, there is a growing consensus among philosophers, theologians, social scientists, and lay people that, at minimum, wisdom evolves in reflective, cognitive, and affective dimensions (e.g., Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Ardelt, 2011b; Ardelt & Oh, 2010; Jeste et al., 2010; Kekes, 1995; Manheimer, 1992; Meeks & Jeste, 2009; Sternberg & Jordan, 2005).

The reflective dimension of wisdom entails the ability to look at phenomena and events from multiple perspectives without trying to deny any unpleasant truths or to blame other people or circumstances for one’s own situation. A person’s subjectivity and projections, particularly the tendency to blame other people and circumstances for failures and to attribute successes to one’s own abilities rather than judging phenomena and events in an objective manner (Bradley, 1978; Sherwood, 1981), are a major obstacle to this endeavor. Self-examination and reflective thinking are required if one is to become aware and ultimately transcend one’s subjectivity and projections and see through illusions (Kekes, 1995; Kramer, 2000; Levitt, 1999; McKee & Barber, 1999; Sternberg, 1998). Reflective and self-reflective thinking leads individuals to discover the deeper causes of phenomena and events and understand the complex and sometimes contradictory nature of human behavior (Clayton, 1982; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Labouvie-Vief, 1990; Staudinger, Dörner, & Mickler, 2005). The cognitive dimension of wisdom refers to an understanding of the intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of life and a desire to know the truth about the significance and deeper meaning of phenomena and events (Ardelt, 2000b; Blanchard-Fields & Norris, 1995; Kekes, 1983; Osbeck & Robinson, 2005). A deeper insight into one’s own and others’ motives and behavior, in turn, tends to reduce one’s self-centeredness and to increase sympathetic and compassionate love for others (Ardelt, 2000b; Clayton & Birren, 1980; Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2005; Kramer, 1990; Levitt, 1999; Orwoll & Achenbaum, 1993), which characterizes the affective dimension of wisdom.

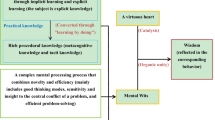

We propose that the development of wisdom entails an iterative process that ultimately transforms the individual (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Hall, 2010; Kekes, 1983; Moody, 1986). The seeker of wisdom will encounter a number of paradoxes that cannot be resolved, such as Socrates’ realization “I know that I do not know.” Rather, the gradual acceptance of these paradoxes will lead a person to the deepest essence of wisdom: liberation, truth, and love (see Fig. 1). We illustrate that process through respondents’ quotes from previous qualitative studies on wisdom and the life stories of Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Buddha after his enlightenment experience (see also Takahashi, 2012). Although we know that many stories surrounding his persona are myths and legends rather than historical facts, there seems to be a consensus that Siddhartha Gautama was indeed a historical figure (Armstrong, 2001; Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Ikeda, 1976; Nakamura, 1977; Thomas, 1949). Yet, for the purpose of this chapter, the historical facts of the stories are less important than the lessons that the stories convey in illustrating the paradoxical nature of wisdom.

The Paradoxical Process of Growing Wiser

Reflective Dimension: Liberation

The reflective wisdom dimension refers to self-examination, self-awareness, and the ability to look at phenomena and events from different perspectives to see through illusions and projections and discover what lies beyond surface appearances (Ardelt, 2000b; Kekes, 1995; Levitt, 1999; McKee & Barber, 1999; Orwoll & Perlmutter, 1990). Yet, the most prominent paradox of wisdom is that wise people know that they do not know, which prompts them to search for an even deeper truth. Self-examination, self-awareness, and self-reflection require a will-not-to-will and an act of nonaction—that is, a will to engage in those practices in order to observe objectively rather than to act with the purpose of achieving a certain goal (Hart, 1987; Pascual-Leone, 1990). Self-reflective unbiased observations enable people to discover the deeper causes of phenomena and events and to become aware, accept, and ultimately transcend their subjectivity and projections (Clayton, 1982; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Kramer, 1990). The loss of subjectivity and projections, in turn, results in greater wisdom through a reduction in self-centeredness. Yet, human limitations, such as subjectivity, projections, and self-centeredness, can only be transcended through their acceptance.

I Know that I Do Not Know

A person in search of knowledge and truth will soon be confronted with a major paradox: the more one knows, the more one knows that one does not know. In fact, the awareness of not knowing is the result of knowledge, not the lack of it. Wise persons know that there are multiple ways to perceive phenomena and events (Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Kramer, 1990; Taranto, 1989). Each newly gained perspective allows them to discern a path ahead, intersected by many more avenues as yet unexplored. Arlin (1990, p. 230) summarized this paradox in the following statement:

Knowing what one does not know can be represented by the questions one asks, the doubts one has, and the ambiguities one tolerates. This type of knowing is the gift of one who has thought deeply in a domain and has a substantial knowledge based within that domain.

Hence, wise people know that they most likely will never grasp truth in its entirety no matter how hard they might try, although they appear knowledgeable and experienced to others (Arlin, 1990; Hall, 2010; Kitchener & Brenner, 1990; Sternberg, 2005). For example, in a qualitative study that asked college students to compare the characteristics of knowledgeable/intelligent persons with those of wise individuals (Ardelt, 2008a, pp. 98–99), one student wrote

Now when I think of a wise individual I think of Yoda from the movie Star Wars. This type of character is usually an elder being.… They have knowledge and intelligence though not only by studying it, but they have experienced it as well.… They have the answer to every question you ask and possibly even put it in a way that makes total sense to you. When this person tells you something you say “aha”. You feel and should feel that it’s an honor that you can meet one of these types. They are very understanding of the youth and … they are very patient.… They just know what to do, when to do it, and how it should be done. What makes the wise great is that they don’t ever think they know it all. The wise will continue to grow even more than you could imagine.

The acceptance of that paradox implies an acceptance of human limitations. This, in turn, indicates the realization of an important truth and, hence, a significant step toward wisdom.

An illustration of this paradox is the early life of Siddhartha Gautama, before he became the Buddha. Siddhartha Gautama was born somewhere between 563 and 463 B.C.E. (the exact birth date is not clear) in the foothills of the Himalayas (southern Nepal) as the son of Shudhodana, the king of the Shakyas (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Kohn, 1994; Nakamura, 1977; Ñanamoli, 2001). As told in Nidāna Kathā, seers prophesied that he would either become a great monarch or, if he renounced the worldly life and followed the spiritual path, attain the final spiritual goal, enlightenment, which means the end of all suffering and the end of the circle of birth and rebirth (Armstrong, 2001; Hakeda & De Bary, 1969; Mitchell, 1989; Ñanamoli, 2001). Hearing those prophecies, King Shudhodana tried everything to shelter his son from the harsher realities of life and to provide him with all the royal luxuries that he could offer. He hoped that a life of luxury would make Siddhartha more inclined to pursue the worldly rather than the spiritual path so that the first rather than the second prophecy would be fulfilled. As the Buddha later told his followers,

I was delicate, O monks, extremely delicate, excessively delicate. In my father’s dwelling lotus-pools had been made, in one, blue lotuses, in another red, in another white, all for my sake. I used no sandalwood that was not of Benares, my dress was of Benares cloth, my tunic, my under-robe, and cloak. Night and day a white parasol was held over me so that I should not be touched by cold or heat, by dust or weeds or dew. (Anguttara-nikāya, i 145, as cited in Thomas, 1949, p. 47)

Siddhartha lived a sheltered existence, but King Shudhodana could not prevent his son from seeing old age, illness, and death (Nakamura, 1977; Ñanamoli, 2001; Thomas, 1949). Although those experiences expanded Siddhartha’s knowledge of life, he simultaneously realized how little he knew about the meaning of existence and the reason for life’s sufferings, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities. This insight prompted him to search for the path of liberation from all suffering.

