Abstract

Purpose

The work explores the development of inclusive businesses, paying particular attention to the mission and the motivations underlying the choices of sustainable businesses that—by increasing access to goods and services and creating new sources of income—benefit low-income communities and bring added value for companies and people living in poverty alike.

Research design/methodology

Our approach is both deductive and inductive. After having outlined the theoretical framework, we provide multiple case studies relative to different inclusive business experiences. This is followed by a discussion on the different approaches in which we try to categorize them according to two fundamental types: CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)-oriented approaches and CSV (Corporate Shared Value)-oriented approaches.

Findings

We found that there are a variety of inclusive business models whose differences can be predominantly attributed to the ethical perspectives at the base of their entrepreneurial formula.

Value/originality

The value of the study is attributable to the attention paid to the authenticity of the mission of inclusive business, which lies in an ethical orientation toward poverty and disadvantaged peoples. This helps evaluate inclusive business experiences, often less known—as the EoC (Economy of Communion) companies, or the “ideal motive” SMEs—in which the principles of inclusion, responsibility, and sustainability are based more on the authentic virtues and charisma of the entrepreneurs and managers than on the desire to conjure new ways of making a profit by reducing situations of poverty in different areas of the world.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)

- CSV (Corporate Shared Value)

- Inclusive business

- Authenticity

- EoC (Economy of Communion) companies

- CBE (Community-based Enterprises)

- “Ideal motive” SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises)

- Social enterprises

1 Introduction

One of the greatest challenges in business orientation toward CSR (corporate social responsibility) and CSV (corporate shared value) is the issue of poverty, often discussed in the context of the base or Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP). Over the next few decades, the incidence of poverty is likely to rise if the problem is not tackled aggressively (United Nations 2001; World Bank 2001). Today, the overwhelming majority of people who have to get by on less than $ 2 per day live in rural areas. By 2050, the planet will have 3 billion more people than it does today. The people at the bottom of the global income pyramid are not dispersed equally throughout the globe; they mainly live in the urban slums and villages of developing countries. Poverty is a multifaceted phenomenon (Narayan-Parker 2000) , and a holistic perspective is necessary to overcome it. In the last few decades, responsibility toward people, the planet, and profit (the so-called triple P; Elkington 1997) has been neatly defined (WCED 1987; World Economic Forum 2009; IBLF 2008) .

In September 2000, world leaders decided to adopt the United Nations Millennium Declaration, committing their nations to a new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty and establishing a number of objectives to be reached by 2015. This agreement, known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), refers to the development of a “global partnership for development” in which there is a specific role for companies (Nelson and Prescott 2008) . Most companies have the potential to make a contribution to the MDGs through one or more of the following three areas: core business operations and value chain; social investment and philanthropy; public advocacy, policy dialogue, and institution strengthening. An increasing number of large and globalized companies—known for their hard-nosed approach to business and for their narrow conception of capitalism—as well as small and medium-sized businesses (Jenkins 2007; Jenkins et al. 2007; Revell and Blackburn 2007) and social enterprises (Mair and Marti 2006) have embarked on important shared value initiatives (Hart 2010; Hart and London 2011) . The emergence of core business approaches to enhancing development impact comes along with an array of terminology for business that is responsible, sustainable, inclusive, pro-poor, high-impact, win-win, or triple bottom line (Table 11.1). “Inclusive business” is the term already used by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and Netherlands SNV. The inclusive business models also frequently appear in connection with the following two concepts: social enterprise/social business and corporate social responsibility. These models try to answer the question: “Is it possible to fight poverty through business?”

Social enterprise refers to both newly created and existing entrepreneurial organizations with a social dimension that pursue social objectives as part of their business model, among them fighting poverty. Social enterprises apply business logic to at least cover their costs (Borzaga and Defourny 2001; Dart 2004; Light 2006; Noja and Clarence 2007; EC 2012) . Social entrepreneurship is therefore defined as a process that aims to: alleviate significant problems and social needs (Light 2006; Mair and Marti 2006); generate social change (Mair and Marti 2006); alleviate the suffering of a specific group of people (Martin and Osberg 2007) ; generate a benefit to society with specific emphasis on poor and marginalized people (Schwab Foundation 2011); and create and distribute new social values (Peredo and McLean 2006) . The definitions agree then to consider social entrepreneurship as a means to alleviate social problems and to increase the well-being of two broad categories of beneficiaries: the community in general and specific groups of people who live in a situation of social disadvantage (the poor, the disabled, etc.).

Corporate social responsibility refers to the responsibility of companies (both large- and small-sized) to make a contribution to society and prevent damage. CSR is broadly defined as the extent to which firms integrate on a voluntary basis social and environmental concerns into their ongoing operations and interactions with stakeholders (Godoz-Diez et al. 2011) . Nevertheless, there is no single, commonly accepted definition of the concept of CSR (Carrol 1979, 1999; Gatewood and Carrol 1991; Hill et al. 2007) and many different ideas, concepts, and practical techniques have been developed under the umbrella of CSR research “including corporate social performance, corporate social responsiveness, corporate citizenship, corporate governance, corporate accountability, sustainability, triple bottom line and corporate social entrepreneurship”. “All these are different nuances of the CSR concept that have been developed in the last 50 years—and beyond” (Freeman et al. 2010, p. 235) . Most CSR definitions emphasize CSR’s orientation toward the social context beyond the technical, economic, and legal activities of business (Carrol 2008) . “Corporate Social Responsibility is the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the community and society at large” (Holme and Watts 2000, p. 8) . Following the European Commission, CSR can be defined as a concept whereby “companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their daily business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” (EC 2001, Green Paper, p. 6) and, more recently, as “companies’ responsibility for their impact on society” (CE 2011). CSR is placed at the base of the renewed European strategy for the period 2011–2014, which is oriented toward a “smart growth” (based on innovation and knowledge), a “sustainable growth” (based on a more efficient use of resources and so-called green energy) and an “inclusive growth” (based on the employment development and on the social and territorial cohesion).

Many companies strive to integrate CSR activities into their core business. Inclusive business pursued by companies also falls into this category. In fact, these types of initiatives also often originate in the CSR department in larger companies or are driven by entrepreneur behavior and attitudes.

Inclusive business refers to profitable core business activities that also tangibly expand opportunities for the poor and disadvantaged in developing countries. “Inclusive business models engage people living at the base of the economic pyramid (BOP) in corporate value chains as consumers, producers, and entrepreneurs” (Gradl and Jenkins 2011, p. 5) . By focusing on business viability “these new models have the capacity to be increased in scale, thus including thousands of people living in poverty. The emphasis is on ‘core business’ rather than on philanthropy” (Gradl and Knobloch 2010, p. 5).

