Abstract

Social value creation is important to not only social ventures, but also traditional and hybrid organizations seeking to increase their corporate social responsibility. Thus far, work on social value creation has focused on the customers or end users as the main beneficiaries of social value creation. Little work has addressed other beneficiaries or opportunities to generate social value and social wealth outside of that for direct recipients of products or services. This chapter extends work on value creation in strategic entrepreneurship to consider social value. Specifically, social value creation opportunities are identified across supply chain interactions both up and downstream from the organization. Implications for entrepreneurial and traditional ventures are discussed as well as possible research trajectories.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Social value creation provides a piece of the fundamental foundation that holds societies afloat, even during the darkest of times. Social value is the enrichment or sustained significant impact on society among one or more social welfare dimensions such as health, education, and environment (Dees 1998a; Peredo and McLean 2006; Zahra et al. 2009) . As welfare pertains to the basic needs of people, an increase in social welfare impacts some of the most fundamental of human conditions. Thus, without the creation of social value, a society’s most basic needs are not met (Young 2006) .

One of the most distinguishing factors for social ventures is the goal of social value creation (e.g. Dees 1998b; Austin et al. 2006; Cho 2006; Nicholls 2006) . Social ventures are a long-standing organizational form, defined as enterprises that attempt to meet society’s needs that existing government and economic structures cannot or will not suffice (Thompson et al. 2000) . Thus, social entrepreneurship improves social welfare by creating social value. In many instances, these social ventures provide goods and services that existing organizations do not recognized as appropriable, to a populace deemed unprofitable. As such, social ventures act outside of capitalistic and economic norms, challenging the conventions of a society based on these norms, while supporting the very foundation of that society. These same ventures attempt to meet society’s needs underserved by the existing institutions created and propagated by these same norms and conventions. This contention highlights the importance of social ventures to social welfare and the unique challenges faced by this organizational form.

A main stream of work on social value and social entrepreneurship has focused on identifying who is a social entrepreneur, in particular, individuals and institutions (Dacin et al. 2010; Thompson et al. 2000; Zahra et al. 2009) . The other stream of work has focused on measuring how much social value is created (Florin and Schmidt 2011; Ormistron and Seymour 2011; Young 2006) . This trend is reflected in practice as well. For example, both the Clinton Global Initiative and the Gates Foundation have launched programs to study the measurement of social value. Given the importance of who creates social value and how much is created, clarifying how organizations create social value is critical to further development of research in this area (Ormiston and Seymour 2011). Thus, this chapter builds theory by examining the mechanisms by which an organization can create social value.

The struggle to meet basic welfare needs unmet by existing governmental infrastructure and economic transactions highlights how social ventures operate in a world that may challenge their objectives and question their validity. As such, Mair and Marti (2006) suggest that understanding social ventures requires knowledge about the environment in which they operate. The exploration of how social value is created requires a consideration of a venture’s interactions with its environment. This chapter explores social value creation by considering a venture’s resource orchestration, particularly throughout its supply chain. Hitt et al. (2011) proposed an input-process-output model of strategic entrepreneurship concentrating on resource orchestration to create economic value. The authors argue that economic value can be created in each type of activity of a new venture: input, internal processes, and output. Building on this model, this study highlights the actions and interactions of a social venture across the supply chain that generate internal and external opportunities to create social value. The framework that emerges shows that social value creation is not isolated to an organization’s customers or direct beneficiaries, but can occur in a wide range of downstream, internal, and upstream activities as well. The framework is further examined using examples of social entrepreneurship around the world. Particular attention is given to recently created social organizations that have participated in the Global Social Benefit Incubator (GSBI) at Santa Clara University. Since 2003, the GSBI has helped over 120 social ventures develop sustainable business models through an intensive residential and online program. A third of the organizations operate in South East Asia (mainly India), a quarter in Africa and the Middle East, 15 % in South America, 5 % are located in Asia, and the remaining operating in the Middle East, United States, or multiple areas. The GSBI chooses organizations to participate based on the organization’s social-oriented mission, commitment to the social mission, potential benefit to society, and the likely scalability of the social venture. While their list is biased toward successful organizations, these data were chosen for that very reason; they provided detailed information about the business models that were effective for social venture survival. Over 90 % of the participating ventures were still alive in 2011. Data were collected for each venture regarding its operations and social value creation activities . The cases portrayed here are an illustrative sample of these data.

