Abstract

“Team reasoning”—understood as fundamentally different from individual instrumental reasoning—has been proposed as a solution to a problem of strategic interaction discussed in game theory. But this form of reasoning has been deployed recently in philosophical discussion about shared agency and joint action, in particular to characterize the special “participatory” intention an individual has when acting with another. The main point of the chapter is that constraints on intending raise some challenges for this approach to participatory intention. If team reasoning rationally yields a participatory intention to A, it would require a belief or presumption on the part of the agent regarding what fellow participants will do—namely, that they or enough of them will also employ team reasoning. But what warrants this assumption? I contend that some ways of defending it are incompatible with what originally motivates team reasoning as a solution to a problem of strategic interaction. I will argue that if, as its proponents insist, team reasoning is to be fundamentally distinct from individual instrumental reasoning, then it must invoke a notion of a rational yet non-evidential warrant for belief. The distinctiveness of team reasoning would require, in general, that a team reasoner’s belief or expectation that other participants are also team reasoners is rational, but not acquired in the way that rational belief as it is usually understood should be acquired, that is, on the basis of evidence.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

What, if anything, distinguishes the intention I have when acting on my own from what we might call the participatory intention I have when acting with another? Some say that my participatory intention in what is variously called shared activity or joint action is an ordinary intention but with special collective content; others contend that the attitude itself is somehow primitively collective. My focus here is a recent suggestion that points instead to the distinctive form of reasoning that is said to issue in the intention. This “team reasoning”—understood as fundamentally different from individual instrumental reasoning—has been proposed as a solution to a problem of strategic interaction discussed in game theory. I will not attempt any detailed discussion of the theory of team reasoning itself; though I raise some questions about it, much of it will be taken for granted here. The focus, rather, is the theory’s deployment in philosophical discussion about shared agency and joint action. My main point is that constraints on intending make it difficult to understand just how team reasoning might be used to characterize the participatory intentions essential for shared activity. If team reasoning rationally yields a participatory intention to A, it would require a belief or presumption on the part of the agent regarding what fellow participants will do—namely, that they or enough of them will also employ team reasoning. But what warrants this assumption? I contend that some ways of defending it are incompatible with what originally motivates team reasoning as a solution to a problem of strategic interaction. I will argue that if team reasoning is to be fundamentally distinct from individual instrumental reasoning, then it must invoke a notion of a rational yet non-evidential warrant for belief. The distinctiveness of team reasoning would require, in general, that a team reasoner’s belief or expectation that other participants are also team reasoners is rational, but not acquired in the way that rational belief should be acquired, that is, on the basis of evidence.

1 The Basic Problem of Participatory Intention

What one is up to when, in the relevant sense, one is acting together with another is quite different from what one is up to when acting on one’s own. For example, going for a stroll with a friend is different from walking in proximity to a stranger whose path on a city street happens to converge with yours. And this is so, even if your walk is coordinated with the stranger’s insofar as the two of you keep some appropriate distance and don’t run into each other.Footnote 1 Now, if what one is up to is a matter of one’s intention (or the intentions with which one acts), then the distinction between shared activity and merely coordinated actions of individuals is at least in part a matter of the intentions of the individuals involved: there’s something about my intention when I walk together with a friend that makes it a participatory intention, distinct from my intention when I walk in proximity to and in some coordination with a stranger. What, then, is the difference?

One thought is that in shared activity what I’m up to involves more than just my own actions; I intend the entirety of our activity, J.Footnote 2 My intention concerns, for example, our walking together. For Bratman, this has to involve the idea of the intention that we J. This locution serves to highlight parallels Bratman sees between intention and the propositional attitude of belief. But if one finds this way of talking awkward, think of it alternatively in terms of an intention of the form: I intend to J with you. Either way we construe it, the proposal runs up against a number of plausible conditions on intending. For instance, many think that one can only intend one’s own actions.Footnote 3 Even if we try to take advantage of the alternative locution and insist that my J-ing with you is my own action, it is unclear whether I have the control or authority to settle or conclude that I will do it with you. Indeed, if I am in a position to form an intention and settle what we all do (or settle that I do this with you), then this suggests that I have authority or control over fellow participants—hardly compatible, it would seem, with the activity being shared.Footnote 4

Why not then attribute to a participant something more modest? The intention to do one’s part in shared activity does not encompass the actions of fellow participants. Thus, it doesn’t run afoul of the own action condition and entails no problematic authority over others.Footnote 5

But this doesn’t capture what it is that I’m up to in acting with you. Take the case of walking together. If we suppose that my part is simply to walk at a certain pace, then the proposal would be that I have an intention to walk at that pace. The problem becomes evident when we consider what happens when you stumble and fall. If my intention is simply to walk at some pace, I could very well continue walking and leave you in the dust, without stopping and helping you up. Indeed, my intention of walking at some standard pace is entirely consistent with attempting to trip you or otherwise undermining your contribution to what we’re doing. So, the intention understood in this thin sense doesn’t capture what the agent is up to. Even if nothing happens that would prompt me to leave you in the dust, etc., and our actions are coordinated without a hitch, the point is that on this thin understanding, the intention that is to represent what I’m up to in acting with you fails to rule out doing things entirely incompatible with shared or even merely coordinated action.Footnote 6