A Will-Not-to-Will and an Act of Nonaction

Since ultimate wisdom is an ideal state that is virtually impossible to obtain, persons who are very eager to become wise might despair if they fail to succeed, resulting in an unbalanced mind, which makes unbiased self-examination, self-awareness, and self-reflection even more difficult (Hart, 1987). Yet, individuals in pursuit of wisdom need a strong will to persist in order to transcend their subjectivity and projections. Without that determination, it would be impossible to overcome obstacles or to endure setbacks (Kramer, 1990). However, it is not a self-centered will but rather a “will-not-to-will” (Pascual-Leone, 1990) that fosters the acquisition of wisdom. Wise persons do not try to impose their own will on the world, not even their will to grow wiser. They use their will to continue on the path to wisdom despite the difficulty of the task.

Growth in wisdom is primarily achieved through an act of nonaction: to observe and accept reality as it is, including the reality that ultimate wisdom is virtually impossible to obtain (Hall, 2010). An individual in search of wisdom needs to learn to accept the experience of the present moment in its totality without reacting either with craving or aversion, not even a craving for more wisdom or an aversion toward ignorance (Hart, 1987). By mindfully observing and accepting the present moment, what Tolle (2004) called The Power of NOW, one gains insight into the true nature of things including one’s own self and, thereby, grows in wisdom. For example, in a study on age differences in wisdom (Ardelt, 2010, p. 202), an older woman with relatively high wisdom scores explained that only after accepting the fact that her sister was an alcoholic was she able to grow psychologically.

[O]ver a period of years [I] have really gotten to accepting the situation [with the sister] and accepting her as, you know, if it’s her choice, if she wants to live that way, that’s her problem, not mine. I can’t do anything about it. So that’s kind of the best thing I have done actually [in a] lifetime, finally started growing up.… It felt like almost if it hadn’t been for my sister, I never would have gotten there. So, it turned out to be a really good thing.

Life experiences by themselves are not enough to gain wisdom. Individuals first have to accept an experience and the life lesson that it entails before they can grow in wisdom (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Ardelt, 2000b, 2005). This does not mean, however, that a wise person is doomed to a life of nonaction. On the contrary, people whose behavior is not determined by cravings or aversions and who can face the reality of the present moment are truly free to act wisely—that is, in a way that is optimal for themselves and others instead of merely reacting to a subjectively perceived situation (Hart, 1987). For example, in a qualitative study on how wise people cope with crises and obstacles in their lives (Ardelt, 2005, p. 12), a wise older man made it clear that to act freely, one first needs to reflect on, accept, and take responsibility for one’s emotions.

I’ve had as much bad things to happen as good things, but I’ve never allowed any outside force to take possession of my being.… Every time something happens, I say where does that feeling come from? If it comes from within you, then you need to handle it. You can handle it. I can’t make you angry. You get angry. I can’t make you embarrassed. You get embarrassed. (laughing) … I mean, it’s silly, but you think of it, if it is a feeling that comes from within, I am responsible to control it.

In contrast to most individuals, wise persons do not simply react to their projections of outside forces and, therefore, are able to weigh the pros and cons of a particular course of action in an objective manner. However, to reach such a state of objectivity and wisdom, one first needs to develop a calm and balanced mind through the practice of nonaction or pure reflection without reaction (Hall, 2010).

For example, Siddhartha Gautama developed a strong will to find liberation from human suffering after witnessing old age, sickness, and death (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001). At the age of 29, after his son, who would give his father a potential heir to the throne, was born, he decided to abandon the wealth, power, comfort, and luxury of a royal existence to become a homeless monk in search of enlightenment. Because Siddhartha’s family was affluent, he knew that his wife and son would be materially secure even without his presence. In fact, a man abandoning his family to become a spiritual seeker was not unusual during Buddha’s time, but according to the Kautilīya-Arthasāśtra (Vol. II Chap. I), he had to be wealthy enough to guarantee his wife and children’s livelihood in his absence (Nakamura, 1977).

According to the Mahāsaccaka-Sutta or the Majjhima-Nikāya, Siddhartha first practiced meditation with two spiritual teachers who had reached the highest form of spiritual attainment known at this time. Ālāra Kālāma taught the state called nonexistence or nothingness, because nothing that existed in ordinary experience was comparable to this state (Armstrong, 2001), and Uddaka Rāmaputta taught an even higher state that is variously translated as neither thought nor nonthought, neither perception nor nonperception, or neither consciousness nor nonconsciousness (Armstrong, 2001; Nakamura, 1977; Ñanamoli, 2001; Thomas, 1949). Although Siddhartha attained both of these spiritual states in a relatively short period of time, he felt that they did not bring him liberation from all suffering. Disappointed, he left his teachers. His strong will to find a path to liberation prompted him to engage in various rigorous ascetic practices, such as holding his breath for long periods of time and severe fasting, but none of those techniques led to the eradication of all cravings, aversions, and ignorance. Finally, at the age of 35, Siddhartha remembered a time as a child when he was left alone sitting in the cool shade of a rose apple tree and spontaneously started to meditate.

[Q]uite secluded from sensual desires, secluded from unwholesome things I had entered upon and abode in the first meditation, which is accompanied by thinking and exploring, with happiness and pleasure born of seclusion. I thought: “Might that be the way to enlightenment?” Then, following up that memory, there came the recognition that this was the way to enlightenment. Then I thought: “Why am I afraid of such pleasure? It is pleasure that has nothing to do with sensual desires and unwholesome things.” (Majjhima-Nikāya, 36, as cited in Ñanamoli, 2001, p. 21)

After strengthening his body with food, Siddhartha developed a will-not-to-will and practiced the “middle way”—that is, he neither indulged in sensory pleasures nor tortured his body. He simply observed and accepted the observed reality without reacting to it. Yet, he was determined to meditate until he had attained enlightenment and realized the end of all suffering. Later, Buddha explained the act of pure observation without reactive evaluation as follows:

In your seeing, there should be only seeing; in your hearing nothing but hearing; in your smelling, tasting, touching nothing but smelling, tasting, touching; in your cognizing, nothing but cognizing. When contact occurs through any of the six bases of sensory experience, there should be no valuation, no conditioned perception. Once perception starts evaluating any experience as good or bad, one sees the world in a distorted way because of one’s old blind reactions. In order to free the mind from all conditioning, one must learn to stop evaluating on the basis of past reactions and to be aware, without evaluating and without reacting. (based on Udāna, I. x, story of Bāhiya Dārucīriya, also found in Dhammapada Commentary, VIII. 2 (verse 101); as cited in Hart, 1987, p. 117)

When his underlying conditionings of craving for pleasant sensation, of aversion toward unpleasant sensation, and of ignorance toward neutral sensation are eradicated, the meditator is called one who is totally free of underlying conditionings, who has seen the truth, who has cut off all craving and aversion, who has broken all bondages, who has fully realized the illusory nature of the ego, who has made an end of suffering. (Samyutta Nikāya XXXVI (II). i. 3, Pahāna Sutta, as cited in Hart, 1987, p. 156)

Enlightenment or ultimate wisdom can only be attained through meditative acts of nonaction by cultivating a will-not-to-will.

Loss Is Gain

Wisdom is realized through reflection on experiences, and according to Gadamer (1960), each true experience (i.e., an experience that reveals something new) negates an expectation. Hence, wisdom is gained through failed expectations (Jarvis, 1992) and the loss of illusions, attachments, and aversions (Levenson, Aldwin, & Cupertino, 2001; McKee & Barber, 1999). This might explain why wisdom is often gained through loss and suffering (Ardelt, 2005; Kinnier, Tribbensee, Rose, & Vaughan, 2001; Randall & Kenyon, 2001). Loss and suffering provide the opportunity to see the world and the meaning of life in a new light, which can lead to greater self-knowledge, a reduction in self-centeredness, and stress-related growth (Aldwin, 2007; Aldwin, Levenson, & Kelly, 2009; Glück & Bluck, 2012; Park & Fenster, 2004). For instance, in a qualitative study that explored the pathways to self-transcendence of relatively wise elders (Ardelt, 2008b, p. 227), a woman recounted how her divorce at the age of 32 helped her turn her superficial, pleasure-filled life in a more spiritual and deeper direction.