This chapter contributes to the body of research regarding social enterprise by extending the theoretical underpinnings of strategic entrepreneurship to social ventures. First, the chapter responds to the call for clarification of some of the fundamental concepts of the emerging field including social value and social wealth (Zahra et al. 2009) . Instead of focusing on economic outcomes or single-target group benefits (Haugh 2006) , this chapter considers economic and non-economic, direct and indirect benefits across multiple levels of impact. Next, this chapter suggests a theoretical grounding for the study of social ventures by extending the strategic entrepreneurship input-process-output model for value creation to social entrepreneurship. From this, a framework of social value creation opportunities emerges . The framework highlights the variety of activities and opportunities for social value creation, while providing insights into opportunity recognition literature primarily in the traditional entrepreneurship domain (Alvarez and Barney 2007) .

2 The Importance of Social Value and Social Wealth

The most prevalent goal of traditional ventures is to create economic value (Porter 1980; Sirmon et al. 2007; Hitt et al. 2011) . In contrast, social ventures are distinguished by having the objective of social value creation (Austin et al. 2006; Cho 2006; Zahra et al. 2009) . Social value is the improvement of social welfare, or meeting the needs of society that are underserved by government and economic organizations (Dees 1998a; Peredo and McLean 2006; Zahra et al. 2009) . However, social ventures ‘are sustainable only through the revenue and capital that they generate; thus, their financial concerns must be balanced equally with social ones’ (Dacin et al. 2010, p. 45, see also Webb et al. 2009) . Hence, to survive, a social venture must create value not only for the collective good, but also for the organization’s continued operations.

This balance need not be opposing; social and economic value can be both conflicting and complementary (Ormiston and Seymour 2011). For one, social value builds on economic value. Figure 4.1 depicts the traditional view of value creation on the left side. Traditionally, organizations are evaluated in terms of their economic transactions and value appropriation from customers. Social value creation is more than economic transactions and estimates of customers’ willingness to pay. The right side of the Fig. 4.1 illustrates the relationship between social value and economic value. Economic profit and buyers’ surplus remain the same. Social value can be thought of as the value of a product or service beyond its economic value. Social value includes not only the value to a customer; it is ‘irreducible to and greater than the sum total of individual welfare functions’ (Cho 2006, p. 37) . Defined as a sustained significant impact benefiting society’s welfare (Dees 1998a; Peredo and McLean 2006; Zahra et al. 2009) , social value transcends individual customer value to include multiple stakeholders across levels of analysis such as community, environment, industry, and supply chain. Social wealth is the collective value of the product or service when taken in aggregate. For example, providing affordable, clean drinking water benefits each individual customer and customer value can be determined by the amount paid for the product. At the same time, providing water to an impoverished customer creates social value by reducing the likelihood that she gets sick and infects other community members. If she has a family, the end users who consume the water and its products will also be less likely to become sick. In turn, the economic contributors (working members) to the family will suffer fewer days missed from work due to waterborne illnesses, thus increasing earning power. Social value also includes the contribution of value to indirect customers and stakeholders. As such, social value incorporates the value generated by the interactions of the focal organization with community members and the community-at-large. In the case of clean water, social value is created for the community by reducing the number of members getting sick, thus reducing the health care costs paid by the community.