One might object that I’m not taking seriously the idea of doing one’s part in shared activity. So suppose we avail ourselves of a more robust conception of part, so that each participant intends to do his part in shared activity as such. This would appear to rule out attempts to undermine a partner’s contribution, and offers the prospect of capturing what an agent is up to in shared activity. But it creates another problem. It’s not clear that I can actually will my part so understood, if your contribution is not forthcoming.Footnote 7 My intention would seem to require that your contribution and our J-ing be a settled matter; but when was this settled? Doesn’t your being settled on it depend on my being settled?Footnote 8 How then could I rely on your being settled in order to form my intention? The intentions of the participants are supposed to settle the matter; but it seems that each of those intentions presupposes what they are supposed to accomplish.

To sum up: We understand what one is up to in shared activity in terms of one’s intentions. An intention concerning the entire activity does capture what I’m up to when acting with another, but seems to entail an authority over others incompatible with the activity being shared. We might instead opt for the strategy that appeals to the intention to do one’s part. But this strategy leads to a dilemma. Either we have a thin understanding of ‘part’, in which case we don’t account for what one is up to in shared activity. Whereas, a robust conception of part presupposes shared activity/intention in taking as settled the activity that the intention was supposed to establish. We might call this the Settling Problem, since a participatory intention seems to entail settling what another will do in a way that is incompatible with shared activity, or else problematically presupposes as settled the contributions of fellow participants.Footnote 9

Before proceeding, we might wonder whether participatory intentions could be understood in terms of the even more modest intention to do A in the hope that others will also join. That is, one intends to do A with the aim that we J, or as part of an attempt at getting us to J. But such an intention also fails to capture what I’m up to as a participant. An analogy might help illustrate the sort of point I want to make. Suppose that I’m making a rude gesture in your direction, and that you are facing me and see it. Then I’m offending you, and my intention is to do so. If I know you are facing away and can’t see it, then my intention would be not to offend you, but perhaps to let off some steam. It seems that there isn’t a common intention across the two cases.Footnote 10 One way to try to make sense of the rude gesture case (where I’m not sure which way you’re facing) denies, for example, that I’m intending to offend you, at least in the sense of intending according to which I can settle the matter. Rather, what I’m doing is at best a prelude to offending you. I’m taking a preliminary step, seeing whether what happens is that you’ll be offended, or that I’ll merely let off some steam. But taking this preliminary step to see what happens is hardly a commitment to what turns out to happen, hardly, for example, to will the offense. It’s quite different from what I’m up to when I make the gesture right in your face.

This point also applies to shared activity. Part of the problem here is that the project is that of defining or articulating the intention constituting the individual’s contribution to shared intention, and his or her involvement in joint activity. An intention that doesn’t settle for me my involvement, that I see as something that may or may not lead to intention and activity that’s shared, hardly fits the bill. I suppose the thought is that the commitment to the activity comes from intending something that is aimed at the activity, where aiming doesn’t entail settling in the way that intention does. I worry that this doesn’t suffice for commitment, for one might aim at two different and incompatible ends, for example when one seeks to marry X, and also Y, thinking that this increases the chances of marrying only one.Footnote 11 To adapt the example for the shared case: X and I make plans to get married. I aim to do my part in X and myself getting married. But Y and I also make plans to get married. I likewise aim to do my part in that. I can aim for both of these things. But in aiming at these incompatible things, what I’m up to in either of the activities is fundamentally different from what I’m up to in intending and committing to only one of them.

2 Team Reasoning

But perhaps there remains a way of characterizing the intention to do one’s part that doesn’t presuppose shared activity as settled, but which captures the appropriate attitude the participant has to the activity. The approach I’d like to investigate appeals to the aforementioned theory of team reasoning emerging from a recent strand of the literature on strategic interaction. At least on some versions of this approach, nothing in the form and content of the participatory intention distinguishes it from an ordinary individual intention. What makes this sort of intention distinctive (and a candidate for capturing the difference between shared activity and merely coordinated individual behavior) is the special team reasoning that leads to it. We find this approach in Bacharach (2006), and taken up in Gold and Sugden (2007). Thus,

team reasoning was originally introduced to explain how, when individuals are pursuing collective goals, it can be rational to choose strategies that realize scope for common gain. But it also provides an account of the formation of collective intentions…it is natural to regard the intentions that result from team reasoning as collective intentions. (Gold and Sugden 2007, p. 126; see also pp. 110, 121)

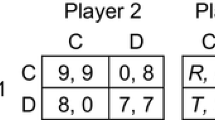

But what is this team reasoning in terms of which we’re to characterize participatory intentions? Consider the sort of scenario that has been used to motivate it, the two-person case of Hi-Lo (Table 17.1). In this game, each of the players has two options, A and B. For example, A could be the strategy expressed by the player as “I pick the King of Hearts”, and B the strategy expressed by “I pick the Three of Spades”. Each gets a prize if both pick the same option, but in one case (both adopt the same strategy A of picking a King of Hearts, say) the prize is much greater than the other (both adopt the same strategy B of picking a Three of Hearts). No prize is awarded if they don’t pick the same option. All this, and the rationality of each player (in the sense of maximizing individual expected benefit), is common knowledge.