I was young and full of life and energy, and my energies were always on the dance floor or parties or whatever. I was having a good time. I thought that that was the good time. I had my cigarettes and my beer or whatever, a cocktail, as they call it. If things happened I’d say “Oh Lord, why did this have to happen to me? Oh Lord, take that and don’t let it happen to me.” Now I understand. Things happen to everybody. And some things are supposed to happen to you, because if you don’t have anything happen, you don’t need to pray.… And when God gets ready for you to stop all that foolishness, He’ll stop it. So yes, I’ve learned, and I’ve learned how to pray.

Similarly and as explained in greater detail below, Krsā Gautamī learned through the loss of her infant son and the guidance of Buddha that no human being is sheltered from the pain of death and suffering. The experience prompted her to follow Buddha’s teachings to transcend illusions, attachments, and aversions. She eventually became fully liberated and taught many others the path to the cessation of all suffering (Mitchell, 1989).

However, the negation of expectations does not need to be negative. Subjectivity and projections are the result of selective perception and an unwillingness to give up expectations and assumptions in light of new information (Heller, 1984). Hence, it can be liberating and a source of joy to shed false assumptions, especially if they prevent personal growth (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2005; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Hanna & Ottens, 1995; Levenson et al., 2001). For example, a man who suspects that his wife cheats on him might feel relieved when he discovers that his jealousy is not grounded in his wife’s behavior but in his own misperceptions of reality.

Whereas the loss of false expectations, subjectivity, projections, and illusions results in psychological gain, there is a danger that worldly gain and success might lead to a loss of wisdom. Wisdom is not dependent on worldly success or cleverness (Dittmann-Kohli & Baltes, 1990; Sternberg, 1998) nor is it related to personal power and importance or the mere accumulation of information (Ardelt, 2000b, 2008a). In fact, one of the outstanding characteristics of self-transcendent wise elders was their humility and gratitude (Ardelt, 2008b). A self-centered ego, by contrast, is likely to thwart growth in wisdom, as one student illustrated when comparing a wise person with a knowledgeable/intelligent individual (Ardelt, 2008a, p. 99).

If you compare the Dalai Lama with someone like Donald Trump you’ll find that while Trump’s life basically revolves around his ego, the Dalai Lama has a perfect grasp on his.… Knowledgeable people in general do a lot more speaking than they do listening, when listening is what in fact makes someone wise. To be a listener (or a wise person), you must be able to separate your self from your ego, which is in fact hard to do, and which is exactly what the Dalai Lama has done. Without having an excessive ego or overbearing pride, one can truly open oneself up to learning from others and every event they experience in their lives.

Success might have a detrimental effect on the attainment of wisdom insofar as it causes pride, a sense of self-importance, and the illusion of understanding (Meacham, 1990). For example, one student described a knowledgeable/intelligent individual as follows (Ardelt, 2008a, p. 99):

[T]his person I hold as the most intelligent and knowledgeable individual I know … is the most ambitious, most promising, smartest and most driven person I have ever known, but he lacked wisdom, compassion, and the big picture. He now attends Harvard and serves jail time in the summers.

This does not mean that wise people need to avoid worldly success. Paradoxically, wise people are likely to be successful in their endeavors because they perceive reality more clearly and know how to deal with the vicissitudes of life (Ardelt, 2005). Yet, if worldly success, power, or fame becomes more important than the pursuit of wisdom, self-centeredness and subjectivity will again increase, resulting in a loss of wisdom (Meacham, 1990).

Prince Siddhartha Gautama left his home, family, power, and wealth to become a homeless monk and gain enlightenment. His enlightenment experience illustrates how a loss of subjectivity, projections, self-centeredness, and even pleasure increases wisdom:

Now having taken solid food and gained strength, without sensual desires, without evil ideas I attained and abode in the first trance of joy and pleasure, arising from seclusion and combined with reasoning and investigation. With the ceasing of reasoning and investigation I attained and abode in the second trance of joy and pleasure arising from concentration, with internal serenity and fixing of the mind on one point without reasoning and investigation. With equanimity towards joy and aversion I abode mindful and conscious, and experienced bodily pleasure, what the noble ones describe as “dwelling with equanimity, mindful and happily,” and attained and abode in the third trance. Abandoning pleasure and abandoning pain, even before the disappearance of elation and depression, I attained and abode in the fourth trance, which is without pain and pleasure, and with purity of mindfulness and equanimity. (Majjhima-Nikāya i. 21, as cited in Thomas, 1949, pp. 66–67)

The above-described event occurred in the first part of the night. In the second part of the night, the Buddha examined the laws of karma (cause and effect) and reincarnation, and in the third part of the night, he explored the path to enlightenment and liberation from all suffering, which reverses the law of cause and effect. Buddha finally realized the ultimate truth: the chain of events that causes human suffering and the reversed path to the liberation of suffering:

If ignorance is eradicated and completely ceases, reaction ceases;

if reaction ceases, consciousness ceases;

if consciousness ceases, mind-and-matter cease;

if mind-and-matter cease, the six senses cease;

if the six senses cease, contact ceases;

if contact ceases, sensation ceases;

if sensation ceases, craving and aversion cease;

if craving and aversion cease, attachment ceases;

if attachment ceases, the process of becoming ceases;

if the process of becoming ceases; birth ceases;

if birth ceases, decay and death cease, together with sorrow, lamentation, physical and mental suffering and tribulations.

Thus this entire mass of suffering ceases. (Majjhima-Nikāya, 38, as cited in Hart, 1987, p. 50)

Reflecting his right understanding, the great hermit arose before the world as the Buddha, the Enlightened One. He found self (atman) nowhere, as the fire whose fuel has been exhausted.… For seven days, the Buddha with serene mind contemplated [the Truth that he had attained] and gazed at the Bodhi tree without blinking: “Here on this spot I have fulfilled my cherished goal; I now rest at ease in the dharma of selflessness” (Buddhacarita, as cited in Hakeda & De Bary, 1969, p. 69).

What the Buddha discovered through his enlightenment experience was the complete cause-and-effect chain of existence and how this thread can be reversed to gain liberation from suffering (see also Rosch, 2012). The key for “turning the wheel in the opposite direction” is the development of equanimity and the practice of nonreaction to any sensation that arises, which requires the absolute acceptance of the reality of the present moment (Hart, 1987). Hence, enlightenment entails (1) self-reflection and self-examination, (2) the eradication of ignorance, that is, the loss of all subjective projections and illusions through the complete acceptance of the present moment, and (3) the loss of a sense of self to realize the ultimate truth that lies beyond mind and matter.

Liberation Through the Acceptance of Limitations

The main goal of wisdom, from ancient to modern times, has been the comprehension of human nature with all its paradoxes and contradictions and the understanding of the interrelatedness of all aspects of life and the ultimate causes and consequences of events (Clayton, 1982; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Taranto, 1989). The major obstacles in this pursuit are subjectivity and projections. Perceptions tend to be biased through a filter of subjectivity and cultural and personal projections, which necessarily lead to a distorted truth (Emerson, 2001; Hart, 1987). Self-centeredness prevents individuals from seeing reality “as it is” (Maslow, 1970), that is, to perceive reality without subjective distortions or a “myside bias” (Sternberg, 2012).

The attainment of wisdom requires the transcendence of subjectivity and projections. This, however, can only be accomplished by first becoming aware of one’s subjectivity and projections through the practice of self-examination and self-awareness (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Clayton, 1982; Kekes, 1995; Levitt, 1999). The task requires an unbiased and balanced mind that is open to all kinds of experiences, including the awareness of one’s subjective projections. As Kramer (1990, p. 296) observed, “paradoxically, it is the awareness of one’s subjectivity—or one’s projections—that allows one to begin the task of overcoming that subjectivity.”