It is important to note that be they non-profit, traditional, or governmental, the distinguishing factor for social ventures is their dedication to generating economic value beyond the boundaries of their own organization. While value chain analysis focuses on the economic value created by a firm through the sale of goods or services, social value is not reflected solely in value appropriation to the organization alone. We must go beyond the organization to understand the creation of social value. Similarly, social wealth is the collective gain to firms, customers, and society. As such, social wealth includes the value created for the organization, the value created for direct and indirect customers, and the value created for stakeholders and society. Therefore, social wealth includes benefits or contributions to the overall welfare of society, covering all levels of analysis from individual and firms to communities and the environment. Social wealth also captures the triple-bottom-line or social, economic, and environmental value. Taken together, the community has social wealth in the economic profit, buyer’s surplus, and social value created.

3 Creating Social Value and Wealth

While the creation of value in traditional ventures has been a popular topic of research, we know little about how an organization creates social value or the creation of social wealth as a whole. Thus far, social entrepreneurship work has focused on the consumers of a social venture as its primary beneficiaries, be they direct customers, end users, or community members (Haugh 2006) . This attention may be due to the field’s use of customer counts and economic outcomes as indicators of the beneficial impacts of an organization’s activities (Florin and Schmidt 2011) . Example of such metrics include the number of people that an organization provides access to clean water, the number of vaccine vials administered, and a count of meals served. However, these metrics capture only part of the picture as they tend to focus on direct downstream beneficiaries in single level analysis. Since organizations can create social value by improving the welfare of direct and indirect customers, stakeholders and society, it follows that the field must extend the analysis of social value creation to include opportunities with beyond the target beneficiaries. A recent effort led by standardization organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization and B-Labs is starting to provide organizations with tools to measure their social and environmental impact, including standards regarding community engagement. Other organizations such as Ceres, Global Reporting Initiative, GoodGuide, and Underwriters Laboratories have joined this effort. However, no set of metrics has been adopted and the organizations range greatly on what they consider pertinent. Thus, the analysis of social value creation remains unresolved.

An organization interacts and connects with society not only in the sale of its output, but also in its interactions with inputs and the internal processes. Thus, social value is not simply what the organization does for its end users. Additionally, while work on social ventures tends to focus on direct beneficiaries; positive (and negative—see Dacin et al. 2010) social externalities at large may outweigh individual gains. Similarly, in addition to downstream beneficiaries, social value is created when an organization attends to societal needs that exist upstream to their firms as well. For example, Coast Coconut Farms not only produces an eco-friendly line of skincare products, but also they use sustainable procurement practices to obtain raw materials. To better understand social value, we must consider other entities with which an organization interacts that provide opportunities to create social value. The following section discusses the creation of social value in multiple parts of the supply chain and levels of analysis.

If we traditionally evaluate an organization’s economic value creation in terms of their economic transactions, it follows that their social transactions will provide insight into their social value creation . We can do so adopting and extending an economic framework, such as the supply chain of an organization. All organizations take in resources to create economic value in the form of a product or service for customers. Hitt et al. (2011) developed an input-process-output model of value creation for strategic entrepreneurship from its supply chain interactions . This model was based on a more general model proposed by Ireland et al. (2003) that concentrated on defining the domain of strategic entrepreneurship. The input-process-output model articulated value creation for the firm, stockholders, and stakeholders such as society at large. Building on this model using the literature on social value and social wealth, I have extended the strategic entrepreneurship model to social entrepreneurship. Figure 4.2 illustrates the adapted input-process-output model for social entrepreneurship. This model depicts the three primary areas in the value creation process: the inputs or upstream resource providers, the process or internal operations, and the output or downstream customers and stakeholders. This arrangement goes beyond what is commonly referred to as a supply chain by providing a multi-level view of an organization’s ecosystem. On the left side of Fig. 4.2 are inputs that include materials and resources from suppliers, community, society and the organization itself. Next to each input is an illustration of social value creation. For example, an organization can create social value through its choices of raw materials (e.g. choosing sustainable materials over others types). Similarly, procurement practices such as transportation considerations provide additional opportunities. Supplier choice and sources of employees follow in this regard. An organization’s relationships and interactions with its community also provide opportunities to create social value through the commitment to support social welfare in the area. Organizations also use their own resources as inputs to create social value.