Intuitively, the upper left box is the uniquely rational option. But the best reply reasoning of standard game theory does not favor this outcome over the lower right, which is also a Nash equilibrium. According to ordinary individual instrumental reasoning, one should act in such a way as to maximize one’s expected benefit, given one’s beliefs—among which are expectations about what others (in this case, you) will do. Thus, given that I believe that you (will) play A, I should play A; this would be my best reply to what you do. However, the same line of reasoning could be made in favor of playing B: given that I believe that you (will) play B, my best reply would be to play B. Thus, we don’t capture the intuition that both of us playing A is the only rational outcome of our interaction.Footnote 12

But why on earth would you play B? Isn’t it obvious that you should play A? Well, yes. But this is something that a theory of rationality is supposed to explain or account for. And an account in terms of individual rationality would be presupposing what it is meant to explain if it relies on the assumption that the other player would opt for A because it is obviously the rational thing to do.Footnote 13

So the upper left box is what we should rationally opt for, and it seems that ordinary instrumental rationality doesn’t secure that result. How then are we to explain the rationality of choosing in such a way that the upper left box is the outcome?Footnote 14

Team reasoning takes up this challenge. The basic thought is that the individual asks himself not

What is best for me given what you do?

but

What is best for us or the group as a whole?

This shift or enlargement of deliberative perspective leads to choosing the upper left box, in the sense of ranking it the highest.Footnote 15 , Footnote 16

For the purposes of this discussion, we can grant that the team-reasoning theorist is correct about the rationality of this choice in Hi-Lo.Footnote 17 Now, Bacharach reasons that it is not possible for me to intend or, as he puts it, implement this choice (2006, p. 63). That would be to settle more than I’m entitled to, since what I’ve chosen involves your actions as well as mine. What I’ve selected in answer to the question of what we should do leads me, rather, to intend my component or part of our action in the upper left box; in this case, it would lead me to intend to A. This intention concerning my own A-ing counts, in this scenario, as the collective option for me, i.e., it reflects what I’m up to in doing something with you. The intention’s status as collective and reflecting what a participant is up to stems from how the intention was arrived at. The act was rationally chosen in this situation because it generates the best outcome for everyone (Pareto optimal), as represented on the matrix, and that it was chosen by the individual as a response to the question of what we should do (what would be best for us).Footnote 18 The fact that an individual is to think in this team perspective—to see the options in this way, and to act accordingly—captures the sense in which the intentions that result are participatory intentions, which serve to distinguish shared activity from individual agency.Footnote 19

3 Does Team Reasoning Resolve the Settling Problem?

We’re investigating whether participatory intentions can be understood as the product of team reasoning. Now, does the attitude described as ‘that which issues from my team reasoning’ count as settling some relevant practical matter? It is important to ask this question because otherwise the attitude would not be the right intention, or not even count as an intention at all. Either way, the proposal would fail to account for what one is up to in shared activity, given that what one is up to is understood in terms of one’s intention.Footnote 20

It appears that we have an intention here. Through team reasoning, I am able rationally to opt for A-ing. Further, as the matrix suggests, it seems that A-ing is something I am able to do irrespective of what you do. On the team reasoning view, when it comes to forming the intention after one has engaged in team reasoning, one just intends one’s own action (e.g. the A-ing that I would do in our both A-ing). The point is that I have control over what I do, so am able to settle that. This is what ensures that the settling condition is satisfied. Thus, my intention to A is rational and reflects what I’m up to in a way that appears not to run into the Settling Problem.

But I think that the problem here is that the matrix offers a misleading picture of how it is possible that I may be settled on A-ing (where A-ing is my part, or what I do, in the shared activity). If the other person doesn’t join in, then often there simply is no A-ing for one to do. Think of a case where A-ing is lifting my end of a heavy sofa that I could not budge by myself. Or, to draw on a cliché, think of dancing the tango. One can’t dance one’s part of a tango if the other person declines. One might go ahead and dance by oneself. Then again, one might perhaps skulk off to get a drink. Whatever one does, it is something that one does instead of acting on the original intention to do one’s part. That’s because what each of us does in the tango or the sofa-lifting (as the case may be) is interdependent with what the other does, and hence my intention to lift this end of the sofa or my intention to dance my part of the tango is interdependent with your corresponding intention. Dancing one’s part is not something I can settle (or be settled on) independently of you.

Although the table representing possible outcomes in Hi-Lo might suggest the possibility of A-ing in situations when others don’t join in as well as when they do, this is misleading. There may be a sense in which this is true in the card case of picking either a King or a Three.Footnote 21 But it’s not always true. As Bratman has emphasized in recent discussion, what intention one has often depends on the intentions of one’s partners.Footnote 22 In many scenarios for which we might construct the sort of table of options that we have for Hi-Lo, the intention to play the Hi strategy (A) is not guaranteed to be available to me. Without knowledge or assurance that you have the corresponding intention, I am not in a position to form mine. So even though A-ing is my own action, whether I’m in a position to A is not entirely up to me to settle. One cannot intend A if it’s not something that one can thereby settle.