In many countries, the poor are still excluded from economic and social development. The idea behind inclusive business can be synthesized in doing business with the poor to combat poverty. Both companies and people living in poverty can benefit from inclusive business, since it brings added value by integrating the poor into the value chain as consumers or producers, thus making a positive contribution to the development of companies, the local population and the environment (WBCSD 2004, 2007, 2008; Anderson and Billou 2007; Mair and Seelos 2007; UNDP 2008, 2010; Frandano 2009; Gradl and Knobloch 2010; Gradl et al. 2010; IFC 2010; Jenkins et al. 2010) . Private-sector institutions and especially governments play an important role in inclusive business ventures. They are responsible for protecting the interests of both consumers and producers and can also improve the overall conditions for business at the macro level. There are four main areas where a principle of inclusive business can be incorporated: supply chain, employment, products/services, and distribution channels. Inclusive business models can consist of: (a) developing or adapting existing supply and/or distribution chains in order to increase the participation of disadvantaged producers, informal traders, and employees; and (b) developing or adapting existing products and services needed by the poor and/or enabling greater access to these products and services to the poor while creating low carbon-emitting, climate-resilient businesses that help communities adapt to changing environments.

Evidence shows that inclusive business can truly make a significant contribution to fighting poverty. Virtually any business (not just that which is labeled “inclusive” and not just big corporations) can help a country develop, through taxes, employment, market expansion, and technology transfer. But are all inclusive businesses always authentic “good companies”? Are there different “ways of being” an inclusive business? What are the differences among approaches to inclusive businesses? Are their mission and governance aimed more at fighting poverty or at developing markets and increasing competitiveness? What distinguishes inclusive businesses from other types of companies (intended both for and non-profit companies)? Is it possible to discriminate different models of inclusive businesses depending on their mission and governance’s ethical orientation?

These basic research questions characterize the present work that reflects on, and tries to evaluate, the phenomenon of inclusive business that has recently been developed. The aim of the paper is to understand if the ethics underlying the approach (that can be read in the context of CSR ethical theories—Garriga and Melé 2004) distinguishes diverse models or typologies of inclusive business practices .

In order to reach this objective, our approach is both deductive and inductive. After having outlined the theoretical framework, we provide multiple case studies relative to different inclusive business experiences. This is followed by a discussion on the different approaches and an attempt to categorize them according to two fundamental types: CSR-oriented approaches and CSV-oriented approaches.

From a methodological point of view, the analysis of possible forms of inclusive business is based on three different approaches and on the use of diverse sources and techniques of data collection. The study of inclusive businesses was based on an analysis of the Endeva Report and information research through the Internet (by visiting the websites of several companies). For the EoC (Economy of Communion) businesses, we relied on the analysis of results of the empirical research. For SMEs (territorial companies), we summarized the results of previous empirical researches based on several companies and carried out through interviews, semi-structured questionnaires, participation to initiatives, and common meetings with the entrepreneurs. Finally, the analysis of community-based business and social enterprises was based on the literature review and on the analysis of examples described on the Endeva Report.

This paper is structured as follows: Sect. 11.2 presents the theoretical framework containing the phenomenon of inclusive business in relation to the concepts of CSR and CSV . In subsequent sections, several models of inclusive businesses will be presented, including an outline of the distinguishing features; examples and distinctions are drawn between those promoted by social enterprises, big companies, community-based business, small firms, and EoC companies . The concluding chapter contains reflections that have emerged with regard to the various typologies of company.

2 CSV, CSR, and Pro-Poor Partnership

Poverty leads to miserable living conditions for the poor and to limited economic and environmental sustainability as a consequence of a lack of resources and education and the use of inappropriate material in dealing with urgent and daily needs. From industrial countries and multinational organizations, specific international agencies have been heavily involved in interventions in the developing world over the last decades.

Traditional approaches to development suggest that it is the responsibility of the State and the public authorities to operate as institutional entrepreneurs in order to improve the existing institutional pressures faced by the inhabitants of disadvantaged communities (Evans 1995; North 1990). However, several contributions suggest that the State might not be the most appropriate level of action. Works in organizational theory (Tracey et al. 2011; Peredo 2003; Peredo and Chrisman 2006) and entrepreneurship (Mair and Marti 2009) suggest another approach, one that focuses on the activities of institutional entrepreneurs at a more micro-level. Such institutional entrepreneurs include public private initiatives (McDermott 2007; McDermott et al. 2009) and NGOs (Mair and Marti 2009), and at a lower level these factors may also engage in activities that aim to change the institutional arrangements .

On one end, the BoP perspective states that organizations can eradicate poverty by investing in BoP markets (Prahalad 2004) . For companies entering BoP markets, it is important to cultivate partnerships with the local community in the BoP market at stake by helping organizations access resources, customers, and employees (Monitor Institute 2009). Companies could team up with trustworthy local government players and NGOs. Elaborating on Carroll’s model (1979, 1999) , Gössling and Vocht (2007) studied and defined the organizations’ conceptions of their social role. They distinguished between narrow role conceptions (solely focus on economic and legal responsibilities) and broader role conceptions (also focusing on ethical and philanthropic responsibilities). They found that most companies present themselves as good corporate citizens.

In BoP ventures, the notion of selling to the poor has been replaced by business approaches that suggest sustainable value creation, implicating the development of strategies that serve triple bottom line goals (Hammond 2011). These include economic, social, and environmental benefits or, in other words, the responsibility to (and goals of) the “Triple P” of people, the planet, and profit (Elkington 1994) , which in the last decade has been neatly defined (WCED 1987; World Economic Forum 2009; IBLF 2008).

Several studies in the BoP literature framework reveals that three high level factors may need to be aligned in order to ensure optimized value creation of BoP venture (BoP strategy, partnerships, and product/service development) and that there is a delicate balance among the three (all three are interdependent and mutually influence each other).

Dobers and Halme (2009) point out that different capacities of organizations and their managers are implied to understand and address pressing CSR issues in different cultural contexts (i.e., South America and Africa), including corporate actions not only based on economic investments but also on programs in areas such as enhancing capacity in detecting tax fraud, antitrust, and the unveiling of corruption cases; even if legislation is a task of politicians, governments, and international governmental bodies, these matters should also be seen as a CSR issue (Garriga and Melé 2004) . They stress the urgency for concerted efforts by the private sector, public sector, and non-governmental organizations to develop structures and institutions that contribute to social justice, environmental protection and poverty eradication.

Over the last 5 years, the rise of CSR and the growing recognition that business and development objectives often coincide has placed the private sector at the heart of the struggle to raise living standards in emerging economies. Recently, businesses (as represented by the International Chamber of Commerce) have had extensive involvement in the many UN and other international meetings and conferences (Reed and Reed 2008; Dossal 2004; Richter 2004; Del Baldo 2012; EC 2002, 2004) that have identified the crucial components of a global partnership for development and its interlinked priorities. These conferences reflect a global consensus on the challenges facing humanity and set out a roadmap for cooperative action by governments, business, and other groups in society. Poverty eradication has emerged as the foremost unifying priority to face. Yet despite all of their hard work and creativity, many people are still trapped in poverty. They lack not only income and capital but also, and more importantly, real opportunities for growth and development. This lack of opportunity is to a great extent due to a lack of markets.

In this regard, business has consistently emphasized the importance of mobilizing domestic resources and encouraging local entrepreneurship, foreign direct investment, private capital flows, and overseas development assistance and integrating the informal economy into the formal economy. Creating an environment conducive to enterprises of all sizes and in all sectors to create jobs and pursue technological innovation and cooperation—coupled with sound governance and policies to reduce barriers to international trade and foreign direct investment—is the best model for helping people to get out of poverty and paves the way to reaching the MDGs.

