Abstract

Since last synthesized in the 1970s–1980s, the faunal record from modern excavations of Middle and early Upper Paleolithic occupations in Spain and Portugal has grown considerably. The overall picture is one of substantial continuity among the main game species exploited, and there is growing evidence for some marine resource exploitation in both periods. Significant use of rabbit developed in eastern Spain and Portugal earlier than previously thought, and there was apparently a reduction in competition between humans and cave bears in northern Spain across the MP-UP transition. Trends toward subsistence intensification show increases in both situational specialization and overall diversification during the Last Glacial Maximum, when Iberia was a refugium for plants, animals and humans, and in the subsequent Late Glacial phase, separating a period of low human population densities with reduced subsistence pressure during MIS 4-3 from one of locally high density and intensive faunal exploitation during MIS 2.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Spain

- Portugal

- Lagomorphs

- Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition

- Refugium

- Neanderthals

- Anatomically modern humans

- ungulates

- carnivores

- marine resources

- subsistence

Preamble

What follows is the result of a fairly exhaustive synthesis of the available archaeofaunal record for Iberia done by a prehistoric archaeologist who is a “consumer” of such information. The author, while he produces faunal data by excavating and collaborates with archaeozoologists, is not a faunal specialist himself. This review seeks to gather into one place the data as they stand published in 2010–2011 in a variety of forms (at best NISP and/or MNI), in diverse publication outlets (some very hard to access outside Spain and Portugal), and representing stratigraphic units (“levels”) of very widely divergent nature, albeit mainly from more-or-less modern excavations. It is extremely difficult to statistically compare faunal “assemblages” from different sites in whose excavations different criteria for defining “levels” may have been used and different methods (wet vs. dry) and mesh grades of screening, recovery and curation, undoubtedly were applied, and for the study of whose faunas different standards may have been used for identification (e.g., what was defined as being “unidentifiable”?) and quantification, as well as for “assemblage” creation (i.e., the lumping of finds from stratigraphic entities that may have represented palimpsests of greater or lesser temporal formation magnitude). Thus, these data sets are presented (hopefully for further—albeit cautious—manipulation by archaeozoological specialists) in an effort to expose the known facts to a wider audience and to suggest some broad, apparent trends. Such tentative conclusions are based on global—and only semi-quantitative—comparisons at the level of major blocks of cultural time (i.e., early and late Middle Paleolithic, Early Upper Paleolithic [Châtelperronian and Aurignacian] and Gravettian), covering the period before, during and immediately after the so-called Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition. The author has resisted reviewer suggestions to do further quantitative analysis and the interpretations have been kept modest. Thus the intention of this paper is to contribute facts (admittedly of unequal value) to the ongoing debate on the nature of this supposed cultural-adaptive revolution, with hints of both continuity and change in subsistence that must be interpreted in light of the Iberian environments and demography, as well as the possible dietary needs and capacities of the different hominin populations that likely were involved.

Introduction

The Iberian Peninsula was one of the last places where Neanderthals managed to survive (until sometime around 30–27 ka) and it was also a subcontinental region where early “Aurignacian” artifact assemblages seem to have been coeval with late “Mousterian” ones after ca. 40 ka. Current debates revolve around such issues as the exact timing of the extinction of the last Neanderthals, especially in Gibraltar, Andalucía and southern Portugal, the possible existence of late Mousterian “enclaves” in northeastern and north-central Spain, the hypothesis of an in situ development of an initial Aurignacian from the terminal Mousterian (notably at El Castillo Cave in Cantabria) (Cabrera et al. 2006, with references), and the controversial idea that certain anatomical traits of the Lagar Velho (Portugal) juvenile skeleton in a burial of Gravettian style with a radiocarbon age of 25 14C kBP may be suggestive of the presence of Neanderthal genes among anatomically modern humans in Iberia (despite the notable lack of any hominin finds associated with the Iberian Aurignacian) (Zilhão and Trinkaus 2002). This possibility has recently been strengthened by the finding of small percentages of Neanderthal genes among modern Eurasians (Green et al. 2010). In this context, interesting arguments are being made about, on the one hand, whether or not there were special ecological conditions in southern Iberia that favored the survival of the Neanderthals (e.g., Finlayson et al. 2006; d’Errico and Sanchez-Goñi 2003) until either environments or subsistence strategies may have caused faunal changes; and, on the other hand, whether or not there was some critical niche separation between the Iberian Neanderthals and the (putative) modern humans involving a nutritionally mediated reproductive advantage for the latter that ultimately allowed them to out-compete and replace the Neanderthals (Hockett and Haws 2005).

Much hinges on whether one can find evidence for significant differences in subsistence between the two populations that would directly or indirectly lead to the final success of “moderns” at least by Gravettian times and the demise of the “archaics”. Put simply, the question here is whether or not there was a sharp break in human subsistence between the Mousterian cultures of Neanderthals in Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 4 and early MIS 3 and those of the Early Upper Paleolithic (various facies of Aurignacian–hominin makers unknown in Iberia—plus Gravettian) in late MIS 3. The null hypothesis is that there was substantial continuity, as has been convincingly demonstrated for southwestern France by Grayson and Delpech (2002, 2003, 2006, 2008).

In examining this question, it is important to filter out aspects of change in the faunal record that might be due to evolutionary trends for which any hominin involvement is likely to have had no more than incidental impact. It is also important to keep in mind the role of raptors, bears and other carnivores in the creation and modification of ungulate and lagomorph bone assemblages in a site sample that is entirely composed of caves, especially in the earlier time periods under consideration, when the human presence and role was arguably relatively minor in many cases. A survey of the faunal evidence across the so-called Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition in Iberia is seriously hampered by the paucity of analyzed assemblages demonstrably dating to MIS 4 and early MIS 3, as well as by the geographically uneven distribution of assemblages even from later MIS 3. In many cases, there are so few sites with analyzed faunal assemblages that, if one or a small number thereof happens to be heavily dominated by a single species, the pooled faunal spectrum for the entire region and time period may be totally skewed, falsely giving the impression of regional subsistence specialization. (A case in point is the large quantity of chamois in Amalda Cave, the agency of whose deposition—hominin or felid—is current under debate.)

Although a credible argument can be mounted for human settlement of the high, relatively hostile environments of the Iberian interior during much of the Upper Paleolithic, this was clearly not always the case during the Middle Paleolithic. But studied faunal assemblages from those regions are simply absent at least at present, so the record for all periods under consideration here is essentially a peripheral one, based on sites that are coastal or peri-coastal, generally no more than a few tens of kilometers from the present (interglacial) shore. It is also a record that is very uneven. Although most of the faunal collections included here are from relatively recent excavations, surface areas or sediment volumes dug and methodologies of recovery and analysis all vary widely (some excavations were small pits, others large blocks). The degrees of expertise and effort of the many archaeozoologists/paleontologists who analyzed the collections reported here clearly varied, as did their methodologies. These facts lead to problems of inter-site comparability when comparing faunal assemblages.

I have made a modest attempt to standardize taxonomic names where possible (e.g., among the Rhinocerotidae and Equidae), opting for the nomenclature most generally used at present in the Iberian Peninsula. At some sites, many remains were only identified to family level, although one can generally assume that “Cervidae” mainly means red deer and “Capridae”, mainly ibex. The basic faunal data (derived from the primary references for each site, as listed below and in the References), on which the tables and discussion are based, are given in Appendices 7.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4.

MIS 3 and 4 Paleoenvironments

The Neanderthals evolved in Europe from Homo heidelbergensis in the period between ca. 300 and 200 ka and they survived the extreme environmental vicissitudes of the late Middle and early Late Pleistocene, including major, extreme glacials in MIS 8 and 6. MIS 5 was a generally warm, but highly variable interglacial that, after a long, saw-tooth cooling trend, terminated in a short and moderately cold glacial, MIS 4, between ca. 71 and 57 ka. MIS 3 was neither a classic glacial nor a full-fledged interglacial, but rather a highly variable interstadial, the last millennia of which were characterized by the onset at ca. 25 ka of a sharp climatic downturn that culminated in the Last Glacial Maximum early in MIS 2. The Neanderthals disappeared at the beginning of that downturn. A recent synthesis of paleobotanical evidence from Spain and Portugal by González-Sampériz et al. (2010, with extensive references; but see d’Errico and Sanchez-Goñi 2003 for alternative views on vegetation reconstruction) serves as the basis for the following characterization of MIS 4 and 3 vegetation in the peripheral regions of the Peninsula.

The narrow northern Atlantic strip of northwestern and north-central Spain (together with a small northwestern corner of Portugal and a thin band south of the Pyrenean crestline including extreme northeastern Catalonia) is the only region of the Iberian Peninsula that is part of the Eurosiberian biogeographic or ecological zone. From west to east, it consists of the modern cultural/administrative regions of Galicia (where there are no Middle or Early Upper Paleolithic sites with faunal remains), Asturias, Cantabria and Euskadi (Basque Country). The rest of Spain and (despite its bordering the Atlantic Ocean) most of Portugal (the southern and central regions being the only ones with sites of relevance to this discussion) fall within the Mediterranean biogeographic zone. This division also had a significant degree of relevance during Pleistocene times, both glacial and interglacial/interstadial.