The internal processes of the focal organization are depicted in the middle of the Fig. 4.2. These can be thought of as resource orchestration, which is essential for gaining a competitive advantage (Sirmon et al. 2011) . Internal to an organization resources are orchestrated and inputs are transformed, thus creating economic value. How an organization operates influences the social welfare inside and outside of the firm. Examples that will be developed further in this chapter include employee training, community development, manufacturing, finance, and use of retained earnings.

Finally, outputs are depicted on the right and consist of products or services and benefits derived from their use. An organization creates products and services as well as externalities, or those indirect beneficiaries and unintended consequences, all of which can create social value. In addition to individual customer value, outputs can create value for organizations, communities, and society. Thus, organizations create social value by improving the welfare of those with whom it immediately interacts and indirect beneficiaries.

As described here, social value creation can occur throughout the input-process-output model. Table 4.1 illustrates examples of opportunities to create social value in the three areas of the model, as well as examples of organizations that work to create social value in these areas. While most social organizations do not create social value across all three primary areas—input, process, and output—Table 4.1 shows that some companies act on opportunities throughout the system. In particular, Cows to Kilowatts, Xayan IT, and Ideas at Work provide examples of organizations that create social value on multiple levels throughout the system. For example, Cows to Kilowatts is a Nigerian energy organization formed from the partnership between Dr. Joseph Adelegan, who holds a doctorate in civil and environmental engineering, and the Biogas Technology Research Centre in Bangkok. Together they worked to reduce the amount of pollution being created by the largest slaughterhouse in Nigeria, the Bodija Market Abattoir. To do so, the organization engaged its inputs, internal processes, and outputs to create social value on all fronts. Figure 4.3 illustrates the company’s efforts. The next section elaborates opportunities for social value creation in each area of the input-process-output model using the Cow to Kilowatts organization as a foundational case, supplemented with examples from other organizations.

3.1 Social Value Creation with Outputs

Since work measuring value creation traditionally focuses on outputs in products or services, it is appropriate to start the discussion of social value creation examples here . As discussed, outputs create social value when they are used to address social problems. Organizations using outputs to create social value often target downstream recipients of their products or services who are most vulnerable to the social problem at hand. Organizations can reach those suffering the social problem through three means: their product or service, their direct target customers, and indirect beneficiaries.

Products and services attend to social problems by attempting to directly alleviate the issue. For example, many areas of the world lack access to energy sources that do not pollute their air and water. Cows to Kilowatts addresses the overwhelming lack of clean energy sources in Nigeria by supplying poor communities with cleaner-burning cooking oil, biogas, and fertilizer. Other organizations such as Lifeline Energy provide technology to produce sustainable energy from solar and wind sources. Riverbank Filtration treats polluted water to provide safe clean water that not only improves the environment, but also reduces illness for those who drink it. Bushproof provides clean water and renewable energy products to rural communities in Africa. Thus, products and services in themselves are an essential source of social value.

Social value creation is perhaps easiest to identify when an organization directly targets customers suffering a recognized social problem. Poor communities have been recognized in Sub-Saharan Africa and India and alleviation of their poverty is the focus of Cows to Kilowatts, Lifeline Energy, and Riverbank Filtration, respectively. During emergencies, many Indians lack affordable transportation to health care facilities. Ambulance 1298 provides such transportation to improve the health of the poor throughout Mumbai. VisionSpring provides eyeglasses to the impoverished and disabled in India. Ikamva Youth provides education, training, and mentorship to disadvantaged high school aged youth in South Africa. Greenstar and Blue Energy are two other organizations that create value by providing marginalized customers a product—energy—to which they would not normally have access. Depending on the cost, price, and customer value, an amount of economic value is produced. However, the social value created may be invaluable to those being served.