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) represent the most comprehensive and universally agreed-upon development goals, embodying the international community’s pledge to create a better and healthier future for billions of people in developing countries by 2103. The goals strive to reduce poverty and hunger, empower women, increase access to education, health care, clean water and sanitation, protect the environment, forge global partnership for development, and reduce the incidence of a number of deadly diseases.

Tackling the challenges of achieving the MDGs will require concerted effort and partnership by all actors in society. The UN, other intergovernmental organizations, and national governments are encouraged to seek out the involvement of the private sector in these vital efforts and include business representatives in discussions on how to take them to the next level. Over the last decade, considerable progress has been made but significant challenges remain.

Success will depend on the willingness and capacity of local and national governments to create and implement the appropriate policy frameworks and to pursue partnerships with business and other stakeholder groups. In turn, these efforts will need to be supported by the international community. Sound public policies and investments are central for achieving the MDGs and accelerating economic growth, but they are not enough. The private sector is the engine of innovation and growth providing incomes for rural and urban populations. Where possible, countries should draw on the private sector to complement governments in designing, delivering and financing interventions to achieve the MDGs. The economic growth and wealth creation that is essential for the achievement of the MDGs will come primarily from private enterprise (Nelson and Prescott 2008) .

Reaching the MDGs calls for collaboration among all stakeholders, starting from enhancing the role of the private sector (which can serve as a catalyst for action) and development (creating jobs, building skills, developing technologies).

Most in business view the millennium development process as integral to their business interests and to their global citizenship. Business will continue to engage respectfully and openly with communities, governments, and other stakeholders around the world in pursuit of the millennium development objectives.

Companies and entrepreneurs can make a significant contribution to human development. They can (and must) improve the quality of life in developing countries and drive toward more sustainable paths of development in terms of consumption and production. Large globalized companies especially have the processes necessary to create products that meet the needs of producers and consumers living in poverty as well as the management know-how to grow successful models and expand their reach. On the other hand, developing countries and people living in poverty will play an increasingly significant role in future business development for different reasons. First, the markets at the top to the income pyramids are largely saturated, thus lower-income segments open opportunities for the positioning at an early stage of these markets and secure competitive advantages. Second, developing countries offer an alternative supply source of raw materials for the manufacturing and food industry (which are becoming ever more scarce and expensive). The supply chain can be strengthened by teaming up with the producers of natural raw materials and handcrafted products as well as local service providers: not only because the supplier base is broadened, but also because it leads to product diversification, better quality and unique selling propositions such as fair production conditions or traditional ethnic handicrafts. Third, they offer a stable environment for investment and trade: many governments are working on reforms aimed at facilitating trade processes and improving reliability for businesses. Finally, business models that improve the opportunities for people living in poverty are meeting with more support.

Political leaders and governments are, in turn, publicly supporting company activities that contribute to the MDGs. We can mention, for example, the UNDP’s Growing Inclusive Markets Initiative, the Clinton Global Initiative, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD)-SNV (Netherlands Development Organization (SNV) Alliance, and the MDG Call to Action (UK).

Among organizations that are aimed at supporting the development of inclusive business we can consider, for example, the Business Innovation Facility (UK Department for International Development—DFID by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP in alliance with International Business Leaders Forum). Among the projects aimed at promoting inclusive businesses we also can mention the develoPPP.de program, created by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) (www.develoPPP.de).

On the other hand, Porter and Kramer (2011) state that, departing from a new conceptualization of capitalism, new models are emerging that aim at the application of the principle of “shared value,” which involves the creation of economic value in a way that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges. “Shared value then is not about personal values. Nor is it about ‘sharing’ the value already created by firms—a redistribution approach. Instead, it is about expanding the total pool of economic and social value” (Porter and Kramer, p. 65) .

In light of this principle, businesses try to reconnect company success with social progress. Thus, shared value is not social responsibility but a new way to achieve economic success, and the corporation’s purpose must be redefined as creating shared value that focuses on the connection between societal and economic progress. In other words, successful businesses and successful communities can go hand in hand. NGOs and governments recently have appreciated this connection. The concept of shared value can be defined as policies and operating practices that enhance the company’s competitiveness while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions of communities in which it operates, expanding the link between societal and economic progress (competitive advantages and social issues). There are numerous ways in which addressing societal concerns can yield productivity benefits to a firm (i.e., regarding energy and water use, employees’ safety and skills, environmental impact, procurement, and enabling local cluster development). Mostly, companies can create shared value opportunities in three key ways: reinventing products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain, and enabling local cluster development (Porter 1998).

Greater opportunities seem to arise from serving disadvantaged communities and developing countries. “The societal benefits of providing appropriate products to lower-income and disadvantaged consumers can be profound, while the profit for companies can be substantial” (Porter and Kramer 2011, p. 68) . As capitalism begins to work in poorer communities, new opportunities for economic development and societal progress increase exponentially. This requires the identification of all the societal needs, benefits that are or could be embodied in the firm’s products or in the supply chain and distribution methods.

Porter states that CSV differs from CSR programs (Porter and Kramer 2006). These programs focus on reputation and have a limited connection to the business, while CSV is internal to a company’s profitability and competitive position and involves new and heightened forms of collaboration. It will benefit from insights, skills and resources that cut across profit/nonprofit and private/public boundaries.

“The fact is, the prevailing approaches to CSR are so disconnected from strategy as to obscure many great opportunities for companies to benefit society” (Porter and Kramer 2011, p. 68) . If corporations analyze their opportunities for social responsibility using the same frameworks that guide their core business choices, they discover (as Whole Foods Market, Toyota, and Volvo have done) that CSR can be much more than a cost, a constraint, or a charitable deed—it can be a potent source of innovation and competitive advantage (Porter and Kramer 2011). They propose a fundamentally new way to look at the relationship between business and society that does not treat corporate growth and social welfare as a zero-sum game. They introduce a framework that individual companies can use: to identify the social consequences of their actions; to discover opportunities that benefit society and themselves by strengthening the competitive context in which they operate; to determine which CSR initiatives they should address; and to find the most effective ways of doing so. They also stress the role of social enterprises/entrepreneurs that “are not locked into narrow traditional business thinking and are often well ahead of established corporations in discovering these opportunities” (Porter and Kramer 2011, p. 70) .

Following these preliminary remarks, attention will be focused in subsequent chapters on the various forms that the phenomenon of inclusive business can take on and will include a critical analysis and classification of these forms .

3 Different Models of Inclusive Businesses

As previously stated, inclusive business refers to profitable core business activity that also benefits low-income communities and tangibly expands opportunities for the poor and disadvantaged, especially in developing countries, thus making a positive contribution to the development of companies, the local population, and the environment. When people living in poverty are included in business either as producers or consumers, opportunities can emerge on both sides: Inclusive business thus helps fight poverty on the one hand and increases competitiveness on the other .

Added value and benefits lie in several areas for people in poverty that come from participating in inclusive business:

Basic needs: Many basic needs are still not met today, but examples of inclusive business models already exist that provide food, access to clean water, electricity and Internet, wastewater disposal, medical supplies, housing construction, and education.

Productivity: Access to electricity, telephone, and Internet as well as financial services, such as loans and insurance, make day-to-day life more efficient and open up new business opportunities for individuals and microenterprises.

Income: Farmers, artisans, and other producers find new sales channels; services are in demand and jobs are created. Lower-priced products increase real income.