Limited pollen evidence from Galicia shows the presence of heath and grasslands, but with both some deciduous trees (including several rather temperate taxa) and conifers during MIS 4, while charcoal from El Castillo Cave (Cantabria) revealed the presence of both Scots pine and birch and the more thermophile beech in the high-relief, north-coastal Atlantic region. MIS 3 witnessed pulses of woodland expansion in this region, punctuated by episodes of arboreal contraction into regional micro-refugia. The more wooded phases included the spread of deciduous forms of Quercus or birch, presumably depending on temperatures. Increases in deciduous tree and shrub taxa came at the expense of Scots pine. The downturn that led to MIS 2 saw increases in juniper and pine, as well as birch, but willow continued to grow along water courses. The vegetation was always a mosaic of open heath and grasslands and tree stands or woods of varying importance. This Atlantic oceanic region was always relatively humid even during colder phases, in striking contrast to much of the rest of the Peninsula.

For Portuguese Estremadura (south-central Portugal) we have very limited data only from MIS 3 (from wood charcoal at archaeological sites). They suggest the presence of open steppes and heaths, but with stands of deciduous oaks, as well as maritime or stone pine.

Turning to the Mediterranean regions of Spain, there is pollen evidence for MIS 4 and early MIS 3 for the northeast from the Abric Romaní (Barcelona, Catalonia). Pine dominates throughout, but always accompanied by juniper, birch and a variety of rather temperate deciduous trees. Arboreal pollen fluctuates between 40 and 60 %. MIS 3 evidence from L’Arbreda (Gerona) and Lake Banyoles confirms the substantial presence of trees, as well as a fluctuating extent of open vegetation in Catalonia. The evidence from several sites in Aragón (interior northeastern Spain’s Ebro River Basin)—including Gabasa Cave (Huesca) indicates MIS 3 arboreal vegetation dominated by Scots pine and juniper, but with both evergreen and deciduous oaks, as well as a wide variety of other deciduous trees (including some quite temperate Mediterranean taxa such as olive). The vegetational mosaics of this period included varying amounts of steppe-like grasses, weeds and shrubs, including Artemisia, which often characterizes the cold, dry glacial phases in Mediterranean Spain. For the eastern and southern sectors (the regions of Valencia and Andalucía), the most substantial records are palynological and come from the Padul bog core and the cave of Carihuela, both in Granada, complemented by a few other natural and archaeological loci. MIS 4 shows the co-presence of both steppe plants and trees that are dominated by pines and junipers, but also include numerous more temperate taxa (various deciduous trees plus scrub taxa). The Mediterranean taxa clearly survived in refugia in these meridional, high-relief regions, despite the presence of cold, dry-loving plants. Such mosaics continued throughout MIS 3 (including in the record for the Cova Beneito archaeological site in Valencia, which also has wood charcoal assemblages, dominated by Scots pine and traces of juniper). In the far south, there is an overall trend for alternation between more steppe (with pockets of trees) and episodes of greater woodland cover, as attested in both pollen (mainly Padul and Carihuela) and charcoal records (including such key archaeological sites as Zafarraya, Bajondillo and Nerja in Málaga and Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar. “Disharmonious” floras—including both “cold” and “warm”, non-Mediterranean and Mediterranean taxa—characterize the southern Spanish refugia during MIS 3 and 4. This is corroborated by pollen records from marine cores in both the Alborán Sea (extreme western Mediterranean) and Atlantic margin of Portugal. Apparently there were no dramatic shifts between MIS 3 and 4 in Mediterranean Spain or Portugal, and even in North Atlantic (Cantabrian) Spain the differences in vegetation were only matters of degree in terms of open versus wooded environments rather than a sharp reversal. However d’Errico and Sanchez-Goñi (2003) have argued that there was a significant increase in desert-steppe vegetation in southern Iberia during the Heinrich 4 event, possibly making this region unattractive to herd ungulate grazers and hence to modern humans, leaving Neanderthals in place at least temporarily.

The Early Mousterian Faunal Record

There are very few archaeofaunal assemblages that can be credibly argued to date to MIS 4. These may include Level III in Teixoneres Cave (see Fig. 7.1 for locations of main sites with faunal assemblages), 40 km north of the city of Barcelona (Rosell et al. 2010). The base of this stratum is dated by uranium-series to 94.6 ± 3.2 ka, but the top is unconstrained (capping flowstone Level I is 14–16 ka). The others are Levels VI and V in Cova Negra (Valencia), which are argued on stratigraphic and geological grounds to have been formed under cold conditions (with gelifraction) corresponding to traditional Würm II (Villaverde et al. 1996), and El Castillo Levels 22 and 21 with ESR dates of ca. 70 and 69 ka respectively (Dari 1999). The rather vague term “Early Mousterian” is used here as a rough proxy for levels probably formed during MIS 4 (Table 7.1).

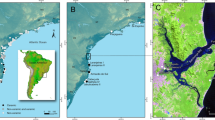

Map of the Iberian Peninsula showing the Eurosiberian and Mediterranean ecological zones, the principal sites mentioned in the text and relevant regions of Spain and Portugal. 1 Amalda, 2 Labeko, 3 Lezetxiki, 4 Axlor, 5 Arrillor, 6 Morín, 7 Venta Laperra, 8 El Pendo & Covalejos, 9 El Castillo, 11 Gabasa, 12 Teixoneres, 14 L’Arbreda, 16 Els Ermitons, 17 Romaní, 19 Cova Negra, 20 Les Mallaetes, 21 Beneito, 22 Zafarraya, 25 Gorham’s & Vanguard, 26 Columbeira, 28 Figueira Brava, 29 Val Boi, 30 Picareiro, 31 Anecrial, 33 Caldeirão. All are caves except 17 (rockshelter) and 29 (collapsed rockshelter & open-air talus slope)

The faunally richer Early Mousterian stratum at El Castillo (Level 22)—from Obermaier’s pre-World War I excavation, with all the caveats entailed by the inclusion of such an old collection along with more modern ones from other sites—is overwhelmingly dominated by horse, followed by red deer, with a scattering of other taxa [including a single element of Merck’s rhinoceros, as identified by R. Vaufrey and cited by Cabrera (1984) [see also Landry and Burke (2007) and Klein and Cruz-Uribe (1994) for analyses of Obermaier’s collections], but probably misidentified as an unlikely hippopotamus by Dari (1999) and—if it is the same bone in the IPH collection (a radio-ulna)—re-identified as bovine by Stuart and Lister (2007: 289)]. The sole carnivores are traces of cave lion and wolf (Table 7.1). The Teixoneres ungulate assemblage is nearly evenly divided, in order of importance, between red deer and horse, followed by ass, bovines/aurochs. Cave bear is well represented, as is lynx, and there are traces of hyena, beaver and porcupine. The two assemblages from Cova Negra both have very small numbers of remains from as many as 10 ungulate taxa. Wolf and lynx are present (one element each) in Level VI and both assemblages have relatively large numbers of rabbit remains, whose human agency would have to be demonstrated. There is really nothing in these collections suggestive of particularly cold conditions or the quantitatively significant persistence of “archaic” faunas. Undated Middle Paleolithic levels (said only to be of Late Pleistocene age and which overlie late Acheulean levels) in Cueva Hora (Granada) are dominated by horse (albeit in small numbers), followed by ass. There are even smaller numbers of red deer and ibex remains, also distributed widely among the levels. Finally there are a few, scattered remains of bovines, rhinoceros, wolf and lynx (Martín Penela 1986). Calculated globally, the Mediterranean Early Mousterian non-carnivore fauna spectrum is divided evenly (50/50 %) between ungulates and lagomorphs in NISP (Table 7.2).

The Late Mousterian Faunal Record

Late Mousterian levels (as defined here) pertain to the first 30 millennia of MIS 3. There are 20 assemblages from Vasco-Cantabria. Most are dominated by red deer remains, often followed by horse (Table 7.3; Altuna 1978, 1989; Altuna and Mariezkurrena 1988). One site, Amalda (in Guipúzcoa), has large numbers of chamois remains (Altuna 1990), but it has been argued that these may have been killed by carnivores (Yravedra 2007; pace Altuna and Mariezkurrena 2010), which are indeed very diverse and abundant in the level in question (VII). Other sites, Lezexiki (Level VI) and Morín (Level 17), are dominated by bovines, which are also very numerous in El Castillo Level 20 and Arrillor (Smk-I) (Castaños 2005; Martínez-Moreno 2005). Ibex is relatively common at Esquilleu (Cantabria), though the numbers are very small (Yravedra 2006). It is also dominant (and absolutely somewhat more abundant) in Venta Laperra, Axlor, Arrillor and Amalda. There are traces of rhinoceroses in several of the Late Mousterian assemblages (Covalejos, Morín, Arrillor, Axlor, Lezetxiki). Cave bear [possibly a facultative omnivore, although some (contested) stable isotope studies (e.g., Bocherens et al. 1994 vs. Hilderbrand et al. 1996; see Pacher and Stuart 2008 with references, for discussion) suggest it was mainly herbivorous] and numerous carnivores—notably wolf, fox and occasionally hyena and leopard—are also present in the Late Mousterian assemblages. There are very small numbers of hare remains in a few of the assemblages (Table 7.4); other rare small mammals include marmot.