Social value can be created beyond immediate customer value when the product or service indirectly influences the welfare of a community or society, particularly those collectively suffering from a social problem (see Fig. 4.1). Indirect beneficiaries of social value creation are neglected in the literature; however, direct and indirect benefits aggregate into social wealth, which is critical to understanding the health of a community or society. For example, the customers of Cows to Kilowatts, Greenstar and Blue Energy can use the energy provided as a means to do actions that they were not able to perform previously, or as means to make an activity easier. This ability can improve their way of life and level of health. But social value creation is not just the impact on customers or stakeholders; it includes the interaction between the social enterprise and society. Social value creation can occur in the effective development of an organization’s relationships. Cows to Kilowatts’ social mission entails reducing water and air pollution produced by slaughterhouses in a poor Nigerian community. The primary measure of social value creation is the number of people served by improved water supplies that were affected by pollution, not the amount of oil sold. While their direct customers benefit from the product, the community at large benefits from lower pollution, which may improve the health of current and future generations. In fact, indirect beneficiaries far outnumber the direct customers. In the cases of Ikamva Youth and Xayan IT, the training services that they provide directly increase the labor options of the recipients. The addition of skilled workers to a community shifts the labor market to jobs that require more education and training, which typically garner higher wages. A well trained community labor market that brings in higher wages can contribute to the economic development of the community. Social value here is created at the individual and societal levels. Consequently, the social value created by an organization may be underestimated if indirect beneficiaries are not considered.

3.2 Social Value Creation Inside the Organization

In addition to an organization’s outputs, internal opportunities abound for social value creation . Areas of internal resource orchestration that are particularly well suited for social value creation include employees, community development, manufacturing, financing, and use of retained earnings.

Employees can be the beneficiary of social value creation in many ways. In Cows to Kilowatts, employees are trained and provided opportunities for job advancement that they would not typically have access to due to the remote location or lack of education. Xayan IT hires employees from Bangladeshi universities and trains them further in technology areas to supply IT services to Xayan IT’s clients; thus creating employment for Bangladeshi youth while meeting the needs of its customers. Digital Divide Data hires and trains disadvantaged youth in Cambodia and Laos to provide IT services to clients around the world. Rwanda Rural Rehabilitation Initiative provides jobs to marginalized Rwandans in rural areas who would not have access to education through traditional means to work on community improvement projects. In these cases, social value is created through the internal training process. This is often not the direct product or mission of a social entrepreneur. Several socially attentive organizations (those that consider a wider range of social value creation opportunities) work with schools to create programs for underskilled or untrained community members that will ensure their employment in the organization after completion. Other opportunities to create value through employment include working with marginalized universities, training facilities, and communities. Organizations also create social value for employees by providing fair pay, safe working environments, or long term employment opportunities.

Community development is another area that is difficult to assess in terms of social value creation. However, this level of analysis is important since in some cases, the social value of outputs and training is contingent on the organizations interactions with the community. For example, supplying equipment to create safe drinking water for the poor has little value unless the organization develops a relationship with the community and educates members on the necessity of safe drinking water and how to produce it. Rural Africa Water Development Project, Riverbank Filtration, BushProof, and Naandi all worked with their local communities to establish sustained use of water cleaning equipment. If they did not do so, the projects would not survive and the organizations could not move to other communities to scale their solutions.

Honey Care Africa brings together community development and its internal resource orchestration to create social value. In its manufacturing process, Honey Care Africa centers its operations around the communities in which it operates. The organization uses each community’s unique structure and skills to organize the field operation of bee hive maintenance and honey collection. To succeed, Honey Care Africa emphasizes collective community engagement. As the community gains skills and increases its economic health, invaluable social wealth is built. Other organizations create social value in the manufacturing processes by minimizing environmental harm. CLEAN-India provides education to build community involvement to solve environmental issues in the area. Green Map System provides online tools to support collaborative mapmaking based on sustainable community development and environmentally friendly living practices. For each map, community members work together to supply and organize information about local environmental resources, organizations, educational institutions, issues, and services of interest. Ajb’atz Enlace Quiche supports community development in Guatemala through education about the Mayan culture. The range of social value creation through community development is vast .