Empowerment and confidence: New possibilities for consumption and income and new forms of market participation or creation give people the feeling that they have more control over their lives.

At the same time, companies can boost their competitiveness in a variety of ways:

New markets: Establishing growth-intensive sales and supply markets expands the supplier and customer base. These markets are expected to grow rapidly because of strong population growth and increasing income in many developing countries.

Enhanced Reputation: The contribution that inclusive business makes to society as a whole improves the image of the company and the trust placed in it by customers, suppliers, governments, investors, and the general public. This underscores the company’s CSR activities.

Employee retention and training: An employer’s commitment to pursuing social goals is important and strengthens the employees’ identification with the company. Having employees work in an inclusive business environment can also be beneficial for job and management training purposes and for the employees’ own personal development.

Innovations and the capacity for innovation: Creative solutions for products, processes, and business models are always the engine for company growth and a prerequisite for long-term market survival. As a result, a company’s overall capacity for innovation is enhanced by pursuing projects that follow an unusual logic, ask new questions, and new organizational solutions.

Environmental protection is also of particular importance for people living in poverty. Innovative technologies and solutions can make sustainable business possible in every respect—and create opportunities for the long-term growth of companies that have the necessary expertise.

During the G20 Summit in Cannes, France in November 2011, participants launched a global competition, “The G20 Challenge on Inclusive Business Innovation,” seeking to recognize businesses with innovative, scalable, replicable, and commercially viable ways of reaching low-income people in developing countries. Between November 2011 and February 2012, 167 applications were received from businesses in 72 countries.

The most innovative models are the result of creativity and business discipline that enabled the integration of the base of the pyramid in their value chains. The four main features of innovation are: building the capacity of the base of the pyramid, financing the base of the pyramid, adapting products for the base of the pyramid, and distributing goods and services to the base of the pyramid (IFC 2012, p. 3). These new business entrants—inclusive businesses—can increase competition, lower prices, and improve consumer choice, often bringing products and services previously unavailable or unaffordable (IFC 2012, p. 14).

Only a few success stories have been reported for inclusive business in a handful of industries, meaning much experimentation is necessary before arriving at a working model for each company. Nevertheless, a first guide of inclusive business experiences, provided by the Endeva Report (2010), explains how companies can take better advantage of inclusive business and tackle the specific challenges they face with the aim to inspire many new business ideas .

Local traditions and skills. Skilled workers in developing countries provide valuable services. Opportunities exist particularly in the case of labor-intensive and handcrafted products, such as those in demand for interior design. IKEA works with cooperatives and family-run companies in Vietnam to produce textiles and ceramics. The company concludes long-term contracts with the suppliers that have fixed payment terms, a mutually beneficial model. In this case, the inclusive business model is “Contract Production/Contract Farming,” a system that directly sources from large numbers of small-scale farmers or producers in (often rural) supply chains. The contractor organizes the supply chain, provides critical inputs, specifications, training, and credit to its suppliers, and the supplier provides assured quantities of specialty produce at fair and guaranteed prices. The wealth and diversity of natural raw materials makes it possible to safeguard, broaden, and improve the supply chain, make use of new and unusual materials and satisfy the quality criteria for “organic” or “fair.” Direct procurement setups bypass middlemen and reach into the base of the economic pyramid, enabling purchases from large networks of low-income producers and farmers in rural markets and often providing training for quality and other specifications. There are numerous examples in Africa (GADCO, Frigoken, AAA Growers, Masara N’Arziki, SOCAS, etc.) and India (Calypso Foods, KBRL, Mahagrapes, Agrocel, etc.) (Kubzansky et al. 2011, p. 10, 29) . The object of this model (which has also been developed in Brazil and Pakistan) is to promote measurable improvements in the key environmental and social impacts of cultivations worldwide to make them more economically, environmentally, and socially sustainable. In the case of cotton cultivation, 68,000 farmers grew “better cotton” during the 2010–2011 seasons in India, Pakistan, and Mali. The Better Cotton Initiative involves large companies and organizations like Tesco, IKEA, Adidas, Gap and H&M.

Services from tourism to translation. The service sector is very underdeveloped, but this is starting to change, thanks to the widespread availability of data networks. Digital Dividend in Cambodia and TxtEagle in Rwanda are start-up companies that rely on mobile technology to provide services like translation in local languages—a kind of micro-business process outsourcing. Interest is also growing in tourism that is committed to making a positive impact on the local culture and the natural environment, and in the process creating unique experiences for tourists. The company Hospitality Kyrgyzstan is an ecotourism operator in Kyrgyzstan that offers homestays with local nomad families. The local population is essential as a service provider here (Jenkins 2007; Berdegué et al. 2008) . This inclusive business experience can be regarded as an example of a mobile-enabled service. Mobile-enabled business models aim to leverage low-income ownership or use of mobile devices to provide information, transactions or services to low-income customers in a range of sectors including agriculture, healthcare service, livelihoods or other information services. Different inclusive business examples are present in Africa (Google Suite, KenCall, National Farmers’ Information Service, and Grameen’s Community Knowledge Worker Initiative) and India (Neurosynaptic, Thomson Reuters) (see Kubzansky et al. 2011, p. 10) .

The Case of Kenya Vodafone Group Communication for a development (Africa). In 1980, there were only four landline connections for every 100 inhabitants in Africa. Vodafone identified this opportunity and invested in the mobile network infrastructure on the African continent. Nowadays, one in four people in Africa has a cell phone. Both the phone companies and the users have benefited enormously. Entrepreneurs and farmers can conduct their business more productively, having access to information about prices and demand, allowing them to sell their goods at better terms and saving them unnecessary trips to markets. Skilled workers can be contacted directly by customers from different regions. In the private sphere, having a phone saves time and improves the quality of life (better access to information, and health care and emergency numbers that help protect against crime).

Together with its partner Safaricom, Vodafone offers additional services in Kenya. M-PESA, the mobile banking service, makes monetary transactions possible for people who don’t have bank accounts. This saves them time and money. The M-PESA’s service of mobile money solution was introduced in Kenya in 2006 and has rapidly grown. Vodafone’s success was immediate: In March 2010, M-PESA had 9.5 million customers and 10,000 new users sign up every day.

In 2010, 9.5 million Kenyans were already using their cell phones to pay for their groceries in supermarkets or to transfer money to their families. M-PESA service is fast, easy, and inexpensive, and no account is required. Both the phone companies and the users have benefited enormously (Endeva Report 2010, p. 15).

In general terms, these examples of inclusive businesses are related to large globalized companies (i.e., IKEA and Vodafone), which are active involved on poverty alleviation, but it is difficult to understand if this orientation is authentic or due to a “conditional morality” as we discuss in the following paragraph.

3.1 The MNC’s Role in Fighting Poverty

Large firms are acknowledging that combating poverty is not only important for contributing to a stable operating environment and managing risk but can also represent a major opportunity. Firms are implementing new business practices, often in partnership with public and civil society bodies, in order to develop these opportunities.

The UN Commission specifically looked into how the MDG potential could be realized, underlining the importance of multinational corporations (MNCs), although its main focus was on local businesses (UNDP 2004). The potential and opportunities of multinational companies (MNCs) in relation to poverty alleviation are receiving considerable attention (Kolk and van Tulder 2006) .