A clarification before proceeding. When I speak of the intention to A being interdependent with those of fellow participants, I don’t mean to deny the possibility of error, where I form the intention but my presupposition that you intend likewise and will join in turns out to be false. As with representational states generally, there is the possibility of things going wrong. Compare the case where I intend to drive to the store, but don’t realize that my car is broken: I have the intention, but its conditions for success are unsatisfied. Of course, once I learn that the presupposition is false and that you aren’t joining in or that my car is broken (as the case may be), I will revise the intention. But until I discover this, my intention to A in the context of shared activity is the same as the intention to A when there is no shared activity, except that the latter won’t succeed. In light of this, the initial point about interdependence should be understood as one about what one can rationally intend: I cannot rationally maintain my intention if I lack sufficient warrant for holding that the conditions for its success are in place.

Returning to the main thread, we might wonder what to say about some A-ing that differs from the tango or sofa-lifting insofar as it is possible for me to A even if others don’t joint in. Might we say that at least in these cases, team reasoning successfully addresses the Settling Problem? To see that a problem remains, note that the nature of the interdependence of intentions is usually not merely that of satisfying an enabling condition on what’s intended. There is also the thought that often there is no point to acting this way unless someone else is also participating. Take Bratman’s case of intending to leave town prompted by a desire to elope. Part of the point of my running away is that I am doing it with you. I do intend to A in the case where you join in, but I would intend no such thing if you don’t come along.Footnote 23 And this is typical of cases that are taken to demonstrate the need for team reasoning. Team reasoning doesn’t seem to address this sort of interdependence. If so, this would be a significant limitation for this way of characterizing participatory intention.

There are of course cases where one would intend to A irrespective of whether others will join in. For example, I’d be happy to go to the farmer’s market with you, but I’m fine going by myself if you’re too busy with other errands: I plan/intend on going in any case. Thus, some intentions are pitched at a sufficient level of abstraction that they will count as being acted on irrespective of whether others join in. Why, then, couldn’t the team reasoning strategy be used to arrive at some more abstract intention that could serve to capture participatory commitment?

One worry with this view is that it seems that not all cases of reasoning toward shared intention and joint action involve first formulating an intention and only subsequently figuring out whether to do it on one’s own or with someone else. Our walking together is not always an implementation of some prior or higher order individual or cooperatively neutral intention. (One might assume that there is always a more general intention because one subscribes to a picture of practical reasoning that has it starting with the most general ends, which are then rendered more specific.) But let us grant for the sake of argument that in the present case I do have an intention, for example, to go to the market, but have not yet filled in the details—including whether I’ll do it with someone or on my own. The second worry, then, is that if this is the sort of intention that’s defined by the team reasoning approach, then it’s not at all obvious that it depicts what I’m up to in shared activity. The picture, after all, is of an intention where I have not yet decided or committed to act with another. To address the settling problem by appealing to an intention that can be implemented irrespective of whether or not one acts with others is precisely what ensures that the intention won’t account for the “what it is that I’m up to” in acting with you. To get to the right sort of intention, one would have to so to speak descend to an intention more specifically implementing joint activity. But this was what couldn’t be settled by the individual.

So in many instances where others do not join in, either I would be unable to do my part or there would be no point in doing my part. Although there is a sense in which A-ing is up to me, A-ing-only-in-the-context-where-you-join-in is not something that I can settle. And it’s the latter attitude that is supposed to be the output of team reasoning, and which is needed to capture what I’m up to when I’m acting with someone. So if the team reasoning approach cannot handle the settling aspect of intention, then it hasn’t accounted for participatory intention.

The point might be put this way. By engaging in team reasoning, one is led to rank highest a certain cooperative outcome (the upper left box on our table). According to Bacharach (2006, p. 63), this will (rationally) lead one to intend one’s component in that highest ranked box. But the claim about intention formation does not follow from the claim about ranking. Bacharach (p. 136) argues that willing the outcome that’s best for the group requires that one will one’s actions that that outcome entails. That would seem to be so if the Means-End Coherence Principle is true. But it’s not clear that one is in a position to will the outcome of the group, rather than just rank it the highest. Ranking it highest doesn’t entail willing one’s part in it. There are many states of affairs that I value, but if I don’t think I can settle the matter and bring it about, then I’m not rationally required to intend means to bringing it about. The Means-End Coherence/Instrumental principle does require one to intend necessary means, but this only applies to intended ends, and not to some state of affairs that I rank the highest but for one reason or another do not intend.

4 The Distinctiveness of Team Reasoning

In this section, I consider two natural responses to the Settling Problem in light of the interdependence of intentions. I conclude that these responses are unavailable to the team reasoning approach because they each would undermine the case for team reasoning in the first place.