The Late Mousterian of Eastern Spain (i.e., Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia) includes some assemblages that might pertain to late MIS 4 (i.e., Gabasa Levels g and h), but this is unproven so they are included here with MIS 3. All the Gabasa (Huesca, in pre-Pyrenean Aragón) levels have relatively large numbers of horse and ibex remains, and most (except the uppermost ones) have similar amounts of red deer (Blasco 1995). Chamois is constantly represented, but by only relatively small quantities. Very small amounts of boar, roe deer and aurochs are found in all levels, and traces of ass and rhinoceroses in most. Carnivores are fairly numerous and very diverse; they notably include wolf, hyena and lynx. The latter is interesting given the surprisingly high (for the Mousterian) representation of rabbit in all the levels. Based on taphonomic studies, including cut and gnaw mark analyses, it is likely that both hominins and carnivores (principally wolves and hyenas) were agents of accumulation and that carnivores also scavenged from human-hunted carcasses (Blasco 1995). The seven early-mid MIS 3 Mousterian levels from Abric Romaní (Barcelona) whose ungulate faunal assemblages have been studied are all dominated by either red deer or horse (Rosell et al. 2012; Fernández-Laso et al. 2010; Cáceres et al. 1998). Aurochs is generally present, but usually in only moderate amounts. Small numbers of rhinoceros remains are found in three levels and traces of chamois in only two. The mammalian faunas from late Late Mousterian Levels I and H in L’Arbreda Cave (Gerona) seem to have been more thoroughly studied and thus include carnivores, mustelids and lagomorphs (Estevez 1987). Red deer, with only moderate numbers, dominate both levels. Horse and ass also are substantially present and bovines (probably aurochs) are found in one. There are a few proboscidean remains. Cave bear is very abundant in the lower level (I) and there are especially many other carnivores in this level (wolf, hyena, fox, wild cat, lion). There are small numbers of hare remains, but no rabbit, despite the Mediterranean environment. The Mousterian strata (VI and IV) of montane Els Ermitons Cave (Gerona) are lacking in red deer and mainly (and logically) contain ibex, though the quantities are small (Maroto et al. 1996). Cave bear is very abundant and there are several remains of hyena, wolf, fox, leopard and lynx, again suggesting an alternation in use of this cave by Neanderthals, bears and carnivores.

Further south in Mediterranean Spain, the Late Mousterian assemblages of Cova Beneito are dominated by ibex, followed by red deer and horse, but all the counts are rather small (Iturbe et al. 1993). Rabbit bones are relatively abundant, but carnivores are virtually absent. In the MIS 3 levels of Cova Negra (most of whose ungulate remains were only identified to genus or family level), thar (Hemitragus) and other caprines (probably mainly ibex), horse and cervids (probably mainly red deer) are dominant in that approximate descending order (Villaverde et al. 1996). There are also some bovines (probably aurochs). Remains of rabbits are very abundant, but carnivores again are scarce. There are traces of rhinoceros.

The Late Mousterian data from Andalucía are dominated by Zafarraya (Málaga), which has some complex problems of stratigraphic mixing at least in its upper layers (Barroso et al. 2006a, b). The site is located high on a very steep cliff-side, so not surprisingly its assemblages are dominated by ibex remains, with only small numbers of chamois and red deer, and occasionally some aurochs, plus traces of ass and horse in one level (UD). On the other hand, carnivores are numerous and diverse [abundant leopard (also represented by coprolites) and dhole, plus hyena, wildcat, lynx, mustelids and some fox, plus brown bear in most levels]. Both carnivores and Neanderthals may have been the agents of ungulate accumulation and they alternated their occupation of the cave in each stratigraphic layer (Barroso et al. 2006a). Rabbit remains are abundant (NISP = 7,309; MNI = 118), but they are reported globally, not by level, and they are said to have been accumulated mostly by small-medium carnivores and owls, not by humans, at least in the Mousterian strata (Barroso et al. 2006b). The small Late Mousterian assemblage from Vanguard Cave (Gibraltar—a quintessentially steep, rocky habitat) is also dominated by ibex, followed by red deer from the then-dry coastal plain directly in front of the cave (Finlayson et al. 2006). There are also several carnivores and bear. Level IV in adjacent Gorham’s Cave (ca. 28 14C kBP) also has abundant ibex remains followed by red deer (NISP = 205 and 89; MNI = 13 and 7 respectively), huge numbers (NISP = 1,620; MNI = 97) of rabbit bones (not mentioned for Vanguard, perhaps for lack at present of a published study). There are small numbers of other ungulates and a wide variety of carnivores (notably hyena and lynx) and bear (Rodríguez et al. 2010). Obviously, the relative roles of Neanderthals and carnivores in the accumulation of rabbits in each site will have to be determined by careful taphonomic studies. Indeed, much work remains to be done to sort out the relative roles of hominins, carnivores and raptors in the accumulation of the remains of other mammals, birds and fish in caves such as those of Gibraltar. For example, Ibex Cave, high on the east-facing cliff of “the Rock” has Mousterian stone tools associated with uncalibrated radiocarbon dates of 35–40 14C kBP and a mammalian fauna dominated by ibex remains, along with rabbits, red deer, wolf, birds, voles, etc., but, unlike the cases of Gorham’s and Vanguard, there is “(n)o evidence of human activity on any of the… large, medium or small mammal remains” according to taphonomists Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews (2000: 174). Wolves, along with rock-falls, seem to have been the ibex assassins of Ibex Cave!

Presence/absence data from ≥54 ka (TL) Mousterian levels VII, VI a, VI (and possibly culturally poor level V) in Higueral de Valleja Cave (in the interior of Cadiz Province, north of Gibraltar) show a continuous presence of rabbit (also in the Gravettian and Solutrean levels). Red deer and horse are also ubiquitous and one Mousterian level each has traces of ibex, hare, wolf and wild cat (Jennings et al. 2009). Unfortunately there is no discussion of taphonomy in the publication, so one cannot judge whether the rabbits in any of the levels of this site were caught, processed or consumed by humans. Overall, the summed Mediterranean Late Mousterian non-carnivore faunas contain 79 % ungulate remains versus 21 % lagomorph ones (Table 7.4).

The Final Mousterian in Portugal has only three published faunal assemblages. Figueira Brava Cave is dominated by cervids (probably red deer), followed closely by ibex, with smaller equal numbers of aurochs and horse (Antunes 2000a). There are traces of boar, rhino and mammoth. Once again, carnivore remains are fairly numerous and diverse, including especially hyena. Rabbit remains are abundant and seem to have been consumed by Neanderthals in at least some cases. There are only four remains of land tortoise and two of pond tortoise in Figueira Brava (Antunes 2000b). Tortoises are not at all common in Iberian archaeofaunas—Middle or Upper Paleolithic—in contrast to some assemblages from the central and eastern Mediterranean basin studied by Stiner (Stiner 2001; Stiner et al. 1999).

Another Portuguese Late MP site is Caldeirão (Levels N-K), which is dominated by red deer (though the absolute numbers are fairly small), followed by horse, with even smaller numbers ibex and traces of several other ungulates (Davis 2002). There are small numbers of a wide variety of carnivores and a very large number of rabbit remains. Gruta Nova da Columbeira, Level 8, is also dominated by red deer, with small numbers of ibex, horse, aurochs and rhinoceros (Hockett and Haws 2009). Hyena is relatively abundant and here are traces of lynx, wild cat and wolf, and brown bear. The presence of rabbit in the Columbeira Mousterian is undocumented in the sources available to me at least. Overall, the Portuguese Late Mousterian non-carnivore spectrum is heavily dominated in terms of NISP by lagomorphs (92 %) versus ungulates (8 %). Rabbits as supplementary hominin food clearly preceded the UP.