Their contribution is also recognized in the growing number of partnerships, in which expertise and knowledge, usually through best practices, are transferred. Such cooperation takes place in different forms, with governmental, non-governmental, and/or private participants. While criticism of the negative impact of MNCs continues to be heard (Hertz 2001; Klein 2002; Stiglitz 2002) , most policy attention tends to be drawn to their potential added value in alleviating poverty.

Furthermore, MNC poverty policies can address themselves to several areas: local conditions, dynamic comparative advantage, training, and monitoring. In the first case, MNCs carry out activities in harmony with development priorities, social aims, and the overarching structure of the host county; in essence, MNCs strictly obey national laws and regulations. In the second area, MNCs adopt and develop technology suitable to the needs of host countries, invest in relatively high-productivity, high-tech, knowledge-based activities, establish backward linkages with domestic companies where possible, and conclude contracts with national companies. In the third area, MNCs provide training for employees at all levels, which develops useful skills and promotes career opportunities; they participate in training programs organized by/together with governments and make services of skilled personnel available to assist in training programs. Finally, MNCs foster and strengthen local capacities to monitor the company’s poverty reduction programs (participatory methods), encourage the development of local poverty reduction indicators and targets to evaluate the company’s activities, and design poverty monitoring systems, which provide evaluations of the company’s anti-poverty programs.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development published a field guide resulting from its “Sustainable Livelihoods Project” (WBCSD 2004; WBCSD 2007). Almost 20 cases underline the fact that “doing business with the poor” could help MNCs to reach a largely untapped market of 4 billion potential customers. This is not just philanthropy but a CSR strategy that also makes economic sense and can give companies active in this way a competitive edge (Prahalad and Hart 2002; Prahalad and Hammond 2002) . MNCs can realize this by focusing on activities related to their core competencies and unique resources and capabilities utilizing local capabilities and knowledge about markets, production and external expertise through partnerships. MNCs might then “do well” in both an economic and societal sense at the same time, thus addressing criticism that companies need to concentrate on profit maximization and not be distracted from that objective (Henderson 2001; Whetten et al. 2002) .

The role of MNCs related to poverty at the international and macro level has been widely considered in the academic and societal debate. In the international policy discussion on the impact of MNCs in relation to poverty, different aspects have been mentioned: one side pays most attention to the negative effects of their activities and powerful positions, while the other stresses the poverty-alleviation potential. Developing countries still try to attract MNCs for a number of reasons, including their potential to help alleviate poverty. A focus on CSR offers the opportunity to emphasize the potential role of MNCs in regard to poverty alleviation.

CSR is generally seen as encompassing the legal, ethical, social, and environmental responsibilities of companies in addition to the traditional economic one (Carrol 1999, 2000) . Nevertheless, how MNCs act with regard to CSR depends on both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (i.e., sectoral interdependencies, as international companies operating in global industries).

Basu (2001) argued that MNCs can play four different roles regarding CSR and poverty. An MNC can choose not to be actively involved in alleviating poverty, while other are (a free-rider situation); it is active in poverty alleviation but only if other MNCs do the same (Basu’s concept of conditional morality); no MNC is involved in poverty alleviation (comparable to a “prisoner’s dilemma”); an MNC is the only company active on poverty alleviation. A framework of analysis can be derived using the OECD (2001) document in order to identify the main aspects related to MNCs and poverty: equality of opportunity and treatment; conditions of work; and collective bargaining.

In general terms, Kolk and Tulder (2006) state that MNCs are overall not (yet) very outspoken on poverty alleviation and that in general only few issues are addressed. They also state that sustainable solutions can only be reached by offering poor people “tools” (know-how, technology, and resources) to escape the poverty trap by themselves and that MNCs do not yet reach their full potential in offering these tools to the poor. Only if they themselves are actively involved will they be able to develop their full potential role as poverty alleviation.

They also point out the implications of conditional morality for action and policies that try to involve MNCs in poverty alleviation, and they stress the need for approaches that overcome the logic of “single (even if high profile) approach” adopted by MNCs, NGOs, and international organizations, since it is necessary to create an enabling environment that facilitates dialogue and actions at the sector level through a “community morality.”

3.2 The Role of Small-sized Businesses

Given that SMEs are such a vast sector of the economy at a local level, social entrepreneurs and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) continue to make a major contribution to the MDGs. Most of the world’s private sector activity takes place at this level, rather than within and between large firms, and although many of the brief examples in this report feature corporations, the world’s small-scale operators provide a huge additional range of replicable business approaches. Contact between large firms and the SMEs' sector takes place through company supply chains. As such, enterprise development and business linkage initiatives and other projects to transfer skills, technology and finance to small companies and social enterprises is one of the most important contributions that large national companies and multinational corporations can make to the MDGs. In Italy, whose socio-economic fabric is made up of small companies, entrepreneurs and their families, there are many zones whose values in terms of know-how, sense of belonging to a local community and to the same culture inspire entrepreneurial behavior. A recent piece of research, which centered on various cases involving Italian SMEs, allowed verifying an important connection between orientation toward sustainability of companies led by entrepreneurs (“champions of CSR”) and the sharing of those values typical of their local context (Harvey et al. 1991; Putnam et al. 1993) .

These values spring from the rural culture and from the culture of the Italian cities in Renaissance Humanism, which is the heritage of the civil economy of the historical tradition of the country. In contexts such as these, there are numerous companies, normally small-to-medium sized that—thanks to the entrepreneurial vocation and to the “civil charisma” of those subjects able of leading companies that present themselves as value-based organizations—offer tangible examples of innovative routes of sustainable development (Del Baldo 2010). First and foremost, the companies work within the context of their local territory albeit not exclusively, since they push themselves to support sustainability projects and actions on national and international levels. These routes are based on the capability of these entrepreneurs/companies to take part in and to activate networks that include several factors: banks, trade associations, unions, local authorities, non-profit organizations, chambers of commerce, and others.

Such entrepreneurs are capable of activating virtuous circuits. Charismatic people, who, thanks to their vision, are able to open new frontiers on human need and rights communicate with urgency their vision of social life; institutions subsequently extend these innovations into social structures. They are authentic champions of CSR capable of influencing and molding the socio-economic terrain from which they come (Jenkins 2004, 2006). And this comes from the richness and the appeal of their own virtuous testimony, able to “imitate the virtues.” The SMEs—especially “rooted” in their respective region and characterized by long-term, established mechanisms and rules—possess a good starting position for a sustainability strategy as a result of their structure and regional infusion (Storper 2005) . The strong ethical and moral base that molds the company’s mode of conduct is irrespective of the individual and has its roots in local traditions, which foster a model of sustainable entrepreneurship. A genuine commitment inspires these values-driven businesses to demonstrate their social responsibility and relational sustainability (Perrini 2006) . This dynamic occurs through the creation of networks through which companies interact with the local and extra-local context, rich in both tangible and intangible resources and through which social goods such as prestige, reputation, and friendship are exchanged (Del Baldo 2010; Del Baldo and Demartini 2012) . This relational logic flows into the construction of forms of local collaborative governance (Zadek 2004, 2006) centred on partnerships multi-stakeholders and on projects that sustain the co-evolution and territorial development following the logic/objective of the shared value. They also sustain a cultural change that considers rootedness and the relationship with the local community as a strong point for the creation of shared value (Porter and Kramer 2011) .