If people are able to observe their behavior objectively and with equanimity, they will become aware of their projections and can try to transcend them. However, without an awareness of their subjectivity, they might feel no need to reflect on their behavior. Hence, the question arises how subjective projections initially are recognized. Kramer (1990) suggested that crises and obstacles in people’s lives have the potential to initiate that dialectical process within them. Very often, the resolution of crises and the removal of obstacles necessitate a change in perspective. Sometimes, seeing or listening afresh is instructive. Changes in perception normally require the transcendence of certain projections, which, in turn, tends to cause a decrease in self-centeredness and an increase in maturity and wisdom. For example, a student explained how her uncle grew in wisdom by learning from obstacles in his own life and from others (Ardelt, 2008a, p. 91).

Although my [wise] uncle often talks about times he has failed or done the wrong thing, he has a hopeful spirit about him that he knows he isn’t supposed to know how to do everything in this world correctly, but can provide insight into what he has learned from himself and those around him. He is somewhat quiet in that he notices little things about himself, he is self-observant, but also notices what others do as well.

Not surprisingly, it is quite difficult to overcome all projections. Whereas equanimity and objectivity are necessary to transcend one’s projections, true equanimity and objectivity can only be achieved after all projections are transcended. Furthermore, although people can obtain a broader perspective, human senses are too limited in nature to unveil the ultimate truth behind phenomena and events (Kramer, 1990; Sternberg, 1990b). In general, we are only able to perceive selected slices of reality, although the selection might vary from “narrow-mindedness” to “openness to all kinds of experiences” (Levenson & Crumpler, 1996). With the exception of rare individuals who have attained full enlightenment, such as Buddha, most people in search of wisdom have to accept that they will never be completely wise. Yet, paradoxically, only the acceptance of projections enables a person to pursue their transcendence (Kramer).

Self-centeredness, subjectivity, and projections also prevent people from facing death, which might be considered the ultimate human limitation. Erikson (1964, p. 133) defined wisdom as “…detached concern with life itself in the face of death itself.” A wise person is able to face the human limitations that accompany the aging process, such as social, physical, and mental losses, with equanimity and acceptance rather than despair (Erikson, 1982). Wise individuals are not afraid of death and dying but tend to be content until the very end of life, because they understand and accept life’s limitations (Ardelt, 2003, 2007; Kekes, 1983). Taranto (1989, p. 16) wrote, “…with acceptance, detachment, and humor about failing physical and social potential, aged people may still take charge of their lives and develop a new level of autonomy, because such an attitude makes one impervious to the vicissitudes of life.” For example, one male self-transcendent, wise elder observed (Ardelt, 2008b, p. 226),

When you’re young in life you’re a radical. You’ve got your physical strength, and you depend on that a lot. As you grow older, a heart attack, arthritis, a wreck or something brings you closer to the spiritual. So as the physical gets weaker, the spiritual gets stronger until, I guess, when you’re about my age, you’re right there.

Only someone who can accept the reality of death can truly live (Kekes, 1983). A qualitative study of middle-aged cancer survivors showed when people are aware of the finitude of life, they consider each minute a valuable and precious gift that should not be wasted (Ardelt, Ai, & Eichenberger, 2008). As Kekes (1983, p. 280) declared,

The significance of death is not merely that it puts an end to one’s projects, but also that one’s projects should be selected and pursued in the light of the knowledge that this will happen.… What a wise man knows … is how to construct a pattern that, given the human situation, is likely to lead to a good life.

Paradoxically, only individuals who can fully accept their human limitation, including the realities of the aging process and the finality of life, can really be free to live life to the fullest. For example, through his enlightenment experience, Buddha discovered that whatever arises will eventually cease to exist and that everything is in a constant process of change, including body, mind, and self. Yet, people do not tend to take those limitations into account in their daily lives. Buddha taught that suffering results from the attachment to things that are impermanent, including body, mind, and self. However, by accepting and observing the changing, impermanent nature of everything that exists, attachments gradually lose their strength and the liberation from suffering becomes possible (Hart, 1987; Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001). Hence, liberation requires the acceptance of limitations.

Cognitive Dimension: Truth

The cognitive wisdom dimension represents a deep understanding of the intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of existence (Ardelt, 2000b). Wise persons are able to give sound and sage advice because they take the unpredictability and uncertainty of life into account. Consequently, wise people might sometimes appear foolish. Paradoxically, fools might be able to give sage advice by repeating the timeless and universal truths that wise people have taught and that can be found in books or proverbs, all without truly understanding or benefiting from the advice themselves. Whereas the essence of wisdom is timeless and universal, in its concrete expression it is relative and changing, because it needs to be realized and experienced in a specific context to have any transformative effects.

Wise Judgment in the Face of Uncertainty

Wise persons are aware of the fact that “…uncertainty is ‘the natural habitat of human life’ although the desire to escape uncertainty has been the main engine of human pursuits” (Bauman, 2008, p. 18). Wise individuals, however, possess expertise in dealing with the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of uncertainty (Brugman, 2000). By accepting the limitations of knowledge and the inherent uncertainty of life, the wise are able to give sage advice, especially in the areas of intrapersonal and interpersonal matters (Ardelt, 2008a; Kitchener & Brenner, 1990). Because wise persons perceive phenomena and events from multiple perspectives, they are likely to detect the deeper causes of a problem and how it is related to the larger social context and to a person’s whole life course (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Dittmann-Kohli & Baltes, 1990; Montgomery, Barber, & McKee, 2002). According to Kitchener and Brenner (1990, p. 226), wise people arrive at reflective judgments:

Such judgments reflect a recognition of the limits of personal knowledge, an acknowledgment of the general uncertainty that characterizes human knowing, and a humility about one’s own judgments in the face of such limitations.… Although … [these people] recognize the uncertainty of knowing and the relativity of multiple perspectives, they can overcome this relativity, find the shared meaning, evaluate the alternative interpretations, and develop a synthetic view that offers, at least, a tentative solution for the difficult problem at hand.

Whereas the value of technical and procedural advice varies proportionally with the amount of useful information the advice giver has, wise judgments depend on the advice giver’s acceptance of human limitations and weaknesses, including the negative and contradictory aspects of human nature. Wise people are able to understand and advise others because they understand and have accepted their own limitations and weaknesses. As Weinsheimer (1985, pp. 165–166) explained, “Understanding always involves projecting oneself. What we understand therefore is ourselves, and thus how we understand ourselves has an effect on everything else we understand.” This means that our subjective projections determine our understanding of ourselves, others, and reality. Only by seeing through the illusion of our subjectivity and projections are we able to perceive ourselves, others, and reality in a nonbiased, nonjudgmental, and untainted way and understand that other people struggle with the same subjective projections (Kramer, 1990; McKee & Barber, 1999; Randall & Kenyon, 2001). To overcome our subjective projections, we need to look at ourselves unflinchingly and objectively and acknowledge our shortcomings and contradictions. The acceptance of our human limitations, in turn, decreases our need for projections and the need to defend an idealized image of the self. The resulting reduction in self-centeredness, combined with an understanding of the imperfections of human nature, tends to result in greater compassion and sympathy toward others (Ardelt, 2000b, 2008a; Helson & Srivastava, 2002). Other-centeredness, compassion, and sympathetic empathy are the pillars of sage advice (Montgomery et al., 2002). Indeed, giving wise advice was one of the most prominent characteristics students mentioned when describing a wise person. For example, one student wrote (Ardelt, 2008a, pp. 86–87)

My mother is someone I would describe as wise. I didn’t really start discovering the benefits of having a wise parent until about my late teenage years, when all that “real life stuff” finally started occurring in my life and I needed some guidance, some direction. That’s what my mother always gives me … my mother really goes beyond just looking at things as black and white, right or wrong … for her, there are always many aspects to every lesson I ever grew up learning in my house.