Marine Resource Exploitation in the Late Mousterian

While it is true that many MIS 4 coastal plain sites are now drowned as a consequence of interglacial sea level transgression, there is no meaningful evidence of Mousterian exploitation of marine resources at coastal sites during MIS 3 in Vasco-Cantabria. [Such exploitation actually seems to have begun on a significant basis ironically during the Last Glacial Maximum (Solutrean period), when a key site for such evidence, La Riera Cave (eastern Asturias), would have been at least a couple of hours’ walk from the shore as opposed to the present-day half-hour (Straus and Clark 1986). This is paralleled by the sequence at Nerja Cave in Málaga (Aura et al. 2001).] A case has been made by Finlayson et al. (2006) and Stringer et al. (2008; see also Carrión et al. 2008; Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews 2000) that Neanderthals in Gorham’s and Vanguard Caves in Gibraltar exploited marine resources, namely mollusks, fish, seals and dolphins. This sort of argument had been made long ago at nearby Devil’s Tower by its excavator, Garrod et al. (1928), although doubt has been cast by Freeman (1981) on the anthropogenic origin of at least most of the marine mollusks found in (Last Interglacial) beach sands at that site, while noting that some are burned. Likewise, Klein and Steele (2008) contest the significance of the total of 149 shells, five seal bones, three dolphin bones and three fish bones from Gorham’s and Vanguard, arguing that even if collected (and in some cases of shells, burned) by Neanderthals, the remains are so few as to be nutritionally meaningless. There is no evidence that the seal and dolphin remains were not simply picked up as curiosities, even if they may have had some attached meat at the time. At any rate, these caves, currently directly on the shore, were never very far from the littoral [about 3–4 km during the Late Mousterian (Barton 2000) even if some of the mollusks came from an estuary in the present Bay of Algeciras], so the presence of at least many of these remains (and those of birds, which are diverse and abundant in all the Gibraltar caves) could be “natural”. The Humo Caves, directly on the northern shore of the Bay of Málaga and very near present sea level, have also yielded relatively abundant marine mollusks from undated Mousterian levels (Cortés 2007a: 48; Cortés et al. 2008: 2183). Their human agency remains to be demonstrated. Similarly, there are some marine molluscs in Last Interglacial deposits of Bajondillo Cave, near sea level on the western shore of the Bay of Málaga (Cortés et al. 2008: 2183)—agency unknown.

The Late Mousterian horizon (Level 2, dated to 30 14C kBP) of Figueira Brava Cave, right on the present Atlantic shore at the mouth of the Sado River estuary, yielded numerous mussel and limpet shells and crabs, as well as smaller numbers of a variety of other mollusks. Evidence of breakage is interpreted by the analyst (Callapez 2000, see also Antunes 1990–91) as indicative of human exploitation. A few marine mammal remains (one ringed seal ulna and 6 vertebrae from a common dolphin, both of which of course could have been beached animals) have gnaw- or cut-marks (Antunes 2000c). Given the site’s location, the molluscan collection is deserving of quantification and taphonomic re-analysis. A few marine mollusks have also been found with poorly known Mousterian materials in the Ibn Ammar caves on the Portimão estuary of the Algarve (southernmost Portugal) and (also from old excavations) in Furninha Cave on the Peniche Peninsula of western Portugal (Bicho and Haws 2008). Small animal foods were clearly of some significance (albeit limited in absolute terms) in Neanderthal diet in Portugal probably in the form of (seasonal?) pulses. This pattern seems to have been widespread throughout the eastern Mediterranean basin and in advance of the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition, although all r-selected animal foods (shellfish, lagomorphs) obviously increased in relative importance with higher Upper Paleolithic human populations (see Stiner 1994, 2001).

The Aurignacian and Other Early Upper Paleolithic

Clearly, the general interest of this survey is to see if there are any notable differences in archaeofaunas between those (presumably at least in part) obtained by Neanderthals and those obtained by the earliest Upper Paleolithic people, who are generally assumed to have been Homo sapiens sapiens (though this has not been demonstrated on the Iberian Peninsula, and not really well elsewhere in Europe either, for that matter).

The Early Aurignacian levels of El Castillo (18c and 18b of the new excavations) have very large numbers of red deer remains, swamping the nonetheless substantial amounts of chamois, and aurochs (Dari and Renault-Miskovsky 2001). There are smaller numbers of roe deer, ibex, horse, rhinoceros, mammoth and a trace of boar in the latter level. Carnivores are not common—just a few wolf, hyena and leopard remains in one or both levels—plus small amounts of brown bear. The dramatic quantity of and apparent specialization in red deer is obviously a novelty compared with the Mousterian faunal assemblages from the Cantabrian region (Table 7.5). Whether this is the result of a decline in the relative abundance of horse and an increase in red deer in the region due to climatic and vegetational changes in late MIS 3 and/or changes in human hunting strategies and practices is unknown. This is a key question to be resolved. Red deer is also relatively well-represented in all the Châtelperronian and Aurignacian levels at nearby Cueva Morin, but in nothing like the numbers found in El Castillo (Altuna and Mariezkurrena 1988). Small numbers of roe deer, bovine and horse remains round out the Morín EUP assemblages (Altuna 1972; Quesada 2006). There are virtually no carnivores (one item each of fox and wild cat in only Level 6, the uppermost Aurignacian). The Basque Country site of Labeko Koba, with a modern excavation and full publication, yielded a massively red deer-dominated Châtelperronian level (IX inf.), which also had large numbers of horse and bovine remains (Altuna and Mariezkurrena 2000). There are a few reindeer remains. Hyena is relatively abundant and there are traces of fox and cave bear. The same red deer-dominant pattern holds in the culturally indeterminate level (IX sup.), but there are small numbers of other ungulates [Megaloceros (extinct giant elk), roe deer, boar], a substantial number of rhinoceros remains, a few of mammoth and the same carnivores (hyena being even more numerous). The Proto-Aurignacian and Early Aurignacian levels at Labeko have far fewer red deer and horse, but many bovines and consistent presence of chamois. Some of the levels have traces of wooly rhinoceros and others of mammoth. The oldest Proto-Aurignacian level (VII) has very large quantities of cave bear and hyena remains. Fox is well-represented throughout, and some levels have traces of wild cat. The cave clearly saw alternating use among humans, bears and hyenas and the latter must have been carcass (i.e., bone) accumulation agents. Humans were not yet permanently in control of at least this cave.

In Catalonia, at L’Arbreda Cave, red deer bones (albeit all in rather small quantities) alternate with bovines, horse and ass for the “number one” position in terms of NISP in the two Late Aurignacian levels and there are traces of rhinoceros and mammoth in one level each (Maroto et al. 1996). The older of the two levels has a very large quantity of rabbit remains (with far fewer in the upper Aurignacian level). There are small numbers or at least traces of fox, lynx and hyena. The upper level yielded a large number of cave bear remains. Again, this cave may have been occupied by humans and cave bears on a “time-sharing” basis. The data are not all systematically presented for the three Aurignacian levels of Cova Beneito (Iturbe et al. 1993; Pérez and Martínez 2001). Globally, the dominant species is ibex, followed by red deer and then horse. There are traces of roe deer and boar. The number of rabbit remains rises steadily from the oldest to the youngest of these levels, attaining an impressive number (NISP = 1,534) in the Late Aurignacian one (B) (only to more than double again in the Gravettian level (B7) (Table 7.6). Together with the rabbits are small numbers of lynx remains in the upper two Aurignacian (and Gravettian) levels. This might suggest that humans were not the only rabbit-killers at the site in the EUP. Rabbit is also numerically dominant in the Aurignacian level (11) of Les Mallaetes, while ungulates are very scarce (small numbers of red deer, ibex and horse) (Davidson 1989). Carnivores are absent from the list.

The ambiguous (possibly mixed and contradictorily dated) EUP (?) levels in Zafarraya are heavily dominated by ibex (not surprising given the site’s cliff-side location), with only traces of red deer, chamois and horse (Barroso et al. 2006a, b). (The large numbers of ibex remains from Zafarraya swamp and thus distort the combined ungulate assemblages for both the Late MP and EUP of Mediterranean Spain, which is unfortunate given the chronological ambiguities of some of its levels.) Once again, carnivores (leopard, wild cat, dhole, hyena, fox) are relatively common, though bears are now absent. The cave continued to serve as a carnivore lair when not being used by humans. There are no other data from Andalucia—and none at all that are clearly Aurignacian, with the exception of Bajondillo Cave in Torremolinos (Málaga). This site has an apparent late Aurignacian component, radiocarbon dated to ~34 14C kBP, with small numbers of marine mollusks (as in the underlying Mousterian and overlying Gravettian levels) (Cortés 2007a). No other faunal information has yet been published for this important site—possibly the southernmost Aurignacian locality in Western Europe.

The same is true for Portugal. Caldeirao Cave (Estremadura) has an indeterminate EUP level (J), whose small assemblage is dominated by red deer, followed by ibex and boar, plus traces of boar, roe deer and chamois (Davis 2002). There is a very large number of rabbit remains (1,551), plus a large variety of carnivores and brown bear, all represented by very few remains. Human agency for the rabbit bones is possible, if one extrapolates back from what is known from the LUP assemblages (Hockett and Haws 2002). A possible EUP level in Picareiro Cave, also in south-central Portugal, is said by Hockett and Haws (2009) to have red deer, rabbit and hedgehog, but no quantities are yet published for this important, carefully excavated site.