These companies can be considered forms of businesses as their tendency to social responsibility falls within the strategic profile and is desired by the entrepreneur. They are not always internationalized and therefore do not fight poverty through their local presence but maintain it from afar through networks of relationships with international associations. They fight poverty close to its context. In other words, they are themselves community-based businesses. In many cases, they have avoided impoverishing the areas in which they have set up and developed, by offering work, training, and environmental requalification to areas that would otherwise remain degraded or depopulated. They make up a fundamental component of the socio-economic community which they have contributed to building.

3.3 The Role of Community-based Businesses

There is increasing interest in the importance of communities, and researchers insist on the importance of paying more attention to the local level, to the institutional pressures that shape the context in which new ventures are created, moving beyond a view of entrepreneurs as disconnected from the local context in which they operate. This constraining aspect is especially critical and problematic in disadvantaged communities (Leca and Naccache 2011; UN-Habitat 2008) that live in informal settlements and slums where an important role can be played by institutional entrepreneurs (i.e., the activities of the Technological Incubator of Popular Cooperatives at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) who provide venture members with autonomy and eventually rely on them to diffuse institutional change within the communities.

Different authors have stressed the imperative of acting at the local level by stating that value creation and innovation through local business development are essential means for the alleviation of poverty and preservation of the natural environment (Peredo 2003) .

Drawing on theoretical considerations from different fields (entrepreneurship, environmental management, anthropology, and development studies) and focusing their attention on the regional Canadian and South Australian models of sustainable practice where organizations developed community partnerships, Peredo and Chrisman (2006) state that Community-Based Enterprise (CBE) come provides a potential strategy for sustainable local development.

CBE is defined as a community acting corporately as both entrepreneur and enterprise in pursuit of the common good. It is the result of a process in which the community acts entrepreneurially, to create and operate a new enterprise embedded in its existing social structure. “Furthermore, CBEs are managed and governed to pursue the economic and social goals of a community in a manner that is meant to yield sustainable individual and group benefits over the short- and long-term” (Peredo and Chrisman 2006, p. 4) .

They consider CBE as a promising strategy for fostering sustainable local development, since CBEs are created by community members acting corporately, and are the result of a process grounded in collective experience: They are based on available community skills; they are characterized by a multiplicity of goals depending on (and recognizing) the diverse needs of the members of their founding communities; and they are dependent on community participation. In summary, CBEs are built upon the collective skills and resources of the community, and they have multiple social and economic goals acting corporately in pursuit of the common good. CBE represents both the entrepreneurial process of venture creation and the venture created through the process. They are a product of incremental learning and are dependent on social capital since they are created on the basis of collectively owned cultural, social, and ethnic endowments (Bourdieu 1997; Putnam 1973) . In this context, being embedded is a concept that owes a good deal to the notion of the “gift economy.”

Most efforts to assist in the improvement of developing regional economies have in fact been unsuccessful because they have either been unmindful of local cultures and values or have been simply charitable programs that failed to address the root causes of poverty (Burkey 1993; Davis 1993; Cornwall 1998; Dana 1988; Sachs 1992) .

This means that overcoming poverty requires an understanding of the specific socio-economic environment in which that development is to take place (Peterson 1988) . Several authors (Light and Rosenstein 1995; Morris 2000) stress the need to look at the interaction among communities, families, and individual entrepreneurs (Cornwall 1998; Onyx and Bullen 2000) . This also means thinking of the community orientation of a society in terms of “embeddedness,” “social capital,” and “social networks local communities,” which create collective business ventures, and, through them or their results, aim to contribute to both local economic and social development.

There are different documented cases of community-based enterprise: the Mondragon Corporation Cooperative in Spain (Greenwood 1991; Morrison 1991); the village of Ralegan Siddhi in India (Hazare 1997) ; Retirement Living in Elliot Lake, Canada (OECD 1995); the Walkerswood Community in Jamaica (Lean 1995) ; Floriculture Using Hotsprings Energy in Amagase, Japan (OECD 1995); New Dawn Enterprises in Atlantic Canada (MacLeod 1986); and the self-managed community enterprise of Llocllapampa and the Community of Chaquicocha Trade Fair, both in Peru (Peredo 2003) . Community-based solutions have been emerging for environmental conservation and income generation among poor populations in Latin America (Peredo 2001; Tenenbaum 1996), Asia (Hazare 1997; Lyons 2002), Africa (Nelson 2000), and poor rural areas of rich countries (Lyons 2002; MacLeod 1986) .

Community-based enterprises represent both a promising solution to the problems faced by many small communities in poor countries, and—in a macro-economic sense—an alternative and promising model for development that sits in an unconventional form of entrepreneurship. This is based on regarding collective and individual interests as complementary and interconnected and seeing communal values and the notion of the common good as essential elements in venture creation.

An exemplary case of community-based business is found in the Tiviski camel milk dairy of Mauritania:

Tiviski is a camel milk dairy in Mauritania (the Sahel region of Africa), where the majority of the population still depends on agriculture and livestock for their livelihood. The extreme conditions that Tiviski has been confronted with since its formation in 1989 are a good example of the structural challenges posed by inclusive business projects .

Tiviski has successfully set up Africa’s very first camel dairy in Mauritania. Today, the company sells 20 products. Tiviski produces a wide range of dairy products ranging from fresh milk to its “Camelbert” cheese sold in many small stores in the country. More than 1,000 families supply camel milk. Success was driven by many investments and innovations: Tiviski, for example, set up a refrigeration and collection system. A separate cooperative organization supports the herders, makes credit available offers veterinary services, and provides advice about livestock breeding and herding. The producers are paid with vouchers that can be submitted to Tiviski for payment. The success of the dairy also led Mauritanians to look at animal husbandry “as an economic activity, not merely as a way of life passed on from father to son” (Case Study 6, Endeva Report 2010, p. 27; Gaye 2007) .

3.4 The Role of EoC Companies

The companies belonging to the economy of communion project (EoC companies) are an example of businesses in which entrepreneurship and managerialism are characterized by the tendency to communion, universal brotherhood, and the common good (Argiolas et al. 2010; Gold 2010; Baldarelli 2011; Bruni and Zamagni 1995; Zamagni 1995) .

On May 29, 2011, the EoC project finished 20 years of life. From the beginning, one of the most important elements of the project was the need to reply better to poverty, especially in Africa. These companies are the results of the charismatic founder, Chiara Lubich, who is also the founder of the Catholic movement of the Economy of Communion (Lubich 2002, 2003) .

The pioneers of this project were pushed forward into taking part in it, since they were enlivened by a dream: that of alleviating poverty near and far to achieve universal fraternity, which is developed through the adoption of adopting a culture of “giving.”

“During the Brazil trip which was in May 1991, Chiara Lubich was left profoundly touched by the strong social inequality encountered … in the favelas that surround the metropolis of São Paulo. (It is) in this context that she launches a proposal: to have companies be set up, guided by competent people in such a way as to make them operate in an effective way so as to gain assets…” (Gold 2010, pp. 333–334) .

The experience of the EoC companies has developed over 20 years and we can see from the following tables their evolution (www.edc-online.org). Tables 11.2a, b refer to May 29, 2011 on the occasion of the 20-year anniversary of the project launch.