It is important to note that wise persons are not just good problem solvers in a mundane sense. Their problem solving and advice giving is always directed toward personal growth.

There are many stories of how Gautama Buddha gave wise advice to people who sought his help after his enlightenment (see also Ferrari, Weststrate, & Petro, 2012). One famous story, recorded in the Therīgāthā, is about a woman, Krsā Gautamī, who would not accept the death of her infant son (Mitchell, 1989; Thomas, 1949). She carried the dead son in her arms and asked people for medicine to heal him. One man told her that she should go to Buddha to ask for medicine. She followed his advice and asked Buddha to cure her son. Buddha, full of compassion and sympathetic love, empathetically understood that the deep sorrow and agony of a mother who had just lost her only child would not allow her to accept the reality of death. Therefore, he did not tell her that the boy was dead and that no medicine was able to cure him. Neither did he try to comfort her by suggesting that she might have another son in the future. Instead, he said, “You have done well to come here for medicine, Krsā Gautamī. Go into the city and get a handful of mustard seeds.” And then the Perfect One added: “The mustard seeds must be taken from a house where no one has lost a child, husband, parent, or friend” (Mitchell, 1989, p. 108).

Krsā Gautamī was overjoyed when she heard this. She went from house to house to ask for the mustard seeds, and although everyone was willing to help, she was not able to find a family where death had not visited in the past. By evening, she was able to look at the reality of her situation objectively, and she understood the lecture that Buddha had given her. “How selfish am I in my grief!” she thought. “Death is universal; yet even in this valley of death there is a Path that leads to Deathlessness him who has surrendered all thought of self!” (Mitchell, 1989, p. 108).

Krsā Gautamī buried her son and returned to the Buddha to ask for guidance and support. The Buddha taught her about the impermanence of all things, the reality of suffering, and how to gain peace and liberation from the pain of grief and all suffering by developing equanimity and nonattachment and following the path that leads to enlightenment. According to the story, Krsā Gautamī became the first woman who attained enlightenment under the guidance of the Buddha (Mitchell, 1989).

The Foolishness of the Wise and the Wisdom of Fools

Because truth is not necessarily straightforward but can be approached from a variety of perspectives, the advice wise people give might sometimes sound foolish to others. Conversely, a wise statement does not indicate the depth of a person’s grasp of wisdom (Ardelt, 2004a; Sternberg, 2012). After all, sage advice can be given by fools. It is not simply what a person says but the intent with which a judgment is offered that distinguishes a wise individual from a fool. As Kekes (1983, p. 286) explains

A fool can learn to say all the things a wise man says, and to say them on the same occasions. The difference between them is that the wise man is prompted to say what he does, because he recognizes the significance of human limitations and possibilities, because he is guided in his actions by their significance, and because he is able to exercise good judgment in hard cases, while the fool is mouthing clichés.

Fools might speak wise words without a deeper understanding of their meaning, but perceptive listeners can discern the underlying truth. Conversely, if people are deaf to the wisdom of others, even the wisest words are rendered meaningless. In fact, wisdom per se cannot be taught directly or communicated, for example, through books or proverbs (Ardelt, 2004a; Blanchard-Fields & Norris, 1995; Schwartz & Sharpe, 2006). Since books, proverbs, and wise sayings only contain descriptive knowledge, readers must develop their own deeper interpretative knowledge for wisdom to emerge. Descriptive knowledge consists of a simple description of facts, whereas interpretative knowledge necessitates a deeper understanding of the descriptively known facts, which ultimately leads to a transformation of the individual (Kekes, 1983).

Because wisdom cannot be taught directly, wise teachers often “trick” their disciples into understanding and sometimes might deem it necessary to act like a fool to get a particular point across (e.g., Hanna & Ottens, 1995; Randall & Kenyon, 2001; Yamada, 1979). The difference between a sage and a fool is that wise individuals know what they are doing, whereas fools give sage advice accidentally without truly understanding or benefiting from the advice.

For example, the way Buddha taught depended on the mental state of his students. On one occasion, he simply held up a flower and smiled. This particular gesture might have looked foolish to others, but it brought complete realization of the truth to the one student for whom it was intended (Kohn, 1994). By contrast, the story of Buddha’s brother-in-law (or first cousin), Devadatta, who tried to take over Buddha’s role by imitating his words and gestures without having progressed on the path to wisdom himself, illustrates that fools will not enjoy long-lasting success (Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001). According to the Vinaya Pitaka, Devadatta was more interested in power, honor, and renown than in liberation from all suffering. His goal was to become the leader of the Sangha (i.e., the community of monks who followed Buddha’s teachings), and he devised several schemes to kill the Buddha with the help of Prince Ajātasattu, his benefactor. After all assassination attempts failed, Devadatta challenged Buddha to introduce stricter rules for the monks (to be forest dwellers only, to eat only begged-for almsfood, to wear refuse rags, to be tree-root dwellers, and not to eat any meat or fish), which Buddha refused to implement. Devadatta then used Buddha’s rebuke to create a schism in the Sangha. He went to the community of monks, convinced 500 newly anointed members to follow the stricter rules and departed with them. When Buddha heard about the departure of Devadatta with the 500 monks, he sent his chief disciples Sāriputta and Moggallāna after them.

Devadatta was sitting teaching the Dhamma [path to enlightenment] surrounded by a large assembly. He saw the venerable Sāriputta and the venerable Moggallāna coming in the distance. He told the bhikkhus [monks]: “See, bhikkhus, the Dhamma is well proclaimed by me. Even the monk Gotama’s chief disciples, Sāriputta and Moggallāna, come to me and come over to my teaching.”

…Now when Devadatta had instructed, urged, roused and encouraged the bhikkhus with talk on the Dhamma for much of the night, he said to the venerable Sāriputta: “Friend Sāriputta, the Sangha of bhikkhus is still free from fatigue and drowsiness. Perhaps a talk on the Dhamma may occur to you. My back is paining me, so I will rest it.”

“Even so, friend,” the venerable Sāriputta replied. Then Devadatta laid out his cloak of patches folded in four, and he lay down on his right side in the lion’s sleeping pose, one foot overlapping the other. But he was tired, and he dropped off to sleep for a while, forgetful and not fully aware. (Vinaya Pitaka Cullavagga, 7:4, as cited in Ñanamoli, 2001, pp. 268–269)

After Devadatta had fallen asleep, Sāriputta and Moggallāna taught the assembled monks Buddha’s true teachings and then led them back to the Buddha. When Devadatta awoke and found out what happened, he got so upset that he vomited blood. Although Devadatta initially gained many followers by imitating the Buddha, he was ultimately discredited, abandoned, and died in disgrace, because even many of his followers came to realize that he valued authority over authenticity (Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001).

Wisdom Is Timeless and Universal yet Relative and Changing

Wisdom is timeless and universal (Clayton, 1982; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Levenson & Crumpler, 1996), because it provides universal answers to universal questions that are concerned with the basic predicaments of human existence, such as the meaning and purpose of life, physical and mental suffering, loss, and ultimately death. Since those issues are universal, wise solutions related to those issues need to be universal as well (Assmann, 1994; Holliday & Chandler, 1986).