The first response is to think of participatory intentions as a kind of conditional intention. On this view, I intend our activity, or my part in it, conditional on you also so intending. This would avoid the Settling Problem, because such an intention does not presume to settle what others will do, nor does it presume that what they will do is settled.

But such a proposed amendment would not be welcomed by the advocate of team reasoning. To see this, consider the Hi-Lo scenario that motivates team reasoning in the first place. One thing that might plausibly be said about it is that each individual has a conditional intention to pick Hi (A, in the table above) so long as the other does as well. But of course, this would be an incomplete description because presumably each also intends to pick Lo (B) so long as the other does as well. Thus, interdependent conditional intentions do not offer an account of how one decides and settles the matter of what to do in the Hi-Lo scenario; at best it merely re-describes a problem situation that the team reasoning is meant to resolve. It is not surprising, then, that Bacharach explicitly criticizes such an approach.Footnote 24

Another familiar and natural response to the Settling Problem suggests that one’s participatory intention that we J (or that I J with you) is founded on a prediction about what others will do, or would do given how one acts. Now, one might think that this would be of use to the advocate of team reasoning. After all, things won’t go well for me when I use team reasoning and you don’t. If I could predict that you would choose Hi then I can be reassured in using it myself. However, this solution threatens to collapse team reasoning into ordinary individual instrumental reasoning, whereby I choose Hi based on my prediction that you will choose Hi, and my belief that this would maximize expected benefit. The Hi-Lo scenario is meant to motivate team reasoning as something distinct from ordinary individual instrumental reasoning. If it is to do so, then presumably we cannot merely on the basis of experience predict what the other person will do.Footnote 25 Otherwise, the rationality of picking Hi is accounted for in terms of ordinary individual instrumental reasoning. Thus, Bardsley (2007, p. 149) says “proponents of team reasoning explicitly deny that coordination is based on expectations about others’ actions.” He cites Sugden (1993, p. 87): “It is because players who think as a team do not need to form expectations about one another’s actions that they can solve coordination problems.”

Somewhat puzzling, however, is the position of Bardsley and, it seems, Sugden, regarding one’s belief or assumption that the others are also team reasoners. Sugden requires that “each member … has reason to believe that each other member endorses and acts on team reasoning …” (Gold and Sugden’s conclusion in Bacharach 2006, p. 168; see also Sugden 1993). Bacharach refers to this requirement as “Sugden’s Proviso” (p. 141). In an editor’s note to Bacharach’s text (p. 153, note 22), Sugden makes clear his own view that “If it is common knowledge that all members of the relevant group conceive of rationality in terms of group agency … then it is rational for each member to act according to the prescriptions of team reasoning.” Presumably, we may add: whereas, if there is common knowledge that each makes use of individual instrumental reasoning, then one should not be engaging in team reasoning. The point is that an expectation or belief about others being team members and engaging in team reasoning is crucial for team reasoning. In the same vein, Bardsley says:

For the intention [generated by team reasoning] to arise the agent must expect that the requisite circumstances obtain. The key circumstance for collective intention is that the agents constitute a team, implying that the other agents are fellow team members with reciprocal beliefs about the membership of the relevant others. That involves viewing them as disposed to act on a plan to bring about some goal, without making this conditional on the others’ actions, or else we are back into a coordination problem, but rather conditional on their team membership. (Bardsley 2007, p. 153; see also pp. 145, 150)

But it’s not at all clear why the belief that others are team reasoners is any less problematic for the advocate of team reasoning than the belief that others will act by doing A (picking Hi). After all, what good is the belief that another is a team reasoner if one cannot conclude that they will act on it and choose Hi? Whether it concerns how the other will act or whether the other is a team reasoner, the belief that would seem to be necessary for team reasoning to go through is the belief that the other will play Hi. But such a belief would render team reasoning otiose. For with the belief that the other will play Hi, or that the other is a team reasoner (and so will play Hi), one can simply apply individual instrumental reasoning in order to generate the response that we all think is intuitively rational—picking Hi.

Consider Gold and Sugden’s proposed schemas to articulate the rationality of team reasoning (at least on behalf of Bacharach). Their Schema 4 is meant to represent team reasoning from the perspective of an individual participant:

-

1.

I am a member of S.

-

2.

It is common knowledge in S that each member of S identifies with S.

-

3.

It is common knowledge in S that each member of S wants the value of U to be maximized.

-

4.

It is common knowledge in S that A uniquely maximizes U.

I should choose my component of A.Footnote 26

How are we to understand the premises in this schema? Gold and Sugden say, “Our basic building block is the concept of a schema of practical reasoning, in which conclusions about what actions should be taken are inferred from explicit premises about the decision environment …” (Gold and Sugden 2007, p. 121). This makes it sound as if an individual reasoner establishes the premises independently of and prior to engaging in the inference. But then the worry is, again, that the premises involving common knowledge might warrant the conclusion on the basis of ordinary individual reasoning; there would be no need to appeal to some special form of team reasoning.Footnote 27

5 Non-evidential Warrant

Suppose we agree with the advocate of team reasoning and think that this reasoning is distinct from individual instrumental reasoning, and necessary to account for what we think would be rational to do in the Hi-Lo situation. Then we need to take the same attitude toward the belief that the other is a team reasoner as we do toward the prediction that the other will play Hi. That is, we must deny that either of them is available as an independent resource for solving the Hi-Lo problem. Otherwise, the problem will not demonstrate the need for team reasoning as opposed to individual instrumental reasoning.