Around the mid-1990s, the International Office of Economics and Labor, a supporting organ of the EoC made up of scholars, entrepreneurs, and students, was constituted. During the course of its meetings, contingent and strategic EoC problems were examined, and an attempt was made to solve them in such an adequate manner. In fact, several EoC commissions (Gold 2010) operate on various levels: international, national, and local, functioning as “laboratories” to understand strategies in order to offer efficient solutions to problems that projects might face.

In 1999, a “Manifesto for an Economy of Communion” was drawn up and, in 2008, new guidelines were designed to lead EoC companies to make their management and organization characteristics more evident based on the following main points: (1) entrepreneurs, workers and enterprises; (2) the relationship with the customers, the suppliers, the civil society, and the external subjects; (3) ethics; (4) quality of life and production; (5) harmony in the workplace; (6) training and education; and (7) communication (www.edc-online.org).

These principles have been promoted, at the same time, by way of the creation of “Schools for Entrepreneurs” and other training initiatives, which, since 2001, have been aimed at orienting managers to the most important values of the project, teaching entrepreneurs and managers the optimum use of company governance tools and enhancing the exchange of experiences within logic of reciprocal growth .

From these points, we may infer some managerial models, amongst which that one which considers the pillars of dialogue, trust, and reciprocity (Argiolas et al. 2010) .

Industrial poles have been built in order to make the entrepreneurial experience of EoC companies more visible. They first came into being in Brazil and later they spread to various parts of the world: Italy-Loppiano (FI), Argentina, Belgium, Portugal, and the USA. Furthermore, EoC entrepreneurs prefer the small and medium dimensions because they are leaner, more flexible, and make the creation and development of relational assets smoother (Gui and Sugden 2005) . More than 900 businesses follow the Economy of Communion model. Most are small and medium size, but some have more than 100 employees. They function in various sectors of production and service, and are located on every continent. The 45 businesses in the United States include an import-export business, a law office, an environmental consulting firm, a tutoring business, a violin shop, an accounting firm, an apparel labeling shop, a goat farm, several restaurants, and a chocolate factory.

The phenomenon of the EoC company has been studied by scholars in various fields (Gold 2010; Bruni and Uelmen 2006) , including empirical and statistical levels (Baldarelli 2011) . Initially, they were only economists (Bruni 2002). Later on, scholars from almost every discipline joined them (Baldarelli 2006; Argiolas 2006; Gold 2010) .

In relation to the consistency of the phenomenon, the data obtained from the Centre for Italian EoCs shows that there are approximately 230 businesses throughout all various parts of the country. Among these, a recent study involving 43 companies (micro-companies (73 %); small companies (18.60 %); and medium companies (9 %)) has revealed the coherence of their governance according to the project guidelines and the specificity of the EoC companies, with particular relevance to the following aspects: the enhancement of human labor; the importance of ties and relationships; time dedicated to listening and dialogue; involvement based on trust; attention to the competitive logic of the market in order to find the right balance between efficiency and communion; and concern to satisfy clients based on the ability “to put oneself in others’ shoes.”

Being an EoC company does not mean applying a corporate philosophy but represents a balance between practice and theory using known corporate models.

This represents the economic turning point in a lifestyle, which has a profound impact on all aspects of behavior. The fundamental content of lifestyle is “the culture of giving,” and those who share its various aspects are committed to spreading such a culture. The culture of giving transforms the modality through which production and the distribution of wealth take place. The novelty of this proposal lies in its consideration of the local community and its specific nature a central and significant variable.

The mission of EoC companies reverberates within a whole list of objectives in the absolute conviction of wanting to actively take part in the betterment of collective well-being and especially to spring to the aid of the most proximate situations concerning material and spiritual poverty.

The presence of both social enterprises and profit-making companies, among the EoC companies project, leads some authors to define them as “companies with an ideal motive” (Molteni 2009) , in that they are the fruit of an ethical substratum, which directs every field of human behavior and, therefore, that economic behavior too .

The significance of this ethical substratum shines through the account of Teresa and Francis Ganzon of Bangko Kabayan in the Philippines :

Toward mid-1997, at the onset of the Asian crisis, the Philippines had to come to terms with a devaluation of 60%, which hit the financial sector the most. Default on loans and errors in industry were connected with the liquidation, and therefore some banks began to have difficulties due to the loss of clientele … In the following months, yet more close-downs around us added to the panic … We realised that we were part of a greater family, that which included all the other entrepreneurs who live the experience of the Economy of Communion. We shared this experience with them … The moral encouragement we received, especially via Internet messages, helped us a lot in continuing the journey … moreover, we had discovered force in trust and safety which each person in the organisation had … our manager who represents the minority of the partners, put aside 2.6 mln dollars’ credit line for the bank without asking for any guarantee in exchange.

Two aspects qualify the EoC’s model of corporate governance: The first is inserting ethical principles into the production of profit; the second is the wealth of the company thought of, not as an end in itself, but as a means that allows achieving a much wider aim which is, as stated earlier, universal fraternity.

The EoC profits can be divided in three equal parts and used for direct aid for the poor, educational projects that can help further a culture of communion, and development of the businesses. A full two-thirds of its profits are destined to broader community development, either as direct aid for the poor, or to support educational programs that further a culture of giving—both aspects which may not necessarily have a tight connection with employees, customers, or others with a more direct interest in the business itself. A fundamental role is played by the poor themselves for whom such businesses are established in the first place. Indeed, adhering to the Economy of Communion project, the entrepreneur decides to devolve a third of his positive income to resolve situations of indigence (whether nearby or far-away) (Bruni and Uelmen 2006) .

The active presence of persons (the poor) who depend for their survival and development on that third of the assets of the companies of the project, sets off a mechanism of cohesion, which reciprocally and multi-directionally involves every subject internal to the company, that is: the partners, the administrators, the executives, the managers, and the staff, to name a few. The emphasis is not on philanthropy but on sharing, in that each person gives and receives with equal dignity .

EoC companies are “a life of Communion in which the Poor are active participants.” Those who receive help are not considered “assisted” or “beneficiaries.” Rather, they are regarded as active participants in the project, all part of the same community, who also live the “culture of giving” (Bruni and Uelmen, p. 653) . The Economy of Communion entrepreneurs are not considered as “the rich” who share their surplus; rather, they are the first to live poverty, in an “evangelical” sense. This is because of their readiness to put their goods into communion and to face, out of love, the risks of business (Gui 2003) .

These are not companies whose ultimate objectives are solidarity; their goals are to help the poor and the “new” culture they are promoting, which become the means of a broader objective, that of creating a universal “fraternity.” It is this aspect that distinguishes all of the other non-profit and social organizations, which are born from a solidarity-focused orientation that becomes their ultimate aim. The entrepreneur who founds an EoC company is prepared to put his creative talents and risk-taking ability into play for an end that surpasses the boundaries of his company, in that he finds himself having a plan for stakeholders that goes well beyond typical competitive and environmental factors (Freeman et al. 2010; Alford and Naugthon 2002) . Such a plan considers the poor at the core of the mission. “Providence” (the hidden partner) silently, yet inevitably, enters into his management; “providence” materializes in ideas and in the strategic and operational intuition that are thought of individually but also together with other interested subjects (Fiorelli 2002) .