However, wisdom is also flexible and fluid, resembling a process of becoming more than a state of being (Blanchard-Fields & Norris, 1995; Clayton & Birren, 1980; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990). In fact, openness to experience has been one of the most consistent correlates (Ardelt, 2011a; Glück & Bluck, 2012; Le, 2011; Levenson, Jennings, Aldwin, & Shiraishi, 2005; Mickler & Staudinger, 2008; Staudinger, Maciel, Smith, & Baltes, 1998) and predictors of wisdom (Helson & Srivastava, 2002; Wink & Helson, 1997). Because one goal in the pursuit of wisdom is the comprehension of the true or deeper meaning of phenomena and events (Chandler & Holliday, 1990; Sternberg, 1990b), wisdom cannot be gained by simply hearing or reading about its timeless and universal truths, but rather must be realized to be understood (Ardelt, 2004b; Hall, 2010; Moody, 1986). According to Kekes (1983), the knowledge inherent in wisdom is not necessarily new knowledge but newly understood or interpretative knowledge. Interpretative knowledge illuminates the personal significance and meaning of generally known facts. For example, everyone knows that humans are mortal. However, to really understand the significance and meaning of the fact that I as well as all my loved ones will die someday requires interpretative knowledge or wisdom (see the example of Krsā Gautamī above). Wisdom has to be realized through a reflection on personal experiences, which will transform the individual in the process (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Ardelt, 2000b; Ferrari et al., 2012; Glück & Bluck, 2012; Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2005; Yang, 2008a). For example, after his mother died, a wise elder realized the universal truth that he was not grieving for the deceased but his own sense of loss, which ultimately helped him to overcome his grief (Ardelt, 2005, p. 14).

[I had t]he thought that: why am I fretting? You’re fretting for yourself. That’s selfishness. That is selfish of you. Because you’re really crying for yourself. You’re missing her. But Mother is at peace. She got tired. And I guess that’s the time when you do as much as you can do or want to do. You’re ready. You’re not going to hasten it or do anything to cause it, but you’re ready. And she had told us she was ready, so what are you crying for? And for a short time I worked on it badly, but I don’t cry anymore.

Although the essence of wisdom is timeless and universal, concrete expressions of wisdom are context specific and depend on the level and mode of understanding of the people involved (Jacobs, 1989; Schwartz & Sharpe, 2006). This paradox might explain why expressions of wisdom vary across cultures (Edmondson, 2012; Takahashi, 2000, 2012; Takahashi & Overton, 2005). For example, the manifestations of wisdom in developing countries or in Eastern societies can be somewhat different from its manifestations in Western cultures (Jeste & Vahia, 2008; Takahashi & Bordia, 2000; Yang, 2001). The techniques teachers use to convey their wisdom are influenced by the unique circumstances of the situation, such as the cultural customs, religious traditions and practices, and the mental states of the persons who impart and seek wisdom (Birren & Svensson, 2005). Yet, the deeper meaning and underlying truth of those expressions of wisdom are invariant to time and place (Jacobs, 1989; Levitt, 1999). The wiser individuals become, the more they will recognize that all wise men and women across different historical times and cultures teach the same universal truths. In fact, because wisdom is universal, it can function as a bridge between generations as well as between people from different social and ethnic backgrounds (Clayton, 1982), but the concrete expression of wisdom always depends on the situation and the people involved (Jacobs, 1989; Schwartz & Sharpe, 2006).

For example, the essence of Buddha’s teaching remains relevant and valid today, even though numerous social and political changes have taken place during the last 2,500 years. Millions subscribe to the four noble truths that (1) life is suffering, (2) the cause of suffering is craving and attachment, (3) removal of craving and attachment means the end of suffering, and (4) to end suffering, one needs to follow the noble eightfold path: right views, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration (e.g., Ñanamoli, 2001). Although Buddha’s teachings are conveyed to individuals in different terms and forms than 2,500 years ago, for example, through books, tapes, the internet, and films, rather than recited by a monk in Sutra form, the general path to ultimate wisdom and the end of all suffering remains the same. In fact, mindfulness or Vipassana meditation, which has become quite popular in recent years (e.g., Baer, 2003; Chiesa & Serretti, 2009; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Rosch, 2012), contains the essence of the original practice that the Buddha taught (Hart, 1987).

Affective Dimension: Love

Self-reflective thinking leads to deeper insights into one’s own and others’ motives and behavior and to a reduction in self-centeredness, subjectivity, and projections, which, in turn, are likely to increase a person’s sympathetic and compassionate love toward others (Ardelt, 2000b; Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2005; Levitt, 1999; Pascual-Leone, 1990). One important step in the development of wisdom and compassionate love is the acceptance of reality, including one’s own and other people’s faults and limitations. This does not mean, however, that a wise person will lead a life of indifferent acceptance and nonaction. On the contrary, such an individual is free to engage in actions that truly benefit others (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Kekes, 1995; Kupperman, 2005). A wise person does not unconsciously react to external and internal stimuli. By acknowledging and accepting external and internal forces, wise persons are able to weaken their power and ultimately change reality.

Self-Development Through Selflessness

Truly wise people, such as the Buddha, tend to be the most psychologically developed individuals. They are mature, psychologically healthy, autonomous, and fully liberated from all external and internal forces (Ardelt, 2000b; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Levenson & Crumpler, 1996; Mickler & Staudinger, 2008; Pascual-Leone, 1990). Through the development of equanimity and the complete mindful acceptance of the present moment, wise persons achieve inner peace (Ardelt, 2005; Hart, 1987). Yet, a wise person is also selfless—that is, free from any attachments to the self (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Curnow, 1999; Layard, 2007; Levenson et al., 2001; Takahashi, 2000). How can we explain the paradox that the highest level of self-development necessitates the dissolution of a sense of self?

Wise individuals’ selflessness is not equivalent to low self-esteem or a low sense of self-confidence (Helson & Srivastava, 2002). Maslow (1970, p. 200) even pointed out that “…the best way to transcend the ego is via having a strong identity.” There is a dialectical relationship between selflessness and self-knowledge (Levenson & Crumpler, 1996; Levitt, 1999). Only individuals who know who they are can overcome their self-centeredness. The quest for self-development and wisdom initiates a process of self-knowledge that reveals the illusory nature of the self (Ardelt, 2008b). People on the path to wisdom realize that the self is not a stable entity but a social construct (Mead, 1934; Metzinger, 2003) that consists of attachments and aversions to social identities, personality characteristics, behavioral tendencies, etc. (Levenson et al., 2001). Through the practice of mindful self-reflection and self-examination and the direct experience and acceptance of reality with its ever-changing nature, the attachments and aversions of the egotistical self gradually dissolve, which results in greater concern for the well-being of all and an altruistic, all-encompassing love (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Helson & Srivastava, 2002; Maslow, 1970; Rosch, 2012; Takahashi, 2000). For example, when describing wise exemplars, two students wrote (Ardelt, 2008a, p. 100)

[My wise] grandfather shows a lot of sympathy and compassion for people. He never holds grudges and always knows what is best for everyone. He never seems concerned about his own welfare, but more concerned about the welfare of the people around him.

Amongst the many lessons my [wise] great grandfather taught me, the most valuable was the one that I learned watching him live his daily life. In every situation, my great grandfather looked for the good in people. He always put himself on the line for others and truly knew the value of charity. He was extremely self-less and caring.

Hence, wise people’s self-development ultimately leads to selflessness or self-transcendence manifested in thoughts, feelings, and deeds toward the benefit of all rather than only their own self-interests (Kupperman, 2005; Levenson & Aldwin, 2012; Levitt, 1999; Rosch, 2012).

For example, the Anguttara Nikāya relates the story of a Brahmin who, after encountering the Buddha meditating under a tree, asked him whether he was a god, an angel, a spirit, or a human being. The Buddha answered that he was neither. By attaining enlightenment, he had overcome his egotism, transcended the self, and was able to live entirely for others, at peace and in harmony with the world (Armstrong, 2001).

Such a death to self was not a darkness, however frightening it might seem to an outsider; it made people fully aware of their own nature, so that they lived at the peak of their capacity. How should the brahmin categorize the Buddha? “Remember me,” the Buddha told him, “as one who has woken up.” (Anguttara Nikāya, 4:36, as cited in Armstrong, 2001, p. 161)

Buddha’s enlightenment experience resulted in a feeling of all-encompassing love for all beings. Out of compassion, Buddha started to teach the path to enlightenment to others to relieve them from their miseries, and he continued to do so for the rest of his life (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001). Even at the moment of his death at the age of 80 and without regard to his own discomfort, he taught the path to enlightenment to a young ascetic who eagerly asked about the realization of the ultimate truth and the cessation of all suffering (Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001; Thomas, 1949). Enlightenment, which is considered the highest form of spiritual self-development, resulted in selflessness.