What should be evident now is the peculiar or distinctive character of the belief concerning fellow participants that’s presupposed in team reasoning (the belief, that is, they are also team reasoners and hence will opt as one does for Hi). The presupposition cannot be an ordinary belief or expectation, based on evidence, if team reasoning is to be distinct from individual instrumental reasoning. But if the presupposition is not an ordinary belief, how should we understand it?

One possibility is that the presupposition is a belief, but not one based on evidence; it’s just a brute fact of our psychology that we form such an expectation in response to certain situations. This might be suggested by Bacharach’s talk of framing, where depending on the situation one is triggered to see oneself as acting alone, or together with others.Footnote 28 Gold and Sugden remark that “whether the individual reasons as an individual or as a member of some larger group and, if the latter, which larger group she reasons as a member of are matters of psychological framing, not rationality” (Gold and Sugden, in Bacharach 2006, p. 164). But if we leave it at that, it’s not clear that we have vindicated the rationality of team reasoning. Rationality is normative, concerning what one in some sense should or ought to do; and this goes beyond a mere description of the psychological facts. It might be suggested in response that we can understand the missing normative element by understanding the psychological framing of a situation on externalist or reliabilist grounds.Footnote 29 For example, the tendency to frame the Hi-Lo situation so as to prompt team reasoning and the choice of Hi might be rationally vindicated simply by the fact that the players one generally encounters also see it this way, with the consequent favorable outcome. On this view, one’s belief that others are team reasoners receives a favorable epistemic assessment, even though one doesn’t have any reason or justification for it. Whether and how reliabilism handles a purported rationality constraint on knowing is a contested matter.Footnote 30 But even if something along these lines can be made to work, it’s not clear that what would be vindicated is team reasoning to the exclusion of ordinary individual instrumental reasoning, which after all could make use of the same externalist/reliabilist strategy to solve the Hi-Lo problem.

So how are we to regard the presupposition that others will also engage in team reasoning? It won’t turn out so well if one engages in team reasoning when others don’t cooperate. But I take it that if team reasoning is a valid form of reasoning that is distinct from individual instrumental reasoning, then it can be rational to adopt the cooperative intention even before it is settled in any ordinary evidential sense what one’s partner(s) will do. Of course, if the balance of evidence is that one’s partners won’t cooperate, one should not proceed. We might put the point as follows: team reasoning itself offers an answer to why we have the defeasible non-evidential expectation we do about the other parties: it’s a presupposition of a manifestly rational way of thinking (viz., team reasoning) that the other also thinks this way.Footnote 31

If team reasoning is a distinctive form of reasoning, the reasoner’s expectation regarding what others (or a significant element thereof) will do is just a matter of the rationality of the individual posing the question of what we should do in the situation and answering it by choosing Hi. But the latter is the central claim of the team reasoning proposal. That’s to say that the expectation regarding what the others will do is not independent of team reasoning.Footnote 32

So, the rationality of team reasoning is itself the answer to why one is non-evidentially warranted or entitled to the presupposition that fellow participants are team reasoners, and thus why one is in a position to form the relevant participatory intention. This will not impress those who are convinced that there is no need to modify standard game theory by revising the assumption of ordinary individual instrumental reasoning. But if you are amongst those who find compelling the arguments that traditional individual instrumental reasoning fails to account for the rationality of choosing Hi in the Hi-Lo scenario, you will also have to maintain that one’s (defeasible) entitlement to presuppose team reasoning in one’s fellow participants is part and parcel of the rationality of engaging in team reasoning and choosing Hi. We couldn’t engage in this manifestly rational reasoning and behavior unless we’re entitled to the (defeasible) presupposition that others will also reason, intend, and act this way.

***

To recap, the strategy of thinking of intentions as concerning one’s own action will not solve the Settling Problem that confronts accounts of participatory intentions in shared activity. And the team reasoning approach, at least as it has usually been presented, is no exception. This becomes clear once we recognize that normally in shared activity you only form participatory intentions when others would do so as well. So even if one is only intending one’s part and not what we all are doing, given this interdependence of intentions, how could one get into a position to intend? We’ve seen that the appeal to conditional intentions doesn’t solve the problem. And the appeal to the predictive strategy undermines the distinctiveness of team reasoning.

Team reasoning presupposes a belief that fellow participants are team reasoners. If we have any conclusive evidence for believing that they are, then we don’t need team reasoning. I conclude, instead, that if the rationality of team reasoning is manifest, then this should be demonstration enough of a non-evidential yet defeasible entitlement or warrant to think that fellow participants are team reasoners.

Notes

- 1.