Some organizations create social value through the financial aspect of their business such as pricing and the use of retained earnings. For example, Ambulance 1298 uses a unique pricing structure for their transportation services in Mumbai. The city has a large population of poor residents who cannot afford health care, let alone transportation to a health care facility. In an emergency, these residents go without. Ambulance 1298 offers transportation to hospitals using a tiered pricing scale. In general, the organization charges the customers taken to private hospitals, but not those taken to public hospitals who are less able to pay. Using this structure, they are able to supply emergency medical services to everyone in Mumbai. Instead of paying retained earnings out to shareholders, some organizations specify the reinvestment of those funds into other social value creation projects. For example, Ideas at Work invests 25 % of profits into improving the living conditions of local Cambodian orphanages. Other organizations use retained earnings to build schools, fund charities, or help other social value creation activities outside of the organizations’ reach. Hence, resource orchestration enables organizations to create social value beyond their target markets.

3.3 Social Value Creation with Inputs

Inputs are not generally considered opportunities for social value creation ; however, raw materials and the ways an organization obtains resources and materials produce interactions with social ramifications. Thus, raw material and their procurement, relationships with supplier organizations, community inputs, and organization-specific inputs are opportunities for creating social value. Raw materials represent an underestimated source of social problems and opportunities. For example, the number of substances polluting the environment is countless. This is especially apparent in communities near factories that are often plagued with polluting by-products from manufacturing. As mentioned, slaughterhouse waste is one such polluting by-product that is difficult and costly to dispose of and is filled with disease. Cows to Kilowatts addresses this social problem by using the slaughterhouse waste as its raw material. Traditional waste-treatment methods use a smelly, inefficient process that emits methane and carbon dioxide into the air. Once treated, this waste processed and rinsed into open drains, thus literally flowing into the water supply, polluting the water supply and making people sick. Cows to Kilowatts creates value by safely and effectively disposing of this waste that contributes to illness in the region and takes up landfill space.

Similarly, e-waste or disposed electrical and electronic equipment, consume a large amount of space in overflowing landfills, pollute land and water as they break down, and take a long time to degrade. Disposal companies in countries with lenient environmental regulations import e-waste. These countries tend to have a large impoverished population. The e-waste is discarded in poor communities, thereby polluting their land and water. Organizations such as All Green Electronics Recycling and Ash Recyclers use computers, cell phones, and televisions that have been thrown away as their main inputs. The organizations that use these waste materials reduce the burden to society by reducing garbage and helping the natural environment.

Other examples of social value creation through material inputs include using local, fair trade, organic and sustainably farmed raw materials. Industree Crafts focuses on using natural fibers that are sustainable in India. Coast Coconut Farms produces extra virgin coconut oil by using local wild organic coconuts through a fully sustainable and earth friendly process. Meds & Food for Kids emphases the use local raw materials in the production of their ready-to-use therapeutic food for Haitians.

Social entrepreneurs can also address social problems by considering the social value creation opportunities when choosing its suppliers. For example, organizations can create social value by obtaining materials or inputs made by non-traditional or local suppliers who may have few other opportunities. Community Friendly Movement acts as a manager for multiple artisan communities, connecting them with retailers and wholesalers who are looking for quality handmade products from India. Community Friendly Movement opens market channels and supply skills unavailable in rural villages. Similarly, eshopAfrica is a firm in Ghana that obtains products from underdeveloped artisan groups and community organizations. In doing so, eshopAfrica enables these artisans to earn a living. How an organization interacts with local communities can influence the creation of social value. For example, one critical input to any organization is its human resources. Organizations have many options in their search for employees and volunteers, but people are always needed. By employing jobless, disadvantaged, or untrained, the community benefits by developing active community members who are now able to contribute to the economic well-being of the area. Even traditional ventures have increased their social value creation by using more socially responsible procurement (Prahalad 2004) . Examples include reducing waste or emissions in transportation of materials, ensuring human rights within supplier firms, and requiring higher standards for inputs.