Involvement Through Detachment

Wise people tend to observe reality with equanimity and detachment, as it really is and not as they would like it to be (Hart, 1987; Levenson et al., 2001; Maslow, 1970). Yet, they are not indifferent to the fates of others (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2005). On the contrary, because wise individuals have transcended their self-centeredness, subjectivity, and projections, they experience sympathetic and compassionate love toward others (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Kramer, 1990; Orwoll & Achenbaum, 1993). They are more concerned about collective and universal issues than about their own personal well-being (Clayton, 1982; Kupperman, 2005; Sternberg, 1998). Moreover, their public involvement in collective and universal issues is often more effective than that of others because they can see reality more clearly and objectively (Levenson et al.).

Wise people know not only what they should do to benefit themselves and others (Clayton, 1982) but also what they should not do, especially in critical or difficult life situations (Ardelt, 2008a; Kekes, 1983, 1995). They are less distracted and influenced by egotistical concerns and, therefore, can concentrate all their energy and effort on the realization of the common good (Yang, 2008b). Yet, while wise individuals feel sympathy and compassion for others, they are not overwhelmed by emotions but maintain a calm and balanced mind even in extreme situations (Ardelt, 2005, 2008a; Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1990; Hart, 1987). For example, a student reported (Ardelt, 2008a, p. 85)

[One] reason I consider my grandfather to be wise is his composure. He is always very even keeled and I have never honestly seen him get worked up about anything. Even at times of absolute joy all one sees is a very satisfied smile. I believe that this is an important mark of wisdom as he understands that there is always going to be good and bad events in one’s life and that fussing about it changes nothing. Furthermore, he is able to live by this in addition to understanding it. The balance he lives his life by is ultimately the reason I consider him to be wise.

Wise people manifest what Erikson (1964, p. 133) called a “detached concern with life.” They are involved, but at the same time, they also remain detached and do not, for instance, seek to control other people’s lives (Randall & Kenyon, 2001).

There are many stories of how Buddha and his disciples changed the attitudes and behavior of people who came in contact with Buddha’s teachings. One example is the story of the attempted assassination of the Buddha (Ñanamoli, 2001). According to the Vinaya Pitaka, Devadatta convinced Prince Ajātasattu to send a man to kill the Buddha. To eliminate all traces of their involvement, Devadatta ordered two other men to kill the man on his return, four men to kill the two men, eight men to kill the four, and sixteen men to kill the eight.

Then the one man took his sword and shield and fixed his bow and quiver, and he went to where the Blessed One was. But as he drew near, he grew frightened, till he stood still, his body quite rigid. The Blessed One saw him thus and said to him: “Come, friend, do not be afraid.” Then the man laid aside his sword and shield and put down his bow and quiver. He went up to the Blessed One and prostrated himself at his feet, saying: “Lord, I have transgressed, I have done wrong like a fool confused and blundering, since I came here with evil intent, with intent to do murder. Lord, may the Blessed One forgive my transgression as such for restraint in the future.”

“Surely, friend, you have transgressed, you have done wrong like a fool confused and blundering, since you came here with evil intent, with intent to do murder. But since you see your transgression as such and so act in accordance with the Dhamma, we forgive it; for it is growth in the Noble One’s Discipline when a man sees a transgression as such and so acts in accordance with the Dhamma and enters upon restraint for the future.” (Vinaya Pitaka Cullavagga 7:3, as cited in Ñanamoli, 2001, pp. 260–261)

The Buddha taught the man the path to enlightenment, and after he understood the wisdom of the path, he asked to be accepted as one of Buddha’s followers. The Buddha consented and told him to leave by a different path. When the two men waited in vain for the one man they had been instructed to kill, they followed up the path until they encountered the Buddha sitting under a tree.

They went up to him and after paying homage to him, they sat down at one side. The Blessed One gave them progressive instruction. Eventually, they said: “Magnificent, Lord! … Let the Blessed One receive us as his followers…”

Then the Blessed One dismissed them by another path. The same thing happened with the four, the eight and the sixteen men. (Vinaya Pitaka Cullavagga 7:3, cited in Ñanamoli, 2001, p. 261)

Loving-kindness, sympathy, and compassion were Buddha’s major tools for accomplishing change in others. His goal was not to force his teachings on the world, to accumulate a large number of followers, or to establish a powerful religious sect but to relieve the suffering of humankind. People who were ready to see the truth that he taught could easily follow his teachings, but Buddha was equally resigned to the fact that many chose not to pursue the path to wisdom and enlightenment (Armstrong, 2001; Carmody & Carmody, 1994).

Change Through Acceptance

Although one goal of wisdom is to perceive and accept reality as it is (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Hart, 1987; Maslow, 1970), paradoxically, the process of acquiring wisdom changes one’s self, one’s sense of reality, and ultimately reality itself. Individuals typically perceive themselves and the world through a veil of subjectivity and projections. When people manage to accept and objectively observe the reality of the present moment, however, the nature of phenomena and events change for them, including the phenomenon of the self, which initiates a process of self-transformation (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Assmann, 1994; Gadamer, 1960). Their self-centeredness and egotism decrease, and they develop more empathy, sympathy, and compassion for others. This, in turn, is likely to improve their general relationships with others (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991; Ardelt, 2000a, 2008a). Because wise individuals can see reality more clearly by having transcended their own subjectivity and projections, they are not offended and hurt, even if they become the target of other people’s negative projections and adverse behavior (Hart). Instead of reacting with negativity, such as anger, rejection, or depression, wise persons empathetically understand other people’s limited perspectives and, therefore, are likely to respond to their negative behavior with forgiveness and compassionate love (Ardelt, 2008b). In the process, wise individuals often are able to help others overcome their subjective projections and negative emotions, particularly in difficult life situations. Moreover, the compassionate love that emanates from wise persons tends to have a profound positive effect on people who come in contact with them (Ardelt, 2008a). As one student wrote (Ardelt, p. 100)

The Dalai Lama … in many ways is the epitome of wisdom. In listening to many of the Dalai Lama’s [talks] you immediately feel an overwhelming sense of humbleness and kindness emanating from his teachings. At the core of his beliefs is always radiating compassion and love to each [and] every life form you come in contact with.… Not surprisingly, you will find that the large majority of people immediately fall in love with the Dalai Lama upon either seeing him speak or simply exposing themselves to his valuable lessons in life.

In this manner, a wise individual gradually improves the world. For example, by observing and accepting the truth within himself without reacting with either craving or aversion, Siddhartha Gautama became the Buddha, the Enlightened One, a completely changed person (Carmody & Carmody, 1994; Kohn, 1994; Ñanamoli, 2001). Through his teachings on perceiving and accepting the reality of the present moment, he changed and still continues to change many people in search of wisdom and enlightenment (see the above examples of Krsā Gautamī and the reformed assassins). Hence, through acceptance and loving-kindness rather than a political or social revolution, Gautama Buddha changed the world.

Conclusion

This chapter explored the paradoxes of personal wisdom in its reflective, cognitive, and affective domains. In the reflective domain, building on the classical insight “I know that I do not know,” we explained why the development of wisdom requires a will-not-to-will and an act of nonaction, how loss can be gain, and how liberation can be attained through the acceptance of limitations. In the cognitive domain, we discussed how wise judgment is possible in the face of uncertainty, the difference between the wisdom of fools and the foolishness of the wise, and how wisdom is simultaneously timeless and universal yet relative and changing. Finally, in the affective domain, we described how self-development leads to selflessness, how wise people are involved while remaining detached, and how an acceptance of reality changes reality. People who follow the paradoxical path to wisdom will gain liberation from internal and external forces, get closer to the truth, and develop unconditional love.