Gold and Sugden (2007) give examples of individual actions that are coordinated (in the sense of being in Nash equilibrium), and yet intuitively do not count as shared activity. See also Bratman (2009) in this regard. But the difference is not just a third-personal fact about the nature of the coordination between individuals; it is also reflected in how it is for each participant, which is what the what one is up to locution is meant to capture. There is, moreover, the normative difference between the cases emphasized by Gilbert, who introduced this example. For recent discussion, see her 2009. I discuss the normative issue in Roth (2004).

- 2.

Searle (1990), Bratman (1992), and Velleman (2001). Bratman (1993) makes clear that a commitment on everyone’s part to the entire activity makes sense of the coordination; it would not be reasonable to rely on others the way we do in shared activity unless there is some such commitment. And the thought is that this commitment can be understood in terms of intention.

- 3.

- 4.

In the end, I don’t think that such an authority is incompatible with shared activity. See Roth (2013).

- 5.

- 6.

What about the intention not merely to walk at a certain pace, but to keep pace with you, where keeping pace is cooperatively neutral? It’s not clear that this captures what I’m up to when acting with you. Stalking involves the intention to keep pace with someone, and yet what one is up to when stalking someone is far from what one is up to in walking with them.

- 7.

This is over and above the worry that such a specification of the intention threatens circularity. The circularity worry is that an account in terms of the robust intention presupposes an understanding of the concept of shared activity which, if not the very notion we’re trying to elucidate, is awfully close (Searle 1990, p. 405).

- 8.

I don’t mean to suggest that nothing can be said to address this problem. For example, perhaps I can form the intention because I predict your contribution. See below. I discuss my concerns with the predictive strategy more fully elsewhere.

- 9.

See Velleman (1997).

- 10.

My intention to move my arm just so, when prompted by the intention of offending you, is quite different from my intention of moving my arm the same way when prompted by the intention to let off steam.

- 11.

Bratman (1987).

- 12.

Unless, as Gold and Sugden (2007) point out, we supplement standard game theory with assumptions regarding imperfect rationality (see also Bardsley 2006, p. 147). E.g. I think you are as likely to play A as to play B, so maximizing leads me to pick A. But it’s odd to have to appeal to the idea that you’re so irrational as to be as likely to pick A as you are to pick B. A further thought would be that I remain entirely agnostic about what you will pick (as was suggested by a referee). Wouldn’t maximizing expected benefits then point me to pick A? No, because I wouldn’t have any expected benefit. If I’m truly agnostic about what the other person will do, then I should be agnostic about what the expected benefit will be.

- 13.

See Bardsley (2006, p. 147).

- 14.

Actually, one figure in the team reasoning literature, Sugden, doesn’t seem to argue for the rationality of team reasoning. See Sugden’s editorial note 22 in Bacharach (2006, p. 141), where he rejects Bacharach’s interpretation of him.

- 15.

We need to understand the team reasoning approach correctly. If it is to address the problem of how individuals can come together to share an intention and act jointly, the team reasoning approach has to be addressed to the individual: it’s an account of how the individual reasons toward the intention that might represent her commitment to shared activity. Some presentations of team reasoning occasionally sound as if the question, what should we do? is entertained not by an individual but by the entire group or group-like entity comprising the individual participants, where it’s unclear what implication this is supposed to have for the rationality of each of those participants.

- 16.

- 17.

Regarding the assumption of rationality: in the philosophy of action, intentional action is tied to rationality; intentional action is understood as acting for reasons and explained in terms of reasons (Anscombe 1963; Davidson 1963). Given this tradition, the goal is to understand shared activity as a form of rational action. So it wouldn’t do us any good if selecting the cooperative option weren’t rational. It would, in this tradition, be problematic if shared activity and interrelated structure of intentions couldn’t be rationally willed.

- 18.

I leave open the question of circularity, of whether the proposal smuggles in the notion of collectivity by invoking some robust conception of parthood that presupposes the concept of joint or shared activity.

- 19.

- 20.

The line of criticism to be pursued here is in the tradition of those given by Tuomela and Bratman, each of whom also draws on the distinctiveness of intention in questioning the team reasoning proposal. Tuomela (2009) focuses on schema 4 from Gold and Sugden (2007, see Sect. 5 below) as encapsulating the team reasoning proposal. He points out that the pro tanto considerations serving as premises in the schema are not strong enough to establish the all out conclusion needed for an intention in the conclusion of the schema.

Even if we set aside Tuomela’s worry and assume some sort of all things considered judgment can be secured by reasoning along the lines of Schema 4, it’s still not clear that the resulting judgment corresponds to an intention. My participatory intention might be to J, even though the value judgment via team reasoning regarding what we should do is some J’ distinct from J. To take an example from Bratman (Shared Agency), weak willed lovers might through team reasoning judge it best not to elope. But they elope regardless, each intending his/her part in it. The judgment not to elope may reflect what is best for us. But we nevertheless elope, and do so together, and we each have the corresponding participatory intention to elope. In assuming that valuing most the option of not eloping is or directly converts to the corresponding intention (of not eloping), the team reasoning proposal fails to appreciate how intending is distinct from valuing.