4 Discussion

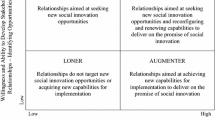

Organizations have many opportunities to create social value. The current literature tends define social ventures dichotomously: either the organization is or is not “social.” This characterization oversimplifies the possibilities for social value creation and limits our understanding of social entrepreneurship. All organizations interact with suppliers, resources, employees, and customers. I suggest that we look at the activities of organizations across their supply chain to better understand how they can create social value and at what level. Doing so helps refine theory about social entrepreneurship. By examining these interactions, we can we move from viewing social ventures as a homogenous, niche group to heterogeneous individual organizations (Florin and Schmidt 2011) . At the same time, instead of fragmenting the study of social ventures, refining our view of their characteristics facilitates the analysis of patterns and typologies. As the study of social entrepreneurship develops, researchers can use this framework to create more precise definitions and better measures of social entrepreneurship.

Measuring the performance of social ventures continues to be challenging due to the variation in definitions and confusion in the field (Short et al. 2009; Dacin et al. 2011) . Using the input-process-output framework of social value creation elaborated here facilitates the study of the differences in social venture performance by categorizing social value creation activities. Each of these categories can be measured and compared. Similarly, integrating these categories into a multi-item measure of social value may prove useful.

This chapter also draws attention to the importance of examining social value across levels of analysis, from individuals to societies. By focusing on direct beneficiaries as the measure of social value, work has largely overlooked that created for indirect beneficiaries. For example, externalities are ordinarily considered negative. However, we have discussed how the externality of reducing pollution creates social value. Thus, this chapter contributes to social entrepreneurship and social venturing scholarship by extending our understanding of social value creation to a wider range of activities and recipients.

The input-process-output framework of social value creation suggested here only offers an overarching perspective of social venture activities. Each type of opportunity for creating social value is a deep and curious area for future research. Within each opportunity, much work remains. For example, this chapter highlights the input-process-output model for social value creation ; however, each activity described deserves particular attention from raw materials procurement to influencing society at a macro level. Further analysis of the social value of networks and relationships will build on both social venture and network research. More study of resource orchestration will extend the resource based view of social entrepreneurship. Additional exploration of entrepreneurial opportunity discovery and creation through a social venture’s input, internal processes, and output will deepen our understanding of entrepreneurship on the whole.

This chapter highlights but only a few opportunities for social value creation, but the possibilities are limitless. Organizations can create social value in every action that it takes. However, not all opportunities are equal and not all environments are welcoming or accessible. In some cases, these options may undermine other social value creation in the organization (Austin et al. 2006) . In other cases, tackling too many opportunities is not sustainable. Although Cows to Kilowatts creates social value across many activities, some social entrepreneurs and ventures choose to focus their value-producing activity. It is imperative to recognize that acting on multiple opportunities does not classify an organization better or worse than more focused organizations. Similarly, actions that create social value in one setting may destroy it in another. Thus, options must be weighed carefully in light of each organization’s context and circumstances. In our attempt to quantify social value creation, we must be careful not to simplify the equation to a few variables, losing the full picture (Weerawardena and Mort 2006) . Just as there are many opportunities, each context holds a myriad of impediments equally challenging to measure.

As organizations develop and relationships change, the type and level of social value creation may change as well. For example, there may be a pattern of development for social entrepreneurs in which the locus of social value creation shifts from one type of activity to another. On the other hand, there may be a pattern in the depth of social value creation as a social venture matures. A line of research investigating changes in social value creation activities can enrich theory building.

This chapter has implications for entrepreneurs as well. Entrepreneurs aiming to start a social venture can use this framework to better understand areas that fulfill their social mission or identify socially beneficial opportunities. Existing, traditional firms can also use this framework to determine which activities they may be able change to become more social and thus enhance their triple bottom line.