Observations on Rabbits as Human Food

Globally, the EUP ungulate/lagomorph ratios for Mediterranean Spain and Portugal are 28/77 and 8/92 respectively. Portugal continued to be “the land of the rabbit”, as it had been in the late Mousterian. Can one presume the existence of nets and rabbit drives? Even so, obviously it took many rabbits (especially with their lean meat) to equal a single red deer in terms of nutritional value to the hunter-gatherers (Speth and Spielmann 1983: 3, 4; but see Hockett and Haws 2002; Hockett and Bicho 2000; see also Broughton et al. 2011 for a theoretical discussion of the relative importance of large body size prey relative to small ones like lagomorphs, with examples from the American Great Basin). A major practical problem, especially among Iberian sites that are almost all caves (not kill-sites), is the likely under-counting of large mammals by NISP since these game were field-butchered before only certain selected parts were brought back to residential sites (whether long- or short-term). This contrasts with the probable complete transport of rabbit carcasses back to such sites for processing and consumption, thus “inflating” the rabbit counts relative to the ungulate ones based on NISP. This is a case where comparison between animals of such widely divergent body sizes could be done more accurately by using MNI, which is unfortunately not often given for rabbits. Naturally, a secondary use for rabbits would have been their pelts. The point here is that in those Iberian regions where they were abundant (and perhaps red deer less abundant than in humid, plant food-rich Vasco-Cantabria), rabbits were a secondary food resource for hominins from at least Late MP times onward, though increasing in the Middle and Late Upper Paleolithic. Whether this increase reflected increased human subsistence stress and/or the development of more efficient methods and technologies for mass rabbit slaughter remains to be shown.

The Gravettian

Late MIS 3 is represented by a number of Gravettian levels in the various Iberian regions, beginning ca. 28 ka. Some of these assemblages (the most recent ones) can have been formed near the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum, some 12,000–19,000 years after the so-called Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition. There are modern-quality, published Gravettian faunal assemblages from only two sites in Vasco-Cantabria (Table 7.7). At Cueva Morín the three Gravettian assemblages are heavily dominated by red deer, with moderate numbers of roe deer, bovines, and horse, plus traces of boar, chamois and mammoth (1 item) (Altuna 1972, 1978; Quesada 2006). There are traces of wolf, fox, hyena, wild cat, leopard, but no bear. There are also a few hare remains. The Amalda Late Gravettian levels are very heavily dominated by chamois (argued in a reanalysis by Yravedra [2002; but see Altuna and Mariezkurrena 2010] to have been accumulated by carnivores, but nonetheless very strongly swamping and distorting the published Gravettian ungulate record from Vasco-Cantabria), with large numbers of ibex and red deer, plus traces of boar, roe deer and reindeer. The older of the two levels (VI) has a large number of horse remains, while the younger one (IV) has only a few. Carnivores are diverse and sometimes (wolf and especially fox) abundant. The impressive roster of carnivores plus bears strongly does suggest a major role for these agents of accumulation, with humans as only part-time residents of the cave and hunters of some of the ungulates. There are only traces of hare.

In Catalonia, horse dominates one of the three Gravettian levels (E) in L’Arbreda, followed by red deer (Maroto et al. 1996). All the Gravettian levels have those species plus small numbers or traces of ass, boar, chamois and aurochs. There is one proboscidean remain. One of the levels (F) has a large number of cave bear remains and all of them have traces of a variety of carnivores. Rabbits are very abundant and increase through time, certainly due to human predation. South of Catalonia, in Valencia, Cova Beneito Level B7—Gravettian—is roughly equally dominated by ibex and red deer, followed by horse (Iturbe et al. 1993; Pérez and Martínez 2001). There are only traces of a few carnivore species, but rabbits are very well represented (NISP = 3,625), no doubt killed by humans. The very small Mallaetes (Valencia) Gravettian (Level 10) assemblage is dominated by red deer and rabbit (Davidson 1989). The Gravettian levels in Les Cendres Cave (Alicante) have abundant rabbit bones with considerable evidence of butchery by humans (Table 7.8; Pérez Ripoll 2006).

Nerja Cave, on the shore of Málaga, saw its first marine and terrestrial mollusks (mostly Iberus) appear during the pre-Magdalenian (ca. 24–17.5 14C kBP) levels of its Vestibule area. There are small numbers of limpet and mussel shells in the Gravettian levels dated between 25 and 21 14C kBP (Cortés et al. 2005). Rabbit remains are also present in the late EUP and Solutrean levels. Human agency for these is claimed on the basis of some taphonomic analyses (Aura et al. 2002). Nerja was never more than 5–6 km from the glacial shore. But it was in the Magdalenian that full-scale, ocean fishing began (Aura et al. 2001). The pre-Magdalenian and Magdalenian ungulate faunas of Nerja are overwhelmingly dominated by ibex—not surprising given its location at the foot of a 1,500 m-high mountain chain that plunges straight down to the Mediterranean shore. There are also some marine molluscs in ~24 14C kBP, cold-climate Gravettian Level 10 of Bajondillo Cave in Torremolinos (Málaga) (Cortés et al. 2008).

In extreme southwestern Portugal at the rather unique open-air, coastal plain site of Val Boi, the combined Gravettian assemblage (22–27 14C kBP) is dominated by red deer, followed by horse, then aurochs and ass, plus traces of boar, ibex, and a few carnivores (notably lynx)—possibly trapped for fur by humans (Manne and Bicho 2009; Stiner 2003). There are a very large number of rabbit remains (NISP = 2,802) which are anthropogenic in terms of their accumulative agency and intensive breakage. The Val Boi Gravettian component is distinguished by the presence of a very large number of marine mollusk remains (NISP = 8,286, with an MNI of 1,054), overwhelmingly dominated by limpets (Patella sp.), at a time when sea level was falling but had not reached its LGM low when the shore would be 15–20 km from the site (Manne and Bicho 2009, 2011). There is also a vertebra fragment from a small cetacean (Manne and Bicho 2009)—probably scavenged or collected as a curiosity on the shore.

Picareiro Cave and Anecrial Cave in central Portugal show evidence of human exploitation of rabbits with marrow extraction. The combined Gravettian of Picareiro has produced >3,000 leporid bones (and 220 bird bones) (Hockett and Haws 2009). In Anecrial Level I the rabbit NISP is 1,601 and in Gravettian Level J there is a hearth full of burned leporid bones (Hockett and Haws 2002). The Gravettian of Lagar Velho is also rich in leporid remains (NISP = 1,336; MNI = 76) (Hockett and Haws 2009). Rabbit drives were obviously growing in importance.

Overall, for Mediterranean Spain and Portugal respectively the ungulate/lagomorph ratios are 16/84 and 12/88 in terms of NISP. Throughout all time, there was a dramatic difference between the Eurosiberian (i.e., Vasco-Cantabrian) and Mediterranean eco-zones in terms of the abundance of rabbits and thus their exploitation by humans—whether Neanderthal or Cro-Magnon.

Discussion and Conclusions

The watchword for Iberian archaeofaunas throughout MIS 3 and 4 in Iberia is “continuity”. There are no major breaks either between the Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic or between each of the two phases of either major phase (i.e., Early and Late Mousterian or Aurignacian and Gravettian). The Iberian Peninsula, south of the Pyrenees and south of the Cantabrian Sea/Gulf of Gascony was and is significantly different from France, never having been a land inhabited by many “arctic” taxa during glacials. Even the narrow, oceanic Vasco-Cantabrian strip, the only region of Spain that belongs to the Eurosiberian ecological zone (the rest of the Peninsula being in the Mediterranean zone, as noted earlier), never saw large numbers of reindeer, woolly mammoth or rhino, arctic fox, etc. Muskoxen, saiga antelope [one bone in the early Magdalenian of Abauntz in Navarra was probably carried there across the Pyrenees as a curiosity from southwestern France (Altuna and Mariezkurrena 1996)] do not seem to have lived here ever or hardly ever (Altuna 1996; Alvarez-Lao and García 2010). Ironically, MIS 4 archaeological deposits have virtually no cold-climate ungulate fauna. For late MIS 3, ca. 35–25 ka—also ironically—there are mammoth remains in both archaeological and non-archaeological contexts in the South (respectively in Figueira Brava Cave and the Padul bog in Granada), as well as in a handful of sites in Vasco-Cantabria and Catalonia. Naturally, there is a caveat in that we have very few purely “paleontological” sites; almost all the large mammal faunal evidence comes from archaeological sites (in caves), where human selection was operative, although almost certainly other carnivores (hyenids, canids, felids) were also involved to varying extent as agents of carcass accumulation (Straus 1982; Lindly 1988; Blasco 1995; Yravedra 2002). Besides Padul, for example, there have been a few purely paleontological finds of isolated mammoths from other loci in Spain, but in LGM contexts. Mammoth could have been present in the open-vegetation environments of Last Glacial central Iberia, but the paucity of sites makes it impossible to judge its relative abundance. The big steppe-tundra beasts of Ice Age France “visited” Spain and Portugal only rarely in both Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic times—reindeer a bit more frequently, but only in the far north of the Peninsula—but all were rare sights for the hominin residents whoever they were. And it is likely that only the reindeer were their prey in any meaningful way, however slight and sporadic. On the other hand, as with plants, Iberia was clearly a refugium or reservoir for species such as boar, red and roe deer that re-colonized France during temperate times.