- 21.

In the case of the cards, it does seem that I can pick and intend to pick the King, irrespective of what you do. However, it is not clear that I can pick and intend to pick the King as part of each of us picking the King, or as a way of carrying out the intention to pick the same card as you (unless I have some reason to think that you’ll pick it as well). Picking the King because you are also picking it is not something I can do or intend without information about you also picking it.

- 22.

See Bratman (2014) on enabling interdependence.

- 23.

See Bratman (2014), on reasons-for interdependence.

- 24.

- 25.

That’s why team reasoning points to a solution even when what we have is a one-off interaction with individuals with whom we have not interacted previously.

- 26.

Gold and Sugden’s use of ‘A’ differs from mine in that for them it denotes the shared act, rather than just one’s component in it.

- 27.

This is especially so if we modify premise 3 as Tuomela (2009, p. 299) rightly insists we should. See note 20 above.

- 28.

See for example Bacharach (2006, p. 137) who refers to a theory of entification involving framing as psychological, drawing a contrast with a normative theory of rationality.

- 29.

See Bacharach (2006, pp. 143–44) for suggestive remarks here.

- 30.

- 31.

It’s not as if we have positive evidence for thinking that the other is a team reasoner; rather, it’s a presupposition that might be defeated. In contrast, the predictive view doesn’t seem to be committed to any thought about the rationality of fellow participants (although perhaps it may—in which case it would have to explain the rationality). That is, on the predictive view, one can base the requisite prediction on whatever evidence one may have about fellow participants, irrespective of whether one takes them to be rational or irrational. For example, maybe it’s just a matter of habit that the other person tends to behave as she does, and this is something I come to know through experience in observing her.

- 32.

Contrast the status of prediction for e.g. Bratman, where the warrant for prediction is based on one’s experience of what the other does. Bratman works in a different literature and doesn’t feel that we need to build our account of joint action around the special case of Hi Lo. Whereas, the team reasoning view thinks of this special case as definitive of shared agency, and thus having a significance that extends to cases where this sort of reasoning is not necessarily required for coordination.

References

Anderson, E. 1996. Reasons, attitudes, and values: Replies to Sturgeon and Piper. Ethics 106: 538–554.

Anscombe, G.E.M. 1963. Intention. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bacharach, M. 2006. Beyond individual choice. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bardsley, N. 2007. On collective intentions: Collective action in economics and philosophy. Synthese 157(2): 141–159.

Bonjour, L. 1980. Externalist theories of empirical knowledge. In Midwest studies in philosophy 5: Studies in epistemology, ed. P.A. French, T.E. Uehling Jr., and H.K. Wettstein, 53–73. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bratman, M. 1987. Intentions, plans, and practical reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bratman, M. 1992. Shared cooperative activity. Philosophical Review 101: 327–341.

Bratman, M. 1993. Shared intention. Ethics 104: 97–113.

Bratman, M. 2009. Modest sociality and the distinctiveness of intention. Philosophical Studies 144: 149–165.

Bratman, M. 2014. Shared agency: A planning theory of acting together. Oxford: Oxford University Press (in print).

Burge, T. 1993. Content preservation. Philosophical Review 102: 457–488.

Davidson, D. 1963. Actions, reasons, and causes. Journal of Philosophy 60: 685–700.

Gilbert, M. 2009. Shared intention and personal intentions. Philosophical Studies 144: 167–187.

Gold, N., and R. Sugden. 2007. Collective intentions and team agency. Journal of Philosophy CIV(3): 109–137.

Hurley, S. 1989. Natural reasons: Personality and polity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kutz, C. 2000. Acting together. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 61: 1–31.

Roth, A.S. 2004. Shared agency and contralateral commitments. Philosophical Review 113: 359–410.

Roth, A.S. 2013. Prediction, authority, and entitlement in shared acitiviity. Noûs 47(3): 1--27 DOI: 10.1111/nous.12011.

Searle, J. 1990. Collective intentions and actions. In Intentions in communication, ed. P. Cohen, J. Morgan, and M. Pollack, 401–415. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sugden, R. 1993. Thinking as a team. In Altruism, ed. E.F. Paul, F.D. Miller, and J. Paul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tuomela, R. 2005. We-intentions revisited. Philosophical Studies 125(3): 327–369.

Tuomela, R. 2007. The philosophy of sociality: The shared point of view. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tuomela, R. 2009. Collective intentions and game theory. The Journal of Philosophy 106(5): 292–300.

Tuomela, R., and K. Miller. 1988. We-intentions. Philosophical Studies 53: 367–389.

Velleman, D. 1997. How to share an intention. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 57: 29–50.

Velleman, D. 2001. Review of faces of intention by Michael Bratman. The Philosophical Quarterly 51(202): 119–121.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roth, A.S. (2014). Team Reasoning and Shared Intention. In: Konzelmann Ziv, A., Schmid, H. (eds) Institutions, Emotions, and Group Agents. Studies in the Philosophy of Sociality, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6934-2_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6934-2_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-6933-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-6934-2

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawPhilosophy and Religion (R0)