In summary, this framework provides a broader way to look at social value creation than simply the organization-customer link. While many organizations are already doing these activities, perhaps more attention is needed to emphasize or recognize these activities. By doing so, we include a large spectrum of the society and have a broader reach. Now we must act on our own opportunities.

References

Alvarez, S. A., and J. B. Barney. 2007. Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (1–2): 11–26.

Austin, J., H. Stevenson, and J. Wei-Skillern. 2006. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (1): 1–22.

Cho, A. H. 2006. Politics, values and social entrepreneurship: A critical appraisal. In Social entrepreneurship, eds. J. Mair, J. Robinson, and K. Hockerts, 34–56. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dacin, P. A., M. T. Dacin, and M. Matear. 2010. Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives 24 (3): 37–57.

Dacin, M. T., P. A. Dacin, and P. Tracey. 2011. Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organization Science 22 (5): 1203–1213.

Dees, J.G. 1998a. Enterprising nonprofits: What do you do when traditional sources of funding fall short? Harvard Business Review Jan/Feb:55–67.

Dees, J. G. 1998b. The meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship”: Stanford University and Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership. Working Paper.

Florin, J., and E Schmidt. 2011. Creating shared value in the hybrid venture arena: A business model innovation perspective. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2 (2): 165–197.

Haugh, H. 2006. Social enterprise: Beyond economic outcomes and individual returns. In Social entrepreneurship, eds. J. Mair, J. Robinson, and K. Hockerts, 180–205. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hitt, M. A., R. D. Ireland, D. G. Sirmon, and C. A. Trahms. 2011. Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating value for individuals, organizations, and society. Academy of Management Perspectives 25 (1): 57–75.

Ireland, R. D., M. A. Hitt, and D. G. Sirmon. 2003. A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. Journal of Management 29 (6): 963–989.

Mair, J., and I. Marti. 2006. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business 41 (1): 36–44.

Nicholls, A. 2006. Introduction. In Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable change, ed. A. Nicholls, 99–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ormistron, J., and R. Seymour. 2011. Understanding value creation in social entrepreneurship: The importance of aligning mission, strategy and impact measurement. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2 (2): 125–150.

Peredo, A. M., and M. McLean. 2006. Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business 41 (1): 56–65.

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press.

Prahalad, C. K. 2004. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: eradicating poverty through profits. Philadelphia: Wharton School Publishing.

Short, J. C., T. W. Moss, and G. T. Lumpkin. (2009). Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3 (2): 161–194.

Sirmon, D. G., M. A. Hitt, and R. D. Ireland. 2007. Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Academy of Management Review 32 (1): 273–292.

Sirmon, D. G., M. A. Hitt, R. D. Ireland, and B. A. Gilbert. 2011. Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. Journal of Management 37 (5): 1390–1412.

Thompson, J. A., G. Alvy, and A. Lees. 2000. Social entrepreneurship—A new look at the people and the potential. Management Decision 38 (5): 328–338.

Webb, J. W., G. M. Kistruck, R. D. Ireland, and D. J. Ketchen. 2009. The entrepreneurship process in base of the pyramid markets: The case of multinational enterprise/nongovernment organization alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (3): 555–581.

Weerawardena, J., and G. S. Mort. 2006. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. Journal of World Business 41 (1): 21–35.

Young, R. 2006. Social value and the future of social entrepreneurship. In Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change (pages), ed. A. Nicholls. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zahra, S. A., E. Gedajlovic, D. O. Neubaum, and J. M. Shulman. 2009. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing 24 (5): 519–532.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Woolley, J. (2014). Opportunities for Social Value Creation Across Supply Chain Interactions. In: Pate, L., Wankel, C. (eds) Emerging Research Directions in Social Entrepreneurship. Advances in Business Ethics Research, vol 5. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7896-2_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7896-2_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-7895-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-7896-2

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)