Although there is often more variability between sites of the same period than between different periods, it is generally the case that Mousterian sites have relatively more large and very large ungulates (bovines, horses and rarely rhinos) than do the EUP sites. There is some question, however, as to whether hominins were actually butchering whole rhinos, since the numbers of their remains are always extremely few, leaving open the possibility that rhino bones and teeth were collected (already “bare” of any meat) as oddities. The tendency toward specialization in red deer and/or ibex hunting [which became overwhelming in the LUP—Solutrean and Magdalenian (Straus 1977, 1992; Freeman 1973, 1981; Marín-Arroyo 2009a, 2010)] is already beginning to be manifested in a few MP and EUP assemblages (e.g., El Castillo). That specialization often becomes quite clear by Gravettian times, though there may still have been confounding factors (i.e., non-hominin carnivore agency) in final MIS 3 times.

There are a couple of clear biogeographic aspects to the record that separate Atlantic Vasco-Cantabria from the Mediterranean remainder of the Peninsula. One is the presence of ass in many Mediterranean sites of various periods, though it is never very abundant as human prey. The other is vastly more important: rabbits—never present in the Eurosiberian zone, but omnipresent (when included in the published faunal reports) in Mediterranean Spain and southern and central Portugal. Oryctolagus cuniculus is present as early as the Early Mousterian, although hominin agency needs to be rigorously demonstrated in each case [see, for example, the virtual exclusion of human agency in Zafarraya after taphonomic analysis (Barroso et al. 2006a, b)]. Late Mousterian and EUP levels in Eastern Spain often have very large numbers of rabbit remains and this species becomes even more important quantitatively in Gravettian levels, no doubt (despite their small mass and the leanness of their meat) contributing a critical part of hominin diet, perhaps during seasons of scarcity of red deer and ibex. Growing numbers of studies in Mediterranean Spain and Portugal demonstrate that rabbits were butchered (and presumably hunted in drives or other types of mass kills, using nets, rabbits sticks, etc.) and consumed by people, with ample evidence of cut marks and burning (e.g., Pérez Ripoll 2001; Hockett and Haws 2002). Such a supplementary specialization in rabbit slaughter may have been motivated by regional human population pressure and/or over-exploitation of larger game, despite the relatively low nutritional return from these lagomorphs vis à vis large-medium ungulates (mainly red deer, ibex). The environmental conditions of the Mediterranean eco-zone may have been less favorable to high red deer densities than those of the Eurosiberian zone, while favoring prolific rabbit populations, with their high rate of reproduction. Given the high potential returns (in terms of meat, fat, marrow, organs, hides and—from red deer stags—antler) from the hunting of Cervus and Capra, it is hard to understand why humans would invest a lot of time and effort in killing many Oryctolagus if the ungulate populations were large and accessible enough to fully satisfy human food (and other) needs year-round. All these animals are, after all, fast and require considerable planning, skills and specialized technologies for killing en masse. The growing focus on rabbits in Mediterranean Spain and Portugal throughout the late Middle and Upper Paleolithic suggests that the reverse may have been the case, as well as the obvious, namely that fast-breeding rabbits were very abundant in these environments.

There is no clear-cut evidence of a break in hominin subsistence patterns between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic or indeed between MIS 4 and 3 in the Iberian Peninsula. The archaeofaunas of the Early and Late Mousterian, Aurignacian and Gravettian show considerable continuity within each ecological region of the Peninsula. It was biogeography that was mostly driving the observed patterns of human hunting. As I have argued several times before (e.g., Straus 1977, 1992; Straus and Clark 1986), the really significant changes in subsistence seem to have taken place with the Last Glacial Maximum and Tardiglacial in the Late Upper Paleolithic (Solutrean and Magdalenian periods) and may have been responses to increased regional population densities more than to climatic/environmental changes (see Marín-Arroyo 2009b; Stiner 2001). The interest of this overview is the clear evidence that hominins [both Neanderthals, followed (presumably) by anatomically modern humans] were already beginning to exploit rabbits (and perhaps shellfish) in small quantities in Mediterranean Spain and Portugal. This was probably not demographically driven, although the vast increase in small-animal exploitation (terrestrial and marine, as well as birds) in the Solutrean and Magdalenian periods probably was. The parallelism in the significant development of marine resource exploitation during the Solutrean in both north Atlantic Spain and Mediterranean Spain and in Portugal is also clear. The significant differences between Iberia as a whole and France in terms of both Mousterian and Early Upper Paleolithic subsistence are also clear: Iberia—the southwestern refugium of Europe—was not a land of reindeer, woolly mammoths or rhinos. It was always (and still would be, without the vast ecological changes wrought by the spread of agricultural lifeways) the land of red deer and ibex, accompanied by roe deer, boar, chamois, aurochs, horse, ass, and rabbit, depending on the region. Though Iberia witnessed occasional incursions of “glacial” fauna from the North, it was from the Iberian refugium that France etc. were repeatedly recolonized by “temperate” faunas—and hominins.

There is clear evidence neither of “superior” EUP subsistence practices nor of a more nutritious EUP diet relative to the subsistence of Mousterian Neanderthals in Iberia, at least as one can perceive from the (admittedly low-resolution) faunal evidence. The “wild card” could conceivably be the use of plant foods, but there is certainly no EUP lithic technology suggestive of an increase in that aspect of diet. Intensification surely began in Gravettian times in some regions (notably southern Portugal), as indicated by bone grease rendering and shellfish collection at Val Boi, for example (Bicho et al. 2010a, b; Manne and Bicho 2009). By then [and based on the Lagar Velho child burial (Zilhão and Trinkaus 2002)] the human inhabitants of Iberia definitely were anatomically modern (though possibly Neanderthal-“tainted”) humans, and in some regions, such as Portugal and Mediterranean Spain—as in Italy or the Czech Republic—their numbers were growing. This is the crux of the story that would lead to the major changes that marked the second half of the Upper Paleolithic in Iberia (e.g., Straus 1993), with a ratcheting-up of regional subsistence intensification that included situational specialization and overall diversification of mammalian, molluscan, piscine and avian species exploited and sometimes over-exploited, heavy carcass and bone processing, as humans scrambled to feed more hungry stomachs.

References

Altuna, J. (1972). Fauna de mamíferos de los yacimientos prehistóricos de Guipúzcoa. Munibe, 24, 1–464.

Altuna, J. (1978). Los mamíferos de Cueva Morin. In J. González Echegaray & L. G. Freeman (Eds.), Vida y Muerte en Cueva Morín (pp. 201–209). Santander: Institución Cultural de Cantabria.

Altuna, J. (1989). Subsistance d’origine animale pendant le Moustérien dans la région cantabrique. In M. Otte (Ed.), L’Homme de Néandertal, Vol. 6, La Subsistance (pp. 31–43). Liège: ERAUL 33.

Altuna, J. (1990). Caza y alimentación procedente de macromamíferos durante el Paleolítico de Amalda. In J. Altuna, A. Baldeón, & K. Mariezkurrena (Eds.), La Cueva de Amalda (pp. 149–192). San Sebastián: Sociedad de Estudios Vascos.

Altuna, J. (1996). Faunas de clima frío en la Península Ibérica durante el Pleistoceno superior. In C. Rodríguez, P. Ramil-Rego, & M. Rodríguez (Eds.), Biogeografia Pleistocena-Holocena de la Península Ibérica (pp. 13–39). Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia.

Altuna, J., & Mariezkurrena, K. (1988). Les macromammifères du Paléolithique moyen et supérieur ancien dans la région cantabrique. Archaeozoologia, I(2), 179–196.

Altuna, J., & Mariezkurrena, K. (1996). Primer hallazgo de restos óseos de antilope Saiga (Saiga tatarica L.) En la Península Ibérica. Munibe, 48, 3–6.

Altuna, J., & Mariezkurrena, K. (2000). Macromamíferos del yacimiento de Labeko Koba. In A. Arrizabalaga & J. Altuna (Eds.), Labeko Koba (Munibe 52), (pp. 107–181). San Sebastian: Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi.

Altuna, J., & Mariezkurrena, K. (2010). Tafocenosis en yacimientos del País Vasco con predominio de grandes carnivoros. Consideraciones sobre el yacimiento de Amalda. Zona Arqueológica, 13, 213–228.

Alvarez-Lao, D., & García, N. (2010). Chronological distribution of Pleistocene cold-adapted large mammal faunas in the Iberian Peninsula. Quaternary International, 212, 120–128.

Antunes, M. T. (2000a). Ultimos Neandertais em Portugal: Evidencia, Odontologica e Outra. Lisbon: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa.

Antunes, M. T. (2000b). The Pleistocene fauna from Gruta da Figueira Brava: A synthesis. In M. T. Antunes (Ed.), Ultimos Neandertais em Portugal (pp. 259–282). Lisbon: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa.