Yet, how can we judge a person’s degree of wisdom if it consists of a collection of paradoxes? Without attempting to assess the paradoxes of wisdom directly, we have tried to measure the underlying reflective, cognitive, and affective dimensions of the paradoxes by developing a self-administered three-dimensional wisdom scale (3D-WS; Ardelt, 2003). The 12 items of the reflective wisdom dimension assess the ability and willingness to look at phenomena and events from different perspectives (e.g., I always try to look at all sides of a problem) and the absence of bitterness, subjectivity, and projections (e.g., things often go wrong for me by no fault of my own—reversed). The 14 items of the cognitive wisdom dimension capture in a reverse way a deep understanding of life and the desire to know the truth, by measuring the ability or willingness to understand a situation or phenomenon thoroughly (e.g., ignorance is bliss—reversed), knowledge of the positive and negative aspects of human nature (e.g., people are either good or bad—reversed), an acknowledgement of ambiguity and uncertainty in life (e.g., there is only one right way to do anything—reversed), and the ability to make important decisions despite life’s unpredictability and uncertainties (I am hesitant about making important decisions after thinking about them—reversed). The 13 items of the compassionate wisdom dimension gauge the presence of positive, caring, and nurturant emotions and behavior (e.g., sometimes I feel a real compassion for everyone), including the motivation to invest in other people’s well-being (e.g., if I see people in need, I try to help them one way or another), and the absence of indifferent or negative emotions and behavior toward others (e.g., I am annoyed by unhappy people who just feel sorry for themselves—reversed). Wisdom, assessed by the 3D-WS, has been found to be positively related to self-compassion, self-acceptance, humor, emotional regulation, mindfulness, savoring, mastery, autonomy, purpose in life, personal growth, optimism, curiosity/exploration, openness to experiences, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, pro-social values, forgiveness, positive relations, life satisfaction, general well-being, and happiness and negatively associated with neuroticism and depressive symptoms (Ardelt, 2003, 2011a; Bailey & Russell, 2008; Beaumont, 2011; Bergsma & Ardelt, 2012; Ferrari, Kahn, Benayon, & Nero, 2011; Le, 2011; Mansfield, McLean, & Lilgendahl, 2010; Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007).

Although most people profess to believe in the value of wisdom and wise judgments for themselves and their leaders (Assmann, 1994; Taranto, 1989), paradoxically, most modern societies do not make much effort to harvest and increase the wisdom of their citizens (Hall, 2010). As Clayton and Birren (1980, p. 131) stated, “Presently, our technological society encourages productivity rather than reflection and values problem-solving abilities rather than perceiving the assets of a broad questioning approach.” Growth in technical knowledge, economic affluence, and cognitive abilities appear to be more important in modern society than the nurturing of wisdom, but to solve societal problems in an interconnected complex world requires not only technical expertise but also wisdom (Etheredge, 2005; Maxwell, 2012). Layard (2005, p. 75) noted, “We face the paradox; in many ways life is better than fifty years ago. We have unprecedented wealth, better health and nicer jobs. Yet we are not happier.” According to Howard (2010), modern societies are characterized by paradexity, that is, the convergence of paradox and complexity, which individuals experience as (a) a depersonalization of social interactions while connecting to an ever increasing number of people through technical devices, such as e-mail, texting, and social network sites; (b) an overabundance of information without being able to separate useful information from “noise”; (c) an acceleration of technological innovations and “time saving” electronic devices that leave no time for reflection and solitude; and (d) an increasing sense of fragmentation and loss of a physically close community amidst growing universal interconnectedness. To deal with paradexity, Howard suggests that governments and businesses need to invest in the development of (a) wisdom to foster deep thinking and reflection, (b) mindfulness to pay closer attention to the present moment, (c) conversation skills to learn how to listen and conduct meaningful conversations with others that tackle the big rather than the trivial questions of life, and (d) a deep human interaction economy to meet others’ needs in an emotionally engaging and fulfilling way.

Yet, the pursuit of wisdom is too often considered to be a private task, whereas society actively sponsors the acquisition of intellectual capital through the education system. To succeed as a society in the area of paradexity, however, schools and universities should not only promote the acquisition of intellectual knowledge and technical know-how but also the development of wisdom (Brown, 2004; Ferrari & Potworowski, 2008; Maxwell, 2012; Reznitskaya & Sternberg, 2004). Although wisdom cannot be taught in the same way as intellectual knowledge and technical expertise, it can be taught indirectly by helping students to view and experience the world from many different angles so that they learn to make wise decisions and develop empathy and compassion for others (Bailey & Russell, 2008; Sternberg, 2001). We need wise politicians and business leaders who are concerned about collective and universal issues, consider the short-term as well as the long-ranging consequences of their actions to optimize the common good, and feel a strong sense of responsibility for present and future generations across the globe (Etheredge, 2005; Rowley, 2006; Solomon, Marshall, & Gardner, 2005; Sternberg, 2007; Yang, 2012). Such leaders engage in moral and ethical behavior that is directed toward the benefit of humankind rather than their own benefit and that of a selected group of people in power (Kekes, 1995; Kupperman, 2005; Sternberg, 2012). In spite of all those advantages, however, schools and universities rarely try to promote the acquisition of wisdom (Jax, 2005; Maxwell, 2012; Sternberg, 2001). Yet, an encouraging sign is the growing trend of introducing schoolchildren and college students to the practice of mindfulness meditation (Astin, 1997; Holland, 2006; Kabat-Zinn, 2000; Oman et al., 2007; Oman, Shapiro, Thoresen, Plante, & Flinders, 2008; Saltzman & Goldin, 2008; Wall, 2005), which was the main meditation technique that Buddha taught to his followers (Hart, 1987; Shapiro & Carlson, 2009). Students who learn to be mindfully present in the moment are likely to become more open to new experiences, better able to deal with daily stressors and adversity, more understanding, accepting, and compassionate toward themselves and others, and better future leaders (Hooker & Fodor, 2008).

We conclude this chapter with one last paradox: we need wisdom to understand wisdom. As Sternberg (1990a, p. 3) remarked,

To understand wisdom fully and correctly probably requires more wisdom than any of us have. Thus, we cannot quite comprehend the nature of wisdom because of our own lack of it. But if scientists were to demand total understanding, they would quickly be out of their jobs, because total understanding is something we can fancy we are approaching, but it is almost certainly not something we can ever achieve … the recognition that total understanding will always elude us is itself a sign of wisdom.

It is probably safe to assume that none of the researchers who have tried to comprehend and define wisdom (the authors included) is completely wise. Hence, all attempts to describe wisdom remain necessarily incomplete. However, by combining our diverse incomplete perspectives, we might arrive at a definition of wisdom that is more comprehensive than a single insight alone. In this regard, the scientific endeavor resembles the quest for wisdom: by looking at a phenomenon from different perspectives, we become aware of our own subjectivity and gain a more complete picture of the phenomenon in question.

References

Achenbaum, A. W., & Orwoll, L. (1991). Becoming wise: A psycho-gerontological interpretation of the Book of Job. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 32(1), 21–39.

Aldwin, C. M. (2007). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Aldwin, C. M., Levenson, M. R., & Kelly, L. (2009). Life span developmental perspectives on stress-related growth. In C. L. Park, S. C. Lechner, M. H. Antoni, & A. L. Stanton (Eds.), Medical illness and positive life change: Can crisis lead to personal transformation? (pp. 87–104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ardelt, M. (2000a). Antecedents and effects of wisdom in old age: A longitudinal perspective on aging well. Research on Aging, 22(4), 360–394.

Ardelt, M. (2000b). Intellectual versus wisdom-related knowledge: The case for a different kind of learning in the later years of life. Educational Gerontology: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 26(8), 771–789.

Ardelt, M. (2003). Empirical assessment of a three-dimensional wisdom scale. Research on Aging, 25(3), 275–324.

Ardelt, M. (2004a). Where can wisdom be found?—A reply to the commentaries by Baltes and Kunzmann, Sternberg, and Achenbaum. Human Development, 47(5), 304–307.