EoC businesses are also “travel companions and activators” of all those initiatives not only in the economics field but also social and civil fields. They attempt to go beyond the borders that exist between profit-making companies and nonprofit-making ones through collaboration networks that highlight the particularities of both. At the same time, they determine a common basis that is placed onto the pillars upon which they are founded: dialogue, faith in humanity, and reciprocity (Bruni 2009; Argiolas et al. 2010) .

Moreover, we define them as companies that develop the “globalization of solidarity” (Gold 2004) since, considering the actual conditions of the countries wherein they operate, they have developed (or are developing) a model of growth and relationship that, while following the initial model in Brazil, adapts itself to competitive and environmental circumstances and situations specific to the area. Consequently, they give life to unique models for each country that are suited the specific local context .

3.5 The Role of Social Enterprises

Finally, we have to consider the role of social enterprises, which began to develop in the 1980s and have emerged as innovative third sector organizations—in the context of a dual transition from modern, industrial societies to post-modern, post-industrial societies—embodying a new entrepreneurial spirit with a social mission in the pursuit of a variety of social and economic aims (Borzaga and Defourney 2001; Evers 1995, 2004) .

The definition of social enterprise has come into use to distinguish—following a wide interpretation (Thompson and Doherty 2006) —the entrepreneurial forms with a social aim, generating benefits for the community (UNDP-EMES 2008) and characterized by a relevant degree of public benefit connotation from more traditional non-profit organizations. Yunus (2008, 2010) defines social business as a sub-category of social entrepreneurship that operates as a business, selling products and services to customers. He also proposes a model of social business that refers to profit-oriented companies, owned and controlled by disadvantaged. In this case, the social objective is that profits are distributed among the “social entrepreneurs” with the aim of reducing their poverty. The European Commission sees social enterprise as “an actor of the social economy whose main objective is not to generate profits for its owners or shareholders, but have a social impact” (EC 2012, p. 2). This definition includes both companies that provide social services to a vulnerable public (care for the elderly or disabled, inclusion, etc.) both inclusive businesses, which, by the production of goods or services, pursue an aim that is social in nature (i.e., social and professional integration through access to employment for disadvantaged people).

Though primarily responsible for the production and delivery of human services (i.e., care giving and job training), social enterprises’ managerial capacity, democratic internal structure, and emerging role as key interlocutors between diverse community members has drawn attention to their hybrid character (Evers 2004; Gonzales 2006; Austin et al. 2006) . Although scholars frequently underscore their value as social institutions, for the most part, research has focused on their economic and managerial properties in an attempt to gauge their comparative productive and economic advantages. In recent years, attention has also been paid to the way in which social enterprises influence the formation and accumulation of social capital (Evers 2001). Social enterprises are also appreciated as potential agents of empowerment for marginalized populations. Focusing on their contribution to social inclusion and on two key functions of social enterprises, social production, and social mobilization, they develop forms of empowerment critical to the fight against social exclusion: consumer empowerment and civic empowerment (Gonzalez 2007). For marginalized service beneficiaries, empowerment is a salient aspect of social inclusion since it connotes enabling individuals or groups of individuals to develop competencies or capabilities. As service-based institutions, social enterprises offer two basic mechanisms for empowering users. The first relates to their social production function through which they generate consumer empowerment. The second mechanism for empowering users relates to the social mobilization function. Based on an understanding of service users as a collective group of disadvantaged citizens, this dimension signifies the ability of social enterprises to overcome key cultural and psychological barriers to social inclusion. As such, it relates to civic empowerment, which constitutes users’ abilities to challenge underlying norms and rules of engagement that typically lead inequities and injustices to have a taken for granted quality .

The pursuit of public interest objectives determines organizational principles, which differ from for-profit firms in four main respects:

First, the founding aim (the principle underlying the start-up of social economy initiatives) is a response to an emerging need in society. Examples include France’s companies specializing in labor market re-entry, special-interest associations, and local neighborhood councils; Italy’s social cooperatives and social enterprises; Germany’s employment and training corporations; Belgium’s on-the-job training companies and workshops; the United Kingdom’s community businesses and community interest companies; and Canada’s community development corporations (Borzaga and Defourny 2001; Nyssens 2006) .

Second, the presence of allocation principles exist based on solidarity and reciprocity. As already emphasized, social-economy initiatives operate at least in part according to the principle of solidarity and reciprocity.

The third objective is the inclusion of participation modalities and a democratic decision-making process in the organizational structure. Democracy in the decision-making process refers theoretically to the rule of “one person, one vote.” This principle implies the primacy of workers or consumers over capital.

Fourth, there is a plurality of resources. Operating differently from for-profit and public organizations, social economy organizations must rely on different sources of revenue originating from the market, non-market, and non-monetary economy .

The role of these enterprises has become sufficiently large to form a new sector called the “fourth sector” (Fourth Sector Network 2009).Social enterprises orient the entrepreneurial fabric in the direction of the civil economy and contribute to the development of a more humanized economy (Zamagni 2007) .

4 Concluding Remarks

The objective of this paper has been to highlight the importance of a significant re-thinking of conventional business models. There are a growing number of companies that have profitably navigated these challenges, and the development benefits appear to have been relevant. Developing business and fighting poverty offers real opportunities for sustainable growth. While many questions remain to be answered, “We already have substantial information and experience at our disposal for how to integrate people living in poverty into value chains. Every company and entrepreneur has to learn their own lessons through trial and error to some extent. Thus, the learning journey continues” (Gradl and Knobloch 2010, p. 7) .

The business sector is widely acknowledged as a key factor in solving major global development challenges. Notions of how business can play this role have changed. The focus has shifted from purely philanthropic interventions to ways to adapt commercial practice, and form “do-no-harm” responsible practice to strategies that optimize positive returns for business and development. One of the most important innovations in this context has been the emergence of inclusive business models that involve doing business with low-income populations anywhere along a company’s value chain. Their incorporation into the supply, production, distribution, and marketing of goods and service generates new jobs, incomes, technical skills, and local capacity.

In BoP ventures, the notion of selling to the poor has been replaced by business approaches that suggest sustainable value creation, implicating the development of strategies that serve triple bottom line goals. These include economic, social, and environmental benefits. Even if the concept is unique, the practices of inclusive business can differ among one another.

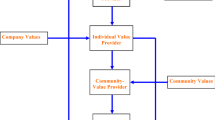

Basically, there are three common points. The first is that they are alternative approaches to business strategy and management for sustainable development that can follow both CSR and CSV orientations. Secondly, they are based on the concept of the poor as stakeholder and on the embeddedness into the socio-economic context in which they operate. Nevertheless, there is a substantial element of difference that lies in the ethical bases orienting their CSR and CSV strategies. Porter and Kramer speak about profits involving social purpose that represent a higher form of capitalism, one that creates a positive cycle of company and community prosperity: “creating shared value will be more effective and far more sustainable than the majority of today’s corporate efforts in the social arena” (2011, p. 75). They state that creating shared values represents a broader conception of Adam Smith’s invisible hand. The difference has to be considered between CSR and CSV in terms of citizenship, philanthropy, sustainability versus joint company and community value creation. Differences also have to be appreciated in terms of response to external pressures versus actions integral to competition and finally in terms of separate-from-profit maximization versus integral-to-profit maximization.