Antunes, M. T. (2000c). Pleistocene marine animals. In M. T. Antunes (Ed.), Ultimos Neandertais em Portugal (pp. 246–257). Lisbon: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa.

Aura, J. E., Jordá, J., Pérez Ripoll, M., & Rodrigo, M. J. (2001). Sobre dunas, playas y calas. Los pescadores prehistóricos de la Cueva de Nerja (Málaga) y su expresión arqueológica en el tránsito Pleistoceno-Holoceno. Archivo de Prehistoria Levantina 24, 9–39.

Aura, J. E., Villaverde, V., Pérez Ripoll, M., Martínez Valle, R., & Guillem, P. (2002). Big game and small prey: Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic economy form Valencia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 9, 215–268.

Barroso, C., Bailon, S., El Guennouni, K., & Desclaux, E. (2006a). Les lagomorphes (Mammalia, Lagomorpha) du Pléistocène supérieur de la Grotte du Boquete de Zafarraya. In C. Barroso & H. de Lumley (Eds.), La Grotte du Boquete de Zafarraya (Vol. 2, pp. 893–926). Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía.

Barroso, C., Riquelme, J. A., Moigne, A.-M., & Banes, L. (2006b). Les faunes de grands mammifères du Pléistocène supérieur de la Grotte du Boquete de Zafaraya. Etude paléontologique, paléoécologique et archéologique. In C. Barroso & H. de Lumley (Eds.), La Grotte du Boquete de Zafarraya (Vol. 2, pp. 675–891). Seville: Junta de Andalucía.

Barton, R. N. E. (2000). Mousterian hearths and shellfish: Late Neanderthal activities on Gibraltar. In C. Stringer, R. N. E. Barton, & J. C. Finlayson (Eds.), Neanderthals on the Edge (pp. 211–220). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Bicho, N., & Haws, J. (2008). At the land’s end: Marine resources and the importance of fluctuations in the coastline in the prehistoric hunter-gatherer economy of Portugal. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27, 2166–2175.

Bicho, N., Manne, T., Cascalheira, J., Mendoça, C., Evora, M., Gibaja, J. & Pereira, T. (2010a). O Paleolitico superior do sudoeste da Península Ibérica: o caso do Algarve. In El Paleolítico Superior Peninsular: Novedades del Siglo XXI, pp. 215–234. Barcelona.

Bicho, N., Gibaja, J. F., Stiner, M., & Manne, T. (2010b). Le Paléolithique supérieur au sud du Portugal: le site de Val Boi. L’Anthropologie, 114, 48–67.

Blasco, M. F. (1995). Hombres, Fieras y Presas: Estudio Arqueozoológico y Tafonómico del Yacimiento del Paleolítico Medio de la Cueva de Gabasa I (Monografías Arqueológicas 38). Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza.

Blasco, R. (2008). Human consumption of tortoises at Level IV of Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science, 35, 2839–2848.

Bocherens, H., Fizet, M., & Mariotti, A. (1994). Diet, physiology and ecology of fossil mammals as inferred from stable carbon and nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry: Implications for Pleistocene bears. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 107, 213–225.

Broughton, J., Cannon, M., Bayham, F., & Byers, D. (2011). Prey body size and ranking in zooarchaeology: Theory, empirical evidence and applications from the northern Great Basin. American Antiquity, 76, 403–428.

Cabrera, V. (1984). El Yacimiento de la Cueva de “El Castillo” (Bibliotheca Praehistoria Hispana 22). Madrid: CSIC.

Cabrera, V., Bernaldo de Quirós, F., & Maillo, J. M. (2006). La Cueva de El Castillo: las nuevas excavaciones. In V. Cabera, F. Bernaldo de Quirós, & J. M. Maillo (Eds.), En el Centenario de la Cueva del Castillo (pp. 349–365). Santander: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

Cáceres, I., Rosell, J., & Huguet, R. (1998). Séquence d’utilisation de la biomasse animale dans le gisement de l’Abric Romani. Quaternaire, 9, 379–383.

Callapez, P. (2000). Upper Pleistocene marine invertebrates from Gruta da Figueira Brava. In M. Telles Antunes (Ed.), O Ultimos Neandertais em Portugal (pp. 84–101). Lisbon: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa.

Carrión, J. S., Finlayson, C., Fernández, S., Finlayson, C., Allué, E., López-Sáez, J., et al. (2008). A coastal reservoir of biodiversity for Upper Pleistocene human populations: Palaeoecological investigations in Gorham’s Cave (Gibraltar) in the context of the Iberian Peninsula. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27, 2118–2135.

Castaños, P. (2005). Revisión actualizada de las faunas de macromamíferos del Würm antiguo en la región cantábrica. In R. Montes & J. A. Lasheras (Eds.), Neanderthales Cantábricos, Estado de la Cuestión (pp. 201–207). Santander: Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, Monografías 20.

Cortés, M. (2007a). El Paleolítico Medio y Superior en el Sector Central de Andalucía. Madrid: Monografias del Museo de Altamira 22.

Cortés, M. (2007b). Cueva Bajondillo (Torremolinos). Málaga: Diputación de Málaga.

Cortés, M, Simón, M., Fernández, E., Gutierrez, C., Lozano-Francisco, M., Morales, A., et al. (2005). Algunos datos sobre el Paleolítico Superior de la Cueva de Nerja. In J. L. Sanchidrián, A. M. Márquez, & J. M. Fullola (Eds.), La Cuenca Mediterránea durante el Paleolítico Superior (pp. 298–315). Málaga: Fundación Cueva de Nerja.

Cortés, M., Morales, A., Simón, M., Bergadà, M., Delgado, A., López, P., et al. (2008). Palaeoenvironmental and cultural dynamics of the coast of Málaga (Andalusia, Spain) during the Upper Pleistocene and early Holocene. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27, 2176–2193.

Dari, A. (1999). Les grands mammifères du site Pleistocène supérieur de la grotte du Castillo. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie I, Prehistoria y Arqueología, 12, 103–107.

Dari, A., & Renault-Miskovsky, J. (2001). Etudes paléoenvironnementales dans la grotte “El Castillo”. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie I, Prehistoria y Arqueología, 14, 121–144.

Davidson, I. (1989). La Economía del Final del Paleolítico en la España Oriental. Valencia: Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica, Trabajos Varios 85.

Davis, S. (2002). The mammals and birds from the Gruta do Caldeirão, Portugal. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, 5, 29–98.

d’Errico, F., & Sanchez-Goñi, M. F. (2003). Neanderthal extinction and the millennial scale climatic variability of OIS 3. Quaternary Science Reviews, 22, 769–788.

Estevez, J. (1987). La fauna de l’Arbreda (sector Alfa) en el conjunt de faunes del Plistocè Superior. Cypsela, 6, 73–87.

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., & Andrews, P. (2000). The taphonomy of Pleistocene caves, with particular reference to Gibraltar. In C. Stringer, R. N. E. Barton, & J. C. Finlayson (Eds.), Neanderthals on the edge (pp. 171–182). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Fernández-Laso, M. C., Rivales, F., & Rosell, J. (2010). Intra-site changes in seasonality and their consequences on the faunal assemblages from Abric Romani. Quaternaire, 21, 255–263.

Finlayson, C., Giles, F., Rodríguez-Vidal, J., Fa, D., Gutierrez, J., Santiago, A., et al. (2006). Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe. Nature 443, 850–853 (with supplementary on-line information).

Freeman, L. G. (1973). The significance of mammalian faunas from Paleolithic occupations in Cantabrian Spain. American Antiquity, 38, 3–44.

Freeman, L. G. (1981). The fat of the land: Notes on Paleolithic diet in Iberia. In R. S. O. Harding & G. Teleki (Eds.), Omnivorous primates (pp. 104–165). New York: Columbia University Press.

Garrod, D., Buxton, L., Smith, G. E., & Bate, D. (1928). Excavation of a Mousterian rock-shelter at Devil’s Tower, Gibraltar. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 58, 33–113.

González-Sampériz, P., Leroy, S., Carrión, J., Fernández, S., García-Antón, M., Uzquiano, P., et al. (2010). Steppes, savannahs, forests and phytodiversity reservoirs during the Pleistocene in the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of Palaeobotany & Palynology. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2010.03.009.

Grayson, D., & Delpech, F. (2002). Specialized Early Upper Palaeolithic hunters in Southwestern France? Journal of Archaeological Science, 29, 1439–1449.

Grayson, D., & Delpech, F. (2003). Ungulates and the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition at Grotte XVI (Dordogne, France). Journal of Archaeological Science, 30, 1633–1648.

Grayson, D., & Delpech, F. (2006). Was there increasing dietary specialization across the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition in France? In N. Conard (Ed.), When Neanderthals and Modern Humans Met (pp. 377–417). Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.

Grayson, D., & Delpech, F. (2008). The large mammals of Roc de Combe (Lot, France): The Châtelperronian and Aurignacian assemblages. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 27, 338–362.

Green, R. et al. (2010). A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328: 710–725.

Hilderbrand, G., Farley, S., Robbins, C., Hanley, T., Titus, K., & Servheen, C. (1996). Use of stable isotopes to determine diets of living and extinct bears. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 74, 2080–2088.

Hockett, B., & Bicho, N. (2000). The rabbits of Picareiro Cave: Small mammal hunting during the late Upper Palaeolithic in the Portuguese Estremadura. Journal of Archaeological Science, 27, 715–723.

Hockett, B., & Haws, J. (2002). Taphonomic and methodological perspectives of leporid hunting during the Upper Paleolithic of the Western Mediterranean Basin. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 9, 269–302.

Hockett, B., & Haws, J. (2005). Nutritional ecology and the human demography of Neanderthal extinction. Quaternary International, 137, 21–34.

Hockett, B., & Haws, J. (2009). Continuity in animal resource diversity in Late Pleistocene human diet of Central Portugal. Before Farming 2009/2.2, 1–13.

Iturbe, G., Fumanal, M. P., Carrión, J. S., Cortell, E., Martínez, R., Guillem, P., et al. (1993). Cova Beneito: una perspectiva interdisciplinar. Recerques del Museu d’Alcoi, 2, 23–88.

Jennings, R., Giles, F., Barton, R., Collcutt, S., Gale, R., Gleed-Owen, C., et al. (2009). Quaternary Science Reviews. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.11.014.

Jones, E.L. (2012). Upper Paleolithic rabbit exploitation and landscape patchiness: the Dordogne vs. Mediterranean Spain. Quaternary International 265, 52–60.

Klein, R., & Cruz-Uribe, K. (1994). The Paleolithic mammalian fauna from the 1910-14 excavations at El Castillo Cave. In J. A. Lasheras (Ed.), Homenaje al Dr. Joaquín González Echegaray (pp. 141–158). Madrid: Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, Monografías 17.

Klein, R., & Steele, T. (2008). Gibraltar data are too sparse to inform on Neanderthal exploitation of coastal resources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, E115.

Landry, G., & Burke, A. (2007). El Castillo: The Obermaier faunal collection. In J. M. Maillo & E. Baquedano (Eds.) Miscelánea en Homenaje a Victoria Cabrera (Vol. I, pp. 104–112). Alcalá: Zona Arqueológica 7.

Lindly, J. (1988). Hominid carnivore activity at Middle and Upper Paleolithic cave sites in eastern Spain. Munibe, 40, 45–70.

Manne, T., & Bicho, F. (2009). Val Boi: Rendering new understandings of resource intensification & diversification in southwestern Iberia. Before Farming 2009/2.1, 1–21.

Manne, T., & Bicho, N. (2011). Prying new meaning from limpet harvesting at Vale Boi during the Upper Paleolithic. In N. Bicho, J. Haws, & L. Davis (Eds.), Trekking the Shore (pp. 273–289). New York: Springer.

Marín-Arroyo A. B. (2009a). The human use of the montane zone of Cantabrian Spain during the Lalte Glacial: Faunal evidence from El Mirón Cave. Journal of Anthropological Research, 65, 69–102.

Marín-Arroyo A. B. (2009b). Economic adaptations during the Late Glacial in northern Spain. A simulation approach. Before Farming 2009/2.3, 1–18.

Marín-Arroyo A. B. (2010). La fauna de Mamíferos en el Cantábrico Oriental durante el Magdaleniense y Aziliense. Santander: Ediciones de la Universidad de Cantabria.

Maroto, J, Soler, N., & Fullola, J. M. (1996). Cultural change between Middle and Upper Palaeolithic in Catalonia. In E. Carbonell & M. Vaquero (Eds.), The last Neanderthals, The first antatomically modern humans (pp. 219–250). Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

Martín Penela, A. (1986). Los grandes mamíferos del yacimiento pleistoceno superiorde Cueva Hora (Darro, Granada, España). Antropología y Paleoecología Humana, 4, 107–128.

Martínez-Moreno, J. (2005). Una aproximación zooarqueológica al estudio de los patrones de subsistencia del Paleolítico Medio Cantábrico. In R. Montes & J. A. Lasheras (Eds.), Neanderthales Cantábricos, Estado de la Cuestión (pp. 209–230). Santander: Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, Monografías 20.

Pacher, M., & Stuart, A. J. (2008). Extinction chronology and palaeobiology of the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus). Boreas. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2008.00071.x.

Pérez Ripoll, M. (2001). Marcas antrópicas en los huesos de conejo. In V. Villaverde (Ed.), De Neanderthales a Cromañones: El Inicio del Poblamiento Humano en las Tierras Valencianas (pp. 119–124). Valencia: Universitat de Valencia.

Pérez Ripoll, M. (2006). Caracterización de las fracturas antrópicas y sus tipologías en huesos de conejo procedentes de los niveles gravetienses de la Cova de les Cendres. Munibe, 57(1), 239–254.

Pérez Ripoll, M., & Martínez R. (2001). La caza, el aprovechamiento de las presas y el comportamiento de las comunidades cazadores prehistóricas. In V. Villaverde (Ed.), De Neanderthales a Cromañones: El Inicio del Poblamiento Humano en las Tierras Valencianas (pp. 73–98). Valencia: Universitat de Valencia.

Quesada, J. M. (2006). Faunas del Auriñaciense y Gravetiense cantábrico. In J. Maillo & E. Baquedano (Eds.), Miscelánea en Homenaje a Victoria Cabrera (Vol. 1, pp. 406–421). Alcalá: Zona Arqueológica 7.

Rodríguez, J., Giles, F., & Riquelme, J. (2010). El registro fósil de hienas en las cuevas de Gorham’s y Vanguard (Gibraltar): contexto paleogeográfico. Zona Arqueológica, 13, 354–364.

Rosell, J., et al. (2010). A stop along the way: The role of Neanderthal groups at Level III of Teixoneres Cave (Moià, Barcelona, Spain). Quaternaire, 21, 239–253.

Rosell, J., Blasco, R., Huguet, R., Caceres, I., Saladie, P., Rivals, F., et al. (2012). Occupational patterns and subsistence strategies in Level J of Abric Romani. In E. Carbonell (Ed.), High resolution archaeology and Neanderthal behavior: Time and space in Level J of Abric Romaní (Capellades, Spain) (pp. 313–372). New York: Springer.

Speth, J., & Spielmann, K. (1983). Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2, 1–31.

Stiner, M. (1994). Honor among thieves: A zooarchaeological study of Neanderthal ecology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stiner, M. (2001). Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and Paleolithic demography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 6993–6996.

Stiner, M. (2003). Zooarchaeological evidence for resource intensification in Algarve, Southern Portugal. Promontoria, 1, 27–61.

Stiner, M., Munro, N., Surovell, T., Tchernov, E., & Bar-Yosef, O. (1999). Paleolithic population growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science, 283, 190–194.

Straus, L. G. (1977). Of deerslayers and mountain men: Paleolithic faunal exploitation in Cantabrian Spain. In L. R. Binford (Ed.), For theory building in archaeology (pp. 41–76). New York: Academic Press.

Straus, L. G. (1982). Carnivores and cave sites in Cantabrian Spain. Journal of Anthropological Research, 38, 75–96.

Straus, L. G., & Clark, G. A. (1986). La Riera Cave. Tempe: Anthropological Research Papers 36.

Straus, L. G. (1992). Iberia before the Iberians. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Straus, L. G. (1993). Upper Paleolithic hunting tactics and weapons in Western Europe. In. G. L. Peterkin, H. Bricker, & P. Mellars (Eds.), Hunting and animal exploitation in the Later Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Eurasia (pp. 83–93). Washington: Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 4.

Stringer, C., Finlayson, J. C., et al. (2008). Neanderthal exploitation of marine mammals in Gibraltar. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 14319–14324.

Stuart, A. J., & Lister, A. (2007). Patterns of Late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions in Europe and northern Asia. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, 259, 287–297.

Villaverde, V., Martínez-Valle, R., Guillem, P., & Fumanal, M. P. (1996). Mobility and the role of small game in the Middle Paleolithic of the central region of the Spanish Mediterranean: A comparison of Cova Negra with other Paleolithic deposits. In E. Carbonell & M. Vaquero (Eds.), The last Neanderthals the first anatomically modern humans (pp. 267–288). Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

Yravedra, J. (2002). Subsistencia en la transición del Paleolítico Medio al Paleolítico Superior de la Peninsula Ibérica. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 59, 9–28.

Yravedra, J. (2006). Acumulaciones biológicas en yacimientos arqueológicos: Amalda VII y Esquilleu III-IV. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 63, 55–78.

Yravedra, J. (2007). Nuevas contribuciones en el comportamiento cinegético de la Cueva de Amalda. Munibe, 58, 43–88.

Zilhão, J., & Trinkaus, E. (2002). Portrait of the Artist as a Child: The Gravettian Human Skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho and its Archaeological Context. Lisbon: Trabalhos de Arqueologia 22.

Acknowledgments